Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Progress on OWT Foundations and Wave Energy Devices

2.1. Research Progress on OWT Foundations

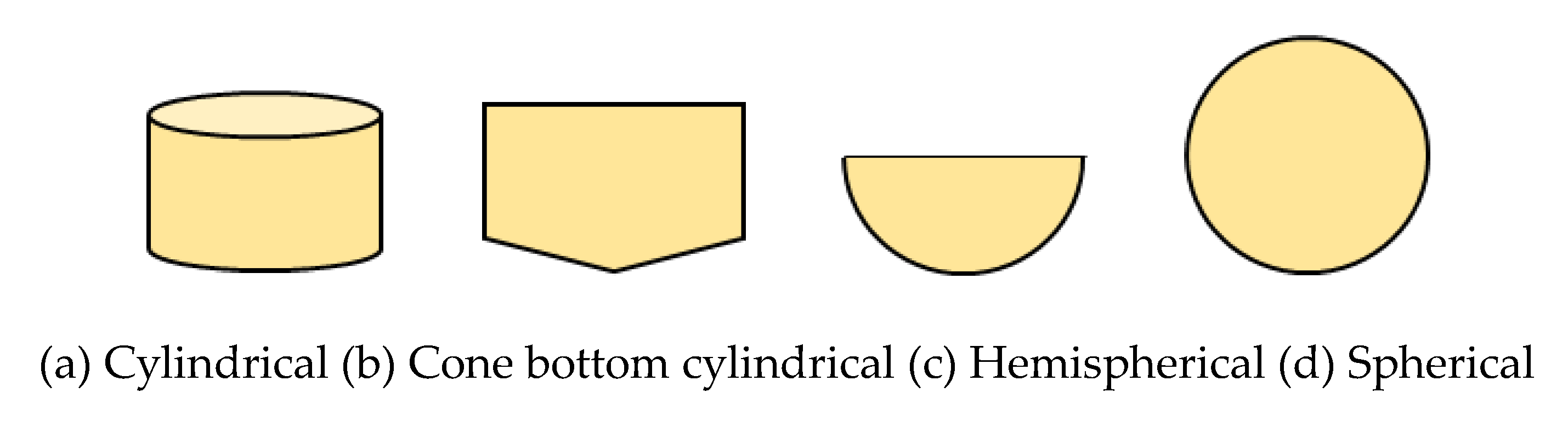

2.2. Research Progress on WECs

- Development from single devices to arrays and integrated systems, especially in hybrid wind–wave power generation systems, where interactions between devices introduce new effects on energy capture and platform stability, becoming an important research topic in recent years.

3. Research Progress of Hybrid Wind–Wave Power Generation Systems

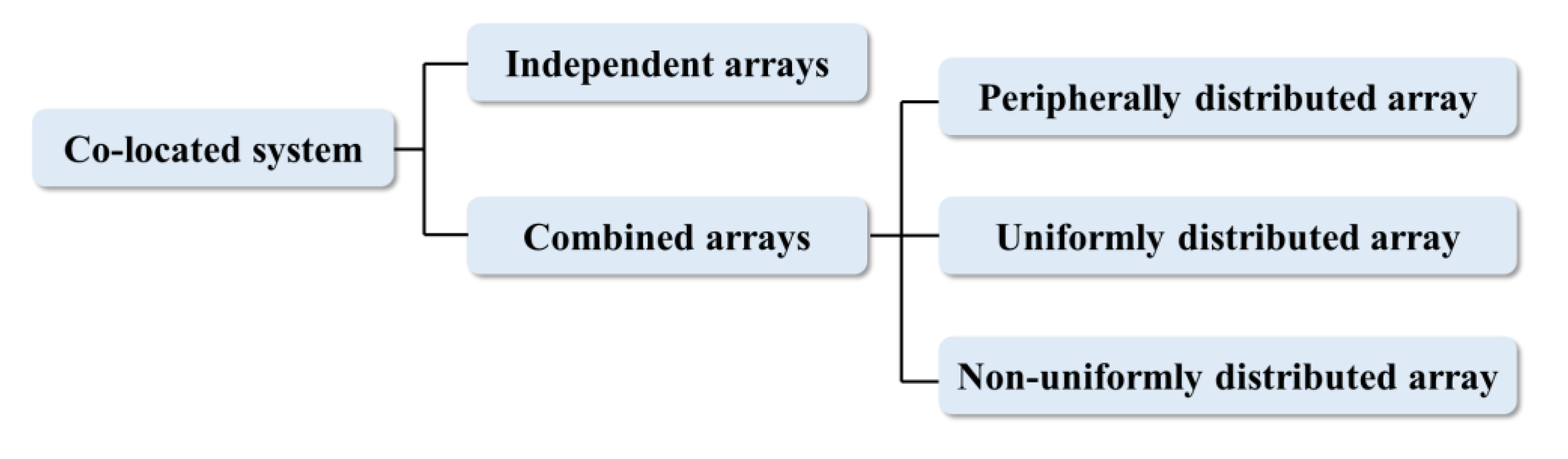

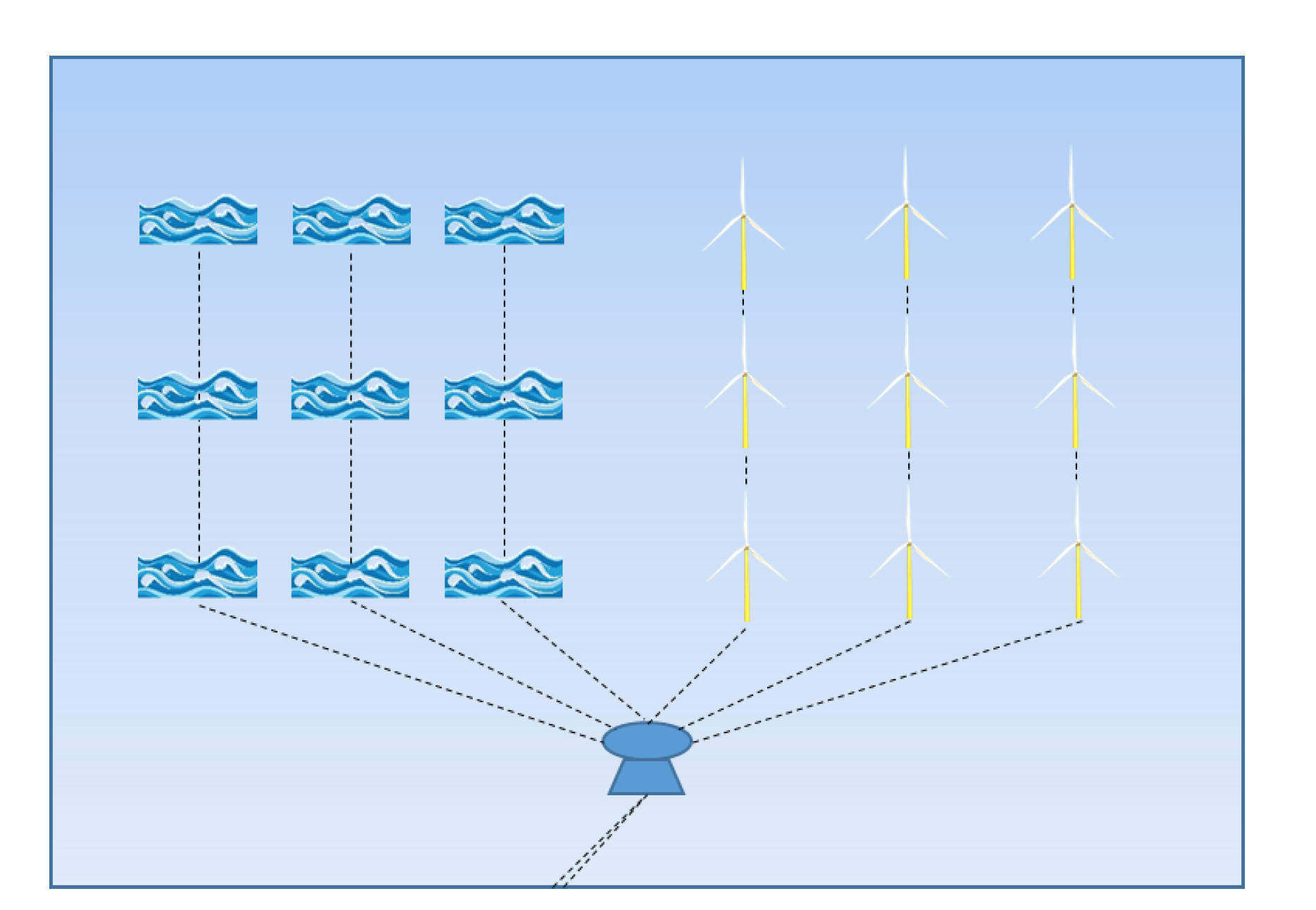

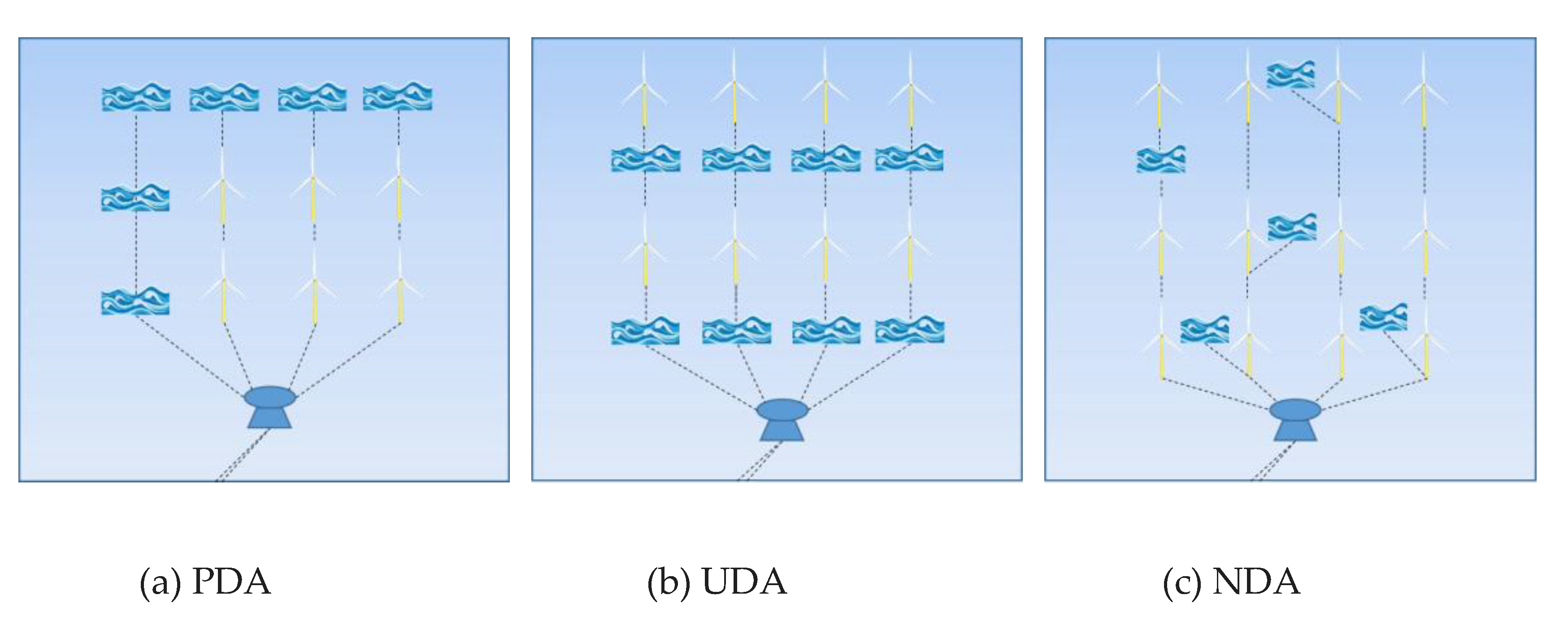

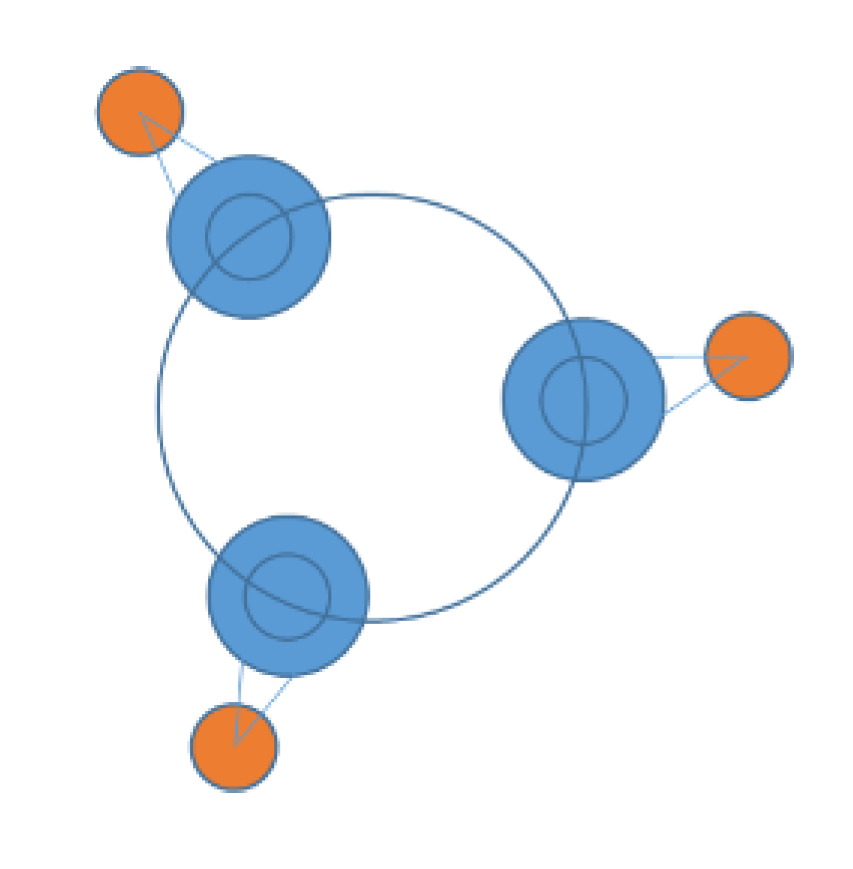

3.1. Co-Located Systems

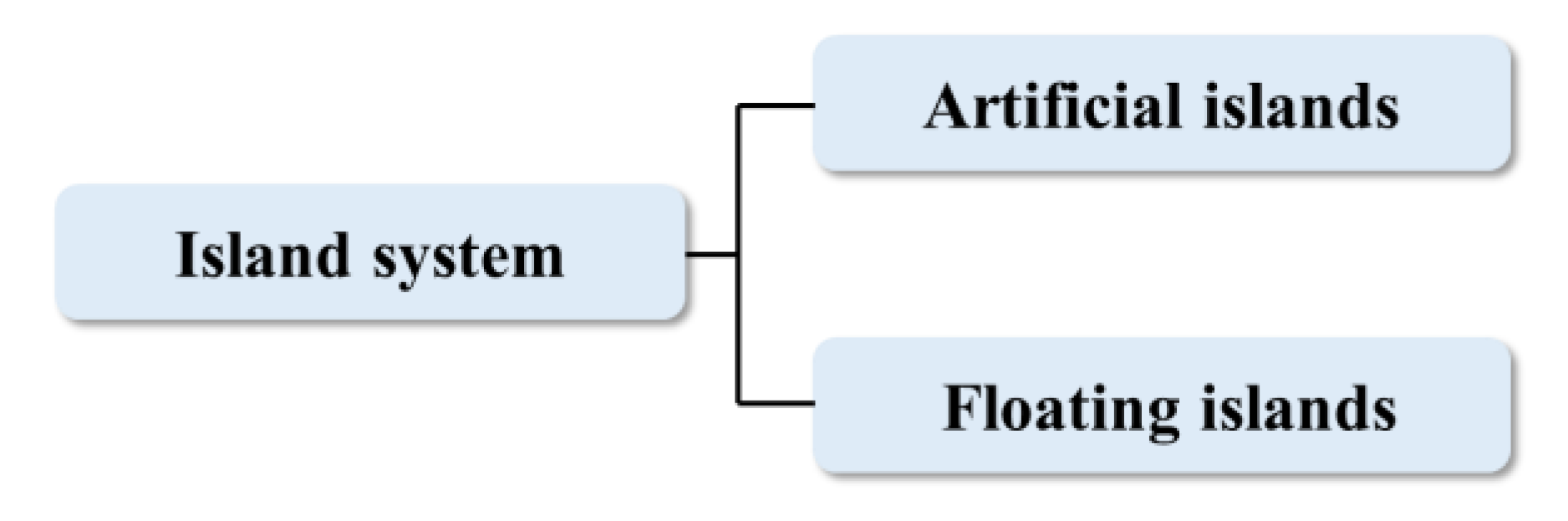

3.2. Island Systems

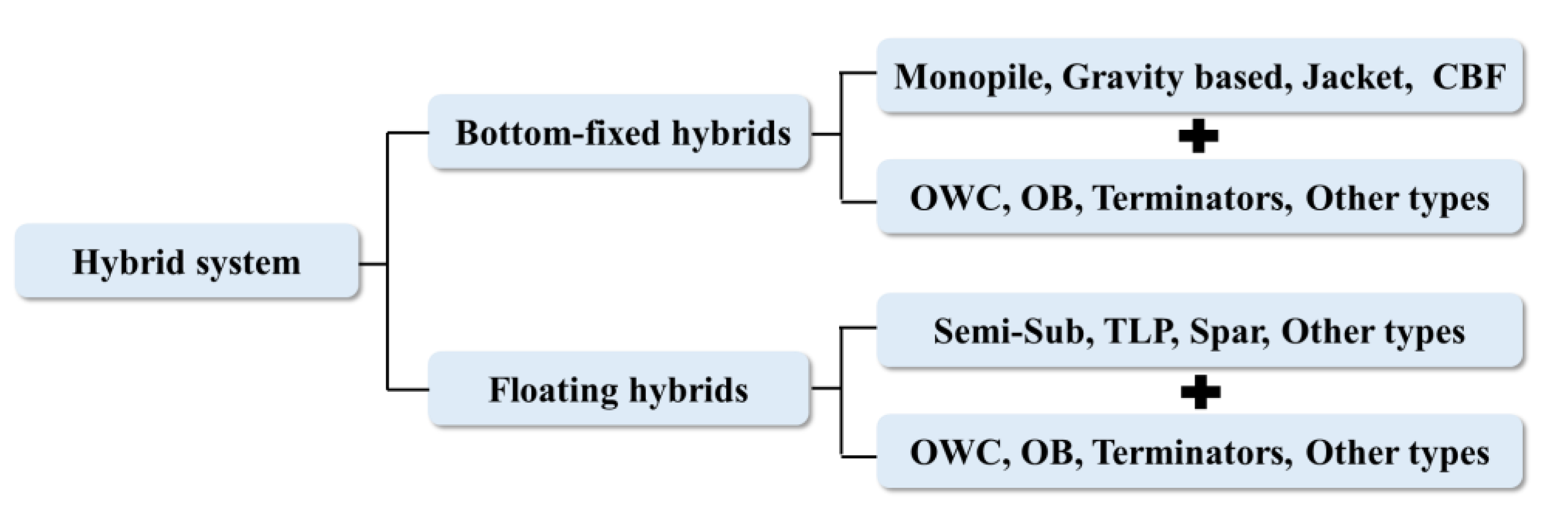

3.3. Hybrid Systems

3.3.1. Bottom-Fixed Hybrid Systems

3.3.2. Floating Hybrid Systems

4. Optimization of Hybrid Wind–Wave Energy Systems: Technologies and Layouts

4.1. Technological Optimization

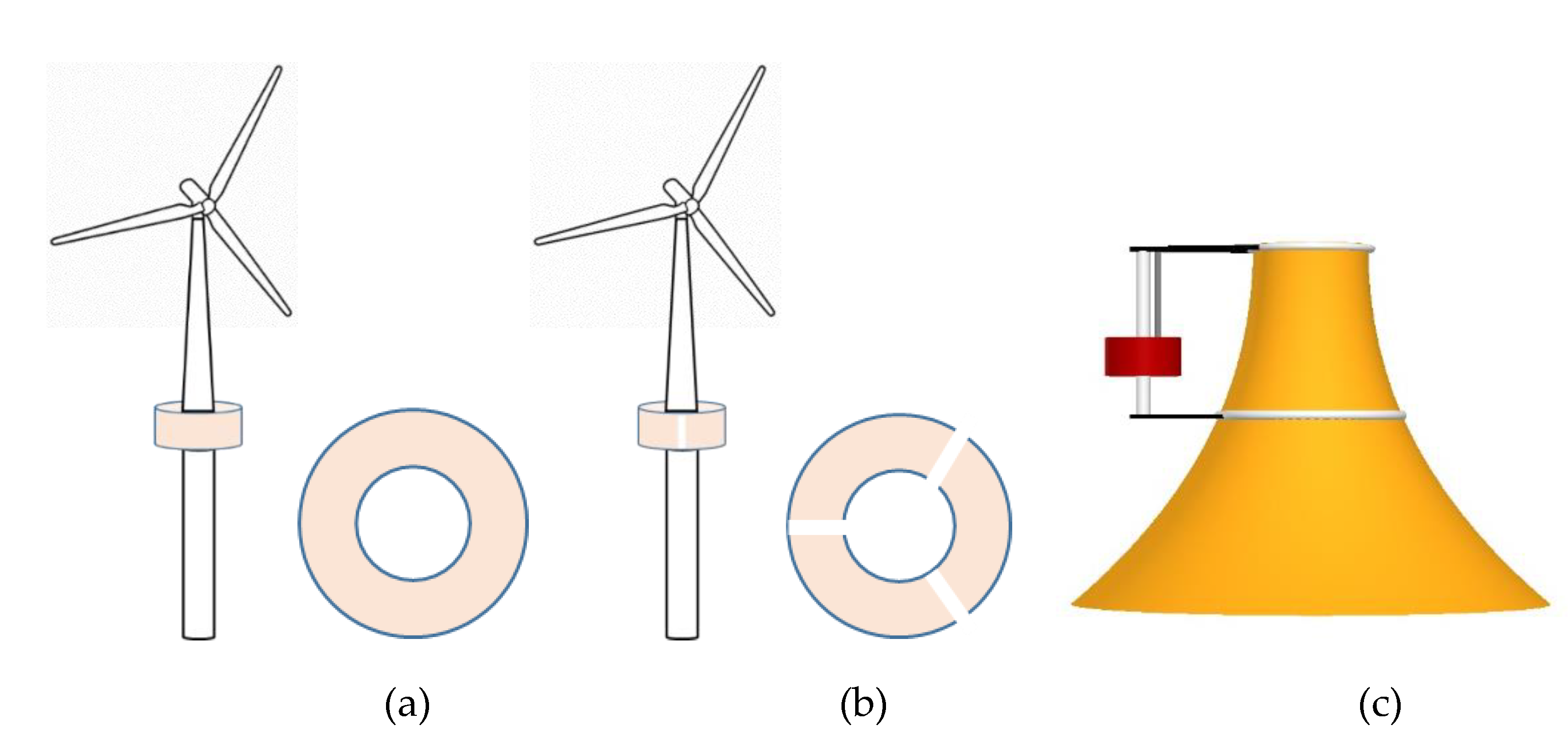

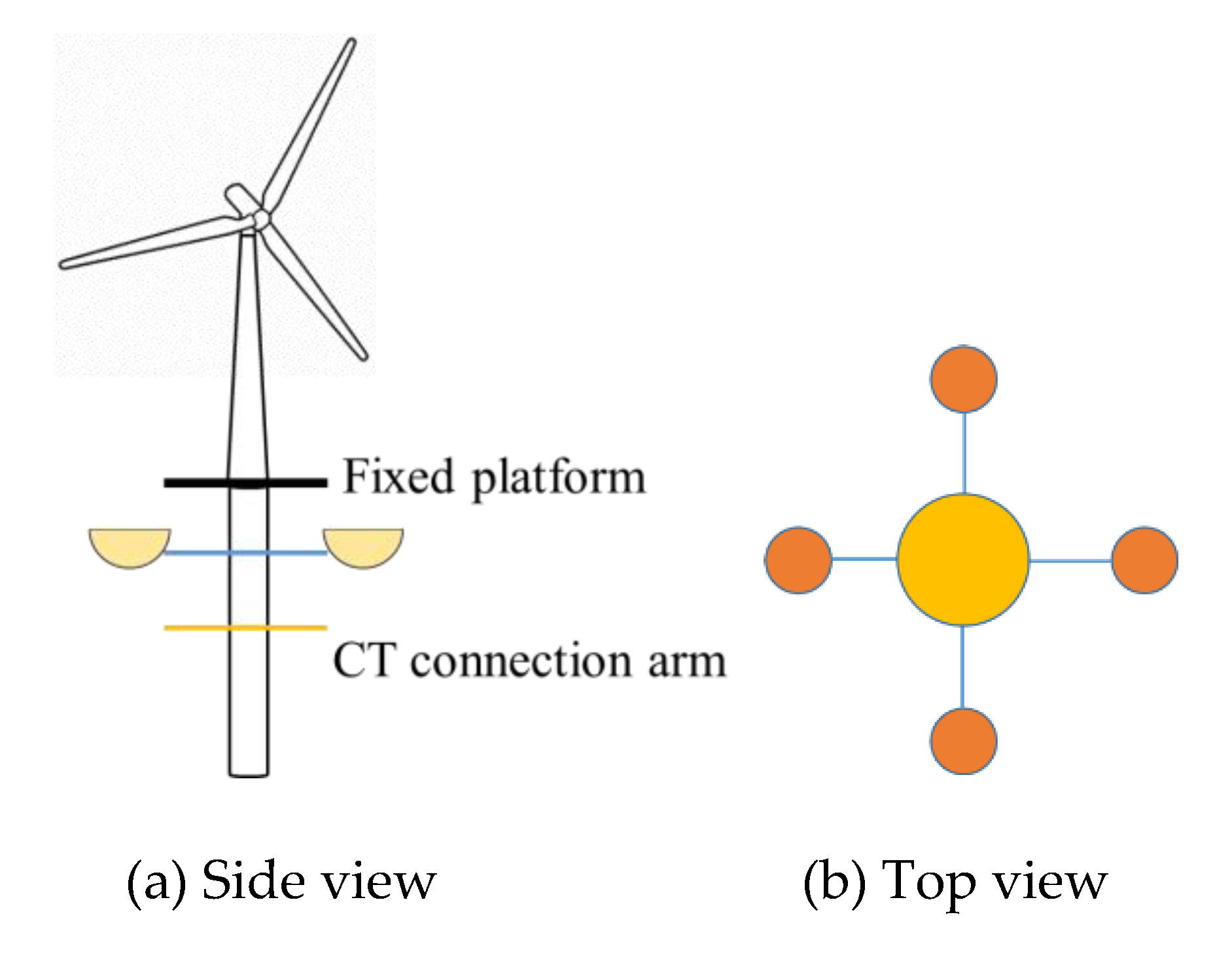

4.1.1. Integrated Design of Foundations and WECs

4.1.2. Power Conversion and Performance Enhancement

4.1.3. Innovative Designs of Hybrid Foundation Concepts

4.2. Layout Optimization

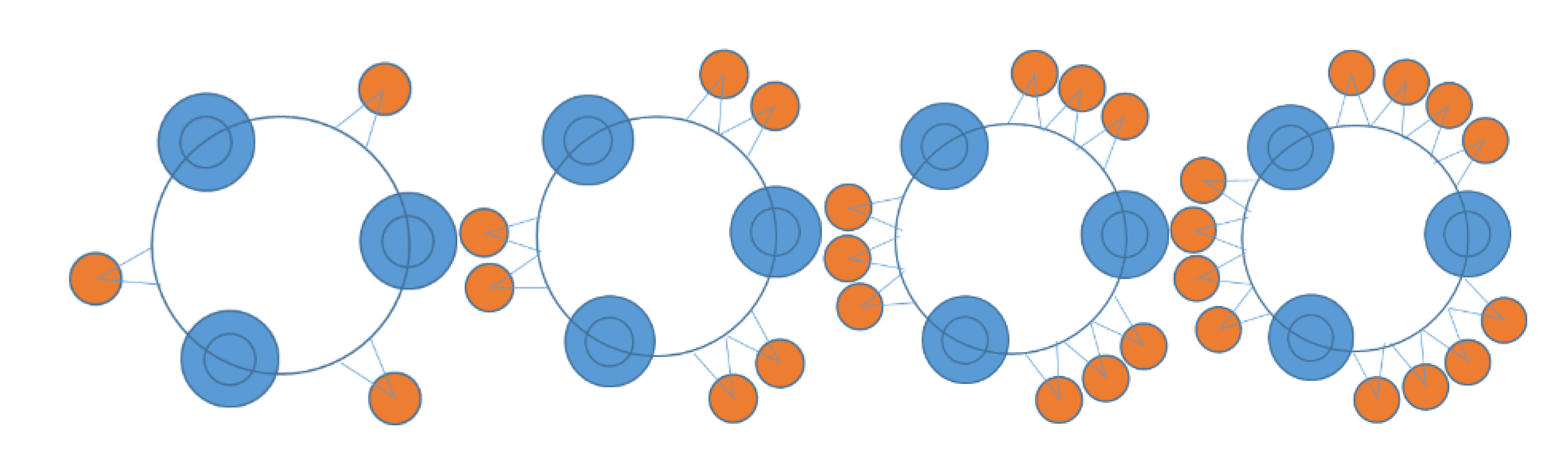

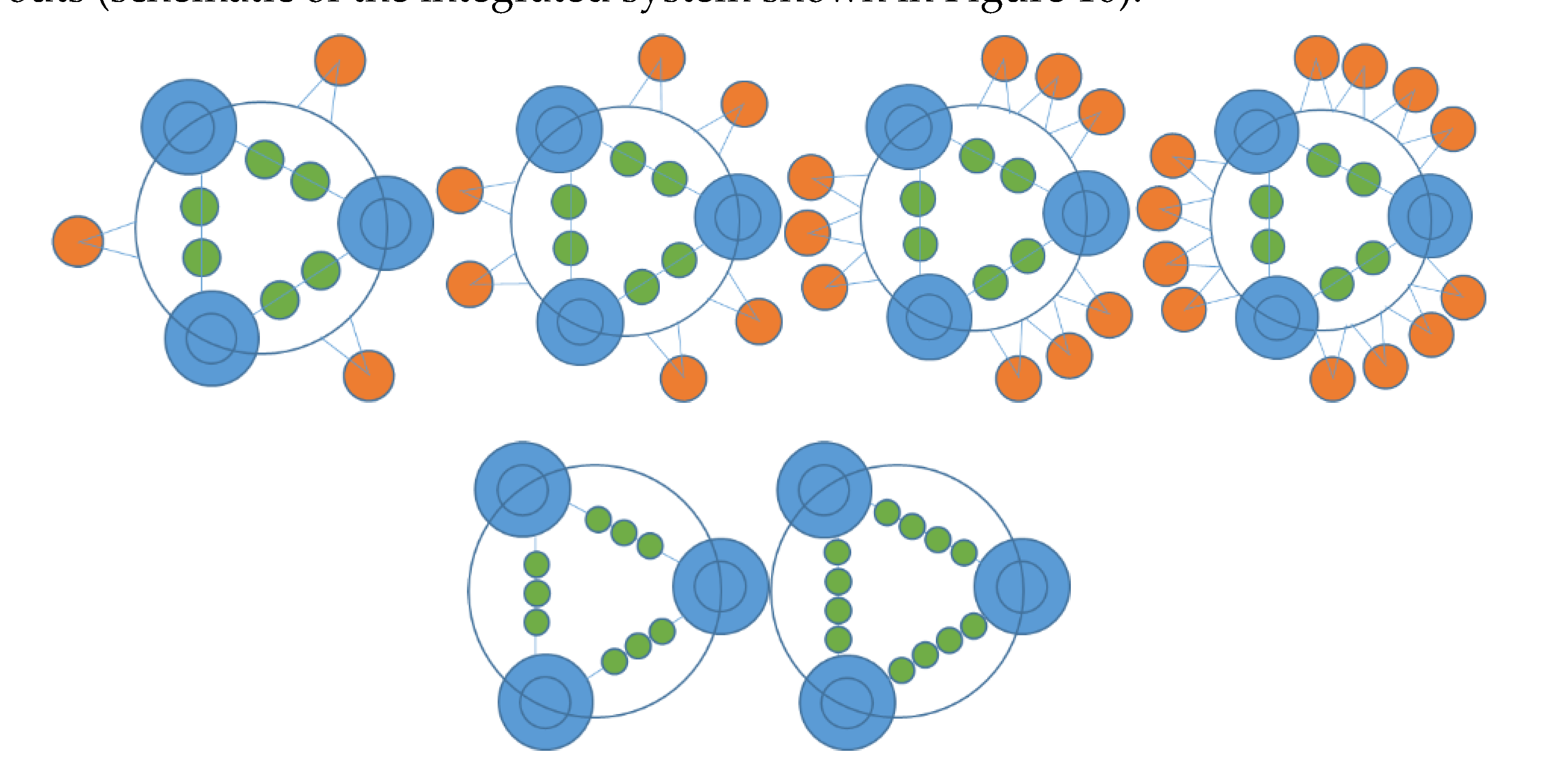

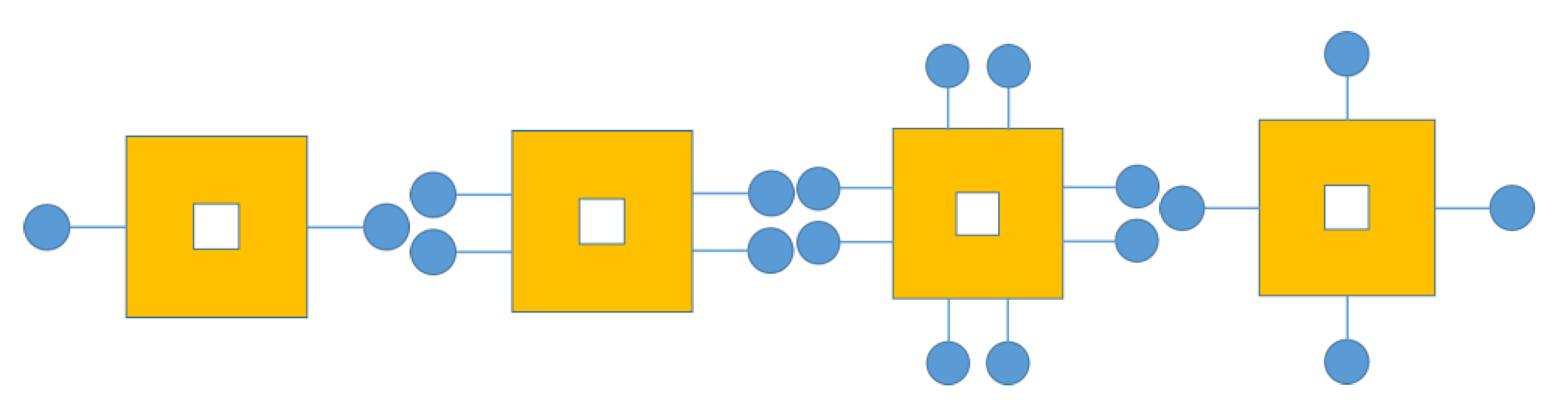

4.2.1. Key Layout Parameters of Hybrid Wind–Wave Arrays

4.2.2. Layout Optimization Algorithms and Simulation Tools

4.2.3. Platform Type Adaptation Layout Strategy

5. Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Research

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Future Research

Data Availability

Declaration of competing interest

| Nomenclature | UN-SDG | United Nations Sustainable Development Goal | |

| Abbreviation | TLP | tension-leg platform | |

| WWHS | Wind–wave hybrid system | OWC | oscillating water column |

| OWT | Offshore wind turbine | PDA | peripherally distributed array |

| FOWT | Floating offshore wind turbine | UDA | uniformly distributed array |

| CBF | Composite bucket foundation | NDA | non-uniformly distributed array |

| OB | Oscillating buoy | OSPREY | Ocean Surge-driven Renewable Energy |

| PTO | Power take-off | OWCD | oscillating water column device |

| WEC | Wave energy converter | BEM | boundary element method |

| RAO | Response amplitude operator | HOREHS | hybrid offshore renewable energy harvesting system |

| NMSC | The National Marine Science Data Center |

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Kong, D. The Real Effect of Legal Institutions: Environmental Courts and Firm Environmental Protection Expenditure. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2019, 98, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F.; van den Berg, M. Illustrating the Use of Concepts from the Discipline of Policy Studies in Energy Research: An Explorative Literature Review. Energy Research & Social Science 2016, 21, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.; Kamran, M.S.; Hai, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ali, A. Knowledge Structuring for Enhancing Mechanical Energy Harvesting (MEH): An in-Depth Review from 2000 to 2020 Using CiteSpace. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 150, 111460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagai, K.; Takarada, T.; Funatsu, M.; Nezu, K. Development of Low-CO2-Emission Vehicles and Utilization of Local Renewable Energy for the Vitalization of Rural Areas in Japan. IATSS Research 2014, 37, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Ranking of Factors Affecting Environmental Pollution. International journal of industrial engineering and operational research 2023, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekut, M. The Consumption of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) by the European Union Households between 2004 and 2019. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.; Liu, G.; Fan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ali, A.; Li, H.; Azam, A.; Cao, H.; Mohamed, A.A. Energy Regenerative Shock Absorber Based on a Slotted Link Conversion Mechanism for Application in the Electrical Bus to Power the Low Wattages Devices. Applied Energy 2023, 347, 121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, S.; Vardhan, S.; Patnaik, A. Sustainability of Maintenance Management Practices in Hydropower Plant: A Conceptual Framework. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 28, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.-F.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Banja, M.; Motola, V. Renewable Energy Policy Framework and Bioenergy Contribution in the European Union – an Overview from National Renewable Energy Action Plans and Progress Reports. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 51, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.-G. of the E. Commission. Report from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions: EU citizenship report 2020: empowering citizens and protecting their rights. 2020.

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Ma, R. Assessing the National Synergy Potential of Onshore and Offshore Renewable Energy from the Perspective of Resources Dynamic and Complementarity. Energy 2023, 279, 128106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tomasgard, A.; Knudsen, B.R.; Svendsen, H.G.; Bakker, S.J.; Grossmann, I.E. Modelling and Analysis of Offshore Energy Hubs. Energy 2022, 261, 125219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldsund, M.; Reyes-Lúa, A.; Fu, C.; Ditaranto, M.; Nekså, P.; Mazzetti, M.J.; Brekke, O.; Bindingsbø, A.U.; Grainger, D.; Pettersen, J. Low Carbon Power Generation for Offshore Oil and Gas Production. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2023, 17, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richts, C.; Jansen, M.; Siefert, M. Determining the Economic Value of Offshore Wind Power Plants in the Changing Energy System. Energy Procedia 2015, 80, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, T.; Joanis, M.; Abdoli, S. Power Generation Mix and Electricity Price. Renewable Energy 2024, 221, 119761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Fu, L.; Dai, S.; Collu, M.; Cui, L.; Yuan, Z.; Incecik, A. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of a Hybrid WEC-Breakwater System Combining an Oscillating Water Column and an Oscillating Buoy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 169, 112909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Kamranzad, B.; Lin, P. Joint Exploitation Potential of Offshore Wind and Wave Energy along the South and Southeast Coasts of China. Energy 2022, 249, 123710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Bashir, M.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; Li, S. Fully Coupled Dynamic Responses of Barge-Type Integrated Floating Wind-Wave Energy Systems with Different WEC Layouts. Ocean Engineering 2024, 313, 119453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P Patel, R.; Nagababu, G.; Kachhwaha, S.S.; V V Arun Kumar, S.; M, S. Combined Wind and Wave Resource Assessment and Energy Extraction along the Indian Coast. Renewable Energy 2022, 195, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P.; Wang, C.M.; Tay, Z.Y.; Luong, V.H. Wave Energy Converter and Large Floating Platform Integration: A Review. Ocean Engineering 2020, 213, 107768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T.; Lugni, C. Experimental and Numerical Comparisons of Hydrodynamic Responses for a Combined Wind and Wave Energy Converter Concept under Operational Conditions. Renewable Energy 2016, 93, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astariz, S.; Abanades, J.; Perez-Collazo, C.; Iglesias, G. Improving Wind Farm Accessibility for Operation & Maintenance through a Co-Located Wave Farm: Influence of Layout and Wave Climate. Energy Conversion and Management 2015, 95, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeri, C.; Galanis, G.; Spyrou, C.; Diamantis, D.; Baladima, F.; Koukoula, M.; Kallos, G. Assessing the European Offshore Wind and Wave Energy Resource for Combined Exploitation. Renewable Energy 2017, 101, 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astariz, S.; Iglesias, G. Output Power Smoothing and Reduced Downtime Period by Combined Wind and Wave Energy Farms. Energy 2016, 97, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , Yan, S., Shi, H., Ma, Q., Dong, X., Cao, F. Wave Load Characteristics on a Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy System. Ocean Engineering 2024, 294, 116827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, H.R. , Ghassemi, H.; He, G. Numerical Study of the Wavestar Wave Energy Converter with Multi-Point-Absorber around DeepCwind Semisubmersible Floating Platform. Ocean Engineering 2021, 232, 109177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lim, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, S.-W. A Comprehensive Review of Foundation Designs for Fixed Offshore Wind Turbines. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2025, 17, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-Y.; Nam, W.; Ryu, M.S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Epureanu, B.I. A Review of Foundations of Offshore Wind Energy Convertors: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 88, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qi, X.; Le, C.; Ding, H. Bearing Capacity and Load Transfer of Brace Topological in Offshore Wind Turbine Jacket Structure. Ocean Engineering 2020, 199, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.-T.; Lee, D. Development of Jacket Substructure Systems Supporting 3MW Offshore Wind Turbine for Deep Water Sites in South Korea. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2022, 14, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathern, A.; Haar, C. von der; Marx, S. Concrete Support Structures for Offshore Wind Turbines: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Trends. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Le, C. Integrated Towing Transportation Technique for Offshore Wind Turbine with Composite Bucket Foundation. China Ocean Eng 2022, 36, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Le, C.; Ding, H. Seismic Responses of Two Bucket Foundations for Offshore Wind Turbines Based on Shaking Table Tests. Renewable Energy 2022, 187, 1100–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Song, H.; Bian, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, X. Theoretical Analysis of Wave Run-up on the Composite Bucket Foundation under Wave Action. Ocean Engineering 2024, 308, 118347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Research Status and Prospects of In-Situ Installation Technology for Floating Offshore Wind Turbine. Ocean Engineering 2026, 343, 123253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bachynski-Polić, E.E. Analysis of Difference-Frequency Wave Loads and Quadratic Transfer Functions on a Restrained Semi-Submersible Floating Wind Turbine. Ocean Engineering 2021, 232, 109165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y.; Shao, Y.; Mao, W.; Han, Z.; Huang, C.; Gu, X.; Jiang, Z. Transient Response of a TLP-Type Floating Offshore Wind Turbine under Tendon Failure Conditions. Ocean Engineering 2021, 220, 108486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wen, B.; Chen, G.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Peng, Z.; Tian, X. Feasibility Studies of a Novel Spar-Type Floating Wind Turbine for Moderate Water Depths: Hydrodynamic Perspective with Model Test. Ocean Engineering 2021, 233, 109070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.C.; Holcombe, A.; Brown, S.; Ransley, E.; Hann, M.; Greaves, D. Evolution of Floating Offshore Wind Platforms: A Review of at-Sea Devices. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 183, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Stiesdal. Hywind: the world’s first floating MW-scale wind turbine. Wind directions (Dec. 2009.

- Principle Power. https://www.principlepowerinc.com/. Accessed in 2023.

- Wan, L.; Moan, T.; Gao, Z.; Shi, W. A Review on the Technical Development of Combined Wind and Wave Energy Conversion Systems. Energy 2024, 294, 130885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmani, A.; Nikoo, M.R.; Gandomi, A.H.; Chen, M.; Nazari, R. Advancements in Optimizing Wave Energy Converter Geometry Utilizing Metaheuristic Algorithms. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 197, 114398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zheng, S.; Greaves, D. On the Scalability of Wave Energy Converters. Ocean Engineering 2022, 243, 110212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ning, D. A Review of Numerical Methods for Studying Hydrodynamic Performance of Oscillating Water Column (OWC) Devices. Renewable Energy 2024, 233, 121177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemipour, N.; Izanlou, P.; Jahangir, M.H. Feasibility Study on Utilizing Oscillating Wave Surge Converters (OWSCs) in Nearshore Regions, Case Study: Along the Southeastern Coast of Iran in Oman Sea. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 367, 133090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, S.; Aggidis, G.A. Development of Multi-Oscillating Water Columns as Wave Energy Converters. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 107, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodoo, A.; Imai, Y. Experimental Investigation of a Novel Adjustable-Slope Onshore Overtopping Wave Energy Converter for Coastal Protection and Energy Generation. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2025, 28, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, H.; Cui, Y.; Kim, K. Experimental Study on Overtopping Performance of a Circular Ramp Wave Energy Converter. Renewable Energy 2017, 104, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, M.M.; Martins, J.C.; Gomes, A.P.; Puhl, E.; Rocha, L.A.O.; Isoldi, L.A.; Gomes, M. das N.; dos Santos, E.D. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of the Geometry of a Laboratory-Scale Overtopping Wave Energy Converter Using Constructal Design. Renewable Energy 2024, 236, 121497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.-H. A Synthesis of Numerical Methods for Modeling Wave Energy Converter-Point Absorbers. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4352–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.; Yi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Aslam, T.; Mugheri, S.A.; Abdelrahman, M.; Ali, A.; Qi, L. Wave Energy Evolution: Knowledge Structure, Advancements, Challenges and Future Opportunities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 205, 114880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Iglesias, G. Concept and Performance of a Novel Wave Energy Converter: Variable Aperture Point-Absorber (VAPA). Renewable Energy 2020, 153, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, D.; Rathnakumar, P.; Marichamy, S.; Ganesan, P.; Vinothbabu, K.; Stalin, B. A Technological Assessment of the Ocean Wave Energy Converters. In Proceedings of the Advances in Industrial Automation and Smart Manufacturing; Arockiarajan, A., Duraiselvam, M., Raju, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1057–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Göteman, M. Wave Energy Parks with Point-Absorbers of Different Dimensions. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2017, 74, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, A.; Fiévez, J. Numerical Prediction of Extreme Loads on the CETO Wave Energy Converter; 2015.

- Parsa, K.; Mekhiche, M.; Sarokhan, J.; Stewart, D. Performance of OPT’s Commercial PB3 PowerBuoy™ during 2016 Ocean Deployment and Comparison to Projected Model Results.

- Frandsen, J.; doblaré, M.; Rodriguez, P. Preliminary Technical Assessment of the Wavebob Energy Converter Concept; 2012.

- Payne, G.S.; Taylor, J.R.M.; Bruce, T.; Parkin, P. Assessment of Boundary-Element Method for Modelling a Free-Floating Sloped Wave Energy Device. Part 2: Experimental Validation. Ocean Engineering 2008, 35, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, G.S.; Taylor, J.R.M.; Bruce, T.; Parkin, P. Assessment of Boundary-Element Method for Modelling a Free-Floating Sloped Wave Energy Device. Part 1: Numerical Modelling. Ocean Engineering 2008, 35, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejerskog, E.; Boström, C.; Hai, L.; Waters, R.; Leijon, M. Experimental Results on Power Absorption from a Wave Energy Converter at the Lysekil Wave Energy Research Site. Renewable Energy 2015, 77, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, E.; Doherty, K.; Henry, A.; Dias, F. How Does Oyster Work? The Simple Interpretation of Oyster Mathematics. European Journal of Mechanics - B/Fluids 2014, 47, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Ai, J.; Zuo, L. Design, Fabrication, Simulation and Testing of an Ocean Wave Energy Converter with Mechanical Motion Rectifier. Ocean Engineering 2017, 136, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. A Tunable Resonant Oscillating Water Column Wave Energy Converter. Ocean Engineering 2016, 116, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, F.; Meng, X.; Fu, J. Design of the Wave Energy Converter Array to Achieve Constructive Effects. Ocean Engineering 2016, 124, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göteman, M.; Engström, J.; Eriksson, M.; Isberg, J. Optimizing Wave Energy Parks with over 1000 Interacting Point-Absorbers Using an Approximate Analytical Method. International Journal of Marine Energy 2015, 10, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F. Time Domain Prediction of Power Absorption from Ocean Waves with Wave Energy Converter Arrays. Renewable Energy 2016, 92, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.-Z.; Shi, J.; Zou, Q.-P.; Teng, B. Investigation of Hydrodynamic Performance of an OWC (Oscillating Water Column) Wave Energy Device Using a Fully Nonlinear HOBEM (Higher-Order Boundary Element Method). Energy 2015, 83, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.-Z.; Wang, R.-Q.; Zou, Q.-P.; Teng, B. An Experimental Investigation of Hydrodynamics of a Fixed OWC Wave Energy Converter. Applied Energy 2016, 168, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ning, D.; Zhang, C.; Zou, Q.; Liu, Z. Nonlinear and Viscous Effects on the Hydrodynamic Performance of a Fixed OWC Wave Energy Converter. Coastal Engineering 2018, 131, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de, O. Falcão, A.F. Wave-Power Absorption by a Periodic Linear Array of Oscillating Water Columns. Ocean Engineering 2002, 29, 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, G.; Vantorre, M.; Frigaard, P.; Beels, C.; De Rouck, J. Bottom Slamming on Heaving Point Absorber Wave Energy Devices. J Mar Sci Technol 2010, 15, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Bao, J.; Lin, Y. Design of a Hydraulic Power Take-off System for the Wave Energy Device with an Inverse Pendulum. China Ocean Eng 2014, 28, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, G.; Liu, S.; Zhao, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X. Hydrodynamic Performance Investigation of the Multi-Degree of Freedom Oscillating-Buoy Wave Energy Converter. Ocean Engineering 2023, 285, 115345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Isberg, J.; Leijon, M. Hydrodynamic Modelling of a Direct Drive Wave Energy Converter. International Journal of Engineering Science 2005, 43, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Cao, F.; Liu, Z.; Qu, N. Theoretical Study on the Power Take-off Estimation of Heaving Buoy Wave Energy Converter. Renewable Energy 2016, 86, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Xiao, L.; Peng, T. Comparative Study on Power Capture Performance of Oscillating-Body Wave Energy Converters with Three Novel Power Take-off Systems. Renewable Energy 2017, 103, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celesti, M.L.; Mattiazzo, G.; Faedo, N. Towards Modelling and Control Strategies for Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy Converters: Challenges and Opportunities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 224, 116080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristondo, O.; Ulazia, A.; Ezpeleta, H. Modeling Weights for Co-Location Feasibility in Hybrid Wind-Wave Device. Energy 2025, 337, 138548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubesch, E.; Sergiienko, N.Y.; Nader, J.-R.; Ding, B.; Cazzolato, B.; Penesis, I.; Li, Y. Experimental Investigation of a Co-Located Wind and Wave Energy System in Regular Waves. Renewable Energy 2023, 219, 119520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Collazo, C.; Greaves, D.; Iglesias, G. A Review of Combined Wave and Offshore Wind Energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 42, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer WW, Verheij FJ, Zwemmer LBV, R. Das GD. The energy island. An inverse pump accumulation station. In: Proceedings of the European wind energy conference. EWEA: Milan, Italy; 2007. p. 1–5.

- Yin, J.; Fan, Y.; Bashir, M.; Nie, D.; Lai, Y.; Ding, J.; Yu, J.; Li, C.; Yang, Y. Development of a Hybrid Deep Learning Model with HHO Algorithm for Dynamic Response Prediction of Wind-Wave Integrated Floating Energy Systems. Ocean Engineering 2025, 340, 122394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Island Ltd. Energy island web page; 2009.

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, C.; Li, D.; Shi, H. Experimental Study on the Cylindrical Oscillating Water Column Device. Ocean Engineering 2022, 246, 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Collazo, C.; Greaves, D.; Iglesias, G. Hydrodynamic Response of the WEC Sub-System of a Novel Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy Converter. Energy Conversion and Management 2018, 171, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michele, S.; Renzi, E.; Perez-Collazo, C.; Greaves, D.; Iglesias, G. Power Extraction in Regular and Random Waves from an OWC in Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy Systems. Ocean Engineering 2019, 191, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ning, D.; Shi, W.; Johanning, L.; Liang, D. Hydrodynamic Investigation on an OWC Wave Energy Converter Integrated into an Offshore Wind Turbine Monopile. Coastal Engineering 2020, 162, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, P.; Teng, B.; Bai, W.; Ning, D.; Liu, Y. Wave Power Absorption by an Oscillating Water Column (OWC) Device of Annular Cross-Section in a Combined Wind-Wave Energy System. Applied Ocean Research 2021, 107, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Collazo, C.; Greaves, D.; Iglesias, G. A Novel Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy Converter for Jacket-Frame Substructures. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry V, Babarit A. Assessment of the annual energy production of a heaving wave energy converter sliding on the mast of a fixed offshore wind turbine. Renewable Energy Congress XI (WREC XI). 2010.

- Gkaraklova, S.; Chotzoglou, P.; Loukogeorgaki, E. Frequency-Based Performance Analysis of an Array of Wave Energy Converters around a Hybrid Wind–Wave Monopile Support Structure. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, S.; Shi, H.; Ma, Q.; Li, D.; Cao, F. Hydrodynamic Analysis of a Novel Multi-Buoy Wind-Wave Energy System. Renewable Energy 2023, 219, 119477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibani, M.J.; Ketabdari, M.J. Numerical Modeling of an Innovative Hybrid Wind Turbine and WEC Systems Performance: A Case Study in the Persian Gulf. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Science 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Ma, Z.; Fan, T.; Zhai, G.; Ou, J. Experimental and Numerical Study of Hydrodynamic Responses of a New Combined Monopile Wind Turbine and a Heave-Type Wave Energy Converter under Typical Operational Conditions. Ocean Engineering 2018, 159, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, M.; Derakhshan, S.; Motawej, H. A Mathematical Model Development for Assessing the Engineering and Economic Improvement of Wave and Wind Hybrid Energy System. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Mech Eng 2020, 44, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez C, Iglesias G. Integration of wave energy converters and offshore windmills. Proc Fourth Int Conf Ocean Energy 2012:1–6.

- Gao, R.; Shi, H.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Cui, X.; Cao, F. Comparative Study on the Capture Performance of Two Wave Energy Converters Integrated into the Jacket-Frame Foundation. Ocean Engineering 2023, 289, 116226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yu, T.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Study on Hydrodynamic Characteristics of a Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy System Combing a Composite Bucket Foundation and Wave Energy Converter. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35, 087136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Bechlenberg, A.; van Rooij, M.; Jayawardhana, B.; Vakis, A.I. Modelling of a Wave Energy Converter Array with a Nonlinear Power Take-off System in the Frequency Domain. Applied Ocean Research 2019, 90, 101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, M.N.; Kluger, J.M.; Sapsis, T.P.; Slocum, A.H. A Symbiotic Approach to the Design of Offshore Wind Turbines with Other Energy Harvesting Systems. Ocean Engineering 2018, 169, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazari, A. Dynamic Response of a Combined Spar-Type FOWT and OWC-WEC by a Simplified Approach. Renewable Energy Research and Applications 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konispoliatis, D.N.; Katsaounis, G.M.; Manolas, D.I.; Soukissian, T.H.; Polyzos, S.; Mazarakos, T.P.; Voutsinas, S.G.; Mavrakos, S.A.; Konispoliatis, D.N.; Katsaounis, G.M.; et al. REFOS: A Renewable Energy Multi-Purpose Floating Offshore System. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebi, P.; M’zoughi, F.; Garrido, I.; Garrido, A.J.; Aboutalebi, P.; M’zoughi, F.; Garrido, I.; Garrido, A.J. Performance Analysis on the Use of Oscillating Water Column in Barge-Based Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. Mathematics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebi, P.; M’zoughi, F.; Martija, I.; Garrido, I.; Garrido, A.J.; Aboutalebi, P.; M’zoughi, F.; Martija, I.; Garrido, I.; Garrido, A.J. Switching Control Strategy for Oscillating Water Columns Based on Response Amplitude Operators for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines Stabilization. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubault A, Alves M, Sarmento A, Roddier D, Peiffer A. Modeling of an Oscillating Water Column on the Floating Foundation WindFloat. Volume 5: Ocean Space Utilization; Ocean Renewable Energy, Rotterdam, The Netherlands: ASMEDC; 2011, p. 235–46.

- Sarmiento, J.; Iturrioz, A.; Ayllón, V.; Guanche, R.; Losada, I.J. Experimental Modelling of a Multi-Use Floating Platform for Wave and Wind Energy Harvesting. Ocean Engineering 2019, 173, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, C.; Sueyoshi, M.; Yoshida, S. Integration of a Semisubmersible Floating Wind Turbine and Wave Energy Converters: An Experimental Study on Motion Reduction. J Mar Sci Technol 2020, 25, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Ye, X.; Wang, F.; Adcock, T.A.A.; Ning, D. Power and Dynamic Performance of a Floating Multi-Functional Platform: An Experimental Study. Energy 2023, 285, 129367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheng, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Gao, Y. Short-Term Extreme Response and Fatigue Damage of an Integrated Offshore Renewable Energy System. Renewable Energy 2018, 126, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailides, C. Hydrodynamic Response and Produced Power of a Combined Structure Consisting of a Spar and Heaving Type Wave Energy Converters. Energies 2021, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou M-R, Pan Y, Ren N-X, Zhu Y. Operational Performance of a Combined TLP-type Floating Wind Turbine and Heave-type Floating Wave Energy Converter System. Proceedings of the 2nd 2016 International Conference on Sustainable Development (ICSD 2016), Xi’an, China: Atlantis Press; 2017.

- Ren, N.; Ma, Z.; Shan, B.; Ning, D.; Ou, J. Experimental and Numerical Study of Dynamic Responses of a New Combined TLP Type Floating Wind Turbine and a Wave Energy Converter under Operational Conditions. Renewable Energy 2020, 151, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright C, Pakrashi V, Murphy J. Numerical modelling of a combined tension moored wind and wave energy convertor system. European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference (EWTEC) Series, 2017.

- Rony, J.S.; Karmakar, D. Performance of a Hybrid TLP Floating Wind Turbine Combined with Arrays of Heaving Point Absorbers. Ocean Engineering 2023, 282, 114939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, L.; Michailides, C.; Li, X. Wind–Wave Coupling Effect on the Dynamic Response of a Combined Wind–Wave Energy Converter. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhou, B.; Vogel, C.; Liu, P.; Willden, R.; Sun, K.; Zang, J.; Geng, J.; Jin, P.; Cui, L.; et al. Optimal Design and Performance Analysis of a Hybrid System Combing a Floating Wind Platform and Wave Energy Converters. Applied Energy 2020, 269, 114998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Yi, Y.; Zheng, X.; Cui, L.; Zhao, C.; Liu, M.; Rao, X. Experimental Investigation of Semi-Submersible Platform Combined with Point-Absorber Array. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 245, 114623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarlouei, M.; Gaspar, J.F.; Calvario, M.; Hallak, T.S.; Mendes, M.J.G.C.; Thiebaut, F.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental Study of Wave Energy Converter Arrays Adapted to a Semi-Submersible Wind Platform. Renewable Energy 2022, 188, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, D.; Ma, X.; Qian, P. The Influence of Power-Take-off Control on the Dynamic Response and Power Output of Combined Semi-Submersible Floating Wind Turbine and Point-Absorber Wave Energy Converters. Ocean Engineering 2021, 227, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, H.R.; Ghassemi, H.; Abbasi, A.; Vakilabadi, K.A.; Yazdi, H.; He, G. Novel Concept of Hybrid Wavestar- Floating Offshore Wind Turbine System with Rectilinear Arrays of WECs. Ocean Engineering 2022, 262, 112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W. , Wang, Y., Shi, W., Michailides, C., Wan, L., Chen, M. Numerical study of hydrodynamic responses for a combined concept of semisubmersible wind turbine and different layouts of a wave energy converter. Ocean Engineering 2023, 272, 113824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. , Hu, J., Jin, P., Sun, K., Li, Y., Ning, D. Power performance and motion response of a floating wind platform and multiple heaving wave energy converters hybrid system. Energy 2023, 265, 126314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, E. , Panahi, S. , Ghassemi, H., He, G., Liu, P. Power absorption of combined wind turbine and wave energy converter mounted on braceless floating platform. Ocean Engineering 2022, 266, 113027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, G. Wave power: an overview of recent international developments and potential US projects (1996).

- Brooke, J. Wave energy conversion, Elsevier (2003).

- Veigas, M.; Iglesias, G. Wave and Offshore Wind Potential for the Island of Tenerife. Energy Conversion and Management 2013, 76, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veigas, M.; Carballo, R.; Iglesias, G. Wave and Offshore Wind Energy on an Island. Energy for Sustainable Development 2014, 22, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veigas, M.; Iglesias, G. A Hybrid Wave-Wind Offshore Farm for an Island. International Journal of Green Energy 2015, 12, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimirad, M. Offshore energy structures: for wind power, wave energy and hybrid marine platforms, Springer (2014).

- Hansen, KE. Floating power plant Poseidon; 2017. https://www.knudehansen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Floating-Power-Plant-Poseidon-07064_10035.pdf. [[Accessed 11 November 2025].

- Tethys, Poseidon floating power (Poseidon 37), Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; n.d. https://tethys.pnnl.gov/project-sites/poseidon-floating-power-poseidon-37. [Accessed 11 November 2025]. 11 November.

- Marine Power Systems. A front cover for DualSub; n.d. https://www.marinepowersystems.co.uk/a-front-cover-for-dualsub/.[Accessed 11 November 2025]. 11 November.

- Bombora Wave. Testing of a floating hybrid energy platform; n.d. https://bomborawave.com/latest-news/testing-of-a-floating-hybrid-energy-platform/. [Accessed 11 November 2025]. 11 November.

- Pelagic Power. About pelagic power. n.d. http://www.pelagicpower.no/about.html. [Accessed 11 November 2025].

- Noviocean. Noviocean wave energy converter, n.d. Noviocean. Noviocean wave energy converter, n.d. https://noviocean.energy/. [Accessed 11 November 2025].

- Perez-Collazo, C.; Pemberton, R.; Greaves, D.; Iglesias, G. Monopile-Mounted Wave Energy Converter for a Hybrid Wind-Wave System. Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 199, 111971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Cao, L.; Liu, G.; Guo, H. Hydrodynamic Performance of an Oscillating Water Column Integrated into a Hybrid Monopile Foundation. Ocean Engineering 2024, 299, 117062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cui, L.; Bhattacharya, S. A Novel Foundation Design for the Hybrid Offshore Renewable Energy Harvest System. Ocean Engineering 2025, 323, 120519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, G.; Vantorre, M.; Beels, C.; De Rouck, J.; Frigaard, P. Power Absorption by Closely Spaced Point Absorbers in Constrained Conditions. IET Renewable Power Generation 2010, 4, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Proposal and Layout Optimization of a Wind-Wave Hybrid Energy System Using GPU-Accelerated Differential Evolution Algorithm. Energy 2022, 239, 121850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, P.; Cui, L.; Cheng, L. Optimization of an Annular Wave Energy Converter in a Wind-Wave Hybrid System. J Hydrodyn 2023, 35, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, B.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Optimization and Evaluation of a Semi-Submersible Wind Turbine and Oscillating Body Wave Energy Converters Hybrid System. Energy 2023, 282, 128889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, M.; Qin, R.; Luo, E.; Duan, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L. Extracted Power Optimization of Hybrid Wind-Wave Energy Converters Array Layout via Enhanced Snake Optimizer. Energy 2024, 293, 130529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.M.; Shehata, A.S.; Elbatran, A.H.; Kotb, M.A. Numerical Optimization of Hybrid Wind-Wave Farm Layout Located on Egyptian North Coasts. Ocean Engineering 2021, 234, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haces-Fernandez, F.; Li, H.; Ramirez, D. A Layout Optimization Method Based on Wave Wake Preprocessing Concept for Wave-Wind Hybrid Energy Farms. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 244, 114469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wei, C.; Wang, D.; Xue, G. Hydrodynamic Analysis and Optimisation of a Novel Wind-Wave Hybrid System Combined with the Semi-Submersible Platform and Various Wave Energy Converters. Energy 2025, 330, 136697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WECs | Oscillating Bodies | Oscillating Water Column | Overtopping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working principle | Utilizing reciprocating body motion of waves | Air turbine driven by air compressed by wave energy | Hydro, air, or hydraulic type turbine driven by wave energy |

| Name | Wind turbine type | Wind turbine power capacity (MW) | WEC type | WEC power capacity (MW) | Status |

| Poseidon P37[131] | Semi-sub | 3*0.011 | Heaving | 10*0.003 | Sea test in 2012-2013 |

| P80[132] | Semi-sub | 4-10 | Heaving | 2-3.6 | 1:30 scale tested in 2022 |

| DualSub[133] | Semi-sub | 2 | Heaving | 0.5 | N/A |

| InSPIRE[134] | Semi-sub | 8-12 | Pressure | 4/6 | Scaled testing in 2022 |

| W2Power[135] | Semi-sub | 2*3.6 | Heaving | 18*0.1 | 1:3 scale tested in 2008 |

| NoviOcean[136] | Barge | 3*0.05 | Heaving | 0.65 | 1:3 scale tested in 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).