1. Introduction

The hospitality industry is undergoing a rapid and structural transformation driven by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and smart technologies. Hotels increasingly deploy AI-powered concierges, service robots, mobile check-in systems, predictive analytics, and in-room voice assistants to enhance operational efficiency, personalize guest experiences, and address workforce shortages (Marghany et al. 2025; Ren et al. 2025). The adoption of such technologies accelerated markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic, when digital and contact-light service processes became essential for reducing physical interactions and maintaining operational continuity (Kim et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2021). As AI continues to develop, understanding how guests evaluate these innovations has become strategically important for the future competitiveness and sustainability of hotel operations.

Despite significant technological progress, guest acceptance remains uneven and often ambivalent. While some travelers value the convenience, efficiency, and novelty of smart and AI-enabled services, others express reservations related to impersonality, reduced human warmth, job displacement, and the loss of emotional connection traditionally associated with hospitality encounters (Gursoy 2025; Kang et al. 2023). Privacy and data-security concerns amplify this ambivalence: many guests hesitate to adopt systems requiring behavioral or personal data, citing fears of surveillance, profiling, or misuse (Jia et al. 2024; Hu and Min 2025). These tensions underline a practical dilemma: if guests do not accept AI-enabled services, investments risk underuse, reputational challenges, and strategic misalignment, particularly in emerging markets, where digital transformation is still consolidating and guest exposure to advanced smart technologies varies widely.

Albania provides a compelling context for examining these issues. As one of the fastest-growing tourism destinations in the Western Balkans, the country has experienced rapid increases in international arrivals and substantial investment in accommodation infrastructure. Yet the integration of smart and AI-enabled systems in Albanian hotels remains at an early developmental stage, characterized by heterogeneous adoption, unequal technological readiness, and limited guest familiarity. This combination of strong tourism growth and emergent digitalization makes Albania an ideal empirical setting for studying how guests evaluate AI-enabled hospitality services when exposure, expectations, and cultural norms are still forming. Moreover, understanding acceptance dynamics in such settings can inform both local managerial strategies and broader debates about AI adoption in developing and transitional tourism markets.

The academic literature offers important insights, but significant gaps remain. Foundational models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis 1989) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT/UTAUT2) (Venkatesh et al. 2003; Venkatesh et al. 2012) emphasize utilitarian determinants, usefulness and ease of use. More recent hospitality frameworks, including the Service Robot Acceptance Model (SRAM), incorporate anthropomorphism, trust, social presence, and emotional expectations (Shum et al. 2024; Chi et al. 2023). Yet most existing studies examine one technology at a time, focus on specific contexts (e.g., robots, kiosks, or chatbots), or rely on highly technologically developed markets. Little is known about how multiple experiential, ethical, interpersonal, and cultural considerations jointly shape guest acceptance in emergent hospitality ecosystems, where exposure to AI technologies remains limited.

A second gap concerns value perceptions and financial willingness. While some studies examine behavioral intentions, far fewer investigate whether guests are willing to pay more for AI-enhanced services, a key managerial consideration as hotels weigh the costs and benefits of technological investment. A third gap relates to interaction effects: although concerns about depersonalization are well documented, little empirical research has examined whether trust in AI can buffer or moderate these concerns.

To address these gaps, this study develops and tests a comprehensive framework integrating three complementary domains. The first domain encompasses core acceptance drivers, including utilitarian evaluations, experiential familiarity, and awareness of AI-enabled hospitality technologies. The second domain addresses human and ethical dimensions, such as trust in AI, privacy and data-handling concerns, and interpersonal expectations regarding warmth and human interaction. The third domain captures contextual and value-based considerations, particularly cultural–linguistic fit and guests’ willingness to pay for AI-enhanced services. Together, these dimensions allow for an integrated perspective that goes beyond narrow, single-construct models. The empirical analysis focuses on two ordered behavioral outcomes: whether smart or AI technologies influence hotel choice and whether guests are willing to pay more for AI-enabled services, reflecting both attitudinal and financial acceptance.

Building on this conceptual foundation, the study investigates five research questions (RQs), each linked to theoretically grounded hypotheses (Hs).

RQ1 examines experiential and awareness-related determinants of acceptance. Correspondingly, H1 proposes that guests with prior smart/AI hotel experience exhibit higher acceptance, while H2 posits that greater awareness of AI technologies increases acceptance, particularly willingness to pay.

RQ2 considers how trust, privacy, and ethical concerns shape guest responses. H3 asserts that higher trust in AI and responsible data handling increases acceptance, whereas H4 predicts that privacy concerns reduce strong acceptance, especially financial willingness.

RQ3 investigates how perceived value influences behavioral intentions and financial readiness. H5 states that perceiving more benefits and desirable features increases acceptance and willingness to pay, while H6 predicts that privacy concerns suppress willingness to pay more strongly than general interest.

RQ4 addresses interpersonal and cultural expectations. H7 suggests that lower digital familiarity is associated with reduced acceptance, H8 notes that preference for human interaction may relate ambiguously to acceptance, and H9 proposes that better cultural–linguistic fit enhances acceptance.

Finally, RQ5 examines interaction mechanisms. H10 hypothesizes that trust weakens the negative effect of perceived loss of personal touch on acceptance.

By integrating these conceptual streams and applying cumulative link models, partial proportional-odds models, nonlinear extensions, and robustness checks to a large in-person survey conducted in Albania, the study provides new empirical evidence on how guests in emerging markets evaluate AI-enabled hospitality services. The findings contribute to the literature by (1) offering a unified, multi-domain framework that incorporates experiential, ethical, interpersonal, and cultural influences; (2) addressing financial acceptance as a distinct and managerially relevant outcome; and (3) identifying interaction mechanisms, particularly involving trust, that shape how guests negotiate trade-offs between convenience, ethical confidence, and interpersonal expectations. These insights offer practical relevance for researchers and practitioners designing ethically transparent, culturally adaptive, and guest-centered AI-enabled hospitality services in Albania and comparable emerging destinations.

2. Literature Review

Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly become one of the most transformative forces shaping contemporary hospitality services. Hotels increasingly deploy AI-enabled systems such as intelligent check-in kiosks, natural-language chatbots, predictive recommendation engines, facial-recognition entry, voice-controlled smart rooms, and automated service fulfillment. These technologies rely on machine learning, natural language processing, and real-time data analytics to enhance convenience, streamline interactions, and support personalized service delivery (Tussyadiah 2020; Buhalis & Leung 2018; Ivanov and Webster 2019). As these systems expand across both front-stage and back-stage operations, understanding how guests form evaluations and intentions toward AI-enabled hospitality services has become a central research priority (Mariani & Borghi 2023; Huang and Rust 2018).

Within this context, the literature highlights three broad domains: utilitarian-experiential foundations, human–social and ethical considerations, and contextual value assessments, that align closely with the constructs measured in this study. The following sections review these domains using terminology parallel to the survey instrument and analytical framework.

2.1. Core Acceptance Drivers: Utilitarian, Experiential, and Prior Experience

Technology acceptance theories such as TAM (Davis 1989) and UTAUT/UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al. 2003; 2012) consistently emphasize functionality, performance expectancy, and ease of use as foundational drivers of technology adoption. In AI-enabled hospitality, these drivers typically manifest as perceived improvements in convenience, speed, and personalization, shaping guests’ evaluations of whether AI-enabled services are useful, reliable, and conducive to a smooth hotel experience (Gursoy et al. 2019); Prentice et al. 2020). Operationally, such gains are reflected in technology-mediated guest journeys, where self-service interfaces reduce perceived waiting burdens at check-in (Kokkinou & Cranage 2013), AI-supported personalization strengthens the perceived relevance of recommended services (Makivić et al. 2024), and smart-hotel attributes include in-room control features (e.g., lighting/room settings) that enhance convenience and perceived performance (Kim et al. 2020).

Consistent with this theoretical foundation, awareness of smart and AI-enabled technologies emerges as an important antecedent of acceptance. Awareness can shape expectations about functionality and reduce ambiguity by helping individuals understand what AI systems can do and when they are appropriate to use. In tourism and hospitality contexts, evidence also indicates that consumers differ substantially in their familiarity with AI tools and in the benefits/disadvantages they attribute to them, supporting the premise that knowledge and awareness condition subsequent evaluations and intentions (Sousa et al. 2024).

Similarly, prior smart/AI hotel experience is expected to predict acceptance because experiential familiarity reduces uncertainty and increases confidence in navigating technology-mediated service encounters. In smart-hotel research, perceived usefulness and ease of use are empirically linked to technology amenities and visiting intentions, supporting the role of direct exposure and learning-by-using in strengthening acceptance (Yang et al. 2021). Related evidence from AI personalization in hotels also shows that technological experience is integral to how guests evaluate AI-enabled value creation and service outcomes (Makivić et al. 2024).

Perceived value plays a central role in shaping both attitudinal and financial acceptance. In this study, value is operationalized through the number of perceived benefits associated with AI-enabled hospitality services and the number of desired AI features guests would like hotels to adopt. These measures reflect functional, emotional, and epistemic value dimensions commonly identified in hospitality technology research (Mariani and Borghi 2021; Prentice et al. 2020). Perceived benefits include convenience, speed, personalization, multilingual assistance, and enhanced accuracy, while desired features capture interest in additional AI capabilities such as smart-room automation, predictive recommendations, or enhanced check-in efficiency (Said 2023). Research consistently shows that guests who identify more benefits or express interest in more AI features demonstrate higher acceptance and greater willingness to pay (Ivanov & Webster 2024).

Collectively, awareness, prior experience, and perceived value, captured through perceived benefits and desired features, represent the utilitarian and experiential core of AI acceptance.

2.2. Human and Social Dimensions: Interaction, Trust, and Ethics

AI-enabled hospitality interactions are shaped not only by functional evaluations but also by human–social and ethical expectations. Hospitality is a service domain where warmth, empathy, and human interaction traditionally play central roles (Barnes et al. 2020). Accordingly, constructs such as trust in AI, privacy concerns, perceived loss of personal touch, and support for human–AI collaboration capture the interpersonal and ethical evaluations that shape adoption.

Trust in AI, defined as confidence in the accuracy, fairness, responsibility, and data-handling competence of AI systems, is widely recognized as one of the strongest determinants of acceptance (Wirtz et al. 2018; Hoffman et al. 2013). When guests trust that AI systems operate reliably and ethically, they experience lower uncertainty and are more likely to rely on AI-enabled services. Trust also reduces perceived risk in contexts involving sensitive information or automated decision-making (McLean et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2020).

Conversely, privacy concerns represent a major inhibitor of AI adoption. Because AI systems often rely on personal, behavioral, or biometric data, guests frequently worry about how information is collected, stored, and used (Culnan & Armstrong 1999; Morosan and DeFranco 2015). Privacy concerns have especially strong effects on financial acceptance suppressing willingness to pay for AI-enabled services even among guests who express general curiosity or mild interest. This aligns directly with the operationalization used in this study.

Interpersonal expectations further shape acceptance. Perceived loss of personal touch, measured directly in the survey, captures concerns that AI interactions may feel less warm, less empathetic, or less emotionally attuned. These concerns often arise in interactions involving chatbots, automated recommendations, or standardized AI responses. Research shows that such interpersonal reservations may not always reduce acceptance directly but may influence how guests interpret other constructs, such as trust (Kang et al. 2023).

This is especially relevant for the interaction mechanism tested in the present study, where trust in AI is hypothesized and found to weaken the negative implications of perceived loss of personal touch. Prior literature supports this buffering effect: trust can mitigate concerns about depersonalization by increasing comfort with automated interactions (Wirtz et al. 2018).

Finally, support for human–AI collaboration captures attitudes toward hybrid service models in which AI augments rather than replaces staff. Studies show that guests often prefer AI systems that assist employees (e.g., by automating routine tasks or providing real-time recommendations), enabling staff to focus on emotional labor and personalized service (Tuomi et al. 2021; Ivanov and Webster 2024). This construct aligns with the collaborative-service logic embedded in the instrument.

Together, these human–social and ethical constructs reflect a multidimensional evaluation that goes beyond functionality and addresses the relational and emotional expectations that define hospitality.

2.3. Contextual and Value Considerations: Cultural Fit and Willingness to Pay

Acceptance of AI-enabled hospitality services also depends on contextual and cultural fit. Cultural–linguistic fit, measured as the perceived alignment between AI system communication and local language or cultural norms, plays a critical role in shaping comfort and trust (Holmqvist et al. 2017) AI interactions that reflect appropriate language structures, politeness norms, and culturally sensitive communication patterns are perceived as more natural and reliable. Conversely, poorly localized AI outputs may generate friction, reduce perceived authenticity, or signal technological immaturity, especially in emerging markets (Mariani and Borghi 2023).

These contextual perceptions shape behavioral outcomes. In this study, acceptance is operationalized through two distinct behavioral and financial outcomes: whether AI-enabled services influence hotel choice and whether guests are willing to pay more for such services. These measures align with the hospitality literature, which distinguishes between attitudinal interest and financial readiness (Prentice et al. 2020).

The privacy calculus framework predicts that perceived benefits increase both outcomes, whereas privacy concerns suppress them, particularly willingness to pay (Culnan and Armstrong 1999; Morosan and DeFranco 2015). Similarly, cultural–linguistic fit enhances both behavioral acceptance and perceived value, contributing to guests’ readiness to support AI-integrated experiences (Ren et al. 2025).

These insights emphasize that AI acceptance is not solely a matter of technical performance but depends on cultural resonance, ethical confidence, and perceived value relative to cost.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Context

This study investigates hotel guests’ acceptance of smart and AI-enabled technologies in accommodation settings. A cross-sectional quantitative survey design was employed, consistent with methodological approaches in hospitality-technology and AI-acceptance research that emphasize structured behavioral-intention modelling (Chiu and Chen 2025; Ozturk et al. 2023; Ren et al. 2025; Soliman et al. 2025). The conceptual framework integrates multiple theoretical streams. First, technology-acceptance perspectives from TAM (Davis 1989) and UTAUT/UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al. 2012) inform the utilitarian foundations of the instrument. Second, human–social dimensions of technology-mediated service encounters: trust, privacy, perceived loss of human touch, and preferences for interpersonal interaction, draw on empirical research in service automation and AI-enabled hospitality contexts (Wirtz et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2021; Lin and Mattila 2021). Third, contextual and cultural value considerations, including cultural–linguistic fit and support for human–AI collaboration, reflect emerging literature on service-ecosystem adaptation (Holmqvist et al. 2014; Holmqvist et al. 2017; Ivanov et al. 2022).

Within this integrated framework, the study investigates two ordered behavioral outcomes: whether smart or AI-enabled features influence hotel choice and whether guests are willing to pay more for such services. Both outcomes were measured as three-category ordinal variables and analyzed using cumulative link models (CLMs) and, where necessary, partial proportional-odds models (PPOMs), which are appropriate for ordinal data and enable direct modelling of category transitions (Agresti 2010; Christensen 2023; Peterson & Harrell 1990).

The empirical setting is Tirana, the capital of Albania, a rapidly expanding tourism hub in the Western Balkans where the adoption of smart and AI-enabled systems in accommodation remains emergent. Skanderbeg Square, the city’s central plaza, was selected due to its heterogeneous, high-footfall mix of domestic and international visitors, providing access to diverse respondents rather than a statistically representative population. To avoid overstating generalizability, claims of representativeness were deliberately avoided, and the non-probability nature of the sampling design is explicitly acknowledged in the Discussion.

3.2. Instrument Development and Constructs

The survey instrument, Guest Acceptance of Smart and AI Technologies in Hospitality, was developed following an extensive review of contemporary hospitality-technology research and empirical studies on AI-enabled service encounters, robotics, and digital guest experiences. TAM and UTAUT/UTAUT2 informed the utilitarian determinants. Research on hedonic motivation, trust, privacy, ethics, and anthropomorphism guided the human–social domain (Wirtz et al. 2018); (Lin & Mattila 2021); (Kim et al. 2021). Cultural adaptation and human–AI collaboration items were designed in line with service-ecosystem and cultural-fit literature (Holmqvist et al. 2017; Ivanov and Webster 2019).

Items from validated scales were adapted where applicable and examples of adapted constructs (e.g., trust, privacy, human-interaction importance) are documented in

Table A1 to ensure transparency. For constructs lacking validated measures, particularly cultural fit and support for AI–staff collaboration, items were developed following best-practice guidelines for clarity and non-leading wording (Dillman et al. 2015). Content and face validity were strengthened via expert review by two hospitality-technology academics and a pilot test (N = 20), which confirmed comprehension and resulted in minor refinements.

The final questionnaire contained four conceptual blocks: (a) awareness and experience, (b) perceived benefits and desired features, (c) ethical–human–trust evaluations, and (d) behavioral outcomes. A full list of all items, response formats, and variable names is provided in

Table A1 (Appendix).

3.3. Measurement Model and Reliability Considerations

The survey instrument comprised utilitarian, experiential, and ethical constructs measured using single-item evaluations, Likert-type items, and multi-response checklists. The study employed ordinal and logistic regression models rather than a latent-variable SEM framework; consequently, constructs were operationalized through theoretically appropriate single-item or formative indicators. Item specifications and coding rules are detailed in

Table A1 and in the accompanying reproducible R script (

Code S1, Supplementary, Materials).

Several constructs, including trust in AI, cultural-linguistic fit, privacy concern, and perceived loss of personal touch, were intentionally designed as single, conceptually narrow items. Psychometric research supports the use of single-item measures when the underlying construct is narrow, unambiguous, and readily understood by respondents (Bergkvist & Rossiter 2007; Fuchs & Diamantopoulos 2009). Because these constructs were measured with single items, internal-consistency reliability indices (e.g., Cronbach’s α or McDonald’s ω) and related multi-indicator metrics (e.g., composite reliability) were not applicable and were therefore not reported (DeVellis 2017; Tavakol & Dennick 2011; Fuchs & Diamantopoulos 2009).

Perceived benefits and desired features were collected through multi-response selection lists. These were treated analytically as formative “breadth indicators,” where each selected option contributes distinct information about perceived value and omissions do not constitute measurement error.

Likert-type (1–5) evaluations of comfort with AI, trust, human-interaction importance, cultural fit, and support for human–AI collaboration were treated as approximately interval-scaled. This approach aligns with methodological evidence that common parametric procedures are generally robust for Likert-type responses, especially when sample sizes are moderate-to-large and/or items are aggregated into scales, often yielding inferences comparable to nonparametric alternatives (Harpe 2015; Norman 2010; Sullivan & Artino 2013). Tri-level items, such as privacy concern, perceived loss of personal touch, awareness, and prior AI experience, were coded on an ordered 0–2 scale to preserve ordinal meaning for subsequent ordinal modelling.

All preprocessing steps including harmonization of categorical variables, construction of indicator variables, generation of formative breadth counts, and creation of ordinal and binary outcomes, are comprehensively documented in the reproducible R script (

Code S1, Supplementary, Materials). Descriptive distributions, missing-data patterns, and pairwise correlations were examined to verify the expected behavioral and attitudinal structure prior to model estimation.

3.4. Sample and Data Collection

Data were collected between May and October 2025 using an intercept survey administered face-to-face by trained undergraduate students from the University of Tirana. Respondents were screened to ensure that they had recently stayed in a hotel or planned to do so during their current visit. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and all respondents provided informed consent.

Survey administration was conducted digitally via Google Forms, accessed through QR codes or tablets provided by the students team. This ensured immediate electronic capture, minimized transcription errors, and allowed real-time monitoring for data quality. A total of 689 complete responses were collected. After excluding cases with missing dependent-variable values, analytic subsamples consisted of N_infl = 687 for the influence-on-choice models, N_wtp = 687 for willingness-to-pay models, and N_both = 686 for joint analyses.

The voluntary, intercept-based data collection conducted in a public urban space introduces potential self-selection and time-of-day or day-of-week sampling biases. Because no weighting adjustments were feasible, these limitations are explicitly acknowledged in the Discussion.

All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the University of Tirana and adhered to principles of anonymity, voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw at any time.

3.5. Data Preparation and Coding

Data preparation followed standard analytical procedures and was conducted using a fully scripted workflow to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Raw responses were screened for completeness and inconsistencies, and missing patterns were examined descriptively. Categorical variables were harmonized across all items. Tri-level evaluative items such as privacy concerns, perceived loss of personal touch, awareness of smart technologies, and prior AI experience were recoded into ordered 0–2 formats to preserve ordinal distinctions.

Likert-type items (1–5) capturing comfort with AI, trust in AI, human-interaction importance, cultural-linguistic fit, and support for AI–staff collaboration were treated as approximately interval-scaled. This practice is supported by methodological research showing that parametric analyses applied to Likert-type measures are robust in samples of this size (Norman 2010; Harpe 2015; Sullivan & Artino 2013). The use of numeric codings for these items does not affect the ordinal-logit modeling of dependent variables, which remain strictly ordinal.

Multiple-response questions assessing perceived benefits and desired smart or AI features were converted into binary indicators for each selected option and aggregated into two count variables representing the breadth of perceived value (n_benefits and n_features). These indicators reflect the number of selections made rather than a reflective latent construct.

The two primary behavioral outcomes were recoded as ordered factors: infl_choice3 (No / Unsure / Yes) reflecting whether smart or AI technologies influence hotel choice, and wtp3 (No / Depends / Yes) capturing willingness to pay more for AI-enabled services. In addition, binary “top-box” indicators (infl_yes, wtp_yes) were created for robustness analyses focusing exclusively on unequivocal acceptance, with acknowledgment that dichotomization reduces information but enhances interpretability in robustness checks.

Demographic variables, including age group, gender, and hotel-stay frequency, were recoded into harmonized categories with explicit handling of missing responses. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, minima, maxima) were generated for all numeric predictors, and frequency distributions were produced for categorical and ordinal variables. Pearson correlation matrices were computed for the numeric codings; the decision not to compute polychoric correlations is justified because no factor analysis was conducted and the models relied on ordinal regression frameworks.

3.6. Statistical Modelling Strategy

The modelling strategy followed a sequential structure aligned with the conceptual organization of the questionnaire. Both behavioral outcomes: whether smart and AI technologies influence hotel choice and whether guests are willing to pay more, were measured using three ordered response categories. Cumulative link models (CLMs) with a logit link (i.e., proportional-odds models) were therefore used as the primary analytical framework, as they are well-suited to ordinal outcomes and estimate cumulative odds across ordered thresholds (Agresti 2010; Christensen 2023; McCullagh 1980).

The first stage estimated parsimonious baseline models (A1, A2) incorporating core determinants of technology acceptance, including awareness of smart technologies, prior AI-related experience, comfort with AI, perceived value (captured through the breadth of selected benefits and features), and demographic factors. Ethical and privacy-related constructs: privacy concerns and perceived reduction of personal touch, were added in the second stage (B1, B2) to assess whether reservations related to surveillance, data protection, or diminished human warmth attenuate acceptance independently of utilitarian evaluations. These factors are well established as inhibitors of service-technology adoption (Wirtz et al. 2018; McLeay et al. 2021; Jia et al. 2024; Lv et al. 2025).

Full attitudinal models (C1, C2) incorporated broader human–social and cultural factors: trust in AI to manage personal data, the importance placed on human interaction during hotel stays, cultural–linguistic fit, and support for human–AI collaboration. Including these constructs enabled a comprehensive assessment of whether cultural alignment, interpersonal expectations, and ethical considerations shape acceptance of AI-enabled hospitality services.

For each CLM, the proportional-odds assumption was evaluated using nominal tests. When predictors violated the proportional-odds (parallel-slopes) assumption, partial proportional-odds models were fitted within the VGAM vector generalized linear modeling framework (Peterson & Harrell 1990; Yee 2010). PPOMs retain the ordinal structure of CLMs while allowing selected coefficients to vary across thresholds, yielding a more flexible model when parallel slopes are not supported empirically.

Robustness checks were conducted using binary logistic regressions for the top-box outcomes (infl_yes, wtp_yes), which isolate respondents expressing unequivocal acceptance. Model adequacy was evaluated using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and McFadden’s pseudo-R2 (Akaike 1974; McFadden 1974). Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs), (O’brien 2007; Fox & Monette 1992; Liu & Zhang 2018; Greenwell et al. 2018). and ordinal-model diagnostics were examined using surrogate residuals to assess fit and detect potential outliers or influential observations.

Nonlinearities were examined by including centered quadratic terms for n_benefits and n_features (models D1, D2). Interaction models (E1, E2) tested whether trust moderated the effect of perceived loss of personal touch, with predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals computed to aid interpretation.

Finally, open-ended recommendations were analyzed using a lightweight text-mining procedure. Responses were tokenized, stop-words were removed, and unigram and bigram frequencies were computed to identify salient themes that complement the quantitative findings.

3.7. Software, Transparency, and Reproducibility

All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team 2024) using widely adopted and well-documented packages for data import, preprocessing, ordinal modelling, diagnostics, visualization, and text processing. Data were imported with readxl and prepared using the tidyverse ecosystem (e.g., dplyr, tidyr, stringr, forcats, tibble) (Wickham et al. 2019). Ordinal outcomes were analysed using cumulative link models implemented in ordinal (Christensen 2023) and, where proportional-odds violations required relaxation, partial proportional-odds models were estimated using VGAM (Yee 2010). Diagnostic procedures drew on car. Visualizations were produced with ggplot2 (Wickham 2016). Open-ended recommendations were processed using tidy text-mining workflows with tidytext (Silge & Robinson 2016).

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, the complete data-cleaning and modelling workflow, including all recoding rules, derived-variable construction, model specifications, diagnostics, robustness checks, and exported outputs, was documented in a fully reproducible R script provided in

Code S1, Supplementary Materials. The script covers the full pipeline from raw data import to final model estimation, including the construction of derived measures, estimation of baseline and extended ordinal models, proportional-odds diagnostics, PPOM estimation, binary logistic robustness checks, nonlinearity and interaction assessments, and text-mining routines. Key outputs (e.g., descriptive statistics, correlation matrices, CLM/PPOM estimates, diagnostic tests, and text-mining frequency tables) are included in tabular form.

The study followed ethical standards for social-science research and adhered to responsible practices in the use of artificial intelligence. Generative AI tools were used exclusively for language refinement and organizational editing of the manuscript. No generative AI systems were used for data handling, model estimation, statistical analysis, or interpretation, in line with emerging best-practice recommendations for AI-assisted academic writing (Porsdam Mann et al. 2024).

5. Discussion

This study examined the determinants of hotel guests’ acceptance of smart and AI-enabled technologies through an integrated framework combining utilitarian, experiential, ethical, and cultural considerations. Two ordered behavioral outcomes: whether AI influences hotel choice and willingness to pay a premium, were analyzed through cumulative link models, partial proportional-odds models where necessary, nonlinear and interaction extensions, and binary robustness checks. The overall pattern of findings provides consistent empirical support for several of the proposed hypotheses, while also highlighting boundaries and contingencies in guests’ acceptance of AI-enabled hospitality services. As the empirical work was conducted in Albania, fast-growing but digitally emergent tourism market, the findings are particularly informative for understanding acceptance dynamics in settings where technological exposure and expectations are still developing.

5.1. Experiential and Awareness Factors

The results offer strong support for H1, indicating that prior experience with smart or AI-enabled hotels is a robust and stable predictor of acceptance across all modeling frameworks. This aligns with previous research emphasizing the role of experiential familiarity in reducing uncertainty and strengthening perceived usefulness in service technologies (Tavitiyaman et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2021; Venkatesh et al. 2003). The positive association between awareness of smart technologies and acceptance, especially willingness to pay, supports H2 and suggests that informational exposure may increase both perceived feasibility and perceived value.

These findings can be interpreted through (Rogers 2003) Diffusion of Innovations framework. Guests with prior smart-hotel experience can be viewed as more likely to belong to earlier adopter segments (innovators/early adopters/early majority) because they have already encountered and used AI-enabled services. In settings where such technologies are still emerging, the effect of direct exposure is consistent with Rogers’ concept of trialability, whereby opportunities to experiment with an innovation reduce uncertainty and perceived risk and can accelerate adoption intentions.

Likewise, the significant role of awareness aligns with the knowledge stage of the innovation-decision process, in which individuals first become informed about an innovation before developing more favorable evaluations and adoption intentions.

Notably, awareness predicted willingness to pay more strongly than general acceptance, suggesting that informational exposure may operate differently across behavioral outcomes. While classical diffusion models treat knowledge acquisition as a precondition for attitude formation broadly, the present findings indicate that awareness may be particularly consequential when financial commitment is required, a nuance that extends existing theoretical frameworks. In an emerging destination such as Albania, where guest familiarity varies widely, and exposure to AI-enabled hospitality remains uneven, these experiential and informational factors appear especially decisive. The results suggest that increasing public awareness through demonstrations, showcasing real-world applications, and facilitating low-risk trial opportunities may be critical strategies for accelerating responsible AI adoption in such markets.

5.2. Trust, Privacy, and Ethical Evaluations

The results strongly confirm H3, showing that trust in AI, particularly trust in data handling, emerges as one of the most influential predictors in both outcomes. This aligns with service-automation research showing that trust mitigates perceived risk and increases behavioral intentions toward AI-enabled services (Della Corte et al. 2023; Pavlou 2003). Notably, the trust measure employed in this study primarily captures what the literature identifies as integrity and benevolence dimensions of trust, specifically confidence that hotels will handle personal data responsibly and ethically (Mayer et al. 1995). Other trust facets, such as competence trust (belief in AI’s functional capability to deliver quality service), were not directly measured. Future research could examine whether these distinct trust dimensions exert independent or interactive effects on acceptance, potentially revealing more nuanced pathways through which trust shapes guest responses to AI-enabled hospitality services.

The evidence for H4 is also clear: privacy concerns consistently dampen the likelihood of strong endorsement in both ordinal and binary models. However, the impact is asymmetrical, affecting “Yes” responses more strongly than “No” versus “Depends.” This selective suppression can be understood through the lens of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), which posits that perceived losses loom larger than equivalent gains in decision-making under uncertainty. When guests contemplate firm commitment to AI-enabled services, privacy risks may become psychologically salient in ways they do not when responses remain tentative or exploratory. Construal level theory offers a complementary explanation: abstract, non-committal responses (“Un-sure” or “Depends”) involve distant, low-level construal where privacy risks remain cognitively peripheral, whereas concrete endorsement (“Yes”) triggers proximal, high-level construal that foregrounds specific concerns about data vulnerability and surveillance (Morosan & DeFranco 2015; Lee & Cranage 2011; Karwatzki et al. 2017). The PPOM results further demonstrate that privacy effects violate the proportional-odds assumption, indicating heterogeneous effects across response thresholds, which strengthens the argument that privacy concerns function as threshold-based inhibitors that disproportionately reduce strong acceptance rather than uniformly shifting attitudes across the response scale.

The correlation between trust and privacy concerns observed in this study suggests that these constructs may function as reciprocal or countervailing forces rather than independent predictors. High trust may buffer privacy concerns by reducing perceived vulnerability to data misuse, while unaddressed privacy concerns may progressively erode trust over time. This dynamic interplay has practical implications: interventions aimed at building trust through transparent data governance may indirectly attenuate privacy-related resistance, offering hotels a dual pathway for enhancing acceptance. However, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes causal inference regarding the directionality of this relationship, and it remains possible that privacy-concerned guests differ systematically in unmeasured ways, such as general technology skepticism or dispositional anxiety, that confound the observed associations.

In terms of practical significance, the odds ratios for trust (OR ≈ 1.41–1.49 across models) and privacy concerns (OR ≈ 0.68 for willingness to pay) (

Table S6,

Supplementary Materials), indicate substantively meaningful effects. A one-unit increase in trust corresponds to approximately 40–50% higher odds of endorsing AI influence on hotel choice or willingness to pay a premium, while elevated privacy concerns reduce the odds of financial willingness by roughly one-third. These magnitudes suggest that trust-building and privacy mitigation represent strategically important levers for hospitality managers, not merely statistically detectable but practically modest associations.

The Albanian context adds further interpretive depth to these findings. Albania established a national personal data protection framework with Law No. 9887 on Protection of Personal Data 2008, which was later amended, and more recently adopted Law No. 124/2024 On Personal Data Protection 2024 as part of a broader alignment with EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Despite this formal framework, institutional reports indicate that enforcement capacity and public awareness of data rights have historically lagged behind many EU member states (Albania 2020 Report SWD(2020) 354 2020), conditions that may heighten uncertainty when guests encounter AI-enabled systems requesting personal information and thereby amplify privacy sensitivity. The findings therefore underscore the need for hotels operating in Albania to implement transparent, EU-aligned data-handling practices and to proactively communicate privacy safeguards, not only for compliance, but also as a practical mechanism for strengthening the trust that appears central to guest acceptance of AI-enabled services.

5.3. Perceived Value and Financial Acceptance

The results provide strong support for H5: respondents who identify more benefits and desire more smart features are significantly more likely to express both acceptance and willingness to pay. In terms of practical magnitude, the odds ratios from the full attitudinal models (

Table S6) indicate that each additional perceived benefit corresponds to approximately 15–20% higher odds of acceptance, while each additional desired feature increases odds by roughly 8–12%. These effect sizes, while modest at the individual unit level, become substantively meaningful when considering the observed ranges-guests at the upper end of benefit recognition (6–7 benefits) exhibit markedly higher acceptance probabilities than those identifying only one or two benefits. For practitioners, this suggests that expanding guests’ awareness of the multidimensional value proposition of AI-enabled services represents a viable strategy for enhancing both attitudinal and financial acceptance.

These findings confirm the foundational assumption of value-driven adoption central to TAM and UTAUT/UTAUT2 (Davis 1989; Venkatesh et al. 2012), though the operationalization employed here warrants theoretical reflection. Unlike traditional reflective scales measuring perceived usefulness as a unitary latent construct, the present study captured perceived value through formative “breadth indicators” counts of distinct benefits and features identified by each respondent. This approach conceptualizes perceived value as cumulative scope rather than unidimensional intensity: guests who identify more benefits perceive AI as useful across multiple functional domains (efficiency, personalization, convenience, sustainability) rather than intensely useful on a single dimension. This breadth-based operationalization may represent a complementary extension to standard TAM and UTAUT/UTAUT2 measures, capturing the multifaceted nature of value perceptions that single-item or narrow reflective scales may not fully represent. Future research could examine whether breadth and intensity of perceived use-fulness exert independent or interactive effects on technology acceptance.

The nonlinear analyses reported in

Section 4.6, though ultimately yielding modest improvements in model fit, revealed a marginally significant convex relationship between perceived benefits and willingness to pay (p ≈ 0.07). This pattern suggests potential threshold or accelerating effects: guests perceiving many benefits may exhibit disproportionately higher willingness to pay than those perceiving moderate benefits, as if accumulated value perceptions trigger a “tipping point” where hesitancy transforms into enthusiastic endorsement. Although linear models were retained for parsimony, this finding hints at nonlinear dynamics in value–acceptance relationships that merit further investigation, particularly in emerging markets where baseline value perceptions may cluster at lower levels, and interventions that shift guests across critical thresholds could yield outsized returns.

Regarding H6, privacy concerns reduce willingness to pay more strongly than they reduce general acceptance, as evidenced by larger effect sizes and consistent statistical significance in all models for the WTP outcome (OR ≈ 0.68, p < 0.01). This differential impact can be understood through several complementary theoretical lenses. Mental accounting theory (Thaler 1985) suggests that financial outlays trigger deliberate cost-benefit evaluations in which potential losses, including privacy risks, receive heightened cognitive scrutiny. Regulatory focus theory (Higgins 1997) posits that payment contexts may activate a prevention orientation (focused on avoiding negative outcomes) rather than a promotion orientation (focused on achieving positive outcomes), thereby amplifying sensitivity to threats such as data vulnerability. Additionally, research on the “pain of paying” indicates that monetary commitment activates loss-averse processing, rendering negative attributes more cognitively accessible and influential in decision-making (Prelec & Loewenstein 1998). Together, these frameworks suggest that the act of contemplating financial commitment fundamentally alters the psychological weighting of risks and benefits, explaining why privacy concerns that remain peripheral during general attitude formation become decisive when willingness to pay is at stake.

This distinction resonates with prior hospitality research demonstrating that willingness to pay for service innovations, whether green hotel features, smart room technologies, or experiential upgrades, is particularly sensitive to perceived risks and ethical evaluations (Kim & Han 2010; Kang et al. 2012; Hao et al. 2023). Guests appear to apply more stringent evaluative criteria when actual expenditure is involved, suggesting that the psychological processes governing WTP differ qualitatively from those shaping general acceptance. For AI-enabled hospitality services, this implies that value communication alone may be insufficient to secure price premiums; hotels must simultaneously address ethical concerns to convert positive attitudes into financial commitment.

It should be acknowledged that guests who identify more benefits or desire more features may differ systematically from others in unmeasured ways. Such individuals might possess higher technology readiness, greater innovativeness, or stronger general enthusiasm for novel experiences, dispositional factors that could partially account for the observed associations between perceived value and acceptance. While the models control for demographics, hotel-stay frequency, and prior AI experience, un-measured heterogeneity remains a potential confound that limits causal interpretation. The substantial variance in perceived benefits (SD = 1.39) and desired features (SD = 3.38) further underscores that guests are not homogeneous in their value perceptions, suggesting opportunities for market segmentation. Hotels might identify “value-sensitive” segments requiring extensive benefit communication and reassurance versus “tech-enthusiast” segments already primed to pay premiums with minimal persuasion. Tailored marketing strategies and tiered service offerings could capitalize on this heterogeneity.

These patterns underscore a crucial strategic insight for emerging markets such as Albania: the commercial viability of AI-enabled upgrades depends not only on functional value but also on guests’ ethical comfort, especially regarding data use. Several contextual factors amplify the importance of these findings. First, price sensitivity may be elevated in emerging economies, meaning that guests require more explicit and compelling justification for AI-related price premiums than might be necessary in wealthier markets. Second, the relatively modest average number of perceived benefits observed in this sample (M = 2.79 out of 7 possible) suggests the guests do not yet recognize the full value spectrum of AI-enabled services, representing both a challenge and an opportunity for targeted communication strategies that expand benefit awareness. Third, currency and income dynamics in Albania affect the practical interpretation of “willingness to pay more”; a price premium that appears modest in absolute euro terms may represent a significant relative expenditure for domestic travelers, heightening the evaluative scrutiny applied to such decisions. Collectively, these considerations suggest that hotels in Albania and comparable emerging markets must craft value propositions that are not only functionally compelling but also ethically transparent and economically justified relative to local purchasing power.

The results provide strong support for H5: respondents who identify more benefits and desire more smart features are significantly more likely to express both acceptance and willingness to pay, supporting value-based adoption mechanisms central to TAM (perceived usefulness) and UTAUT/UTAUT2 (performance expectancy and price value) (Davis 1989); Venkatesh et al. 2012).

Regarding H6, privacy concerns reduce willingness to pay more strongly than they reduce general acceptance, as evidenced by larger effect sizes and consistent statistical significance in all models for the WTP outcome. This distinction suggests that financial commitment heightens the salience of perceived privacy risk, consistent with evidence that privacy concerns and privacy assurances shape purchase-related responses in travel/hospitality digital contexts and that consumers may even pay price premiums for more privacy-protective options (Lee and Cranage 2011; Morosan & DeFranco 2015; Tsai et al. 2011).

These patterns underscore a crucial strategic insight for emerging markets such as Albania: the commercial viability of AI-enabled upgrades depends not only on functional value but also on guests’ ethical comfort, especially regarding data use.

5.4. Interpersonal, Cultural, and Moderation Effects

The findings provide partial support for H7, showing that lower digital familiarity, operationalized through limited awareness or experience, is associated with lower acceptance. While age differences emerged descriptively and in some models, the broad-er pattern indicates that digital exposure rather than age alone better explains the acceptance gradient.

Evidence for H8 is mixed. A preference for human interaction did not systematically reduce acceptance; in some models, it showed weak or borderline-positive effects. This ambiguity warrants deeper theoretical exploration. First, guests may simultaneously value human interaction and appreciate AI efficiency, these are not mutually exclusive preferences. The Paradoxes of Technology literature (Mick & Fournier 1998) suggests that consumers often hold contradictory attitudes toward technology, embracing its benefits while harboring reservations about its implications. Second, the importance of human interaction likely varies by service context: guests may strongly prefer human engagement for emotionally complex encounters (complaint resolution, personalized recommendations) while readily accepting AI for routine transactions (check-in, information requests). The global measure employed in this study may obscure such context-specific preferences. Third, framing effects may shape responses: whether AI is perceived as replacing or augmenting staff fundamentally alters evaluations, and the survey context may have primed respondents toward a complementary framing. Finally, the single Likert item capturing “importance of human interaction” may conflate distinct constructs preference for human warmth, discomfort with technology, need for service customization, that relate differently to AI acceptance. This measurement limitation suggests caution in interpreting the ambiguous findings and highlights the need for more differentiated assessment of interpersonal preferences in future research.

The weak effects observed may also reflect social desirability bias: guests might over-state the importance of human interaction in survey responses while behaviorally accepting AI-mediated services in practice. Alternatively, guests expressing strong preference for human interaction yet showing acceptance may represent a segment that compartmentalizes preferences, valuing human contact for some service elements while welcoming AI for others. These alternative explanations underscore the complexity of interpersonal expectations in technology-mediated hospitality encounters.

Support for H9 is modest but directionally consistent: better perceived cultural-linguistic fit correlates with higher acceptance, particularly in willingness to pay. This aligns with theories of cultural congruence in service encounters, indicating that guests evaluate AI technologies not only on functional performance but also on perceived alignment with local norms and communication styles (Holmqvist & Grönroos 2012; Holmqvist et al. 2014). However, it must be acknowledged that cultural-linguistic fit was operationalized through a single item, limiting interpretive confidence. Cultural congruence is inherently multidimensional, encompassing language adaptation, cultural idioms, communication style norms, humor conventions, and value alignment (Holmqvist et al. 2017; Paparoidamis et al. 2019). The global perception captured by the present measure cannot distinguish which specific dimensions of cultural fit matter most for AI acceptance. Future research employing multi-item scales or experimental manipulations of specific cultural adaptation features, such as language formality, greeting conventions, or locally relevant recommendations, could more precisely identify the mechanisms through which cultural fit shapes guest responses.

The Albanian context enriches interpretation of these cultural findings. Albanian hospitality traditions emphasize warmth, personal relationships, and guest honor, cultural values encapsulated in concepts such as “mikpritja” (the sacred duty of hospitality) that may heighten sensitivity to perceived impersonality in service encounters. Furthermore, Albania’s tourism sector serves diverse visitor segments, regional Balkan tourists, Western European travelers, and diaspora visitors returning to their homeland, each bringing distinct language preferences, cultural expectations, and familiarity with AI technologies. This heterogeneity complicates one-size-fits-all AI implementations and underscores the importance of culturally adaptive systems capable of adjusting interaction styles across guest segments. Additionally, post-communist legacies of institutional distrust in Albania may create unique dynamics: guests who harbor skepticism toward formal institutions may transfer such reservations to AI systems perceived as opaque or corporate-controlled, while simultaneously being receptive to technologies that enhance personal autonomy and reduce dependence on potentially unreliable human intermediaries. These culturally embedded factors likely shape acceptance in ways that differ from Western European contexts where most hospitality AI research has been conducted.

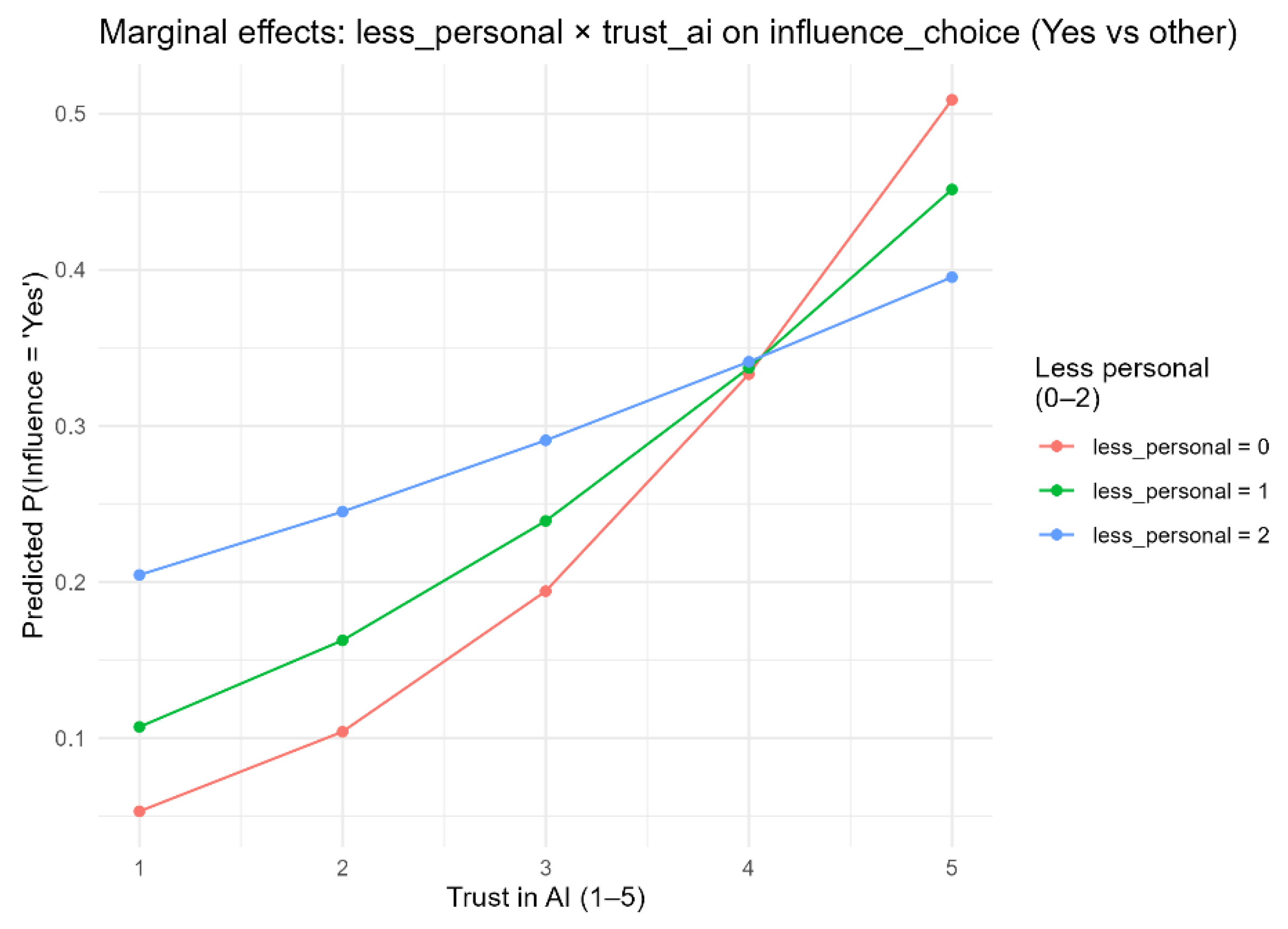

Consistent with H10, the interaction model provides evidence that trust moderates the negative influence of perceived loss of personal touch. The interaction coefficient from Model E1 (estimate ≈ −0.25, p ≈ 0.015;

Table S18) indicates a statistically significant moderation effect, with model fit improving modestly (pseudo-R

2 = 0.078 vs. 0.073 for the non-interaction specification). Examination of predicted probabilities (

Figure A1) reveals that when trust in AI is low (trust = 1), perceiving AI as impersonal actually increases endorsement of AI-driven hotel choice, from approximately 5% to 20% probability of selecting “Yes” as perceived impersonality increases from low to high. This counterintuitive pattern may reflect a desire for efficiency over warmth among low-trust guests: those who distrust AI’s data handling may nonetheless accept its functional utility precisely because they do not expect relational warmth from a system they regard skeptically. When trust is high (trust = 5), this relationship reverses: higher perceived impersonality corresponds to slightly reduced endorsement (from approximately 51% to 40% “Yes”), suggesting that highly trusting guests apply more holistic evaluative criteria that include interpersonal expectations.

This “trust compensation” mechanism can be understood through several established psychological frameworks. Halo effects (Nisbett & Wilson 1977) may lead high-trust guests to interpret AI attributes more charitably, perceiving impersonality as professional efficiency rather than relational deficiency. Cognitive consistency theory (Festinger 2001) suggests that guests experiencing high trust may minimize concerns about impersonality to maintain consonance between their positive AI attitudes and potential reservations about reduced warmth. The risk-as-feelings hypothesis (Loewenstein et al. 2001) offers a complementary explanation: trust may function as an affective heuristic that dampens the emotional weight of interpersonal concerns, enabling more favorable holistic evaluations. Finally, high-trust guests may have recalibrated their expectations, accepting that AI-mediated service involves inherent trade-offs between efficiency and warmth, and thus evaluate AI against different criteria than guests who remain skeptical.

These findings align with the broader literature on human-AI collaboration in service contexts (Huang & Rust 2018; Wirtz et al. 2018), which increasingly advocates an “augmentation” rather than “replacement” perspective. Guests appear to accept AI more readily when it is perceived as enhancing rather than substituting human capabilities, a framing consistent with the strong support for staff-AI collaboration observed in the descriptive results (M = 4.10 on a 5-point scale;

Table 6). The interaction findings extend this perspective by demonstrating that trust serves as a psychological mechanism enabling guests to reconcile efficiency benefits with interpersonal expectations, facilitating acceptance of AI within a complementary service model.

However, the interaction did not extend to willingness to pay, with the trust × personal touch term failing to reach significance (p ≈ 0.63). Several explanations may account for this null finding. Financial decisions may be governed more by cognitive cost-benefit calculations than by affective or relational considerations, rendering interpersonal trade-offs less influential once price enters the equation. As demonstrated in

Section 5.3, willingness to pay appears more directly determined by perceived functional value and privacy concerns, potentially leaving insufficient variance to be explained by interpersonal moderations. Additionally, guests willing to pay premiums may have already resolved interpersonal concerns during earlier attitudinal processing, creating a ceiling effect that attenuates moderation at the financial commitment stage. It should also be acknowledged that the non-significant interaction may reflect statistical power limitations: detecting interaction effects typically requires larger samples than main effects, and the present study may have been underpowered to identify moderation of the expected magnitude for the willingness-to-pay outcome. Future research with larger samples or experimental designs manipulating trust and impersonality independently could more definitively test whether this moderation operates differently across attitudinal and financial outcomes.

The possibility that a third variable drives the observed interaction cannot be entirely excluded. Guests high in technology readiness or dispositional openness to experience may simultaneously exhibit higher trust in AI and greater tolerance for impersonal service encounters, not because trust causally attenuates impersonality concerns, but because both orientations stem from a common underlying disposition. While the models control for multiple covariates, such unmeasured individual differences represent potential confounds that limit causal interpretation of the interaction.

These findings carry implications for service design in Albanian hotels and comparable emerging-market contexts. The trust-moderation finding suggests that hotels should prioritize trust-building initiatives, through transparency regarding data practices, visible security assurances, and demonstrations of AI reliability, before or alongside AI deployment. Establishing trust may preemptively buffer concerns about reduced personal touch, smoothing the acceptance pathway for guests who might otherwise resist technology perceived as impersonal. The importance of cultural-linguistic fit implies that AI interfaces in Albania should incorporate Albanian language options, culturally appropriate interaction styles (including appropriate formality gradients and greeting conventions), and local contextual knowledge (such as familiarity with Albanian destinations, customs, and service expectations). The ambiguous role of human interaction preferences suggests that hybrid service models, where AI handles routine, transactional interactions while human staff manage complex, emotional, or high-stakes encounters, may optimize acceptance across diverse guest segments. Such configurations honor guests’ interpersonal expectations while capturing the efficiency and consistency benefits that AI can provide, reflecting the complementary human-AI relationship that respondents in this study broadly endorsed.

5.5. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

To complement the quantitative models, the open-ended recommendation item (“Do you have any recommendations for hotels planning to integrate AI and smart technologies?”) was analyzed using a lightweight text-mining procedure. Of the 689 respondents, 228 provided written recommendations (33.1%). Responses ranged from single-word or short-phrase comments to longer statements (range 1–60 words; median ≈ 10 words; five responses contained ≥ 50 words). Response propensity did not differ meaningfully by gender or age group, suggesting limited evidence of systematic nonresponse along basic demographic lines; nevertheless, as with any optional open-ended item, some degree of self-selection toward more engaged participants cannot be ruled out.

Text preprocessing followed a transparent, reproducible pipeline (documented in the Supplementary R script): responses were lowercased, punctuation was removed, and common stop-words were excluded (English stop-words supplemented with a small set of Albanian function words). No stemming or lemmatization was applied, so morphologically related forms were retained as separate tokens. After preprocessing, the corpus contained 614 unique word types. Consistent with the survey focus, the most frequent terms were “ai” (85 occurrences), “hotels” (39 occurrences), “data” (32 occurrences), “staff” (27 occurrences), “guests” (27 occurrences), “human” (26 occurrences), and “smart” (26 occurrences), followed by “technology” (21 occurrences), “experience” (18 occurrences), “service” (16 occurrences), “privacy” (15 occurrences), and “personal” (11 occurrences). Notably, “data” and “privacy” emerged prominently despite not being explicitly prompted in the open-ended question, reinforcing the salience of information governance as a spontaneous concern. The co-occurrence of “privacy” (15 occurrences) with “security” (7 occurrences) and “transparency” (6 occurrences) further aligns with the quantitative evidence that ethical and data-handling considerations are central in respondents’ evaluations of AI-enabled hospitality services.

Bigram (two-word combination) analysis provided additional contextual structure, yielding 1,234 unique bigrams after preprocessing. The most frequent bigrams included “guest experience” (8 occurrences) and “human interaction” (8 occurrences), followed by “smart technologies” (7 occurrences) and “human touch” (6 occurrences). Several bigrams directly reflected implementation priorities and governance concerns, including “personal data” (5 occurrences), “integrate ai” (5 occurrences), and “data handling” (3 occurrences), as well as operational references such as “check ins” (4 occurrences) and “faster check” (3 occurrences). Importantly, a cluster of replacement-related bigrams: “replace human” (5 occurrences), “replace humans” (3 occurrences), “replace staff” (3 occurrences), and “replacing human” (2 occurrences), indicates that displacement concerns were raised voluntarily by respondents, even though job-loss anxiety was not a primary multi-item focus of the structured instrument. This is consistent with broader discussions in the hospitality automation literature that emphasize the importance of positioning AI as augmentative rather than substitutive (Ivanov & Webster 2019).

Taken together, the lexical patterns can be summarized as a set of recurring themes that map closely onto the study’s conceptual framing: (i) functional/operational value (e.g., faster or more convenient transactions), (ii) interpersonal experience (e.g., maintaining “human interaction” and “human touch”), (iii) privacy/data governance (e.g., “personal data,” “privacy,” “security,” “transparency,” “data handling”), and (iv) implementation and workforce readiness (e.g., “staff,” “training”). The latter is consistent with the strong endorsement of staff–AI collaboration observed in the structured item (mean ≈ 4.10 on a 5-point scale). A smaller subset of comments also referenced energy/sustainability (e.g., “energy” with mentions such as “energy management”), suggesting that environmental value propositions may be salient for some guests and could be explored more explicitly in future instrument refinements.

From a validity standpoint, the open-ended corpus provides convergent qualitative support for the quantitative results: privacy and data-handling language appears frequently and spontaneously, interpersonal warmth remains a salient reference point, and respondents often discuss implementation in terms of staff integration rather than full replacement. At the same time, the text-mining approach has clear limitations that should be acknowledged: frequency metrics capture lexical prominence but not sentiment, argument structure, or context; and without lemmatization, conceptually related word forms are distributed across separate tokens. Finally, because two-thirds of respondents did not provide textual recommendations, the qualitative results should be interpreted as complementary evidence rather than a fully representative distribution of views.

Practically, the phrasing used by respondents suggests actionable communication cues. The prominence of “human interaction” and “human touch” supports messaging that frames AI as enhancing service while preserving warmth. Similarly, frequent unprompted references to “personal data,” “privacy,” “security,” and “data handling” indicate that privacy communication should use accessible, guest-facing language rather than purely technical statements. The appearance of “gdpr” (2 occurrences) and “gdpr compliance” (1 occurrence) further suggests that explicit compliance-oriented reassurance may resonate with a subset of guests, particularly when framed as part of transparent data-governance practices.

5.6. Implications for Practice

The findings yield actionable implications for hospitality managers and technology designers, with particular relevance for Albania and comparable emerging tourism markets where guest-facing AI adoption remains nascent and expectations are evolving. To reduce over-interpretation and support implementation planning, the implications below are ordered by evidential strength: from model-consistent, robust effects to directionally suggested patterns, and each is framed with practical guidance and potential risks.

First, trust-building should be treated as the central strategic priority. Trust in AI was the most consistent attitudinal predictor across modelling frameworks; a one-unit increase in trust corresponded to approximately 40–50% higher odds of both acceptance and willingness to pay (OR ≈ 1.41–1.49;

Table S6,

Supplementary Materials). This places trust as a prerequisite for uptake, rather than a downstream consequence of adoption. In the Albanian context, trust-building is especially consequential because data-protection awareness and perceived safeguards vary across guest segments, and AI-enabled services often require some degree of personal-data handling. Regulatory messaging must also be accurate: Albania established a personal-data protection framework under Law No. 9887/2008 on Protection of Personal Data, and has more recently adopted Law No. 124/2024 , which aims to align national practice more closely with GDPR standards

(Regulation (EU) 2016/679

). Hotels should therefore communicate GDPR consistent practices in a way that is verifiable and aligned with operational reality. Operationally, trust-building requires visible practices rather than abstract assurances e.g., concise privacy notices at key touchpoints (booking page, check-in, Wi-Fi login), explicit opt-in consent for non-essential data uses, simple controls to disable personalization, and staff training so employees can explain data-handling practices clearly. A key risk is overpromising: if hotels claim transparency but cannot demonstrate consistent implementation (unclear retention rules, ambiguous vendor roles), perceived deception may erode trust more than silence would.

Second, privacy-sensitive design is particularly important when hotels seek price premiums. Privacy concerns reduced willingness to pay substantially (OR ≈ 0.68, p < 0.01) and the effect was stronger for WTP than for general acceptance. This implies that privacy protection is not merely a compliance issue but a revenue-relevant design constraint for premium, data-intensive features. For higher-end smart-room functions and personalization, hotels should implement safeguards that are both real and visible: guest-controlled data toggles; clear deletion options at checkout; transparent retention periods; and plain-language explanations of whether outputs are based on individual-level data or aggregated patterns. The qualitative prominence of “personal data,” “privacy,” and “data handling” indicates that governance concerns arise spontaneously; thus, guest-facing communication should use accessible language rather than technical jargon. An implementation risk is complexity: overly elaborate privacy interfaces can frustrate users or inadvertently imply excessive data collection. Privacy-by-default configurations, combined with optional personalization, reduce friction while preserving autonomy.

Third, experiential familiarity should be actively cultivated through low-risk onboarding. Prior experience with smart/AI-enabled hotels was a robust predictor (OR ≈ 1.46–1.53;

Table S6,

Supplementary Materials), consistent with the diffusion logic that trialability reduces perceived uncertainty. In lower-exposure markets, lowering the “risk of first use” may be one of the most efficient levers for improving acceptance. Hotels can operationalize this through brief demonstrations at check-in, QR-linked tutorials, staff-guided introductions for guests who opt in, and phased activation (basic functions first, advanced personalization later). Qualitative references to “guest experience,” comfort, and ease suggest that onboarding should prioritize clarity and reassurance rather than technological sophistication. Poor demonstrations can produce durable negative impressions; therefore, piloting with staff and a small set of guests before full rollout is advisable.

Fourth, AI should be framed and operationalized as augmentation rather than replacement of staff. Support for staff–AI collaboration was high (M = 4.10;

Table 6), while open-ended feedback contained replacement-related language, indicating that displacement concerns remain salient. Together, these patterns suggest that acceptance is higher when AI is positioned as supporting staff rather than substituting for human service labor. Messaging should therefore emphasize augmentation (e.g., “AI supports routine tasks so staff can focus on hospitality and problem-solving”) and preserve human service pathways for complex or emotionally sensitive interactions. Internal alignment is equally important: if employees interpret AI as surveillance or a precursor to workforce reduction, their skepticism may undermine guest trust. Involving frontline staff in implementation decisions, training, and escalation protocols can build ownership and improve service recovery when AI fails.

Fifth, cultural and linguistic localization appears to add incremental value, particularly for willingness to pay. Cultural–linguistic fit showed modest but directionally positive associations, suggesting that localized interfaces may improve perceived relevance and comfort across Albania’s mixed market (domestic guests, diaspora, regional visitors, and broader international tourism). Priorities include high-quality Albanian language support, appropriate formality and greeting conventions, and locally grounded recommendations. The risk is superficial adaptation: poor translations or culturally inappropriate suggestions may appear inauthentic and can damage trust. Localization should therefore involve local expertise and systematic testing with staff and guests prior to deployment.

Sixth, hotels should avoid one-size-fits-all implementations and instead offer differentiated pathways. The observed variability in perceived benefits, desired features, and attitudes implies that guest orientations are heterogeneous. A pragmatic segmentation for implementation can distinguish: (i) high-trust/high-exposure guests (most receptive to advanced features and potential premiums), (ii) cautious-but-open guests (best served by hybrid models with strong privacy assurances), and (iii) human-preference guests (best served by maintaining fully human pathways and introducing AI unobtrusively or behind-the-scenes). Segmentation can be operationalized via preference prompts (pre-arrival), opt-in behavior, and early-use patterns without requiring intrusive profiling.

Seventh, implementation priorities should be calibrated to property type and service context. Luxury properties may justify premium AI experiences if privacy assurances and service quality are high; budget properties may benefit more from operational efficiency tools than from guest-facing premium upgrades. Urban hotels may prioritize speed and information services, whereas resort properties may emphasize experience personalization. Independent properties may adopt phased approaches due to vendor and staffing constraints, while chains can standardize but must ensure local language and context fit.

Eighth, staff readiness is a core implementation condition rather than a downstream operational detail. Guest acceptance is partly mediated through staff behaviors; enthusiastic, competent staff support can facilitate uptake, while resistance can undermine even well-designed systems. Hotels should therefore implement basic change-management practices: clear internal communication about AI’s role, training that builds literacy (not only procedures), protocols for failures and service recovery, and scripts enabling staff to explain AI and data practices in guest-friendly language.

Ninth, a phased rollout with monitoring is advisable. A practical sequence is: (a) governance foundation (privacy notices, consent flows, vendor accountability, staff training), (b) low-risk optional guest-facing features (digital check-in, basic smart-room controls, simple recommendations while preserving human alternatives), (c) premium tier expansion for opt-in segments, and (d) optimization of the human–AI division of labor. Hotels should track KPIs aligned to the constructs in this study: trust indicators (perceived data safety, clarity of data practices), adoption indicators (usage and opt-in/opt-out rates), experience indicators (AI-specific feedback), financial indicators (premium uptake where offered), and staff indicators (comfort and training adequacy). Monitoring enables early detection of friction before it affects guest satisfaction and revenue.

Overall, successful AI implementation in Albanian hospitality is most likely when hotels prioritize trust-building and privacy protection, facilitate experiential familiarity, frame AI as augmenting human service, localize interfaces where relevant, differentiate offerings by guest segment and property context, invest in staff readiness, and continuously monitor outcomes. The evidence indicates that strategies integrating functional value with interpersonal and ethical safeguards are best positioned to convert positive attitudes into sustained use and, where feasible, financial premiums.

5.7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings and their practical implications.