Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background: Housing Retrofits as Complex Micro-Projects

2.1. The Concept of Complexity

- Unpredictability – outputs cannot be linearly derived from inputs.

- Non-linearity – small changes can produce disproportionate effects.

- Emergence – challenges and requirements shift over time [13].

2.2. Static and Dynamic Complexity

2.3. Complexity in Housing Retrofit Projects

2.4. Complexity, Delivery, and CO2 Outcomes

2.5. Research Gap and Contribution

- An interdisciplinary lens was adopted to link engineering and social theory to assess sustainable thermal retrofit policy [27]. They highlight neglected issues such as health, affordability, and heritage.

- A systematic review of “green retrofitting” was conducted to identify critical success factors (CSFs) and barriers, including unreliable technologies and material shortages [28].

- Chinese policies promoting building green retrofit were examined, and they identified barriers related to finance, awareness, and technical capacity [29].

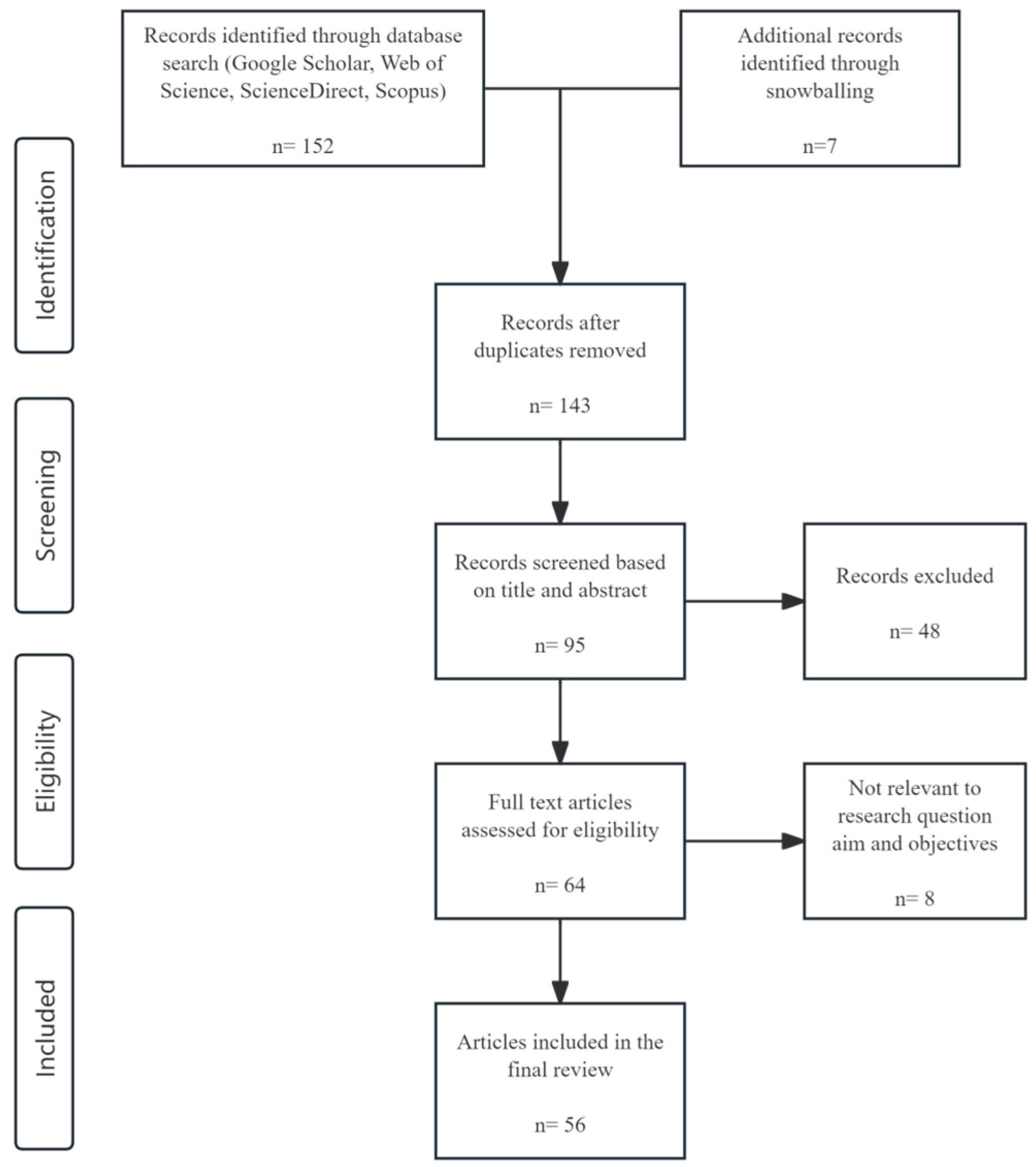

3. Methods: Integrative Review with PRISMA-Style Transparency

3.1. Rationale for the Integrative Review

3.2. Review Protocol

3.3. Search Strategy

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- addressed housing retrofit projects with explicit discussion of management, organisation, or delivery.

- provided empirical or conceptual insights relevant to the Owner, Supplier, or Delivery domains.

- were published in peer-reviewed journals or as authoritative reports between 2005 and 2022.

- were written in English and focused on housing (not commercial or industrial buildings).

- We excluded studies that:

- focused solely on technical or engineering aspects without organisational or management analysis.

- addressed new-build projects rather than retrofit.

- were purely policy commentaries without methodological transparency.

3.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

- bibliographic information (title, author, year, journal, DOI).

- research focus and methods.

- housing type and country context.

- key findings on barriers, drivers, and delivery processes.

- Owner Domain – including owner-occupiers, social landlords, and private landlords.

- Supplier Domain – covering manufacturers, merchants, contractors, and installers.

- Delivery Domain – focusing on project execution and integration.

3.6. Iterative Thematic Synthesis

3.7. Synthesis and Interpretation

- recurring barriers and drivers across domains.

- cross-domain interdependencies shaping project outcomes.

- implications for energy and potential CO2 performance.

4. Results: Evidence Across the Three Domains

4.1. Overview of the Evidence Base

4.2. Owner Domain

4.2.1. Owner-Occupiers

4.2.2. Social Landlords

4.2.3. Private Landlords

4.3. Supplier Domain

4.3.1. Intermediary Role and Market Maturity

4.3.2. Knowledge and Capability Gaps

4.3.3. Conservatism and Resistance

4.3.4. Supplier–Owner Relationship

4.4. Delivery Domain

4.4.1. Uncertainty and Risk

4.4.2. Occupant Interactions

4.4.3. Performance Verification

4.4.4. Managerial Capabilities

4.5. Key insights Across Domains

4.6. Summary of Common Challenges

- Fragmented project management – retrofits lack integrated delivery models linking design, installation, and verification.

- Trust and communication deficits – low confidence between owners and suppliers undermines uptake and satisfaction.

- Performance uncertainty – the energy performance gap remains pervasive due to dynamic complexity.

- Socio-technical misalignment – technical measures often conflict with occupant preferences or use patterns.

4.7. Implications for Carbon Outcomes and Delivery Practice

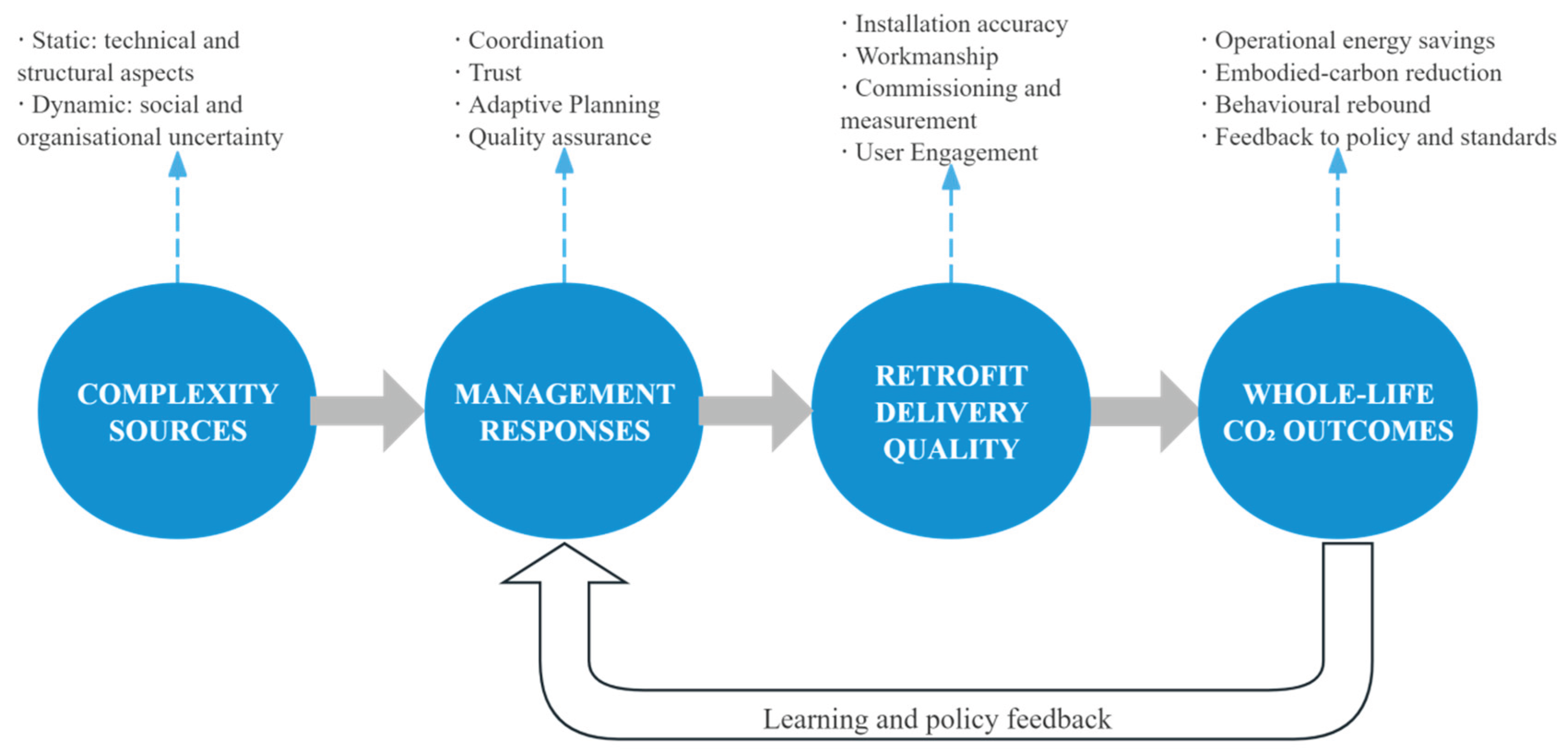

5. Framework and Discussion: Mapping Complexity, Delivery, and Whole-Life CO2

5.1. Linking Project Complexity to CO2 Performance

5.2. The three-Domain Interaction Model

6. Implications and Future Research

6.1. Managerial and Policy Implications

- Adopt complexity-aware management practices.

- 2.

- Strengthen quality assurance and verification.

- 3.

- Professionalise the micro-enterprise supply chain.

- 4.

- Encourage owner engagement and trust.

- 5.

- Integrate retrofit policy with carbon accounting.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Research Agenda

- Quantification of management-carbon linkages.

- 2.

- Comparative analysis across regions.

- 3.

- Integration with digital technologies.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions. Our World in Data. 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- CPC. Homes Fit for the Future: Project Position Report. Connected Places Catapult: London. 2019. Available online: https://cp-catapult.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2022/05/Homes-for-the-future-Project-position-paper.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- HMG. The energy white paper: Powering our net zero future. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: London. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5fdc61e2d3bf7f3a3bdc8cbf/201216_BEIS_EWP_Command_Paper_Accessible.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- CCC. UK housing: Fit for the future? Committee for Climate Change: London. 2019. Available online: https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/UK-housing-Fit-for-the-future-CCC-2019.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Killip, G.; Owen, A.; Topouzi, M. Exploring the practices and roles of UK construction manufacturers and merchants in relation to Housing Energy Retrofit. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 251, 119205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.M. Three domains of Project Organising. International Journal of Project Management 2014, 32, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.M.; Maytorena, E.; Sergeeva, N. Strategic project organizing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baccarini, D. The concept of Project Complexity—a review. International Journal of Project Management 1996, 14, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, S.A.; Mostashari, A. 5.2.2 complexity measures to predict system development project outcomes. INCOSE International Symposium 2013, 23, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, T.R. Complexity. Research Handbook on Complex Project Organizing 2023, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The sciences of the artificial; The MIT Press: Cambridge, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making. Harvard Business Review 2007, 1, 8–13. Available online: https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making (accessed on 02 May 2025).

- Bakhshi, J.; Ireland, V.; Gorod, A. Clarifying the project complexity construct: Past, present and future. International Journal of Project Management 2016, 34, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldi, J.; Maylor, H.; Williams, T. Now, let’s make it really complex (complicated). International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2011, 31, 966–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, T.; Davies, A. Managing structural and dynamic complexity: A tale of two projects. Project Management Journal 2014, 45, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, P.A.; Daniel, C. Complexity, uncertainty and mental models: From a paradigm of regulation to a paradigm of emergence in project management. International Journal of Project Management 2018, 36, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, P.A.; Daniel, E. Multi-level project organizing: A Complex Adaptive Systems Perspective. Research Handbook on Complex Project Organizing 2023, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- de Boeck, L.; Verbeke, S.; Audenaert, A.; De Mesmaeker, L. Improving the energy performance of residential buildings: A literature review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 52, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, J.R.S. Complexity in project management. Procedia Computer Science 2017, 121, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killip, G. Products, practices and processes: Exploring the innovation potential for low-carbon housing refurbishment among small and medium-sized enterprises (smes) in the UK construction industry. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.; Mitchell, G.; Gouldson, A. Unseen influence—the role of Low Carbon Retrofit Advisers and installers in the adoption and use of Domestic Energy Technology. Energy Policy 2014, 73, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettifor, H.; Wilson, C.; Chryssochoidis, G. The appeal of the green deal: Empirical evidence for the influence of energy efficiency policy on renovating homeowners. Energy Policy 2015, 79, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murto, P.; Jalas, M.; Juntunen, J.; Hyysalo, S. Devices and strategies: An analysis of managing complexity in Energy Retrofit Projects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 114, 109294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjørring, L.; Gausset, Q. Drivers for retrofit: A sociocultural approach to houses and inhabitants. Building Research & Information 2019, 47, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, A.; McCarthy, L. Taming the “masculine pioneers”? changing attitudes towards energy efficiency amongst private landlords and tenants in New Zealand: A case study of dunedin. Energy Policy 2019, 126, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunikka-Blank, M.; Galvin, R. Introducing the prebound effect: The gap between performance and actual energy consumption. Building Research & Information 2012, 40, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R.; Sunikka-Blank, M. Ten questions concerning sustainable domestic thermal retrofit policy research. Building and Environment 2017, 118, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagarajan, R.; Abdullah Mohd Asmoni, M.N.; Mohammed, A.H.; Jaafar, M.N.; Lee Yim Mei, J.; Baba, M. Green retrofitting – a review of current status, implementations and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 67, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, X.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, G. Building Green Retrofit in China: Policies, barriers and recommendations. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Breslin, D.; Callahan, J.L.; Iszatt-White, M. Advancing literature review methodology through rigour, generativity, scope and transparency. International Journal of Management Reviews 2022, 24, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; van Knippenberg, D. Creating high-impact literature reviews: An argument for ‘integrative reviews. Journal of Management Studies 2020, 57, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Manning, J.; Denyer, D. 11 evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. Academy of Management Annals 2008, 2, 475–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, G.; Shannon, S.; Cummings, M.; Leavey, G. An updated systematic review of interventions to increase awareness of mental health and well-being in athletes, coaches, officials and parents. Systematic Reviews 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, S.; Hosseini, M.R.; Kocaturk, T.; Weiss, M.; Barnett, M. The product-service system approach for housing in a circular economy: An integrative literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 403, 136845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, R.A.; Söderholm, A. A theory of the temporary organization. Scandinavian Journal of Management 1995, 11, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risholt, B.; Berker, T. Success for energy efficient renovation of dwellings—learning from private homeowners. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R. Making the ‘rebound effect’ more useful for performance evaluation of thermal retrofits of existing homes: Defining the ‘energy savings deficit’ and the ‘energy performance gap. Energy and Buildings 2014, 69, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusk, K.; Kalamees, T. Retrofit cost-effectiveness: Estonian apartment buildings. Building Research & Information 2015, 44, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Lamond, J.; Proverbs, D.G.; Sharman, L.; Heller, A.; Manion, J. Technical considerations in green roof retrofit for stormwater attenuation in the central business district. Structural Survey 2015, 33, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, M.; Carlsson, V. What you see is not what you get: Single-family house renovation and energy retrofit seen through the lens of sociomateriality. Construction Management and Economics 2016, 35, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.; Curtis, J. An examination of the abandonment of applications for energy efficiency retrofit grants in Ireland. Energy Policy 2017, 100, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauvain, J.; Karvonen, A. Social housing providers as unlikely low-carbon innovators. Energy and Buildings 2018, 177, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, A.; Roberts, T.; Walker, I. Consumer engagement in low-carbon home energy in the United Kingdom: Implications for future energy system decentralization. Energy Research & Social Science 2018, 44, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matosović, M.; Tomšić, Ž. Evaluating homeowners’ retrofit choices – croatian case study. Energy and Buildings 2018, 171, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, G. The determinants of energy efficient retrofit investments in the English residential sector. Energy Policy 2018, 120, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Pettifor, H.; Chryssochoidis, G. Quantitative modelling of why and how homeowners decide to renovate energy efficiently. Applied Energy 2018, 212, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Pardalis, G.; Mahapatra, K.; Mainali, B. Physical vs. aesthetic renovations: Learning from Swedish House owners. Buildings 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yu, T.; Hong, J.; Shen, G.Q. Making incentive policies more effective: An agent-based model for energy-efficiency retrofit in China. Energy Policy 2019, 126, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broers, W.M.H.; Vasseur, V.; Kemp, R.; Abujidi, N.; Vroon, Z.A.E.P. Decided or divided? an empirical analysis of the decision-making process of Dutch homeowners for energy renovation measures. Energy Research & Social Science 2019, 58, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Yu, L.; Wang, L.; Tao, J. Integrating willingness analysis into investment prediction model for large scale building energy saving retrofit: Using fuzzy multiple attribute decision making method with Monte Carlo Simulation. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 44, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, B.; Jones, R.V.; Fuertes, A. Opportunities and barriers to business engagement in the UK domestic retrofit sector: An industry perspective. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology 2020, 42, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Qian, Q.K.; Meijer, F.; Visscher, H. Exploring key risks of energy retrofit of residential buildings in China with transaction cost considerations. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 293, 126099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcarate-Aguerre, J.F.; Conci, M.; Zils, M.; Hopkinson, P.; Klein, T. Building Energy Retrofit-as-a-service: A total value of ownership assessment methodology to support whole life-cycle building circularity and decarbonisation. Construction Management and Economics 2022, 40, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, L.; Hajdukiewicz, M.; Seri, F.; Keane, M.M. A novel BIM-based process workflow for building retrofit. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 50, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, M.; Temeljotov-Salaj, A.; Lindkvist, C.M.; Støre-Valen, M. Sustainable building renovation in residential buildings: Barriers and potential motivations in Norwegian culture. Construction Management and Economics 2022, 40, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wilde, M. The Sustainable Housing Question: On the role of interpersonal, impersonal and professional trust in low-carbon retrofit decisions by homeowners. Energy Research & Social Science 2019, 51, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, W.; Ruddock, L.; Smith, L. Low carbon retrofit: Attitudes and readiness within the social housing sector. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2013, 20, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Bryde, D.J. A field-level examination of the adoption of sustainable procurement in the social housing sector. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2015, 35, 982–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandclément, C.; Karvonen, A.; Guy, S. Negotiating comfort in low energy housing: The Politics of Intermediation. Energy Policy 2015, 84, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.S.; Causone, F.; Cunha, S.; Pina, A.; Erba, S. Addressing the challenges of public housing retrofits. Energy Procedia 2017, 134, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.; Wolff, A. Energy efficiency retrofits in the residential sector – analysing tenants’ cost burden in a German field study. Energy Policy 2018, 122, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mitchell, A.; Lemon, M.; Mazhar, M.U.; Ooms, W.; van Heerde, R. The transition of Dutch social housing corporations to sustainable business models for new buildings and retrofits. Energies 2021, 14, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ástmarsson, B.; Jensen, P.A.; Maslesa, E. Sustainable renovation of residential buildings and the landlord/tenant dilemma. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Tommelein, I.D.; Ballard, G. Target-setting practice for loans for commercial energy-retrofit projects. Journal of Management in Engineering 2015, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- März, S. Beyond economics—understanding the decision-making of German small private landlords in terms of energy efficiency investment. Energy Efficiency 2018, 11, 1721–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miu, L.; Hawkes, A.D. Private landlords and energy efficiency: Evidence for policymakers from a large-scale study in the United Kingdom. Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, P.A.; Schwarz, P.M.; Wu, J.S. Fee credits as an economic incentive for green infrastructure retrofits in stormwater-impaired urban watersheds. Journal of Sustainable Water in the Built Environment 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghorn, G.H.; Syal, M.G.M. Risk framework for energy performance contracting building retrofits. Journal of Green Building 2016, 11, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, F.; Hitchings, R.; Shipworth, M. Understanding the missing middlemen of domestic heating: Installers as a community of professional practice in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science 2016, 19, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.; Gleeson, C.; Winch, C. What kind of expertise is needed for low energy construction? Construction Management and Economics 2016, 35, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrovatin, N.; Zorić, J. Determinants of energy-efficient home retrofits in Slovenia: The role of information sources. Energy and Buildings 2018, 180, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, F.; Murtagh, N.; Hitchings, R. Managing professional jurisdiction and domestic energy use. Building Research & Information 2018, 46, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallesen, T.; Jacobsen, P.H. Articulation work from the middle—a study of how technicians mediate users and Technology. New Technology, Work and Employment 2018, 33, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murto, P.; Jalas, M.; Juntunen, J.; Hyysalo, S. The difficult process of adopting a comprehensive energy retrofit in housing companies: Barriers posed by nascent markets and complicated calculability. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.; Janda, K.B.; Owen, A. Preparing ‘middle actors’ to deliver zero-carbon building transitions. Buildings and Cities 2020, 1, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, N.; Owen, A.M.; Simpson, K. What motivates building repair-maintenance practitioners to include or avoid energy efficiency measures? evidence from three studies in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 73, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.; Murtagh, N.; Owen, A. Domestic retrofit: Understanding capabilities of micro-enterprise building practitioners. Buildings and Cities 2021, 2, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaunbrecher, B.S.; Arning, K.; Halbey, J.; Ziefle, M. Intermediaries as gatekeepers and their role in retrofit decisions of house owners. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 74, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryde, D.J.; Schulmeister, R. Applying lean principles to a building refurbishment project: Experiences of key stakeholders. Construction Management and Economics 2012, 30, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovers, R. New Energy Retrofit Concept: ‘renovation trains’ for mass housing. Building Research & Information 2014, 42, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Zou, P.X.W.; Stewart, R.A.; Bertone, E.; Sahin, O.; Buntine, C.; Marshall, C. Government championed strategies to overcome the barriers to public building energy efficiency retrofit projects. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 44, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Chiu, L.F. Innovation in deep housing retrofit in the United Kingdom: The role of situated creativity in transforming practice. Energy Research & Social Science 2020, 63, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, F.; Morgan, E.; Greer, K.; Wade, J.; Killip, G. Domestic Retrofit Supply Chain Initiatives and Business Innovations: An international review. Buildings and Cities 2021, 2, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, R.; Löwstedt, M.; Räisänen, C. Working in a loosely coupled system: Exploring practices and implications of coupling work on construction sites. Construction Management and Economics 2020, 39, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, J.A.; Ajayi, S.O. Understanding the impediments to sustainable structural retrofit of existing buildings in the UK. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 60, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wilde, M.; Spaargaren, G. Designing trust: How strategic intermediaries choreograph homeowners’ low-carbon retrofit experience. Building Research & Information 2018, 47, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapiou, A.; Flanagan, R.; Norman, G.; Notman, D. The changing role of builders merchants in the construction supply chain. Construction Management and Economics 1998, 16, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbu, C.O. Perceived degree of difficulty of management tasks in construction refurbishment work. Building Research & Information 1995, 23, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbu, C.O. Skills, knowledge and competencies for managing construction refurbishment works. Construction Management and Economics 1999, 17, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S. How buildings learn: What happens after they’re built; Viking: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eunomia. Building Skills for Net Zero. Construction Industry Training Board: Peterborough, 2021. Available online: https://eunomia.eco/reports/building-skills-for-net-zero/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Jones, P.; Lannon, S.; Patterson, J. Retrofitting existing housing: How far, how much? Building Research & Information 2013, 41, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.M.; Brunet, M.; Cao, D. Research Handbook on Complex Project Organizing: Edited by Graham Winch, Maude Brunet and Dongping Cao; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, 2023.

| Complicatedness (Static Complexity) | Complexity (Dynamic Complexity) |

|---|---|

| Tangible, countable, predictable elements of a project | Unpredictable, nonlinear, interdependent relationships |

| Challenges known; outcomes generally predictable with expertise | Uncertain interactions lead to unforeseen outcomes |

| Managed by detailed planning and control | Managed by adaptability, learning, and communication |

| Example: constructing a standard house | Example: retrofitting occupied dwellings with variable needs |

| Database | Fields searched | Core Keywords and Boolean Strings | Time Horizon | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Scopus | Title and Abstract | “housing retrofit” OR “energy renovation” OR “building refurbishment” OR “residential retrofit”) AND (“project management” OR “construction management” OR “delivery” OR “supply chain” OR “stakeholder”) | 2005–2022 | English |

| Domains | Reference | Number of Articles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner Domain | Owner-occupier | Tjørring and Gausset(2019) [24]; Ambrose & McCarthy(2019) [25]; Sunikka-Blank & Galvin(2012) [26]; Liu et al. (2020) [29]; Risholt and Berker(2013) [38]; Galvin(2014) [39]; Kuusk & Kalamees (2015) [40]; Wilkinson et al.(2015) [41]; Buser & Carlsson(2017) [42]; Collins & Curtis (2017) [43]; Cauvain & Karvonen(2018) [44]; Hope et al.(2018) [45]; Matosović & Tomšić (2018) [46]; Trotta (2018) [47]; Wilson et al.(2018) [48]; Bravo et al.(2019) [49]; Liang et al.(2019) [50]; Broers et al.(2019) [51]; Zheng et al.(2019) [52]; Butt et al.(2020) [53]; Jia et al.(2021) [54]; Azcarate-Aguerre et al.(2022) [55]; D'Angelo et al.(2022) [56]; Jowkar et al.(2022) [57]; de Wilde(2019) [58]; | 25 |

| Social landlord | Cauvain & Karvonen (2018) [44]; Trotta (2018) [47]; Swan et al. (2013) [59]; Meehan & Bryde (2015) [60]; Grandclément et al. (2015) [61]; Monteiro et al. (2017) [62]; Weber & Wolff (2018) [63]; Lambrechts et al. (2021) [64]. | 8 | |

| Private landlord | Trotta (2018) [47]; Weber & Wolff (2018) [63]; Ástmarsson et al. (2013) [65]; Lee et al. (2015) [66]; März (2018) [67]; Miu & Hawkes (2020) [68]; Malinowski et al. (2020) [69]. | 7 | |

| Supplier Domain | Killip et al. (2020) [5]; Owen et al. (2014) [21]; Berghorn & Syal (2016) [70]; Wade et al. (2016) [71]; Clarke et al. (2017) [72]; Hrovatin & Zorić (2018) [73]; Wade et al. (2018) [74]; Pallesen and Jacobsen (2018) [75]; Murto et al. (2019) [76]; Simpson et al. (2020) [77]; Murtagh et al. (2021) [78]; Simpson et al. (2021) [79]; Zaunbrecher et al. (2021) [80]. | 13 | |

| Delivery Domain | Killip (2013) [20]; Owen et al. (2014) [21]; Bryde and Schulmeister (2012) [81]; Rovers (2014) [82]; Alam et al. (2019) [83]; Lowe and Chiu (2020) [84]; Brocklehurst et al. (2021) [85]; Sandberg et al. (2021) [86]; Dauda & Ajayi (2022) [87]. | 9 | |

| Domain | Core Complexity Drivers | Mechanisms Affecting CO2 Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Owner | Decision uncertainty; aesthetic vs. energy priorities; limited knowledge; trust deficits | Determines project scope and retrofit depth; behavioural rebound reduces realised savings |

| Supplier | Predominantly small and micro-enterprises with limited integration across the supply chain; weak training systems; conservative, risk-averse practices | Affects installation quality, commissioning accuracy, and the durability of CO2 benefits |

| Delivery | On-site uncertainty, occupant interaction, and poor project management practices | Shapes actual energy savings through workmanship, sequencing, and verification |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).