Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Existing Test Methods and the Importance of Aspect Ratio

1.2. Effect of Aspect Ratio on Compressed Earth Blocks

1.3. Effect of Aspect Ratio on Compressed Earth Cylinders

1.4. Knowledge Gap

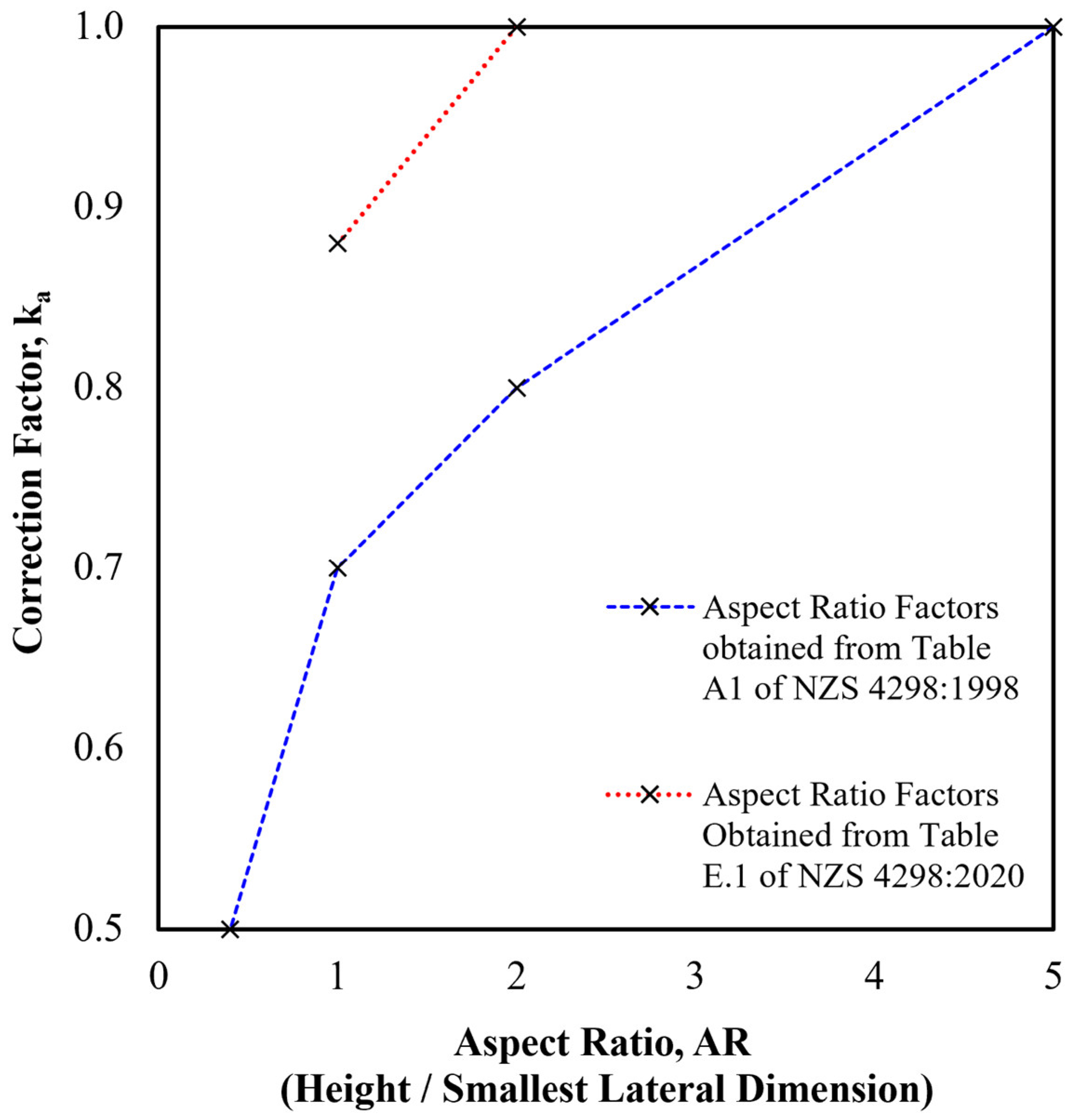

- Current aspect ratio correction factors published within NZS 4298:2020 [31] only address aspect ratios ranging from 1.0 – 2.0, which does not account for the majority of compressed earth blocks documented in the existing literature, which appear to be between 0.5 – 0.9.

- Unlike other building materials, there are no aspect ratio correction factors for un-stabilised or fibre-reinforced compressed earth cylinders.

- Blocks and cylinders have been used in the existing literature to assess the mechanical properties of compressed earth composites. However, the relationship between blocks and cylinders remains ambiguous.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Classification of Materials

2.1.1. Soil Properties

2.1.2. Fibre Properties

2.2. Manufacture of Test Specimens

2.2.1. Mix Design

2.2.2. Production Methodology

2.2.3. Sample Drying

2.3. Destructive Testing

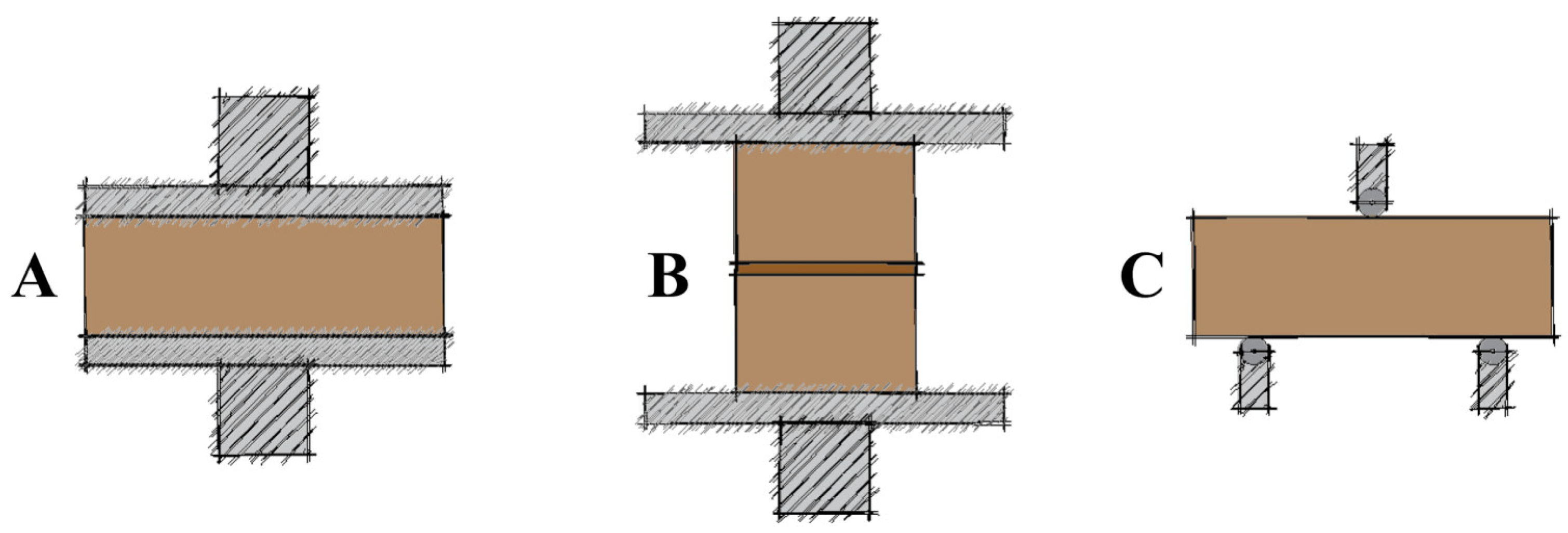

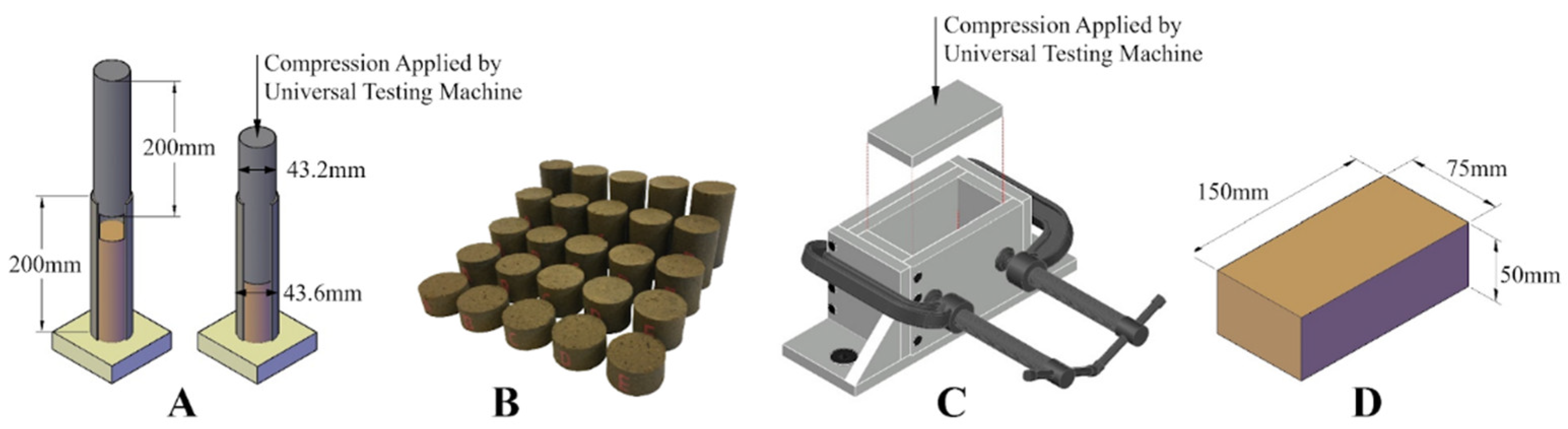

2.3.1. Compression Test of Compressed Earth Cylinders

2.3.2. Compression Test of Compressed Earth Blocks

2.4. Numerical Modelling

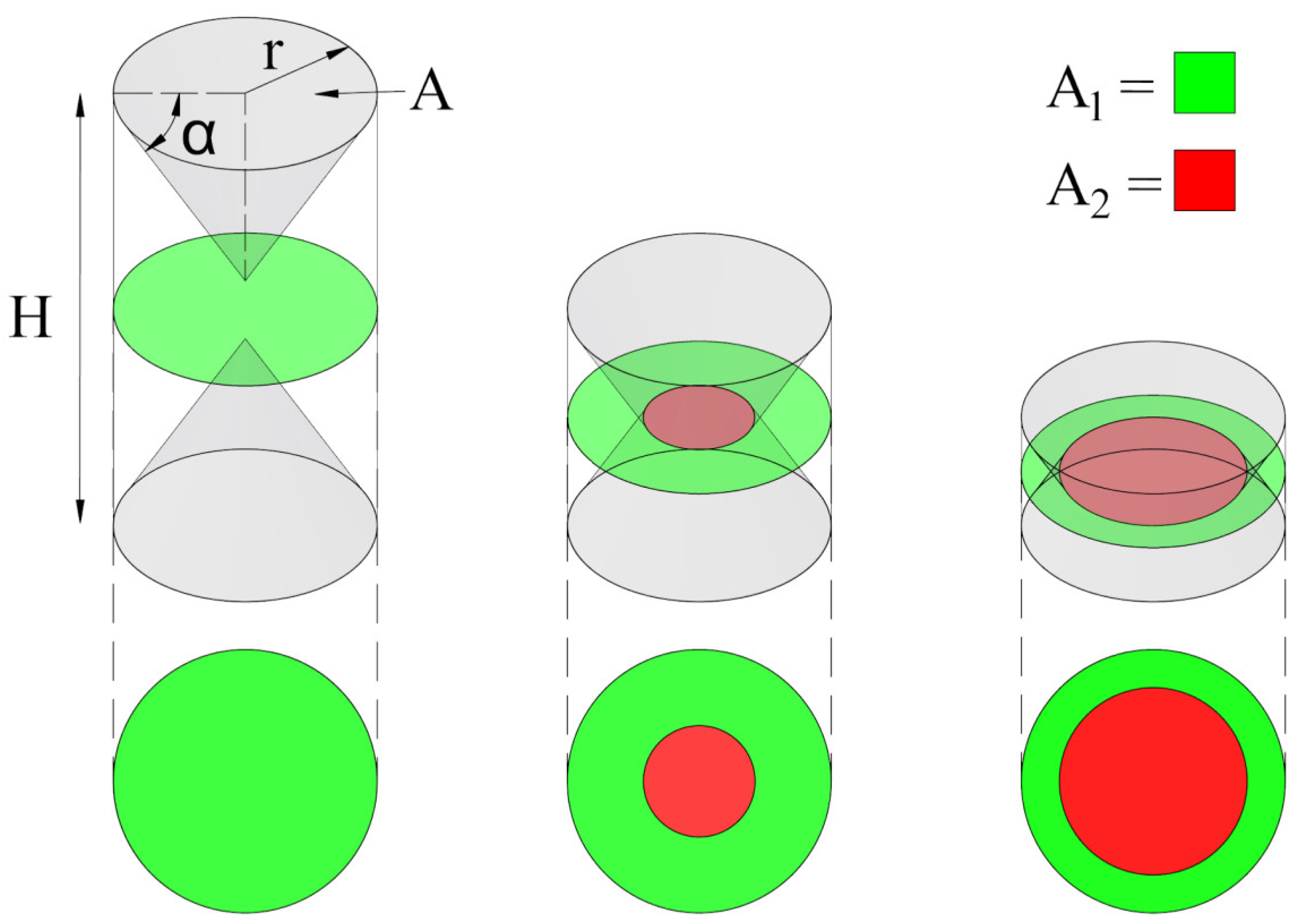

2.5. Hypothesis of Intersecting Cones

| , | (2) | |

|

, |

(2.1) | |

| , | (2.2) | |

| , | (2.3) | |

| , | (2.4) | |

|

, (2.5) NOTE: |

(2.5) | |

| where: | ||

| = Unconfined Compressive Stress (MPa) | ||

| k = | Coefficient of Confinement, where: | |

| • BE & SS: k = 6.5 | ||

| • FRBE & FRSS: k = 12.0 | ||

| A = | Surface Area, (mm2) | |

| H = | Height of Cylinder (mm) | |

| r = | Radius of Cylinder (mm) | |

| α = | Angle of the Failure Plane (o), where: | |

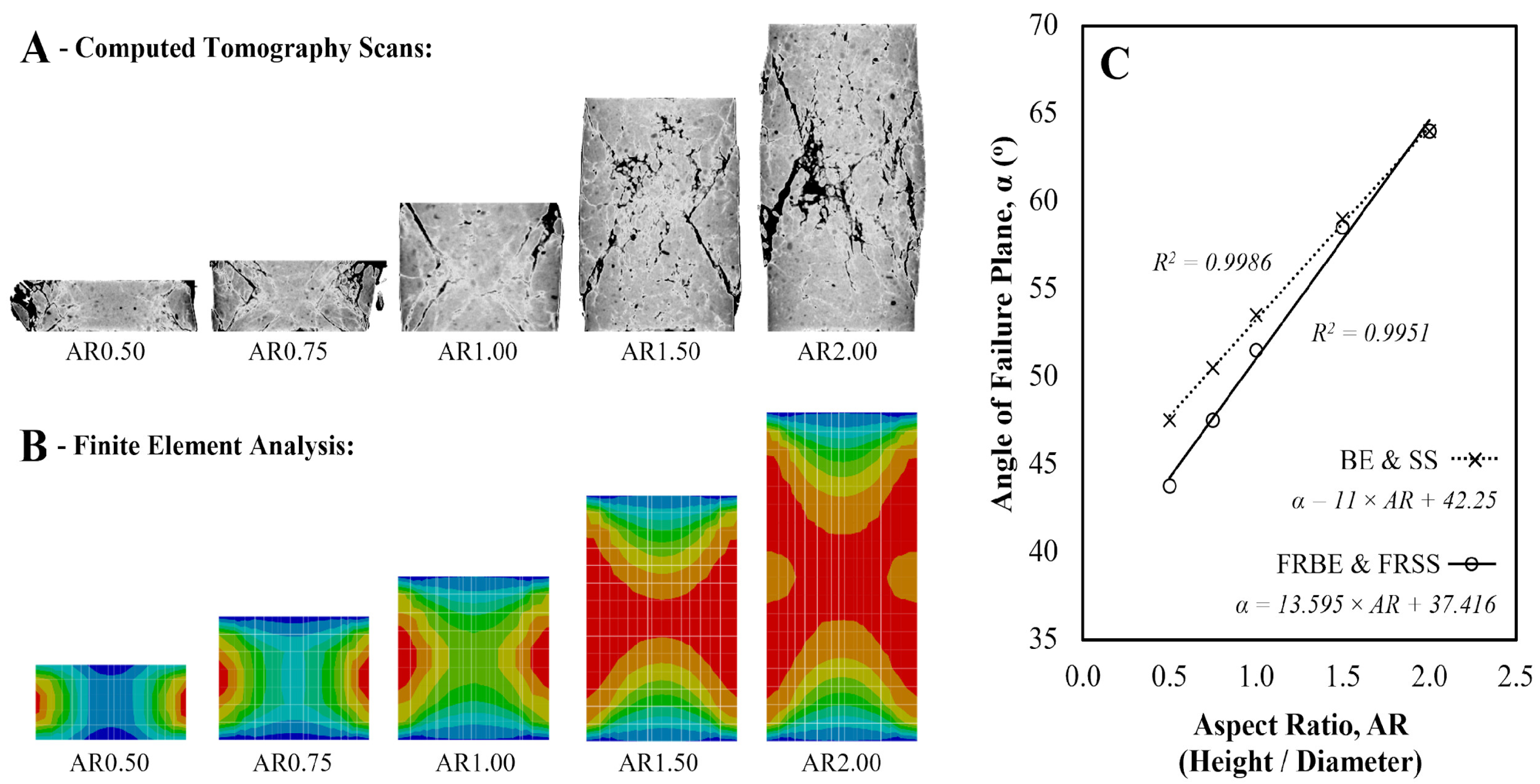

| • BE & SS: α = 11 × AR + 42.25 (See Figure 10C for Derivation) | ||

| • FRBE & FRSS: α = 13.595 × AR + 37.416 (See Figure 10C for Derivation) | ||

| AR = | Aspect Ratio (Height / Diameter) of a Cylindrical Specimen | |

3. Results

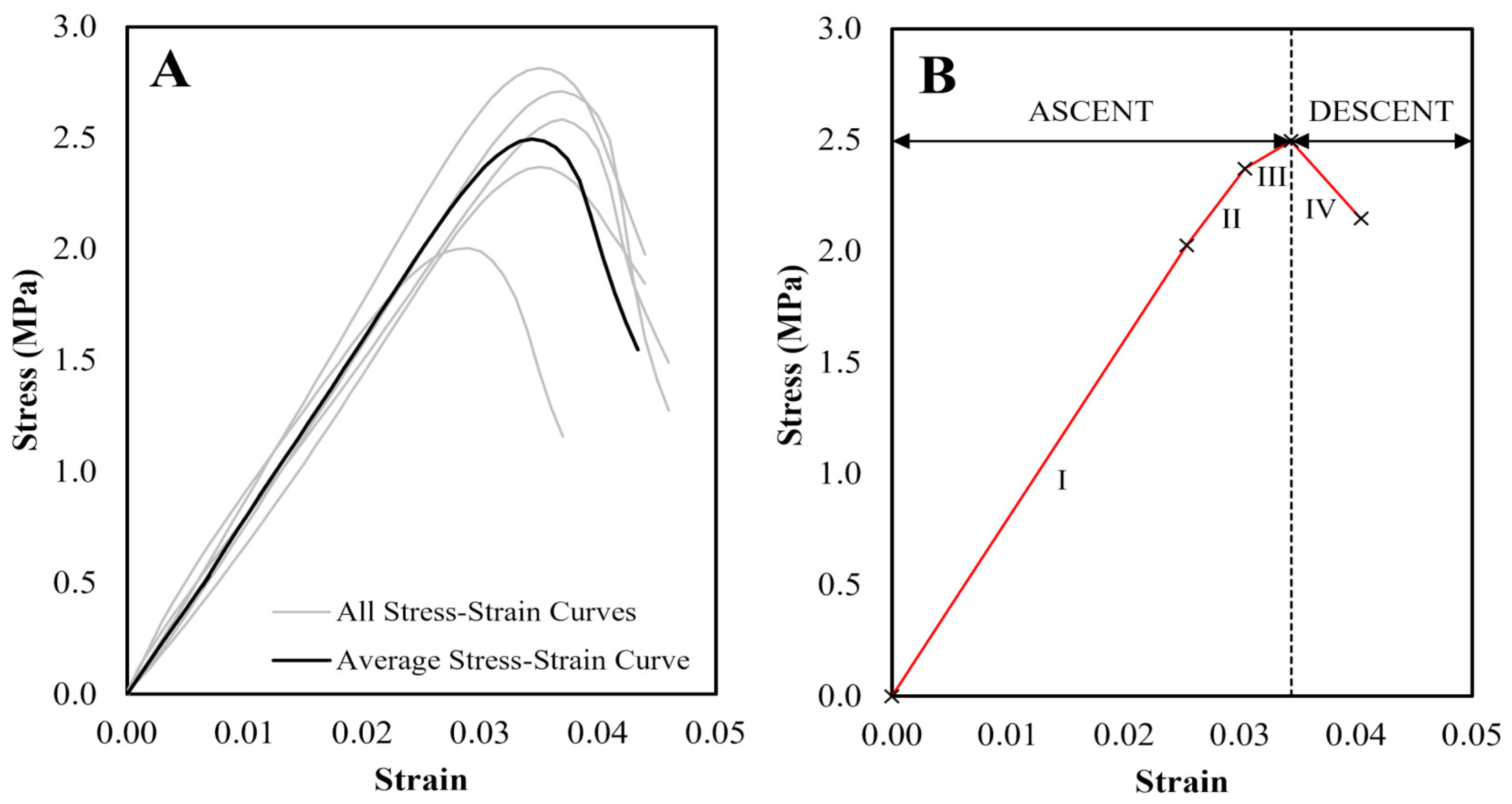

3.1. Compressed Earth Cylinders

3.1.1. Properties of Compressed Earth Cylinders

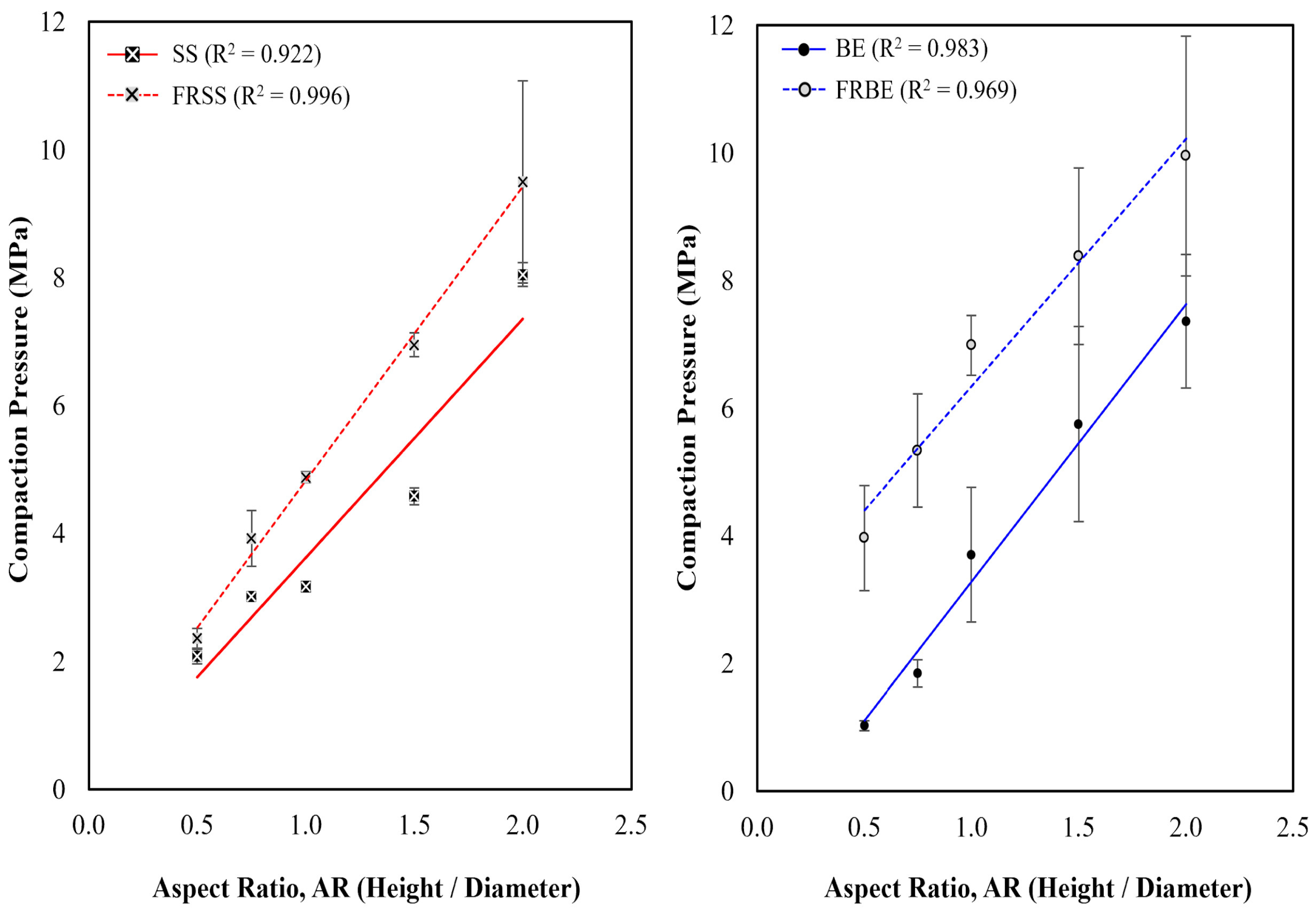

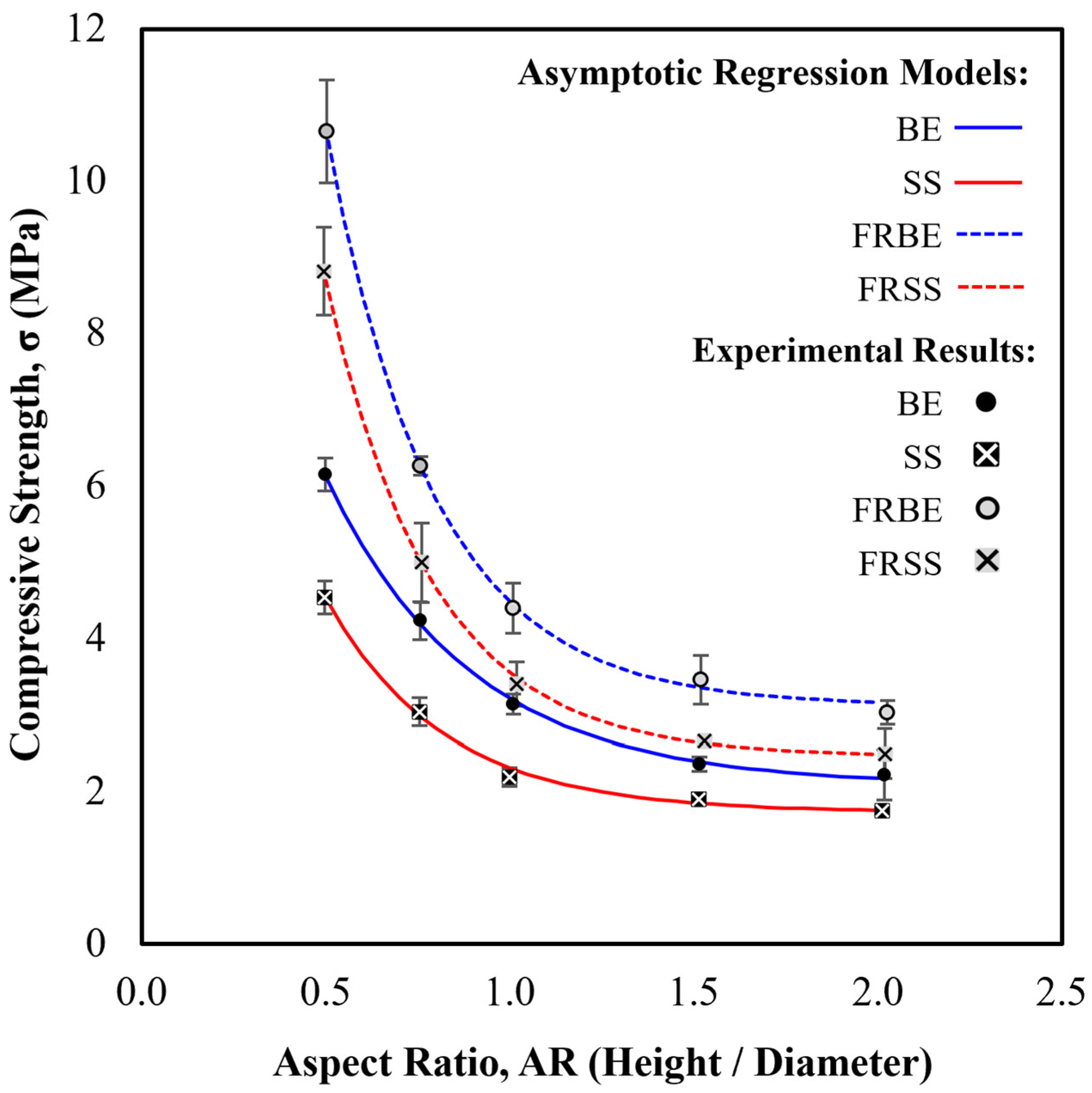

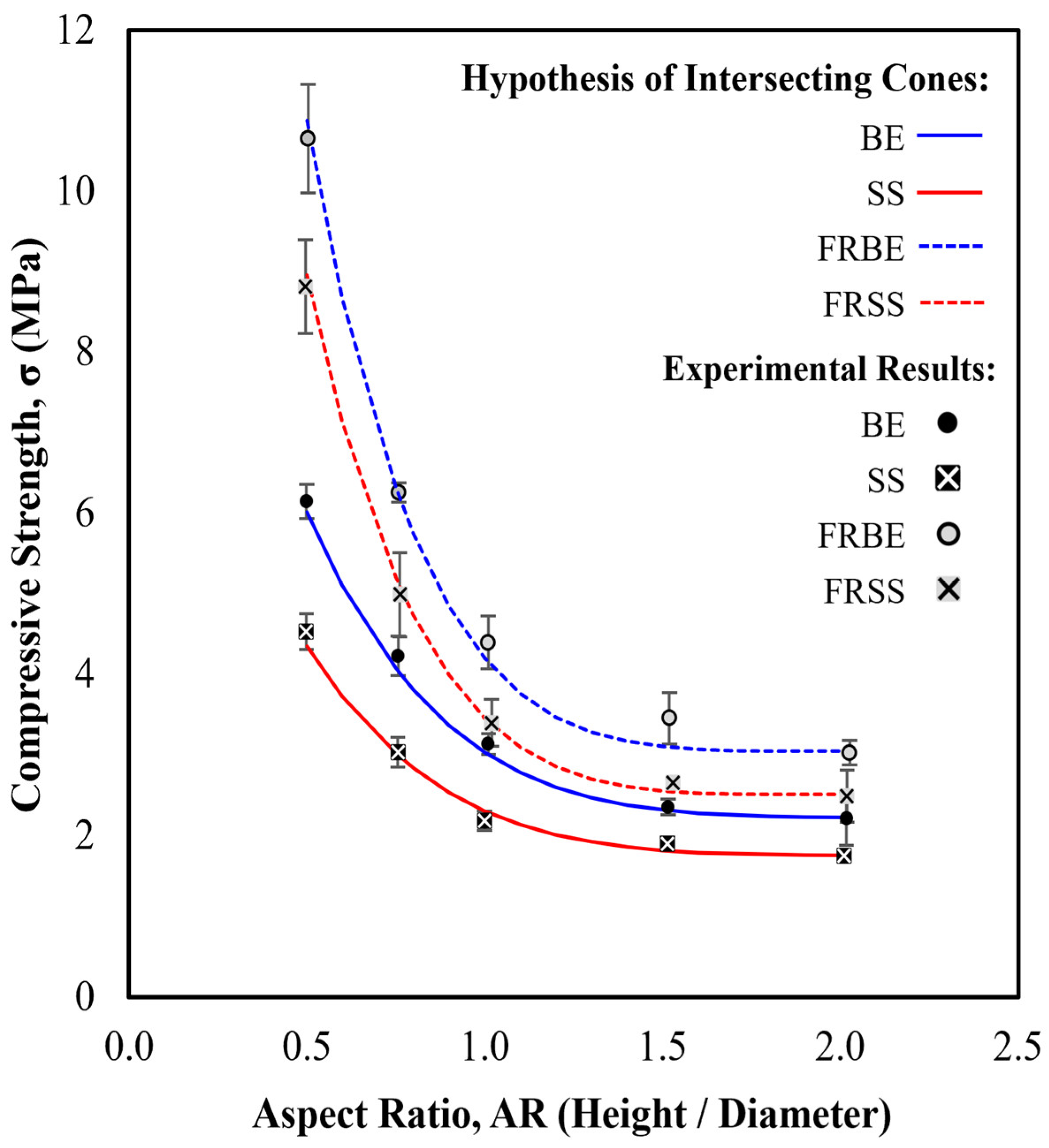

3.1.2. Aspect Ratio vs Compressive Strength

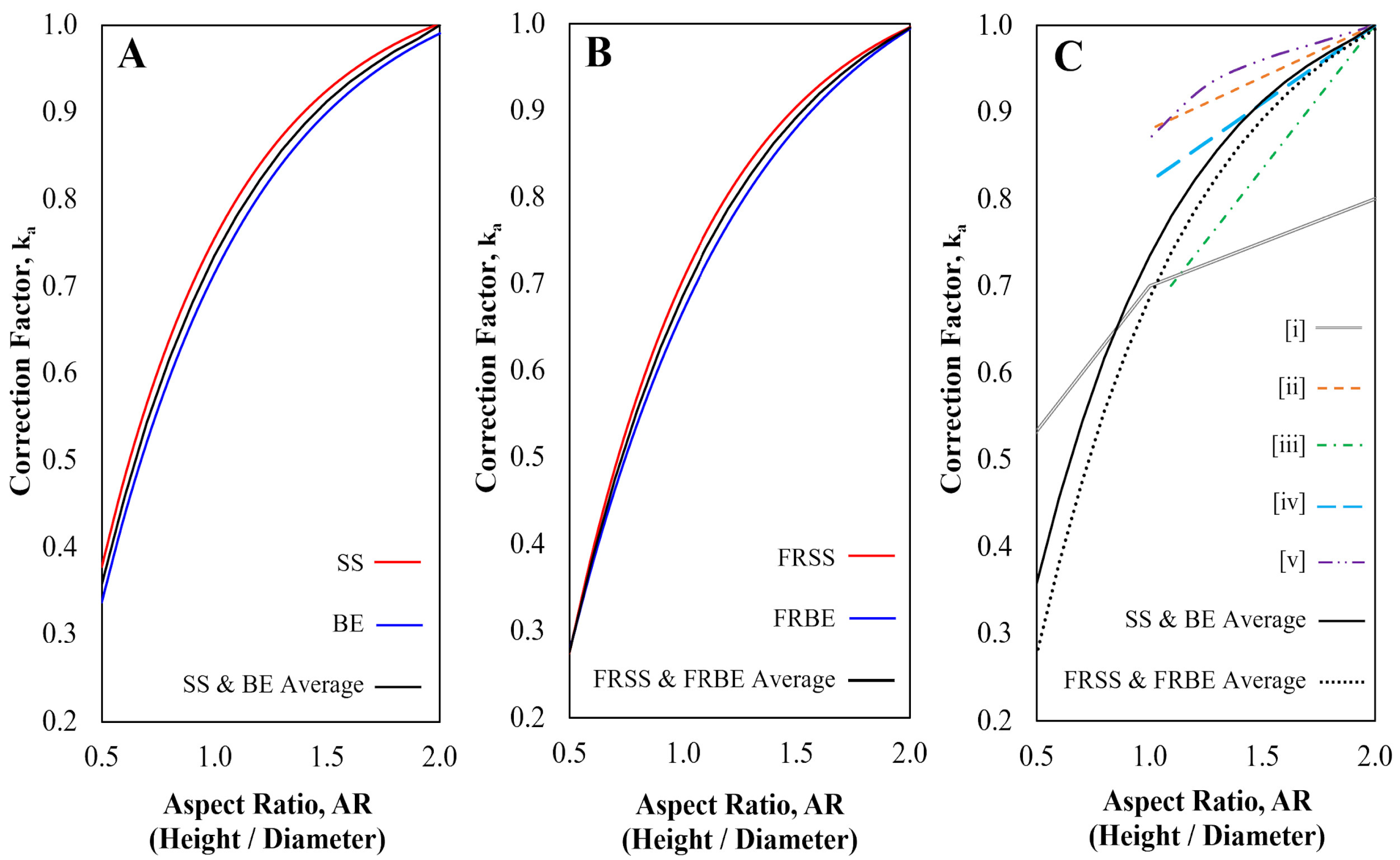

3.1.3. Aspect Ratio Correction Factors

3.2. Compressed Earth Blocks

3.2.1. Properties of Compressed Earth Blocks

4. Conclusions

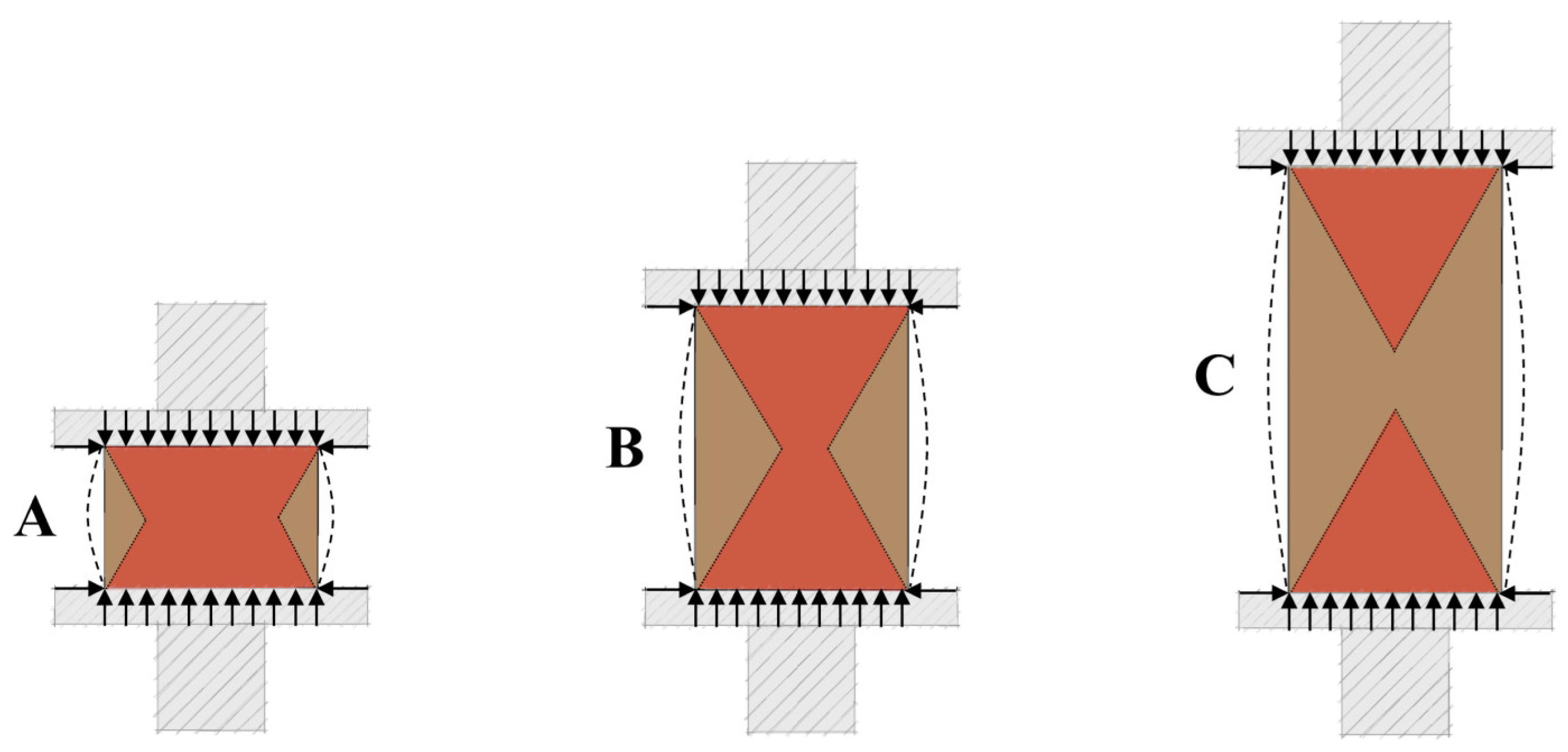

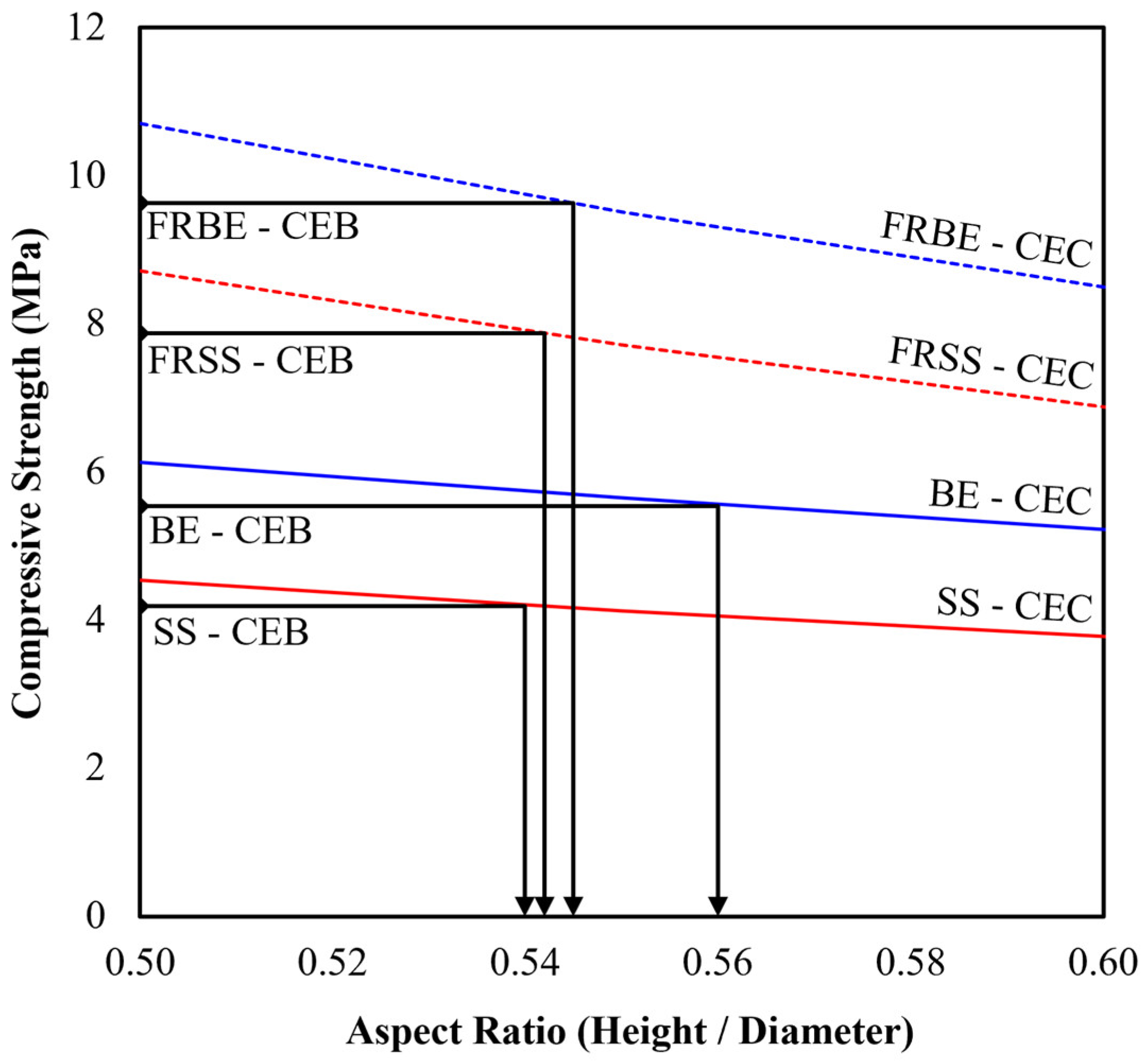

- Specimens with a lower aspect ratio displayed higher compressive strength due to confinement caused by platen restraint. The addition of jute fibre reinforcement was found to increase the apparent compressive strength at each aspect ratio. In samples with a low aspect ratio, the effects of confinement caused by platen restraint are compounded by the influence of fibre reinforcement, resulting in a disproportionately large increase in apparent compressive strength.

- Novel aspect ratio correction factors are derived from the experimental data to enable the conversion between the Unconfined Compressive Strength (UCS) and Apparent Compressive Strength (ACS) of un-stabilised and fibre-reinforced CECs. This directly supports standard structural design practices by providing the true material strength necessary for the capacity calculation. Further, statistical analysis suggests that soil type may not significantly influence aspect ratio correction factors. However, the addition of fibre reinforcement was found to statistically influence the aspect ratio correction factors of samples with low aspect ratios (0.50, 0.75 and 1.00).

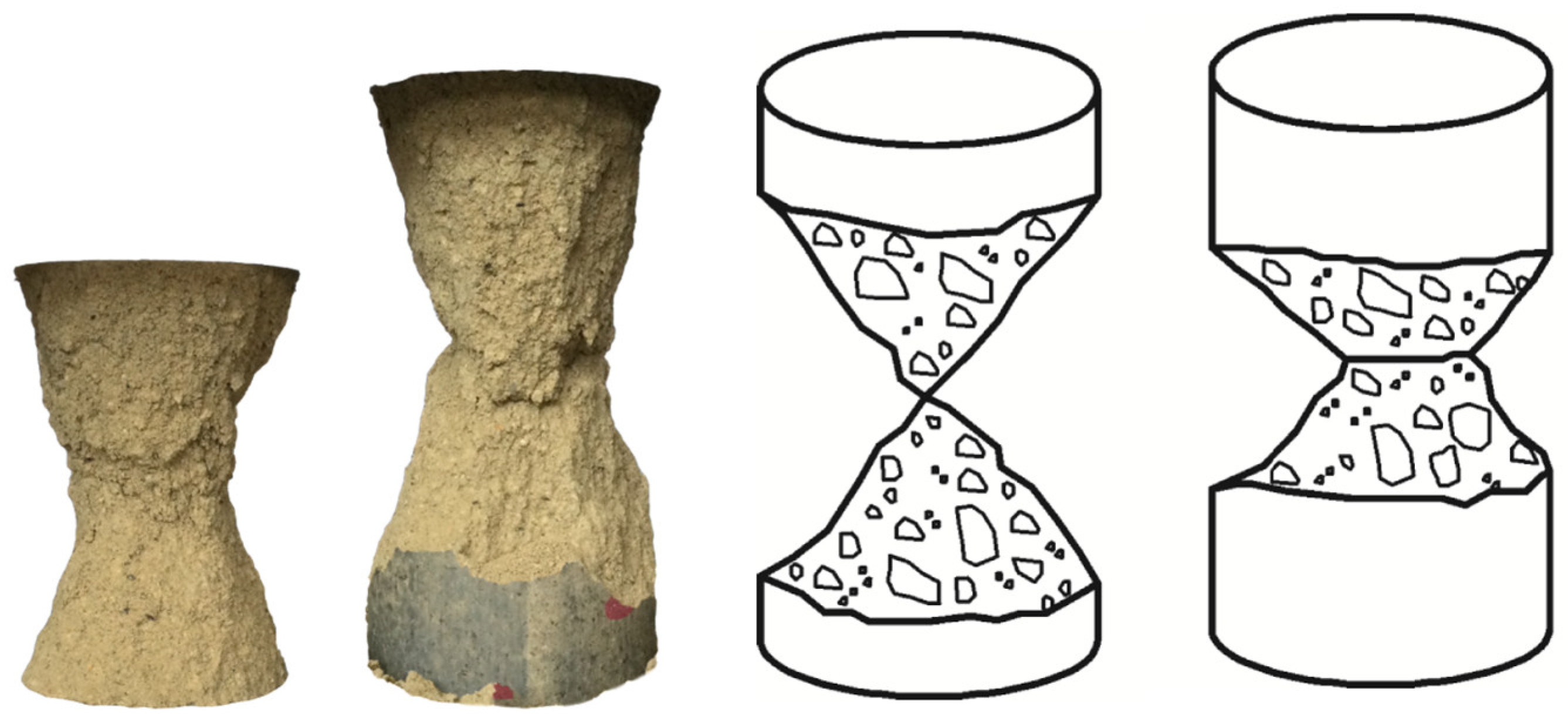

- Computed Tomography (CT) scans were performed to visualise the fibre distribution and internal crack formations following compression testing. The observations suggest that the aspect ratio and the addition of fibre reinforcement (an independent variable in the statistical analysis) may influence the internal crack formation and the angle at which the shear failure plane is developed, influencing the ACS of the material.

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA) was successfully used to model Compressed Earth Cylinders at different aspect ratios to examine the internal stress concentrations. Frictional contact between the test specimen and platens of the test machine was modelled using a frictional coefficient of 0.2, which was found to accurately replicate the influence of platen restraint.

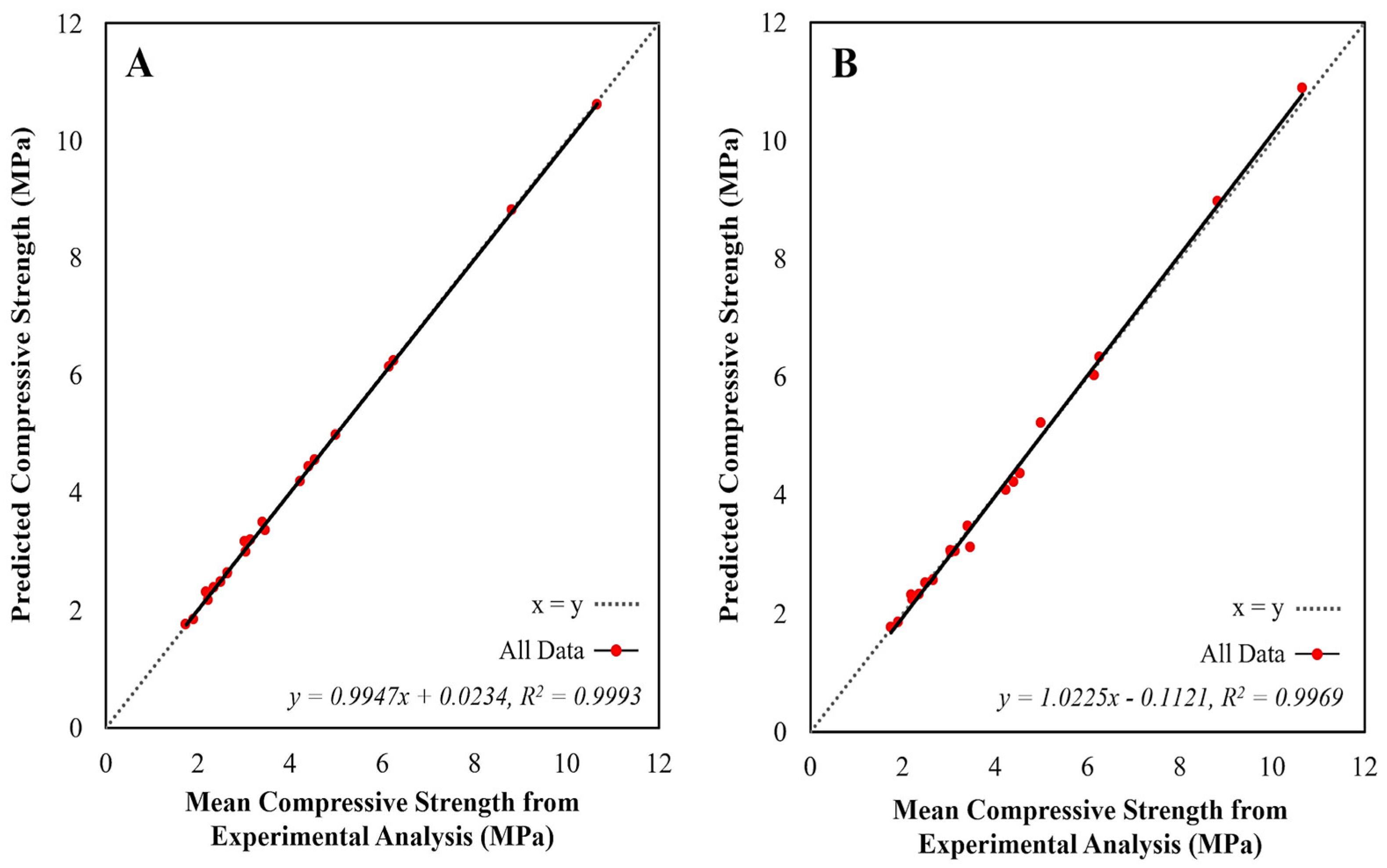

- A novel method for calculating the Apparent Compressive Strength (ACS) of CECs with an aspect ratio ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 is presented, utilising an original hypothesis of intersecting cones. The predicted values demonstrate a strong correlation with the experimental results, which validates the proposed hypothesis as a viable method, but is a slightly lesser predictor than the asymptotic model.

- The relationship between CECs and CEBs was assessed, and a conversion factor of 0.861 was determined. This conversion factor enabled the CECs to predict the ACS of CEBs with an accuracy of 2.7 %. The conversion factor was applicable to each mix design, which suggests that, for the two soil types investigated, the conversion factor is insensitive to the difference between the soil types or the presence of fibre reinforcement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Aubert, J.-E.; Faria, P.; Maillard, P.; Ouedraogo, K.A.J.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Prud’homme, E.; et al. Characterization of Earth Used in Earth Construction Materials. In Testing and Characterisation of Earth-Based Building Materials and Elements; Fabbri, A., Morel, J.-C., Aubert, J.-E., Bui, Q.-B., Gallipoli, D., Reddy, B.V.V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 17–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, J.; Ongwen, N.; Ogam, E.; Auma, M.; Fellah, Z.E.A.; Mageto, M.; Ben Mansour, M.; Oduor, A. Acoustical properties of compressed earth blocks: Effect of compaction pressure, water hyacinth ash and lime. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, J.A.; Ali, M. Influence of Aspect Ratio on the Properties of Compressed Earth Cylinders and Compressed Earth Blocks. In 5th International Conference on Bio-Based Building Materials; Springer Science and Business Media B.V., 2023; pp. 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, J.A.; Ali, M.; Tatari, A.; Martinson, D.B. Effects of Fibre Moisture Content on the Mechanical Properties of Jute Reinforced Compressed Earth Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Chao, S.S. Influences of Specimen Geometry and Loading Rate on Compressive Strength of Unstabilized Compacted Earth Block. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5034256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, D.; Varum, H.; Costa, A. Influence of the testing procedures in the mechanical characterization of adobe bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, K.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Barbosa, N.P. Behaviour of composite soil reinforced with natural fibres. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1999, 21, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Esna-ashari, M. Effect of waste tire cord reinforcement on unconfined compressive strength of lime stabilized clayey soil under freeze-thaw condition. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 82, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.W.; Gallipoli, D.; Perlot, C.; Mendes, J. Mechanical behaviour of hypercompacted earth for building construction. Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, T.; Ramos, L.F.; Lourenço, P.B. Characterization of dry-stack interlocking compressed earth blocks. Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 2015, 48, 3059–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardari, M.A.; Lakho, N.A.; Amur, M.A. Structural behaviour of large size compressed earth blocks stabilized with jute fiber. J. Eng. Res. (Kuwait) 2020, 8, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkanthi, S.N.; Balthazaar, N.; Perera, A.A.D.A.J. Lime stabilization for compressed stabilized earth blocks with reduced clay and silt. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 12, e00326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, C.; Paula Junior, A.C.; Teixeira, E.R.; Mateus, R. Optimisation of Compressed Earth Blocks (CEBs) using natural origin materials: A systematic literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiki, G.; Nshimiyimana, P.; Kouchadé, C.; Messan, A.; Houngan, A.; André, P. Physico–mechanical and durability performances of compressed earth blocks incorporating quackgrass straw: An alternative to fired clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 133064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahbabi, S.; Bouferra, R.; Saadi, L.; Khalil, A. Evaluation of the void index method on the mechanical and thermal properties of compressed earth blocks stabilized with bentonite clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Islam, M.S.; Hossain, M.I. Suitability of Vetiver straw fibers in improving the engineering characteristics of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 134224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogas, J.A.; Real, S.; Cruz, R.; Azevedo, B. Mechanical performance and shrinkage of compressed earth blocks stabilised with thermoactivated recycled cement. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Islam, M.S.; Elahi, T.E. Potential of waste rice husk ash and cement in making compressed stabilized earth blocks: Strength, durability and life cycle assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.C.; Pkla, A.; Walker, P. Compressive strength testing of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, J.E.; Maillard, P.; Morel, J.C.; Al Rafii, M. Towards a simple compressive strength test for earth bricks? Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 2016, 49, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.V.V.; Morel, J.-C.; Faria, P.; Fontana, P.; Oliveira, D.V.; Serclerat, I.; Walker, P.; Maillard, P. Codes and Standards on Earth Construction. In Testing and Characterisation of Earth-Based Building Materials and Elements; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Mesbah, A.; El Gharbi, Z.; Morel, J.C. Mode opératoire pour la réalisation d’essais de résistance sur blocs de terre comprimée. Mater. Struct. 1997, 30, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.; Pkla, A. A model to measure compressive strength of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2002, 16, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, J.A.; Ali, M.; Etienne, G. Utilisation of construction, demolition and excavation waste for the production of compressed trommel fines blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 134985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, H.; Guillaud, H. Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide, 1st ed.; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, B.V.V. Compressed Earth Block and Rammed Earth Structures, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigassi, V. Compressed Earth Blocks: Manual of Production; Deutsches Zentrum für Entwicklungstechnologien; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaud, H.; Joffroy, T.; Odul, P. Compressed Earth Blocks- Manual of Design and Construction: Volume II; Deutsches Zentrum für Entwicklungstechnologien; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.J. Strength and erosion characteristics of earth blocks and earth block masonry. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2004, 16, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, J.A.; Ali, M.; Tatari, A.; Martinson, D.B. An investigation into the influence of geometry on compressed earth building blocks using finite element analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards New Zealand. NZS 4298:2020; Materials and Construction for Earth Buildings. 2020.

- Morel, J.C.; Pkla, A.; Walker, P. Compressive strength testing of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, K.A.; Jankulovski, E. Aspect Ratio Correction Factors for Soilcrete Blocks. In Transactions of the Institution of Engineers, Australia; 1992; pp. 309–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Mukhopadhyay, T.; Waseem, S.A.; Singh, B.; Iqbal, M.A. Effect of Platen Restraint on Stress–Strain Behavior of Concrete Under Uniaxial Compression: a Comparative Study. Strength Mater. 2016, 48, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 4th ed.; Pearson: Essex, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, M.R.A.; Van Mier, J.G.M. Experimental investigation of concrete fracture under uniaxial compression. Mech. Cohesive-Frict. Mater. 1996, 1, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, M.V.V.; La Torre, K.R.; Kosteski, L.E.; Marangon, E.; Riera, J.D. Influence of contact friction in compression tests of concrete samples. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317, 125811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mier, J.G.M. Chapter 7 - Combined Tensile and Shear Fracture of Concrete. In Concrete Fracture: A Multiscale Approach; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mier, J.G.M. Strain-softening of concrete under multiaxial loading conditions; Eindhoven University of Technology, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstle, K.B.; Aschl, H.; Bellotti, R.; Ko, H.Y.; Linse, D.; Newman, J.B.; et al. Behavior of Concrete Under Multiaxial Stress States. J. Eng. Mech. Div. 1980, 106, 1383–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mier, J.G.M. Chapter 8 - Compressive Fracture. In Concrete Fracture: A Multiscale Approach; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rutland, C.A.; Wangb, M.L. The Effects of Confinement on the Failure Orientation in Cementitious Materials Experimental Observations. 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain Softening of Concrete - Test Methods for Compressive Softening. RILEM TC 148-SSC; Mater. Struct. 2000.

- Khan, M.M.; Iqbal, M.A. Impact of End Friction and Lateral Inertia Confinement on the Dynamic Compressive Performance of Standard and High-Strength Concrete. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2024, 24, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mier, J.G.M.; Shah, S.P.; Arnaud, M.; Balayssac, J.P.; Bascoul, A.; Choi, S.; et al. Strain-softening of concrete in uniaxial compression. Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 1997, 30, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution. BS EN 12390-3:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete. Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. 2019.

- Gonnerman, H.F. Effect of size and shape of test specimen on compressive strength of concrete. Proc. ASTM 1925, 25, 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, G.F.; Schneider, L.M. Bulletin 5: Earth-wall Construction, 4th ed.; CSIRO Division of Building, Construction and Engineering: Sydney, Australia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.; Standards Australia. HB 195 - The Australian Earth Building Handbook; Standards Australia International Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Standards New Zealand. NZS 4298:1998; Materials and Workmanship For Earth Buildings. 1998.

- Standards New Zealand. NZS 4297:1998; Engineering Design of Earth Buildings. 1998.

- Standards New Zealand. NZS 4297:2020; Engineering Design of Earth Buildings. 2020.

- Bureau of Indian Standards. IS 4332-5:1970; Methods of Test for Stabilized Soils, Part 5: Determination of Unconfined Compressive Strength of Stabilized Soils. 1970.

- Walker, P.; Stace, T. Properties of some cement stabilised compressed earth blocks and mortars. Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 1997, 30, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, D.C.; Nayak, S. Utilization of granulated blast furnace slag and cement in the manufacture of compressed stabilized earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, H.; Martinson, D.B.; Ali, M.; Williams, J.B. Physical, mechanical and durability properties of soil building blocks reinforced with natural fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.C.J.; Guerrero, I.C. Earth building in Spain. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, P.T.; Herskedal, N.A.; Jansen, D.C.; Qu, B. Out-of-plane structural response of interlocking compressed earth block walls. Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 2015, 48, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.C.; Pkla, A.; Walker, P. Compressive strength testing of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, P.; Obonyo, E. Earthen construction materials: Assessing the feasibility of improving strength and deformability of compressed earth blocks using polypropylene fibers. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.C.J.; Guerrero, I.C. Earth building in Spain. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitton, J.D.; Zeinali, Y.; Heidarian, W.H.; Story, B.A. Effect of mix design on compressed earth block strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamizar, M.C.N.; Araque, V.S.; Reyes, C.A.R.; Silva, R.S. Effect of the addition of coal-ash and cassava peels on the engineering properties of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards New Zealand. NZS 4299:1998; Earth Buildings Not Requiring Specific Design. 1998.

- Standards New Zealand. NZS 4299:2020; Earth Buildings Not Requiring Specific Engineering Design. 2020.

- Bureau of Indian Standards. IS 1725:2023, Stabilized Soil Blocks Used in General Building Construction - Specification. 2023.

- Krefeld, W.J. Effect of Shape of Specimens on the Apparent Compressive Strength of Brick Masonry. In Proceedings of the American Society of Materials; 1938; pp. 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.; Keable, R.; Martin, J.; Maniatids, V. Rammed Earth Design and Construction Guidelines; BRE Bookshop: Watford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D1633 - 00; Standard Test Methods for Compressive Strength of Molded Soil-Cement Cylinders. 2007; pp. 1–15.

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ATSM C42/C42M, Obtaining and Testing Drilled Core and Sawed Beams of Concrete. 2004, 6. [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM C39/C39M, Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens; 2001; pp. 1–5.

- British Standards Institution. BS EN 13791:2019; Assessment of In-Situ Compressive Strength in Structures and Precast Concrete Components. 2019.

- British Standards Institution. BS EN 12390-1:2021; British Standard. 2021; p. 18.

- Rangasamy, G.; Mani, S.; Senathipathygoundar Kolandavelu, S.K.; Alsoufi, M.S.; Mahmoud Ibrahim, A.M.; Muthusamy, S.; Panchal, H.; Sadasivuni, K.K.; Elsheikh, A.H. An extensive analysis of mechanical, thermal and physical properties of jute fiber composites with different fiber orientations. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D7012 - 14, Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength and Elastic Moduli of Intact Rock Core Specimens under Varying States of Stress and Temperatures; 2014; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D5102 - 22; Standard Test Method for Unconfined Compressive Strength of Compacted Soil-Lime Mixtures. 2022; pp. 0–7. [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution. BS 1377-7:1990; Soils for Civil Engineering Purposes — Part 7: Shear Strength Tests (Total Stress). 1990.

- Danso, H.; Martinson, D.B.; Ali, M.; Williams, J.B. Mechanisms by which the inclusion of natural fibres enhance the properties of soil blocks for construction. J. Compos. Mater. 2017, 51, 3835–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, H.; Martinson, D.B.; Ali, M.; Williams, J. Effect of fibre aspect ratio on mechanical properties of soil building blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 83, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, H.; Martinson, B.; Ali, M.; Mant, C. Performance characteristics of enhanced soil blocks: A quantitative review. Build. Res. Inf. 2015, 43, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution. BS 8601:2013; Specification for Subsoil and Requirements for Use. 2013.

- British Standards Institution. BS 1377-2:2022; Methods of Test for Soils for Civil Engineering Purposes, Part 2: Classification Tests and Determination of Geotechnical Properties. 2022.

- Mastersizer 3000+ Lab; Malvern Panalytical Ltd., 2024.

- Morton, T. Earth Masonry: Design and Construction Guidelines; IHS BRE Press: Bracknell, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Liu, J.; He, K.; Ahmad, W. A comprehensive overview of jute fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.R.; Kozan, O.; Rahman, A.; Islam, K.; Hossain, M.I. Jute retting process: Present practice and problems in Bangladesh. Agric. Eng. Int.: CIGR J. 2015, 17, 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Al Jubayer, A.; Sheikh, B.; Rahman, M.; Islam, J.M.M.; Thakur, V.K. Modification of Jute Fibers by Radiation-Induced Graft Copolymerization and Their Applications. In Cellulose-Based Graft Copolymers: Structure and Chemistry; CRC Press, 2015; pp. 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Stochino, F.; Farina, I.; Valdes, M.; Fraternali, F.; Martinelli, E. Physical and mechanical characteristics of raw jute fibers, threads and diatons. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.; Hussain, M.; Levacher, D. Recycling of Tropical Natural Fibers in Building Materials. Nat. Fiber 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juradin, S.; Jozić, D.; Grubeša, I.N.; Pamuković, A.; Čović, A.; Mihanović, F. Influence of Spanish Broom Fibre Treatment, Fibre Length, and Amount and Harvest Year on Reinforced Cement Mortar Quality. Buildings 2023, 13, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, R.G.; Ramakrishna, G. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of economical local natural fibre reinforced cement mortar. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 7633–7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathavan, M.; Sakthieswaran, N.; Babu, O.G. Experimental investigation on strength and properties of natural fibre reinforced cement mortar. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview of ZwickRoell Materials Testing Machines; ZwickRoell Ltd., 2023.

- Genlab Classic Ovens, Genlab Ltd, 2020.

- Danso, H.; Martinson, D.B.; Ali, M.; Williams, J.B. Effect of Sugarcane Bagasse Fibre on the Strength Properties of Soil Blocks. In 1st International Conference on Bio-Based Building Materials; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Danso, H.; Martinson, D.B.; Ali, M.; Williams, J.B. Mechanisms by which the inclusion of natural fibres enhance the properties of soil blocks for construction. J. Compos. Mater. 2017, 51, 3835–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, H. Use of agricultural waste fibres as enhancement of soil blocks for low-cost housing in Ghana 2016.

- British Standards Institute. BS EN 772-1:2011+A1:2015; Methods of Test for Masonry Units. Determination of Compressive Strength. 2011.

- Ansys 2024 Product Release and Updates; ANSYS Incorporated, 2024.

- Ansys SpaceClaim 3D Modeling Software; ANSYS Incorporated, 2024.

- Yu, W.; Jin, L.; Du, X. Experiment and meso-scale modelling on combined effects of strain rate and specimen size on uniaxial-compressive failures of concrete. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2023, 32, 683–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.I.; Bru, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Ivorra, S. Masonry micromodels using high order 3D elements. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 11, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klabník, M.; Králik, J. Equivalent Stress and Strain of Composite Column under Fire. Procedia Eng. 2017, 190, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehdehi, R.; Panahshahi, N. Effect of openings on in-plane structural behavior of reinforced concrete floor slabs. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmar, N.; Bouziadi, F.; Boulekbache, B.; Meziane, E.; Hamrat, M. Experimental and finite element analysis of shrinkage of concrete made with recycled coarse aggregates subjected to thermal loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247, 118564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Atamturktur, S. Experimental and numerical evaluation of reinforced dry-stacked concrete masonry walls. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.C.; Özkaya, S.G. The finite element analysis of collapse loads of single-spanned historic masonry arch bridges (Ordu, Sarpdere Bridge). Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 84, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccoli, L.; Garofano, A.; Fontana, P.; Müller, U. Experimental testing and finite element modelling of earth block masonry. Eng. Struct. 2015, 104, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ayed, H.; Limam, O.; Aidi, M.; Jelidi, A. Experimental and numerical study of Interlocking Stabilized Earth Blocks mechanical behavior. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 7, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nabouch, R.; Bui, Q.-B.; Perrotin, P.; Plé, O.; Plassiard, J.-P. Numerical modeling of rammed earth constructions: analysis and recommendations. In 1st International Conference on Bio-Based Building Materials; 2015; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, F.; Balestrieri, C.; Varum, H. Nonlinear finite element model for traditional adobe masonry. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikon Metrology NV. XT H 225 and XT H 320. 2023.

- Reddy, B.V.; Jagadish, K.S. The static compaction of soils. Geotechnique 1993, 43, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selescadevi, T.S.; Thanjavur Varshini, S.V. Earth Building Blocks Reinforced with Jute and Banana Fiber; 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Karmaker, A.C.; Hinrichsen, G. Effect of water uptake on some physical properties of jute fibres. J. Text. Inst. 1994, 85, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Khan, M.A.; Zaman, H.U.; Pervin, S.; Khan, N.; Sultana, S.; et al. Comparative studies of mechanical and interfacial properties between jute and e-glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minitab Inc. Minitab 17.3.1 2024.

- Bouhicha, M.; Aouissi, F.; Kenai, S. Performance of composite soil reinforced with barley straw. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Shi, B.; Ng, C.W.W.; Tang, C.s. Effect of polypropylene fibre and lime admixture on engineering properties of clayey soil. Eng. Geol. 2006, 87, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Readle, D.; Coghlan, S.; Smith, J.C.; Corbin, A.; Augarde, C.E. Fibre reinforcement in earthen construction materials. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.: Constr. Mater. 2016, 169, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya-Letelier, G.; Antico, F.C.; Burbano-Garcia, C.; Concha-Riedel, J.; Norambuena-Contreras, J.; Concha, J.; Saavedra Flores, E.I. Experimental evaluation of adobe mixtures reinforced with jute fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 276, 122127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Block Dimensions (mm) | Aspect Ratio (H/W) | Reference | ||

| Length (L) | Width (W) | Height (H) | ||

| 295 | 140 | 125 | 0.89 | [54] |

| 305 | 143 | 105 | 0.73 | [55] |

| 290 | 140 | 100 | 0.71 | [56] |

| 300 | 140 | 100 | 0.71 | [57] |

| 300 | 150 | 100 | 0.67 | [58] |

| 295 | 140 | 90 | 0.64 | [59] |

| 300 | 150 | 95 | 0.63 | [30] |

| 203 | 191 | 121 | 0.63 | [60] |

| 295 | 145 | 90 | 0.62 | [61] |

| 305 | 152 | 89 | 0.59 | [62] |

| 320 | 150 | 80 | 0.53 | [63] |

| Material | Diameter (mm) | Aspect Ratio (H/D) | Correction Factor | Reference |

| Rammed Earth | 150 | 2.00 | - | [68] |

| 100 | 2.00 | - | ||

| 105 | 1.10 | 0.70 | ||

| Soil-Cement Cylinders | 71.1 | 2.00 | - | [69] |

| 101.6 | 1.15 | 0.91 | ||

| ASTM: Cylindrical Concrete Specimens | 150 | 1.80 | - | [70] |

| 1.75 | 0.98 | |||

| 1.50 | 0.96 | |||

| 1.25 | 0.93 | |||

| 1.00 | 0.87 | |||

| ASTM: Concrete Core Samples | ≥ 94 | 1.80 | - | [71] |

| 1.75 | 0.98 | |||

| 1.50 | 0.96 | |||

| 1.25 | 0.93 | |||

| 1.00 | 0.87 | |||

| British Standards Institution: Concrete Core Samples | 75 | 2.00 | - | [72] |

| 1.00 | 0.82 |

| Properties | Soil Type | |

|

Soil A: Kent Brick Earth with Marine Sand |

Soil B: BS 8601 Subsoil |

|

| Proctor Test | ||

| Optimum Moisture Content (%) | 13.6 | 17.5 |

| Maximum Dry Density (kg/m3) | 1900 | 1680 |

| Atterberg Limits | ||

| Liquid Limit LL (%) | 26.3 | 33.7 |

| Plastic Limit PL (%) | 15.3 | 25.9 |

| Soil Classification | ||

| Unified Soil Classification System | CL | ML |

| Particle Size Distribution | ||

| Gravel (> 2.0 mm) (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sand (2.0 – 0.063 mm) (%) | 38.8 | 68.0 |

| Silt (0.063 – 0.002 mm) (%) | 50.1 | 15.0 |

| Clay (<0.002 mm) (%) | 11.1 | 17.0 |

| Property: | Value: |

| Number of Bast Fibre Bundles Per Yarn | 119 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1122 |

| Cross-Sectional Area (mm2) | 0.2 |

| Tensile Strength (N/mm2) | 248 |

| Natural Moisture Content Under Ambient Conditions (20 oC, 58 % Relative Humidity) |

13 |

| Time to Reach Fibre Saturation (Minutes) | 50 |

| Moisture Absorption at Saturation (%) | 205 |

| Cross-Sectional Swelling at Saturation (%) | 19 |

|

Sample Dimensions |

Illustration | Aspect Ratio* | Mix Design Sample Reference | |||

| BE | FRBE | SS | FRSS | |||

|

Kent Brick Earth |

Fibre Reinforced Kent Brick Earth |

BS8601 Subsoil |

Fibre Reinforced BS8601 Subsoil | |||

| 150 mm (L) × 75 mm (W) × 50 mm (H) |  |

0.67 | BE-CEB | FRBE-CEB | SS-CEB | FRSS-CEB |

| 21.8 mm (H) × 43.6 mm (ø) |  |

0.50 | BE-0.50 | FRBE-0.50 | SS-0.50 | FRSS-0.50 |

| 32.7 mm (H) × 43.6 mm (ø) |  |

0.75 | BE-0.75 | FRBE-0.75 | SS-0.75 | FRSS-0.75 |

| 43.6 mm (H) × 43.6 mm (ø) |  |

1.00 | BE-1.00 | FRBE-1.00 | SS-1.00 | FRSS-1.00 |

| 65.4 mm (H) × 43.6 mm (ø) |  |

1.50 | BE-1.50 | FRBE-1.50 | SS-1.50 | FRSS-1.50 |

| 87.2 mm (H) × 43.6 mm (ø) |  |

2.00 | BE-2.00 | FRBE-2.00 | SS-2.00 | FRSS-2.00 |

| Sample Reference | Aspect Ratio (Target vs Actual) |

Dry Density (kg/m3) |

||||

| 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | ||

| BE | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 1.52 | 2.02 | 1926 ± 18 |

| FRBE | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 1.52 | 2.02 | 1911 ± 13 |

| SS | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 1.51 | 2.01 | 1718 ± 22 |

| FRSS | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.02 | 1.53 | 2.02 | 1685 ± 28 |

| Average (mean) value ± standard deviation n = 25 (Dry Density). | ||||||

| Aspect Ratio | Sample Reference | |||

| SS | BE | FRSS | FRBE | |

| 0.50 | A | A | B | B |

| 0.75 | A | A | B | B |

| 1.00 | A | A | B | B |

| 1.50 | A | A | A | A |

| 2.00 | A | A | A | A |

| Sample Reference | Aspect Ratio | Dry Density (kg/m3) | Compressive Failure Stress (MPa) |

| BE | 0.63 | 1951.9 ± 15.4 | 5.53 ± 0.33 |

| FRBE | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 1934.0 ± 14.2 | 9.64 ± 0.74 |

| SS | 0.64 | 1701.3 ± 10.3 | 4.19 ± 0.21 |

| FRSS | 0.65 | 1658.3 ± 8.8 | 7.87 ± 0.46 |

| Average (mean) value ± standard deviation, whereby n = 3. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).