1. Introduction

In the field of advanced heat transfer applications, Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMS) have emerged as a promising solution. TPMS are periodic surfaces characterized by zero mean curvature and no self-intersections, typically defined through trigonometric (sine and cosine) functions in the three spatial directions. Their distinctive advantage lies in their highly interconnected and complex lattice architecture, which increases the surface area-to-volume ratio and promotes efficient heat exchange. At the same time, the smooth and continuous nature of TPMS, free from sharp edges and dead zones, helps minimize pressure losses, enabling enhanced convective heat transfer with limited flow resistance. Among their various uses, TPMS have shown particular potential in heat sinks (HS) and heat exchangers (HX).

Despite being relatively recent in the context of heat transfer research, several review papers have already been published on TPMS applications [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These reviews address topics such as TPMS design, recent advancements, application potential in HS and HX, and fabrication via additive manufacturing (AM) techniques.

In Dutkowski et al. [

1], approximately 120 publications are analyzed, including studies focusing on the mechanical and manufacturing aspects of TPMS lattices. The authors emphasize the limited availability of experimental data related to thermal performance and advocate for broader CFD-based exploration of TPMS topologies, beyond the most frequently studied ones. They also highlight the need for an interdisciplinary approach to support the development of TPMS-based thermal systems.

Yeranee and Rao [

2] provide a focused review on heat transfer applications of TPMS lattices, particularly in HS and HX, considering topologies such as Gyroid, Diamond, Primitive, and I-WP. Around 100 studies are analyzed, primarily numerical, covering both laminar and turbulent regimes, and exploring the influence of design parameters – such as porosity, wall thickness, and unit cell size – on thermal and fluid-dynamic performance. The review also includes an overview of AM techniques suitable for TPMS fabrication. Given the increasing feasibility of producing and testing TPMS in experimental setups, the authors stress the importance of experimental validation. They suggest techniques such as liquid crystal thermography, thermocouples, and MRI for characterizing flow and temperature fields. A key limitation identified is the absence of reliable heat transfer correlations at high Reynolds numbers, motivating the need for further experimental campaigns and optimization studies.

The review published in 2024 by Gado et al. [

3] includes a bibliometric keyword analysis of around 150 papers. It extends the scope of covered topologies (including Neovius, FKS, and FRD), and reviews both HS and HX applications with air and water as the most frequent working fluids. The paper summarizes computational studies, details friction factor and Nusselt correlations, and provides insights into numerical software and AM methods. It also outlines new emerging applications for TPMS-based components, such as compact heat exchangers, latent heat thermal energy storage (TES), adsorption systems, battery thermal management, and membrane distillation. Additional use cases are identified in photovoltaic (PV) and fuel cell thermal control, adsorption cooling and desalination systems, atmospheric water harvesting, carbon capture, thermochemical sorption energy storage, and desiccant-based air conditioning. However, the bibliometric analysis has been used only to identify relevant papers, and the review does not provide a systematic categorization of the literature based on criteria or attributes that would help readers quickly locate studies on specific topics (e.g., Diamond-topology heat sinks using water as the working fluid under turbulent conditions).

This specific point is partly addressed by the most recent review of Wang et al. [

4], published in 2025, that focuses exclusively on the flow and heat transfer performance of TPMS. It analyzes more than 90 papers dealing with the applications of TPMS to thermal management systems, among which heat sinks and heat exchangers. The effect of unit cell size is addressed, and several topologies are analyzed, also reporting the comparison to traditional designs. Notwithstanding the valuable amount of information provided by [

4], it partially fails in facilitating navigation in the paper database, as the emphasis is on comparing the results obtained by different scholars rather than comparing the different features that characterize the different analyses.

Despite the valuable insights provided by these reviews, a significant limitation common to all is the lack of clarity, transparency and reproducibility in the methodology used to select the reviewed publications. Even in [

3] and [

4], the inclusion criteria are not explicitly defined, making it difficult to assess the completeness and potential biases of the findings. A standardized, transparent, and reproducible paper selection process would enhance the reliability and scope of future reviews. As also highlighted in [

3] and [

4], the TPMS research domain is evolving rapidly, underscoring the need for regular updates to track emerging trends and innovations. However, systematic reviews can only be conducted effectively if supported by a clear and rigorous methodology for the identification and classification of relevant literature.

The objective of this paper is to conduct, for the first time, a comprehensive and systematic literature investigation of TPMS applications in heat transfer problems, based on a structured selection and analysis framework. The adopted methodology is the APISSER framework [

5], a task-oriented extension of the PRISMA protocol [

6], specifically tailored to engineering-focused reviews that require metadata classification and topic filtering.

This investigation includes peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 2000 and 2024, identified through a keyword-based search combined with explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria. For each paper, a consistent set of attributes is extracted—such as the experimental or numerical nature of the study, the modelling and geometry-generation tools employed, the working fluids, the flow regime, the AM technique, and the presence of validation—allowing the construction of a structured database.

This categorisation goes beyond the scope of previous reviews (e.g. [

4]), which typically focused on comparing thermal figures of merit. Here, the metadata-driven approach provides a broader, systematic perspective on publication trends, modelling practices, and geometric choices, thereby enabling a more comprehensive mapping of the state of the art. The method adopted for the analysis allows, as a byproduct, the sorting of the papers based on a specific attribute among those used for categorizing the papers. The paper list, reported in the reference section in alphabetic order to ease the identification of the scholars contribution, and the corresponding database, available as electronic supplementary material, can become a viable tool to find research works that better cover a specific aspect of interest (e.g., papers dealing with heat sinks, with experimental investigation involving air in laminar flow conditions). This transparent and repeatable approach improves the robustness of the findings and allows researchers to contextualize their work within the broader scientific landscape, as well as to identify gaps and underexplored areas.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the APISSER framework and its application to this review.

Section 3 discusses the main results of the analysis, while

Section 4 provides a focused application of the method to studies involving Gyroid and Diamond TPMS used in HS and HX. Final remarks and conclusions are given in

Section 5.

2. Methodology

This section outlines the selected methodology for conducting a systematic literature investigation adaptable for various engineering applications. The approach is based on the APISSER methodology [

5], an acronym that stands for "

A-priori,

Paper identification,

Inclusion/Exclusion screening,

Selection,

Structured data extraction,

Evaluation and

Reporting". It consists of the five phases shown in

Figure 1, to be rigorously followed in the given order to ensure reproducibility.

The process begins with the "A-priori phase", which establishes the foundation for the literature investigation. In this phase, specific knowledge gaps or problems within the topic of interest are identified and addressed through the formulation of precise "Research Questions" (RQs). The RQs are specific and focused on covering the areas where knowledge is lacking or fragmented; the more RQs are formulated, the more comprehensive the literature analysis will be. Collectively, the RQs should ensure the full coverage of the overall knowledge gap. The answers to the RQs automatically result in a set of attributes, based on which the papers in the database can be easily categorized and sorted.

The "

Identify phase" involves the creation of a database of potentially relevant papers. This phase begins with the selection of appropriate online databases (O-DB), such as Scopus [

7], Web of Science [

8], or IEEE Xplore [

9], depending on the field of study. The outcome of this phase is the so-called "Long Database" (L-DB), populated with publications that could potentially address the RQs. A detailed keyword query strategy is designed to retrieve potential papers by combining technical terms with related application areas. Boolean operators are utilized to refine the search criteria based on the specific O-DB. To assess whether the selected keywords are appropriate, the L-DB is compared against a set of benchmark publications known to be relevant in the field.

The "Screen & Select phase" refines the L-DB into a more focused Short Database (S-DB) by applying explicit eligibility criteria for the systematic inclusion or exclusion of papers. The process is conducted in two stages: an initial rapid assessment of titles and abstracts, followed by a detailed evaluation of the full texts for the studies that pass the preliminary check. To ensure reproducibility, each step of the selection procedure is documented in detail, allowing other researchers to replicate the methodology and achieve comparable results. Inclusion criteria (IN) define the essential requirements for selection, such as publication date, language, peer-review status, relevance to the topic, and alignment with the intended use case. In addition, a specific exclusion criterion (EXC1) is introduced to remove studies whose primary focus lies outside TPMS thermal applications, for example works dealing mainly with mechanical properties, scaffolds, bone tissue or fatigue. Papers that do not satisfy all the inclusion criteria, or that fall within EXC1, are discarded and not retained in the final dataset.

The "Extract phase" is devoted to the extraction of "Data Items" (DI), each explicitly linked to one or more RQ. The DI are the main content of the investigation, being the base for the successive Report phase. The number and type of DI extracted are to some extent subjective, as they may vary depending on the objectives and topics of the investigation. Some DI may be subcategories or combinations of others, which allows more focused findings; for example, an author might choose to investigate experimental papers specifically authored by European researchers, combining geographic and methodological aspects to refine the literature investigation.

Finally, the "Report phase" synthesizes the extracted data and communicates the findings in a structured format. The results are summarized to directly address the RQ. The results are categorized to capture trends that emerged from the analysis. This also gives relevant insights for identifying reasearch gaps, to be addressed in the future.

2.1. A Priori Phase

The topic of this systematic investigation is the application of TPMS in heat transfer problems, according to the 13 RQs synthetically reported in

Table 1 and briefly commented in the following.

With the increasing growth in TPMS research activity in the last years, it may be relevant to identify the geographical distribution of the publications (RQ1), to understand where the scientific and technological research is more active in this field. At the same time, monitoring the growth in research volume over recent years (RQ2) and analyzing its rate could help understanding if and how studies related to TPMS are still considered a relevant research direction. TPMS provide a promising solution for improving heat transfer in a variety of scopes, including, for instance, the pure heat transfer in HS and HX. Some investigations focus specifically on the hydrodynamic behavior within TPMS lattices. Although the hydraulic behavior is intrinsically related to heat transfer, it is not considered directly relevant to this investigation, see also below. Beyond purely thermal scopes, some studies are more closely related to chemical processes, addressing phenomena such as mass transfer, absorption, or the behavior of phase-change materials (PCMs) within TPMS lattices. The diversity of these topics makes it relevant to identify the scope of each contribution (RQ3).

When narrowing the analysis to heat transfer applications, it is necessary to specify the operational context in which each TPMS study is framed (RQ4). Excluding purely bibliographic contributions, the literature can be grouped into the following main categories:

Heat sinks, where TPMS lattices are used to enhance thermal dissipation from solid surfaces through single-phase forced convection.

Heat exchangers, in which TPMS structures enable heat transfer between two separate fluid streams, often aiming to maximize compactness and surface area while limiting pressure drop.

Free convection systems, where natural buoyancy effects govern fluid motion, typically in low-power or passive cooling scenarios involving air.

Material-centered studies, which focus on the effective thermal conductivity or storage capacity of TPMS-based solids, including configurations with embedded PCMs.

The studies focusing on heat transfer in TPMS lattices rely on different methodological approaches: some are based solely on experimental work, others on numerical simulations, while a third group combines both. Experimental investigations are essential for validating results and for capturing complex physical behaviors that may not be fully represented in simulations. On the other hand, numerical studies, often based on CFD, offer the flexibility to explore a wider range of operating conditions, geometries, and parameters. Identifying the methodological approach adopted in each study is therefore crucial to assess the robustness of the results and to guide future research efforts (RQ5).

Generating TPMS structures requires specialized software, which may differ in terms of modeling flexibility, meshing efficiency, and compatibility with 3D printing or CFD environments. The variety of tools adopted for TPMS geometry generation, never systematically investigated in previous reviews, is addressed in RQ6.

Different studies consider a variety of working fluids depending on the specific application. Common choices include air and water, while more specialized studies investigate molten salts, water-glycole mixtures and PCMs like paraffin (RQ7).

For the studies reporting experimental investigations on TPMS, it is relevant to understand the manufacturing methodology used in the 3D printing of the lattice (RQ8), as it may affect the measured results. Surface roughness may impact for instance pressure drop and heat transfer performance.

For the studies reporting numerical investigations, various software tools could be employed for numerical analysis, relying either on different approaches, e.g. Finite volume, Finite elements, Lattice Boltzmann and others. It is correspondingly relevant then to consider what is the numerical method and tool adopted for the analysis (RQ9), an aspect that has not deserved much attention in previous reviews.

Among the various TPMS structures, each topology offers distinct advantages depending on the intended application. Gyroid and Diamond lattices are the most extensively investigated, owing to their favourable thermo-hydraulic behaviour. They generally ensure higher heat-transfer rates than simpler geometries such as Primitive or Neovius, while inducing lower pressure drops compared to more intricate structures like Lidinoid or SplitP. Understanding how these topologies are distributed across different use cases is therefore essential for identifying emerging research directions and for contextualising performance comparisons presented in previous narrative reviews, which typically emphasise figures of merit rather than providing a comprehensive mapping of topology usage (RQ10).

Beside the selection of the most suited topology, the effectiveness of TPMS designs in heat transfer applications also depends on the flow conditions, particularly whether the regime is laminar or turbulent. Investigating the most frequently studied flow regimes (RQ11) can provide valuable insights into TPMS behavior under different operating scenarios, while also highlighting gaps in current research.

For numerical studies involving turbulent flows, the choice of turbulence closure model (RQ12) plays a key role. Identifying which models, such as Standard or Realizable k–, or k– SST, are most commonly adopted and can offer practical guidance for future simulations. This is particularly relevant when results are benchmarked against experimental data.

Finally, attention must be paid to the degree of validation provided for numerical findings (RQ13). While verification through mesh sensitivity analysis is often reported, actual validation–intended as comparison with measured data–is less common. Understanding which studies include such comparisons, and under what conditions, helps assess the overall reliability of the current numerical literature on TPMS-based systems.

2.2. Identify Phase

The bibliographic search is conducted using the O-DB Scopus [

7], selected for its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature in engineering and applied sciences. A dedicated query (Equation (1)) is designed using Boolean operators. These operators–such as

AND,

OR, and

AND NOT–allow for flexible and controlled combinations of keywords, enabling a targeted refinement of the search results. For a detailed explanation of Boolean syntax in Scopus, the reader is referred to the official guidelines available at:

https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/11365/supporthub/scopus/#tips.

During the initial search, additional filters are applied directly within Scopus to narrow down the results and generate the L-DB. These filters correspond to inclusion criteria IN0 through IN3, which are summarized in

Table 2. Note that automated database searches frequently miss relevant papers due to inconsistencies or omissions in keyword usage. For instance, the hooking of certain papers clearly discussing TPMS may be excluded because they use variations like "Triple (instead of Triply) periodic minimal surface" [

10], "Triply periodic minimum (instead of minimal) surface" [

11] or "Triply periodical (instead of periodic) minimum (instead of minimal) surfaces" [

12]. These minor misprints prevent effective findings using keyword-based searches on platforms such as Scopus. Furthermore, some papers refer to TPMS implicitly by referencing general terms such as "lattices" [

13] without explicitly mentioning TPMS in their titles, keywords or abstracts. Others specify particular TPMS types, such as Gyroid or Diamond, without directly mentioning the acronym TPMS itself. Although careful reading confirms that those papers (for instance [

14,

15,

16,

17]) actually focus on TPMS, they remain difficult to locate through automated query methods. This problem underscores the importance of consistently and explicitly including key terms, such as TPMS, in the title or abstract, to increase visibility and accessibility of the paper. The acronym TPMS, however, does not unambiguously identify Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces, as it could also stay for Two-Phase ModelS, as in [

18], giving (a limited number of ) false-positive items in the L-DB. These papers have obviously been ruled out from the S-DB in the

Screen-and-Select phase.

2.3. Screen-and-Select Phase

This phase refines the L-DB to extract only those documents aligned with the specific objectives of this investigation. The screening begins by evaluating titles and abstracts for coherence with the topic, i.e. the use of TPMS for heat transfer applications. Papers unrelated to this focus are discarded.

During this step, exclusion criterion EXC1 is applied. This removes studies primarily concerned with mechanical performance or biological applications, such as those referring to “scaffold”, “bone” or “fatigue.” Importantly, EXC terms are not excluded in the initial Scopus query, since papers containing these terms may still offer useful insight for heat transfer applications, e.g., those addressing lattice permeability, provided theuy mention explicitly thermal aspects.

After title and abstract screening, a full-text review is carried out. Only studies satisfying the remaining inclusion criteria - specifically those addressing

thermal-hydraulic TPMS applications (IN4), those presenting

at least one thermal use case (IN5) and those related to specific subject areas (IN6) - are retained. During this stage, false positives from the earlier query are filtered out. More in detail, several studies dealing only with hydraulic aspects (such as determination of the lattice permeability, see [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]) but with no link to thermal applications are identified and filtered out.

The resulting set of documents constitutes the S-DB, which includes only the core studies and is provided as supplementary material.

2.4. Extract Phase

The

Extract phase is devoted to the identification and registration of a set of

Data Items, each explicitly linked to one or more

Research Questions, in order to ensure consistency between the collected metadata and the objectives of the review. The full list of DIs is provided in

Section 2.4.

The DIs were selected to comprehensively address the knowledge gaps outlined in the RQs reported in

Table 1. In this context, each DI serves as a container for information or attributes extracted from the selected studies, contributing directly to answering one or more RQs. Depending on the scope of analysis, statistical observations can be derived either from individual DIs or from the correlation of multiple items.

A visual summary of all the above phases is provided in

Figure 1.

Table 3.

Data Items selected for the evaluation of the results.

Table 3.

Data Items selected for the evaluation of the results.

| ID |

Data Item |

| DI1 |

Country of the publication |

| DI2 |

Year of publication |

| DI3 |

Scope of the study |

| DI4 |

Specific application within the heat transfer domain |

| DI5 |

Focus of the study: experimental, numerical, or both |

| DI6 |

TPMS geometry generation tool |

| DI7 |

Working fluid used in the study |

| DI8 |

Additive manufacturing (AM) method |

| DI9 |

Numerical software employed |

| DI10 |

TPMS topology (e.g., Gyroid, Diamond, etc.) |

| DI11 |

Flow regime: laminar, turbulent, or transitional |

| DI12 |

Turbulence model (for turbulent simulations) |

| DI13 |

Presence of validation (experimental or numerical) |

3. Results of the Investigation

This section presents the results derived from the systematic investigation conducted through the APISSER framework, corresponding to the final Report phase. From an initial pool of over 1400 papers collected in the L-DB, a total of 130 studies were selected and included in the S-DB [

10,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163], excluding the three review papers previously discussed. Each of the following subsections analyses the selected studies with reference to one or more specific DIs, as defined in the methodology.

3.1. DI1 and DI2: Country and Year of the Publications

The map in

Figure 2 illustrates the global distribution of scientific contributions on the topic of interest, based on the affiliation of the first author of the paper. Each country is coloured according to the number of published studies, with darker shades indicating higher research activity. China leads significantly the worldwide picture with 62 publications, followed by the United Arab Emirates (14), the United States and Canada (7), Italy (5), Japan and Egypt (4). Countries without contributions are coloured with the lightest colour. This visualization reveals a geographically uneven research effort on the topic at hand, suggesting that there is potentially room for capacity building through international collaboration involving the few places with the strongest know-how.

Figure 2 shows in the inset the temporal evolution of the papers in the S-DB from 2019 to 2024 (being the number of papers published prior to 2019 almost negligible), as resulting for the DI2. A clear upward trend is shown, especially from 2020 on, with an exponential increase in the total number of studies. The latest year of the investigation, i.e. 2024, marks a significant peak with more than 70 papers published, indicating a rapid recent acceleration of interest in this topic, which appears to be confirmed by the 2025 trend, not addressed specifically in the analysis. The contribution from China shows a particularly steep rise, aligning with its dominant position shown in

Figure 2.

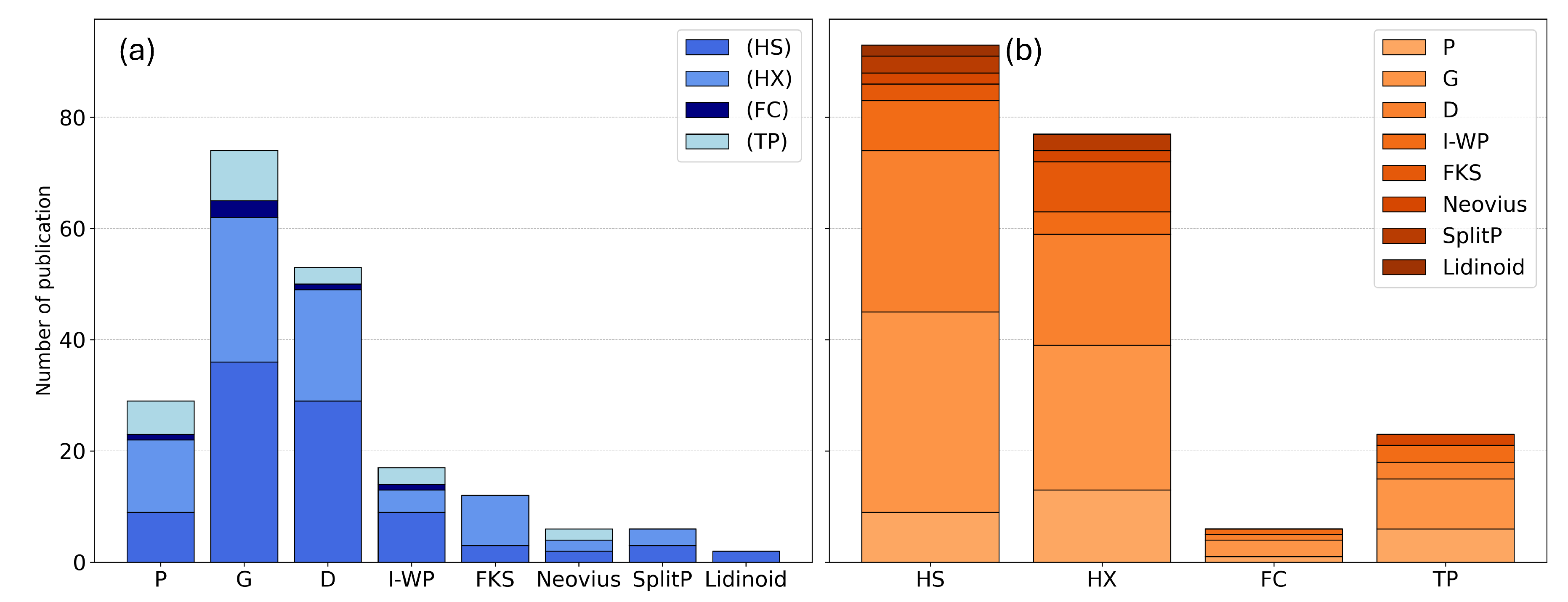

3.2. DI3 and DI4: Scope and Specific Application

The classification of the selected papers according to the different scopes (DI3) is reported in

Figure 3, where the most common applications for TPMS lattices within the heat transfer scope (DI4) are also shown. The novelty of TPMS enables research across a broad range of topics, including flow behavior, mass transfer and absorption phenomena, and the performance of phase-change materials. As for the chosen articles, heat transfer is the main investigated aspect, unsurprisingly this category alone represents roughly two-third of the total analyzed studies, as expected from the adoption of inclusion criteria IN4 and IN5 in the

Screen-and-Select phase. Within this group, as detailed in the pie chart, the majority of contributions concern heat sinks (a), followed by heat exchangers (b), and, to a smaller extent, investigations on free convection (c) and thermo-physical material properties (d). The last category also includes studies involving PCMs, where the main interest lies in the evaluation of the system effective thermal conductivity. Note that the same paper can tackle two different scopes, as for instance [

69], addressing PCM and thermo-physical properties, or [

70], dealing with PCM and free convection. A minority of studies address mass transfer or absorption/adsorption problems, see for instance [

55] (the only study related to two-phase flow in TPMS structures) and [

139] for the first topic and [

72,

73,

91,

92] for the second).

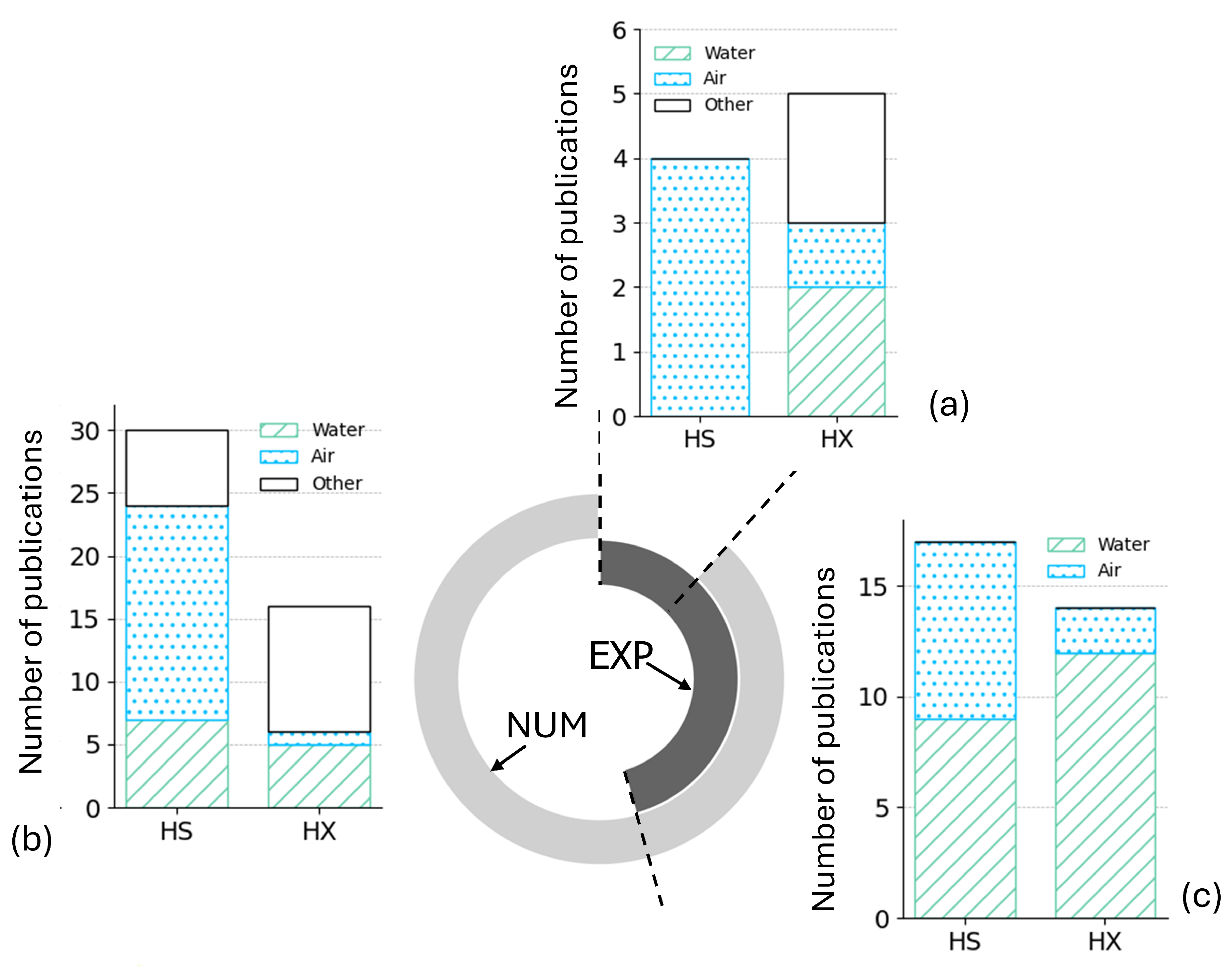

3.3. DI5 and DI7: Experimental vs Numerical Studies and Working Fluid

One of the most notable findings of this investigation concerns the focus of the study (DI5) and is illustrated in

Figure 4. Over 80% of the papers rely on numerical simulations, mostly using traditional CFD, but also Lattice Boltzmann approaches. Fewer than 20 studies are based exclusively on experimental work. More than 35 publications combine experimental measurements and numerical modeling. It is important to note, however, that reporting both experimental and numerical analyses does not necessarily imply that the numerical model was validated against the experimental data, see also DI13. Conversely, studies presenting only numerical results may still validate their findings using experimental benchmarks available in the literature. The comprehensive analysis carried out in this paper may serve both communities: it helps numerical researchers identify experimental datasets for validation purposes, offering at the same time experimentalists a structured overview of available numerical results that can support the design and interpretation of future tests. The experimental activity is overall dominated by investigations on HS, followed closely by HX.

A key factor influencing experimental studies on TPMS-based HS is the selection of the working fluid (DI7). As shown in

Figure 4, the most commonly employed fluids are water and air, due to their cost-effectiveness, well-known thermophysical properties, and suitability for laboratory-scale testing. These fluids enable reliable measurements while keeping experimental complexity and cost relatively low. A few HS studies also consider fluids tailored to specific industrial applications, highlighting the flexibility of TPMS systems: examples include helium [

133,

162], supercritical CO

2 [

58], and CH

4/N

2 mixtures [

56].

In the context of HX, the diversity of working fluid pairs is even more pronounced. While air and water remain the most frequent experimental choices, some studies use non-standard combinations, such as air/water [

114] and R134a/glycol water [

107]. On the numerical side, more complex pairings have been explored, reflecting the versatility of TPMS structures in different thermal management scenarios. These include helium/lead-bismuth eutectic (LBE) [

132,

137], oil with either fuel [

123] or water [

118], CO

2/H

2O [

93] or CO

2/CO

2 [

94], and acetone configurations [

49]. The wide variety of fluids adopted in both experimental and numerical investigations clearly raises a caveat regarding the comparability of results across different studies. Any meaningful comparison should rely exclusively on dimensionless quantities, whose definitions must be consistent and within similar ranges among the various works. This implies that, when the analysis focuses on heat transfer problems, not only the Reynolds number but also the Prandtl number should be comparable if any conclusions concerning the Nusselt number are to be drawn.

3.4. DI6: Type of TPMS Generator Tool

Independently on the focus of the selected papers on experiments or numerical analyses, the generation of the TPMS lattices typically requires the use of dedicated software: the portfolio of tools adopted in the selected papers is the output of DI6, reported in

Figure 5. The software MSlattice [

164], developed by scholars from UAE, is the most used in the considered papers, followed by nTop [

165], that provides powerful capabilities for generating and optimizing TPMS structures. Both tools are versatile, and allow the generation of highly detailed and application-specific geometries, also when functionally graded lattices are considered. MATLAB [

166], which is the third most used software, offers flexibility in developing custom TPMS geometries using mathematical functions and algorithms, with the ease of integration into a well-known simulation environment. Other tools are used by a minority of the scientific community: MathMod [

167], SolidWorks [

168], which makes the incorporation of TPMS into mechanical components possible, Siemens NX [

169], ANSYS SpaceClaim [

170], the Python-based Geodict [

171], Wolfram Mathematica [

172], Rhinoceros [

173], and others (MaSMaker [

174] and LattGen [

175]).

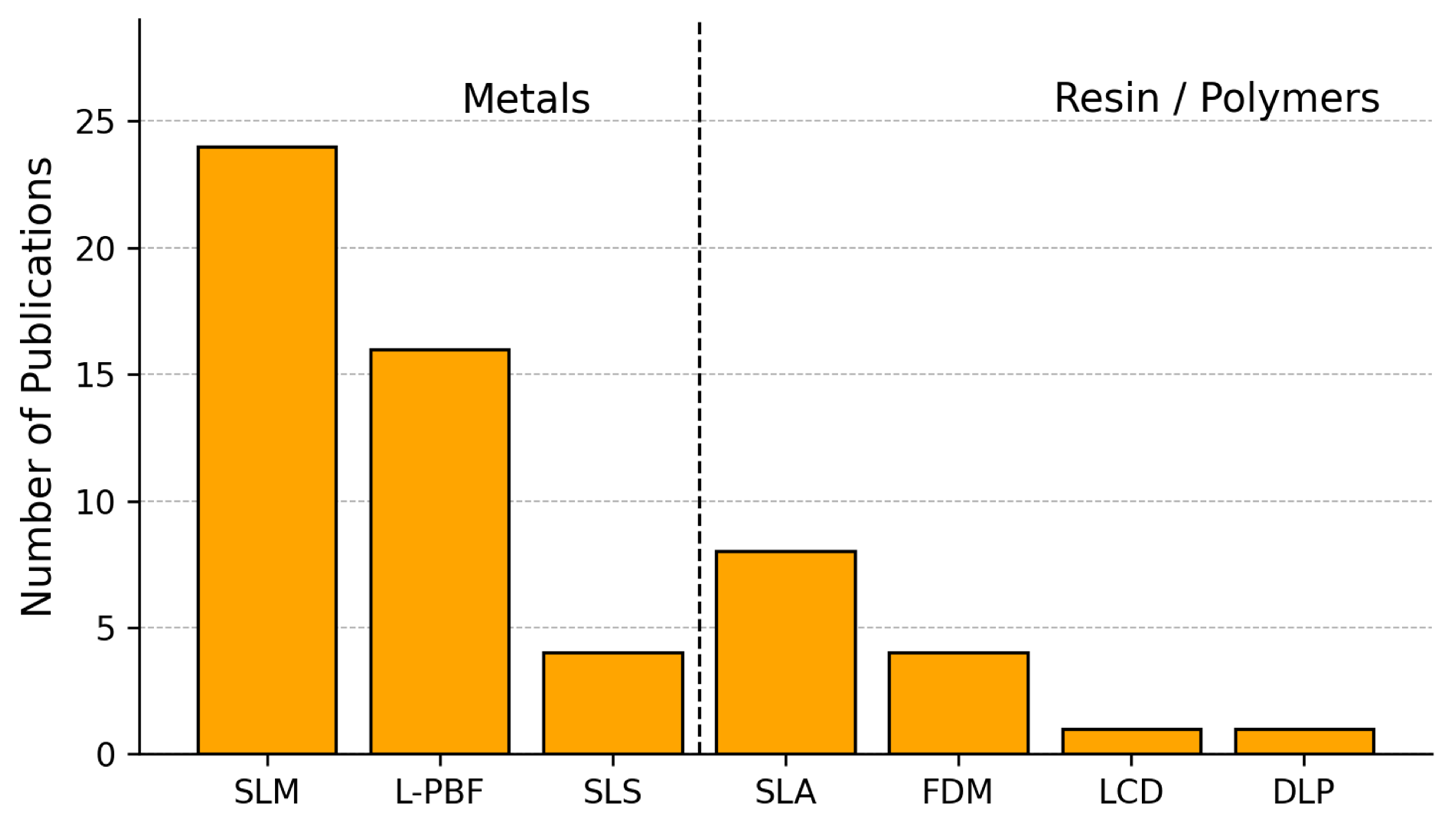

3.5. DI8: AM Methods

Figure 6 provides an overview of the AM techniques (DI8) adopted for the studies dealing with experimental tests. AM plays a crucial role in the fabrication of complex and highly optimized geometries such as TPMS, which are unrealizable through traditional manufacturing techniques, especially for metallic items. AM processes can be classified based on the type of energy source employed (if any) and the materials used. Among the variety of AM categories, Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) stands out as the most widely used for metallic parts. This technology creates components layer by layer by selectively fusing powdered material using a concentrated heat source. Usually, two energy sources are used, and they categorize PBF in two subgroups: Laser PBF (L-PBF) and Electron Beam PBF (EB-PBF). L-PBF is versatile, compatible with a wide range of metals and alloys. Its precision and flexibility facilitates the production of highly intricate TPMS structures, optimizing thermal performance and material efficiency [

176]. L-PBF methods include: Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Selective Laser Melting (SLM) and Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS).

Among the PBF techniques, SLM emerges as the most frequently employed for metal devices (more than 20 paper). SLM uses a high-powered laser to melt and fuse metallic powder according to a pre-defined pattern [

177]. SLS, primarily used for polimers, fuses powder particles without fully melting them [

178]. It is less common for metal production compared to SLM or DMLS as it usually results in porous or less dense parts, although some publications refer to this manufacturing techniques [

39,

130].

While similar in process, DMLS only partially fuses metal powder. Although it excels in processing complex alloys [

179], its application is very limited (only applied in [

27]).

Focusing on plastic or resin manufacture, Stereolithography (SLA) is the most widely adopted method. SLA is a photopolymerization method that employs a UV laser to cure liquid resin into solid layers. It offers high resolution and surface finish, making it suitable for producing detailed prototypes and components with fine features [

180]. Its relatively low cost and compact size make SLA printers particularly suitable for research laboratories, allowing rapid design iteration and experimental testing without the need for large-scale infrastructure. Note, however, that resin may be not suitable for tests with substantial heating in view of its softnening at relatively low temperatures.

Other techniques–such as Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), Digital Light Processing (DLP), and LCD-based vat photopolymerization–are adopted in a limited number of studies. In FDM thermoplastic filaments are extruded through a heated nozzle to build parts layer by layer. FDM belongs to the broader category called Material Extrusion, and is accessible, cost-effective, and versatile, making it popular for prototyping and low-volume production [

181]. Nevertheless, it has a lower resolution than SLA, making it less suitable for TPMS applications. LCD is a vat photopolymerization technique similar to SLA but differ in their light projection methods. DLP, adopted in [

126] uses a digital projector to cure entire layers simultaneously, while LCD-based 3D printing, used in [

114] and [

21], employs an LCD screen to selectively expose regions of the resin [

182].

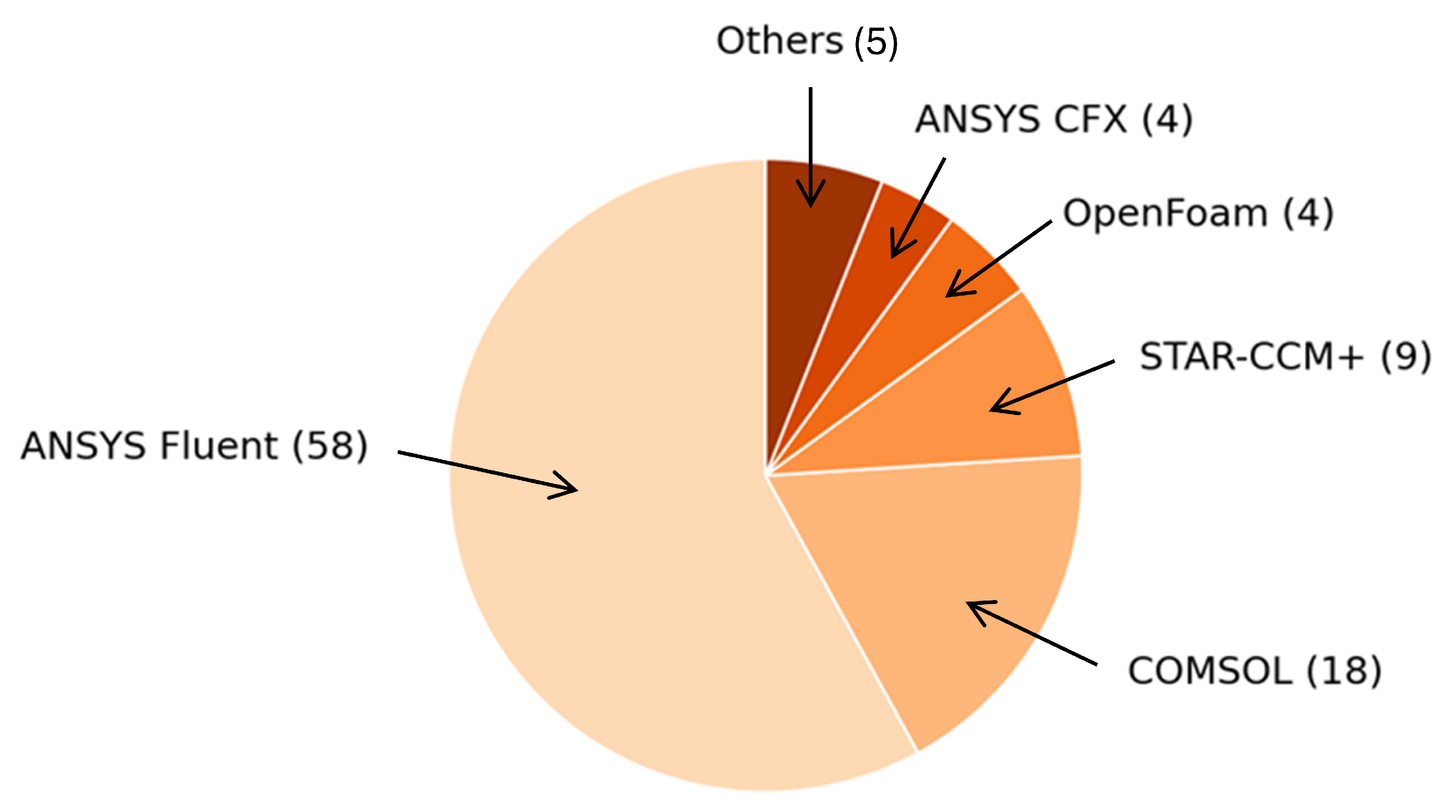

3.6. DI9: Numerical Software Used for Simulation

In studies categorized as

numerical according to DI5, the choice of the simulation software (DI9) is summarized in

Figure 7. The most widely used CFD tool is

ANSYS Fluent [

170], appreciated for its finite volume method, user-friendly interface, and robustness in handling both laminar and turbulent regimes. Similar characteristics are offered by

STAR-CCM+ [

183], which is the third most adopted software. The second most used platform is

COMSOL Multiphysics [

184], which employs the finite element method and is mostly adopted for simulations in laminar conditions or low-Reynolds-number flows, often involving conjugate heat transfer or coupled physics problems. Open-source tools are less frequently employed:

OpenFOAM [

185], while powerful and highly customizable, appears in a limited number of studies. Its reduced adoption may be attributed to the steeper learning curve and, notably, to the challenges related to mesh generation, which is often more cumbersome than in commercial tools. However, this limitation can be overcome by importing meshes generated with more user-friendly software. Other software tools such as

Simerics-MP+ [

186] and

SolidWorks Flow Simulation [

187] are mentioned only in single studies, typically in turbulent regimes.

Palabos [

188], a Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) solver, is only sporadically used (and not shown in

Figure 7). Despite its strengths in simulating complex boundary interactions and mesoscale transport phenomena, it has not yet gained widespread adoption in the TPMS heat transfer community.

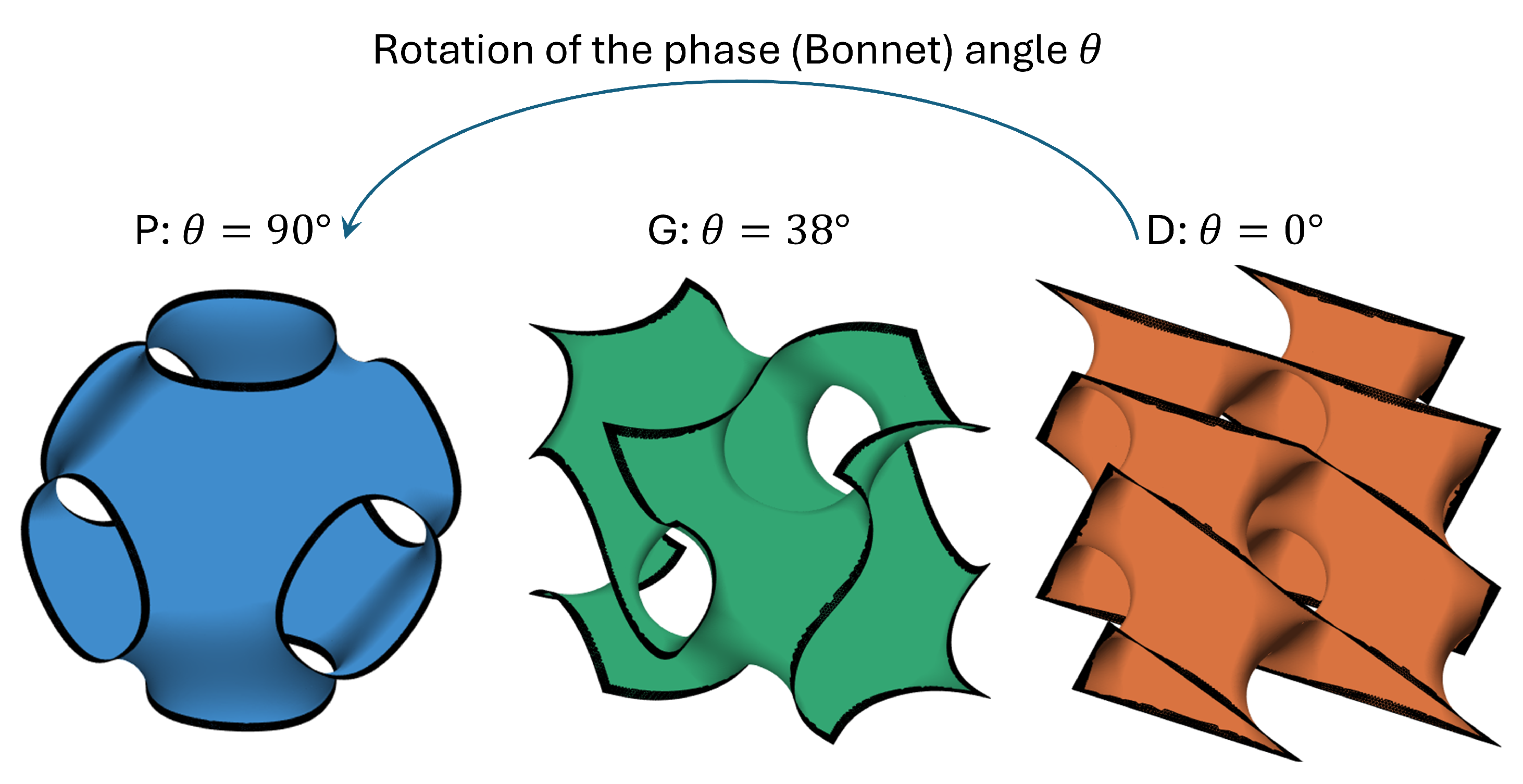

3.7. DI10: TPMS Topologies

A wide variety of TPMS topologies have been investigated in the S-DB papers. Each structure presents distinct geometrical features that influence its suitability for different heat transfer applications. The Primitive (P), Diamond (D) and Gyroid (G) surfaces form the classical associate family of TPMS. This means that they share the same conformal structure and can be continuously transformed into one another through a simple rotation of a phase angle

– the Bonnet angle – in their complex Weierstrass–Enneper representation, as exemplary shown in

Figure 8. The period-closure conditions are verified for just three values of

(0°, 38° and 90°), whereas all the other rotations give self-intersecting surfaces [

189]. From the morphology point of view, the D lattice has a cubic Primitive (CP) structure as the Diamond in nature, whereas both the P and G lattices share a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure. However, the P lattice has mirror planes perpendicular to the cubic axes, corresponding to a non-chiral symmetry, while the G lattice features diagonal glide planes, originating a chiral geometry. This point is important because all the other topologies discussed in this study originate from one of these base surfaces (P,G,D) and consequently inherit the lattice symmetry and morphology of their parent structure.

A visual summary of the most commonly adopted topologies is provided in

Table 4, which includes for each topology: the sheet and solid (sometimes referred to as "network", as in [

4]) variants, the two fluid domains (according to the set-level function), and the corresponding analytical expression of the level-set surface.

The

Gyroid topology, as shown in

Figure 9, is the most widely studied, especially in applications involving heat sinks. It is appreciated for its favorable combination of surface area, fluid accessibility, and mechanical stability, which contribute to improved heat transfer compared to conventional extended surfaces [

119]. Although HS dominate its application domain, several studies have also successfully explored its use in HX.

The

Diamond lattice is the second most investigated structure and shares several performance similarities with the G topology. In particular, both are especially suitable for HX configurations, as they divide the domain into two self-complementary fluid regions when implemented in the sheet variant. This geometric peculiarity–also shared by several other TPMS in

Table 4–facilitates the design of balanced HX configurations. Note, however, that, as opposed to the Gyroid topology, the Diamond topology is achiral.

The Primitive topology is characterized by a regular and open geometry, which facilitates fabrication and flow. It produces two identical domains and is occasionally employed in HS or HX studies. However, its high permeability and relatively low surface area makes it more suited to low-resistance applications, such as filters, which fall outside the scope of this investigation.

The

I-WP structure is recognized for its smooth morphology and high interconnectivity. While its mechanical and flow characteristics are advantageous, the two regions generated by the level-set function are not self-complementary, making its direct application in heat exchangers less straightforward. Nonetheless, it has been explored in advanced applications such as catalytic reactors and microscale exchangers [

190,

191,

192]. From a morphology standpoint, the I-WP surface is D-related, sharing the same CP lattice as the Diamond surface but with a lower symmetry. This symmetry reduction results in two morphologically distinct labyrinths, in contrast to the self-complementary nature of the parent D surface.

The

Fischer-Koch-S (FKS) lattice introduces a higher level of geometric complexity while preserving domain symmetry. Its intricate surfaces result in elevated area-to-volume ratios and have been employed in the design of compact micro-heat exchangers and energy storage devices [

107,

118,

133,

136]. From a geometrical standpoint, the FKS surface belongs to the D-related family shares the same CP lattice as the D surface. Its symmetries allow maintaining the self-complementary nature of the two hydraulic regions, when in the sheet form. Compared to the D surface, the FKS displays a higher topological complexity and a smoother curvature distribution, offering enhanced isotropy and diffusion uniformity within the pore network.

The Neovius topology is rarely adopted, but remains of interest due to its modular and periodic geometric structure, which could be exploited in microreactors or compact heat exchangers. In its sheet variant, it gives origin to non self-complementary channels, despite sharing the overall cubic symmetry with the P surface. From a morphologic standpoint, the Neovius surface shares the same BCC lattice as the P surface, and is therefore achiral.

The SplitP and Lidinoid structures have been analyzed in fewer studies.The Split-P topology generates fluid domains with significantly different shapes and volumes, posing challenges for heat-exchanger design where balanced flow distribution is required. This asymmetry arises from the partial breaking of the symmetry of the P surface, producing two morphologically distinct regions separated by a single continuous interface. When it is in the solid variant, the difference between the two regions require to chose among them which one should be printed as solid, whereas in the sheet variant it requires careful consideration. The Lidinoid lattice, instead, can be regarded as a non-chiral analogue of the Gyroid and yields two equivalent and spatially shifted channels. Interestingly, at certain porosities (above > 50%, also depending on the wall thickness), the Lidinoid sheet evolves from a bicontinuous to a tricontinuous topology, where a third disconnected fluid region emerges within the structure. This additional domain limits design flexibility and complicates manufacturing. Also, when this third region is not continuous, it may introduce isolated cavities that impede complete fluid percolation and uniform coating during fabrication processes.

Finally, topologies such as

FRD,

W-Type,

Koch, and

C, as well as some hybrid configurations, are reported only in isolated studies and are not included in

Table 4. These geometries have been primarily explored to assess their thermal performance in comparison to better-known TPMS types. While promising in certain cases, they do not yet offer a consolidated reference for design and optimization in heat transfer applications and fall outside the current focus of this investigation.

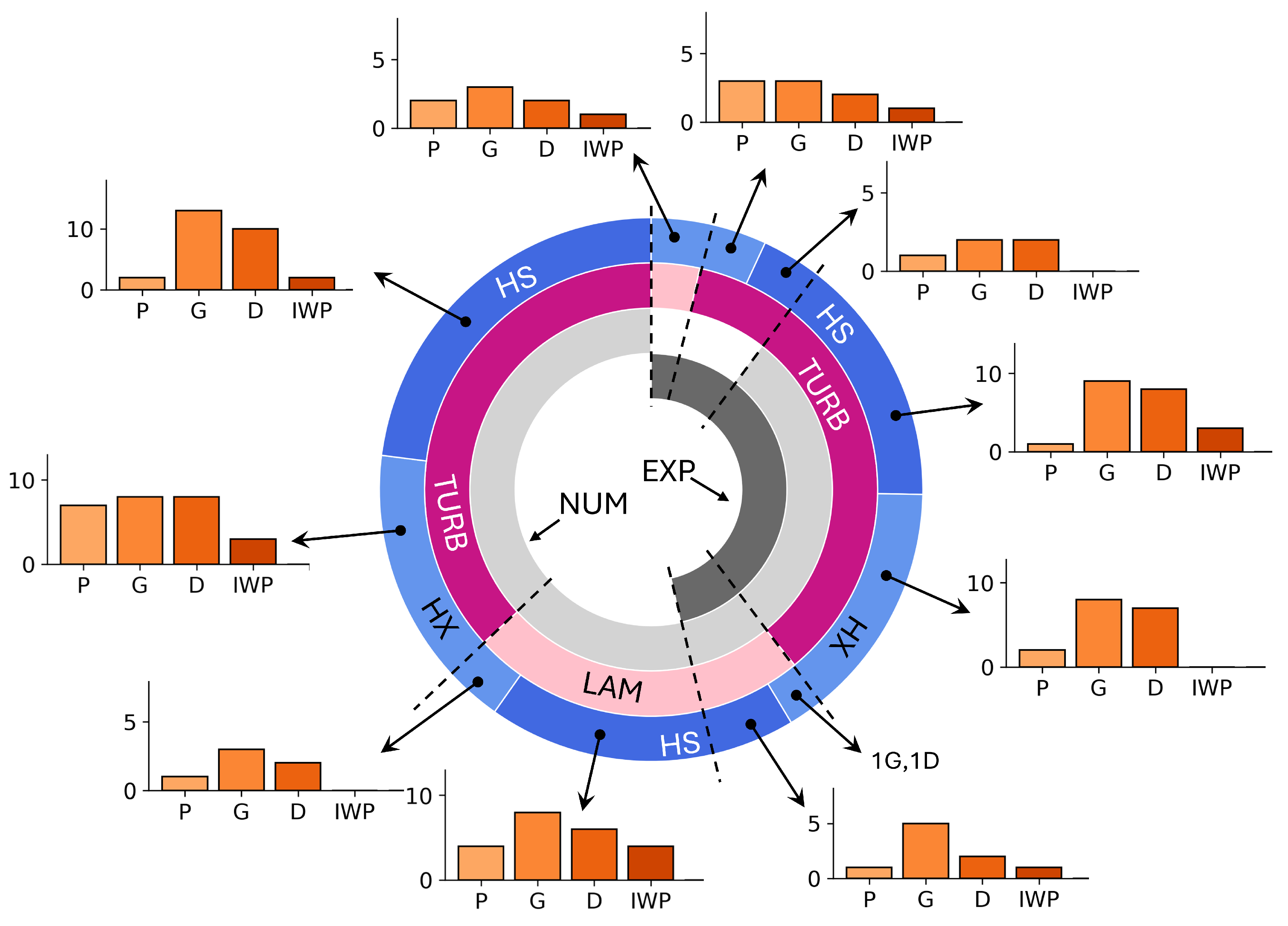

3.8. DI11: Flow Regime Investigated

The multi-ring donut chart of

Figure 10 provides an integrated view of the flow regime investigated (DI11) in the different papers, cross-linked with the focus of the study (DI5) and the specific application (DI4).

Most of the experimental studies focus on the turbulent regime, particularly for both HS and HX applications, with a strong emphasis on Gyroid and Diamond structures. Laminar flow conditions, on the other hand, are seldom explored experimentally, likely due to the need for more sensitive and precise instrumentation to capture low-velocity fields. From the numerical perspective, approximately 30% of the studies simulate laminar flows, mainly in the context of HS applications where Gyroid topologies are predominant. Turbulent flow remains the dominant regime overall, reflecting its relevance to industrial conditions, especially for HX. For the largest fraction of the HX studies, topologies with self-complementary channels are adopted, as expected. In the case of HS, the number of laminar and turbulent studies is more balanced, due to the growing interest in low-Reynolds applications such as microelectronics cooling [

38].

Note that each study in

Figure 10 can belong to more than one subcategory, according to its content. For instance, in [

64] HS are investigated, both numerically and experimentally, in the laminar and turbulent regimes, but the number of such examples is quite limited.

3.9. DI12: Turbulence Closures

For numerical studies, researchers are increasingly focusing on identifying the most suitable turbulence closure models for addressing the complex flow structures typical of TPMS geometries. The relationships between the adopted flow regime (DI11), simulation software (DI9), and turbulence models (DI12) are summarized in

Figure 11.

All turbulent simulations in the reviewed studies adopt Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) models for turbulence closure. No papers investigate Large Eddy Simulation (LES) or Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS).

The two-equation Standard k-ε model is a well-established and widely implemented RANS approach. Despite its widespread implementation in commercial and open-source CFD codes, it is used in a limited number of studies, mainly those employing Fluent, COMSOL, and Simerics-MP.

The

Realizable k-ε model, a refinement of the standard formulation, is designed to improve accuracy in flows with strong curvature, separation, or rotation [

193]. It is preferred by research groups using STAR-CCM+, where its numerical robustness is particularly appreciated. A single study also applies the

Lag Elliptic-Blending k-ε variant [

74], following promising performance previously observed in simplified geometries [

194].

The

Standard k-ω model, known for its improved near-wall resolution [

195], is used in few studies with Fluent, [

97,

124]. More commonly, the

k-ω SST (Shear Stress Transport) model [

196] is adopted, especially within Fluent-based investigations, due to its proven reliability in predicting separated flows.

Interestingly, the authors of [

83] report that in some test cases involving Gyroid and Diamond structures, the

Standard k-ε model provided better agreement with experimental data compared to the more advanced

k-ω SST formulation.

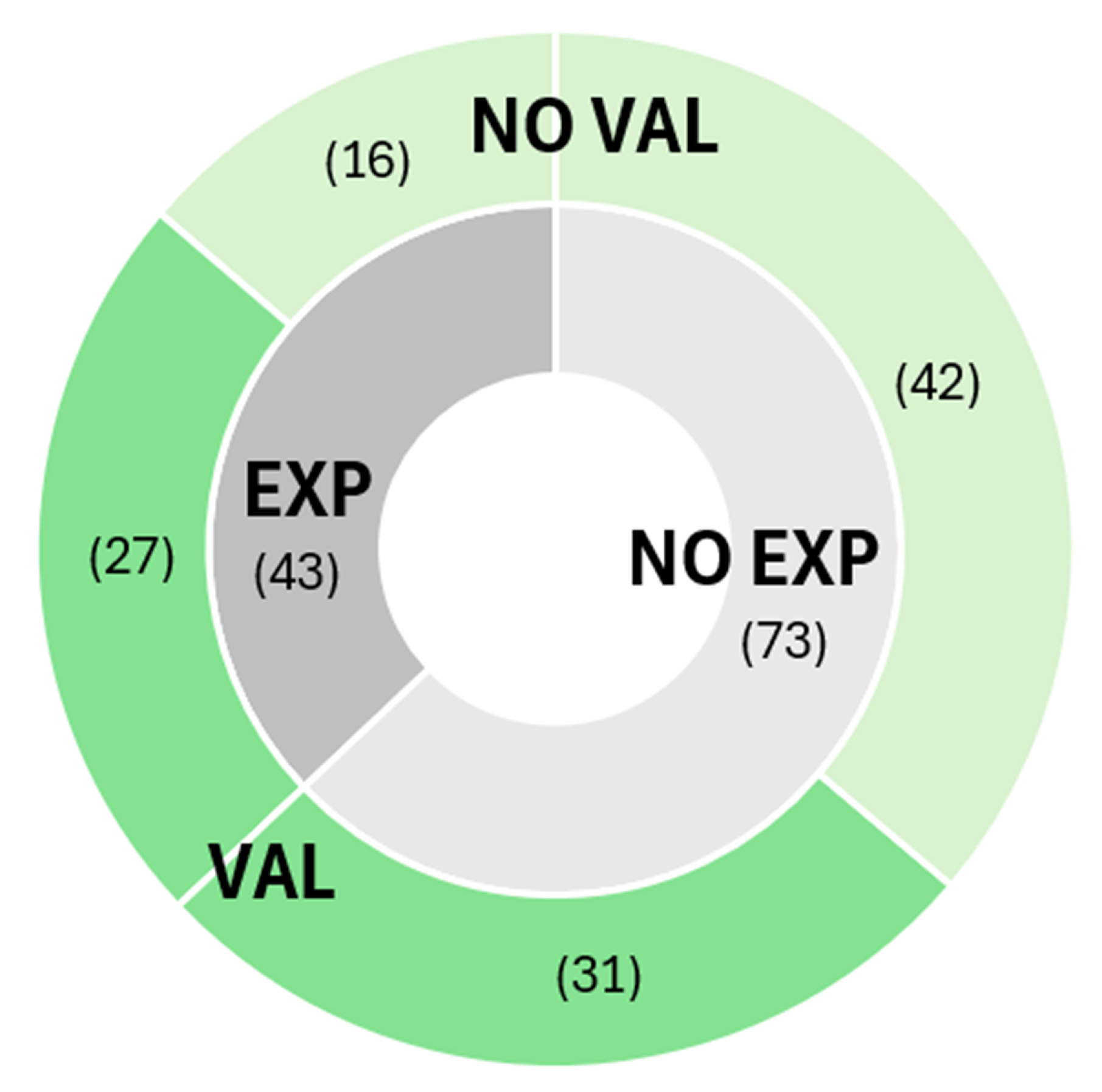

3.10. DI13: Validation of the Numerical Models

While solution verification, such as grid independence studies or uncertainty estimation via the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) method (as done, for example, in [

30]), is commonly reported in the analyzed studies, the validation of numerical models against experimental results is a less standardized practice.

To better quantify this aspect, the selected papers were classified based on whether they include original or external experimental data (EXP), and, if so, whether a direct comparison with the numerical results (i.e., a form of "validation") is provided, as summarized in

Figure 12.

Among the numerical studies considered, >40 also include experimental results, while the remaining are purely numerical (NO EXP). Within the first group (EXP), the majority present at least one comparison between simulated and measured data, either qualitative or quantitative, even if not always supported by uncertainty analysis or validation metrics. Surprisingly, a similar number of validations is also found among the studies that do not include new experimental work, but reference external data from the literature. Therefore, while formal validation procedures remain relatively rare, approximately half of all numerical studies include some form of comparison with experimental results. This underlines the growing, but still incomplete, effort to anchor simulations to physical measurements, whether obtained by the same authors or retrieved from existing benchmarks.

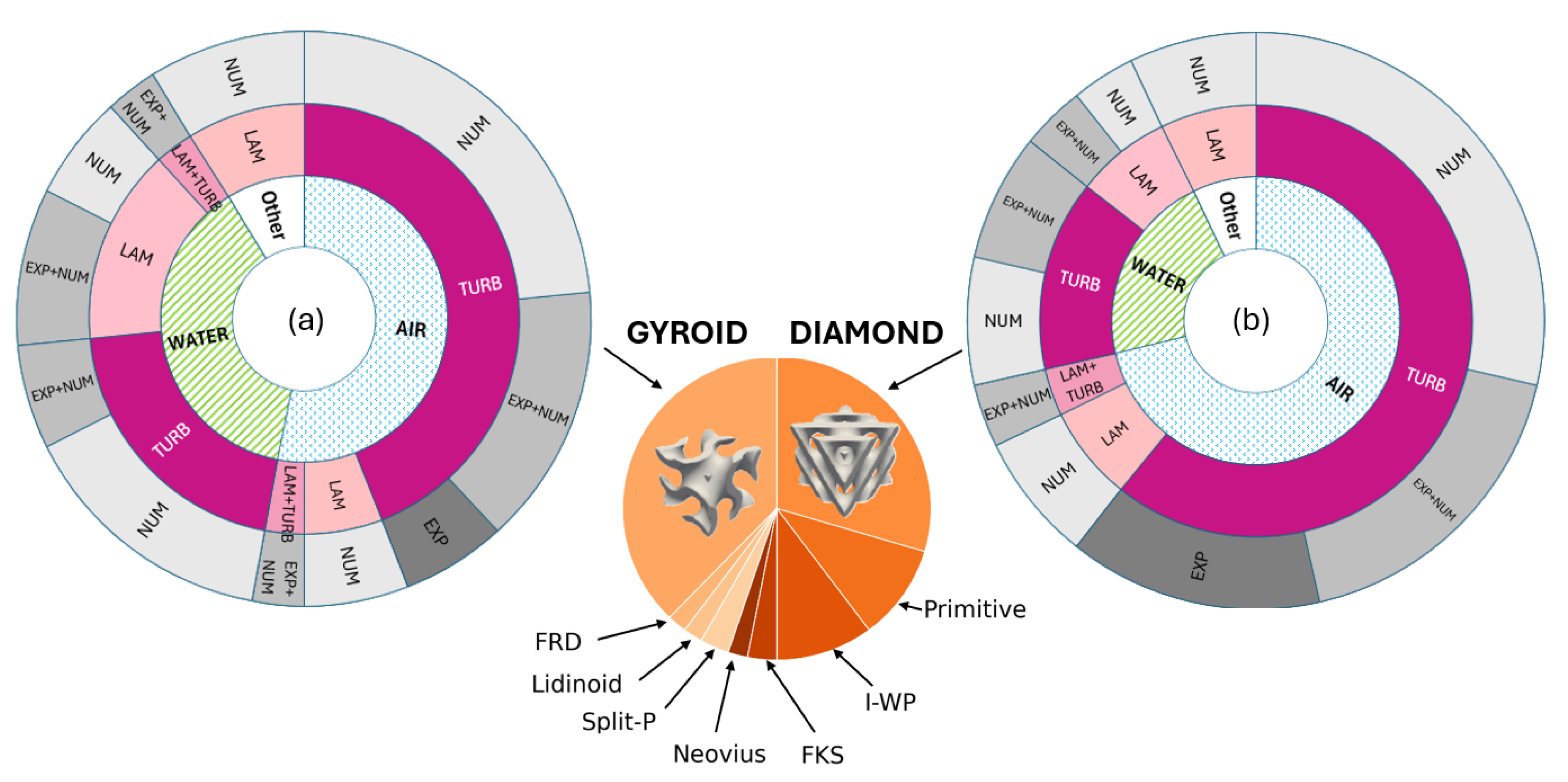

4. Use of the S-DB to Analyse Gyroid and Diamond HS and HX

4.1. Studies on Heat Sinks

The publications dealing with HS applications are synthesized in

Figure 13. The central pie chart reports the share of the different TPMS topologies adopted as heat sinks (DI10), highlighting the dominance of Gyroid and Diamond structures. The two sunburst plots on the sides provide additional insight for these two topologies by resolving, for each working fluid (DI7), the flow regime (DI11) and the type of study (DI5). In combination with the detailed information reported in

Table 5 and

Table 6, this figure shows that most HS-oriented investigations rely on air-cooled devices operating in turbulent conditions and are primarily based on numerical simulations, with experimental work limited to a smaller number of contributions.

In the following, we do not aim at an exhaustive description of the thermal performance reported in each contribution, which would be hardly comparable because of the different operating ranges and performance indicators adopted. Instead, we emphasise, for each cluster of studies, the most relevant geometrical choices, modelling strategies and performance metrics that will be critically discussed in

Section 5 with the goal of identifying robust trends and current gaps in the literature.

4.1.1. Gyroids with Air as the Working Fluid

As already anticipated by

Figure 13a, Gyroid-based heat sinks cooled by air constitute the most extensively explored configuration, and their main features are summarised in

Table 5. The body of work can be broadly grouped into (i) laminar studies on idealised or customised lattices, often with a strong geometrical-design flavour, and (ii) turbulent studies on more application-oriented channels, where attention is shifted towards manufacturability and system-level performance.

Only two contributions address purely laminar air flow through Gyroid structures, both by means of numerical simulations [

40,

57]. In [

40], recognising the enhanced mixing promoted by TPMS, a two-dimensional lattice of polygons is mapped onto a Gyroid sheet surface, thus generating a surface tessellation. The study explores the effect of polygon shape and size on the flow and heat transfer in pipes filled with such structures for

. In [

57], a design-oriented methodology is proposed to customise solid TPMS (Gyroid, Diamond, I-WP and Primitive) over a wide porosity range (0.2–0.8), using a domain consisting of a row of eight lattice cells and Reynolds numbers from 10 to about 130. The thermal–hydraulic performance is compared using the ratio between the Colburn and friction factors (referred to by the authors as an “area goodness factor”), and the I-WP lattice is identified as the best performing topology under the investigated laminar conditions. Interestingly, while the lattice is clearly identified as a porous-medium, that could hint to a Darcy–Forchheimer framework as done, for instance, in [

197], the heat-transfer analysis relies on classical Nusselt-type correlations. This sort of internal inconsistency between momentum and heat-transfer models will be revisited in

Section 5.

A mixed laminar–turbulent configuration is examined in [

129], where sheet Gyroid, Diamond and I-WP lattices with identical cell size and thickness are 3D-printed as four cells in a row on a heated surface. The study couples experiments and simulations across a Reynolds-number range spanning both regimes, and includes a comparison between numerical and measured pressure-drop data for the Gyroid case. Based on their analysis, the authors conclude that the Diamond lattice achieves the highest convective heat-transfer performance. However, the influence of entry-region effects and the streamwise extent required to reach fully developed flow are not systematically assessed.

When these two contributions are considered together, a clear discrepancy emerges. Under comparable Reynolds-number ranges and using nominally similar metrics, [

57] reports the I-WP lattice as the most effective topology, while [

129] identifies the Diamond lattice as the superior performer. These conflicting conclusions stem from several factors: (i) the adoption of different perfoemance metrics, which are not standardised for TPMS and may emphasise different aspects of the thermal–hydraulic response; (ii) differing levels of experimental benchmarking and numerical model validation; and (iii) variations in the treatment of developing-flow regions, which are known to affect both Nusselt number estimates and friction factors. This lack of methodological uniformity across studies makes it difficult to derive robust rankings of TPMS topologies and underscores the need for harmonised evaluation practices, as discussed in

Section 5.

The majority of studies on air-cooled Gyroid HS focuses on turbulent flow and is dominated by channel configurations containing a limited number of unit cells. A numerical work in this direction is [

36], where Gyroid solid and sheet lattices arranged as

cells are inserted in a square channel heated on all sides. The Gyroid sheet provides the highest heat transfer coefficient at the expense of a substantial pressure drop, and the feasibility of 3D printing and graded lattices is discussed. Building on the concept of grading and mapping, the topology–optimisation study [

100] compares graded and uniform Gyroid and Diamond lattices (both sheet and solid) in a one-side heated square channel containing a

lattice region. Based solely on the CFD results, the Diamond-sheet configuration is reported as providing the most favourable balance between heat-transfer enhancement and pressure loss. However, these numerically-derived conclusions do not fully align with available experimental evidence. In particular, the campaign presented in [

145], conducted in a comparable Reynolds-number range (

–1000), shows that the Gyroid-sheet lattice exhibits a higher ratio of the Chilton–Colburn factor to the friction factor than the Diamond-sheet lattice. This divergence highlights a broader issue already observed in the literature: the performance assessment of TPMS structures relies on heterogeneous and often non-equivalent evaluation criteria, which are not yet standardised for porous-like architectures.

Several works further explore the thermal-hydraulic behaviour of Gyroid heat sinks in similar square-channel arrangements, often using four to five cells in the streamwise direction and adopting different RANS closures. For instance, [

83] investigates Gyroid sheet and solid lattices, along with a Diamond-solid configuration, in the range

, and compares experimental and numerical pressure drops. Good agreement is obtained when the Realizable

k–

model is employed, and performance is ranked using the PEC proposed in [

198] at fixed pumping power, which leads to the Diamond solid lattice being identified as the most efficient solution. The suitability and practical implementation of such a PEC for TPMS lattices, however, are not straightforward, as they require a consistent definition of an equivalent smooth channel and of the characteristic velocity; this aspect will be addressed in the general discussion.

On the experimental side, [

105] and [

145] provide important turbulent-flow benchmarks for air-cooled Gyroid heat sinks. In [

105], Gyroid-sheet and Diamond-sheet lattices manufactured from polymer and subject to volumetric heating are tested for

. Local measurements indicate that the Nusselt number remains almost constant along the streamwise direction, suggesting that reliable average correlations can be formulated. In [

145], aluminium Gyroid, Diamond and Primitive sheet lattices (including hybrid combinations) are tested, and the measured porosity is found to be lower than the CAD value, emphasising the impact of manufacturing on the effective geometric parameters. Among the tested topologies, the Gyroid exhibits the lowest pressure drop.

A number of recent numerical studies exploit these experimental datasets to assess turbulence models and to explore more advanced geometric modifications. Examples include the comparison between plane Gyroid-sheet lattices and variants equipped with surface fins [

128], and the investigation of cell-size effects for different porosities and materials [

119]. Other works introduce controlled deformations of the Gyroid surface [

44,

130] or more peculiar modifications and alternative TPMS such as SplitP and Lidinoid [

45]. In all these contributions, the

k–

SST model is typically adopted and validated against a subset of experimental cases, with varying levels of agreement, which again points to the need for a more systematic model assessment.

Finally, some studies depart from the standard straight-channel geometry and address configurations closer to technological applications. For example, wedge-shaped channels representative of turbine blade cooling are analysed in [

150], where Gyroid, Diamond and I-WP sheet and solid lattices are compared over

. The Diamond sheet is reported to provide the best trade-off between heat transfer enhancement and pressure loss relative to pin-fin baselines, and the impingement and mixing induced by Gyroid and Diamond sheets are highlighted as the main mechanisms controlling the heat transfer. The influence of lattice rotation around an axis normal to the heated surface is explored in [

159] using a reduced computational domain, and the resulting PEC (again based on [

198]) is shown to be highly sensitive to the rotation angle, which is proposed as a practical design knob. The rotation of the lattice is claimed as a good trick to tailor the structure efficiency to the needed value. Note, however, that a complete rotation in 3D, also involving the axis parallel to the heated surfaces has not been addressed so far, and deserves attention.

Overall, the literature on Gyroid heat sinks with air reveals a number of recurring features: simulations are often confined to short lattice rows, with limited discussion of entrance effects and of the establishment of fully developed conditions; different definitions of Reynolds number and characteristic velocity are adopted; and a variety of performance indicators (in particular, different implementations of PEC) are used. These aspects, together with the porous-medium analogy and the choice of turbulence models, are revisited and critically assessed in

Section 5.

4.1.2. Gyroids with Water as the Working Fluid

Studies employing water as the working fluid display a wider variety of operating conditions than those based on air, and several contributions explicitly include laminar configurations. A representative example is [

79], where a square channel containing two unit cells in a row is analysed with one heated wall. Both Gyroid-sheet and Diamond-sheet lattices are considered, together with a progressive stretching of the cells along the flow direction. The stretching reduces the pressure drop with only a mild penalty on heat transfer. The performance ranking is again expressed through the PEC, and the Diamond-sheet lattice emerges as the most efficient solution in the tested range.

A full-scale HS configuration is analysed in [

38], where a single layer of Gyroid-sheet cells is used for microprocessor cooling. Different porosities and loading conditions are explored, and the comparison with pin-based geometries highlights the advantages associated with the TPMS-enhanced mixing. A similar problem is addressed in [

54] through both experiments and simulations, with comparable conclusions. Further considerations on electronics cooling are discussed in [

88], which focuses on graded Gyroid-solid and Diamond-solid lattices. The proposed structures are shown to provide a viable alternative to straight channels by combining mixing enhancement and acceptable pressure losses.

Another important application is reported in [

60], dealing with the optimisation of a cold-plate configuration. Here, a Gyroid lattice with trimmed thickness is used to guide the flow through a U-shaped path. A parametric study on key geometrical variables enables the identification of an optimised configuration that outperforms a serpentine cooling strategy in terms of heat transfer.

More recent literature extends the adoption of TPMS to cooling strategies for high-heat-flux components in nuclear fusion systems. In [

74], Gyroid-sheet, Gyroid-solid and SplitP-sheet metallic structures are proposed for the cooling of mirrors in the microwave transmission lines for the plasma heating. All examined topologies are shown to satisfy the design constraints. In [

108], a Gyroid-sheet lattice is used to design a divertor tile for the Wendelstein 7-X stellarator, withstanding heat loads up to

.

A more fundamental perspective on the thermal transport mechanisms is given in [

116], which compares, experimentally and numerically, a metal foam and a Gyroid-sheet lattice as porous cooling media. The Gyroid structure exhibits a consistently higher PEC, thus pointing towards a more favourable interplay between mixing and pressure losses. The same research group extends the analysis in [

117], introducing an impinging-jet cooling configuration and exploring different lattice porosities. The effect of cell size and porosity is further investigated in [

64] using the same experimental setup.

Beyond these canonical geometries, the work in [

88] evaluates the thermal-hydraulic performance of several TPMS, including Gyroid, Diamond, Primitive and the more unconventional FRD topology. The authors propose a useful representation of the performance in the

plane, where

is a pressure-drop coefficient. This two-parameter space allows a straightforward visual selection of the most suitable topology for a given application. In analogy to the recursive Gyroid studied for air in [

47], the analysis in [

46] shows that recursive configurations may help alleviate the pressure-drop penalty typically associated with TPMS.

As a final remark, two additional contributions mostly devoted to structural optimisation, [

101] and [

139], are not included in

Figure 13a. These works rely on idealised, non-heated, or highly reduced domains and therefore fall outside the scope of this subsection.

4.1.3. Diamonds with Air and Water as the Working Fluids

The sunburst plot in

Figure 13b shows that most Diamond-based HS studies involve air-cooled devices operating in turbulent conditions. Four contributions are purely experimental, whereas several other works combine numerical simulations and test data, enabling an assessment of the modelling accuracy (see

Table 6).

Beyond the studies already mentioned in

Section 4.1, an interesting application domain is found in Concentrated Solar Power receivers. In [

103], small stainless-steel samples equipped with Diamond-sheet and SplitP-sheet lattices are tested in a solar simulator. Both TPMS exhibit excellent heat removal capabilities, with the SplitP-sheet providing the best overall performance.

The concept of employing TPMS as porous cooling media is investigated experimentally in [

51], focusing on “transpiration cooling” for gas-turbine hot-gas-path components. A Diamond-solid lattice is used as the porous insert, and the emerging cooling film generated by the coolant percolating through the structure provides effective thermal protection. For completeness, we note that Gyroid lattices have also been explored as porous cooling media in [

50], where the cooling efficiency is shown to depend strongly on porosity at fixed blowing rate. A related configuration, termed “effusion cooling”, is analysed in [

152] and [

153]. Numerical results indicate that Diamond-based TPMS yield a more uniform flow distribution and lower thermal stresses compared to pin-based solutions. Further optimisation of the same design, primarily through the removal of lattice material near the outlets, is presented in [

153].

Other numerical studies aim at investigating the fundamental thermal-hydraulic behaviour of Diamond lattices. In [

42], seven Diamond-sheet cells are placed in a square channel heated on one side. The cell size is kept constant, whereas the porosity is varied by changing the wall thickness. The results show that the wall-thickness effect on heat transfer is negligible for

, but the associated decrease in porosity leads to a substantial reduction in PEC under laminar conditions. A larger computational domain, consisting of ten consecutive cells, is used in [

141] to compare the thermal-hydraulic performance of several TPMS, including Diamond-solid, Gyroid-solid, Lidinoid-solid, Primitive-solid and Neovius-solid. In this extensive comparison, the Diamond lattice consistently displays the best performance.

The combined experimental-numerical study [

143] investigates Diamond-solid lattices subjected to controlled geometric stretching. By compressing or elongating the lattice in directions parallel or orthogonal to the flow, the authors identify deformation configurations capable of reducing the pressure drop while enhancing the overall PEC. A similar mixed approach is adopted in [

144], which analyses Diamond-sheet and Diamond-solid lattices. The numerical simulations rely on a

-cell domain embedded in a one-side-heated square channel under turbulent flow. The ranking based on PEC identifies the Diamond-sheet as the most efficient configuration. The study also highlights the importance of manufacturing tolerances, which significantly affect porosity and local wall thickness.

A further contribution is offered by [

121], where a novel metric is introduced to quantify the effective heat penetration into the fluid. The metric is defined as the ratio between the cross-sectional area having a dimensionless temperature greater than

of the reference wall temperature, and the total area. This indicator allows an alternative assessment of the effect of introducing Diamond-sheet TPMS into a heat sink, particularly relevant at high Biot numbers where convective transport dominates. However, the metric does not account for the pressure-drop penalty and therefore should be considered complementary to more conventional thermal-hydraulic figures of merit. The authors note that hybrid solutions, combining TPMS with more traditional cooling elements, may be advantageous at low Biot numbers.

Overall, the Diamond-based HS literature reveals a consistent pattern: strong reliance on turbulent-air studies, frequent use of short lattice rows, significant sensitivity of the performance to porosity and manufacturing deviations, and a variety of performance metrics that complicate cross-study comparisons. These recurring aspects will be reconsidered in the broader analysis of

Section 5.

4.2. Studies on Heat Exchangers

A summary of the studies performed on heat exchangers equipped with TPMS is reported in

Figure 14. The pie chart highlights that, although Gyroid and Diamond remain the most common choices, also non-self-complementary topologies such as Neovius, SplitP and I-WP have been explored for HX applications (although only in a limited number of studies). The accompanying sunburst plots further resolve, for Gyroid and Diamond lattices, the working fluids employed (DI7), the flow regimes (DI11), and the type of study (DI5).

Gyroids dominate the literature on TPMS-based HX (

Table 7), followed by Diamond lattices (

Table 8). Most studies investigate water-to-water configurations, often with one stream on each side of the TPMS core. A number of contributions also propose correlations for the Nusselt number or performance comparisons against conventional HX types.

The authors of [

79] explicitly address the lack of detailed heat-transfer characterisation in TPMS HX. Their work presents an experimental campaign on a counter-flow HX 3D-printed in AISI 316L. By combining measurements from both hot and cold sides, they derive a Nusselt-number correlation for single-phase water flow. A complementary configuration is studied in [

61], where a cross-flow HX printed in resin enables wall thicknesses below

and laminar-flow testing. The Gyroid-based HX demonstrates higher efficiency at fixed NTU values than a broad set of compact and non-compact HX. A further Nu correlation is proposed in [

146] for another Gyroid-based cross-flow HX, combining experiments and numerical simulations.

A purely numerical comparison of several TPMS (Gyroid, Diamond, Primitive, Neovius, FRD and FKS) is conducted in [

80]. Simulations are performed on a

unit-cell domain, periodic in the transverse direction, and for different unit-cell sizes. In laminar flow, the Diamond-based HX achieves heat-transfer levels comparable to tubular HX while occupying an order-of-magnitude smaller volume, highlighting the compactness benefits of TPMS.

Most other water-water studies consider the entire HX component, rather than isolated cells. In [

87], a counter-flow Gyroid HX is characterised numerically and experimentally. Among the tested RANS models, the

k–

SST closure shows the best agreement with experiments. The numerical analysis indicates that heat transfer scales approximately linearly with the inverse of the cell size, whereas the pressure drop increases more steeply. An evaluation of entropy generation is also provided, emphasising the trade-off between compactness and pressure losses. The authors stress the relevance of customisation and compactness when justifying the use of TPMS in HX.

In [

53], a single Gyroid cell is investigated in counter-current air-air operation for

, primarily assessing the effect of wall thickness. The study [

95] extends this approach by experimentally and numerically analysing three cross-flow metal HX using Primitive, Gyroid and Diamond lattices. All prototypes exhibit good dimensional accuracy and structural integrity. The Diamond lattice provides the highest efficiency with a lower pressure drop than the other topologies. Follow-up work by the same group, [

50], investigates different Diamond cell sizes and confirms that HX effectiveness increases as cell size decreases.

Diamond-based HX are also confirmed to offer superior performance in [

122]. The study includes an optimisation of the lattice regions near the manifolds to reduce pressure losses. Similarly, [

115] compares Diamond-based HX to plate HX via simulations and tests, and investigates alternative manifold geometries, targeting pressure-drop reduction with minimal impact on heat transfer.

The numerical comparison of Gyroid, Diamond and SplitP lattices in [

96] shows that wall thickness, lattice unit length and material conductivity have a significant impact on heat transfer. The numerical results for Gyroid lattices exhibit excellent agreement with measurements from an aluminium HX. The achieved heat-transfer coefficient is much higher than that of a commercial compact HX of comparable power.

Ultra-compact Diamond HX are analysed experimentally and numerically in [

75] and [

76]. The first work compares TPMS HX manufactured in different materials against a plate HX, showing again substantial gains in volumetric heat-transfer coefficient for the TPMS designs. The numerical results confirm that Diamond lattices promote more uniform temperature and velocity fields. The second work examines different Diamond cell sizes and reports that the manufactured wall thicknesses (via SLM) exceed the design values by over 25%, which significantly affects both pressure drop and heat transfer. Note, however, that the numerical simulation of TPMS with rough surfaces remains a challenge.

Three additional studies provide combined numerical-experimental investigations of full HX prototypes: [

97,

104,

142]. These works highlight the feasibility of lattice grading in practical HX design and the beneficial effect of abrasive-jet cleaning on pressure drop when metallic TPMS are used.

A number of contributions focus on purely numerical analyses of cross-flow HX with different TPMS. In [

37], the efficiency-NTU values of Gyroid- and Primitive-based HX are compared to theoretical cross-flow correlations. TPMS HX are shown to achieve significantly higher efficiencies, and at fixed NTU the Primitive lattice outperforms the Gyroid. The general applicability of the effectiveness-NTU method to TPMS with complex internal flows is demonstrated in [

10] for a Diamond-based air-to-air HX operating in turbulent regime. The study [

99] additionally considers hybrid Gyroid-Diamond configurations. Although Gyroid lattices yield the most favourable Nusselt-number distribution, some hybrid solutions show potential to surpass the baseline topologies.

Finally,

Table 7 also includes the topology optimisation analysis presented in [

81], which relies on analytical shape functions rather than discretised flow equations. This work illustrates how the mathematical structure of TPMS can be used directly for optimisation purposes, without requiring the full numerical resolution of the governing equations.

5. Discussion and Research Outlook

This work provides the first systematic and reproducible assessment of Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces for thermal management, covering heat transfer applications over a 25-year period and using the APISSER methodology to ensure transparency in paper identification, screening and data extraction. The present study analyses a large body of literature, with nearly fifty HS papers adopting Gyroid and Diamond lattices and almost thirty HX studies. This extended coverage provides a more comprehensive perspective on the state of the art and enables trends that were previously difficult to discern in previous reviews. The objective methodology used for the paper identification also allowed pointing out the presence of "false negative" papers, excluded from the database mainly because of lack of evidence of the key words of the present analysis. This finding suggests more care in the title and abstract phrasing for future papers on the topic.

A first observation on the papers extracted from the database concerns the dominance of numerical studies. CFD is the primary modelling tool across all applications, and turbulent flows are almost always analysed through RANS closures, especially the k– SST and Realizable k– models. While these models often provide reasonable global predictions, detailed validation remains limited. Experimental datasets are scarce and, when available, are generally used only for partial comparisons. Verification and validation practices, including uncertainty quantification and standardized procedures sucha s the ASME V&V one, are seldom adopted. In addition, most simulations employ short computational domains (typically four or five unit cells), resulting in limited control of entrance effects and the onset of fully developed flow, an aspect that directly affects the accuracy of derived Nusselt and friction-factor correlations. Moreover, given the geometric complexity of TPMS and the presence of strong mixing and curvature-driven flow structures, RANS closures may not always capture the relevant physics. Targeted LES or DNS studies on limited domains (one or two unit cells) could provide valuable reference data for model calibration. Similarly, there is a need for experimental campaigns providing spatially resolved heat-transfer and pressure fields to support reproducible validation.