1. Introduction

Jets are fluid streams formed by the discharge of fluid through an orifice or nozzle into a surrounding medium, resulting in a momentum-driven flow that entrains and interacts with the ambient fluid. Due to their ability to deliver high momentum fluid, jets are widely employed in practical applications across various engineering domains (

Figure 1). They play a pivotal role in propulsion systems including aircraft engines, rocket propulsion, and marine thrusters (

Figure 1a) where high velocity fluid ejection generates thrust [

1]. Jets are also extensively used in heat and mass transfer applications, such as impinging jets for localized cooling, spray cooling in electronics, and industrial drying processes (

Figure 1b), where enhanced convective transport is critical [

2]. Additionally, they are used in flow control and mixing to improve combustion efficiency, reduce noise, and mitigate pollution (

Figure 1c) by actively manipulating flow fields and enhancing fluid mixing [

3,

4,

5].

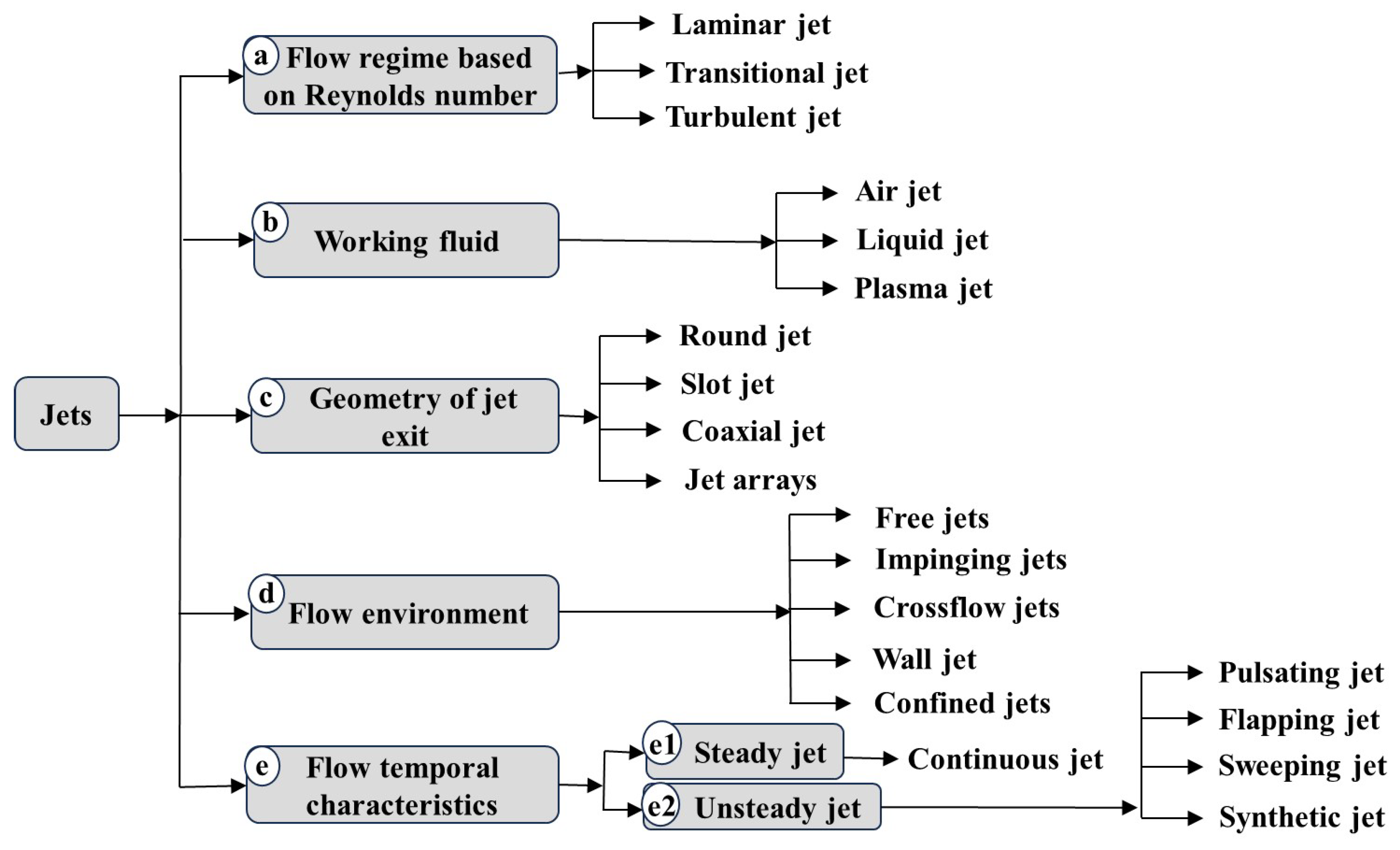

Jets can be broadly classified based on different criteria, as shown in

Figure 2. Depending on the flow regime, jets can be classified as laminar, transitional, or turbulent, with each regime distinguished primarily by the Reynolds number (

Figure 2a). Laminar jets exhibit smooth flow [

6,

7], transitional jets show emerging instabilities [

8], and turbulent jets display chaotic motion with strong mixing [

9,

10]. Classifications based on working fluid (

Figure 2b) are air jets [

11], liquid jets [

12], and plasma jets [

13]. Each type varies in fluid properties and energy requirements, influencing their suitability for specific thermal and flow control applications. Jet classification based on exit geometry (

Figure 2c) includes round jets [

14], slot jets [

15], coaxial jets [

16], and jet arrays [

17]. Each geometry produces distinct flow patterns and spatial coverage, affecting mixing efficiency and heat transfer characteristics. Jets, based on the surrounding flow environment (

Figure 2d), can also be categorized into free jets [

18], impinging jets [

19], crossflow jets [

20], wall jets [

21], and confined jets [

22]. These categories reflect differences in boundary interactions and flow confinement, which significantly influence jet behavior and performance. Additionally, jets based on their temporal characteristics (

Figure 2e) can be classified as steady jets maintaining continuous flow (

Figure 2e1) [

18] and unsteady jets (

Figure 2e2). The latter includes pulsating [

23], flapping [

24], sweeping [

25], and synthetic jets (SJs) [

26]. Steady jets provide consistent flow conditions, while unsteady jets exhibit time-varying dynamics that enhance mixing and flow control capabilities [

27].

Among unsteady jets, synthetic jets are unique in generating periodic vortices through alternating suction and blowing without net mass input [

26]. Their compact design [

19], non-requirement of external fluid to form the jet [

26], precise control over operating parameters [

16], energy efficiency [

28], and easy integration into complex circuits [

29] make synthetic jets well-suited for a wide range of engineering applications.

Figure 2.

Jet classification based on various criteria.

Figure 2.

Jet classification based on various criteria.

1.1. Overview of Synthetic Jets

Over the last two decades, SJs, also referred to as zero-net-mass-flux (ZNMF) actuators [

26], have gained significant attention as an innovative approach in the fields of fluid mechanics [

30,

31] and aerodynamics [

32,

33]. Unlike conventional jet systems that rely on mechanical components such as rotors or blades, SJs operate without any physically moving parts, eliminating issues related to wear and tear [

34]. This inherent characteristic enhances their reliability and extends their operational lifespan compared to traditional mechanical systems [

28].

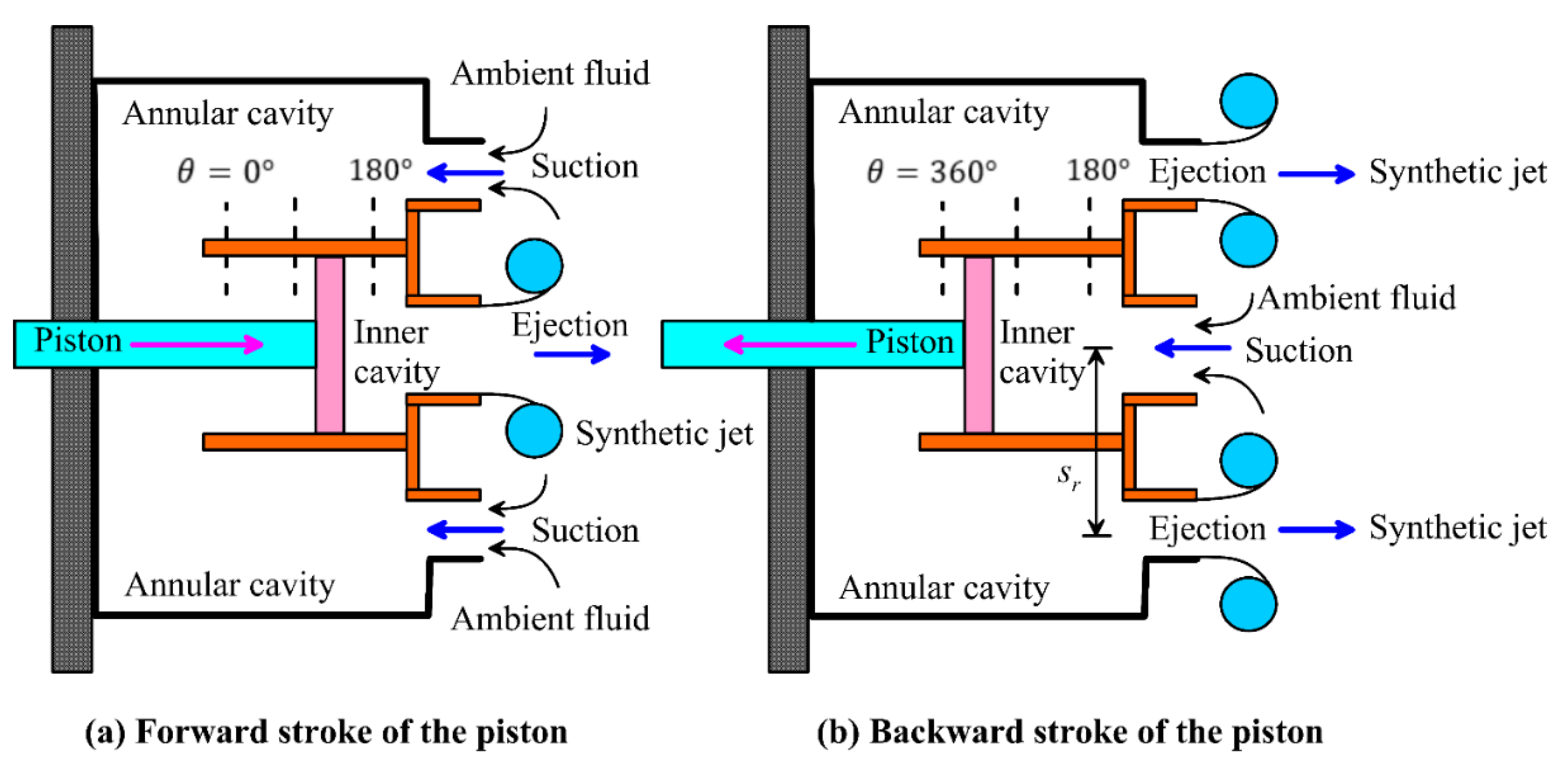

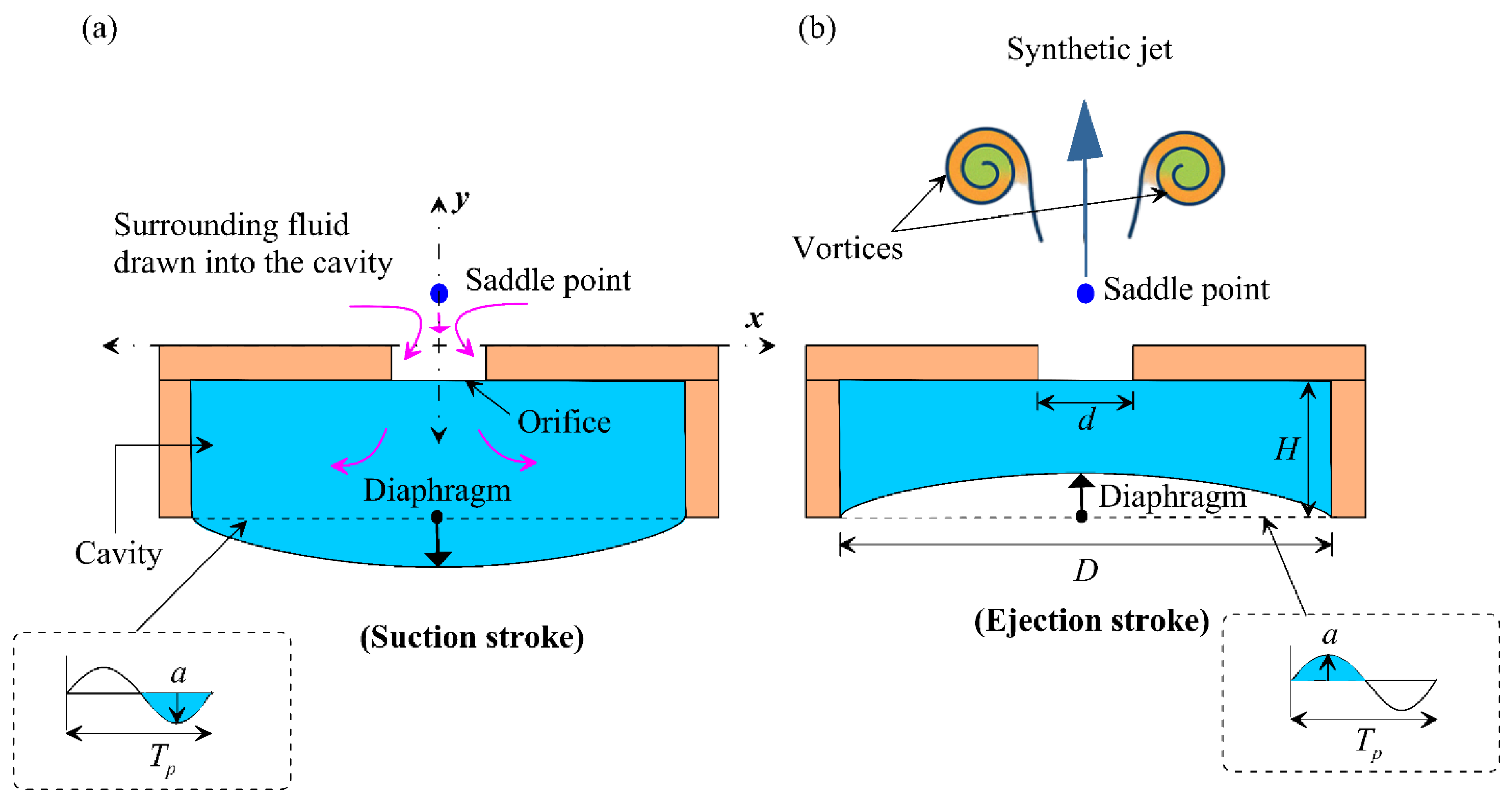

Synthetic jets are typically generated using a fluidic device called a synthetic jet actuator (SJA) (

Figure 3), which consists of a cavity enclosed by a vibrating membrane on one side and an orifice on the other [

26]. The vibrating medium can be a piston-cylinder arrangement [

35], a speaker [

36], or a diaphragm [

16]. When an alternating current (AC) is applied, the diaphragm undergoes oscillatory motion, drawing surrounding fluid into the cavity during the suction stroke (

Figure 3a) and ejecting fluid along with a pair of counter rotating vortices during the ejection stroke (

Figure 3b). This cyclic process generates a series of vortex rings, which collectively form the synthetic jet [

37]. Typically, the ejection phase produces a high velocity jet that dominates the region downstream of the orifice, while the suction phase induces inward flow toward the orifice. These opposing phases create distinct flow regions, with a saddle point often observed near the orifice exit, separating the suction-influenced zone from the ejection-dominated region (

Figure 3). The resulting SJs exhibit high-momentum [

38] and turbulent characteristics [

29].

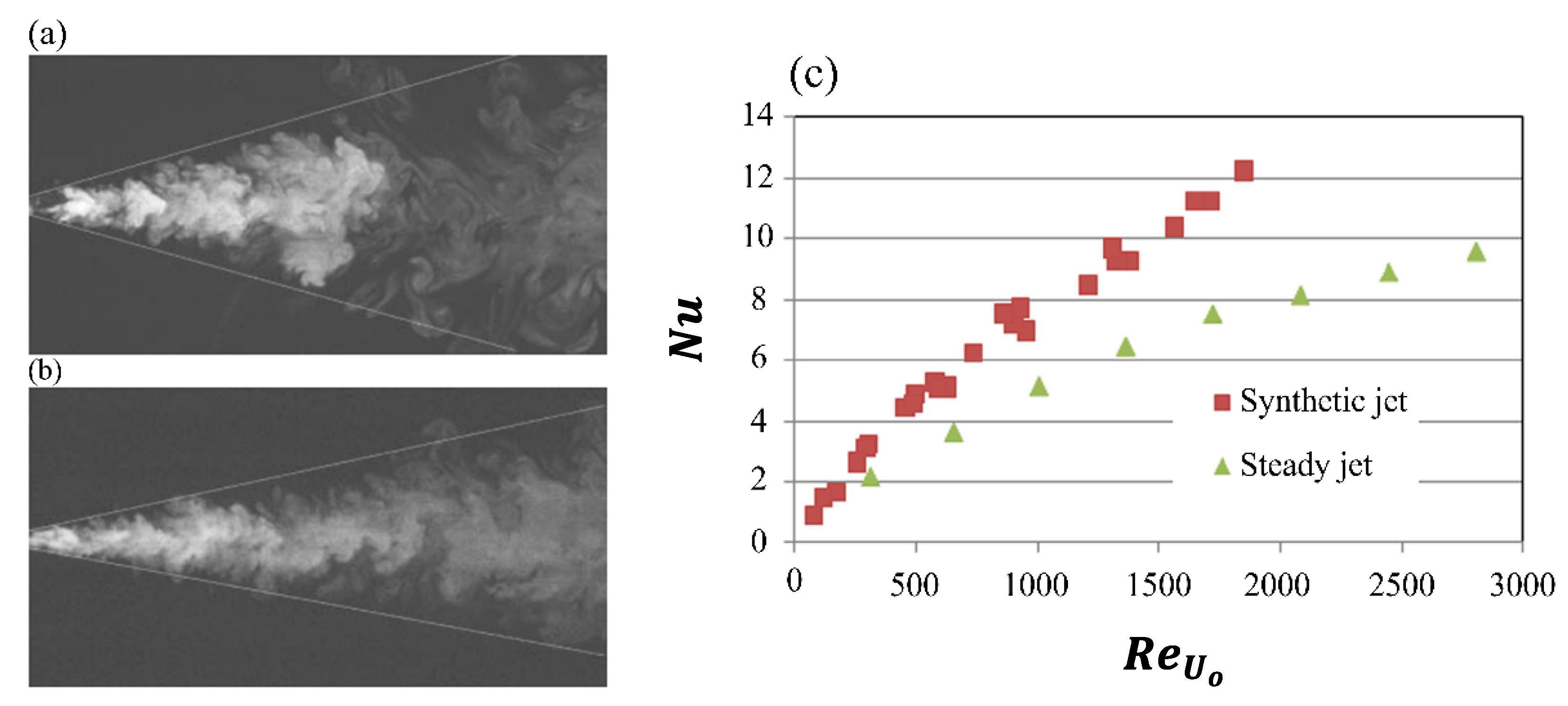

1.2. Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Jets and Continuous Jets

Unlike continuous jets (CJs), which require an external fluid source, SJAs utilize the surrounding fluid, eliminating the need for additional airflow [

29]. For a given Reynolds number (

Re), synthetic jets exhibit stronger entrainment of the surrounding fluid [

18,

29], leading to a wider and more rapidly spreading jet (

Figure 4a) compared to continuous jets (

Figure 4b). Hot-wire anemometry and Schlieren visualizations confirm that these vortex structures dominate the early development of SJs before transitioning into turbulence downstream [

26,

39]. Under identical operating conditions, SJs generate approximately 1.414 times higher eddy viscosity than CJs, promoting stronger momentum transfer and enhanced mixing due to their pulsatile nature [

27].

In terms of thermal performance, SJs produce broader and more uniform thermal distributions during impingement cooling. Under identical flow conditions (

≈ 1700), the Nusselt number for SJs exceeded that of CJs by approximately 34% (

Figure 4c), with the improvement attributed to the dynamic entrainment and mixing characteristics of jets [

40]. The enhancement in Nusselt number remains significant across a range of

[

41]. Additional studies support these findings, consistently demonstrating improved convective cooling by SJs relative to CJs under similar operational regimes [

42,

43]. The enhanced entrainment and increased eddy viscosity make synthetic jets a compelling alternative to continuous jets.

Figure 4.

Evolution of synthetic and continuous jets along with their heat transfer characteristics. Flow development of (a) synthetic jets and (b) continuous jets, reproduced with permission from [

18]; (c) variation of Nusselt number with Reynolds number at a jet-to-heated-plate distance of

Y = 10 for both jet types, reproduced with permission from [

40].

Figure 4.

Evolution of synthetic and continuous jets along with their heat transfer characteristics. Flow development of (a) synthetic jets and (b) continuous jets, reproduced with permission from [

18]; (c) variation of Nusselt number with Reynolds number at a jet-to-heated-plate distance of

Y = 10 for both jet types, reproduced with permission from [

40].

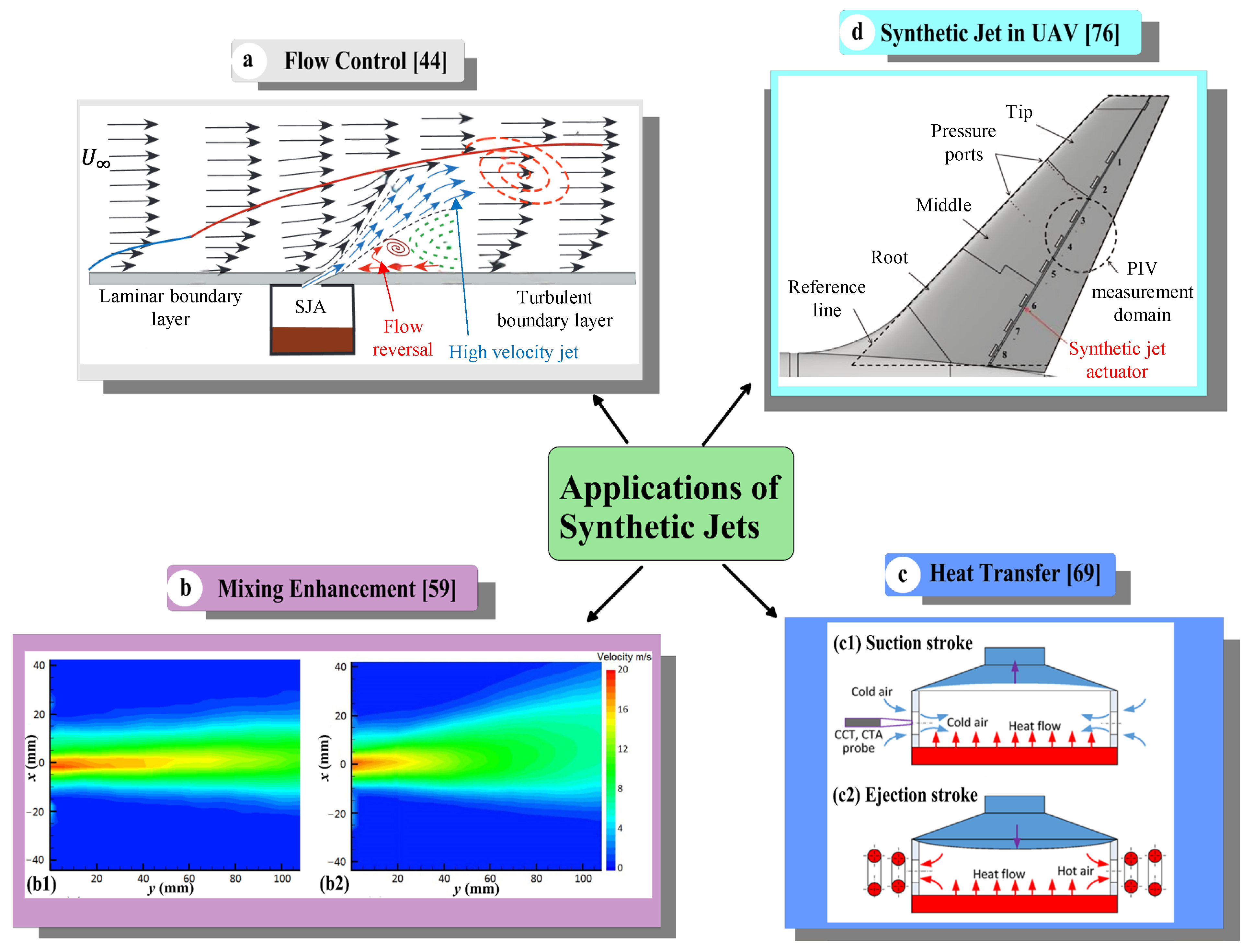

1.3. Applications of Synthetic Jets in Various Fields

Due to their unique design and operational advantages discussed earlier, synthetic jets have progressed beyond laboratory investigations and are increasingly utilized in various engineering applications. The major applications of synthetic jets are illustrated in

Figure 5. One of the most prominent areas is flow control (

Figure 5a), where synthetic jets inject momentum into the boundary layer, energizing near-wall fluid, generating coherent vortices, and suppressing flow separation. This leads to enhanced lift, reduced drag, and improved maneuverability in aerospace systems [

31,

38,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Synthetic jets are widely used to enhance mixing by introducing unsteady disturbances that intensify turbulence and promote entrainment. This is demonstrated in

Figure 5b, which shows the coaxial jet without synthetic jet actuation (

Figure 5b1) and with actuation (

Figure 5b2). The synthetic jets disrupt the potential core and broaden the shear layer, leading to a thickened outer shear layer and a reduced radial velocity gradient, clear indicators of enhanced entrainment (

Figure 5b2) compared to the case without synthetic jet actuation (

Figure 5b1) [

59]. The enhanced mixing leads to improved combustion efficiency and reduced emissions [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. They are also widely adopted in thermal management applications, where their unsteady nature disrupts thermal boundary layers and enhances convective heat transfer [

69]. During the cyclic operation of synthetic jets, the suction stroke draws in cool ambient air (

Figure 5c1), while the ejection stroke expels hot air (

Figure 5c2). This periodic jetting action improves entrainment, increases near-wall turbulence, and significantly enhances convective heat removal from the surface. This is particularly effective for cooling electronic components such as CPUs and GPUs [

15,

22,

43,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74]. Additionally, synthetic jets are employed in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) (

Figure 5d), where their compactness and controllability contribute to aerodynamic efficiency and flight control [

75,

76,

77,

78].

Together with these major areas, synthetic jets have also been explored for underwater propulsion and maneuvering in marine robotics, offering a compact and efficient solution for submerged environments [

75,

77,

78,

79,

80]. These diverse implementations highlight the versatility of synthetic jets and their potential to impact a wide spectrum of engineering domains.

Figure 5.

Applications of synthetic jets in (a) flow control, reproduced with permission from [

44]; (b) mixing enhancement, figure reproduced from [

59], licensed under CC BY 4.0; (c) heat transfer, reproduced with permission from [

69]; and (d) unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), reproduced with permission from [

76].

Figure 5.

Applications of synthetic jets in (a) flow control, reproduced with permission from [

44]; (b) mixing enhancement, figure reproduced from [

59], licensed under CC BY 4.0; (c) heat transfer, reproduced with permission from [

69]; and (d) unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), reproduced with permission from [

76].

1.4. Review Scope and Objectives

As discussed previously, SJs exhibit strong potential for flow control and thermal management applications, owing to their compact design, ZNMF, ease of integration into miniaturized systems, and independence from external fluid sources. However, a detailed review of the literature highlights three fundamental limitations affecting the practical deployment of synthetic jets, namely restricted jet formation, limited spanwise coverage, and rapid loss of momentum and coherence in the far field due to vortex diffusion. These core issues remain largely unaddressed in existing literature, where most studies focus on specific performance aspects without identifying or correlating the underlying challenges with specific design strategies. This review is the first to explicitly define these inherent drawbacks and systematically assess the technological advancements.

The review categorizes and evaluates four major SJ configurations, namely dual cavity jets, single actuator multi-orifice jets, coaxial jets, and synthetic jet arrays, based on their ability to mitigate these limitations. Each configuration is analyzed in terms of momentum delivery, spatial coverage, and vortex structure sustainability. Performance improvements through design modifications, actuator arrangements, and control of operating parameters are critically examined alongside unresolved challenges. By establishing a clear link between the observed limitations in single actuator configurations and the functional enhancements achieved through more advanced arrangements, this review offers a solid foundation for future research and design optimization. This assessment is crucial due to the rising demand for compact, efficient flow control along with thermal management solutions in miniaturized electronics, aerospace, and next-generation energy systems.

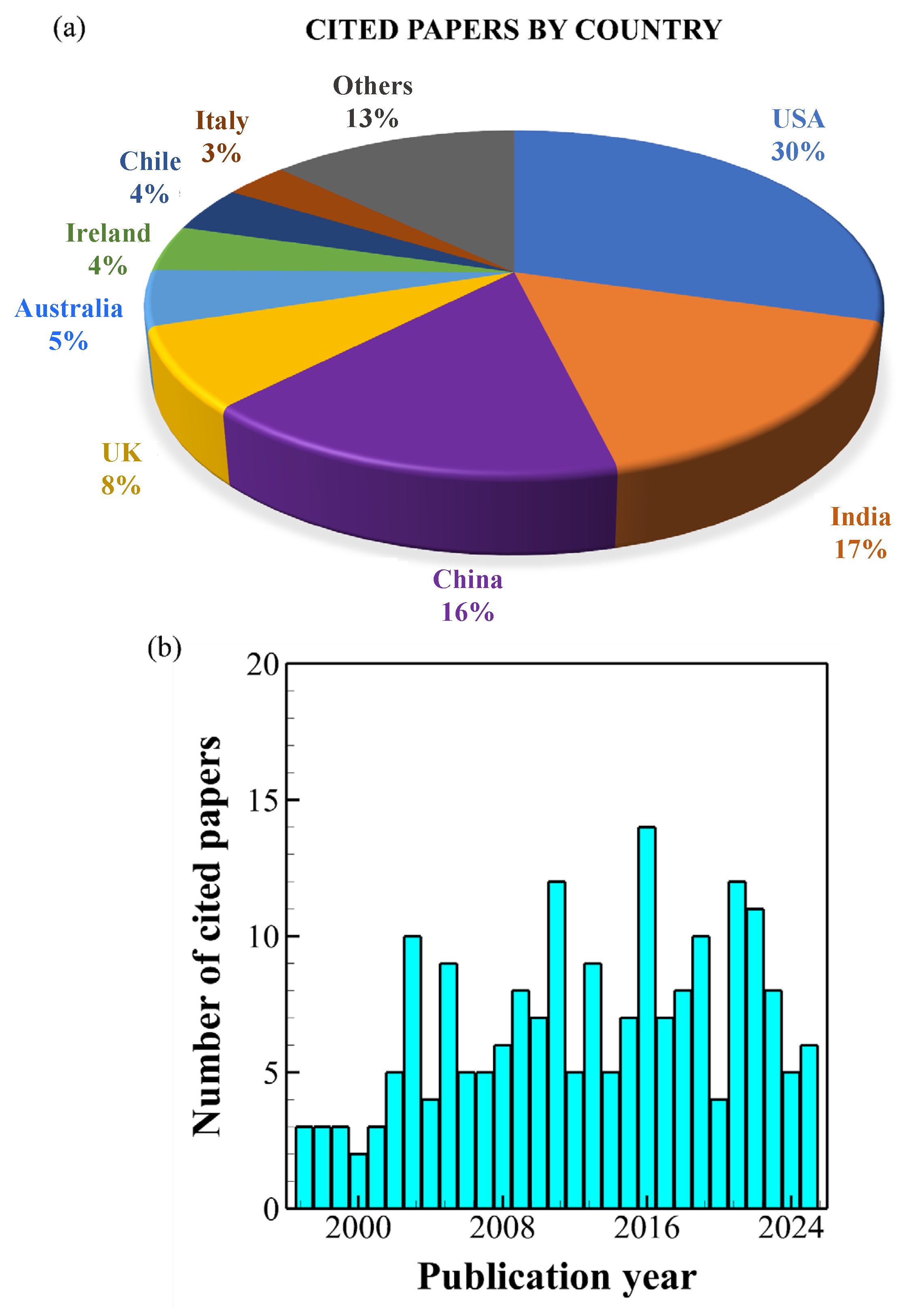

To provide a quantitative overview of the literature surveyed in this review,

Figure 6 presents the distribution of cited papers by country (a) and by year of publication (b). This illustrates the geographical spread and temporal evolution of research in synthetic jet technologies, highlighting growing international interest and increasing publication trends over the past two decades. In recent years, greater emphasis has been placed on the practical implementation of synthetic jets in cooling and flow control applications, reflecting a shift toward real-world applicability and system-level integration. This review offers a comprehensive synthesis of existing knowledge that not only clarifies key challenges and technological progress but also provides a valuable foundation for guiding future research and development efforts toward more effective and practical synthetic jet solutions.

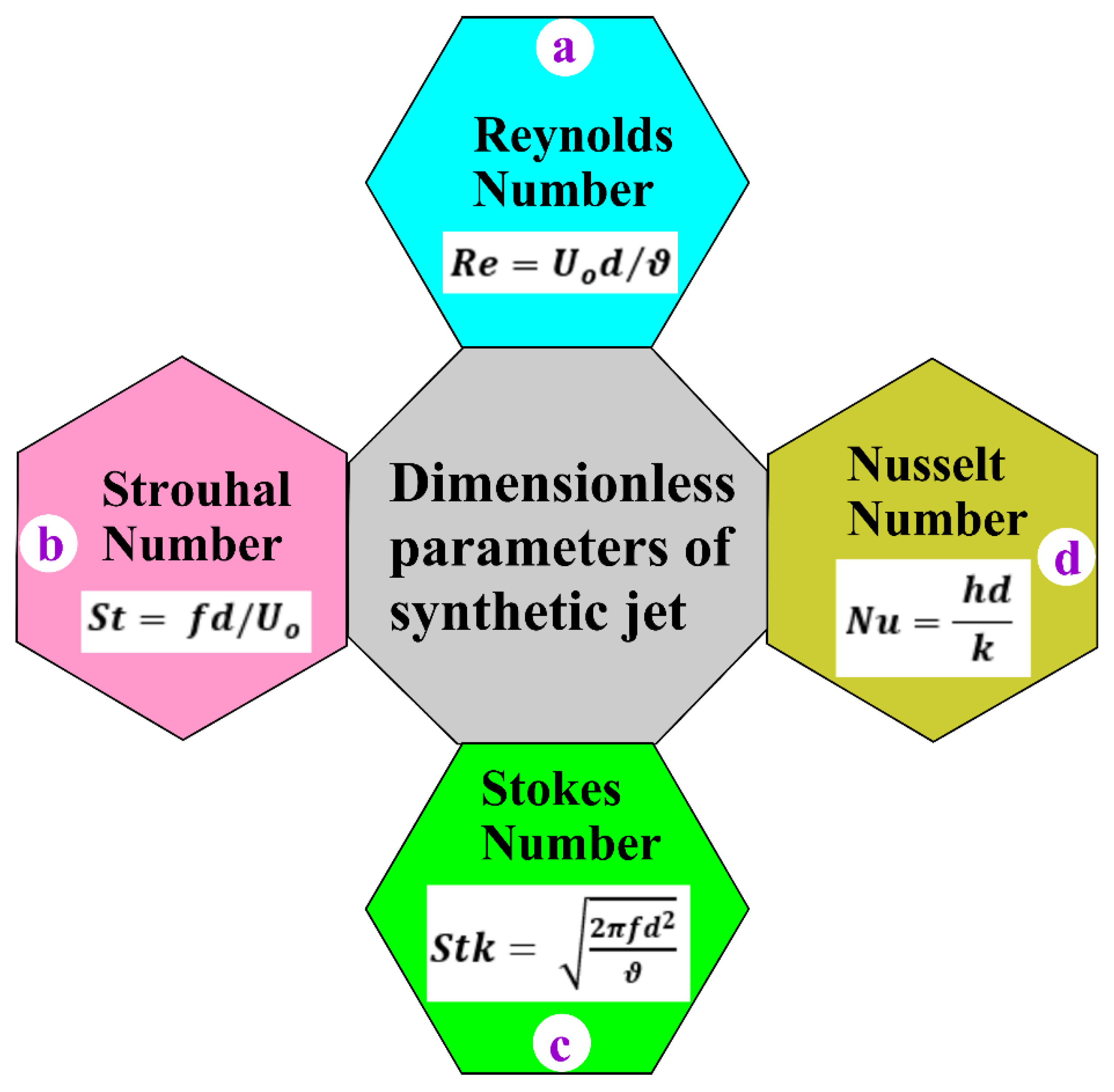

2. Key Parameters Governing Flow and Heat Transfer in Synthetic Jets

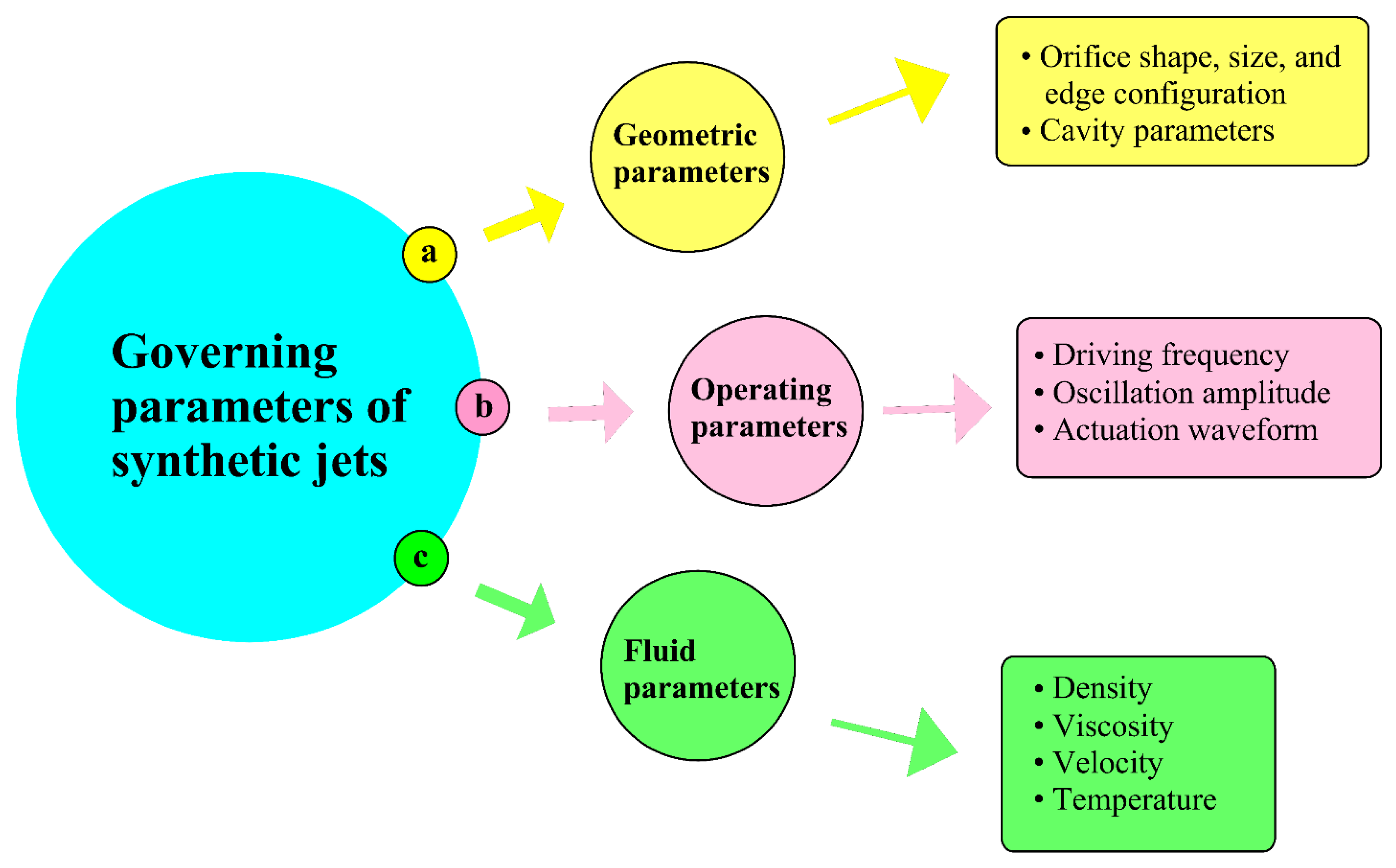

The performance of synthetic jets, encompassing both flow dynamics and heat transfer, is strongly governed by a combination of geometric, operational, and fluid parameters (

Figure 7). Additionally, various non-dimensional numbers (

Figure 8) are critical in describing the development and interaction of synthetic jets with the surrounding flow and thermal fields. This section outlines the key parameters that influence the overall behavior and effectiveness of synthetic jets.

2.1. Geometric Parameters of SJA

The geometry of an SJA plays a crucial role in defining its flow behavior and performance. Two primary geometric aspects govern this behavior, namely the orifice configuration, referring to its shape, size, and edge, and the cavity parameters (

Figure 7a). The orifice shape, size, and edge configuration directly influence the exit jet's velocity profile, directionality, and coherence [

81]. Circular, rectangular, and slit-shaped orifices generate distinct vortex structures and entrainment characteristics. Smaller orifices produce faster, more focused jets due to concentrated momentum, while larger ones yield slower, higher-volume jets with broader coverage [

82]. However, an increase in peak jet velocity resulting from a reduced orifice size does not necessarily lead to a proportional increase in Reynolds number or entrainment capability [

83]. The orifice edge configuration significantly affects vortex formation and jet performance; sharp edges enhance vortex roll-up and momentum flux, while rounded edges improve entrainment and mixing but reduce axial velocity and impingement strength [

84,

85].

The cavity parameters largely affect the actuator's resonant behavior and energy transfer efficiency. Together with the orifice, the cavity forms a system that closely resembles a Helmholtz resonator, where the air inside the cavity acts as a compressible spring, and the slug of air oscillating through the orifice behaves as an inertial mass [

86]. A larger cavity volume enhances compressibility, lowering the natural oscillation frequency, while a larger orifice area reduces inertial resistance, thereby raising the frequency [

87]. Optimal actuator performance typically occurs near the resonant frequency, where stronger vortex formation and higher jet velocities enhance flow control and heat transfer [

88].

2.2. Operating Parameters of SJA

A critical aspect of synthetic jet actuator operation is the membrane oscillation. The key input parameters controlling this oscillation include the driving frequency, oscillation amplitude, and actuation waveform (

Figure 7b), which govern jet formation and vortex dynamics, and influence both flow control and heat transfer performance.

2.2.1. Driving frequency ()

The actuation frequency of the oscillating membrane determines the rate at which SJs are produced during each oscillatory cycle. An increase in frequency typically leads to higher jet velocities and the formation of stronger vortex structures, which can be beneficial in applications requiring rapid and dynamic flow control. In contrast, lower frequencies tend to generate more stable jets with reduced turbulence, making them more suitable for conditions where steady flow behavior is desired [

87].

2.2.2. Oscillation amplitude ()

Amplitude reflects the extent of membrane displacement during each oscillation cycle. A larger amplitude typically induces greater fluid movement, resulting in stronger jet formation. This parameter significantly influences the evolution and spreading characteristics of the jet [

89]. Moreover, variations in amplitude influence the formation and spreading of vortices within the flow, which directly impacts the mixing efficiency and heat transfer performance of the jet.

2.2.3. Actuation Waveform

Synthetic jet actuators can be operated using various waveforms, including sinusoidal, square, and triangular signals. The choice of waveform influences the jet’s temporal behavior, leading to differences in velocity profiles and vortex dynamics. These waveforms affect the rate of diaphragm acceleration and deceleration during each cycle, which in turn alters the strength and structure of the expelled vortices. Square waveforms tend to produce sharper transitions and more abrupt vortex shedding, whereas sinusoidal signals generate smoother, more continuous flow development [

90,

91]. These variations affect the balance between suction and expulsion phases, altering the jet's symmetry, strength, and temporal characteristics, which collectively impact its overall performance. By modifying the waveform, the thermal and momentum transport characteristics of the jet can be adjusted to meet specific application requirements [

92].

2.3. Fluid Parameters in SJA

The thermophysical properties of the working fluid, including density, viscosity, velocity, and temperature, play a critical role in shaping the behavior of synthetic jets (

Figure 7c). These properties govern the momentum and heat transport mechanisms that influence the formation, evolution, and stability of vortical structures during each actuation cycle, particularly under varying thermal conditions [

31]. Density determines the inertial response and penetration capability of the flow [

13]. Viscosity affects the rate of vorticity diffusion, thereby influencing the coherence and dissipation of the jet [

93]. Fluid velocity contributes directly to the jet momentum and the vortex strength [

26,

94]. Temperature variations not only modify the intrinsic properties of fluid but also influence key dimensionless numbers, such as the Reynolds and Prandtl numbers, which are critical to both flow dynamics and thermal transport [

95]. These effects become increasingly significant in applications involving strong thermal gradients, where precise control of jet behavior is essential for optimal performance.

2.4. Characteristics of Dimensionless Numbers Governing Synthetic Jet Behavior

The dimensionless parameters simplify the influence of operating conditions and fluid properties into meaningful quantities that help understand patterns in vortex motion, jet development, and heat transfer. Various key dimensionless quantities, such as the Reynolds number (

), Strouhal number (

), Stokes number (

), and Nusselt number (

), as illustrated in

Figure 8, provide insight into the fundamental physics governing jet behavior and thermal transport.

Figure 8.

Nondimensional parameters governing the flow and heat transfer characteristics of synthetic jets.

Figure 8.

Nondimensional parameters governing the flow and heat transfer characteristics of synthetic jets.

2.4.1. Reynolds Number ()

The Reynolds number is a fundamental dimensionless parameter that characterizes the flow behavior of SJs (

Figure 8a). It indicates the nature of the flow regime, distinguishing whether the flow remains laminar or transitions to turbulence. In SJ applications, the Reynolds number affects vortex formation, jet penetration, and overall mixing behavior [

37].

The Reynolds number is defined as [

26]

where

is the time-averaged jet velocity during the ejection stroke,

is the orifice diameter or slot width, and

is the kinematic viscosity of the working fluid. The

is related to the stroke length and actuation frequency as

where

The denotes the stroke length, representing the effective displacement of the jet during the blowing half-cycle. The is the instantaneous centerline velocity at the orifice exit, and represents the period of one complete actuation cycle, where is the diaphragm frequency.

To account for the distributed nature of the exit velocity, Utturkar et al. [

96] later proposed a Reynolds number formulation based on the average velocity over time and space across the orifice area, i.e.,

where

is defined as

In this formulation,

represents the local velocity at the orifice exit as a function of time and transverse coordinate

, and

is the orifice area. The two velocity scales are related as

Both definitions are commonly used, depending on the experimental approach or modelling requirements. A higher Reynolds number typically correlates with increased jet momentum, enhanced vortex strength, and improved mixing and heat transfer performance [

97].

2.4.2. Strouhal Number ()

The Strouhal number (

Figure 8b) is a dimensionless quantity that governs the relationship between actuation frequency, orifice dimension, and time-averaged jet velocity. It can be expressed as [

26]

This parameter characterizes the interaction between periodic actuation and the inertia of the fluid, which plays a significant role in shaping the formation and spacing of vortical structures. It influences the generation of discrete vortex pairs during each actuation cycle by relating the actuation frequency and orifice geometry to the resulting fluid motion. According to Smith and Glezer [

26], the

is the inverse of the nondimensional stroke length and controls the axial distance from the orifice where vortex pairs or rings are shed. Experimental results indicate that at lower

values, vortex rings form farther apart, reducing mutual interaction and shifting the breakdown location downstream [

37]. On the other hand, high

values prevent proper vortex separation, resulting in flow being drawn back into the cavity during the suction phase, thereby disrupting jet formation. The vortex formation condition that incorporates the combined effects of Reynolds number,

, and Stokes number (

) was introduced by Holman et al. [

98]. For jets issuing from planar orifices, formation is observed when

and for axisymmetric jets, the corresponding criterion is

These expressions define the minimum conditions required for effective vortex roll-up and sustained jet formation during the ejection phase.

2.4.3. Stokes Number ()

The Stokes number (

Figure 8c) is another important parameter that influences the evolution of vortices in synthetic jet flows. It captures the combined effects of actuation frequency, orifice size, and fluid viscosity on the unsteady behavior of the flow near the orifice. For synthetic jets, the Stokes number is defined as [

99]

This quantity plays a crucial role in determining whether coherent vortices can form and separate from the orifice. Earlier investigations reported that the strength of the vortex roll-up mechanism diminishes as

decreases [

99]. Experimental results showed that when the

falls below 7, the shear layer cannot produce well-defined vortex structures [

99]. Generally, a Stokes number around or above 10 is considered necessary to ensure the formation of distinct vortex rings that can detach and propagate downstream, contributing to effective SJ formation.

2.4.4. Nusselt Number ()

The Nusselt number (

Figure 8d) is a key parameter for evaluating the convective heat transfer performance of SJs. It is defined as

where

is the convective heat transfer coefficient and

represents the thermal conductivity of the working fluid.

The area-average Nusselt number (

) can be expressed as:

Here, is the surface area of the heated object.

Synthetic jets enhance convective heat transfer by periodically ejecting and ingesting fluid, disrupting the thermal boundary layer and promoting vortex-induced mixing. The resulting Nusselt number is governed by vortex strength, actuation frequency, oscillation amplitude, and the orifice-to-surface spacing. Several studies [

11,

88,

100] have shown that careful adjustment of these operating conditions can significantly increase both local and average Nusselt numbers. This makes SJs particularly effective for thermal management applications.

3. Flow Characteristics of Synthetic Jets

A comprehensive overview of the geometric configurations, operating conditions, fluid properties, and non-dimensional parameters influencing synthetic jet behavior has been presented earlier. This section reviews key experimental and numerical studies that examine the effects of these factors on vortex dynamics and flow characteristics. In addition to offering deeper insight into the relevant flow phenomena, the discussion also highlights limitations and challenges related to synthetic jets, particularly in engineering applications with specific performance requirements.

3.1. Influence of Geometric Parameters on SJ Flow Characteristics

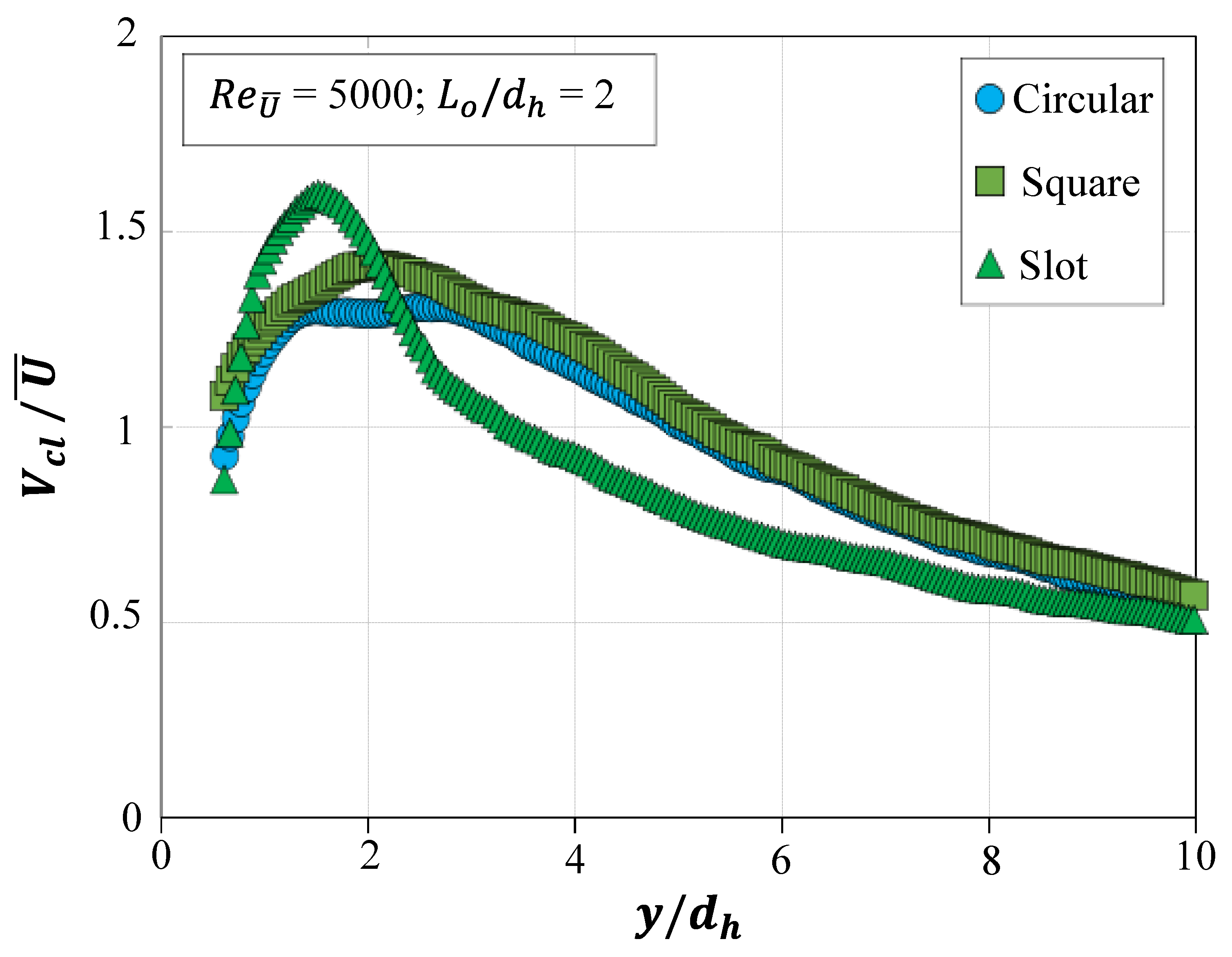

The geometric configuration of SJA exerts a critical influence on jet formation, flow development, and downstream momentum transfer. For the same orifice area, actuation frequency, and actuation amplitude, a comparison of circular, square, slot, and triangular orifices revealed that the triangular orifice performs best in terms of peak centerline velocity (

) [

82]. The percentage enhancement of peak

for the triangular orifice is approximately 6%, 24%, and 31% compared to the circular, slot, and square orifices, respectively. However, the triangular orifice exhibits the highest decay in

among all the orifice shapes. For instance, the triangular orifice shows a decay of approximately 42% in

between

1 (where

reaches its peak) and

4 [

82]. Here,

is the hydraulic diameter, defined as

= 4 × orifice area / perimeter. This significant reduction in

is attributed to the pronounced weakening of jet strength in the downstream direction [

82]. A similar drastic reduction in

for circular, square, and slot orifices can also be observed in

Figure 9, indicating that all orifice shapes experience substantial weakening of jet strength with downstream distance [

101]. Moreover, studies have shown that rectangular orifices generate broader vortex structures and enhanced lateral spreading; however, rapid diffusion of vortex strength in the far field remains a significant drawback [

82,

102].

The design of the orifice edge adds an additional dimension to the aerodynamic behavior. Sharp orifice edges typically facilitate stronger vortex roll-up and higher momentum flux [

84], whereas rounded or beveled edges tend to suppress flow separation and enhance lateral entrainment [

85]. Although the latter improves mixing, it often reduces axial velocity and impingement strength. Further insights from Smith and Swift [

103], Shuster and Smith [

37], and Cater and Soria [

18] revealed that orifice edge design affects vortex roll-up and propagation during the expulsion phase. Nani and Smith [

104] quantified the impact of inner edge rounding, showing that it reduces acoustic power input up to a radius of 0.5

. Beyond this threshold, power consumption increases due to loss of wall attachment and suction inefficiency.

Figure 9.

Variation of jet centerline velocity (

) along the streamwise direction (

) for different orifice shapes. Figure reproduced from [

101], licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.

Variation of jet centerline velocity (

) along the streamwise direction (

) for different orifice shapes. Figure reproduced from [

101], licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Internal cavity dimensions further modulate jet characteristics, especially through their interaction with the acoustic response of the actuator. A reduced cavity height strengthens vortex shedding and improves near-field momentum transfer [

85,

105,

106,

107]. Conversely, under resonance conditions, larger cavities can support enhanced jet velocities by amplifying acoustic oscillations [

108]. This resonance-based performance improvement has been extensively documented [

87,

109,

110], and is often associated with peak output occurring at or near the actuator’s Helmholtz frequency [

86,

111]. These studies collectively highlight the importance of tuning cavity dimensions to balance jet strength, frequency response, and energy efficiency.

Along with poor far field performance, another primary limitation of single actuator configurations is that the generated stroke volume is inherently constrained by physical displacement and chamber size of the actuator. As a result, the time-averaged mass flow rate remains relatively low when considered for various engineering applications [

21,

112,

113,

114].

3.2. Effect of Non-Dimensional Parameters on SJ Flow Dynamics

As discussed earlier, the flow characteristics of synthetic jets are governed by several dimensionless parameters, including the Reynolds number, , and , along with that is inherently related to both Reynolds number (Equations 1 and 2) and (Equation 7) through its dependence on . These dimensionless parameters encapsulate the effects of actuation frequency, oscillation amplitude, and fluid properties, thereby governing jet flow behaviors.

Operation of the SJA at low

limits SJ formation by preventing vortices from moving far enough from the orifice during the blowing phase. This causes stronger suction effects that disrupt coherent vortex development, resulting in weaker jets and reduced fluid mixing, which are major drawbacks restricting effective jet formation [

21]. As

increases, the spacing between successive vortices grows, significantly affecting the jet's spatial development. In rectangular configurations, a higher

enhances lateral spreading but causes a transition from a discrete vortex train to a more continuous jet flow, resulting in a weakened jet due to increased vortex diffusion [

27]. The best performance occurs in the range 4 ≤

< 8, where a balance is achieved between vortex strength and stability. In contrast, for

8, the primary vortices become unstable and eventually lose coherence, giving rise to trailing jets that dominate the downstream flow [

115].

A higher

produces stronger and more stable vortex rings, thereby enhancing momentum flux [

116]. However, as the jet propagates away from the orifice, vortex diffusion causes a rapid decay in jet velocity. For example, Shuster and Smith [

37] showed that synthetic jets operating at

= 10

4 experience a 33% drop in peak streamwise velocity between

= 2 and 5, and nearly a 50% reduction between

= 5 and 10, highlighting the significant impact of vortex diffusion in the far field. In flow control applications, moderate Reynolds numbers combined with a low-frequency actuation have shown improved flow reattachment using less momentum input than high-frequency strategies [

117]. Nonetheless, maintaining jet effectiveness at higher Reynolds numbers remains challenging due to enhanced turbulence and diffusion losses in the far field.

The

St integrating actuation frequency, flow velocity, and jet size (Equation 7) characterizes jet formation and behavior. In two-dimensional and axisymmetric jets, the

ratio governs the onset of vortex shedding and the development of coherent flow structures [

96,

98]. Operating outside the optimal

range can inhibit the formation of discrete vortex rings or lead to unstable and ineffective flow regimes. For instance, in high Reynolds number impinging jets, lower Strouhal numbers shift the flow dominance from the primary jet to trailing jets, thereby weakening the actuator control capability and effectiveness [

118]. Additionally, spanwise instabilities and secondary flow structures, such as rib-like vortices, emerge under certain operating conditions, further contributing to the decay of jet strength. The

plays a pivotal role in dictating the onset, scale, and evolution of these flow features, as it influences both the initial vortex formation and the subsequent development of three-dimensional instabilities [

119].

The Stokes number has emerged as a particularly important nondimensional parameter for evaluating synthetic jet coherence. Coherent jets typically form only when the Stokes number exceeds a critical threshold, often around 8.5, and when the stroke length ratio is greater than 4 [

99]. Below these values, vortex formation is weak or suppressed entirely, leading to low-momentum jets incapable of effective flow control or heat transfer. As the jet moves downstream, the increasing Kolmogorov length scale reflects vortex breakdown and reduced mixing efficiency [

49]. Research has shown that counter-rotating vortex pairs near the orifice dissipate rapidly, becoming indistinct beyond one wavelength and causing significant velocity decay beyond

10, thereby highlighting challenges to long-range jet effectiveness [

120]. This rapid jet diffusion in the far field has also been demonstrated earlier (

Figure 4a) by Cater and Soria [

18].

While appropriate values of , , , and enhance near-field entrainment and vortex coherence, these advantages progressively weaken downstream due to vortex breakdown and diffusion. The combined limitations of insufficient jet formation and reduced jet strength beyond the near field represent fundamental challenges to employing SJs in applications demanding sustained and spatially extensive flow control.

3.3. Impact of Waveform on Flow Dynamics of SJs

The shape of the actuation waveform directly impacts the dynamic response of SJs, influencing the suction and ejection of fluid through oscillatory membrane motion. This, in turn, affects vortex formation and the momentum of the jet. In the region close to the wall, sine wave excitation typically leads to optimal performance, as it facilitates smoother transitions between the suction and blowing cycles, supporting stable vortex formation [

68]. However, as the jet moves farther from the orifice, square waves prove more effective in delivering momentum due to their higher power input, enhancing jet strength. On the other hand, triangular waveforms fail to effectively stabilize the flow, resulting in weaker jet performance and a higher tendency for wake unsteadiness [

68].

The type of actuator used further affects the jet velocity. With piezoelectric actuators, square and pulse waveforms generate stronger jets compared to sine wave excitations, which produce lower peak velocities [

14]. The way the waveform is modulated also plays a significant role. Dual sine waves, when modulated at low frequencies and voltages, result in higher velocity ratios than single sine inputs at higher voltages, providing a more energy-efficient approach to generating momentum [

121]. Similarly, square and sawtooth waveforms enhance the velocity profiles, with square waveforms producing the most robust jets in terms of peak output [

122,

123].

4. Heat Transfer Characteristics of Synthetic Jets

Here, we focus on the heat transfer behavior of SJs under various geometric and nondimensional configurations, providing a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which SJs enhance heat transfer. Additionally, the effectiveness of SJs in various cooling applications is examined, along with the challenges and limitations associated with their use for thermal enhancement.

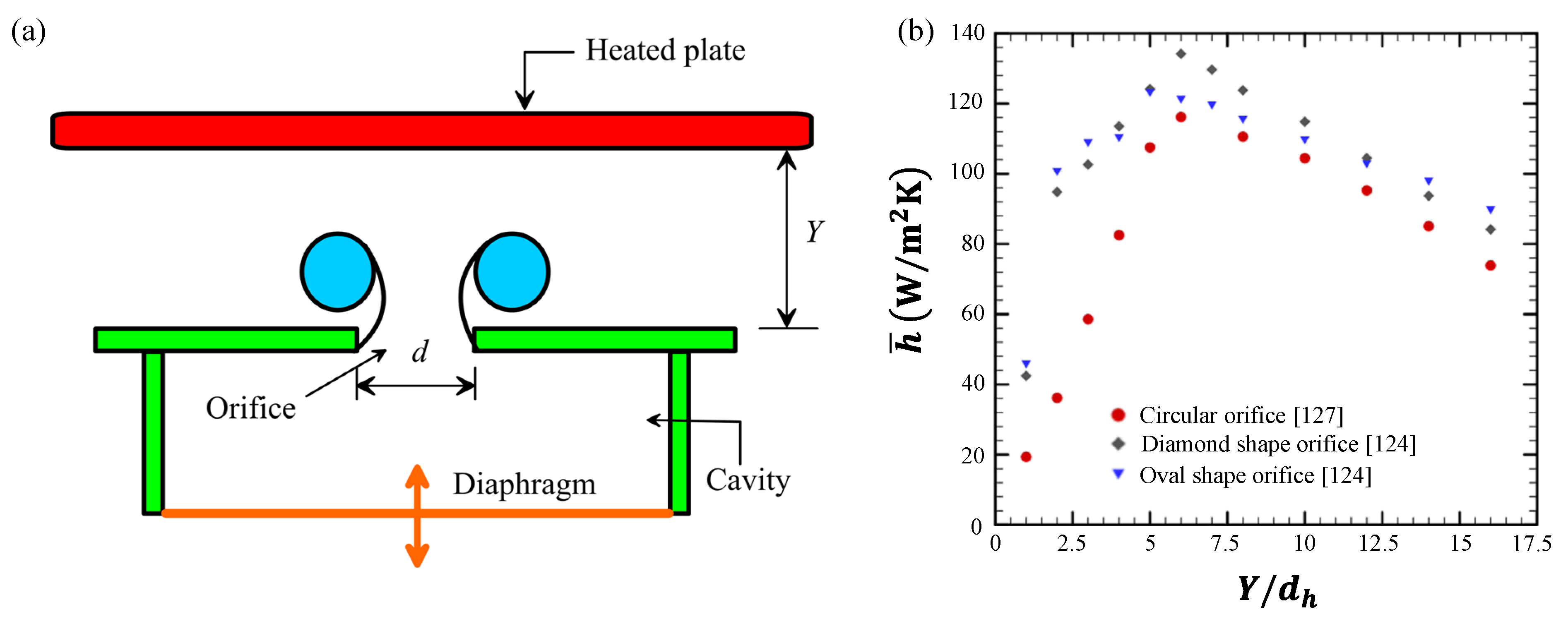

4.1. Influence of Geometric Parameters on Synthetic Jet Heat Transfer Characteristics

A synthetic jet impingement configuration illustrating the jet-to-surface spacing (

) is shown in

Figure 10(a). Among the common orifice shapes, such as circular, square, and rectangular, square orifices exhibit strong heat transfer performance in the near field but experience a significant decline as

increases, showing approximately a 46% drop in

between

6 (where heat transfer peaks) and

20 [

81]. This significant drop in heat transfer is attributed to the drastic loss of jet strength at larger spacings [

81]. A similar trend is observed for circular and rectangular orifices, where thermal enhancement diminishes noticeably with increasing

[

81]. Nonconventional orifice shapes, such as diamond and oval, have demonstrated superior thermal performance compared to the traditional circular configuration (

Figure 10b). At 200 Hz, diamond orifices provide up to 17% higher area-average heat transfer coefficient (

) than circular ones (

Figure 10b). However, a significant decline of approximately 40% in thermal performance is observed as the jet-to-surface distance increases from

6 to

16 [

124]. Oval orifices perform better at smaller

and are particularly effective in compact configurations (

Figure 10b), but like others, their efficiency deteriorates with

[

124]. When orifice shapes with equal exit areas are compared, rectangular geometries offer slightly better stagnation point performance, while circular ones yield more uniform heat distribution, especially at larger spacings. Despite variations in geometry, the overall trend remains a consistent decline in thermal performance with increasing

[

41].

The roles of orifice diameter, aspect ratio, and cavity depth are equally significant. Among these, the aspect ratio significantly influences near-wall behavior and jet development. Elliptical orifices with moderately low aspect ratios around 1.4 have been shown to enhance heat transfer at smaller

(<6) [

125]. Increasing the aspect ratio tends to produce elongated vortex structures that improve mixing and momentum exchange near the surface compared to circular jets, thereby further enhancing heat transfer. However, increasing the aspect ratio beyond a certain threshold does not necessarily yield further improvement. In fact, doubling the aspect ratio has been associated with a decline in heat transfer performance by approximately 15%, highlighting that the geometric advantage is limited to specific operating conditions [

125]. Similarly, increased cavity depth and hydraulic diameter contribute positively to heat transfer, with maximum Nusselt numbers typically occurring around

= 6 [

126]. Additionally, optimizing the cavity design to operate at the actuator’s resonance frequency can significantly enhance heat transfer; however, this improvement diminishes as the jet-to-surface spacing increases beyond an optimal range [

127]. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that, although geometric optimization can significantly enhance thermal performance in the near field, the rapid decay of jet strength and coherence at greater distances remains a fundamental limitation [

128,

129,

130,

131].

Extensive investigations into orifice shape, size, and cavity configuration have demonstrated that thermal performance can be optimized under specific conditions. However, a consistent pattern emerges across the literature as synthetic jets are fundamentally limited by a rapid decline in momentum and vortex structure beyond the near field. This leads to a marked drop in heat transfer performance, typically in the range of 40% – 46% as spacing increases. The degradation is due to vortex diffusion, which disrupts the coherence of the jet and limits its effectiveness in the far field.

4.2. Influence of Dimensionless Parameters on Heat Transfer

The thermal performance of SJs is closely tied to their unsteady vortex dynamics and governed by , , , and . These parameters collectively influence the formation, strength, and coherence of vortex structures, thereby modulating both local and global heat transfer behavior.

4.2.1. Nondimensional Stroke Length

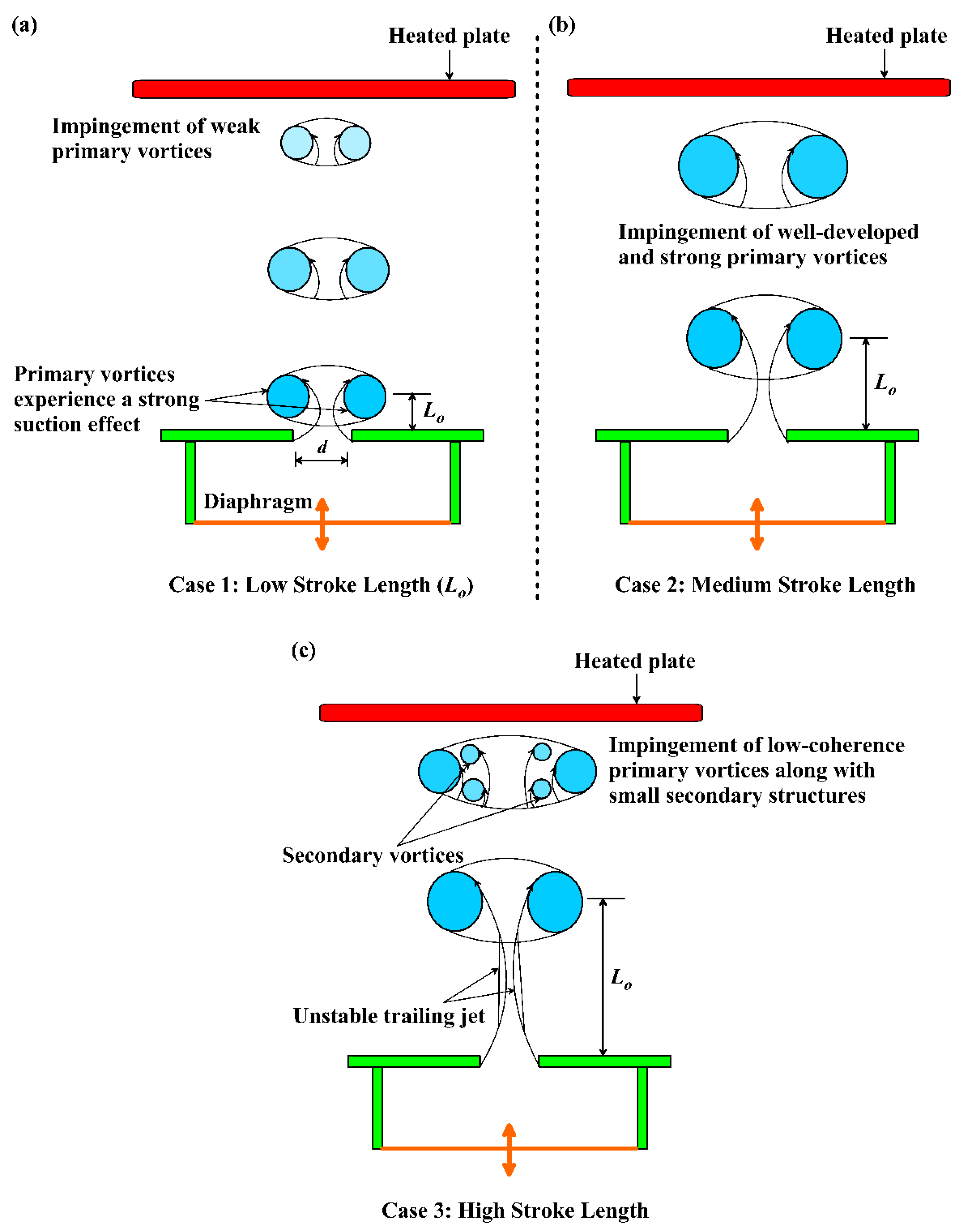

The

serves as a governing parameter for the thermal performance of SJs by regulating the formation, strength, and propagation of vortex rings. The dynamics of the vortices and the impingement heat transfer behavior of the synthetic jet operated at low, moderate and high

are illustrated in

Figure 11. At low values of

4 (

Figure 11a), the strong suction effect during the suction stroke disrupts vortex formation, resulting in underdeveloped primary vortices that dissipate rapidly. This leads to weak impingement and limited heat transfer enhancement (

Figure 11a) [

115]. As

increases to a moderate range between 6 and 8, coherent vortex structures develop, enabling more effective momentum transfer and improved convective transport (

Figure 11b). Within this regime, a marked increase in heat transfer at the stagnation region is observed, consistent with phase-resolved measurements that identify a transition in vortex behavior around

5 [

100]. However, at higher

values (

Figure 11c), the unstable trailing jet promotes vortex instabilities and the formation of small secondary vortical structures, which reduce the coherence of the primary vortices before they impinge on the heated surface, leading to diminished thermal performance [

115].

Experimental findings further support this trend, showing an enhancement of approximately 105% in the peak

at

2 when the stroke length ratio is reduced from

= 13.75 to 7.86 [

127]. However, even at the optimal

7.86, a substantial 64% drop in

is observed between the near field (

2 corresponding to the peak) and the far field (

14), which is attributed to the pronounced reduction in jet strength with increasing

. This decline in far-field performance, despite operating at the optimal

, aligns with findings reported by other researchers [

127,

132]. Ineffective heat transfer in the far field was also observed by Chaudhari et al. [

127] for synthetic jets operating within a Reynolds number (

) range of 1500 to 4200. A similar trend was reported by Persoons et al. [

133] across varying Strouhal numbers (

= 0.15 − 0.35), indicating that the diminished thermal performance in the far field is largely insensitive to changes in these parameters.

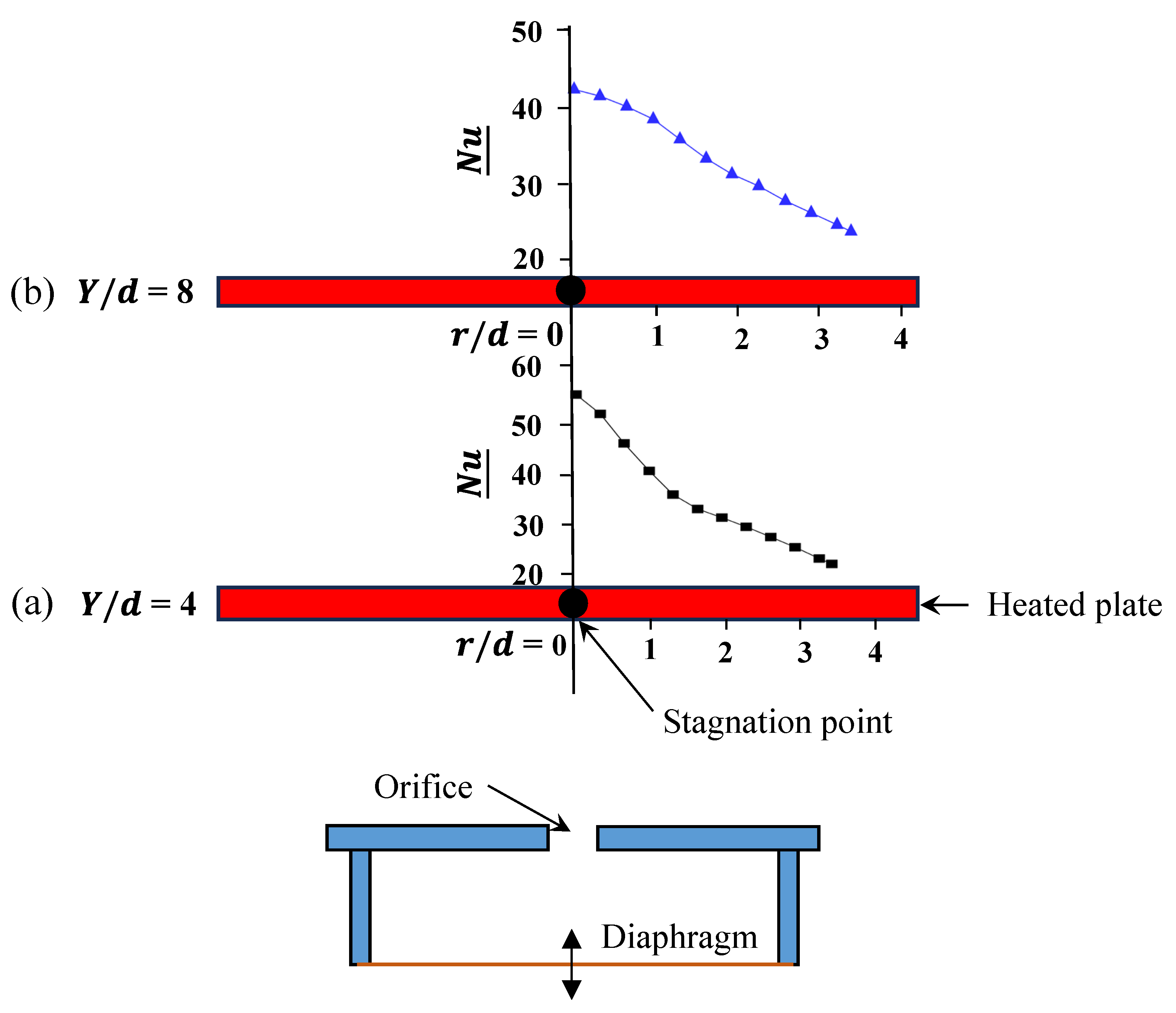

Even when operated at a moderate

(= 10), synthetic jets exhibit another primary drawback, namely limited spanwise coverage (

Figure 12). The radial distribution (

) of the time averaged Nusselt number (

) at

5250 demonstrates a consistent decline in heat transfer intensity away from the jet centreline [

134]. Regardless of

(

Figure 12), the heat transfer performance reduces noticeably with increasing radial distance. For instance, at

4,

decreases by approximately 52% between

0 and 3.5 (

Figure 12a), indicating a significant loss in thermal effectiveness across the surface. This observation reflects the concentrated nature of vortex-induced momentum transfer in synthetic jets, which remains dominant near the core but weakens rapidly with lateral distance. As a result, the inability to maintain strong radial coverage limits the suitability of synthetic jets for applications requiring broad and uniform thermal control [

134]. This limitation is further highlighted in the work of Rylatt and O’Donovan [

135], where thermal enhancement was predominantly confined to the core region.

Although operating at optimal stroke lengths enhances near-field heat transfer due to coherent vortex formation, SJs exhibit poor thermal performance in the far field as jet strength rapidly deteriorates with distance. Moreover, the spanwise coverage remains limited, as the influence of coherent structures is largely confined near the jet axis, restricting the effective cooling of large surface areas.

Figure 12.

Radial distribution of time-averaged Nusselt number (

) for the synthetic jet operated at

5250,

= 10 at (a)

= 4 and (b)

= 8, derived from data in [

134].

Figure 12.

Radial distribution of time-averaged Nusselt number (

) for the synthetic jet operated at

5250,

= 10 at (a)

= 4 and (b)

= 8, derived from data in [

134].

4.2.2. Influence of Oscillation Frequency

Frequency, though dimensional, is often characterized by dimensionless parameters like the Stokes number (Equation 10), which relates frequency, orifice diameter, and fluid viscosity. SJAs perform optimally when operating near resonant frequencies, including mechanical or diaphragm resonance frequency (

) and fluidic or Helmholtz resonance frequency (

). The diaphragm resonance is primarily determined by the physical properties of the actuator membrane and its geometry [

134], while Helmholtz resonance is influenced by cavity and orifice dimensions [

136]. At these resonant conditions, membrane displacement and pressure oscillations are maximized, thereby enhancing the volume and strength of fluid ejection [

86,

87,

88]. Previous studies have reported that for both circular and square orifices, the heat transfer increases with excitation frequency and reaches a maximum at the Helmholtz resonant frequency, after which it begins to decline [

81,

127]. However, even at the optimal resonant frequency, the area-averaged heat transfer coefficient in the far field (

= 20) shows a substantial decrease, with a reduction of about 40% for the circular orifice and about 45% for the square orifice compared with their respective peak values (

6.25 for both orifices) [

81,

127]. Similarly, SJAs operated under different Reynolds numbers and heat flux conditions reveal that although resonance improves local mixing and impingement, the strength of the vortices deteriorates rapidly with increasing axial distance [

11].

The frequency of oscillation significantly influences the near-field, far-field, and overall performance of SJAs [

137,

138]. Even beyond the resonance frequency (>

), SJAs demonstrate enhanced heat transfer in the near field (

≈ 5) at a higher excitation frequency. This improvement is attributed to the more rapid generation and accumulation of coherent vortices near the orifice, which impinge collectively and enhance local mixing [

137]. Ghaffari et al. [

138] made a similar observation and further reported that the high frequency leads to increased power consumption and noise. This, in turn, reduces the coefficient of performance (COP), particularly in configurations operating above the diaphragm or Helmholtz resonance. Despite marginal gains in convective enhancement, the associated energy inefficiency and acoustic penalties make such operating conditions less favorable for practical applications [

138]. Moreover, these densely packed vortices lose coherence rapidly as they propagate downstream, breaking into smaller, less effective structures, and consequently diminishing far-field performance [

137,

139]. In contrast, at lower frequencies, the spacing between successive vortex rings is larger, allowing each vortex to impinge independently on the target surface. This improves coherence retention and leads to better heat transfer further downstream [

137].

To extend synthetic jet functionality beyond conventional frequency limits, operating in the ultrasonic regime (above 20 kHz) has shown promise in enhancing heat transfer by generating densely packed vortices that behave like a quasi-steady jet [

19]. Piezoelectric-driven ultrasonic SJAs offer compactness and low noise, making them well-suited for micro-scale thermal applications [

140,

141]. Even with these advantages, far-field ineffectiveness in heat transfer is still observed due to the rapid decay of jet momentum downstream [

19]. Together with this, excessively short stroke lengths at ultrasonic frequencies can limit net fluid displacement and volumetric flow rate [

142], while thermal loading and material fatigue pose additional reliability concerns. Although operating SJAs at optimal (resonant) or ultrasonic frequencies enhances near-field performance, the steep decline in far-field effectiveness remains a concern for synthetic jets.

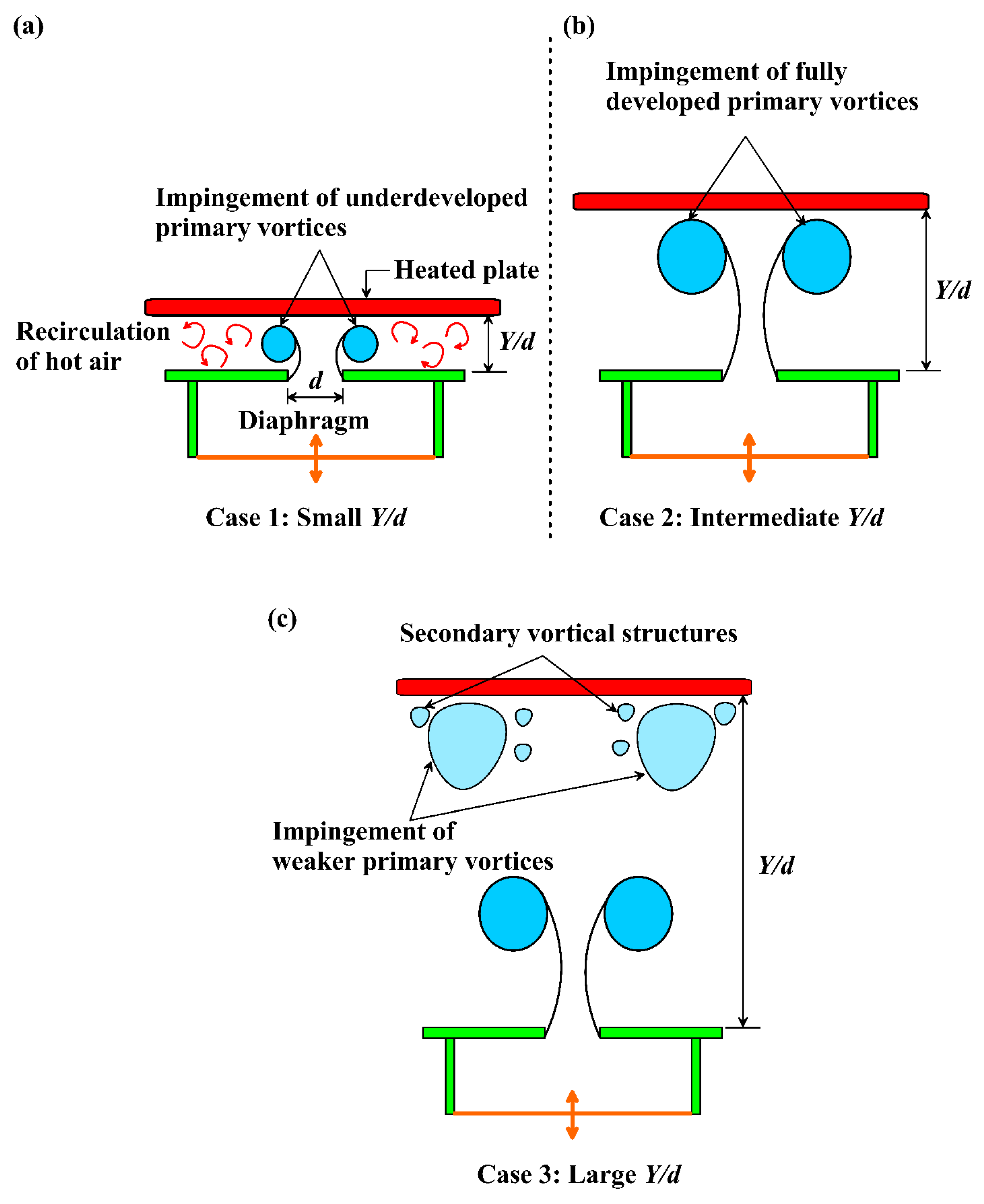

4.2.3. Jet-to-Heated Plate Distance ()

The behavior of synthetic jets at different

values has been extensively studied, revealing distinct regions of performance [

11,

23,

40,

42,

100,

128,

133,

137,

143,

144,

145,

146]. Based on previous findings [

127], the relationship between heat transfer and

can be classified into three stages: increasing heat transfer (

< 5), maximum heat transfer (

= 5 – 9), and decreasing heat transfer (

> 9). These three trends are linked to three stages of jet development: prematured (small

), matured (intermediate

), and over-matured (large

) as explained in

Figure 13.

When

is small, the limited spacing between the orifice and the target surface prevents the vortices from fully developing before reaching the surface. In addition, the confined spacing traps hot air and promotes recirculation (

Figure 13a). The heat transfer thus increases with increasing

in this regime [

71,

132]. The intermediate values of

(

Figure 13b) allow for the full development of the primary vortices, with the impingement of coherent vortical structures on the surface resulting in the highest heat transfer [

11]. On the other hand, when

is large (

Figure 13c), the primary vortices lose significant coherence and even break into small vortical structures before impingement, leading to a sharp decline in cooling performance. Such behavior is consistently reported across multiple studies [

81,

127,

137,

138,

146,

147,

148,

149]. Gillespie et al. [

11] noted up to a 36% drop in heat transfer between

= 18 (intermediate) and

= 23 (large).

In addition to heat transfer decay with increasing

, synthetic jets suffer from significant limitations in spanwise coverage. For the single-orifice SJA at

= 6, a pronounced reduction in heat transfer is observed across the span, with the Nusselt number dropping by approximately 58% from the stagnation point (

= 0) to the outer region (

= 4) [

150]. This is attributed to the rapid spanwise decay in jet strength [

150].

5. Technological Advancements of Synthetic Jets

A detailed flow and heat transfer study identified three fundamental drawbacks of SJs: (a) limited jet formation, particularly when driven by a single actuator; (b) reduced spanwise effectiveness, which limits their applicability in scenarios requiring wide area coverage; and (c) diminished far field performance due to the rapid decay of jet strength caused by strong vortex diffusion. Collectively, these limitations constrain the practical implementation of synthetic jets in real-world applications. Here, various technological advancements aimed at addressing these limitations are discussed in detail, with a focus on their effectiveness in enhancing SJ performance.

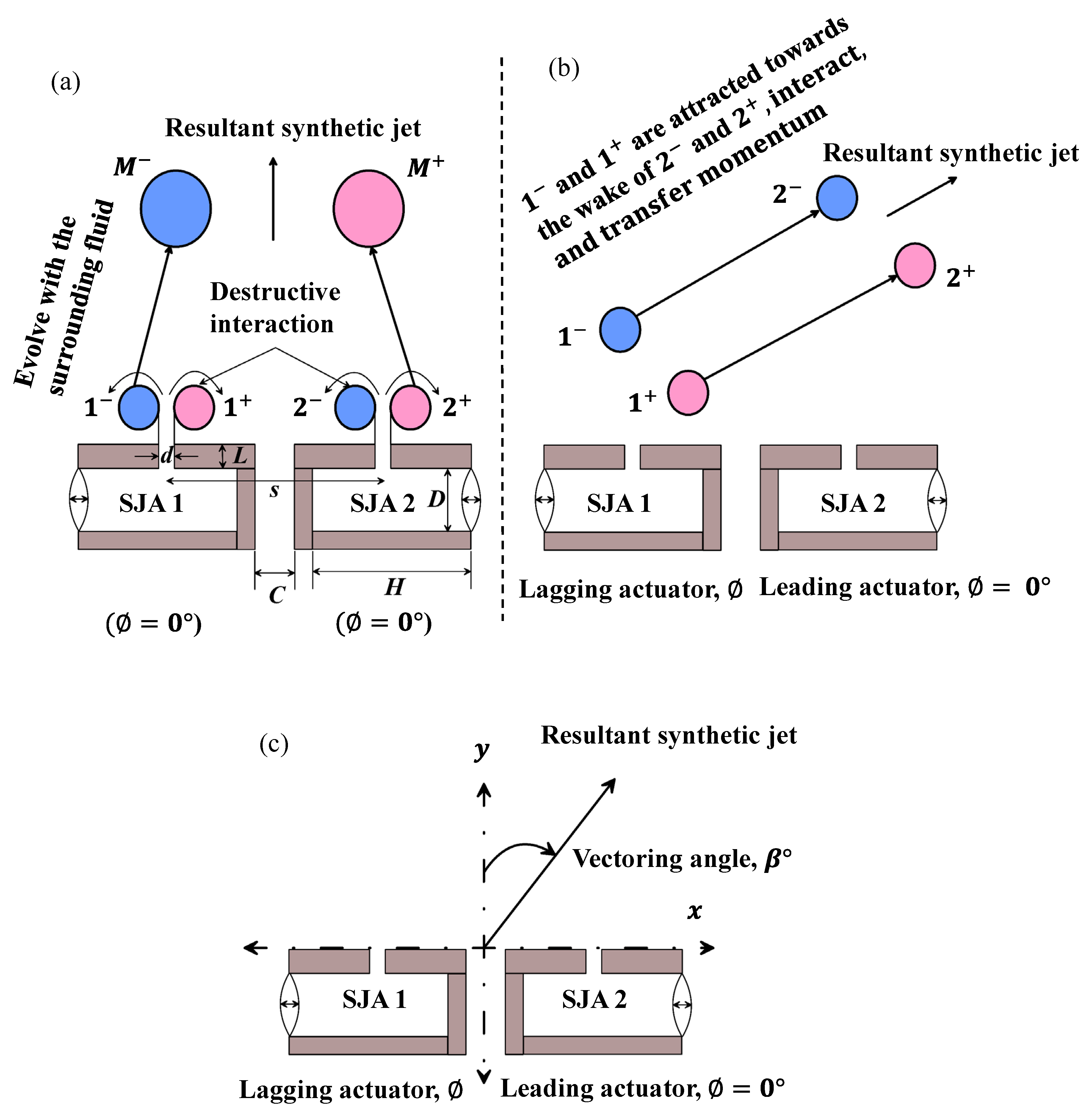

5.1. Dual Cavity Synthetic Jets (DSJs)

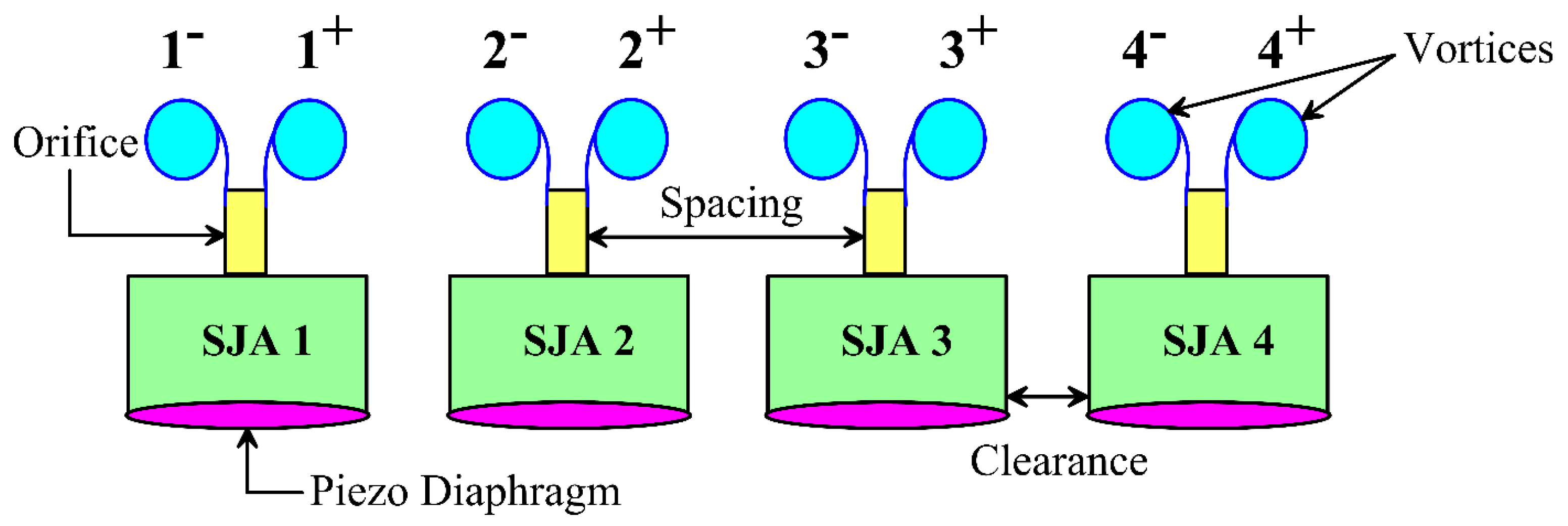

Dual synthetic jets (

Figure 14), consisting of two actuators adjacent to each other and operating either in phase or out of phase, offer greater control over vortex interactions compared to a single SJ [

112]. When the DSJ operates in phase (

0°), each actuator generates a pair of counter rotating vortices, namely vortices

and

from SJA 1, and

and

from SJA 2 (

Figure 14a). Due to their opposite sense of rotation, the inner vortices (

and

) undergo destructive interaction near the centerline, while the outermost vortices (

and

) evolve through interaction with the ambient fluid to form merged vortices, denoted as

and

, respectively (

Figure 14a). These merged vortices convect in a straight downstream direction (

Figure 14a and a). Studies have reported that under in-phase operation, the volume flow rate produced by the DSJ is approximately twice that of a single synthetic jet actuator (

Figure 15c) [

112].

In contrast, when a phase difference (

) is introduced between the actuators (

Figure 14b), with SJA 2 leading SJA 1, vortices

and

form earlier and convect with their self-induced velocities. The wake generated by the leading vortices entrains the lagging vortices

and

, which share the same rotational direction. This interaction leads to momentum transfer from the lagging to the leading vortices, which in turn causes vectoring of the resultant jet toward the leading actuator (

Figure 14b and b). This directional control, or vectoring, was later attributed to a mechanism known as the "attract impact causing deflection" (AICD) [

151]. The vectoring angle (

) is typically measured as the angle between the vertical axis (

= 0) and the direction of convection of the resultant jet (

Figure 14c and

Figure 15b). The angle is considered positive when the jet vectors toward the leading actuator and negative when it vectors toward the lagging actuator [

114]. Further studies have shown that the vectoring angle increases with increasing phase difference [

112,

152].

Figure 14.

Schematic representation showing (a) dual synthetic jets operated in phase (), (b) DSJ operated with a phase difference where SJA 2 leads SJA 1, and (c) demonstration of vectoring angle () calculation.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation showing (a) dual synthetic jets operated in phase (), (b) DSJ operated with a phase difference where SJA 2 leads SJA 1, and (c) demonstration of vectoring angle () calculation.

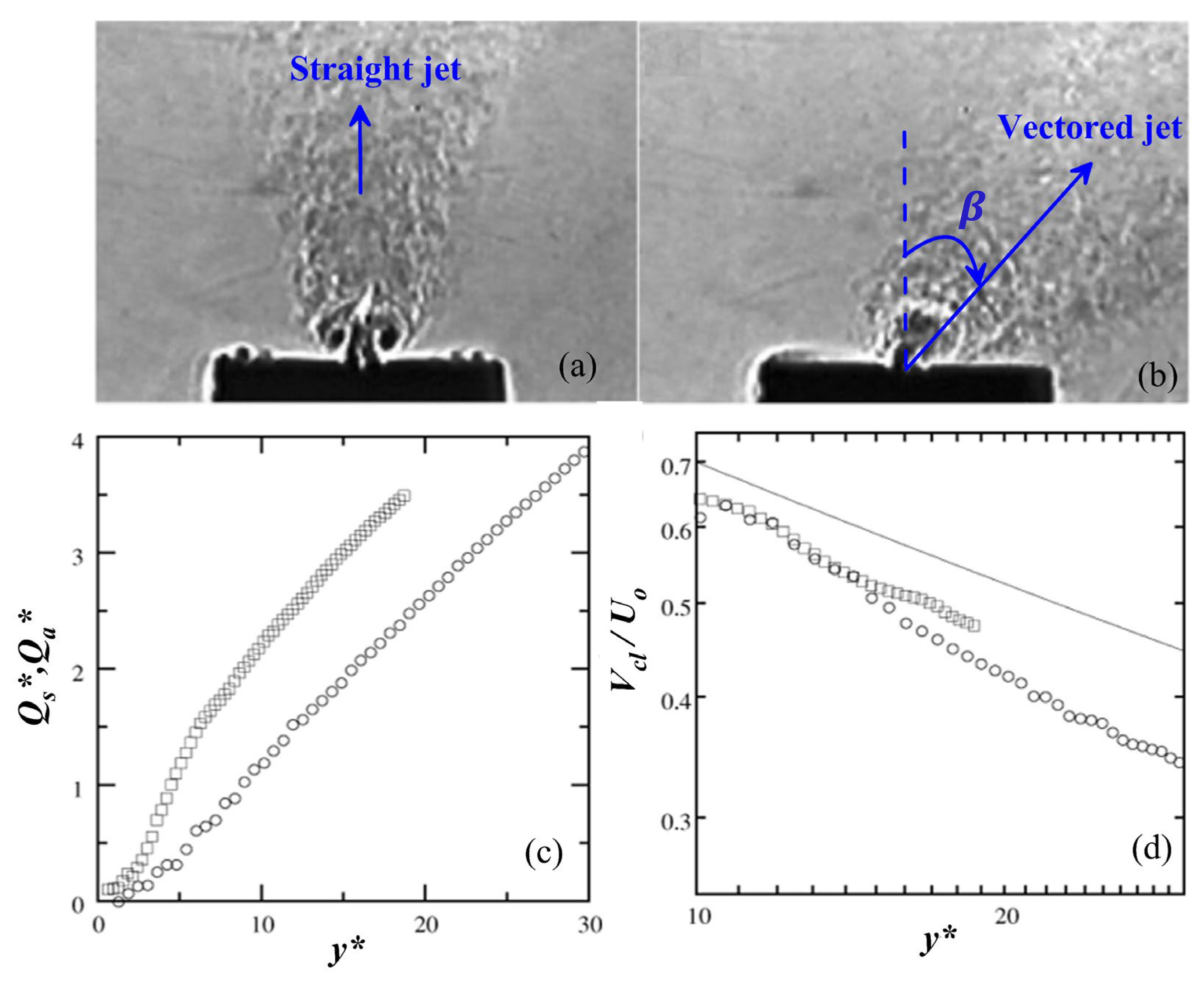

DSJs offer advantages over single-actuator SJs by generating multiple vortices that entrain more surrounding fluid, thereby increasing the volume flow rate [

112]. Additionally, their vectoring capability enables wider spanwise coverage [

112,

152,

153]. However, far-field ineffectiveness remains a key drawback of DSJs. For

0° (

Figure 14a), the counter-rotating inner vortices (1⁺ and 2⁻) lead to significant destructive interference in the near field. This interaction diminishes vortex coherence and results in a noticeable reduction in jet strength downstream [

112]. The centerline velocity decay (

), plotted against the non-dimensional streamwise distance (

), is shown in

Figure 15d. For the single SJA,

, whereas for the DSJ,

2

, where 2

represents the total orifice width of the dual configuration. This scaling is adopted to enable a direct comparison of the streamwise evolution of the single jet and the merged jet pair based on their respective total exit widths [

112]. It can be interpreted from

Figure 15d that, beyond

15, although the DSJs retain a modest advantage in velocity magnitude over the single SJs, both configurations exhibit significant decay.

Figure 15.

Schlieren visualization of DSJ operated at (a)

and (b)

. (c) Streamwise variation (

y*) of normalized volume flow rate for single (

, ○) and DSJs (

, □). (d) Decay of centerline velocity (

) for a single synthetic jet (○) and DSJs (□) operated at

. The solid line shows the

decay law. Reproduced with permission from [

112].

Figure 15.

Schlieren visualization of DSJ operated at (a)

and (b)

. (c) Streamwise variation (

y*) of normalized volume flow rate for single (

, ○) and DSJs (

, □). (d) Decay of centerline velocity (

) for a single synthetic jet (○) and DSJs (□) operated at

. The solid line shows the

decay law. Reproduced with permission from [

112].

Berk et al. [

154] investigated effects of

(171 – 856), Strouhal number (

= 0.02 – 0.12), orifice spacing (

= 2 – 3), and phase difference (

= 100°– 150°) on the flow behavior of DSJs, while maintaining a fixed aspect ratio (

= 13). While the Reynolds number showed limited influence on vectoring, greater

amplified jet deflection. For smaller orifice spacings (

2.2 and 2.4), the vectoring angle increases noticeably with higher phase differences (

Figure 16a). However, these conditions also intensified vortex interactions, diminishing jet momentum. For example, at

= 2.2 and

= 100°– 140°, jet vectoring angle increased by ~31° (

Figure 16a), but the normalized jet momentum flux (

) dropped by nearly 45% (

Figure 16b). Here, the jet momentum flux

is defined as [

154]

Here,

is the air density,

is the normal velocity,

is the radial distance from the origin, and

is the angle measured from the vertical axis. The momentum flux is normalized by

, the reference momentum flux, which is calculated using the time-averaged velocity at the orifice exit. This decline in normalized momentum flux is attributed to enhanced vortex interaction, where destructive interference and the formation of smaller secondary vortices disrupt the primary flow structures [

154]. Similar reductions in jet strength due to strong inner vortex interactions have also been reported at small orifice spacings [

155], with the merged structure mimicking a single jet rather than two distinct sources. For DSJs, research has reported that while cavity geometry has minimal influence on jet dynamics, stroke length and Reynolds number play a crucial role in jet development and deflection [

152]. The influence of phase difference and actuator spacing on the vectoring and mixing characteristics of DSJs in both quiescent and crossflow environments has been extensively investigated [

20,

153,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165,

166,

167,

168].

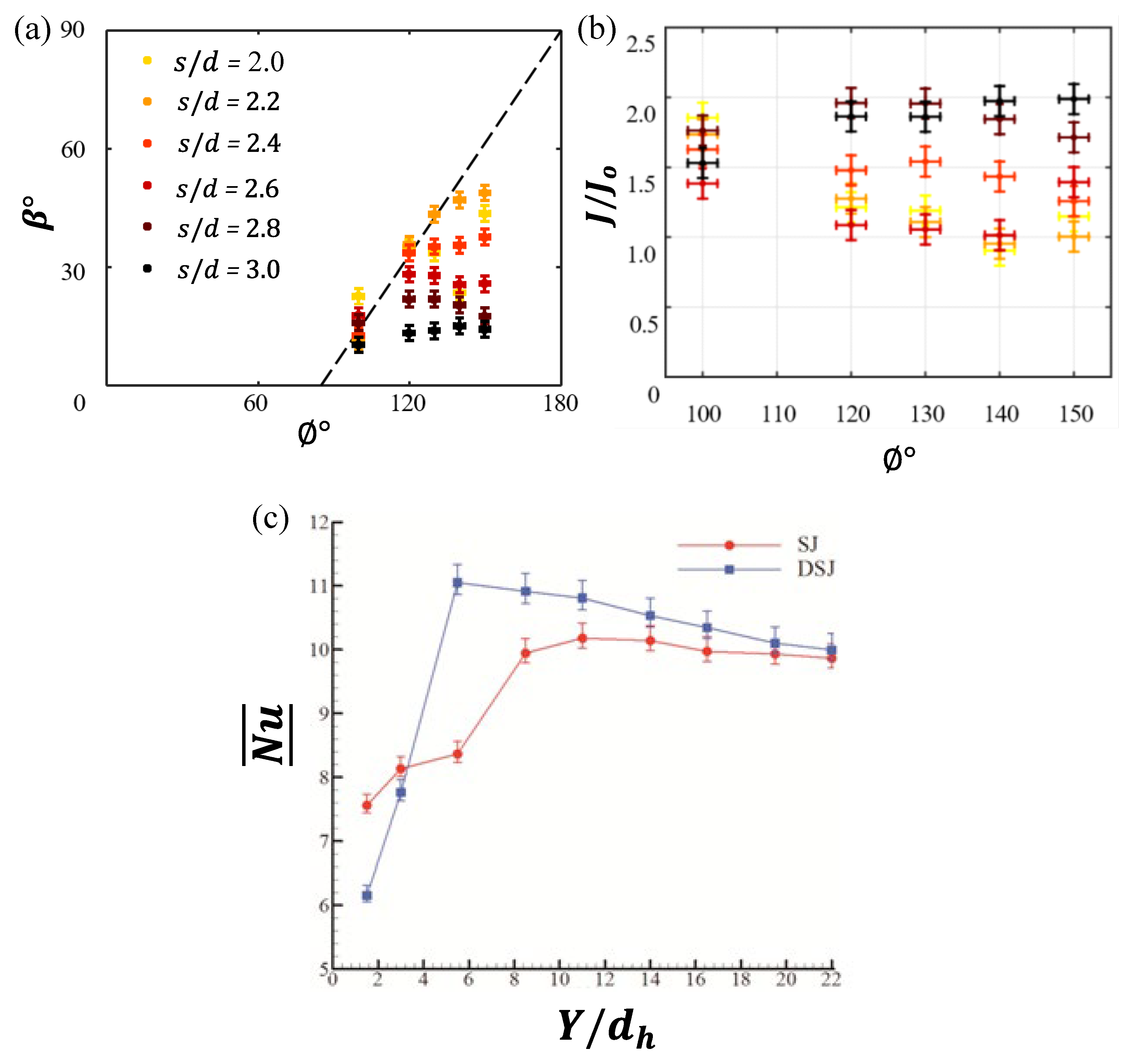

Figure 16.

(a) Vectoring angle (

) and (b) normalized momentum flux (

) as functions of phase difference at

and

, reproduced with permission from [

154]. (c) Comparison of time-averaged and area-averaged Nusselt number

variation with

between a single-actuator SJ and a DSJ, reproduced with permission from [

175].

Figure 16.

(a) Vectoring angle (

) and (b) normalized momentum flux (

) as functions of phase difference at

and

, reproduced with permission from [

154]. (c) Comparison of time-averaged and area-averaged Nusselt number

variation with

between a single-actuator SJ and a DSJ, reproduced with permission from [

175].

DSJs have proven effective in aerodynamic flow control applications due to their ability to generate synchronized or phase-shifted vortex pairs, which enables precise manipulation of boundary layer behavior [

169]. This makes them well suited for delaying flow separation, enhancing lift, and suppressing wake instabilities [

166,

167,

170]. In particular, DSJs have demonstrated greater control effectiveness in managing flow over airfoils and bluff bodies compared to single actuators, owing to enhanced momentum addition [

171].

In heat transfer applications, DSJs operated out of phase have demonstrated improved heat transfer performance compared to in-phase operation [

172,

173,

174]. Specifically, DSJs with phase differences between 60° and 120° show enhanced heat transfer compared to all other phase configurations, primarily due to the vectoring effect and improved mixing characteristics with the surrounding fluid [

174]. Furthermore, in applications requiring localized cooling, such as hot spot mitigation, phase differences between 135° and 180° have been found to be most effective [

174]. The heat transfer benefits of DSJs over single SJs have also been reported in the literature [

128,

175]. At

= 6, the heat transfer enhancement between the DSJ and single SJ is approximately 32% (

Figure 16c) [

175]. However, this enhancement drastically reduces to about 10% at

= 8, with further decrease in performance as

increases (

Figure 16c). This suggests that DSJs exhibit superior heat removal capabilities at lower jet-to-surface distances, facilitated by the formation of twin vortex rings and strong inter-jet interactions, a phenomenon also noted by other researchers [

128]. In the far downstream, DSJs resemble single SJs (

Figure 16c,

> 20), demonstrating their ineffectiveness in the far field. This decline in performance is attributed to extensive vortex diffusion, a phenomenon well documented in the literature [

128,

175].

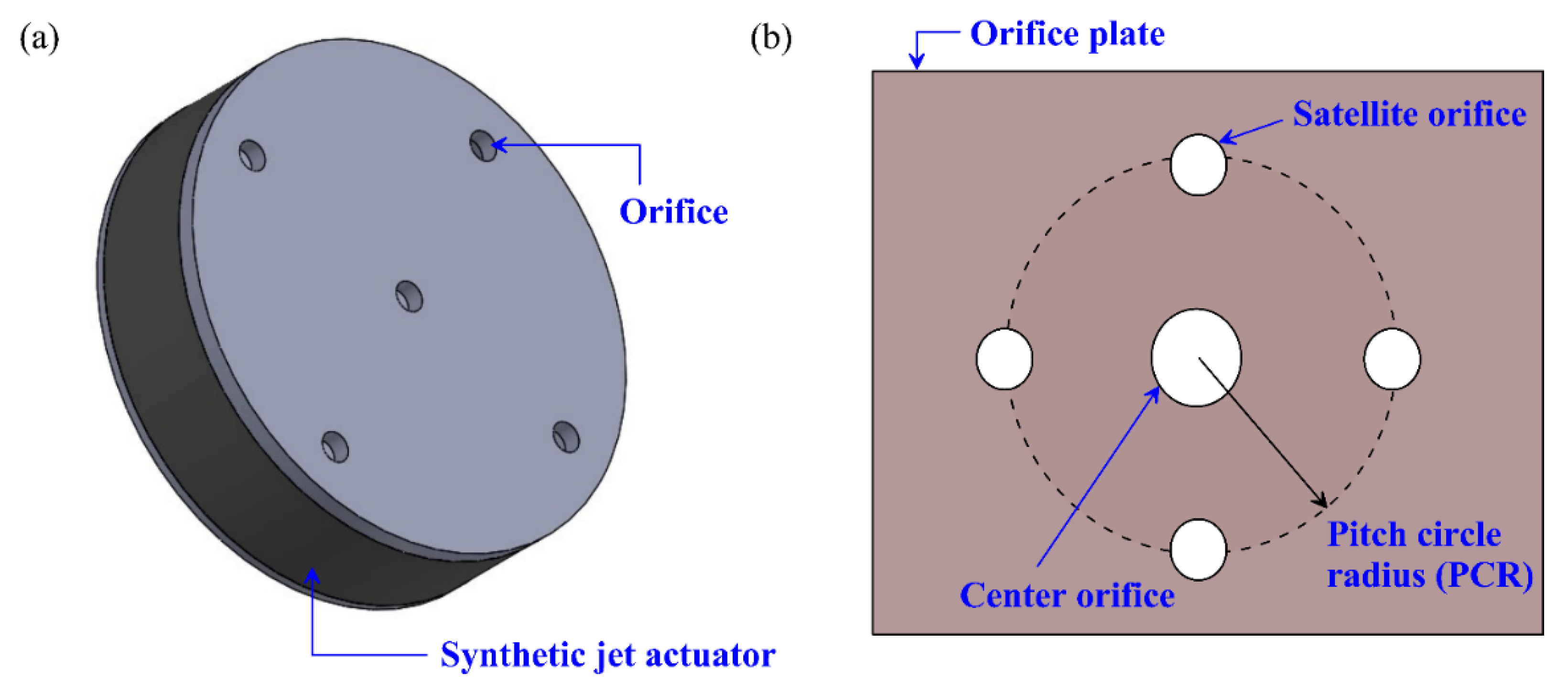

5.2. Single Actuator Multi-Orifice Synthetic Jets

Another advancement in SJ technology is the single actuator multi-orifice configuration (

Figure 17a), in which a single actuator simultaneously drives multiple orifices [

176]. The multi-orifice design, typically featuring a central orifice encircled by satellite orifices (

Figure 17b), enhances fluid entrainment and mixing near the surface, thereby significantly improving convective heat transfer [

176].

Uunder the same jet operating parameters (

= 2600), multi-orifice synthetic jets with the C5 × S3 × 8 configuration (where 5 mm is the diameter of the central orifice, 3 mm is the diameter of the satellite orifices, and 8 is the number of satellite orifices) achieve higher heat transfer than single-orifice synthetic jets (

Figure 18) [

176]. The heat transfer enhancement measured at

= 8 (

Figure 18a) for the C5 × S3 × 8 jets at

= 2600 is approximately 20% percent greater than that of conventional single-orifice synthetic jets with an 8 mm diameter under identical conditions (

= 2600) [

176]. For the same hydraulic diameter (

=

= 14 mm) and the same operating parameters (

= 125 Hz and

= 4 V), the heat transfer enhancement achieved with multi orifice synthetic jets, compared to a single orifice, is also observed along the spanwise direction in the near field (

= 2) (

Figure 19a) [

150]. Research has also reported that a configuration consisting of a central orifice surrounded by satellite orifices provides improved cooling performance for compact electronic components that require localized heat dissipation [

176]. Interestingly, such heat transfer enhancements occur without increasing input power. The multi-orifice configuration can slightly reduce power consumption compared to single-orifice actuators [

176].

Figure 17.

Schematic representation of a multi-orifice synthetic jet actuator: (a) 3D view of a synthetic jet actuator with five circular orifices, and (b) front view of the orifice plate illustrating the central and satellite orifices arranged along a defined pitch circle radius (PCR).

Figure 17.

Schematic representation of a multi-orifice synthetic jet actuator: (a) 3D view of a synthetic jet actuator with five circular orifices, and (b) front view of the orifice plate illustrating the central and satellite orifices arranged along a defined pitch circle radius (PCR).

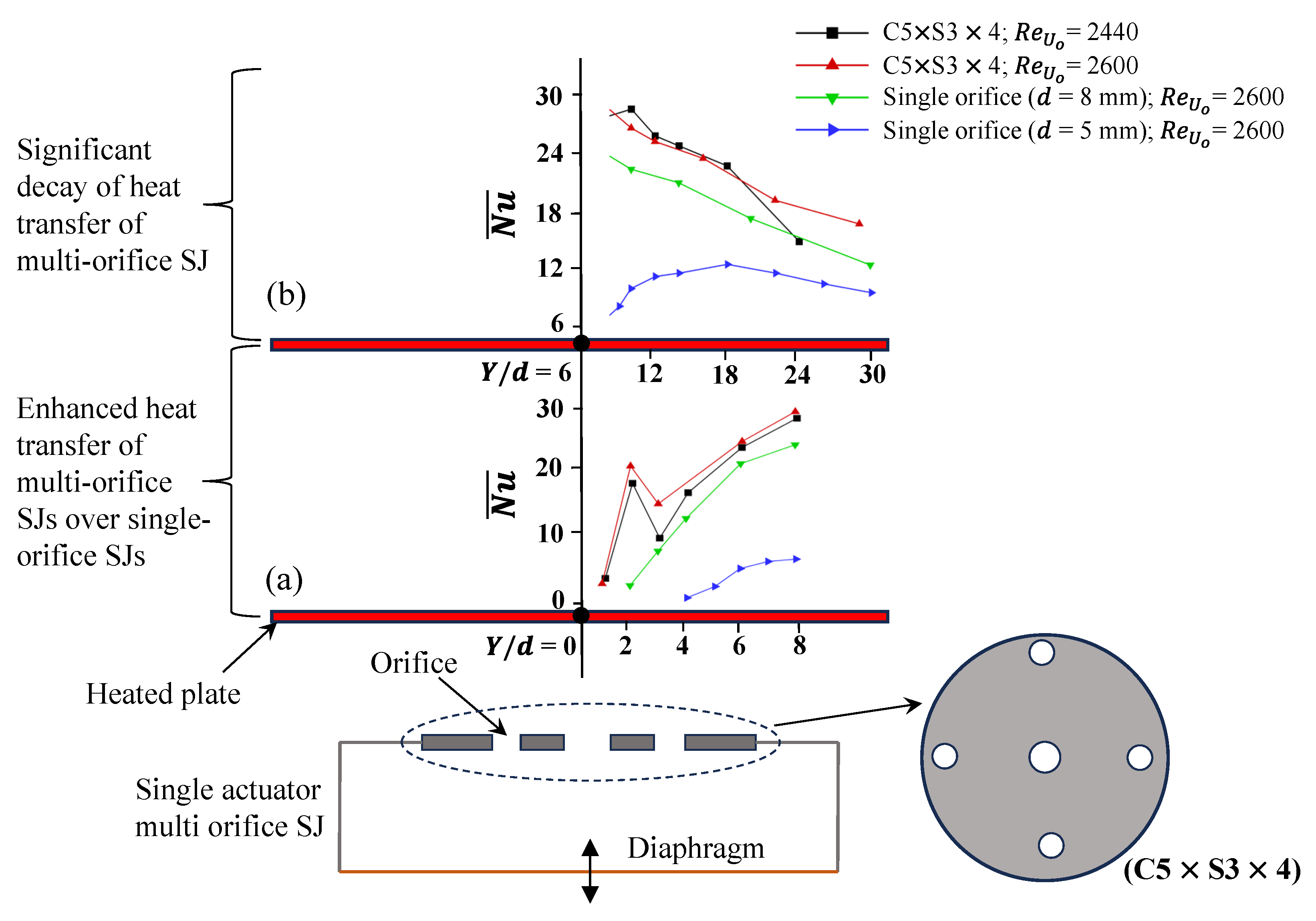

Figure 18.

(a) Variation of

with

showing (a) heat transfer enhancement of multi-orifice synthetic jets over single-orifice, and (b) significant performance degradation of multi-orifice SJs in the far field. Data derived from [

176]. Configuration C5 × S3 × 4 denotes center orifice diameter × satellite orifice diameter × number of satellite orifices.

Figure 18.

(a) Variation of

with

showing (a) heat transfer enhancement of multi-orifice synthetic jets over single-orifice, and (b) significant performance degradation of multi-orifice SJs in the far field. Data derived from [

176]. Configuration C5 × S3 × 4 denotes center orifice diameter × satellite orifice diameter × number of satellite orifices.

When integrated into electronic cooling systems such as heat sinks, multi-orifice synthetic jets have demonstrated superior thermal performance [

17,

177]. During impingement on the heat sink surface, these jets showed a 12% increase in the maximum heat transfer coefficient compared to single-orifice jets, and an overall heat transfer enhancement nearly six times greater than that achieved by natural convection [

177]. Despite these benefits, multi-orifice jets, like single-orifice SJs, exhibit ineffective performance in the far field [

176]. For example, the

for satellite orifices (C5

3

4) at

= 2440 decreases by approximately 50% between

= 10 and 24 (

Figure 18b), which Chaudhari et al. [

176] attributed to rapid vortex diffusion in the far downstream region. This decline in far field performance has been observed across various multi-orifice shapes, including circular, oval, and diamond configurations, as well as different waveforms [

91,

178,

179,

180]. It is worth mentioning that the spanwise heat transfer enhancement of the multi orifice synthetic jets, compared to the single orifice jet observed in the near field (

= 2) (

Figure 19a), is no longer present at

= 6 (

Figure 19b) [

150]. At

= 6, the interaction between the central and satellite vortices breaks into smaller vortical structures before they can fully develop [

150]. As a result, the radial cooling advantage of multi orifice jets diminishes and becomes comparable to, or even weaker than, that of single orifice configurations (

Figure 19b). This suggests that the performance benefits of multi orifice arrangements are primarily limited to the near field [

150].

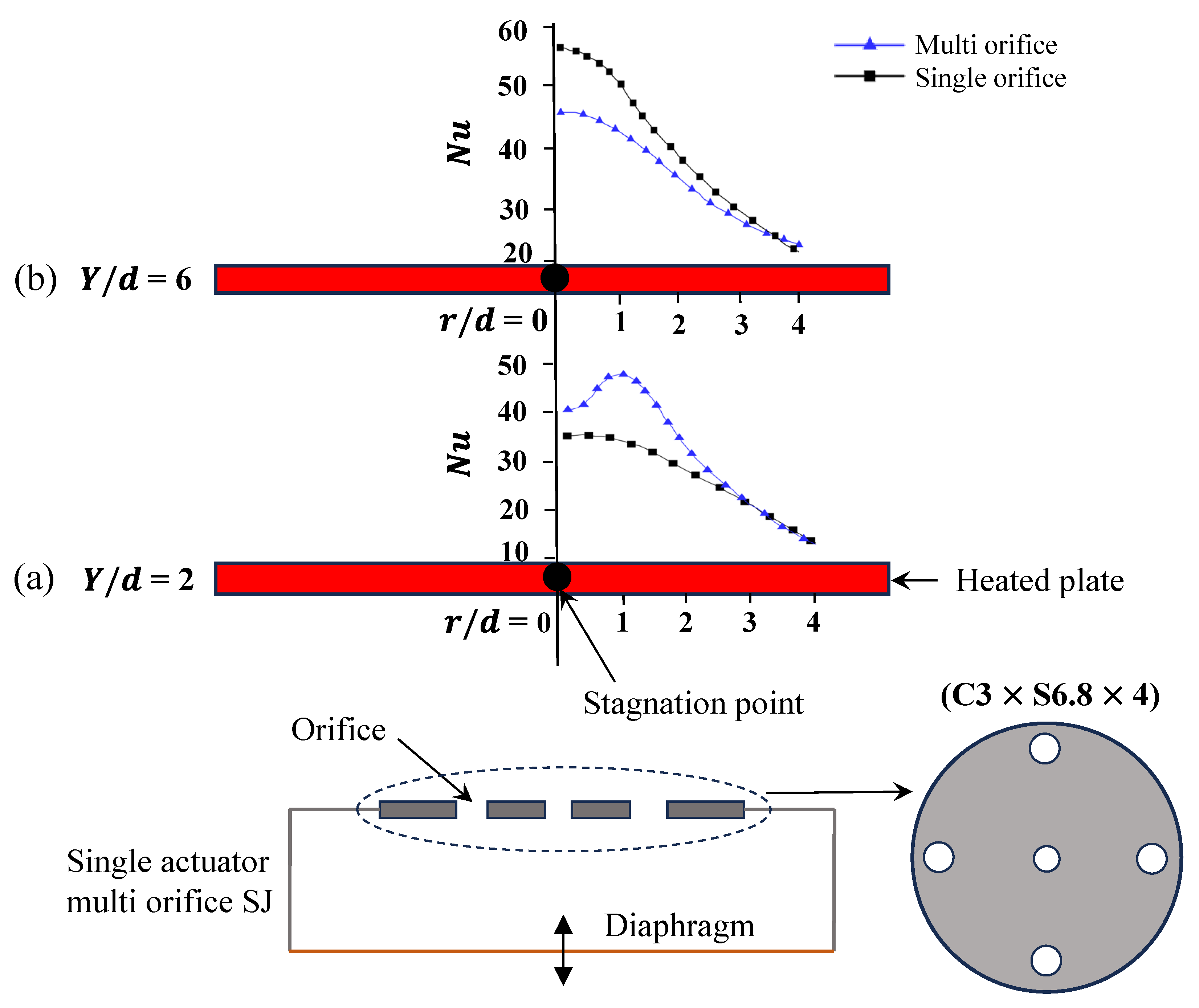

Figure 19.

Comparison of local Nusselt number distribution along the radial direction between multi-orifice synthetic jets and single-orifice SJs with the same hydraulic diameter of 14 mm, operated at 125 Hz frequency and 4 V amplitude, at (a)

= 2 and (b)

= 6, based on data from [

150].

Figure 19.

Comparison of local Nusselt number distribution along the radial direction between multi-orifice synthetic jets and single-orifice SJs with the same hydraulic diameter of 14 mm, operated at 125 Hz frequency and 4 V amplitude, at (a)

= 2 and (b)

= 6, based on data from [

150].

5.3. Coaxial Synthetic Jets (CSJs)

Coaxial synthetic jets, another technological advancement based on their structural configuration and actuation method, are categorized into three types: (a) double acting synthetic jets with concentric cavities driven by a common actuator (

Figure 20); (b) concentric orifice single-actuator synthetic jets, which use one actuator to supply multiple concentric orifices (

Figure 22); and (c) independently controlled coaxial synthetic jets, featuring separate actuators for each element (

Figure 23).

5.3.1. Double Acting Synthetic Jets (DASJs)

In the DASJ configuration, both the inner and annular cavities are actuated by a common mechanism operating in anti-phase (∅ = 180°). During one half-cycle, the inner cavity expels fluid while the annular cavity simultaneously draws it in (

Figure 20a). This flow pattern reverses in the subsequent half-cycle, with the annular cavity ejecting fluid and the inner cavity inducing suction (

Figure 20b). The phase-opposed operation induces dynamic interactions between the core flow and surrounding vortical structures, substantially influencing the jet development [

12].

Figure 20.

Operating principle of a DASJs showing (a) ejection from the inner cavity and suction into the annular cavity during the forward stroke, and (b) suction from the inner cavity and ejection from the annular cavity during the backward stroke.

Figure 20.

Operating principle of a DASJs showing (a) ejection from the inner cavity and suction into the annular cavity during the forward stroke, and (b) suction from the inner cavity and ejection from the annular cavity during the backward stroke.

DASJs produce significantly higher vorticity than single jets while exhibiting a noticeably narrower jet profile [

12]. The velocity field remains strongly centered along the axis a result of increased inward entrainment induced by the annular flow component, which sharpens the jet and helps maintain its coherence further downstream [

12]. Therefore, despite the enhanced jet strength, the narrower profile of DASJs may limit their effectiveness in applications requiring broader surface coverage. To address this limitation, researchers modified the geometric configuration of DASJs [

181]. Ahmed and Bangash [

181] reported that for DASJs, when the radial spacing (

) between the inner orifice and the outer annular opening (as shown in

Figure 20b) is maintained at 1

, the jet width is significantly enhanced compared to a single orifice SJ. This demonstrates a strong potential to mitigate the confinement effect typically observed in single actuator synthetic jets, which are characterized by narrower jet profiles [

181]. Further studies revealed that DASJ performance is highly sensitive to the operating parameters of the actuators [

181,

182].

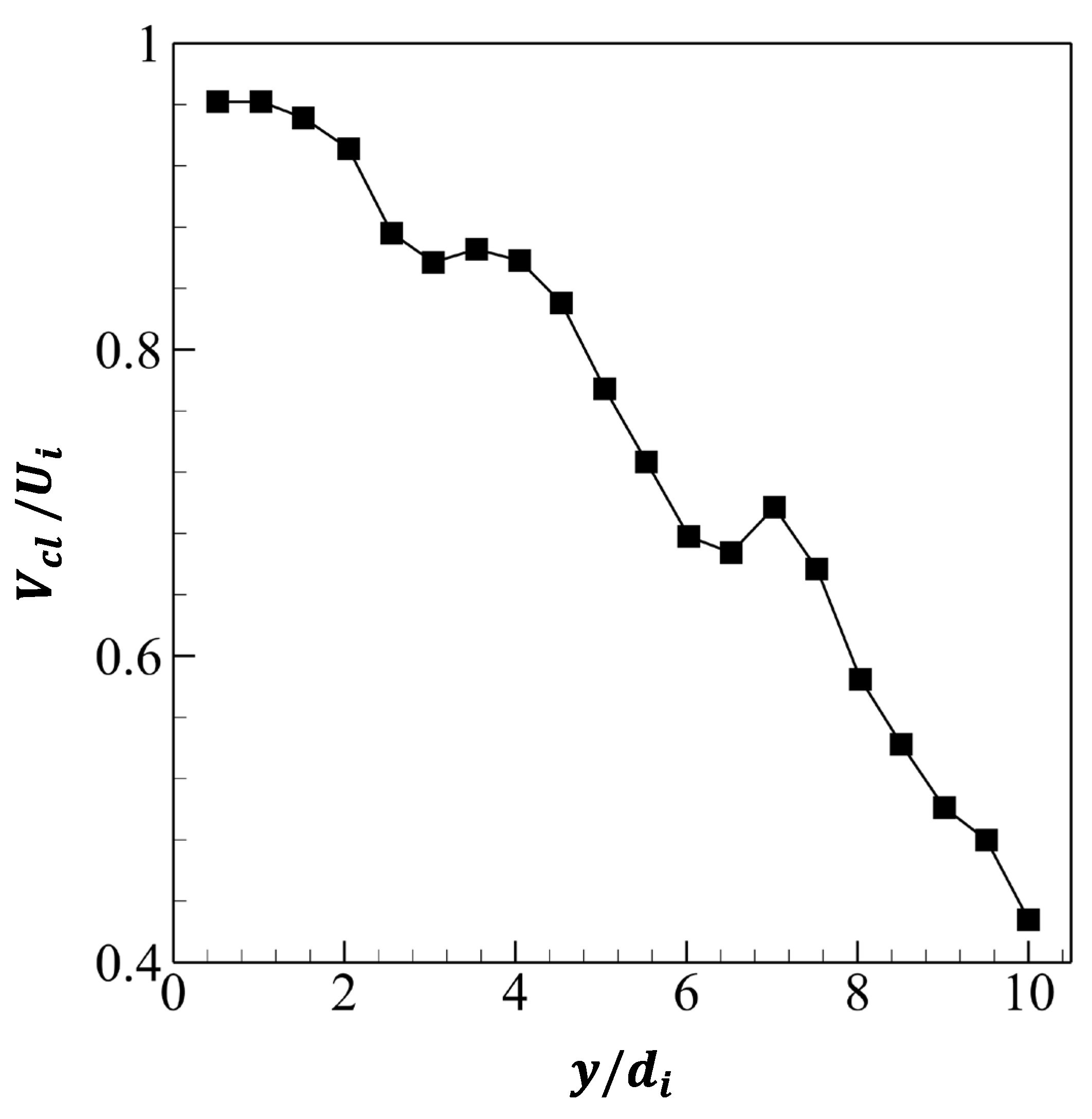

While manipulating the design and operating parameters of DSJs enhances jet spreading [

181], this improvement often comes at the expense of a significant reduction of the centerline velocity (

Figure 21) [

59]. Specifically, the centerline velocity

decreases by approximately 56% between

= 0.5 and

= 10 (

Figure 21), where

and

are the time-averaged velocity and diameter measured at the inner orifice exit, respectively [

59]. This reduction is due to the weakening of vortex structures downstream [

59,

181].

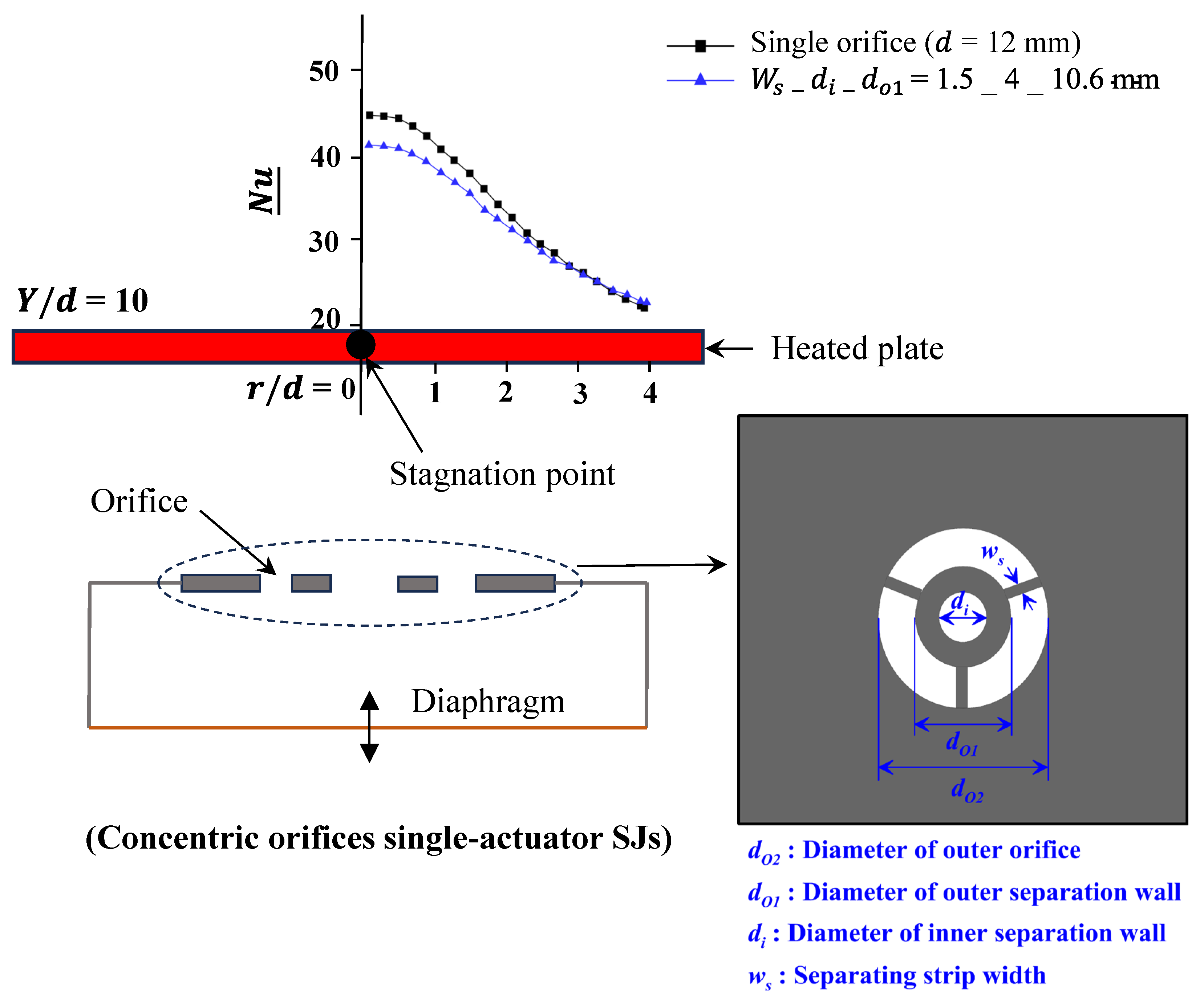

5.3.2. Concentric Orifices Single-Actuator Synthetic Jets (COSASJs)

In the COSASJs configuration (

Figure 22), both the inner and outer orifices operate simultaneously, generating coordinated vortex structures that enhance jet formation and increase the overall flow volume [

183]. Studies employing infrared thermography and smoke wire visualization across various Reynolds numbers, actuation amplitudes, and orifice-to-surface spacings have demonstrated significant improvements in convective heat transfer when this configuration operates in close proximity to the heated surface [

183]. Research reported that at smaller spacings (

= 2), the COSASJ configuration with dimensions 1.5_4_10.6 (where

= 1.5 mm,

= 4 mm, and

= 10.6 mm) achieves an approximately 20% increase in the time- and area-averaged Nusselt number (

) compared to conventional single-orifice synthetic jets of 12-mm diameter [

183]. The equivalent diameter

used for normalization is defined such that the total discharge area of the coaxial configuration equals the area of a 12-mm single orifice [

183]. The enhancement in

for the COSASJ at

= 2 is primarily attributed to independent vortex generation from the inner and outer orifices, which strengthens local mixing, disrupts the thermal boundary layer, and suppresses hot-air recirculation near the heated surface [

183].

However, for

≥ 6, the thermal performance of COSASJs begins to deteriorate, becoming lower than that of single-orifice jets [

183]. This decline is attributed to rapid vortex energy dissipation, which weakens momentum transport in the far field and reduces the effectiveness of jet-surface interaction [

183]. A similar trend is observed in the radial distribution of heat transfer (

Figure 22), where COSASJs demonstrate inferior performance compared to single-orifice jets at

= 10 [

183].

Figure 22.

Comparison of time-averaged Nusselt number distribution along the radial direction between COSASJs and single-orifice SJs with the same hydraulic diameter of 12 mm, operated at

5830 at

= 10, based on data from [

183].

Figure 22.

Comparison of time-averaged Nusselt number distribution along the radial direction between COSASJs and single-orifice SJs with the same hydraulic diameter of 12 mm, operated at

5830 at

= 10, based on data from [

183].

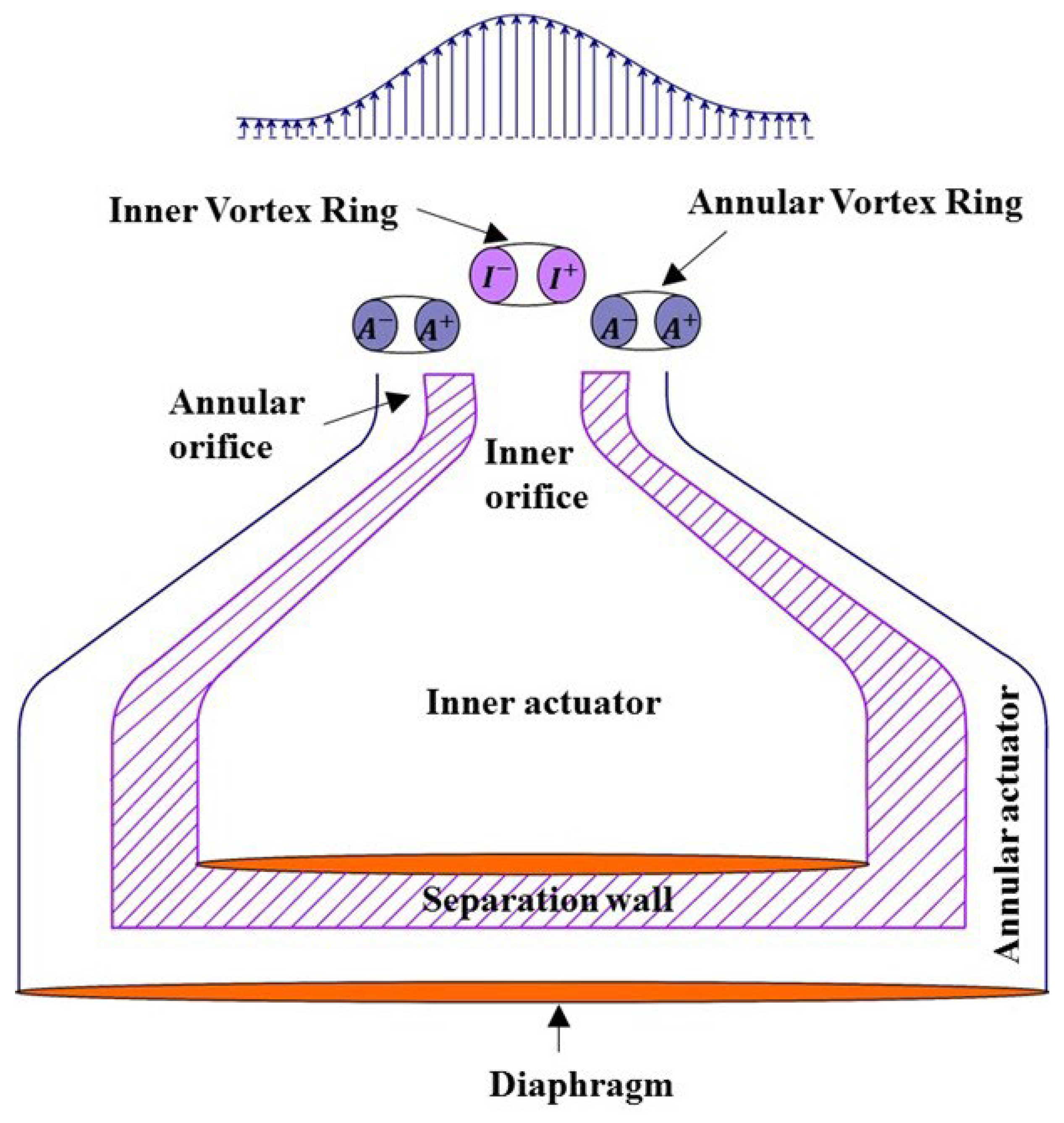

5.3.3. Independently Controlled Coaxial Synthetic Jets (IC-CSJs)

Among all coaxial synthetic jet configurations, independently controlled coaxial synthetic jets (

Figure 23) stand out for their ability to precisely regulate frequency, amplitude, and phase of each actuator separately, enabling fine-tuned control over jet behavior [

184]. Such independent control enables precise modulation of vortex interactions, leading to more efficient momentum transfer and enhanced entrainment [

16,

184]. The flow dynamics of IC-CSJs involve the formation, evolution, and interaction of the inner vortex ring (IVR) generated by the inner actuator and the annular vortex ring (AVR) formed by the annular actuator [

184,

185]. In a two-dimensional representation, the annular actuator produces a pair of counter-rotating vortices, denoted as

and

, corresponding to anticlockwise and clockwise rotations, respectively, while the inner actuator generates vortices

and

with the same rotational convention (

Figure 23). The dynamics of these vortex structures under varying jet operating conditions have been extensively reported in the literature [

184,

185].

Figure 23.

Schematic of IC-CSJs illustrating key components.

Figure 23.

Schematic of IC-CSJs illustrating key components.

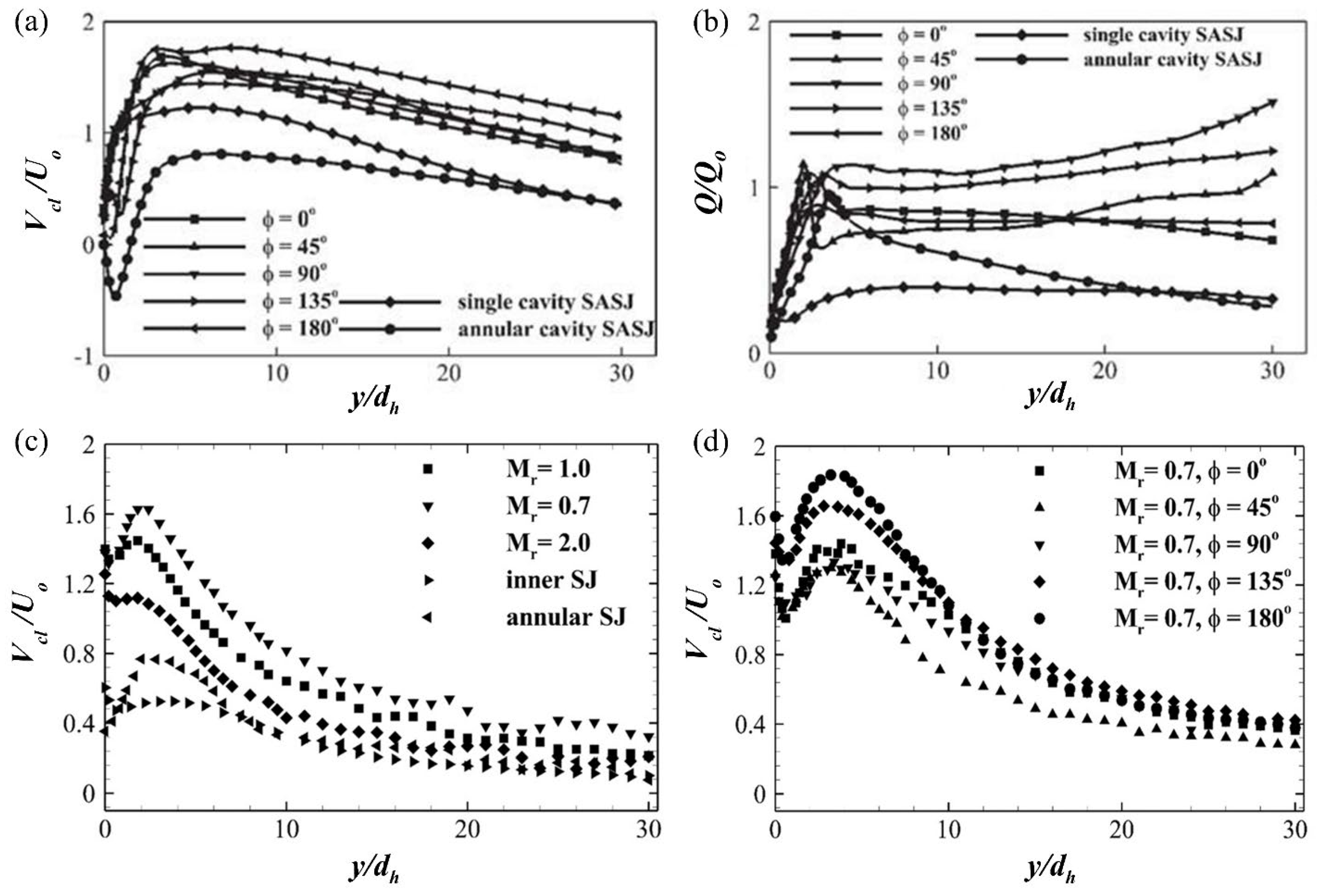

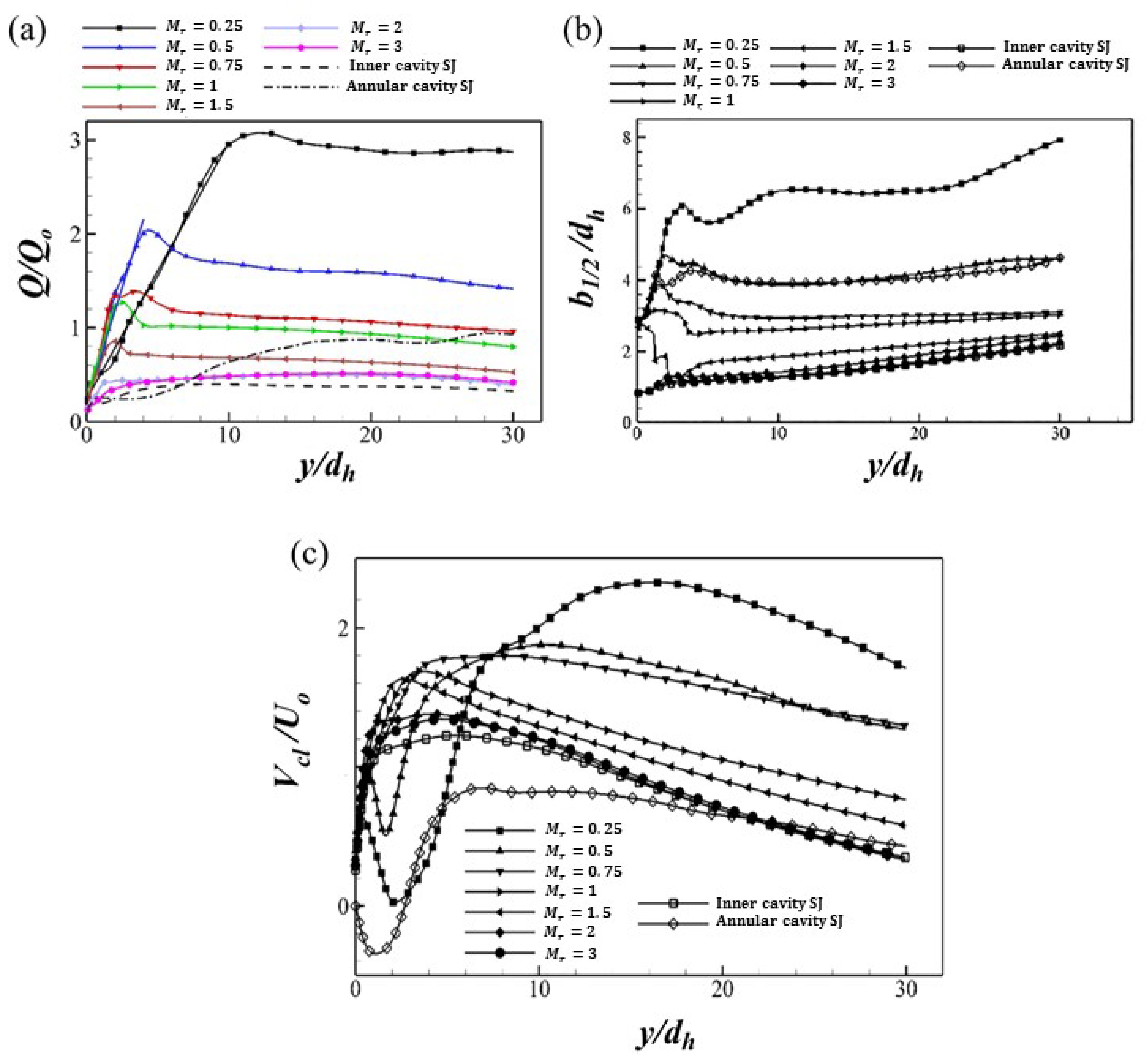

A crucial parameter governing IC-CSJ behavior is the mass flux ratio (

), defined as the ratio of the mass flux of the inner jet (

) to that of the annular jet (

) [

184]. The mass flux for each jet is expressed as

=

and

=

, where

and

are the time-averaged velocities of the inner and annular jets, respectively. This ratio is typically varied by modifying the annular jet's frequency and amplitude of oscillation [

184]. Panda et al. [

184] performed a detailed numerical investigation at

= 150 to examine the influence of mass flux ratio (

0.25

3) on the flow behaviour of IC-CSJ and compared the results with those of independently operated inner and annular actuators. According to their findings, when the IC-CSJ is operated at the lower end of this range (

0.25), the resulting jet exhibits superior flow characteristics compared to other mass flux ratios, as well as to the inner and annular jets operating individually (

Figure 24). Specifically, the jet maintains a stronger volume flux (

) throughout the streamwise domain (

Figure 24a), a wider half-width (

) (

Figure 24b), and a significantly higher centerline velocity (

Figure 24c). For the three-dimensional simulated case, the detailed methodology for estimating the volume flux and jet half-width has been comprehensively documented in the literature [

184]. Here, the hydraulic diameter (

) is maintained at 1.5 mm for both the inner and annular orifices [

184]. The enhanced volume flux corresponds to the generation of a larger flow rate, while the wider jet half-width and higher centerline velocity indicate greater spanwise coverage and sustained jet strength in the far field, respectively, for IC-CSJs compared to single-actuator synthetic jets [

184]. The enhanced performance of the IC-CSJ at the lower mass flux ratio (

0.25) arises from an effective interaction between the strong annular jet momentum and the inner jet, which promotes intensified vortex interactions, improved mixing, and a coherent, sustained jet structure [

184].

This advantage becomes even more pronounced when the phase difference between the actuators is varied [

185]. Introducing a phase difference between the inner and annular jets, where the annular jet leads in phase relative to the inner jet, facilitates constructive vortex interactions [

185]. For instance, at

180°, vortex pairing enhances the coherence and strength of the jet core, while intermediate phase differences such as

90° and 135° induce azimuthal instabilities that enhance entrainment and volumetric growth [

185]. The progressive increase in centerline velocity and jet volume flux with increasing

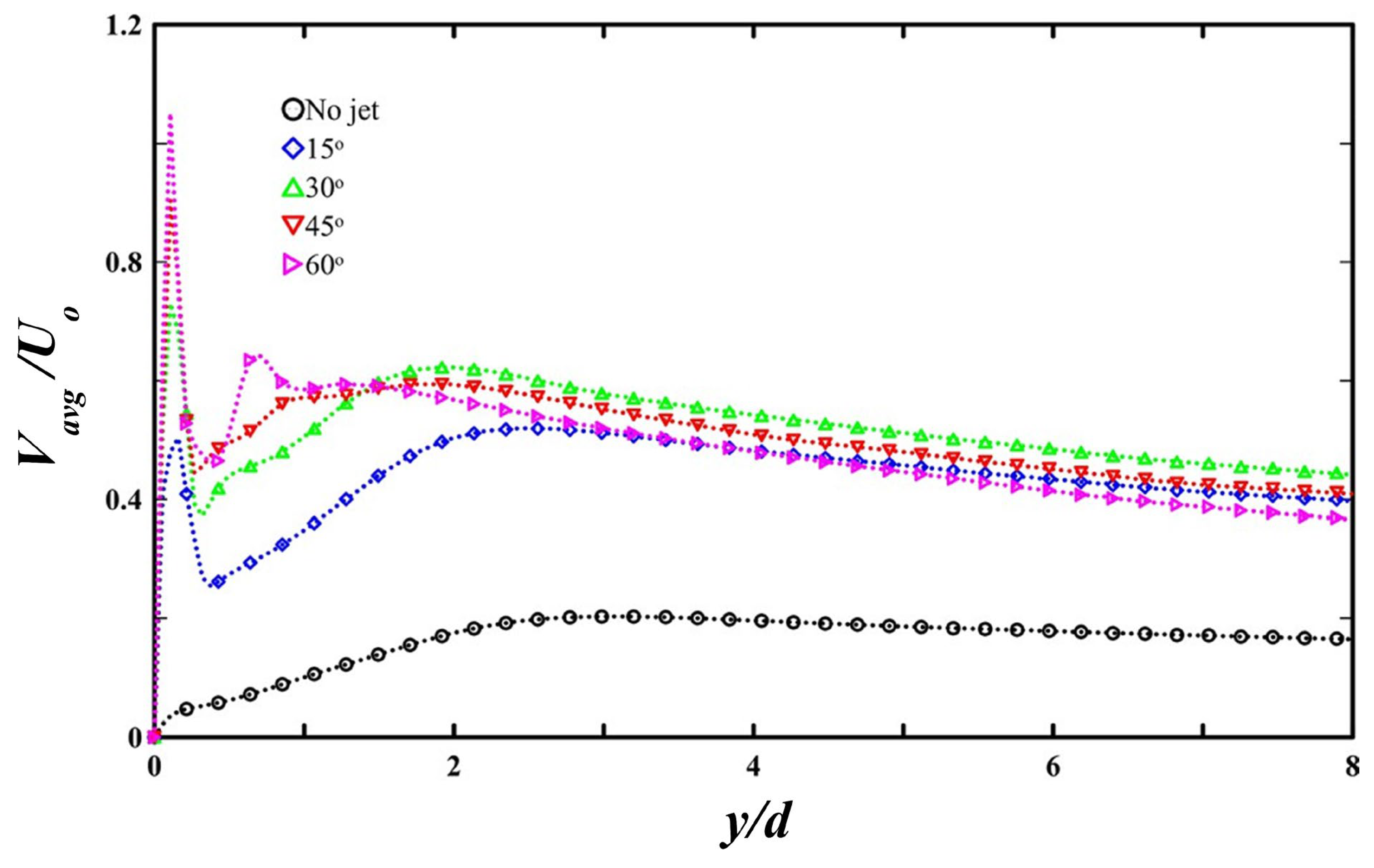

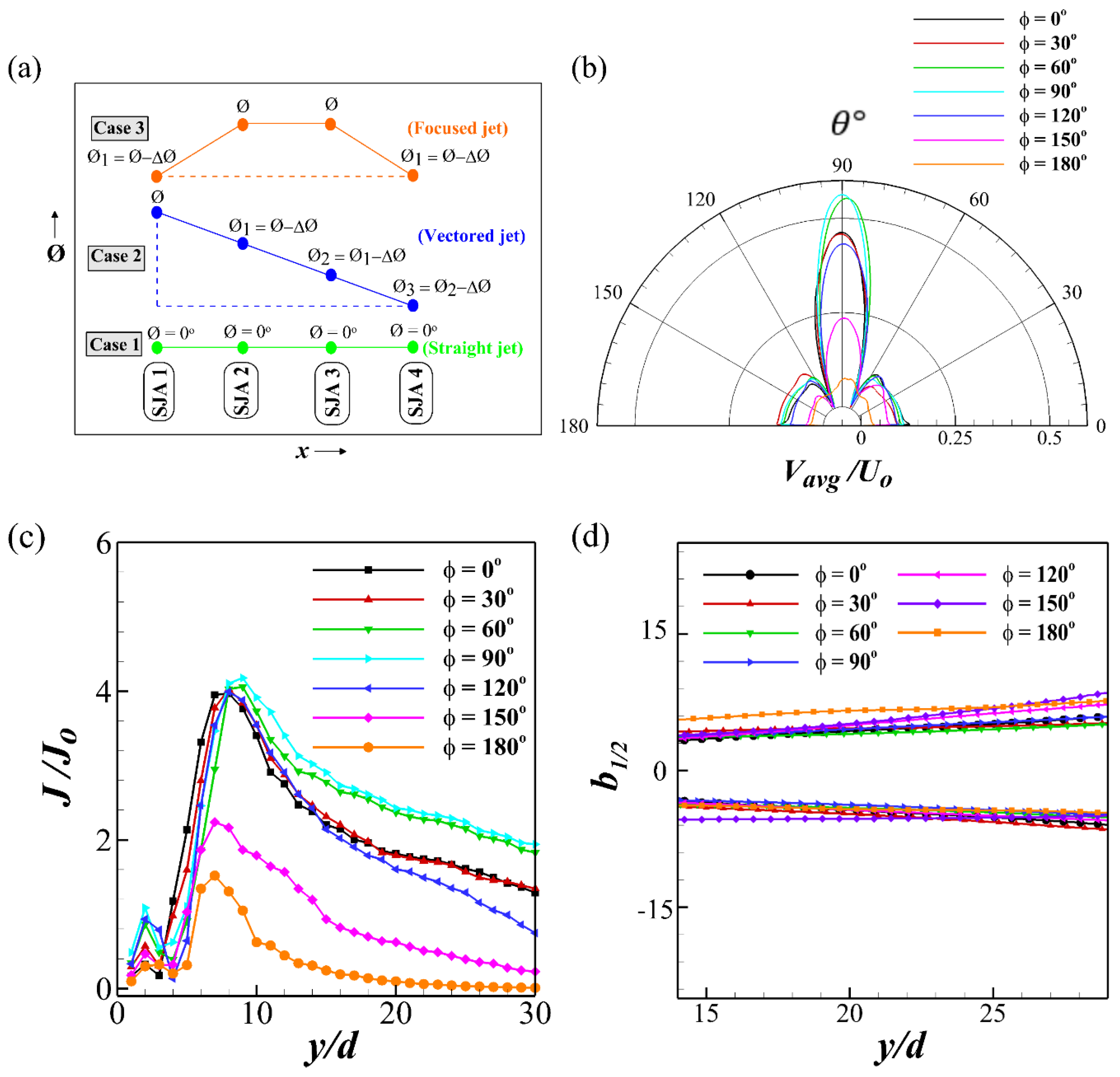

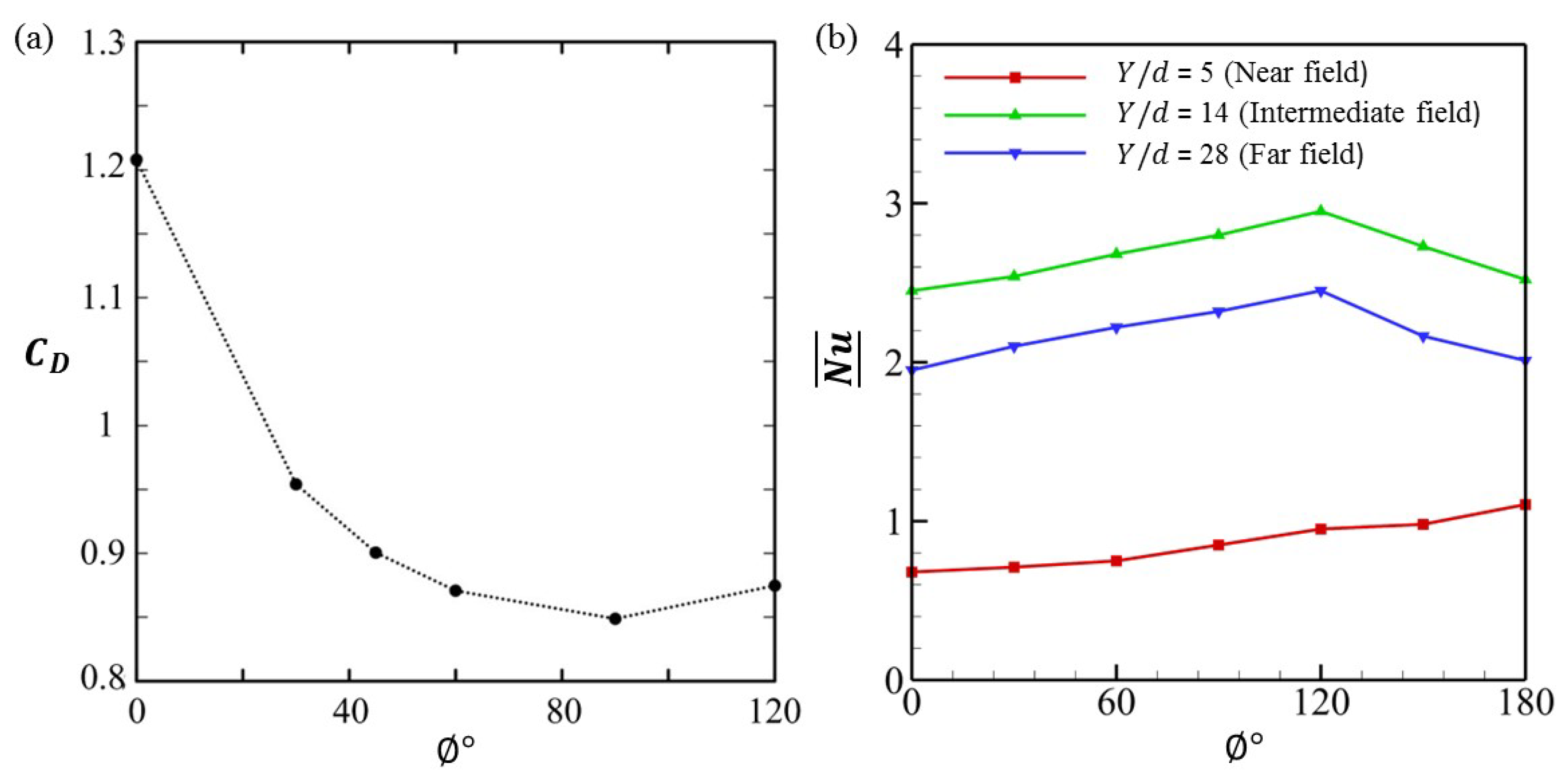

is evident in