1. Introduction

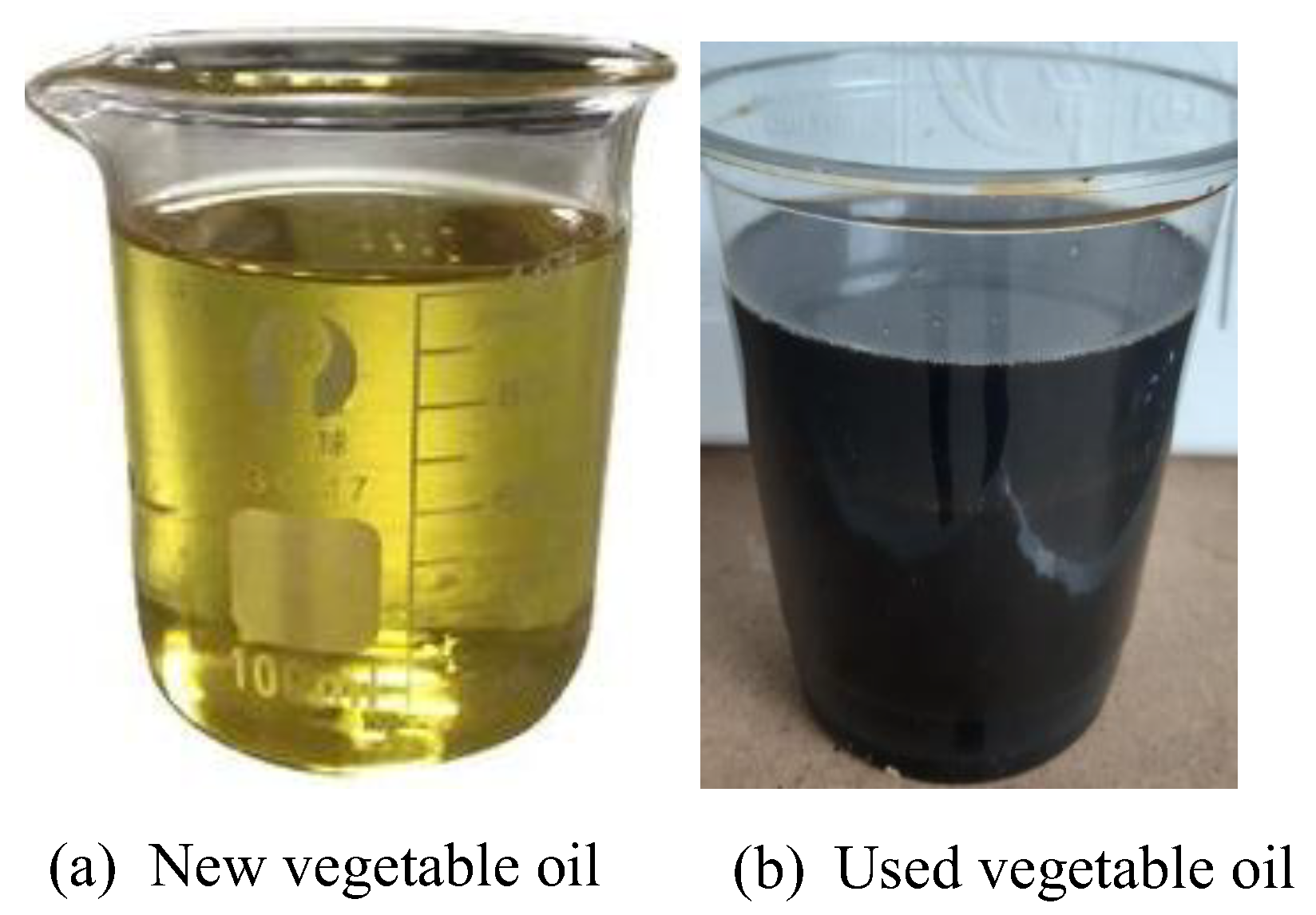

Many household and commercial activities produce crude glycerol and used vegetable oil, which are major waste products. This is especially true in the biodiesel manufacturing and food industries. The key to optimal management and use is a good grasp of their features, applications, and environmental impacts.

A thick, colorless, and very hydrating liquid, crude glycerol is a byproduct of the transesterification process used to make biodiesel. Its purity and possible uses are affected by the presence of contaminants, including methanol, soap, free fatty acids, and excess catalysts. Raw glycerol must be refined before it can be used in many sectors due to its chemical composition. Inadequate disposal and management of crude glycerol pose environmental risks. One way to reduce trash and make the world a better place is to recycle and repurpose materials. Discarded vegetable oil, sometimes called waste cooking oil, is produced by commercial, industrial, and residential kitchens every day. The presence of food remnants, free fatty acids, and other contaminants makes its disposal a challenge. Avoiding pollution, particularly that which contaminates water and degrades soil, requires careful collection and treatment. To prevent pollution and unlawful disposal, it is important to establish procedures for collecting spent vegetable oil and properly storing it. In addition to reducing landfill waste, recycling used oil helps preserve valuable resources and lessens our impact on the environment by recovering usable energy.

A wide variety of companies can benefit from both crude glycerol and used vegetable oil, two significant commodities. Their efficient use and management help reduce waste, protect the environment, and promote sustainable development. In line with a circular economy strategy, advances in processing technologies are increasing the possibility of turning these waste products into valuable commodities. Regarding glycerol and used vegetable oil, several studies exist.

Reed et al. [

1] created and evaluated M-Diesel, a substitute diesel fuel. Produced from used vegetable oils, it solves the problems of the high cost and thick consistency of traditional vegetable oil fuels. M-Diesel, created from recycled vegetable cooking oils, is an abundant resource; the United States alone produces 350 million gallons per year. Waste oil and sodium hydroxide in methanol are mixed during the transesterification process to produce Fuel. The process of cleaving fat molecules and removing their glycerin yields fatty acid esters. Vegetable oil undergoes a process called transesterification that makes it as thin as regular diesel fuel. Raw vegetable oils may form carbon deposits and are 20 times thicker than diesel; this eliminates a major problem of these fuels. M-Diesel has a 95% greater heat of combustion than conventional diesel, measured in cubic centimeters. The cetane number is also high, ranging from 50 to 80, which is significantly higher than diesel's typical value of 42. Çetinkaya et al. [

2] used base-catalyzed transesterification to enhance biodiesel synthesis from cooking oil leftovers received from restaurants. Conditions for reactions and refinement were investigated. The research found the best way to make biodiesel from used cooking oil. Biodiesel's production costs are reduced and its market position is improved when it uses inexpensive feedstock like this oil. How the amount of glycerin impacts the refinement quality of biodiesel was also investigated in the study. In order to selectively oxidize glycerol, Kaminski et al. [

3] used catalysts that were composed of copper and gold. The development, characterization, and use of mesoporous cerium-zirconium oxide as a substrate for copper and gold species were accomplished. When it came to glycerol oxidation activity and selectivity toward glyceric acid, bimetallic copper-gold catalysts performed better than monometallic gold catalysts. Catalysts composed of two metals exhibit remarkable stability. When used in alkaline glycerol oxidation, they improved the selectivity for glyceric acid. Transesterification of biodiesel, glycerol, and methanol was performed by Rubianto et al. [

4] to produce a sustainable liquid fuel. An external combustion engine was used to test biodiesel blends with glycerol and methanol in ratios ranging from 1:1:1 to 1:1:4 (v/v). An important discovery was that combustion was easier to achieve by adding more methanol to the mixture. A 1:1:4 volume ratio of biodiesel, glycerol, and methanol was the best boiler burner mix.

The performance and emissions of an unmodified diesel engine running on WCOB were examined by Samanta et al. [

5]. Biodiesel is a viable alternative to petroleum diesel to help mitigate rapid climate change and global warming driven by diesel engine emissions. Transesterification efficiently produces biodiesel from waste cooking oil. This technique can be accelerated with a 55 °C alkali catalyst. The investigation focused on an unmodified stationary diesel engine running on a B10 blend of 10% WCOB and petroleum diesel (B0). At 1500 rpm, experiments were run with 0%, 25%, 50%, and 100% load. The engine performed poorly at mid- to high-load conditions on B10 WCOB. Jensani et al. [

6] observed that co-digestion of food waste and crude glycerol works in experiments. This co-digestion method may boost biogas production. Treatment of food waste and crude glycerol is done in addition to biogas production. The study concluded that anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and crude glycerol increases biogas production and solves waste management issues. Elgharbawy et al. [

7] examined the challenges and solutions for producing biodiesel at a lower cost, particularly using waste feedstocks. Relying on edible feedstocks increases competition for food supplies and drives up food prices. Using inexpensive waste feedstocks, such as wasted cooking oil, lowers biodiesel production costs. Waste feedstocks can include large quantities of free fatty acids. High FFA levels react with base catalysts during transesterification, generating soap and lowering biodiesel quality. The study reveals that glycerolysis can pretreat high-FFA waste feedstocks, enabling the use of cheaper raw materials and the production of biodiesel at a lower cost by overcoming the challenges posed by high FFA concentrations. Kurdi et al. [

8] demonstrated and assessed the transesterification of waste cooking oil to produce biodiesel. Transesterification turned leftover cooking oil into biodiesel. Methanol reactant and HCl catalyst were utilized. The oil was transesterified at 90°C for 9 hours using 1:4 methanol-to-oil and 1% HCl by weight. Two hot-water (70°C) washes removed alcohol, catalysts, soap, glycerin, and fatty acid methyl esters from biodiesel.

In conclusion, a transesterification process was employed to manufacture biodiesel from waste cooking oil and to evaluate its physical and chemical properties, thereby demonstrating its energy potential. Lima et al. [

9] described how chemical and biological catalysts convert residual glycerol. The catalytic approach used to convert glycerol into industrial commodities must be carefully evaluated and selected. In conclusion, residual glycerol can be valorized through chemical and biochemical routes to produce a range of high-value products for various industries, with the right catalysts optimizing these conversion processes. Kumar et al. [

10] found that intermittent feeding of municipal sludge (30 g/L of solids) and pure glycerol increased biomass and lipid content. It had 54.99 g/L biomass and 25.35 g/L lipids after 96 hours. This approach significantly reduced fermentation foaming and the need for anti-foam. Municipal sewage helps produce biodiesels and microbial lipids. Intermittent sludge feeding created energy-positive biodiesel. An energy balance analysis for one tonne of biodiesel produced with intermittent sludge feeding (30 g/L SS) showed a positive net energy gain of 22.65 GJ/tonne FAMEs and an energy ratio of 1.41. The technique's high energy ratio and positive net energy gain indicate economic viability. The overall energy input for biodiesel synthesis using purified glycerol was higher (72.7 GJ/tonne FAMEs) than for sludge (54.75 GJ/tonne FAMEs), demonstrating the benefits of sludge. Chilakamarry et al. [

11] considered it a vital fuel for the future due to its carbon-reducing properties. However, additional production has produced waste glycerol byproducts. New, safe uses for crude glycerol are needed to address the waste problem. Glycerol can be utilized in various sectors to produce chemical intermediates and other products due to its versatility. This requires innovative, safe solutions for the use of crude glycerol. Glycerol's versatility enables it to be converted into various value-added products across multiple industries, with bioconversion serving as a viable, environmentally benign alternative.

Transesterification of wasted cooking oil produced glycerol as a byproduct of methyl ester synthesis by Syahputra et al. [

12]. To compare the extracted glycerol from waste cooking oil with commercial glycerol, IR and GC-MS spectroscopy were used. Commercial and waste cooking oil glycerol have identical 1,2,3-propanetriol groups. The retention times for spent cooking oil and commercial glycerol were 9.6-10.3 and 9.6-10.13 minutes, respectively. The IR spectra of glycerol from waste cooking oil showed OH, CH, C=O, and C-O functional groups, similar to those of commercial glycerin. Rizky et al. [

13] purified palm oil-based biodiesel byproduct, glycerol, using household vinegar. Glycerol concentration peaked at 83.47% after purification. Purified glycerol has a water content of 1.83% at its lowest. Purified glycerol has an alkaline pH, with the lowest at 12.00. Refined glycerol was blackish-brown. Overall, the study successfully purified crude glycerol from biodiesel byproducts using home vinegar, producing a product with high glycerol concentration, low water content, an alkaline pH, and a blackish-brown color. Moklis et al. [

14] examined current and future trends in upgrading the biodiesel byproduct, crude glycerol, into higher-value compounds. We aim to make biodiesel production more profitable and mitigate the environmental impact of crude glycerol disposal. Crude glycerol often contains impurities that limit its industrial use, necessitating expensive processing. Not suited for food, medicine, or cosmetics due to its lesser purity (60-80%) than refined glycerol. Low heating value, excessive oxygen concentration, and poor combustion performance are further drawbacks. An excess of crude glycerol from biodiesel production could pose social and environmental issues if not properly managed. Agnesty et al. [

15] found that used cooking oil (UCO) met SNI 01-3741-2002 quality standards for smell, taste, visual color, water content, free fatty acids, acid number, and peroxide value. This violation means the UCO was toxic and unsafe for reuse or consumption. The maximum biodiesel yield from UCO was 81.33%, and the minimum was 61.7%. The FAME level was 98.18%, and the glycerol content was 0.72%. The most abundant component was methyl palmitate (47.57%), whereas the least abundant was methyl myristate (1.502%). Kumar et al. [

16] successfully demonstrated a waste-oil-burning system, yielding several interesting discoveries. Waste oil needed an ignition source to burn for 3-5 minutes, according to initial tests. Kerosene was used to ignite waste oil at 300°C. The insufficient burner area and tall stove prevented the flame from reaching the top layer; therefore, the original attempt failed. After learning from this, a more miniature stove with ample burner space was made, yielding a positive result. An iterative design process helped the team develop a waste-oil burner. Samadov et al. [

17] studied vegetable oil processing, which improves crude oil quality, appearance, stability, and safety by removing FFAs, phospholipids, waxes, colors, and other contaminants. Unfortunately, many refining processes remove tocopherols and phytosterols, which are essential for making oil healthy and stable. Armylisas et al. [

18] observed that palm-based crude glycerol (CG) and GP from biodiesel and oleochemical refineries had different colors and characteristics. However, all samples maintained a high glycerol content of up to 87.3%. The presence of these pollutants changed physical appearance, pH, viscosity, density, elemental and metal composition, and energy content. Soni et al. [

19] created groundnut shell pellets with 20 wt%, 40 wt%, and 60 wt% crude glycerol. The goal was to employ the biodiesel byproduct, crude glycerol, and to improve biomass handling and energy density. Adding glycerol to the pellets increased the volatile matter concentration from 72.45% to 85.18%. Batch pyrolysis of glycerol-containing pellets (0.5 kg) boosted bio-oil yield from 30 to 41 wt% as the glycerol content increased from 0 to 60 wt%. On a batch basis, glycerol concentration increased pyro-gas production from 28 to 32 wt%.

Glycerol production has increased due to the demand for biodiesel, according to Dhabhai et al. [

20]. In crude glycerol, free fatty acids, inorganic salts, water, and methanol are impurities. These impurities lower the economic value of glycerol, making it unsuitable for direct use. To make biodiesel profitable, this low-value crude glycerol must be refined and transformed into value-added chemicals. Pamanes et al. [

21] demonstrated good ruminal fermentation, including an adaptation phase with no significant variations between treatments. All treatments increased gas production relative to the control, which is good. The study indicated that 20 and 40 g/kg maize oil lowered the methane (CH4) to carbon dioxide (CO2) ratio by 7% and 9.5%, respectively. The maize oil treatment produced the least CH4, suggesting it could be a feeding method to reduce greenhouse gas emissions without lowering gas production. Wu et al. [

22] suggested using FAME and glycerol to enhance the economic and environmental competitiveness of biodiesel enterprises.

Make value-added epoxidized acyl glycerides. A 200°C temperature and a 1:1 FAME-to-glycerol molar ratio were found to be optimum for this reaction. Approximately 50% monoacyl, 40% diacyl, and 10% triacyl acyl glycerides were produced. The monoacylglyceride concentration strongly affected epoxide selectivity during epoxidation. A therapy that maintained monoacyl glycerides below 5% improved this phase. Borowka et al. [

23] examined the purification of biodiesel glycerin using ion-exchange resins. Biodiesel production from vegetable raw materials yields glycerin with trace amounts of sulfur, chlorine, and nitrogen. Despite low chlorine levels, glycerine from vegetable oils, UCOs, and animal fats is contaminated with sulfur and nitrogen compounds. Glycerin from UCOs is rich in nitrogen. Glycerine cannot pass through the ionite bed because its MONG (organic compounds other than glycerol) impurities are released in a separate phase. Silva et al. [

24] refined crude glycerol to greater than 98% purity by weight. Excellent purity made it ideal for etherification. Purified and commercial glycerol were employed in solvent-free batch reactor etherification processes with ethanol, isopropanol, and 3-methyl-1-butanol, using Amberlyst 15 as a catalyst. Glycerol conversion was 97% by weight with 80% monoether selectivity when ethanol was used. Up to 95% glycerol conversion with isopropanol yielded 76% monoether and 22% diether. Rahman et al. [

25] found that converting the biodiesel byproduct, crude glycerol (CG), into bioethanol could provide a sustainable energy source. Managing the growth of glycerol production while contributing to renewable fuels is challenging. Crude glycerol, abundant in biodiesel production, can be used to synthesize bioethanol. This turns trash into a resource. Many crucial processes must be optimized to convert glycerol to bioethanol. Increase fermentation efficiency to maximize glycerol bioethanol yield. Genetic engineering advances are needed to generate more efficient and prolific converting microorganisms. To ensure the purity of bioethanol, effective filtration is necessary.

Perez et al. [

26] investigated biomass-derived carbon catalysts for the esterification of crude glycerol and acetic acid. The goal was monoacetyl, diacetyl, and triacetyl glycerol. Peanut shells (PC) were activated with KOH (APC) and functionalized with H2SO4 to make PC-F and APC-F catalysts. Functionalized catalysts were tested in crude glycerol. This crude glycerol was synthesized from biodiesel and had an acidic pH, containing water, methanol, Na2SO4, and non-glycerol organic debris. APC-F outperformed PC-F in catalyst testing. The perfect combination of surface acidity and textural qualities increased performance. Sidhu et al. [

27] examined water and glycerin emulsification techniques for biodiesel combustion emissions, focusing on their performance and valorization potential. Both water and glycerin emulsion fuels significantly reduced smoke emissions. Compared to pure biodiesel, emulsions with 10% glycerin or water reduced smoke emissions by almost 50%. The study found that both emulsification methods significantly lowered biodiesel NOx emissions. More than 15% less NOx was released with 10% glycerin and water emulsions. This addresses a common issue: biodiesel use increases NOx. Bansod et al. [

28] conducted a cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to assess the environmental impacts of three crude glycerol purification methods and identify the drivers and mitigation measures. The LCA compared three methods for purifying crude glycerol: PMP, VDP, and IEP. A 1000-kg pure glycerol functional unit was assessed. The processes exhibited carbon footprints of 3,466.82 kg CO2 eq. FU−1, 1745.72 kg, and 2239.71 kg, respectively. Waste from crude glycerol impurities significantly increased the environmental impact of all three processes, the study found. The carbon footprint and other environmental implications were also affected by the PMP and IEP physicochemical treatment raw materials. Roschat et al. [

29] demonstrated that activated carbon derived from Krabok (Irvingia malayana) seed shells enhances biodiesel production by utilizing crude glycerol. Dry chemical activation with NaOH and an innovative biomass incinerator created activated carbon (KC/AC-two-step) from Krabok seed shells. The KC/AC two-step showed strong physicochemical adsorption, as evidenced by a high surface area of 758.72 m²/g and an iodine number of 611.10 mg. These values meet the activated carbon industrial product standard issued by Thailand's Ministry of Industry, TIS 900-2004. Methylene blue adsorption by activated carbon was 99.35% superior. KC/AC two-step activated carbon improved the crude glycerol purity to 73.61%. Commercial activated carbon (C/AC) was 81.19% pure, whereas Krabok-derived activated carbon was cleaner. Glycerol's Zn, Cu, Fe, Pb, Cd, and Na levels dropped significantly after purification. Agrawal et al. [

30] examined the sustainability of solketal synthesis from glycerol amid increased biodiesel output and alternative fuel demand. The biodiesel industry produces a significant amount of glycerol that pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies do not use. The project explores environmentally friendly methods for utilizing surplus glycerol and creating valuable products. Solketal, a gasoline additive, is effectively made from glycerol. Its production from glycerol addresses traditional fuel problems and promotes the use of alternative fuels. Batch and continuous solketal synthesis are employed, with the latter showing the most promise. Various homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts are used to increase solketal yield in reactors for glycerol and dimethyl ketone reactions. Ruzibayev et al. [

31] improved the purification of crude glycerol to produce high-quality glycerol without distillation. This was done with cations. A 70:30 blend of activated carbon and clay yielded the best results across both glycerol and ash levels. Pilicita et al. [

32] evaluated spent cooking oil as a sustainable biodiesel alternative, emphasizing its potential to reduce fossil fuel usage and mitigate environmental challenges while exploring methods to enhance its properties and improve engine performance. This article discusses biodiesel manufacturing using residual cooking oil, which can reduce fossil fuel consumption and environmental impact. Used cooking oil is abundant and inexpensive, making it a viable solution for circular economy waste management. Biodiesel generated from waste cooking oil through transesterification exhibits biodegradability and reduced greenhouse gas emissions; however, it also has high viscosity and nitrogen oxide emissions. Haymoba et al. [

33] created vegetable oil blends with a balanced fatty acid profile, targeting a PUFA-to-PUFA ratio of 5:1 to 10:1. The researchers examined various vegetable oil quality indices. They examined PUFA fractions of these oils. The oil combination was formulated using mathematical modeling. The oils reviewed were compatible with respect to organoleptic parameters (color, clarity, taste, and smell), suggesting they may be mixed.

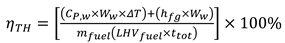

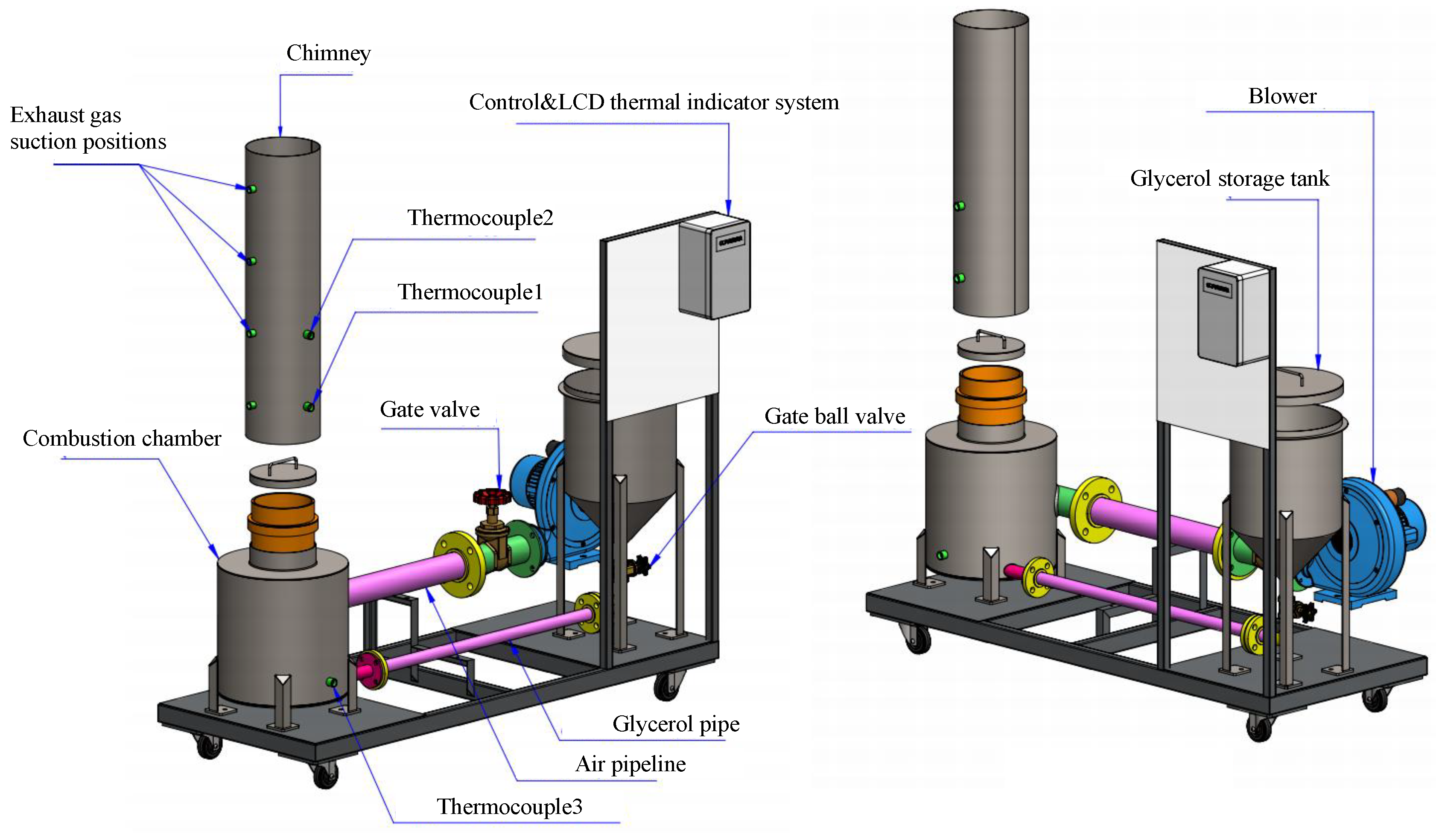

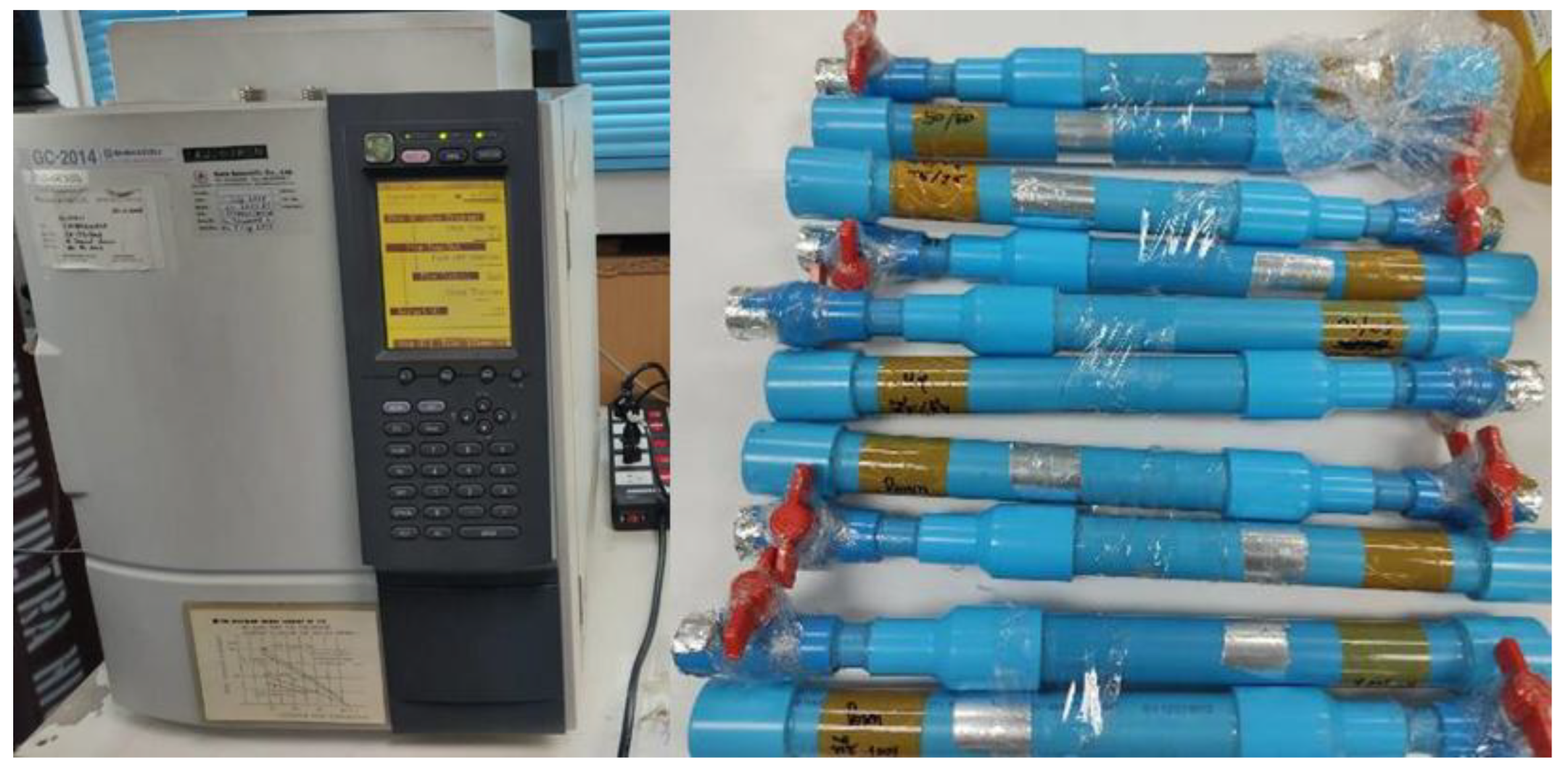

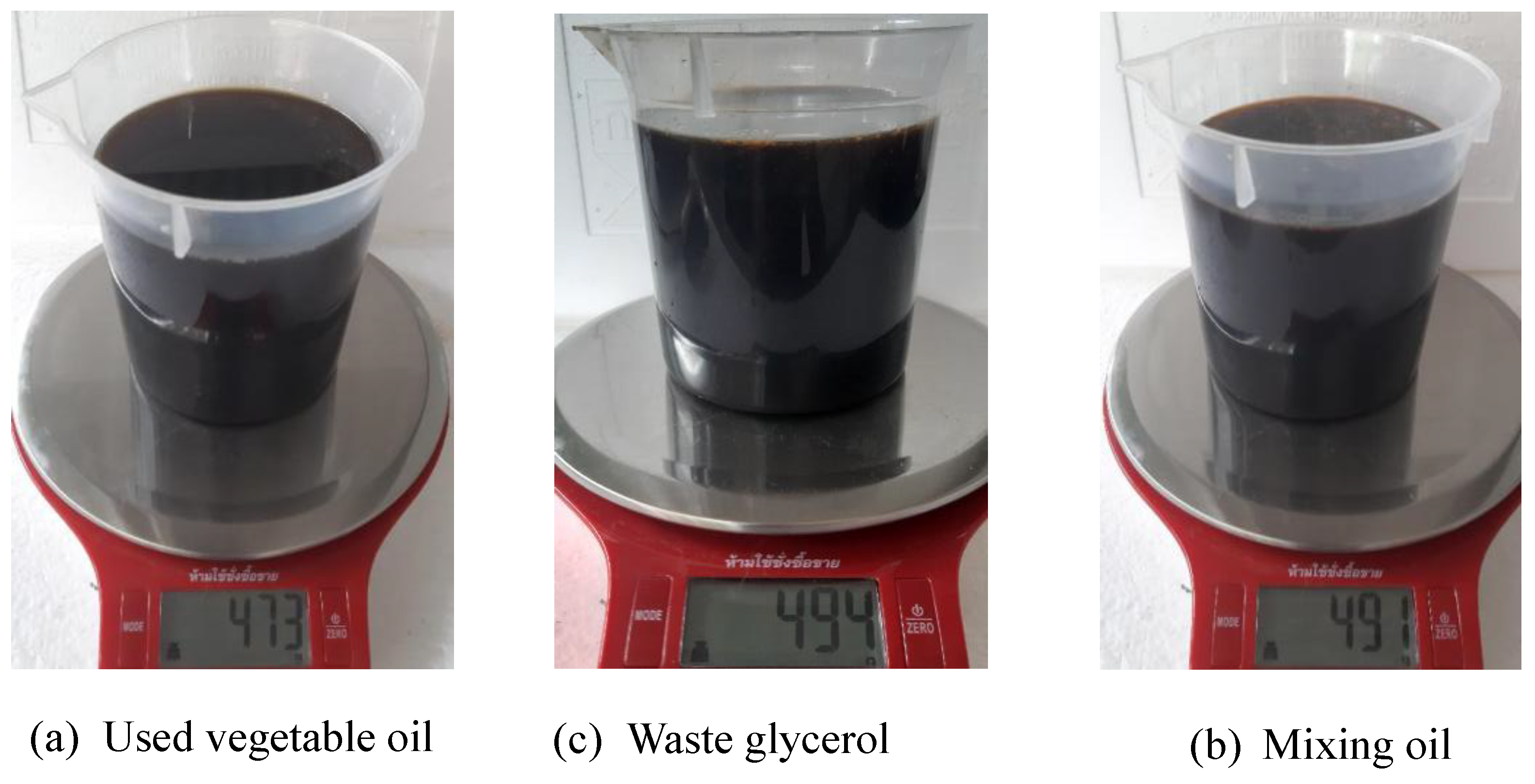

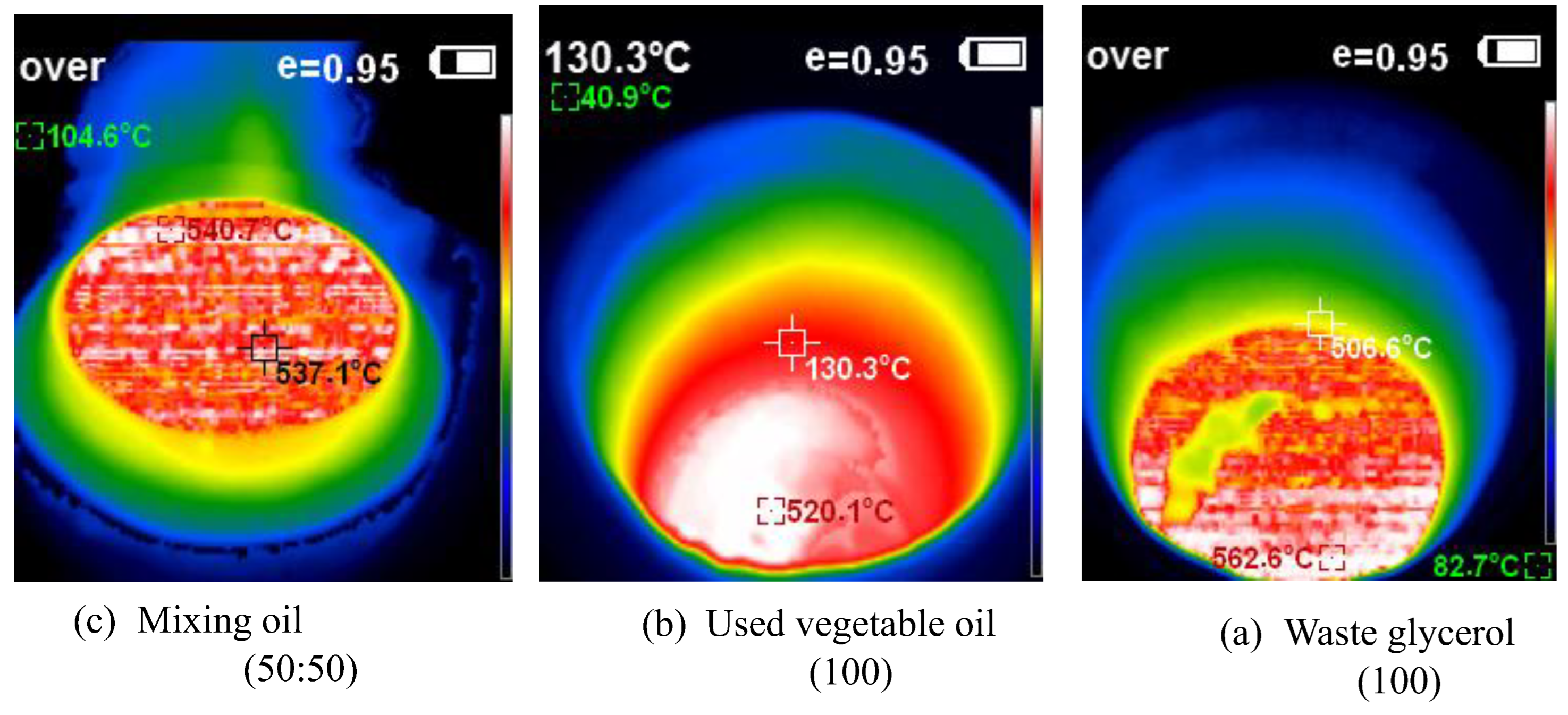

This study developed and tested a mixed-fuel burner and furnace system that steams mushroom substrate cubes using crude glycerol and vegetable oil to reduce fuel costs, waste, and energy efficiency. Preparing five fuel mixtures (100% glycerol, 100% used vegetable oil, and 50/50, 25/75, 10/90 blends), testing combustion and thermal efficiency using DIN EN 203-1 standards, and measuring temperature profiles, exhaust-gas composition, steam generation, and boiler performance with analytical modeling of furnace pressure, temperature, and combustion-gas distribution were the experimental methods.

3. Analytical Analysis

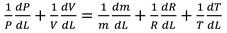

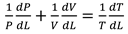

To get the thermodynamic equations for the fuel-air mixture, we utilize the governing equations of a miniature furnace. A few of the furnace's fundamental physical features include the fuel-air combination, the combustion process, and the combustion gases, which mix with the air to determine when the Fuel and air have been burnt out. Fuel vapor is produced when glycerol, combined with vegetable oil boils. Afterwards, it makes its way into the furnace to be fully mixed with air. Part one of an open system, according to the first rule of thermodynamics, is the mixing zone, which consists of 1) boiling steam of glycerol and used vegetable oil combined with air, the Premixer, and 2) the second part, the equation zone.

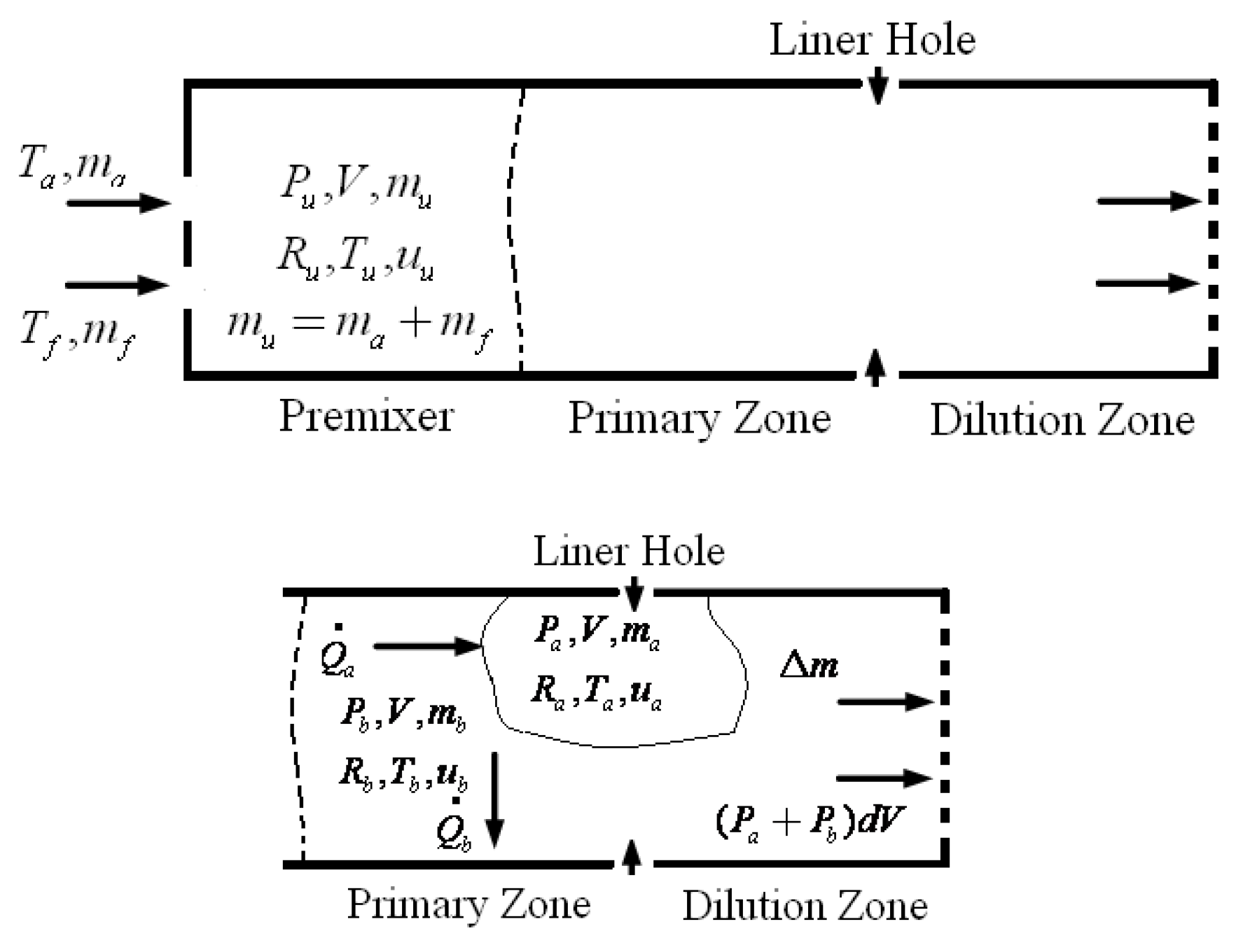

Figure 7 illustrates the distinction between the combustion gas and air mixing zones, namely the Primary Zone, and the Dilution Zone, which is the area within the liner hole where the gas is diluted due to mixing with air.

All gases in the combustion chamber are ideal gases.

Where P represents the internal pressure of the combustion chamber. V is the volume of the combustion chamber.

This is the derivative equation of the concept gas equation with respect to distance.

At each stage, when Fuel, air, and combustion are combined, the equation may be expressed as:

Base on

Figure 7, for the premix zone, the variables m

a, m

f, m

u, V, r

u, T

u, and U

u represent the following: air mass, fuel mass (boiling vapor of glycerol and utilized vegetable oil), pressure, volume of the furnace, gas constant, and temperature.

Figure 7 shows that in the primary zone, also known as the combustion zone, the mass of the air and Fuel that is burnt is equal to mu, P

b is the average pressure of the air and Fuel inside the combustion chamber at adiabatic temperatures, V is the volume of the furnace or combustion chamber, R

b is the gas constant, T

b is the system's temperature when burned (the adiabatic temperature), and U

u is the system's internal energy.

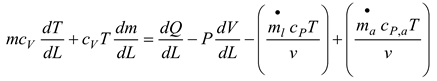

The energy balance in the system is obtained as follows;

Where m is the system's mass.

is a temporary decrease in mass.

is the volume of air that, through the liner hole, goes into the diluting phase. Gas velocity, denoted as v, and pressure, P, are two variables. In

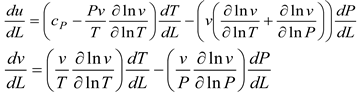

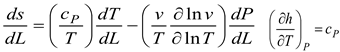

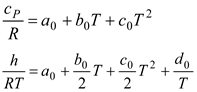

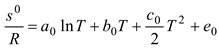

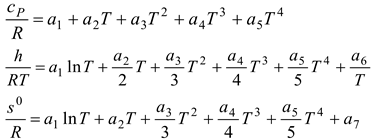

Table 2, we can see that the thermodynamic parameters that vary with distance (L(x)) are a function of both temperature and pressure, as given in Eq. 4 (Heywood, 1986; Gordon, 1975).

shows the thermodynamic parameters of the main zone (the combustion zone) as functions of temperature and pressure (T, P), which vary with distance (L(x)).

A temperature derivative equation, equalized per unit distance, may be derived from the original equation under the assumption of constant volume and average pressure. The following is an example of both burnt and unburned:

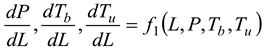

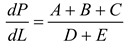

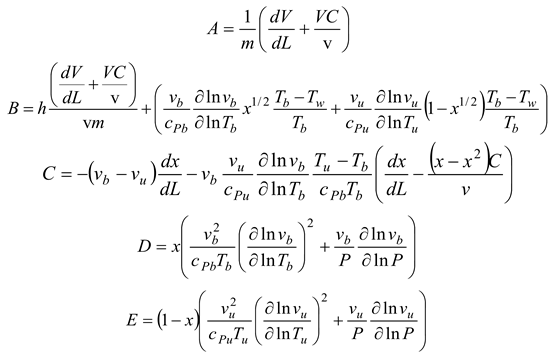

- Pressure per distance

where

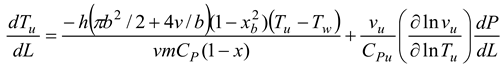

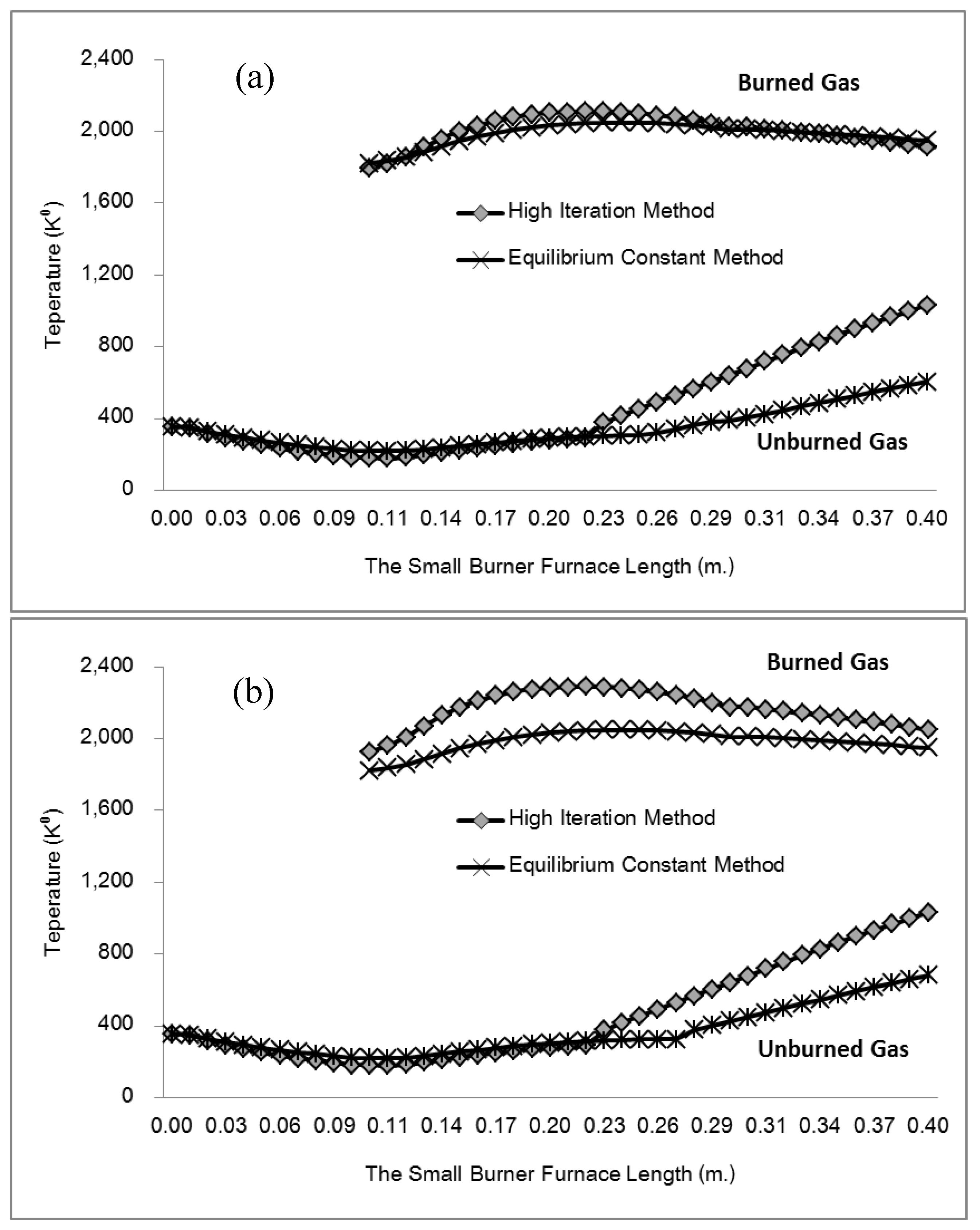

- Burning and unburned gas temperature

Where Tu is the unburned gas temperature (K), Tb is the combustion gas temperature (K), Tw is the wall temperature of the furnace, C is the initial gases blow-by is the constant obtained by repeating in the convergent process. x is the mixture of air and gas obtained from the combustion. The following can be done to simulate the burning of low-calorific fuels in miniature furnaces and flames:

- First, we will look at the enhanced procedure at the zone where the Fuel and air combine. Two distinct zones: the combustion zone and the dilution zone. In every zone, the combustion process is exhaustive.

- Combustion equation of mixed Fuel ( ), under the fuel-air ratio ε and the equivalent of air, one mole can be written as an equation.

Where is the 1st Fuel (Glycerol Vapor) and is the 2nd Fuel (Vegetable used vapor oil) [Metzger, 2007],

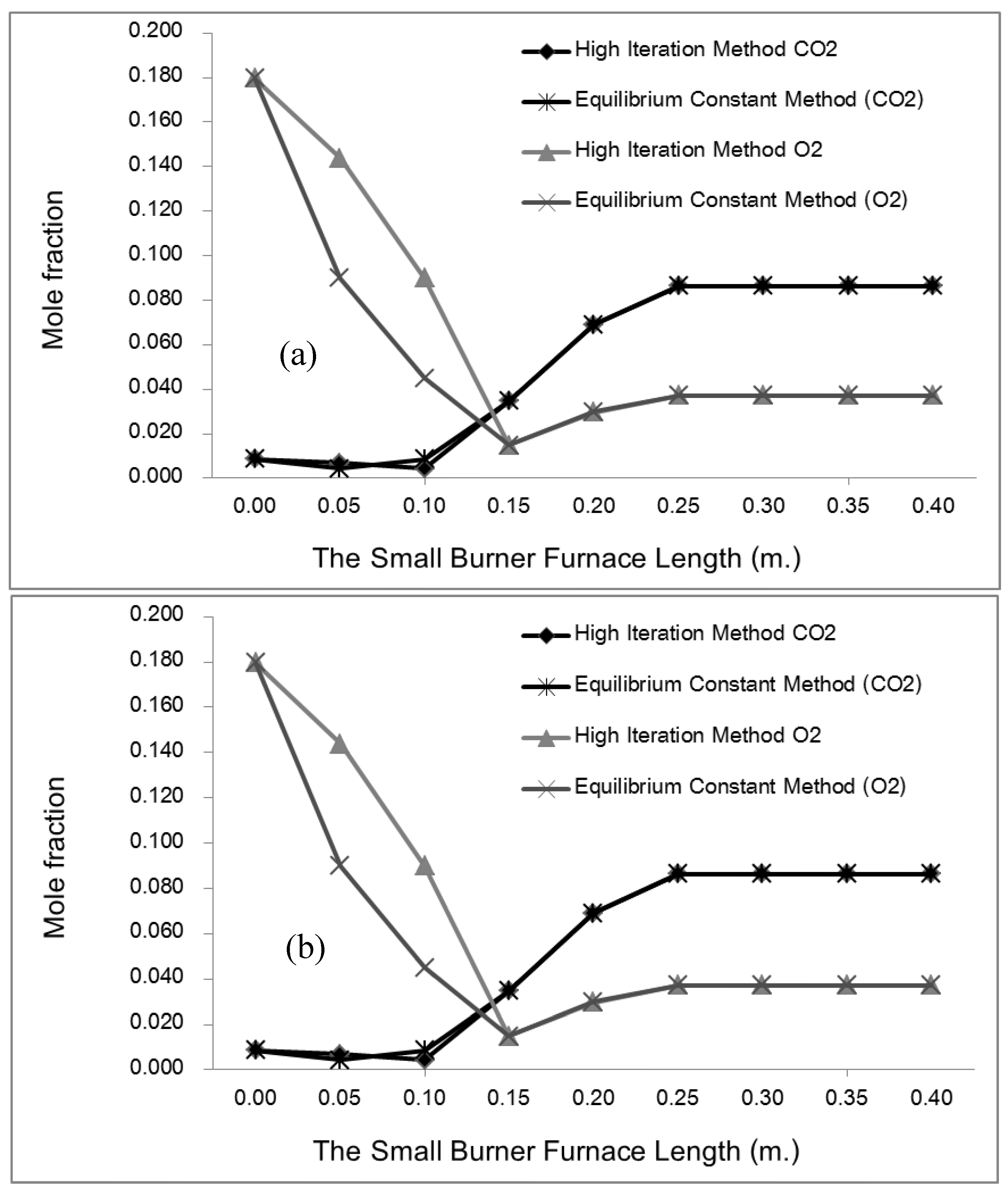

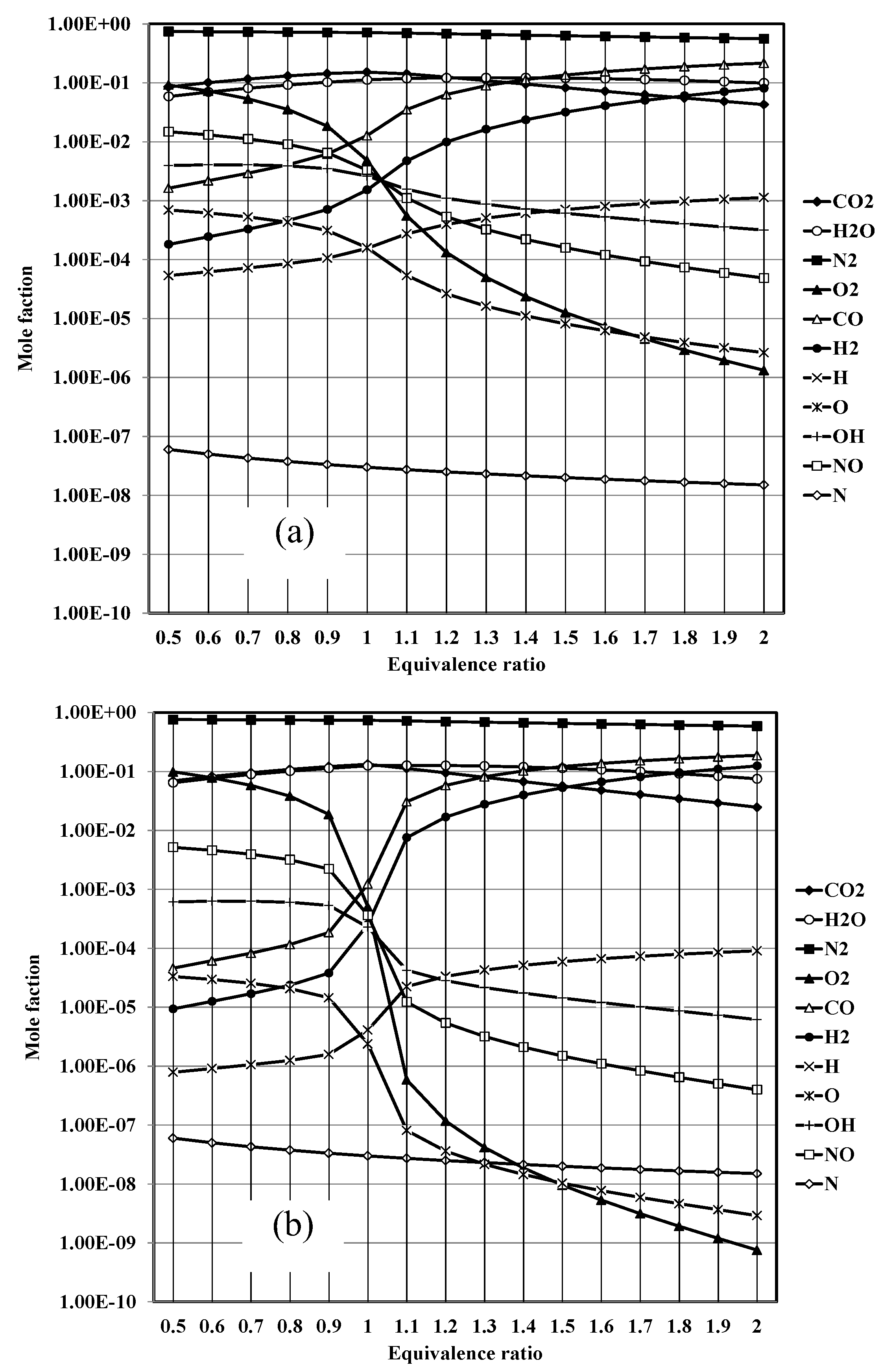

Where ν is the mole ratio of the production gases (11 types). At the chemical equilibrium, there are three zones in the considering process. In the 1st zone, fuel-air is mixing already at temperatures below 500 K, in which "C" "O" _2 "," "H" _2 O,N_2 in the exhaust gas. For the combustion zone, there are 11 different gases in the exhaust, including CO2, H2O, N2, O2, CO, H2, H, O, OH, NO, N, at adiabatic flame temperature and then the dilution zone with N2, O2 added at temperature below 1000 K. Therefore, by considering the chemical equilibrium of each zone, there are four sub-equations that are identical to each of them as follows:

In cases where y is the percentage of moles and N is the total number of moles of the product. Hence, the following is the percentage of total moles of combustion products:

Rearrangements in the linear equation form (excluding term) as follows:

Where

The procedure requires consideration of seven unknowns, the value of which exceeds that of the equations, as stated before. Hence, according to the equilibrium constant connection at the same mole ratio, pressure, volume, and temperature under the same conditions, the gases formed from combustion are considered to be an ideal gas and undergo the following breakdown [

Table 3]:

Hence, the following is how the issue is solved using the Newton approach in terms of the Taylor Series distribution:

Equilibrium may be achieved by setting Matrix Algebra, where the initial value serves as the default for solving subsequent equations until the entire error condition is met. The process is as follows:

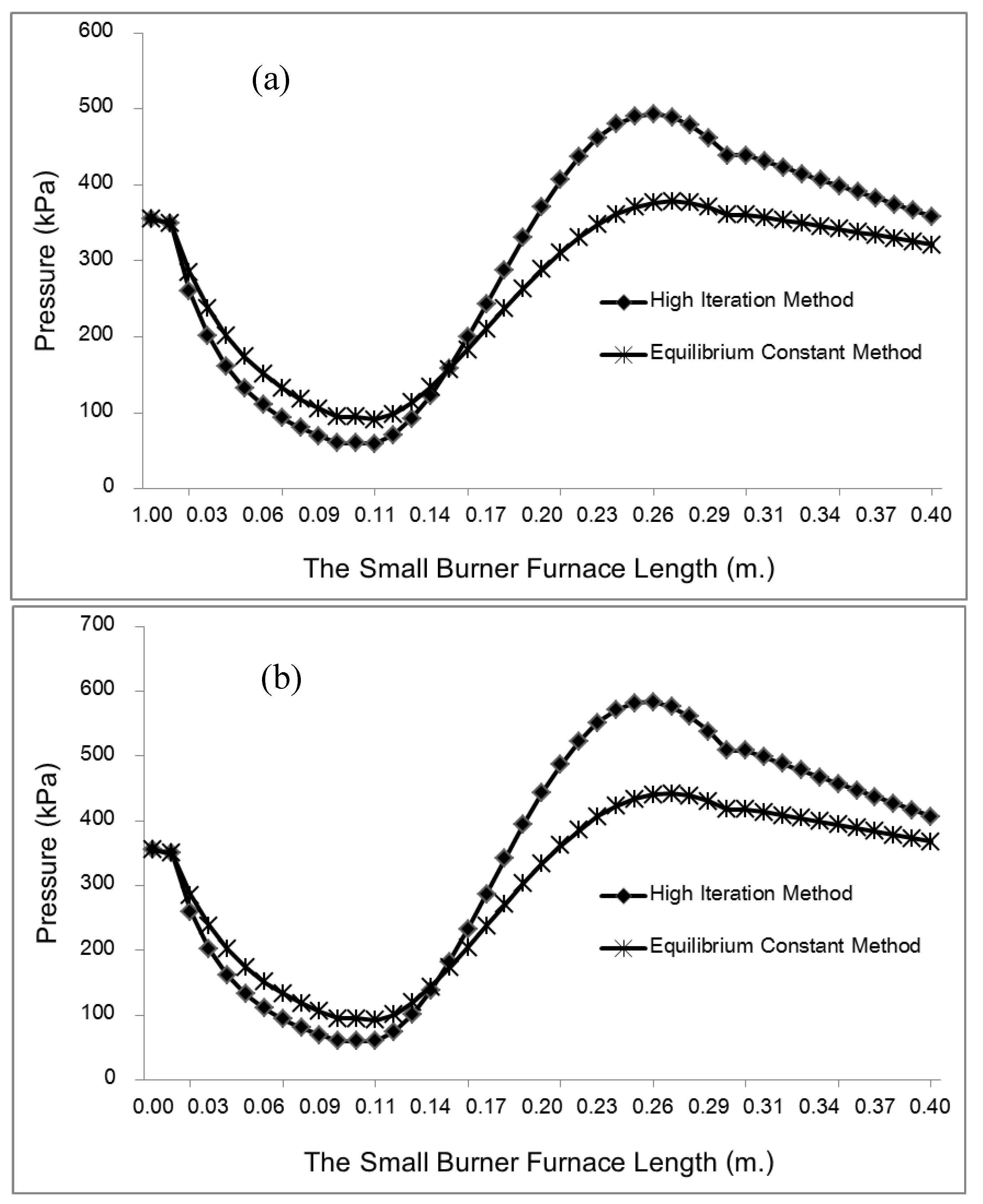

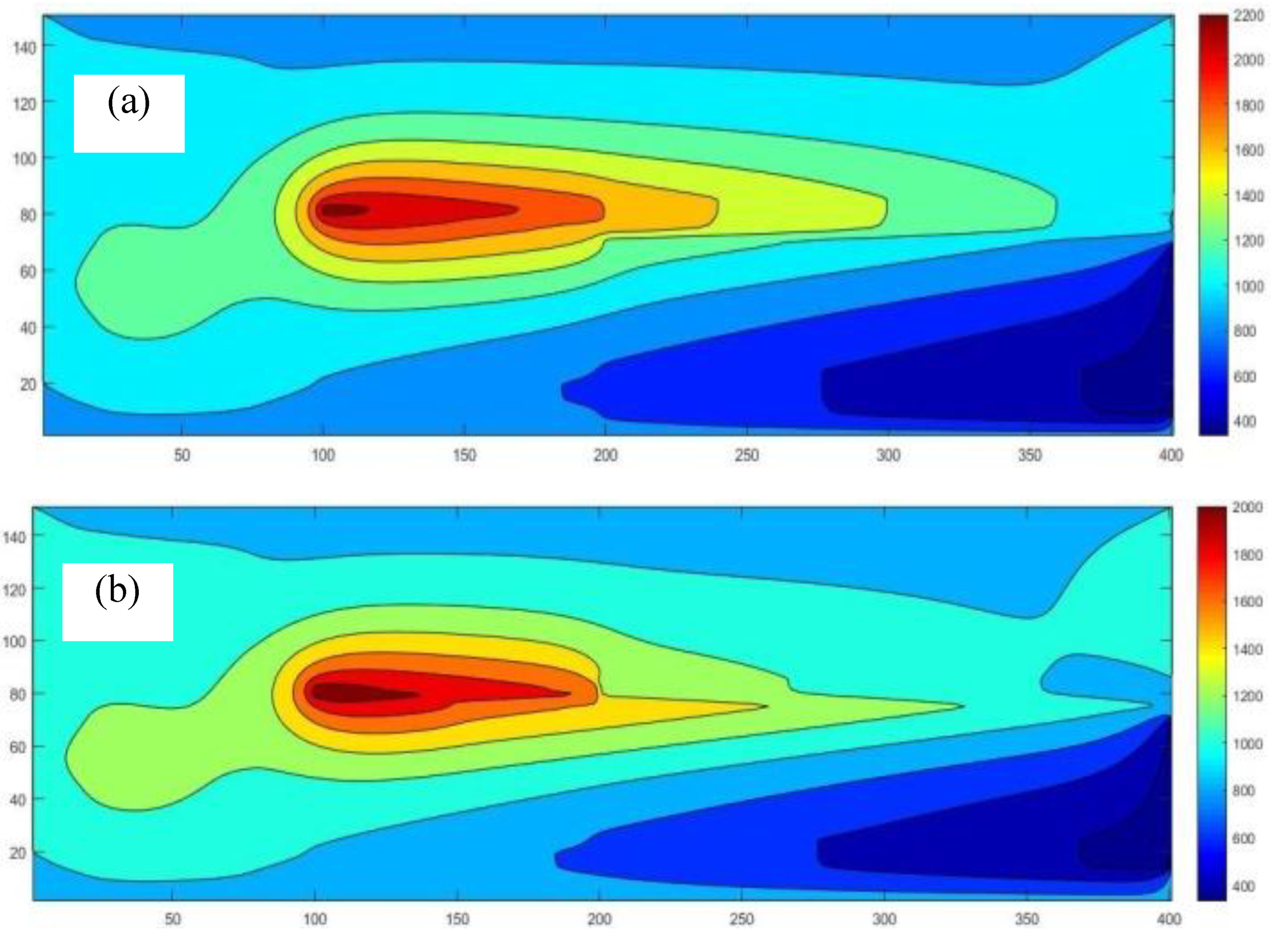

The mole proportions matrix, denoted as [Δy], is assumed to be less than or equal to zero. The constants matrix, denoted as [A], is obtained from the molar proportional derivative according to Taylor's derivative equations. The main equation matrix, denoted as [f], is solved using MATLAB. You can figure out the changes in pressure, temperature, and the velocity of exhaust gas flow from