Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

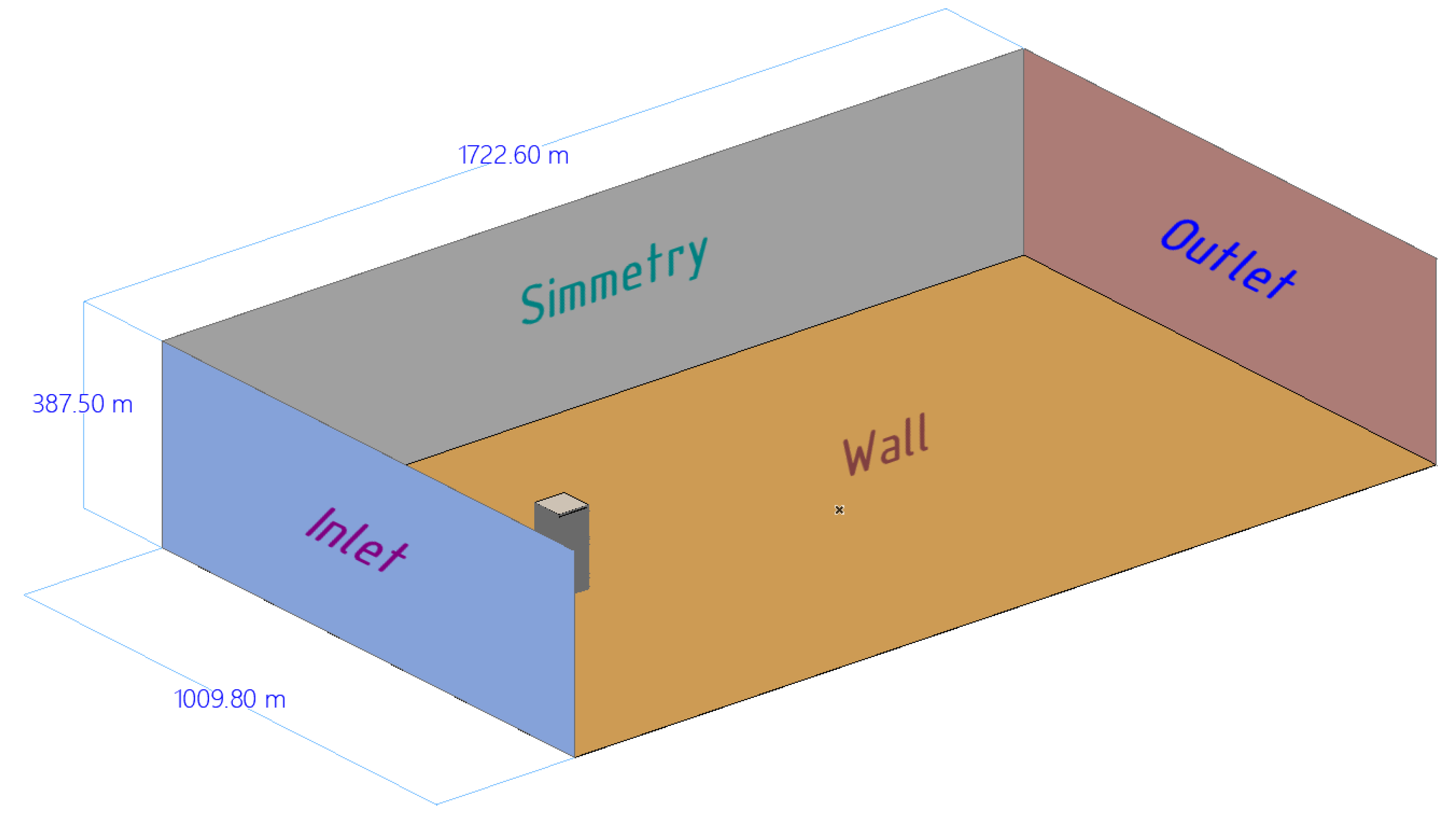

2. Materials and Methods

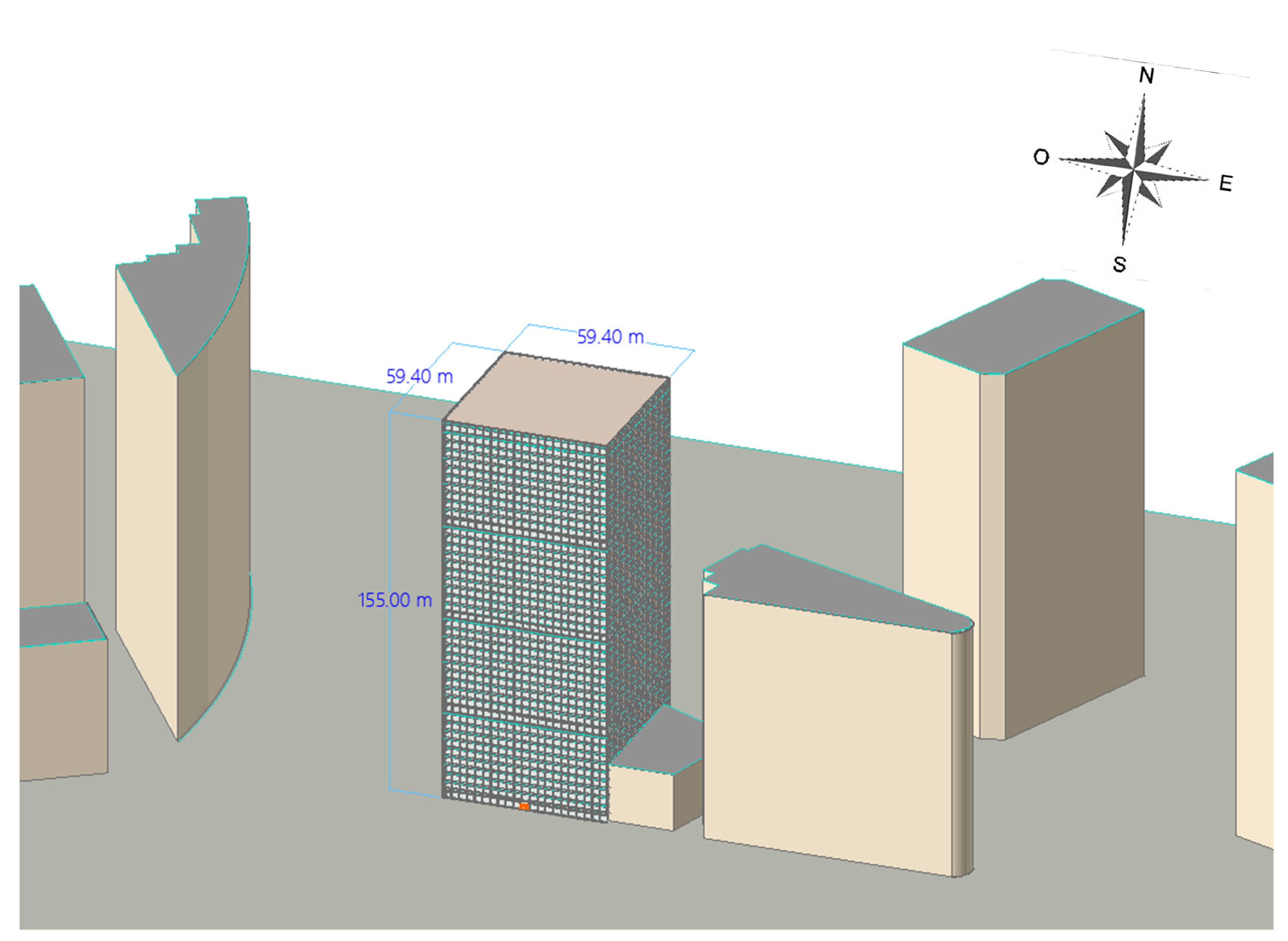

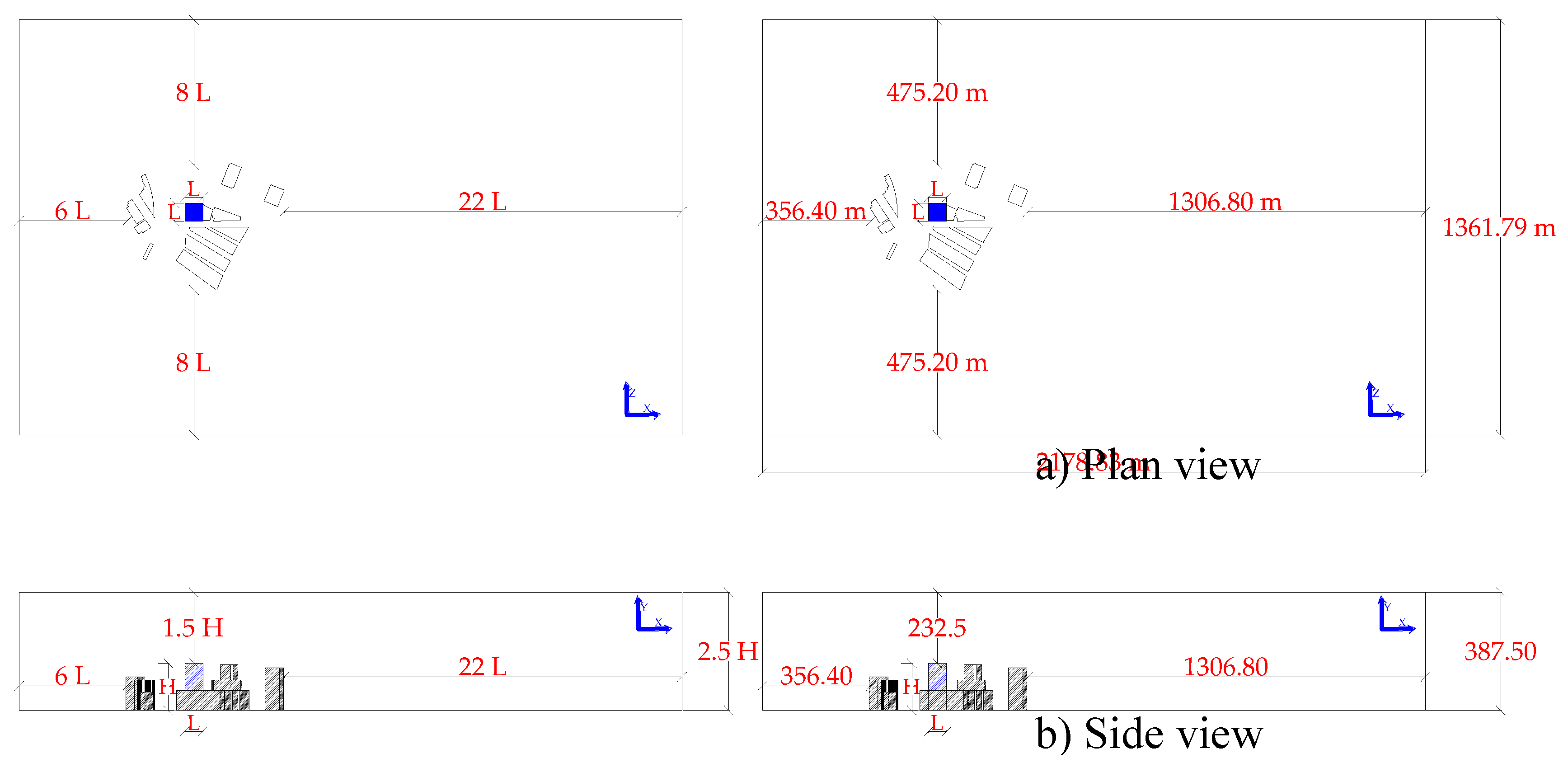

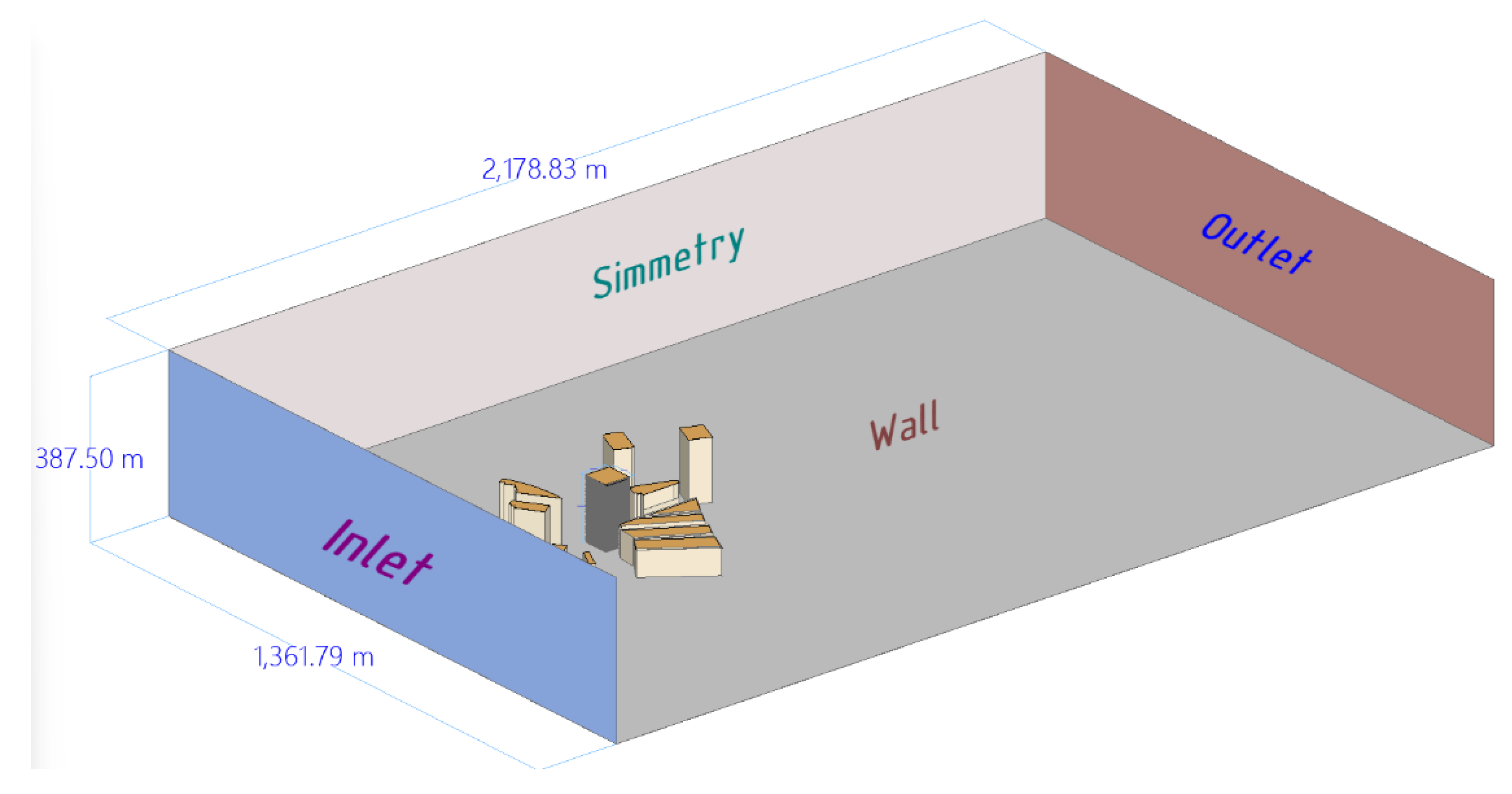

2.1. Scenario 1

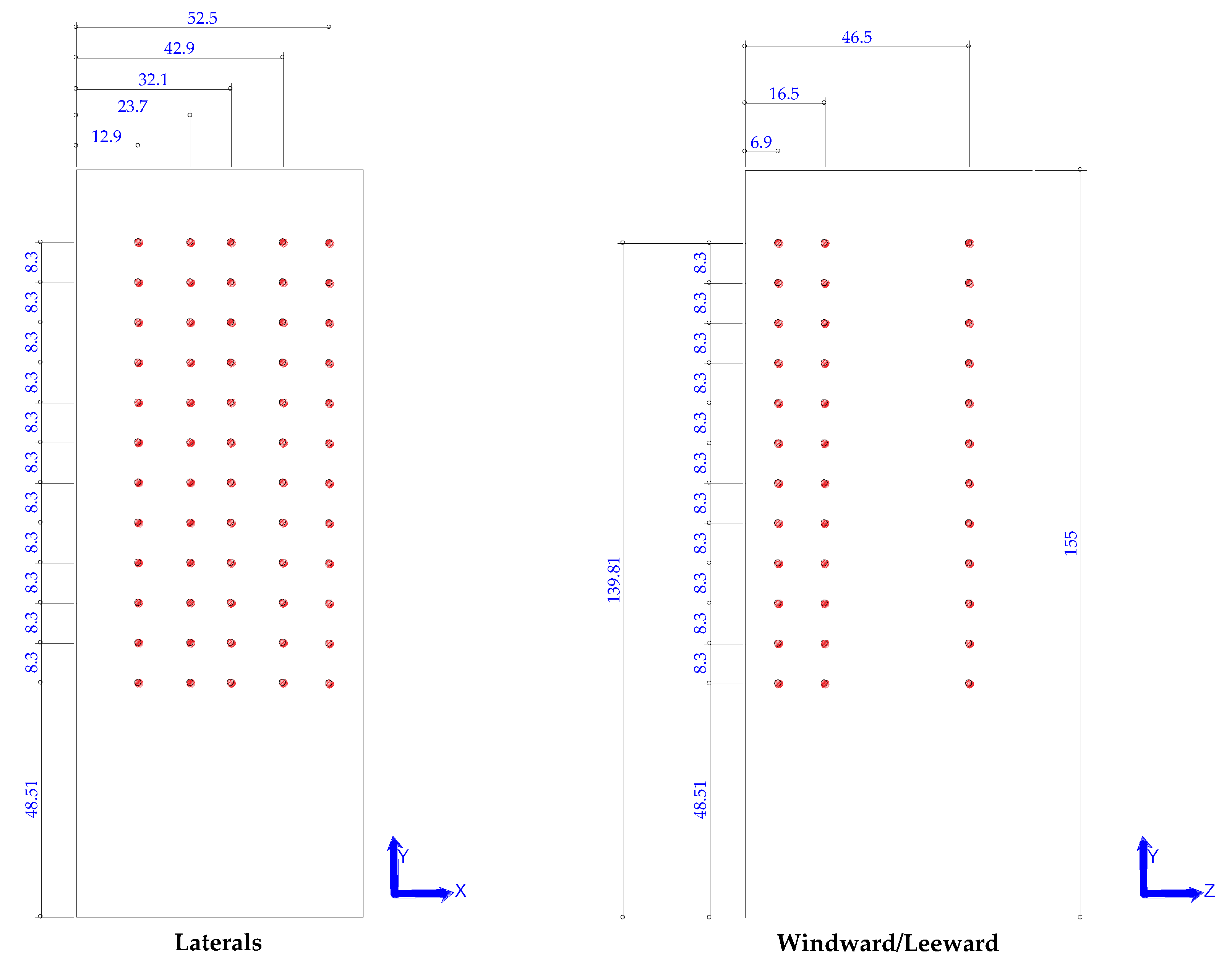

2.1.1. Pre-Process

2.1.2. Solution

2.2 Scenario 2

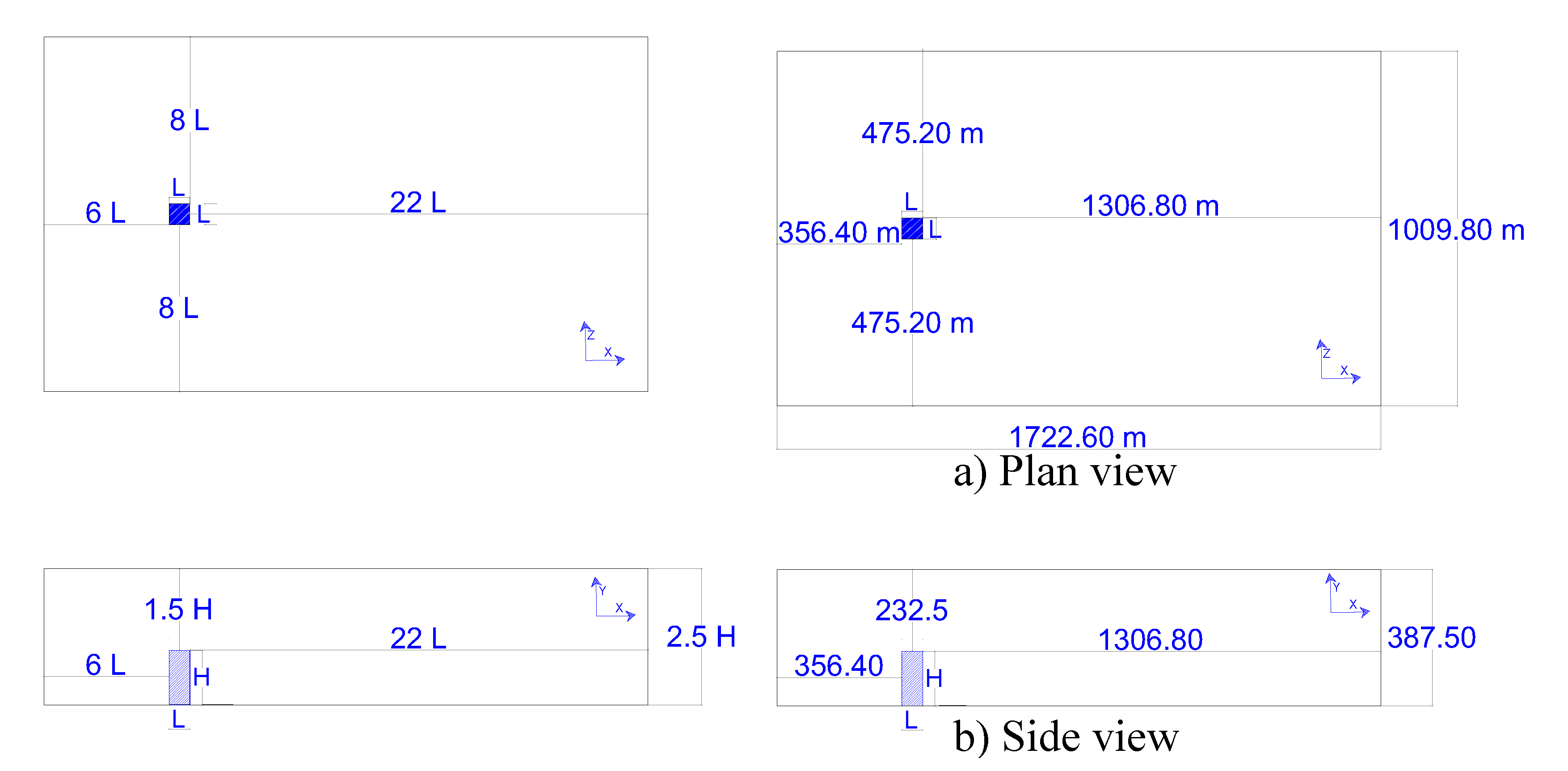

2.2.1. Pre-Process, Scenario 2

2.2.2. Solution, Scenario 2

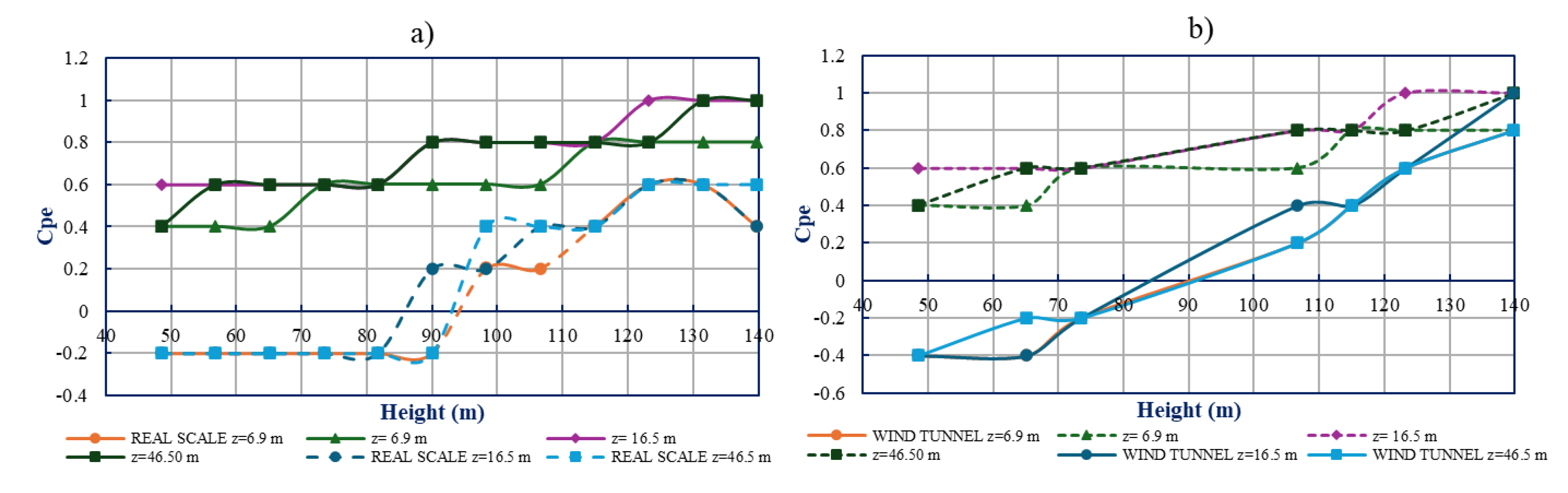

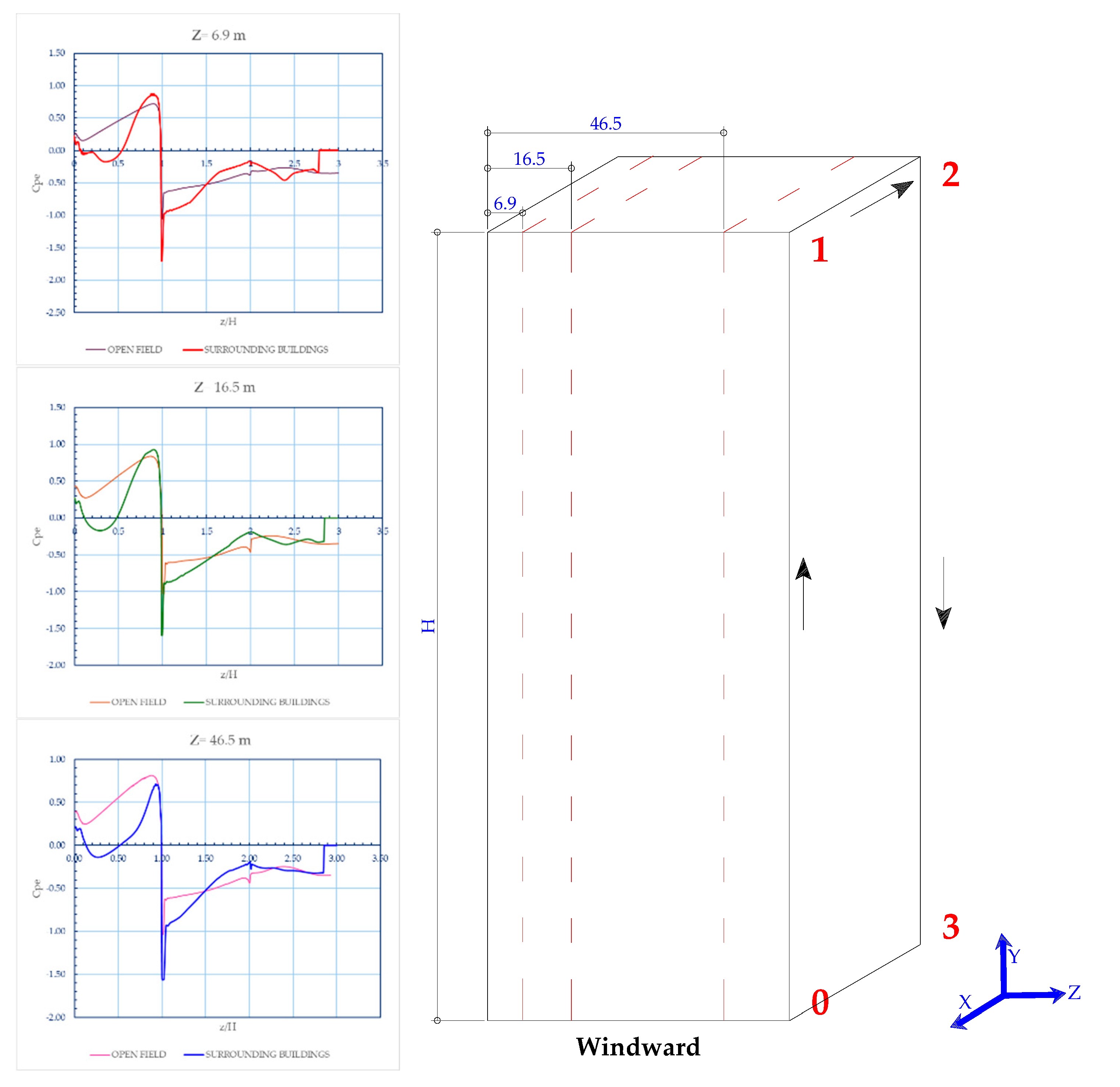

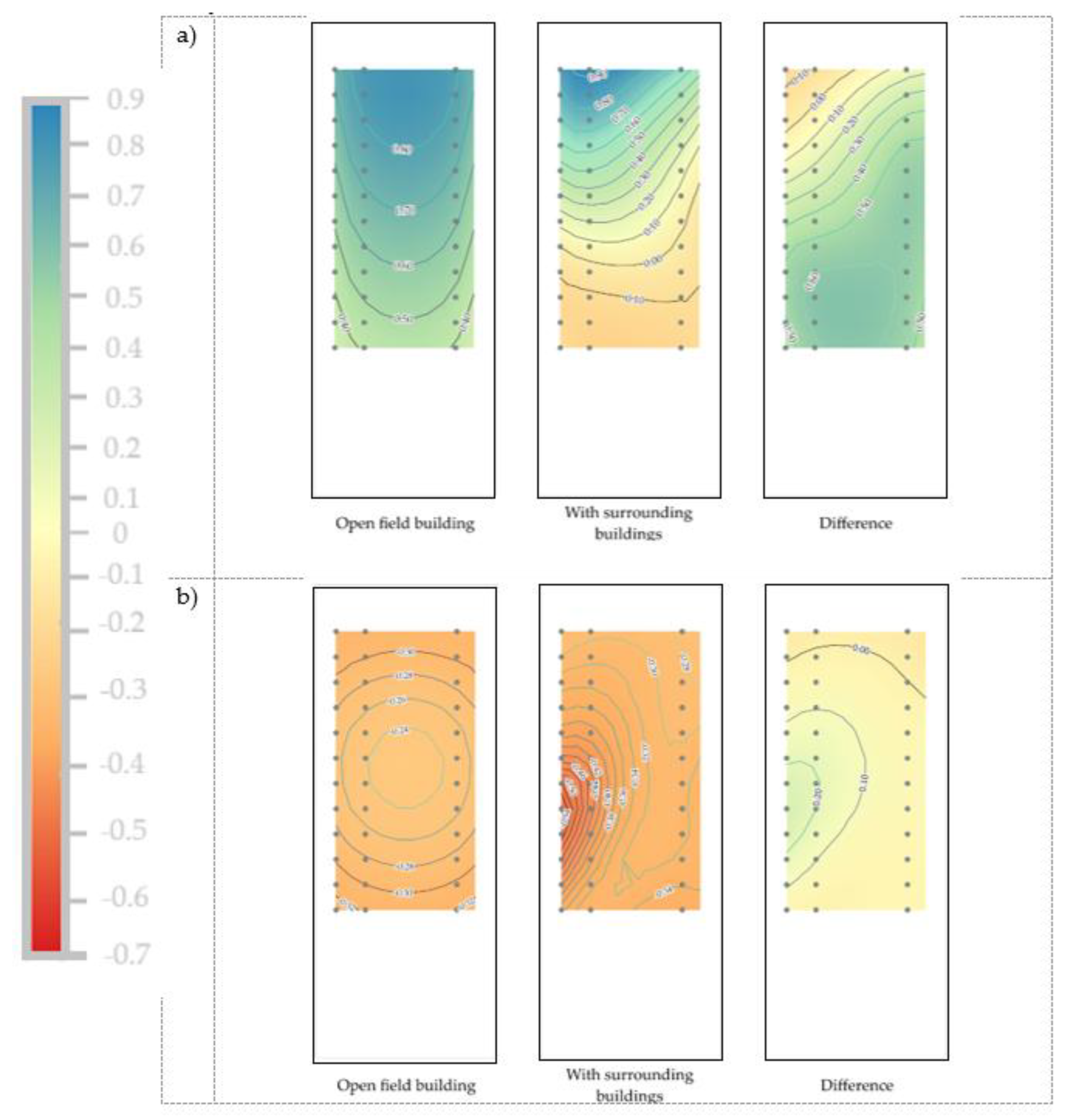

3. Results

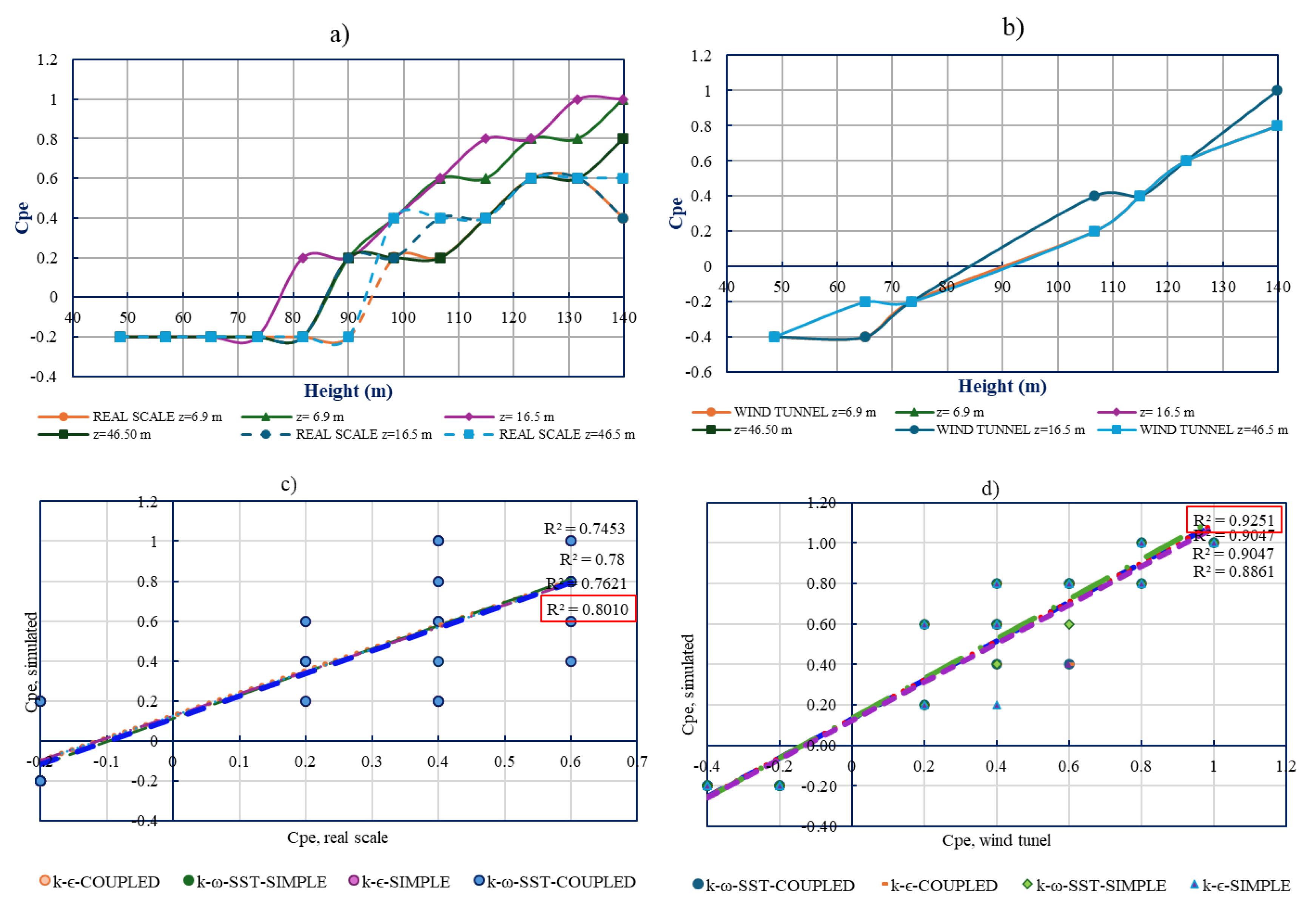

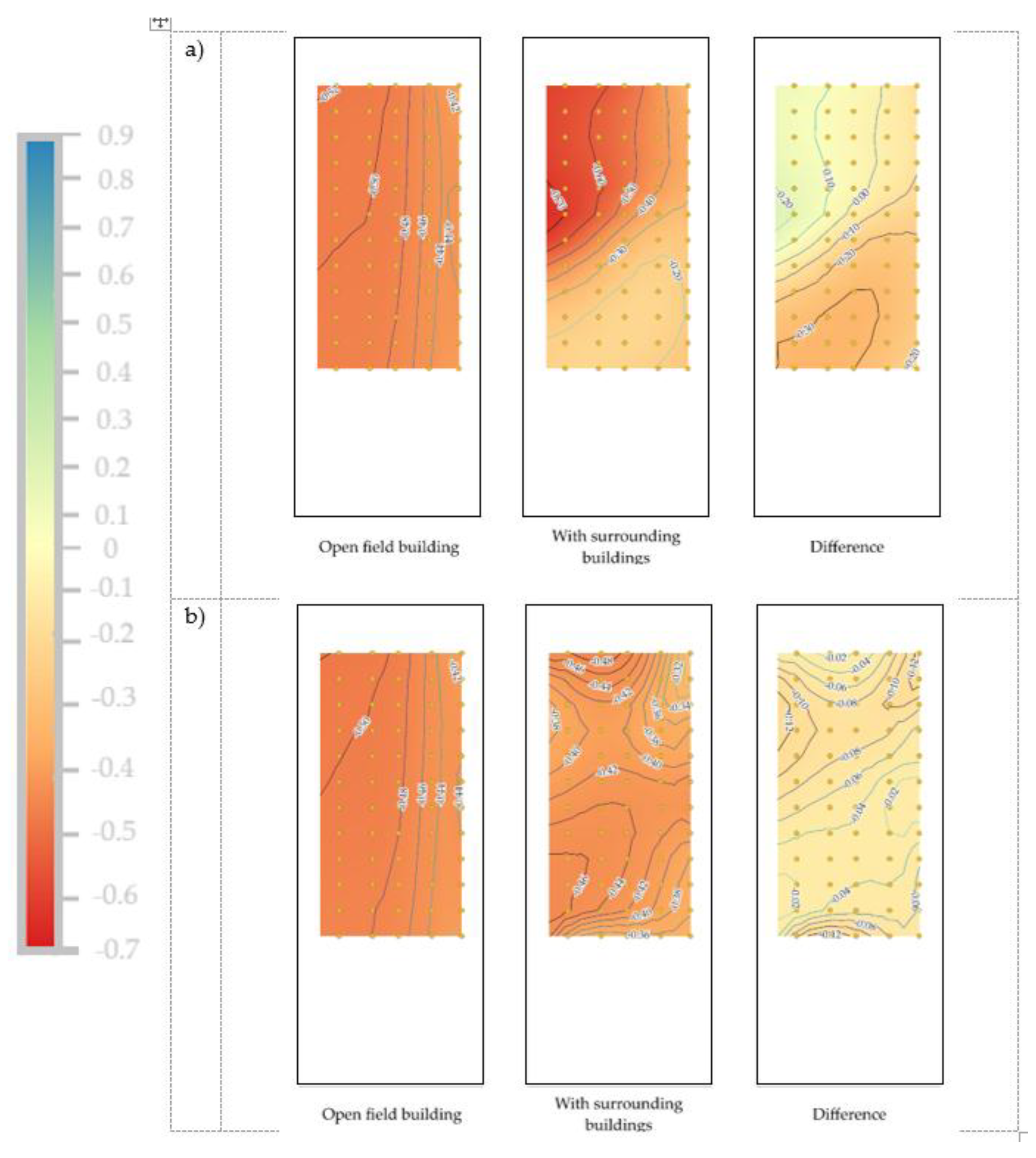

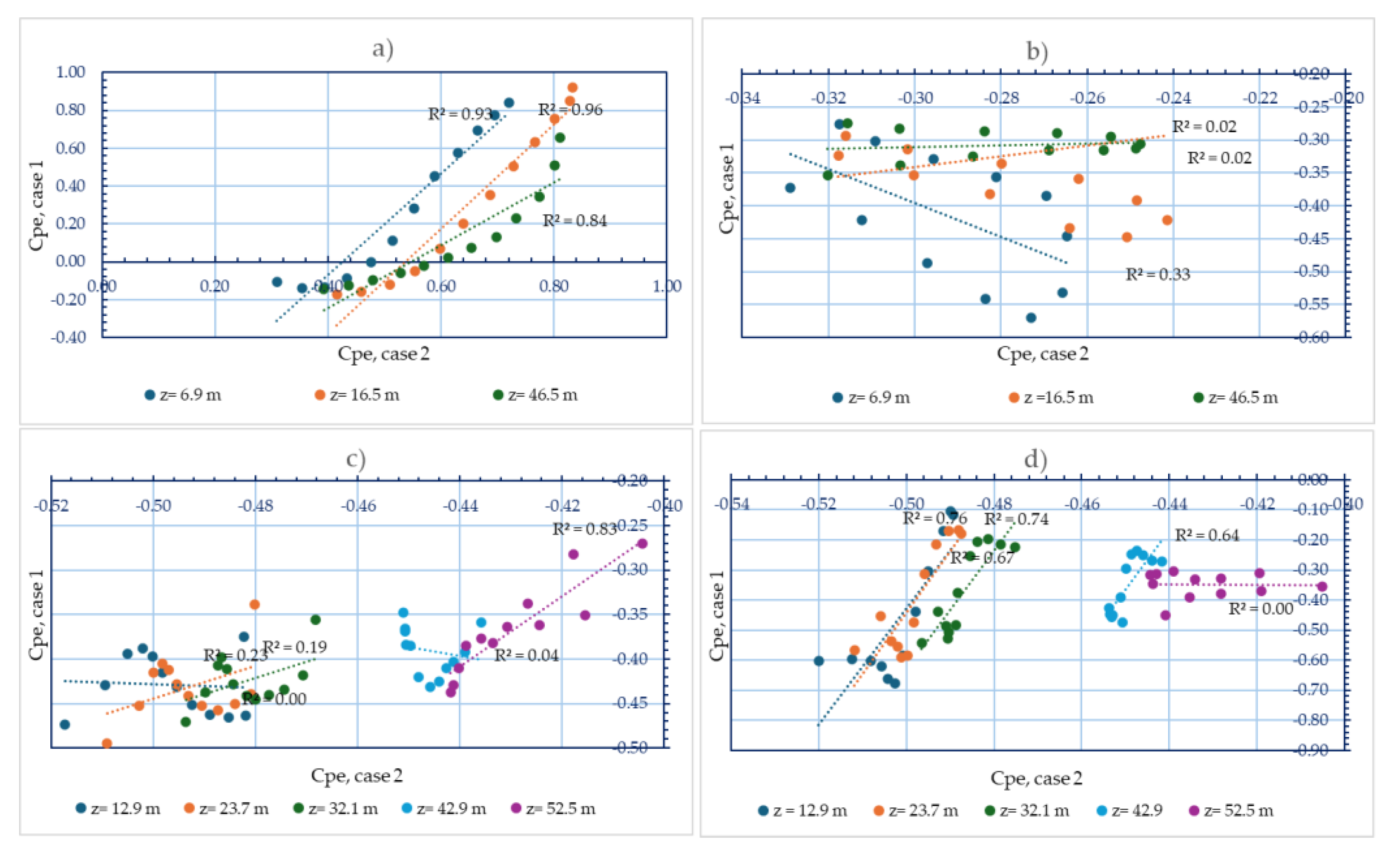

3.1. Results, Scenario 1

3.2. Results, Scenario 2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Meli Piralla, Diseño estructural, 2a. Limusa, 2001.

- Ruiz y Blanco Díaz, Mecánica de Estructuras. CIMNE, 2014.

- E. E. Koks y T. Haer., «A high-resolution wind damage model for Europe», Scientific Reports, vol. 10, n.o 1, p. 6866, abr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ouyang y S. M. J. Spence, «Performance-based wind-induced structural and envelope damage assessment of engineered buildings through nonlinear dynamic analysis», Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, vol. 208, p. 104452, ene. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tomás y M. Morales, «Revisión y estudio comparativo de la acción del viento sobre las estructuras empleando Eurocódigo y Código Técnico de la Edificación», Inf. constr., vol. 64, n.o 527, pp. 381-390, sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, R. Li, L. Feng, Y. Wu, y N. Gao, «Boundary layer wind tunnel tests of outdoor airflow field around urban buildings: A review of methods and status», Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 167, 2022. [En línea]. [CrossRef]

- M. Iancovici y G. B. Nica, «Time-Domain Structural Damage and Loss Estimates for Wind Loads: Road to Resilience-Targeted and Smart Buildings Design», Buildings, vol. 13, n.o 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Coca-Obdulio, «DAÑOS DEL VIENTO EN ZONAS URBANAS», Arquitectura y Urbanismo, vol. 29, n.o 0258-591X, pp. 64-67, 2008.

- C. Bustamante, M. Jans, y E. Higueras, «El comportamiento del viento en la morfología urbana y su incidencia en el uso estancial del espacio público, Punta Arenas, Chile», AUS, n.o 15, pp. 28-33, 2014.

- C. Lin, R. Ooka, Y. Takakuwa, y H. Kikumoto, «Wind tunnel study of Parapet effects on rooftop wind environment with implications for safe urban-air-mobility operations», Building and Environment, vol. 284, p. 113509, oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y., Yoshida, A., Yamane, Y., y Akashi Mochida, «Impact of a single high-rise building on the wind pressure acting on the surrounding low-rise buildings», Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, vol. 250, n.o 105742, 2024. [En línea]. [CrossRef]

- Xamán, Dinámica De Fluidos Computacional Para Ingenieros. Palibrio, 2016.

- F. M. White, Mecánica de fluidos. Madrid: Mcgraw-Hill, 2010.

- H. K. Versteeg y W. Malalasekera, An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, Second Edition. Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

- Baghaei Daemei, E. M. Khotbehsara, E. M. Nobarani, y P. Bahrami, «Study on wind aerodynamic and flow characteristics of triangular-shaped tall buildings and CFD simulation in order to assess drag coefficient», Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 10, n.o 3, pp. 541-548, sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Khalil y I. Lakkis, Computational Fluid Dynamics: An Introduction to Modeling and Applications, 1st Edition. McGrawHill, 2023. [En línea]. https://books.google.com.mx/books/about/Computational_Fluid_Dynamics_An_Introduc.html?id=eMCqEAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y.

- K. Wijesooriya, D. Mohotti, C.-K. Lee, y P. Mendis, «A technical review of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) applications on wind design of tall buildings and structures: Past, present and future», Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 74, p. 106828, sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cheng, J. K. Wong, y O. Mercan, «Evaluating the wind loads on high-rise buildings of various plan dimensions through numerical simulations», Engineering Structures, vol. 343, n.o 120981, 2025. [En línea]. [CrossRef]

- Haan F. L., Wang J., Sterling M., y Kopp G. A., «Experimentally estimating wind load coefficients for tornadoes – An alternative perspective», Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial AerodynamicsJournal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, vol. 251, n.o 105811, 2024. [En línea]. [CrossRef]

- Idrissi, H. El Mghari, y R. El Amraoui, «CFD simulation advances in urban aerodynamics: Accuracy, validation, and high-rise building applications», Results in Engineering, vol. 26, n.o 105148, 2025. [En línea]. [CrossRef]

- F. Liu, Y. Ren, L. Zhang, y X. Li, «Impact of super high-rise buildings on wind comfort and safety of pedestrian wind environment: A case study in Shanghai, China», Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 71, p. 106197, jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Pardo-del Viejo y S. Fernández-Rodríguez, «CFD with LIDAR applied to buildings and vegetation for environmental construction», Automation in Construction, vol. 167, p. 105710, nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Kikuchi et al., «Comparison of wind pressure coefficients between wind tunnel experiments and full-scale measurements using operational data from an urban high-rise building», Building and Environment, vol. 252, p. 111244, mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ANSYS, Inc, «Capítulo 4: Turbulencia», Ansys Fluent R2 2024. Accedido: 13 de enero de 2025. [En línea]. https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/public/account/secured?returnurl=/Views/Secured/corp/v242/en/flu_th/flu_th_sec_turb_kw_sst.html.

- M. Fernández, Técnicas numéricas en ingeniería de fluidos : introducción a la dinámica de fluidos computacional (CFD) por el método de volúmenes finitos. Barcelona: Reverté, 2012.

- N. Fatchurrohman y S. T. Chia, «Performance of hybrid nano-micro reinforced mg metal matrix composites brake calliper: simulation approach», IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 257, p. 012060, 2017.

- «Numerical evaluation of wind effects on a tall steel building by CFD (2007).».

- J. M. Guevara Díaz, «Cuantificación del perfil del viento hasta 100 m de altura desde la superficie y su incidencia en la climatología eólica», Terra Nueva Etapa, vol. 29, n.o 46, pp. 81-101, 2013.

- Kubilay, A. Rubin, D. Derome, y J. Carmeliet, «Wind-comfort assessment in cities undergoing densification with high-rise buildings remediated by urban trees», Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, vol. 249, p. 105721, jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- «CFD simulation of wind-induced pressure coefficients on buildings with and without balconies.pdf».

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), Eurocode 1: Actions on structures — Part 1-4: General actions — Wind actions. 2005.

| Title | Comment | Ref |

| Evaluating the wind loads on high-rise buildings of various plan dimensions through numerical simulations. |

Checks the functionality of CFD in de capture of pressure coefficients high-rise buildings by simulations WMLES, are more precise than models RANS. |

[18] |

| Experimentally estimating wind load coefficients for tornadoes – An alternative perspective. |

Explain the importance of turbulence, and what is the relation with the applied loads on a sur-face or structure. |

[19] |

| A technical review of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) applications on wind design of tall buildings and structures: Past, present and future | Parameters such as velocity profile, mean pressure turbulence intensity profile, turbulence model and solution method influence the pressure for obtaining pressure coefficients on a surface. The LES model is more accurate than RANS but requires higher computational costs. |

[17] |

| CFD simulation advances in urban aerodynamics: Accuracy, validation, and high-rise building applications | Turbulence models such as k-ε-RNG and SST-ω-Standard were compared, including parameters like kinetic energy and the dissipation rate. To validate this research, wind tunnels studies were used. The result was that both models are reliable, but the k-ε model requires lower computational cost. | [20] |

| Parameter | value |

| Inlet velocity | 1.51 m/s |

| Outlet pressure | 0 Pa |

| Wall | No-slip |

| Air density | 1.255 kg/m3 |

| Air viscosity | 1.5x10-5 m2/s |

| Parameter | value |

| Water | 0.13 |

| Grass | 0.14-0.16 |

| Crops and shrubs | 0.20 |

| Forests | 0.25 |

| Urban area | 0.40 |

| Parameter | value |

| Inlet velocity | 1.51 m/s |

| Outlet pressure | 0 Pa |

| Wall | No-slip |

| Air density | 1.255 kg/m3 |

| Air viscosity | 1.5x10-5 m2/s |

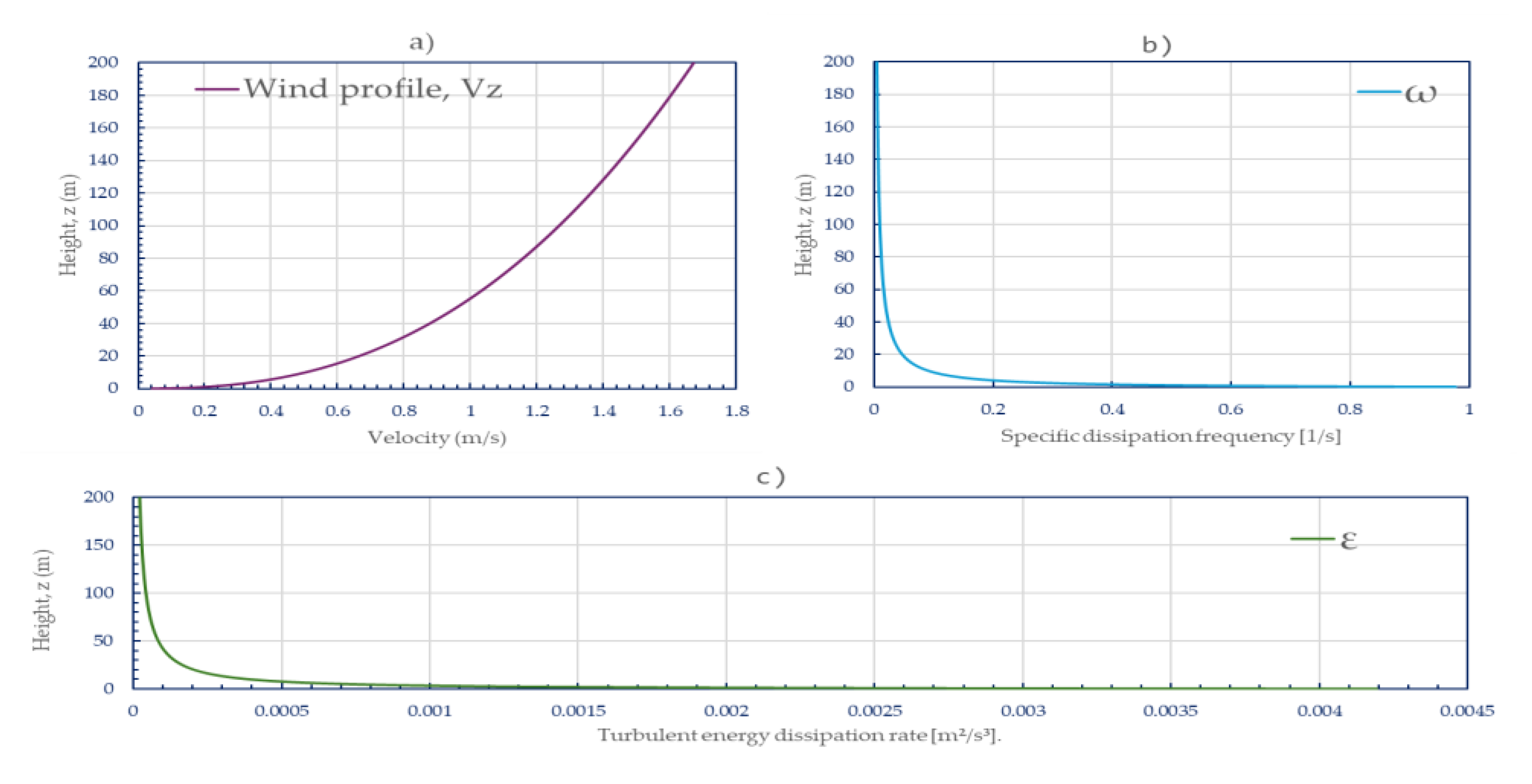

| Wind velocity | (equation 2) |

| Kinetic energy | (equation 3) |

| Turbulent energy dissipation rate | (equation 4) |

| Specific dissipation frequency | (equation 5) |

| Friction velocity | (equation 6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).