Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Study

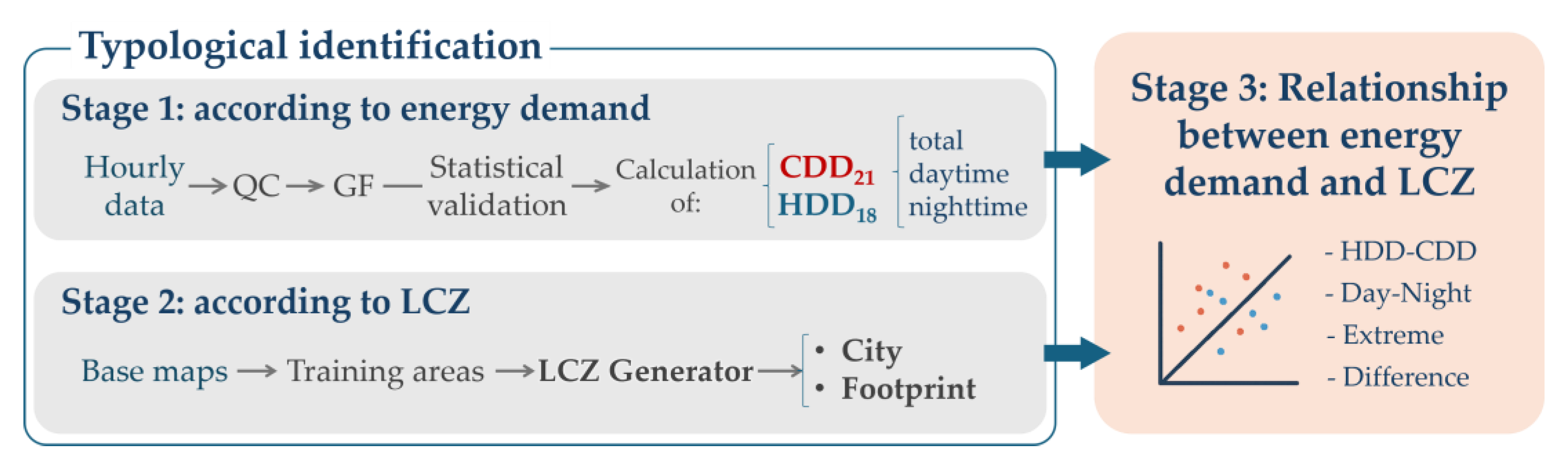

3. Methodology

4. Typological Identification According to Energy Demand

4.1. Data Processing and Verification

4.1.1. Data Quality Control

- Values outside the range of -7 °C to 25 °C during winter 2024/2025 and from 7 °C to 47 °C in summer 2025. These ranges correspond to ±5 °C relative to the absolute minimum and maximum temperatures recorded by the city’s AEMET station during the period in question [61].

- Hourly records with variations exceeding 9 °C compared to the previous one.

- Hourly values repeated for five or more consecutive hours.

- Hourly values that deviate more than four standard deviations from the average of the remaining stations.

4.1.2. Data Gap Filling

- Days with missing data for at least four consecutive hours in more than half of the stations.

- Days with at least nine consecutive hours without records coinciding with the period when daily maximum or minimum temperatures are typically observed.

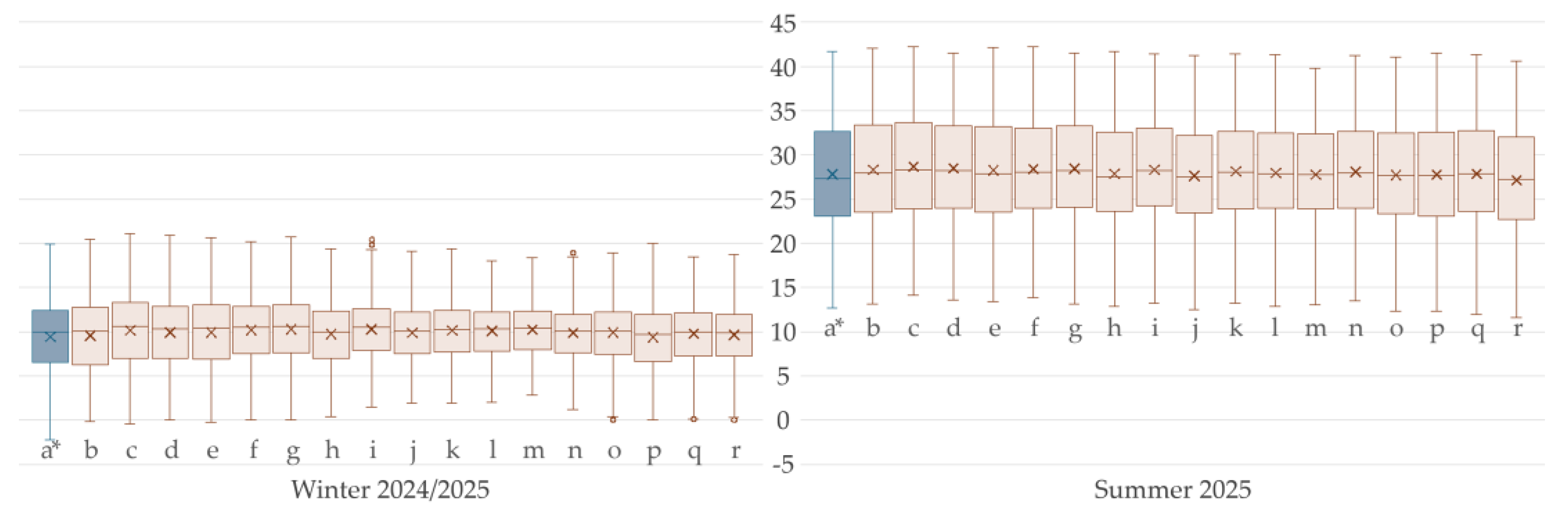

4.1.3. Statistical Analysis of the Dataset

4.2. Calculation and Analysis of HDD and CDD

- Balanced total thermal demand: the mean total demand is similar between climate periods (mean HDDtotal = 645 °C·day vs. mean CDDtotal = 657 °C·day), indicating that the average energy required for heating and cooling falls within the same order of magnitude (approximately 600–700 °C·day), with only a 2% difference between them.

- Coherent day/night distribution: all stations exhibit higher HDD at night than during the day, and conversely, higher CDD during the day than at night. This behavior is expected due to nocturnal temperature decreases and diurnal increases. Consequently, the highest energy demands occur during the most thermally severe periods: winter nights and summer days. The energy demand values reflect these constrasts, with summer days and winter nights (CDDday and HDDnight: 700–900 °C·day) showing nearly twice the demand observed during summer nights and winter days (HDDday and CDDnight: 325–550 °C·day).

- High spatial and temporal variability: a significant variability in energy demand is observed across stations, with differences exceeding 10% in all periods, being more pronounced in summer (CDDtotal: 15%) than in winter (HDDtotal: 11%). This variability also exhibits opposite behaviors depending on the season: in winter, dispersion is greater during the day (HDDday: 22%), whereas in summer it intensifies at night (CDDnight: 28%).

- More pronounced day–night contrast in summer: the mean difference in demand between daytime and nighttime is larger in summer (411 °C·day) than in winter (278 °C·day), indicating higher thermal stability during the colder season. The minimum difference is 177 °C·day in winter and 347 °C·day in summer. However, the relative difference between the maximum and minimum values across the local network is higher in winter (53%) than in summer (29%), highlighting substantial spatial variability in heating demand across neighborhoods.

5. Typological Identification According to LCZs

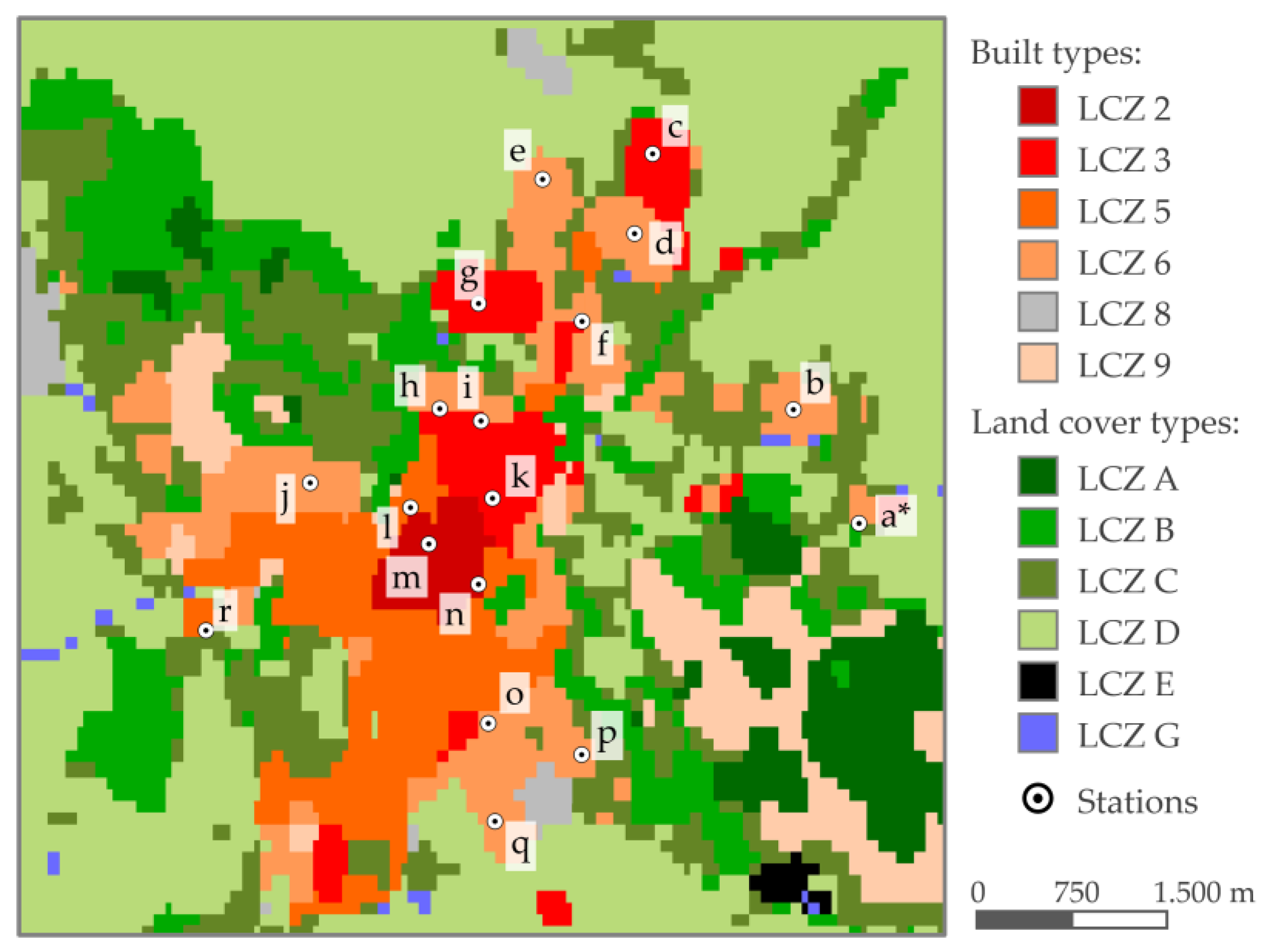

5.1. Identification Within the City

- LCZ 5: mid-rise buildings (3–9 floors) in open areas with vegetation, located mainly in the central, southern, and western sectors of the city.

- LCZ 6: low-rise buildings (1–3 floors) in open and vegetated areas, distributed across the urban periphery.

- LCZ 3: compact urban areas with low-rise buildings and sparse vegetation, found in the city center and in some northern and southern districts.

- LCZ 2: dense mid-rise buildings with low vegetation cover, concentrated in the central core.

- LCZ 8: paved surfaces or extensive low-rise constructions with little vegetation, present in industrial zones in the north, west, and south.

- LCZ 9: small or medium-sized buildings dispersed within natural areas featuring abundant vegetation and scattered trees, mainly in the southeast.

- LCZ A: areas with dense tree cover, corresponding to forested sectors or specific urban parks.

- LCZ B, C, and D: sparsely distributed trees, shrubs, and low vegetation or grass with limited tree cover, respectively, typically occurring heterogeneously in agricultural zones or urban parks. The identification model exhibited some difficulty distinguishing between classes B and C due to their similarity and spatial proximity within the city.

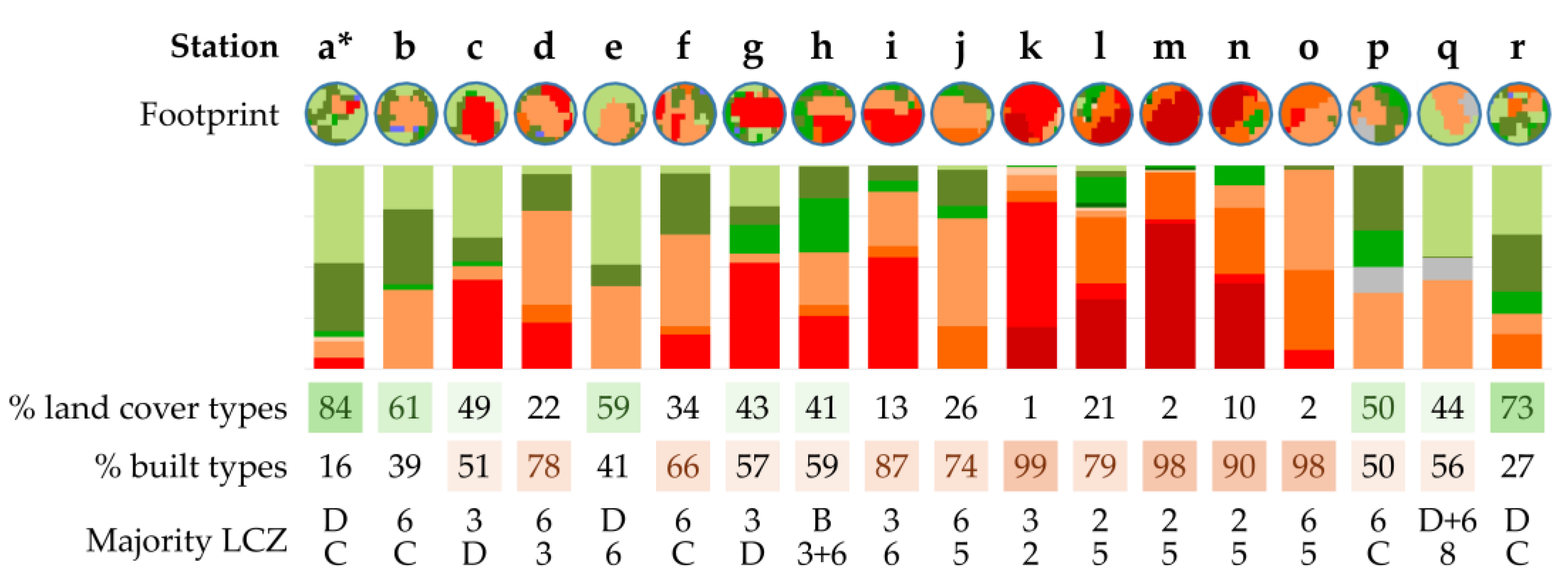

5.2. Identification Within the Footprints

- The predominant land cover types, with percentages reaching 84% and 73%, correspond to peripheral rural areas (station “a*”) and to urban expansion zones located along the city’s periphery (station “r”).

- Footprints with land cover percentages between 50% and 70% are predominantly characterized by LCZ D or LCZ C, combined with LCZ 6 urban areas. The presence of these footprints has been identified in peripheral sectors, specifically in the eastern (station "b"), northern (station "e"), and southern (station "p") regions.

- The highest percentages of built-up types (>90%) occur in the stations located within the urban center (“k”, “m”, “n”, and “o”).

6. Correlation Between Previous Typological Identifications: LCZ and Energy Demand

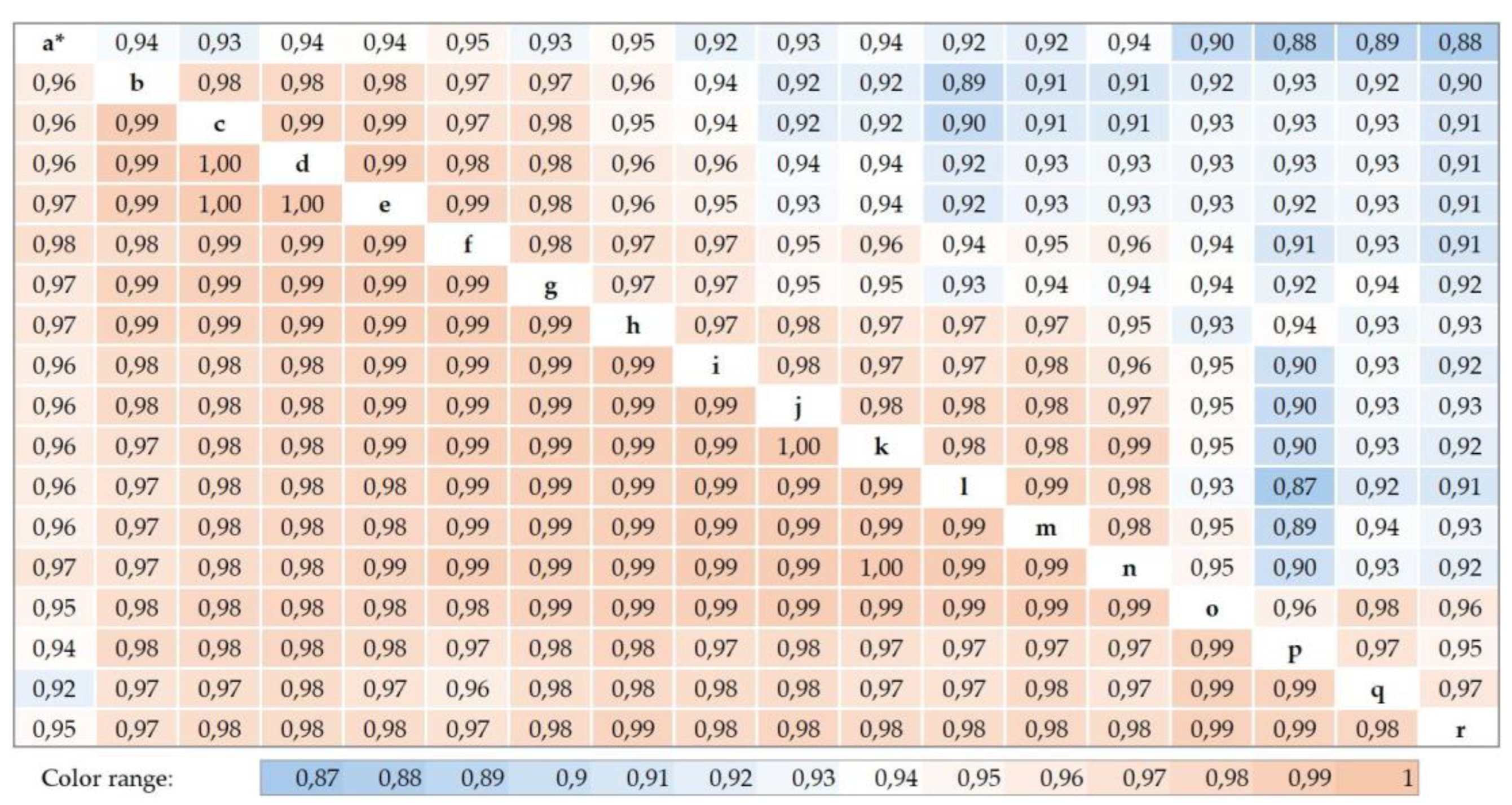

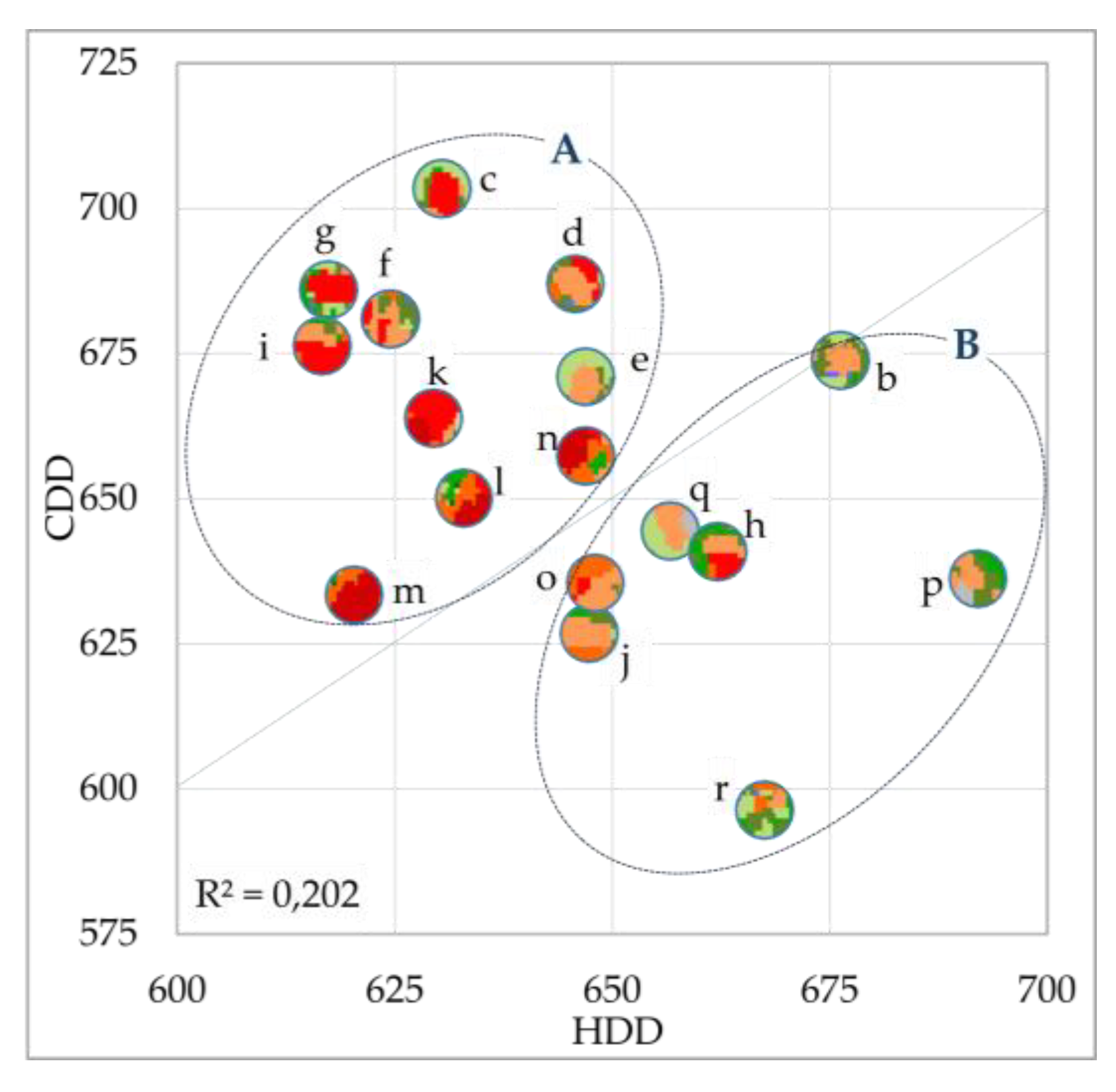

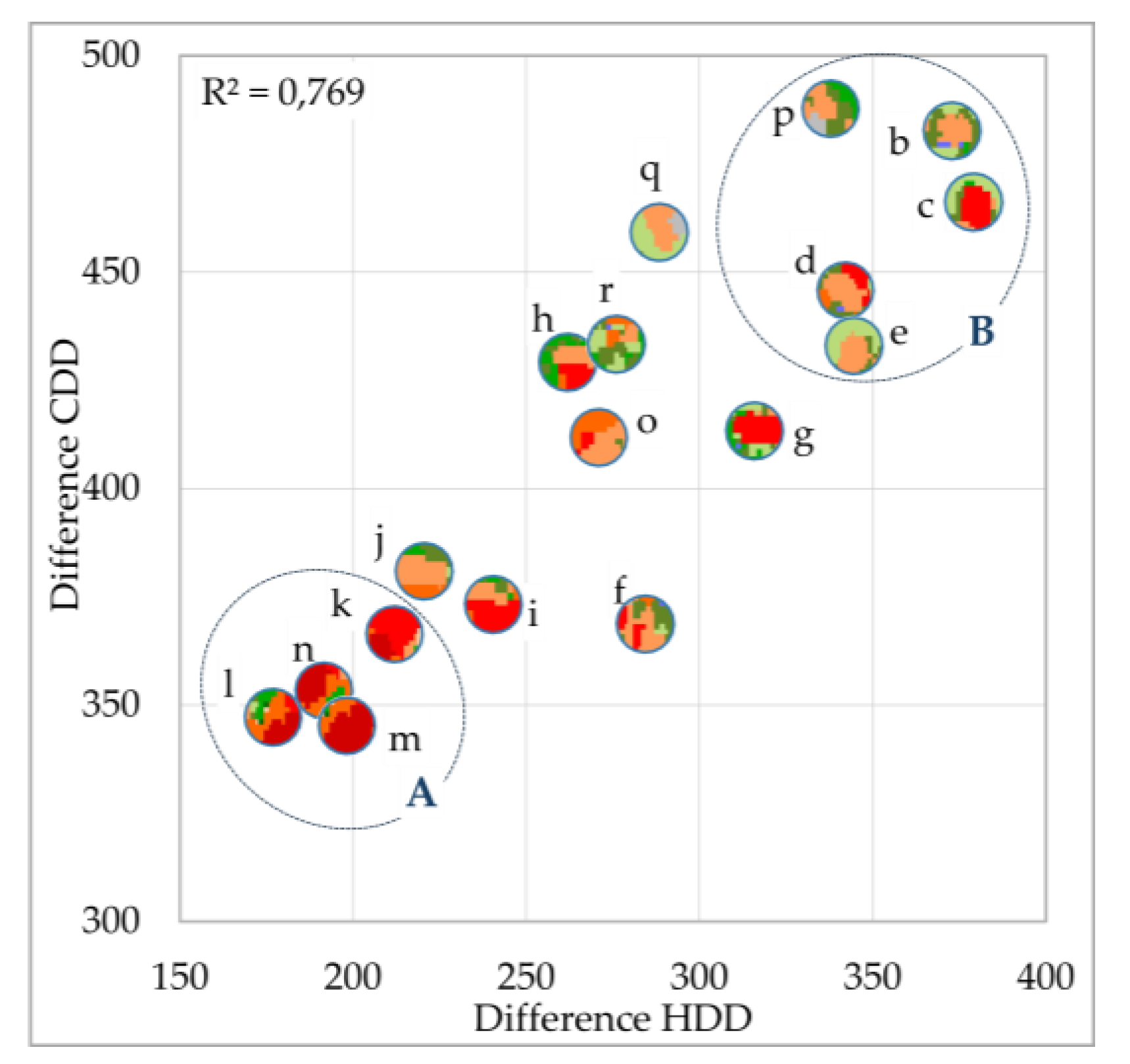

6.1. Globally Correlation Between Climate Periods

- Group A (stations “c”, “d”, “e”, “f”, “g”, “i”, “k”, “l”, “m”, and “n”): The analysis of these stations indicates that the cooling demand values are, on average, 6% higher (40 °C·day) than the heating demand. The smallest difference (1%) is recorded at station “n”, while the largest (12%) occurs at “c”. This group corresponds to areas located in the central and northern parts of the city, characterized by a high presence of built-up LCZ types and dominant LCZ classes 2 and 3.

- Group B (stations “b”, “h”, “j”, “o”, “p”, “q”, and “r”): These stations exhibit heating demand values that are, on average, 4% higher (28 °C·day) than the cooling demand. The largest difference (11%) is observed at station “r”, whereas the difference at station “b” is negligible. These stations are located in peripheral areas in the eastern, western, and southern regions of the city, characterized by a substantial presence of vegetation and the predominance of LCZ classes D and 6.

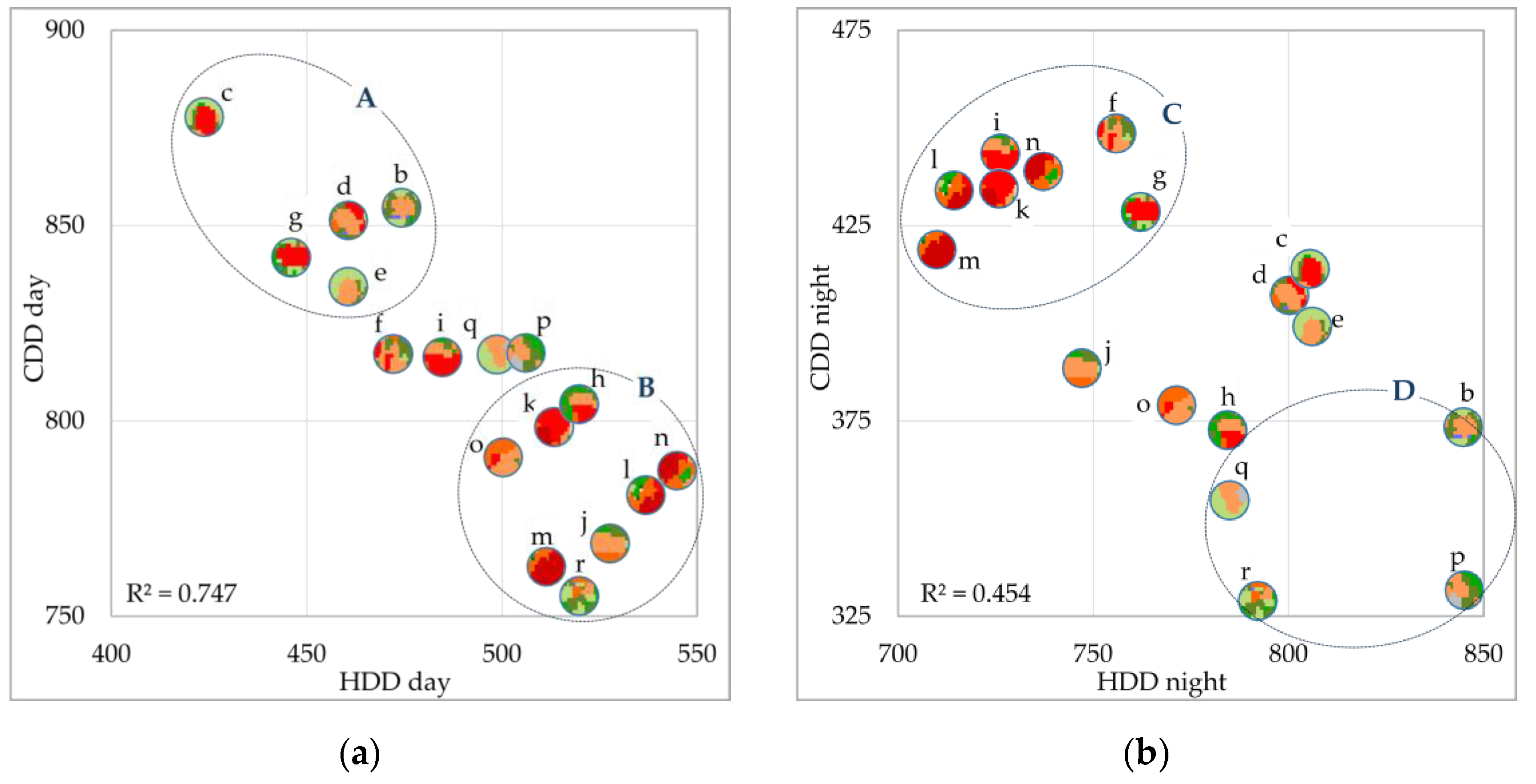

6.2. Hourly Correlation Between Climate Periods

- Group A (stations “c”, “b”, “d”, “e”, and “g”): This group represents the warmest daytime areas. Cooling demand is, on average, 5% above the mean value of the local network, with individual increases ranging from 3% at station “e” to 8% at “c”. Conversely, heating demand is, on average, 8% below that of the network, with reductions ranging from 4% at station “b” to 14% at “c”. These stations correspond to peripheral neighborhoods mainly in the northern part of the city, featuring a balanced presence of land cover and built-up LCZ types, with dominant classes LCZ 3 and 6.

- Group B (stations “j”, “l”, “m”, “n”, “r”, “h”, “k”, and “o”): This group represents the coolest daytime areas, with an average cooling demand that is 4% below the mean of the local network. The range of values is from 1% at station “h” to 7% at “r”. Likewise, the heating demand remains 6% above that of the network, spanning from 1% at “o” to 10% at “n”. This group comprises highly diverse areas but mainly includes central urban zones with high percentages of built-up LCZ types (74–99%) and dominant LCZ classes 2, 6, and 5.

- Group C (stations “f”, “g”, “i”, “k”, “l”, “m”, and “n”): These stations represent the warmest nighttime areas. Cooling demand exceeds the network average by 9%, with individual deviations between 4% at station “m” and 13% at “f”. In contrast, heating demand falls 5% below the network mean value, with individual reductions spanning from 1% at “g” to 8% at “m”. These stations are primarily situated within the dense and compact urban center, characterized by a mean built-up LCZ proportion of 83% and dominant classes 2 and 3.

- Group D (stations “b”, “p”, “q”, and “r”): This group corresponds to the coolest nighttime areas, with a cooling demand that is 13% less than the mean value of the network. The individual decreases fall between 7% at station “b” and 19% at “r”. Heating demand is, on average, 6% above that of the local network, with individual increases ranging from 2% at “q” to 10% at “p” and “b”. These stations are located in peripheral, sparsely urbanized neighborhoods, where land cover LCZ types account for 44–73%, and dominant classes are LCZ D and 6.

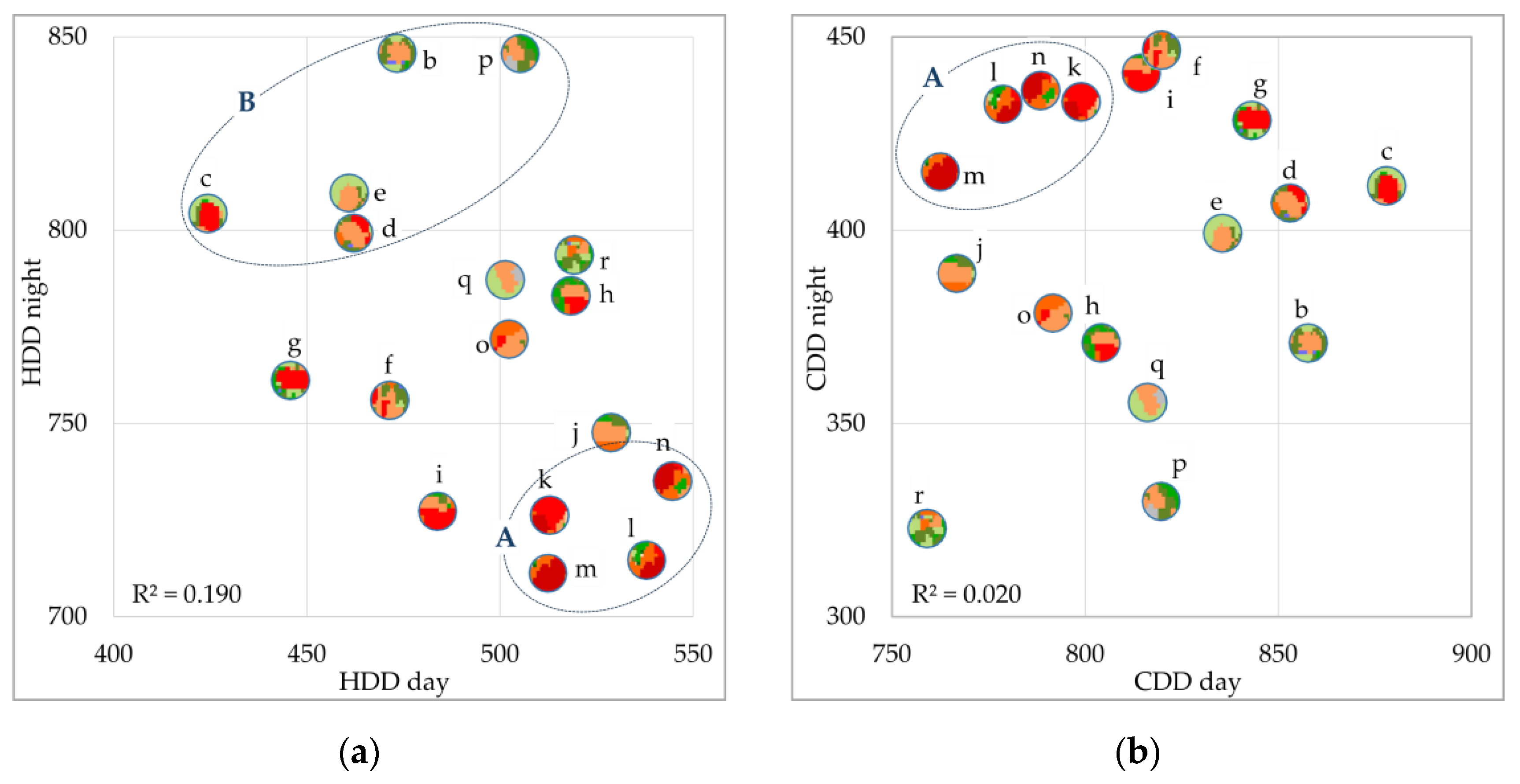

6.3. Seasonal Correlation Between Hourly Daytime and Nighttime Periods

- Group A (common to both seasons) (stations “k”, “l”, “m”, and “n”): These stations correspond to areas with relatively cool days and warm nights. Daytime heating demand is, on average, 7% above the overall mean (494 °C·day), with individual increases between 4% (stations “m” and “k”) and 10% (“n”). In contrast, daytime cooling demand falls 3.5% below the network mean value (400 °C·day), with individual reductions ranging from 1% at “k” to 6% at “m”. At nighttime, heating demand is, on average, 6.5% below the mean (772 °C·day), ranging from 5% at “n” to 8% at “m”. Cooling demand is 8% above the overall mean (411 °C·day), with increases from 4% at “m” to 10% at “n”. These stations are located in the dense, compact urban core, with low vegetation cover, a mean built-up LCZ proportion of 92%, and dominant LCZ class 2.

- Group B (stations “b”, “c”, “d”, “e”, and “p”): These stations correspond to areas with cold winter nights, as their nighttime heating demand exceeds the network average by 6% (772 °C·day), with individual increases spanning from 4% at stations “c”, “d”, and “e” to 10% at “b” and “p”. In the summer period, as well as during winter daytime, this group does not exhibit homogeneous behavior. These stations are located in peripheral zones in the north, east, and south of the city, with dominant LCZ class 6 and substantial vegetation cover (mean land cover LCZ proportion: 48%, range 22–61%).

- Group A (sensors “k”, “l”, “m”, and “n”), which matches the same Group A in Figure 8, encompasses the areas with the lowest daytime–nighttime variability in both summer and winter. This variability is below the overall network mean for both seasons: on average, 30% lower in winter (ranging between 23% at “k” and 36% at “l”) and 14% in summer (spanning from 16% at “m” and “l”, to 11% at “k”). The mean variability of this group is 195 °C·day in winter and 352 °C·day in summer.

- Group B (sensors “b”, “c”, “d”, “e”, and “p”), corresponding to the same Group B in Figure 8, includes the areas with the highest thermal variability relative to the mean, being higher than the network mean value for both seasons: on average, 28% higher in winter (ranging from 23% at “d” and “p” to 37% at “c”) and 12% in summer (between 5% at “e” and 18% at “p”). The mean variability of this group is 356 °C·day in winter and 462 °C·day in summer.

7. Discussion

- Areas with higher vegetation cover and permeable surfaces, primarily classified as land cover LCZs, tend to exhibit an augmented heating demand, particularly during nocturnal periods in winter. Simultaneously, these regions undergo comparatively cool summer nights, while daytime periods register elevated cooling demand, especially in more urbanized areas dominated by LCZ 6, leading to substantial day–night thermal variability. The heightened daytime cooling demand could be associated with increased solar exposure due to low building heights and the absence of shading. Conversely, nocturnal temperature drops in both seasons could be attributable to enhanced nocturnal cooling due to the low heat absorption of organic surfaces [68,69], as well as increased airflow in open and exposed peripheral areas.

- In contrast, zones with a higher proportion of built-up LCZs exhibit a contrasting pattern, characterized by cooler daytime temperatures, warmer nighttime temperatures, and reduced daily thermal variability. The cooler daytime temperatures could result from extensive shading in compact mid-rise sectors, characteristic of LCZ 2 and 5, which reduce solar heat gains on urban surfaces. The phenomenon of warm nights could be attributed to the absorption and storage of heat due to solar radiation on inorganic surfaces, particularly in areas dominated by LCZ 2 and 3. These areas feature high thermal inertia materials, narrow streets, and limited ventilation, retaining daytime heat and reducing nocturnal thermal loss [70]. The presence of anthropogenic heat sources could further reinforce this pattern, particularly in the densest urban centers [71], thereby contributing to the emergence of UHIs. Consequently, warmer nights reduce heating requirements but increase the risk of cumulative overheating.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEMET | Agencia Estatal de Meteorología |

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| CDD | Cooling Degree Days |

| CTE | Technical Building Code |

| DB-HE | Basic Document HE 'Energy Saving' |

| DD | Degree Days |

| DH | Degree Hours |

| EU | European Union |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| HDD | Heating Degree Days |

| HUZ | Homogeneous Urban Zones |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| LCZ | Local Climate Zones |

| LTD | Long-Term Drift |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| nZEB | Nearly Zero Energy Building |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| WMO | World Meteorological Organization |

| WUDAPT | World Urban Database and Access Portal Tools |

References

- IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. Standard 100-2024 ANSI/ASHRAE/IES 100; Energy and Emissions Building Performance Standard for Existing Buildings. Washington, 2024.

- de la U.E., C. Parlamento Europeo, DIRECTIVE (EU) 2023/1791 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 13 September 2023 on energy efficiency and amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (recast). 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de la U.E., C. Parlamento Europeo, DIRECTIVE (EU) 2024/1275 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 24 April 2024 on the energy performance of buildings (recast), 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj.

- Ministry of Environment, Decree 1010/2017 on the Energy Performance of New Buildings, Helsinki, 2017. Available online: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/lainsaadanto/saadoskokoelma/2017/1010 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure. Legislation Planning and Building Act (2010:900) Planning and Building Ordinance (2011:338), 2016. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/plan-och-bygglag-2010900_sfs-2010-900/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- C. and L.G. Ministry of Housing, Conservation of fuel and power: Approved Document L, England, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/conservation-of-fuel-and-power-approved-document-l (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Gesetz zur Einsparung von Energie und zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien zur Wärme- und Kälteerzeugung in Gebäuden (Gebäudeenergiegesetz – GEG), 2020. Available online: https://www.buzer.de/gesetz/14072/l.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Republic of Austria. Bundesgesetz, mit dem das Bundes-Energieeffizienzgesetz geändert wird; Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Energiegesetz (EnG), Switzerland. 2016. Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2017/762/de (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties, Besluit bouwwerken leefomgeving (Bbl), Netherlands, 2012. Available online: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2020-189.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Repubblica Italiana. Decreto interministeriale 26 giugno 2015 Applicazione delle metodologie di calcolo delle prestazioni energetiche e definizione delle prescrizioni e dei requisiti minimi degli edifici. Italy, 2015. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2015/07/15/15A05198/sg.

- Hellenic Republic, Ν. 4843/2021 (Φ.Ε.Κ. 193/A’ 20.10.2021): Τροποποιήσεις για τον ΚΕΝAΚ και άλλες διατάξεις για την ενεργειακή απόδοση των κτιρίων, Greece, 2021. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/n-48432021-fek-193a-20102021 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, Decreto-Lei n.o 101-D/2020, de 7 de dezembro, Portugal, 2020. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/101-d-2020-150570704 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ministère de la Transition écologique et de la Cohésion des territoires, Décret no 2021-1004 du 29 juillet 2021 relatif aux exigences de performance énergétique et environnementale des constructions de bâtiments en France métropolitaine, France, 2020. Available online: https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/politiques-publiques/reglementation-environnementale-re2020 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Agenda Urbana. Real Decreto 314/2006, de 17 de marzo, por el que se aprueba el Código Técnico de la Edificación, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2006-5515 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Agenda Urbana, Documento Básico HE Ahorro de energía. 2022.

- Hellenic Republic, Aπόφαση Aριθμ. ΔΕΠΕA/οικ. 178581/2017: Έγκριση Κανονισμού Ενεργειακής Aπόδοσης Κτιρίων (ΚΕΝAΚ), Greece, 2017. Available online: https://tdm.tee.gr/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/fek_12_7_2017_egrisi_kenak.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Presidenza della Repubblica Italiana. Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 26 agosto 1993, n. 412: Regolamento recante norme per la progettazione, l’installazione, l’esercizio e la manutenzione degli impianti termici degli edifici, Italy, 1993. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:presidente.repubblica:decreto:1993-08-26;412 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- e C., T. Ministério das Obras Públicas, Decreto-Lei n.o 80/2006, de 4 de abril, Portugal, 2006. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/80-2006-672456 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Deutsches Institut für Normung e. V. (DIN). Energetische Bewertung von Gebäuden – Berechnung des Nutz-, End- und Primärenergiebedarfs für Heizung, Kühlung, Lüftung, Trinkwarmwasser und Beleuchtung – Teil 10: Klimadaten für DeutschlandDeutschland, Germany, 2025. Available online: https://tienda.aenor.com/norma-din-ts-18599-10-2025-10-389788970 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Chapman, S.; Watson, J.E.M.; Salazar, A.; Thatcher, M.; McAlpine, C.A. The impact of urbanization and climate change on urban temperatures: a systematic review. Landsc Ecol 2017, 32, 1921–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.; Lauf, S.; Kleinschmit, B.; Endlicher, W. Heat waves and urban heat islands in Europe: A review of relevant drivers. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 569–570 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, V.; Bruno, S.; Fiorito, F. Comparative Analysis and Mitigation Strategy for the Urban Heat Island Intensity in Bari (Italy) and in Other Six European Cities. Climate 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zheng, W.; Yin, L. Urban heat islands and their effects on thermal comfort in the US: New York and New Jersey. Ecol Indic 2023, 154, 110765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, G.; Evangelisti, L.; Guattari, C.; Roncone, M.; Balaras, C.A. Space-time estimation of the urban heat island in Rome (Italy): Overall assessment and effects on the energy performance of buildings. Build Environ 2023, 228, 109878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, J.A.; Arrizabalaga, J.; Kupski, S.; Katzschner, L. Urban heat island in a coastal urban area in northern Spain. Theor Appl Climatol 2013, 113, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasilla, D.; Allende, F.; Martilli, A.; Fernández, F. Heat waves and human well-being in Madrid (Spain). Atmosphere (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrao, S.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Cuadrat, J.M.; Tejedor, E.; Saz Sánchez, M.A. Characterization of the UHI in Zaragoza (Spain) using a quality-controlled hourly sensor-based urban climate network. Urban Clim 2022, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Sobrino, J.A. Surface urban heat island analysis based on local climate zones using ECOSTRESS and Landsat data: A case study of Valencia city (Spain). International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2024, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, H.; Núñez-Peiró, M.; Sánchez-Guevara, C.; Neila, J. On the identification of Homogeneous Urban Zones for the residential buildings’ energy evaluation. Build Environ 2022, 207, 108451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, X.C.; Zhang, Y. Seasonal surface urban heat island analysis based on local climate zones. Ecol Indic 2024, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuzere, M.; Kittner, J.; Bechtel, B. LCZ Generator: A Web Application to Create Local Climate Zone Maps. Front Environ Sci 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, B.; Alexander, P.; Böhner, J.; Ching, J.; Conrad, O.; Feddema, J.; Mills, G.; See, L.; Stewart, I. Mapping Local Climate Zones for a Worldwide Database of the Form and Function of Cities. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2015, 4, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, B.; Daneke, C. Classification of Local Climate Zones Based on Multiple Earth Observation Data. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2012, 5, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local Climate Zones for Urban Temperature Studies. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Yang, H.; Jia, W. Urban Morphology Influencing the Urban Heat Island in the High-Density City of Xi’an Based on the Local Climate Zone. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, F.; Mills, G.; Poerschke, U.; Iulo, L.D.; Pavlak, G.; Kalisperis, L. A novel parametric workflow for simulating urban heat island effects on residential building energy use: Coupling local climate zones with the urban weather generator a case study of seven U.S. cities. Sustain Cities Soc 2024, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, B.; Jia, Y. Cooling Energy Challenges in Residential Buildings During Heat Waves: Urban Heat Island Impacts in a Hot-Humid City. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, F.; Najafian, P.; Salahi, N.; Ghiasi, S.; Passe, U. The Impact of the Urban Heat Island and Future Climate on Urban Building Energy Use in a Midwestern U.S. Neighborhood. Energies (Basel) 2025, 18, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Cui, X.; Tong, H. Combined impact of climate change and urban heat island on building energy use in three megacities in China. Energy Build 2025, 331, 115386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Mathur, J.; Garg, V. Assessment of climate classification methodologies used in building energy efficiency sector. Energy Build 2023, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE, ASHRAE Terminology, Degree Day, Https://Terminology.Ashrae.Org/?Entry=degree%20day. Available online: https://terminology.ashrae.org/?entry=degree%20day (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- D’Amico, A.; Ciulla, G.; Panno, D.; Ferrari, S. Building energy demand assessment through heating degree days: The importance of a climatic dataset. Appl Energy 2019, 242, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Bianco, V.; Scarpa, F.; Tagliafico, L.A. Heating and cooling building energy demand evaluation; a simplified model and a modified degree days approach. Appl Energy 2014, 128, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization, WMO. n.d. Available online: https://wmo.int/es (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, S.; Jia, G.; Li, H.; Li, W. Urban heat island impacts on building energy consumption: A review of approaches and findings. Energy 2019, 174, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoDatos, Coordenadas de Cáceres, España. 2025. Available online: https://www.geodatos.net/coordenadas/espana/caceres.

- Bernabé, A. Chazarra; Mariño, B. Lorenzo; Fresneda, R. Romero; Moreno García, J.V. Evolución de los climas de Köppen en España en el periodo 1951-2020; Madrid, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Heating; A.-C. Engineers. ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 169-2021: Climatic Data for Building Design Standards; ASHRAE. Atlanta, GA, 2021.

- MINISTERIO DE VIVIENDA Y AGENDA URBANA, Documento Básico HE. In Ahorro de energía; 2022.

- A. Meteo, Datos meteorológicos ASHRAE para Cáceres, España. 2025. Available online: https://ashrae-meteo.info/v2.0/?lat=39.4714&lng=-6.3389&place=’’&wmo=082610&si_ip=SI&ashrae_version=2021.

- Sánchez-Guevara, A.; Garmendia Arrieta, L.; Montalbán Pozas, B. Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades PID2022-138284OA-C32; OLADAPT: Olas de calor y ciudades: adaptación y resiliencia del entorno construido. 2023.

- T.S.C. Sensirion, Datasheet SHT3x-DIS www.sensirion.com. 2022.

- Lucas Bonilla, M.; Albalá Pedrera, I.T.; Bustos García de Castro, P.; Martín-Garín, A.; Montalbán Pozas, B. Comparing Monitoring Networks to Assess Urban Heat Islands in Smart Cities. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Law, Comfort Energetics: Thermal Comfort Under Energy Constraints 2013, 83–115. [CrossRef]

- Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET), Valores climatológicos normales: Cáceres; 2010.

- Beck, C.; Straub, A.; Breitner, S.; Cyrys, J.; Philipp, A.; Rathmann, J.; Schneider, A.; Wolf, K.; Jacobeit, J. Air temperature characteristics of local climate zones in the Augsburg urban area (Bavaria, southern Germany) under varying synoptic conditions. Urban Clim 2018, 25, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, D.; Bechtel, B.; Demuzere, M.; Kittner, J.; Meier, F. CrowdQC+—A Quality-Control for Crowdsourced Air-Temperature Observations Enabling World-Wide Urban Climate Applications. Front Environ Sci 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Medina, D.; Guerrero Delgado, Mc.; Sánchez Ramos, J.; Palomo Amores, T.; Romero Rodríguez, L.; Álvarez Domínguez, S. Empowering urban climate resilience and adaptation: Crowdsourcing weather citizen stations-enhanced temperature prediction. Sustain Cities Soc 2024, 101, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres; Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET). Analisis estacional. 2025. Available online: Https://Www.Aemet.Es/Es/Serviciosclimaticos/Vigilancia_clima/Analisis_estacional?L=3469A.

- Time and Date AS, Sunrise, Sunset, and Daylength: Cáceres, Cáceres, Spain. 2025. Available online: Https://Www.Timeanddate.Com/.

- Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat). Energy statistics - cooling and heating degree days. 2024. Available online: Https://Ec.Europa.Eu/Eurostat/Cache/Metadata/En/Nrg_chdd_esms.Htm#.

- Oke, T.E. Initial guidance to obtain representative meteorological observations at urban sites; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Peng, L.L.H.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yao, L.; He, Y.; Xu, T. Impact of urban heat island on energy demand in buildings: Local climate zones in Nanjing. Appl Energy 2020, 260, 114279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J. Contribution of local climate zones to the thermal environment and energy demand. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, N.; Sharifi, A. Urban heat dynamics in Local Climate Zones (LCZs): A systematic review. Build Environ 2025, 267, 112225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zheng, H.; Liu, X.; Gao, Q.; Xie, J. Identifying the Effects of Vegetation on Urban Surface Temperatures Based on Urban–Rural Local Climate Zones in a Subtropical Metropolis. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15, 4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaab, J.; Meier, R.; Mussetti, G.; Seneviratne, S.; Bürgi, C.; Davin, E.L. The role of urban trees in reducing land surface temperatures in European cities. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, L.; Mu, K.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J. Urban heat island effects of various urban morphologies under regional climate conditions. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 743, 140589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Mughal, M.O.; Martilli, A.; Acero, J.A.; Ivanchev, J.; Norford, L.K. Numerical analysis of the impact of anthropogenic emissions on the urban environment of Singapore. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Herráez, G.; Martínez-Lastras, S.; Lagüela, S.; Martín-Jiménez, J.A.; Del Pozo, S. Morphological and Environmental Drivers of Urban Heat Islands: A Geospatial Model of Nighttime Land Surface Temperature in Iberian Cities. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgheznawy, D.; Eltarabily, S. The impact of sun sail-shading strategy on the thermal comfort in school courtyards. Build Environ 2021, 202, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G. On the linkage between urban heat island and urban pollution island: Three-decade literature review towards a conceptual framework. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 751, 141727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, M. Multi-scale analysis of surface thermal environment in relation to urban form: A case study of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustain Cities Soc 2023, 99, 104953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, N.Y.; Triyadi, S.; Wonorahardjo, S. Effect of high-rise buildings on the surrounding thermal environment. Build Environ 2022, 207, 108393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, K.-M.; Yuan, C.; Lai, A.; Yu, P.K.N. Relationship between pedestrian-level outdoor thermal comfort and building morphology in a high-density city. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 708, 134516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| % | a* | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r |

| W 1 | 96 | 94 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 86 | 90 | 95 | 68 | 79 | 88 | 94 | 95 | 93 | 90 | 95 | 79 |

| S 2 | 84 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 98 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 99 | 100 | 97 | 96 | 96 | 89 |

| HDD | CDD | |||||||

| Station | total | day | night | Dif *1 | total | day | night | Dif *1 |

| a* - AEMET | 687 | 546 | 807 | 261 | 634 | 763 | 419 | 344 |

| b | 676 | 474 | 847 | 373 | 675 | 856 | 373 | 483 |

| c | 630 | 424 | 804 | 380 | 704 | 878 | 414 | 464 |

| d | 646 | 461 | 802 | 341 | 687 | 853 | 409 | 444 |

| e | 647 | 460 | 806 | 346 | 672 | 834 | 401 | 433 |

| f | 625 | 471 | 755 | 284 | 681 | 819 | 450 | 369 |

| g | 618 | 446 | 763 | 317 | 687 | 843 | 429 | 414 |

| h | 662 | 519 | 784 | 265 | 642 | 804 | 373 | 431 |

| i | 616 | 485 | 727 | 242 | 677 | 817 | 443 | 374 |

| j | 648 | 529 | 748 | 219 | 626 | 768 | 389 | 379 |

| k | 630 | 514 | 727 | 213 | 663 | 800 | 434 | 366 |

| l | 633 | 537 | 714 | 177 | 650 | 780 | 433 | 347 |

| m | 620 | 512 | 711 | 199 | 633 | 763 | 416 | 347 |

| n | 648 | 544 | 736 | 192 | 657 | 788 | 439 | 349 |

| o | 647 | 501 | 771 | 270 | 635 | 790 | 378 | 412 |

| p | 691 | 506 | 847 | 341 | 636 | 818 | 331 | 487 |

| q | 657 | 501 | 788 | 287 | 645 | 818 | 357 | 461 |

| r | 667 | 520 | 792 | 272 | 595 | 757 | 325 | 432 |

| Mean ± SD | 645 ± 21 | 494 ± 34 | 772 ± 42 | 278 ± 65 | 657 ± 28 | 811 ± 35 | 400 ± 39 | 411 ± 48 |

| Difference*2 | 11% | 22% | 16% | 53% | 15% | 14% | 28% | 29% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).