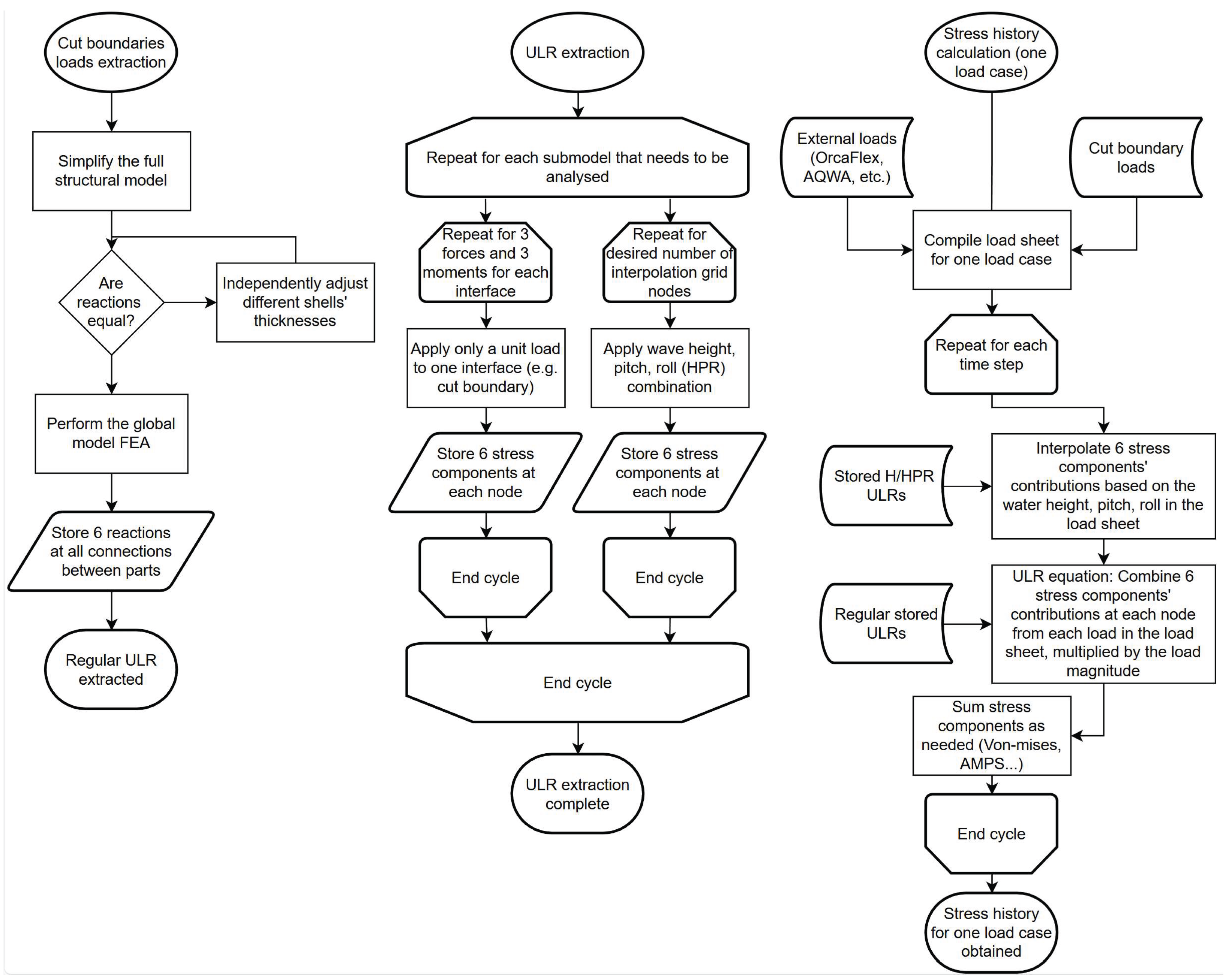

Unit Load Response

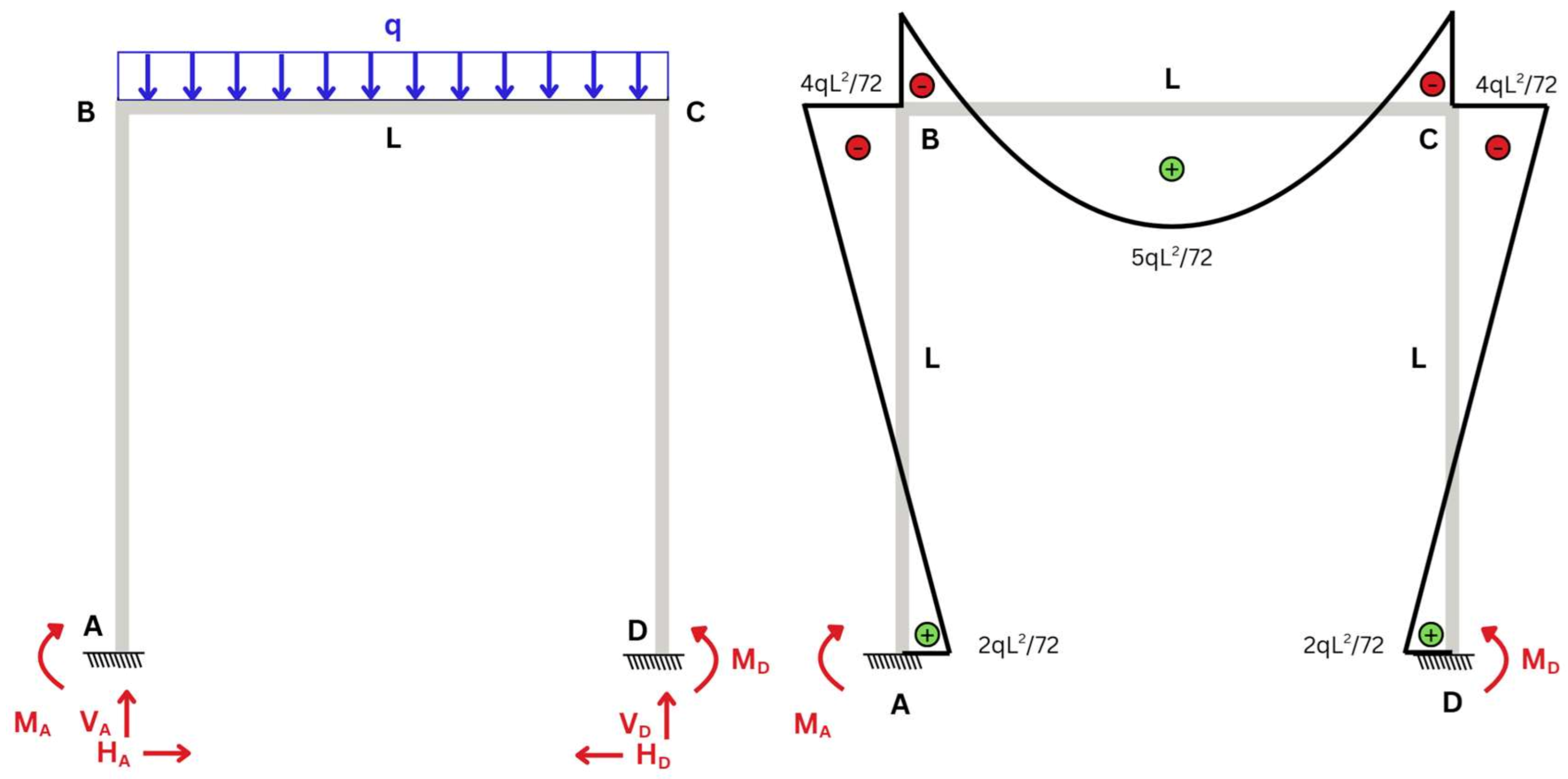

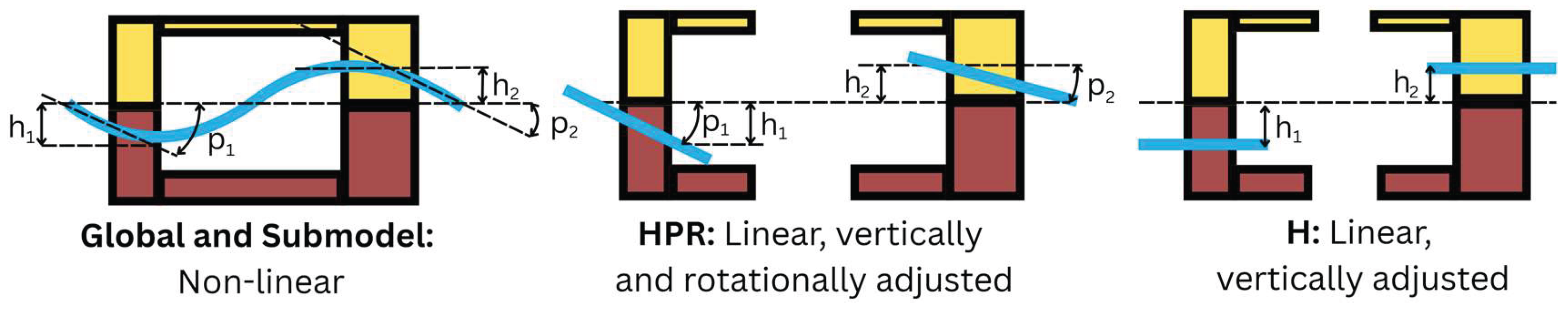

The (global) portal frame was re-analysed in Ansys Mechanical and benchmarked against the closed-form beam solution. The bending-moment distribution (

Figure 4) from FEM matches the analytical diagram, and

Table 1 summarises stress/moment agreement for beam- and shell-element models. To enforce a rigid-joint assumption in the shell representation, we introduced internal stiffeners at the beam–column connection. The stiffened shell model reproduces the analytical mid-span bending moment within 0.51%, confirming structural equivalence. The axial force in the beam model is 4810 N versus 5000 N analytically; the shear force is 100 N versus 0, reflecting formulation differences rather than modelling error. We then assembled a 3D frame from four identical 2D frames (

Figure 7), using 1 mm internal joining brackets in the shell model. For Beam 1, the 3D shell solution is the closest to the analytical result (

Table 1). Beam 2 uses the same section but a slightly different connection; because the hollow rectangular section is not symmetric with respect to both section axes, its response differs and lies outside the force-method assumptions. Accordingly, Beam 2 is validated by comparing shell and beam FEA only, which show close agreement. Finally, the 3D shell model reveals non-uniform stress over a given section/elevation (e.g., along the top plate), a shear-lag effect naturally captured by finite elements but not represented in the baseline analytical solution (and not required for the present checks).

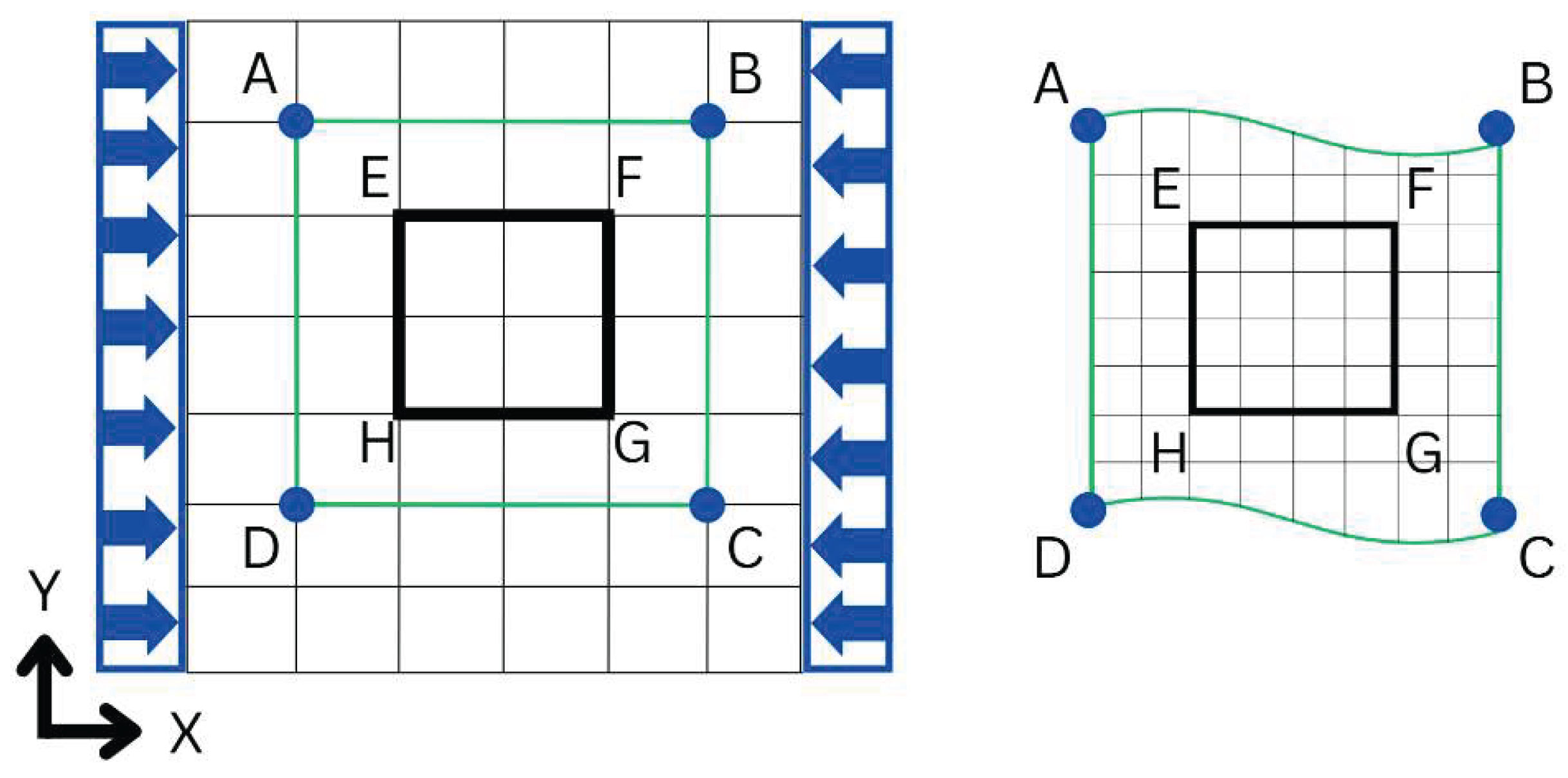

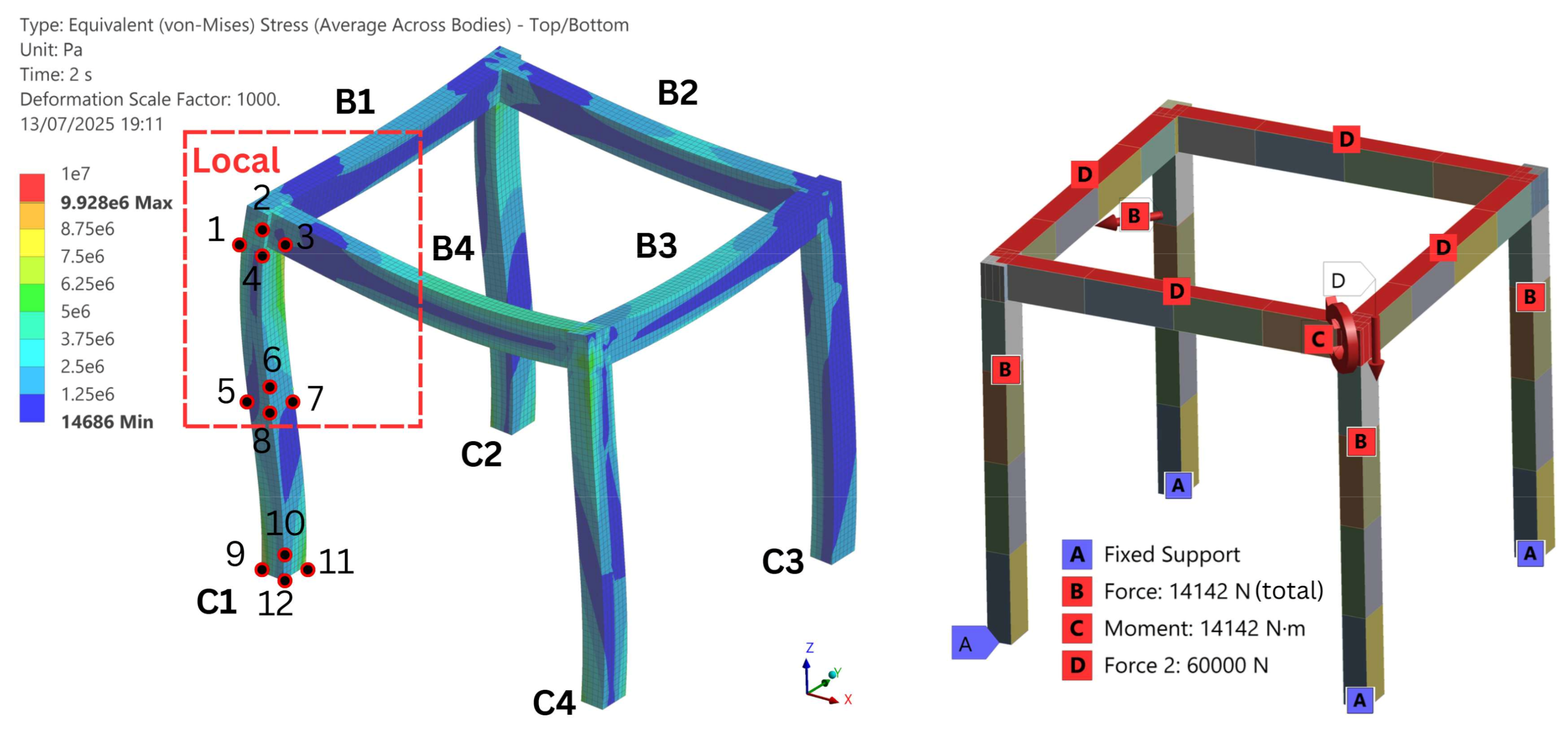

With the global 3D beam and shell frames validated against the analytical solution, we proceed to submodelling and ULR modelling under a composite load case that captures (i) forces entering and leaving the local domain, (ii) both distributed and point loads, and (iii) axial, shear, bending, and torsional loads (

Figure 7, right). Verification is based on equivalent von Mises stresses at 12 preselected hot spots—corner stress concentrations at the beam–column joint (Top), mid-height of the column (Mid), and the fixed support (Bot) as shown in

Figure 7—reflecting strength and fatigue-critical locations. The global shell model is taken as the reference for error evaluation, as it best represents the physical structure. For submodelling, we employ fixed support submodels with three load-application schemes: (i) reactions extracted from the global beam model; (ii) reactions extracted from the global shell model; and (iii) as in (ii) but using rigid remote-point cut boundaries.

Table 2 summarizes the resulting stress errors across all points. Comparing results obtained using loads extracted from beam and shell global models, the shell load submodel shows consistently good results in all top, middle, and bottom sections, while the beam load model only shows good results in the middle (far from the connection and support). This difference in extracted loads from the shell and beam global models is seen in

Table 3; while the main forces are the same, there can be a significant difference in the small-magnitude MX and MZ moments due to the formulations of beam and shell elements. This difference is amplified when multiplied by the ULR.

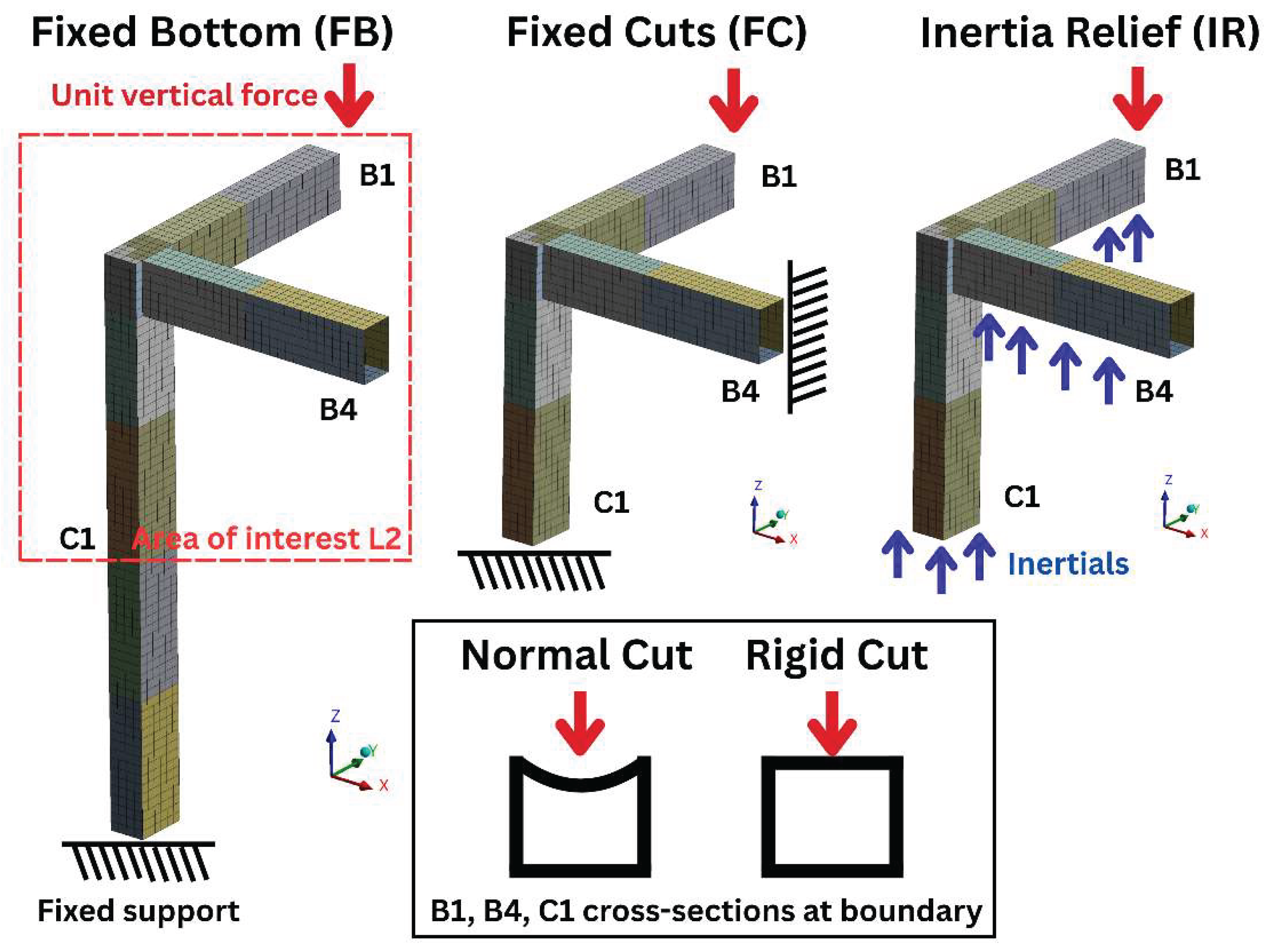

To understand the sources of the

Table 2 errors, we decompose them into three contributors—(i) ULR boundary-condition error, (ii) submodelling boundary-proximity error, and (iii) distributed-load error—and examine them in isolation, beginning with the ULR boundary condition. In the global model, the frame is fixed at the base of C1; however, this support is outside the local domains used to compute ULRs, so an auxiliary boundary condition is required.

Figure 8 defines three candidate boundary conditions, and for each boundary, the cut section is modelled either as deformable or as artificially rigid via a multi-point constraint (remote point in ANSYS), yielding six boundary-condition combinations. All models are evaluated under four load cases: (i) top-surface distributed load only, (ii) the combined loading as shown in

Figure 7, (iii) the point moment only as shown in

Figure 7, and (iv) the combined case (ii) with the distributed load removed. For every node, equivalent von Mises stresses from the local models are compared to the global shell reference, and the signed percentage errors are plotted in

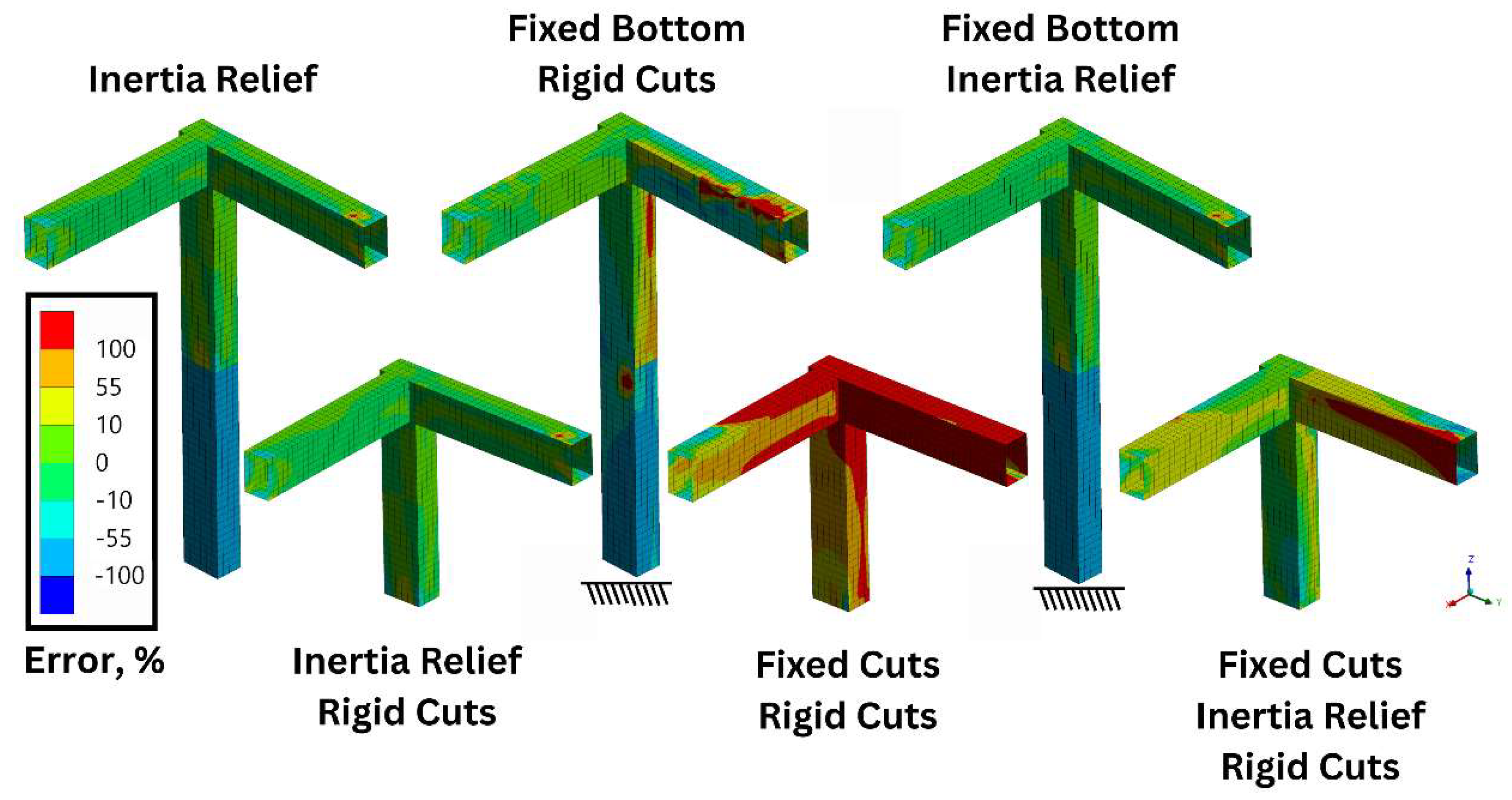

Figure 9.

For screening, the correct ordering of hot spots often matters more than exact stresses. To evaluate whether the proposed approach could incorrectly rank nodes, we used Kendall’s τ-a, an established rank-correlation metric [

34], alongside stress errors.

Nodes near the boundaries were excluded from τ-a to remove boundary effects. From the results in

Table 4, inertia-relief boundary conditions perform better than the other conditions, yielding a 1.86% median absolute error across the four load cases. With inertia relief enabled, the choice of cut-boundary location and whether the section was modelled deformably or via a remote-point constraint had negligible influence. In contrast, a fixed-bottom condition required a substantially larger submodel and higher cost; accordingly, we select simple inertia relief for the case study. Load-case sensitivity further shows that, when distributed forces are absent, stress errors are ≈0% and node rankings are preserved (τ-a≈1); as the proportion of distributed loading increases (combined < distributed), stress errors rise and ranking fidelity degrades, identifying distributed loads as the principal challenge for ULR, addressed next.

The large gap between the median and mean errors in

Table 4 may arise from boundary-condition artefacts—unphysical stress spikes localised near the cut, as shown in

Figure 9—so model cuts should be placed well away from the region of interest (the beam joint).

Figure 8 quantifies boundary-proximity effects by tracking von Mises stresses at hot-spot nodes (region of interest) and at four bottom-corner control nodes (expected to be insensitive) under seven unit-load cases: six global end loads (three 1 N forces and three 1 Nm moments applied at the far end of B4) and a 1 Pa uniform pressure on the top surface (the same basis used for ULR extraction). Cut loads are sampled at multiple distances and applied to a fixed-bottom local model (with pressure also applied locally). Results show near-zero stress errors for all non-pressure unit loads—even at the minimum boundary distance—with errors increasing as the cut moves closer, while the bottom control nodes remain unaffected. In contrast, the distributed-pressure case exhibits non-zero, irregular errors even for distant cuts, motivating the alternative treatment of pressure ULRs development.

Figure 10.

Stress results for global and smallest local model when loaded by distributed pressure load. Green lines indicate cuts where loads are exported to local models.

Figure 10.

Stress results for global and smallest local model when loaded by distributed pressure load. Green lines indicate cuts where loads are exported to local models.

Table 5.

Error in stress vs cut boundary distance from 7 unit loads.

Table 5.

Error in stress vs cut boundary distance from 7 unit loads.

| |

AVERAGE ERROR ACROSS 4 TOP POINTS |

AVERAGE ERROR ACROSS 4 BOTTOM POINTS |

| DISTANCE |

FX |

FY |

FZ |

MX |

MY |

MZ |

P |

FX |

FY |

FZ |

MX |

MY |

MZ |

P |

| 100% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 80% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

-0.03% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.45% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.43% |

| 60% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

-0.01% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.08% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.07% |

| 40% |

0.00% |

0.02% |

0.00% |

0.23% |

0.00% |

0.02% |

0.71% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.71% |

| 20% |

0.00% |

0.39% |

0.00% |

0.81% |

0.00% |

0.40% |

0.34% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.36% |

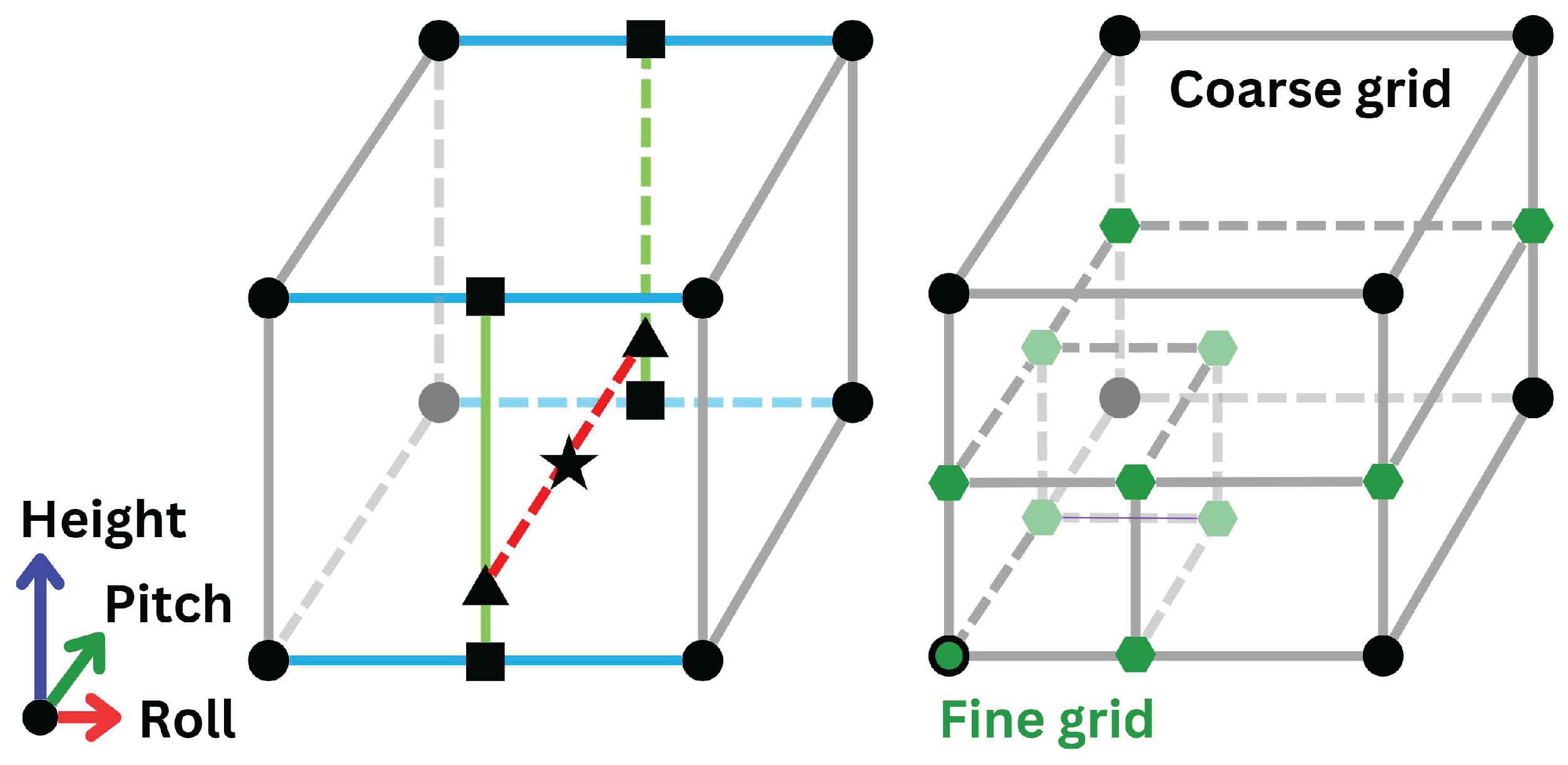

Wave and Static Pressure Interpolation

To isolate interpolation effects, we consider wave pressure only and keep the local-model boundary conditions identical to the reference submodel. We apply the HPR procedure to the 3D frame by parameterizing the free-surface state with three variables—heave, pitch, and roll. The frame stands half-submerged (1.5 m); zero heave corresponds to the nominal waterline at 1.5 m, and heave is between -1.5 m and 1.5 m. Pitch and roll vary within −6° and 6°. A tensor grid of ULRs is precomputed over this domain using 0.5 m and 3° spacing for heave and pitch/roll, respectively, producing 175 wave-pressure ULRs (versus 22 in the original non-pressure study).

Table 6.

ULR interpolated stress result error for the 3D frame loaded by hydrostatic pressure.

Table 6.

ULR interpolated stress result error for the 3D frame loaded by hydrostatic pressure.

| NODE 1 |

A H1P6R6 |

0% |

NODE 3 |

A H1P6R6 |

0% |

| |

B h-0.25p5r2 |

2% |

|

B h-0.25p5r2 |

2% |

| |

C h4p8r0 |

3003% |

|

C h4p8r0 |

867% |

| |

D h0.75p-4.5r1.5 |

-2% |

|

D h0.75p-4.5r1.5 |

-1% |

| NODE 2 |

A h1p6r6 |

0% |

NODE 4 |

A h1p6r6 |

0% |

| |

B h-0.25p5r2 |

-1% |

|

B h-0.25p5r2 |

-1% |

| |

C h4p8r0 |

2184% |

|

C h4p8r0 |

958% |

| |

D h0.75p-4.5r1.5 |

-2% |

|

D h0.75p-4.5r1.5 |

-2% |

The parameter values and corresponding pressure distributions for the four selected cases are shown in

Figure 11. During analysis, if the queried state matches a tabulated point exactly, the corresponding ULR is used directly (Case A); otherwise, states within the grid are obtained by tri-linear interpolation from the nearest tabulated ULRs (Case B and D), and states outside the grid are evaluated by linear extrapolation along the nearest coordinate directions (Case C). Table 10 compares these ULR-based stresses against solutions with the exact applied pressure. Case A yields 0% error, confirming the correctness of the ULR setup. Interpolation is accurate: a typical interior query (Case B) incurs near 1% error, while a deliberately worst-positioned mid-cell query (Case D) reaches 2%—the expected upper bound given the chosen grid spacing. By contrast, extrapolation performs poorly: a far out-of-grid query (Case C) exhibits an error on the order of 10

3%. Hence, for hydrostatic pressure loads, the parameter grid must cover the full operating envelope to avoid extrapolation.

It is worth noting that interpolation is only one strategy for handling distributed loads. An alternative—commonly used in the oil and gas sector but largely undocumented in the scientific literature—is a global beam pressure–distribution approach: (1) construct an equivalent global beam model from the global shell model with matched cross-sectional stiffness; (2) map the time-varying wave pressure from AQWA (computed on the global shell) to this equivalent model at each time step; and (3) convert the shell pressures into line loads along the pontoons’ longitudinal axes and along the submerged portions of the columns (top, sides, and/or bottom) at each time step, and treat these line loads as additional ULRs. Having separately quantified interpolation, cut-boundary proximity, and boundary-condition errors, the overall expected stress error can be estimated via standard root-sum-of-squares propagation [

35] under an approximate independence assumption. Using median deviations of 2.0%, 1.86%, and 1.45%, respectively, the approximate expected combined error is 3.09%. In the next section, geometry error will also be introduced due to global model simplification.