1. Introduction

The geometric and structural parameters of the railway superstructure change over time due to the influence of operational loads and climatic effects. Slovak Railways, as the highest authority responsible for the safety and quality of the national railway lines, controls the regular implementation of railway diagnostics to prevent accidents caused by their inadequate quality. Suppose the permissible elasticity limits of the tested railway body are exceeded, permanent deformations of the track geometry occur, and this causes discomfort for passengers and an increase in operational and maintenance costs. The railway monitoring companies have a wealth of reliable, accurate technology for determining relative changes in the structure. However, the track's spatial changes relative to railway benchmarks, as determined by coordinates in the global national system, can only be defined using geodetic methods. The railways' modernisation has increased operating speeds and introduced new structural elements to the track body, placing greater demands on track maintenance and diagnostics. The current measurement railway technologies reflect the requirements for the safe, fast, and precise determination of track geometric and structural parameters. The diagnostics wagon fully meets these requirements, but it is primarily intended for large-scale railway diagnostics due to its high operating costs. It is characterised by fast, continuous data recording using contact sensors mounted on the vehicle's underside and by direct online transmission to the evaluation unit. Instead of the vast and expensive diagnostics wagons, low-cost, portable mobile lidar mapping systems or manual measuring vehicles are used for precise, reliable track measuring within a smaller diagnostics range. Geodetic measurement methods are also adapted for the continuous monitoring of the railway line's spatial position. Robotic total stations, terrestrial and aerial laser scanners, or the kinematic method of a global navigation satellite system; all these techniques are considered suitable for railway diagnostics thanks to their ensured accuracy. The inertial measurement unit (IMU) with the automatic tilt reduction made a significant contribution to the quality of data acquisition by receivers of the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and the reflecting prisms used in the spatial polar method. Recently, the popularity of satellite interferometry in geodetic applications has increased due to its ability to obtain detailed information about the Earth with sub-centimetre accuracy by combining special corner reflectors, GNSS observations, and precise levelling measurements. The focus of the paper is on processing the output of the terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), the method applied in the railway diagnostics process. The advantage of combining TLS with the static GNSS method lies in its high resolution and accuracy, making it preferable to close-range aerial photogrammetry. The obtained point cloud represents a dataset of 3D coordinates (x, y, z), which is submitted to the preprocessing steps based on data filtering, cleaning, registering, and sampling to remove unnecessary noise and prepare for the processing phase, which consists of creating a 3D model, digital terrain model, drawing profiles or applying other numerical solutions. The primary expectations consisted not only of determining the digital model but especially of defining changes in the track geometric parameters over time, caused by operational and climatic loads. While one-time diagnostics provides the current railway track condition, deformation analysis requires comparing data from multiple measurements over various time cycles. This fact remains a challenge for processing laser-scanning data, as comparing at least two clouds of data obtained under different conditions and time periods requires a specific approach. If the digital model (DRM) is the preferred output of laser scanning, we can compare the corresponding model elements or complete the 3D model by using the relevant software tools. Another option for addressing deformations in point clouds is to use graphical-analytical tools to compare data arranged in longitudinal and transverse profiles of the appropriate model. The paper study focuses on solving point cloud deformations via numerical techniques based on data segmentation, feature extraction, and measurement. This technique requires creating a numerical algorithm to compare identical parts of the railway structure, obtained at different times, to detect changes in the geometrical parameters. Unlike the classical deformation analysis, which is based on comparing identical discrete points, the point cloud solution requires more extensive and more precise preparation of raw data to meet accuracy and reliability requirements. The paper describes the diagnosed sections of Tatra Electric Railway, and the comprehensive diagnostics process conducted using a mobile lidar system, terrestrial laser scanning, geodetic monitoring, and a point cloud solution that incorporates numerical functions.

2. History and Characteristics of Tatra Electric Railway

The Tatra Electric Railway (TER) connects tourist centres in the High Tatras mountain resort in northern Slovakia. The High Tatras are a highly popular destination for both winter and summer tourism in Central Europe. Tourism began to develop here, thanks to the construction of railway lines in Slovakia in the mid-19th century. First, the mountain cogwheel railway began operating; later, other forms of transport, such as horse-drawn carriages, omnibuses, and trolleybuses, were introduced. The Tatra Electric Railway commenced construction in 1906, and by 1909, the entire Tatra railway network was operational. The development of tourism has also led to the construction of tourist centres, hotels, mountain huts, and sports facilities. Consequently, in addition to passenger wagons, freight wagons began operating to transport coal, bricks, cement, and other needed cargo. This single-track, narrow-gauge, electrified railway line is further connected by a high mountain cable car and lifts [

1]. Currently, TER is part of the national railway network, managed by Slovak Railways, the authority responsible for national railway infrastructure. The Railway Company provides passenger services, and railway freight transport is controlled by the private company Cargo Slovakia. The entire Tatra Electric Railway is 35.060 km long, with a maximum elevation of about 650 m, and connects all the tourist destinations in the High Tatras. The nominal track gauge is 1000 mm. The railway top is based on a classical construction with a track grid, consisting of rails mounted on rib bases, set on wooden sleepers, and running on a gravel track bed. The design railway speed is approximately 50-60 km/h.

3. Materials and Methods of Comprehensive Diagnostics

The diagnostics of Tatra Electric Railway were divided into three railway sections, which varied in terms of constructional and geometric parameters, as listed in

Table 1. These sections lie along the railway's height and directional curves, featuring various radii and planned traffic speeds. The total length of the experimental locality was approximately 1.5 km. Section No. 1 is situated over the bridge, near the railway station. The section is 250 m long, and the suggested traffic speed is 50 km/h. Its height difference in the longitudinal direction is 5.02 m. Section No. 2 is the longest, measuring 700 m, with a directional curve radius of 300 m and a designed traffic speed of 60 km/h. The longitudinal height difference of this section is about 19.70 m. Section No. 3 has an equal directional curve radius and designed speed as the second section, but the whole longitudinal elevation of the section is about -3.15 m.

The comprehensive diagnostics were conducted by the Department of Railway Construction and Track Management and the Department of Geodesy at the University of Žilina, at the initiative of Slovak Railways. The diagnostics process involved applying several technologies with different physical principles. The overall track condition was determined by continuous measurement of the track's relative geometric position with a mobile system, KRAB

TM–Light (Krab), which can identify the character and magnitude of directional and longitudinal track displacements by defining longitudinal changes in the track grid and rail strips. This measuring vehicle (

Figure 1) provides digital outputs of the complete geometric track parameters, including track gauge measured by a potentiometer, horizontal and vertical track rise, track elevation measured by an inclinometer, track short collapse, and travelled distance obtained by an incremental rotary sensor.

Static loading tests were conducted to assess the deformation resistance of the ground plane and the track ballast at the level of the sleeper bearing surface, every 50 meters along the tested section. At the level of the sleeper bearing surface (ground plane), the tests were carried out at the inner rail strip, rail toe, on the ballast layer, and at the level of the sleeper bearing surface in the track axis. At the same time, the railway body material taken from the subgrade structure was subjected to granulometric analysis in the university geotechnical laboratory. The results of all measurements are presented in the research report [

1] and have been submitted to the responsible personnel of Slovak Railways for assessment of the need for reconstruction by introducing a new type of railway structure.

3.1. Methods of Geodetic Monitoring

Terrestrial laser scanning was the primary method used for geodetic monitoring to determine deformations in the railway line construction caused by operational loads and climatic changes over three years. Laser scanning is a convenient method for railway measurements due to its contactless nature, eliminating the need to enter the operating area. This fact results from the laser scanner principle, which involves sending high-speed light pulses to the object, causing it to reflect and return to the LiDAR sensor. The distance between the scanner and object is measured by determining the elapsed time between the sent and received pulses. Laser scans are taken from multiple positions around a railway line by using a precise terrestrial laser scanner, Leica ScanStation P30, with a defined 3D positional accuracy of 6 mm at 100 m. The raw data were based on the 3D coordinates of each point on the scanned railway object, with an instrument resolution of 1.6 mm per 10 m. In addition to terrestrial laser scanning, the kinematic continuous GNSS method, using a manually operated mobile vehicle, was also applied. The data-acquisition speed was incomparably higher, but accuracy decreased slightly, even with the use of the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), which incorporates an accelerometer and a gyroscope as tilt-compensating sensors for the GNSS antenna. The fast static GNSS method and the spatial polar method were also used to georeference 34 ground control points (GCPs) and 12 railway benchmarks to the European Terrestrial Reference System (ETRS89) using a Leica VIVA SmartStation, achieving positional accuracy of 2 mm and height accuracy of 4–5 mm. Georeferencing involves a least squares adjustment of GCPs, applied in the Burša-Wolf 7-element similarity transformation with Jung's additional post-transformation. The heights of GCPs were determined by a two-way levelling line using a precise digital level (Leica DNA03), with a defined unit standard deviation of 0.3 mm.

3.2. Numerical Solutions of a Point Cloud

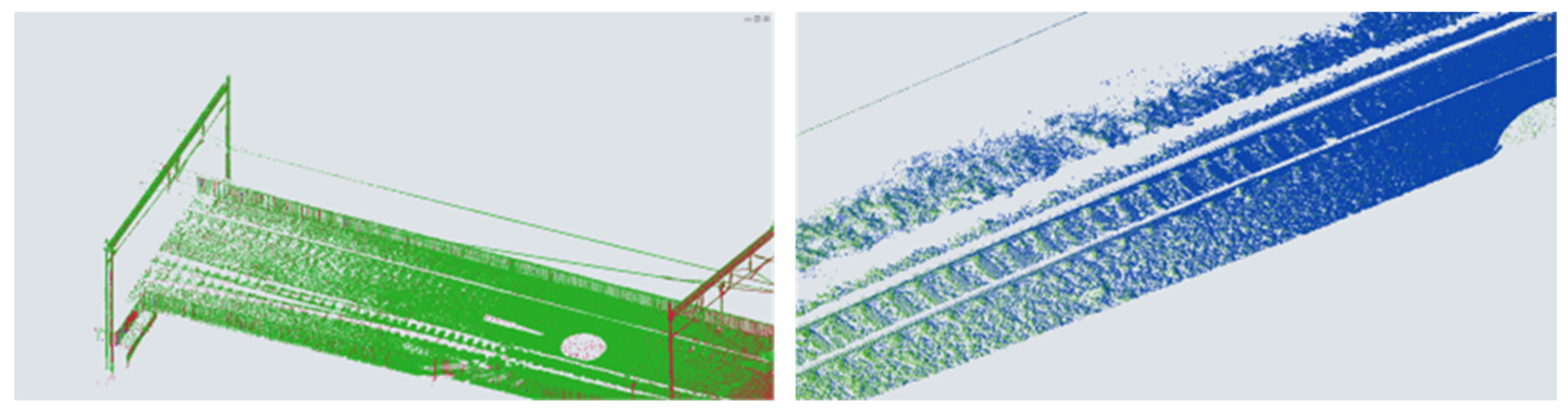

The point cloud solution is the most time-consuming phase, which requires specialised software and hardware with sufficient memory and cloud storage. The processing phase is preceded by a preprocessing that involves preparing raw data (

Figure 2) into a format suitable for the solution and involves: data filtering, which removes points that are either invalid or unnecessary; data sampling, which helps minimise memory requirements and reduce computational requirements in the processing phase; data registration and integration, which involves joining and combining data from multiple sources to create a unified dataset; and data conversion into form appropriate for further solutions and analysis.

A significant portion of the point cloud processing was devoted to identifying identical parts (clusters) of the railway track, which were compared with those acquired in other measurement cycles. A least-squares and robust method was used to estimate the weighted mean of a cluster. Weights were based on the dispersion of data within a cluster. The development of numerical algorithms was inspired by the application of procedures such as clustering, segmentation, and filtering used in professional 3D modelling software. The principle of point cloud segmentation is a well-established method for object recognition, classification, and tracking in 3D modelling, based on deep learning, with wide applications in robotics, autonomous mobile systems, medical diagnostics, construction, transportation infrastructure, farming, crop cultivation, and protection, as well as other industries utilising augmented reality. The IT experts have developed algorithms for point cloud segmentation, each with its own strengths and weaknesses [

2]. These algorithms are part of applications whose primary limitation is the computational complexity of large datasets. They are based on various numerical approaches, which employ filtering procedures derived from statistical methods, differential equations, and other hybrid techniques [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The numerical algorithm was applied to the extracted transverse track profiles, created every 5 metres along the longitudinal track axes. The clustering was performed along the transverse profiles in 2D (x, y) coordinates, and the z-coordinate was set to the median height of the cluster area. The point cloud segmentation was performed by calculating the statistical characteristics of a cluster, which helped define its radius, range, and the distance of internal points from the median. The dispersion of all internal points determined the cluster's weight. Median seems to be a good option because of its sensitivity to data file outliers. The primary condition for comparing data across various measurement cycles was to maintain the positional accuracy of the created transversal profiles and apply the same numerical algorithm to the most precisely defined clusters. The accuracy of the deformation calculation analysis depends significantly on the a priori accuracy of data collection, the accuracy of point cloud registration, and the error propagation during numerical calculations

4. Results and Analysis

The results of the comprehensive diagnostics and geodetic monitoring of the Tatra Electric Railway were submitted to the competent persons of Slovak Railways in the form of a research report [

1], which includes graphical and numerical summaries, an accuracy evaluation, and relevant recommendations. The values obtained by the manual vehicle Krab were processed by KRAB 8.1 software, which generates: numerical and graphical outputs of track geometrical parameters; list of local errors represented the standard deviations determined in the railway sections, which exceed limit values prescribed in technical direction [

9]; sectional and overall quality assessment of the track geometrical parameters, which is given by Track Quality Index (TQI) calculated according to the formula:

where

SDOtg,

SDOtd, SDOte and

SDOle are standard deviations defined as the measures of dispersion of the directional and height parameters obtained every 0,25 along the railway line: track gauge, transversal direction, track transversal elevation, and track longitudinal elevation. An infrastructure manager recommends a method for calculating the TQI that varies by country [

10,

11]. In Slovakia, the values of weighted factors are included in the technical railway direction [

9] as follows:

wtg=0.6,

wtd=0.16,

wte=0.16, and

wle=0.16. The limit values of TQI and other quality indices are also recommended by the direction, which helps reliably evaluate the diagnosed railway line. The standard deviations in formula (1) are the accuracy characteristics calculated according to the well-known formula.

where n is the number of measured values, and

ei are the residuals calculated as the differences from the mean value of the relevant i-th geometrical parameter.

Table 2 presents the quality assessment of three TER railway sections based on the estimated standard deviation of a relevant geometric parameter and the computed TQI (1). This widely used quality index is compared with recommended values based on the railway section's design characteristics (speed, gauge, overall track arrangement).

At the same time as track diagnostics with manual vehicle Krab, the terrestrial laser scanning was performed by using a precise terrestrial laser scanner ScanStation P30 with the ultra-high speed time-of-flight enhanced by Waveform Digitising (WFD) technology and dual-axis compensator, target acquisition 2 mm at 50 m, angular horizontal and vertical accuracy 8 arcseconds and range accuracy 1.2 mm + 10 ppm. The same technology and methodology were used across all three measurement cycles to maintain the homogeneity of the results. The data acquisition and assessment process was carried out in accordance with the technical standard [

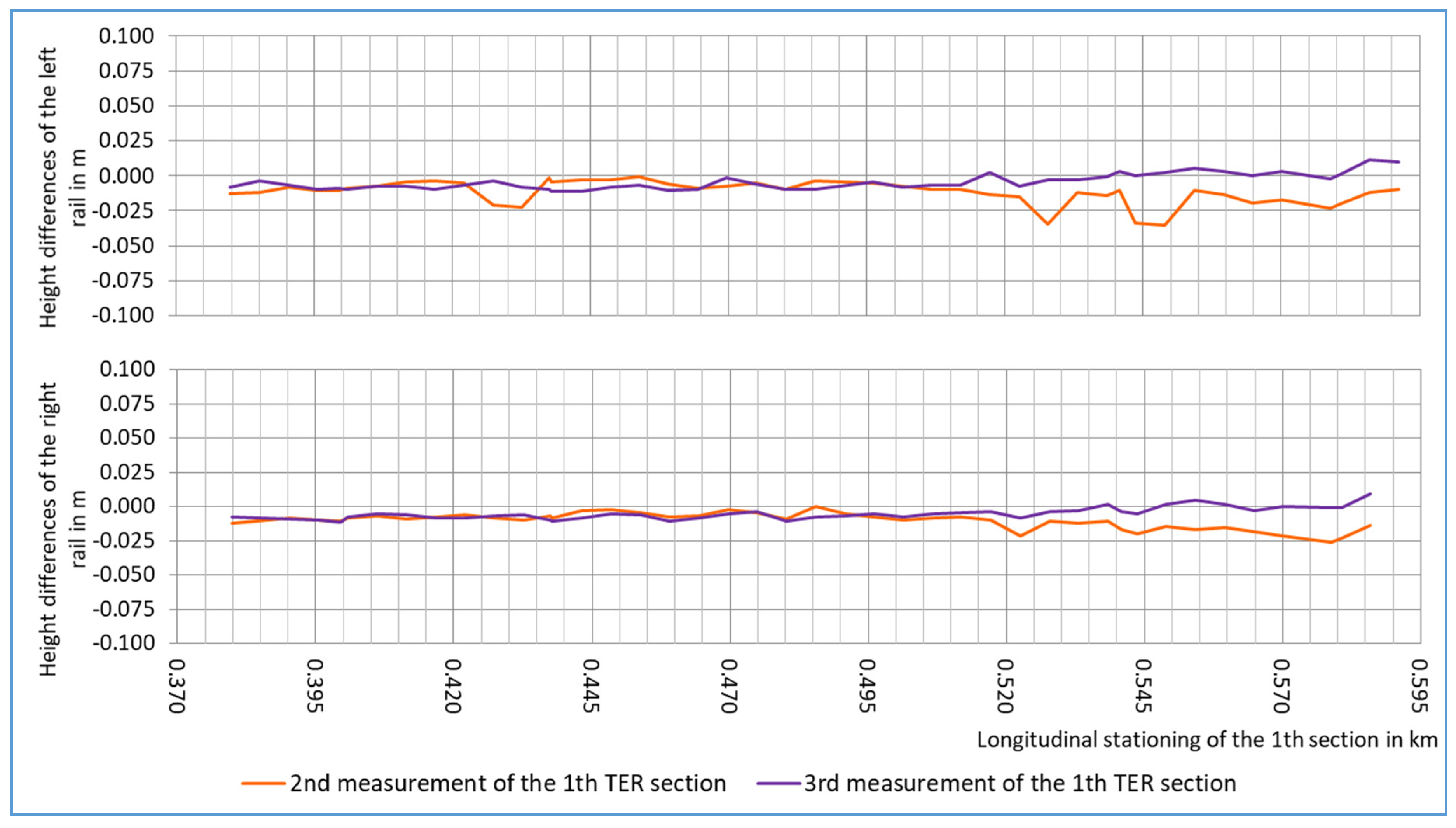

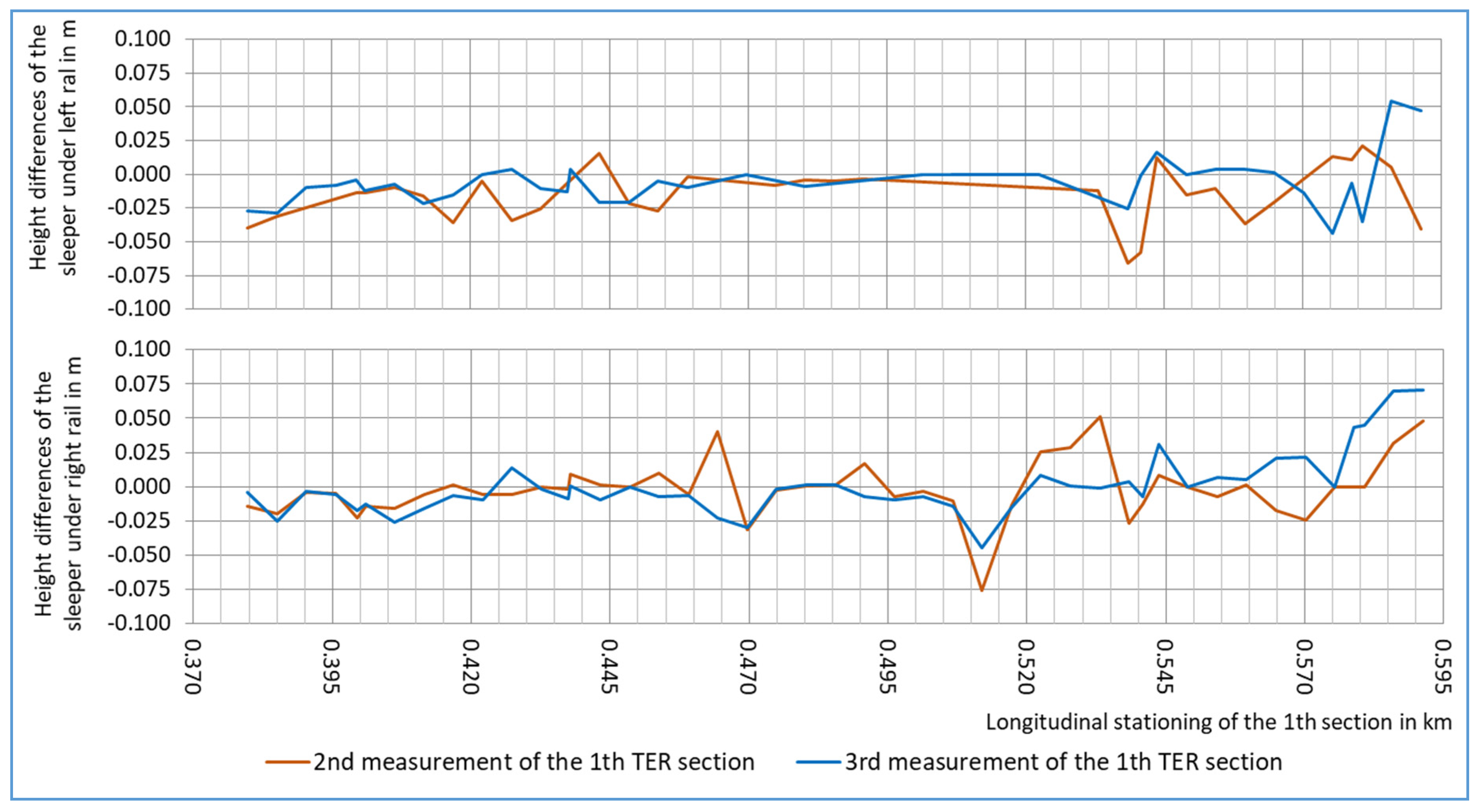

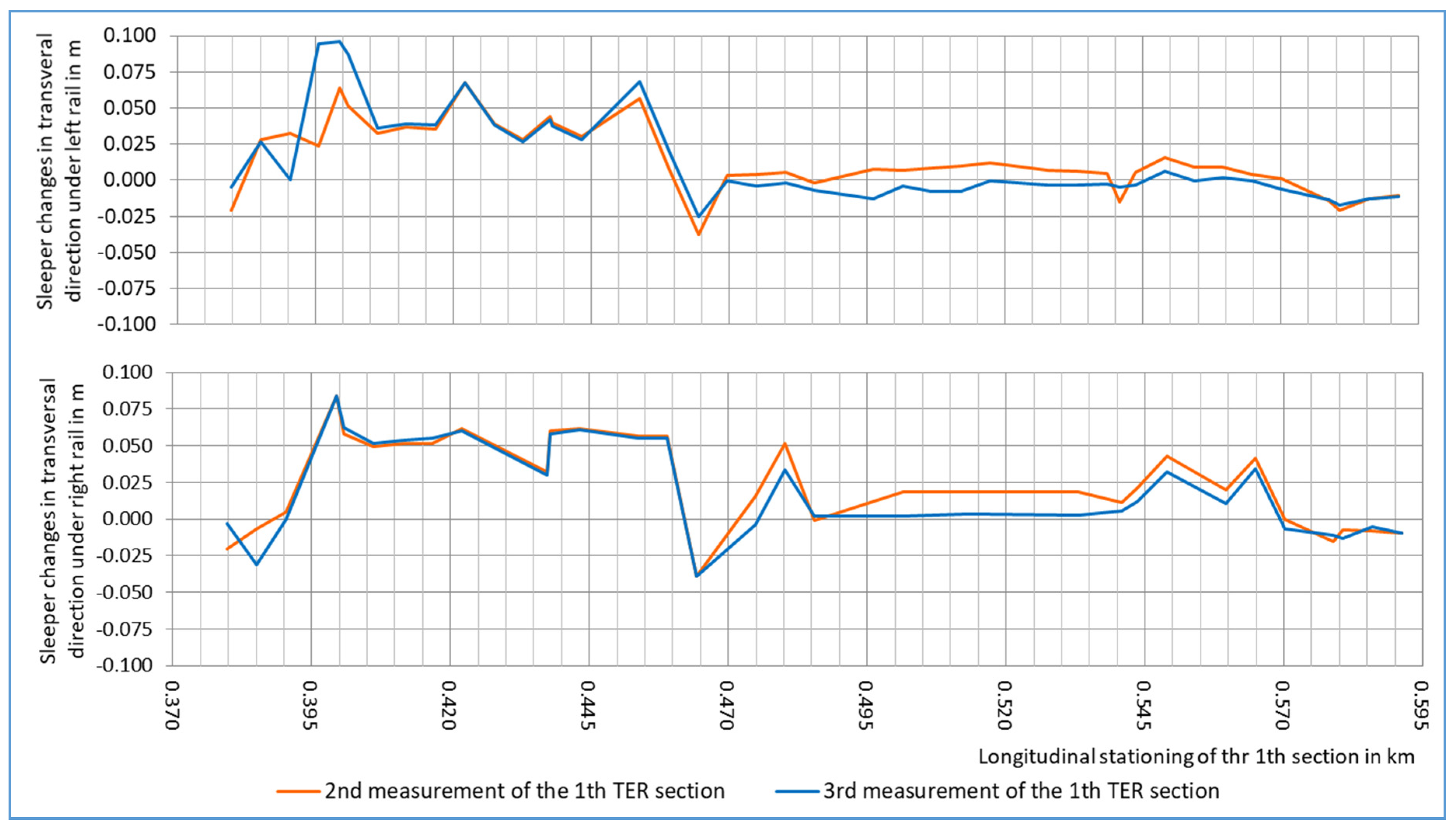

12]. The numerical solution consisted of generating transverse profiles at 0.52 m intervals along the longitudinal track using 3D modelling manipulation functions, such as point cloud filtering, segmentation, and clustering, to compare 3D coordinates within identical clusters across three measurement cycles. The length of the individual transverse profiles was about 0.7 m to the left (-s) and 0.7 m to the right (+s) from the point lying on the longitudinal track axis. The clusters were generated at 0.05 m spacing to retain the expected ambition to determine the spatial track position in the transverse direction precisely. The first scanned section had 45 transversal profiles along the longitudinal axis, 212 m long; the second had 126 transversal profiles, with an overall length of 630 m; and the third section, 511 m long, had 102 transversal profiles. Deformation analysis of the track geometrical parameters scanned in three measurement cycles consisted of: defining height changes separately for the left and right rails; height changes of the sleeper structure at the longitudinal axes and under both rails; horizontal changes of both rails in the transversal direction; changes in the elevation of rails; and changes of track gauge. These changes were computed as the coordinate differences between the corresponding clusters of the i-th (i = 2, 3) measurement cycle and the first measurement cycle. For comparison, the manuscript includes graphical results from

Section 1 on the assessment of height differences for both rails and sleepers under rail and horizontal rail changes, displayed in

Figure 3,

Figure 4, and

Figure 5. The x-axis represents the longitudinal stationing of the appropriate railway section given in km, and the y-axis shows the computed heights or transversal changes in meters. All results of terrestrial laser scanning are included in the research report [

1].

5. Conclusions

Over three years, three measurement cycles of the Tatra Electric Railway were performed to determine construction and geometric track parameters as part of the diagnostics work conducted by the digital mobil system Krab. The results have yielded Track Quality Indices that quantitatively evaluate the current condition of the tested railway line [

10,

11]. It is estimated based on weighted standard deviation propagation computed for each monitored geometrical track parameter [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. These standard deviations and TQI are compared with the recommended values in the technical directions [

9]. In the event of exceeding limit values, the infrastructure manager recommends appropriate maintenance. Terrestrial laser scanning was part of the diagnostics work, with the primary task being to determine spatial track changes in the transverse and longitudinal directions, which were then submitted to deformation analysis. Classical deformation analysis is based on the study of changes of an object discretised by signalised marks. Modern contactless data-acquisition technologies have introduced a new approach to determining deformations by evaluating point clouds or creating 3D models using IT manipulation functions, supported by numerical and statistical techniques. Terrestrial laser scanning corresponds to geodetic methods that acquire large amounts of data and process them using specialised mathematical techniques. The evaluation of three measurement cycles of TER has documented height and directional changes in standard railway construction over three years. According to the accuracy evaluation, all spatial changes greater than 2.6 cm are statistically significant, as they exceed the 95% confidence interval, which corresponds to twice the standard deviation [

13]. Statistical hypothesis testing, as an essential part of deformation analysis [

12,

13], confirms that spatial sleeper changes (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) are significant and require reconstruction. Despite the time-consuming processing phase, laser scanning appears to be an essential part of deformation analysis. The disadvantage of laser scanning in railway applications seems to be its inability to capture the reflective upper part of the rail. This problem is solved by modelling the missing parts of the rail into the desired shape during processing. Terrestrial laser scanning is a contactless geodetic measurement method with excellent results in diagnostics, not only of construction and transport objects, but also of historical buildings, industrial halls, engineering structures, products and other objects and equipment.

Author Contributions

conceptualisation: Jana Izvoltova, Jakub Chromčák, Stanislav Hodas, and Daša Smrčková; methodology: Jana Izvoltova, and Stanislav Hodas; software: Jana Izvoltova; validation: Jana Izvoltova, Jakub Chromčák, and Daša Smrčková; formal analysis: Jana Izvoltova, and Stanislav Hodas; investigation: Jana Izvoltova; resources: Jana Izvoltova, and Stanislav Hodas; data: Jana Izvoltova, Jakub Chromčák, and Daša Smrčková; writing original draft preparation: Jana Izvoltova; writing review and editing: Jana Izvoltova; visualization: Jana Izvoltova, Jakub Chromčák, and Stanislav Hodas; supervision: Jana Izvoltova; project administration: Jana Izvoltova; funding acquisition: Stanislav Hodas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

VEGA - Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences

Acknowledgments

This article is the result of the implementation of the project VEGA 1/0236/25: “Analysis, diagnostics and modification of structural parts in places with a significant change in the stiffness of the railway track“, supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences

References

- Ižvolt L., Šestáková J., Ižvoltová J.: Establishment of contactless track on the Tatra Electric Railway in the inter-station sections of the Poprad-Tatry railway station - Starý Smokovec railway station and the Starý Smokovec railway station - Tatranská Lomnica railway station, University of Žilina, Summary reports of the KŽSTH and KGD, 2018, 2019, University of Žilina in Žilina.

- Honti R., Erdélyi J., Kopáčik: Automation of segmentation of basic geometric primitives from point clouds, Spektrum STU 2024, ISBN 978-80-227-5758-3, 94 p.

- Khan F.: The all-new simplified point cloud processing software. Leica Geosystems 2025, available online: https://leica-geosystems.com/products/laser-scanners/software/leica-cyclone/leica-cyclone-register-360/simplified-point-cloud-processing-software.

- Miao Y., Sun Y., Zhang Y., Wang J., Zhang X.: An efficient point cloud semantic segmentation network with multiscale super-patch transformer. Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 14581, Nature 2024, available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-63451-8. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo F. M., Cabo C., Pardiñas J. R., Loudermilk L. E., Ordóñez C.: 3D Point Cloud Semantic Segmentation Through Functional Data Analysis, Journal of Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Statistics 2024, Springer Nature, Vol. 29, p. 723-744, dostupné online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13253-023-00567-w. [CrossRef]

- Point Cloud Processing. MathWorks 2025, available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/vision/point-cloud-processing.html.

- Rusu R. B.: 3D is here: Point Cloud Library, available online: https://pointclouds.org/assets/pdf/pcl_icra2011.pdf.

- Safri M.: Point Cloud Data — Preparation and Preprocessing, Medium 2024, available online: https://medium.com/@murtazasafri/point-cloud-data-0d8c8208e06f.

- Technical direction SR 103-7 (TS): Measurement and evaluation of geometrical track parameters of track gauge 1435 mm and 1520 mm by measuring vehicle Krab, Slovak Railways 2017, p. 60.

- Offenbacher S., Neuhold J., Veit P., Landgraf M.: Analysing Major Track Quality Indices and Introducing a Universally Applicable TQI, Applied Sciences 10(23):8490, MDPI 2020, p. 16. [CrossRef]

- Unsiwilai S., Phusakulkajorn W., Shen Ch., Zoeteman A., Dollevoet R., Núñez A., Li Z.: Enhanced vertical railway track quality index with dynamic responses from moving trains, Heliyon Vol. 10, Issue 19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Technical Railway Standard TNŽ 736361: Geometrical track position and arrangement of railway lines gauge 1000 mm, Slovak Railways 2007, p. 37.

- Technical Standard STN 73 0275. Accuracy of geometric parameters in construction. Control measurements of linear construction objects. Bratislava 1991.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).