1. Introduction

Urbanisation has emerged as one of the defining demographic, economic, and spatial processes of the 21st century, reshaping settlement patterns and fundamentally altering how cities function and interact with their hinterlands. Across the world, cities are expanding both horizontally through peri-urbanisation and vertically through population densification, producing new spatial forms that transcend their administrative borders. This transformation is reflected in the widening use of concepts such as metropolitan areas, megacity regions, metropolitan regions, and city-regions, all of which attempt to describe the increasingly complex geographies of urbanisation (Tang et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025). Among these constructs, the metropolitan area and metropolitan region have gained particular prominence in urban and transport planning discourse due to their relevance for governance, infrastructure coordination, and regional development strategies.

A metropolitan area is generally understood as a densely built-up zone comprising a core city and its contiguous urbanised surroundings. In contrast, a metropolitan region extends well beyond the physical urban footprint, including satellite towns, emerging economic clusters, peri-urban transition zones, and sometimes even semi-rural settlements that maintain strong functional ties with the metropolitan core (Gori Nocentini, 2025; Nadimi & Goto, 2025). These functional linkages may take the form of daily commuting, supply chain interactions, land-use exchanges, environmental impacts, or administrative dependencies. The distinction between these two units is therefore not merely semantic, but foundational for planning institutions responsible for regional mobility, land management, housing, and environmental systems.

Recent empirical studies emphasise that metropolitan regions function as highly interconnected socio-economic systems rather than discrete urban entities. For instance, spatial evolution assessments of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei and other Chinese city clusters reveal how ecological quality, land-use patterns, and economic activity disperse across entire regions, blurring traditional administrative boundaries (Liu et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2025). Similar patterns are evident in fast-growing metropolitan corridors in Vietnam, India, Europe, and the United States, where urban influence radiates outward from the metropolitan core and drives significant environmental, social, and mobility changes (Liang et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2025). This expanding geography of influence underscores the inadequacy of municipal-scale planning when addressing the realities of metropolitanisation.

The need to distinguish between metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions is particularly acute in the context of transportation planning, as transport infrastructure tends to link labour markets, residential communities, and economic districts across vast regional extents. Research on multimodal and air–rail intermodality in global metropolitan hubs highlights that major transportation systems increasingly operate at a regional scale, shaping accessibility and mobility patterns across entire megaregions (Xiao et al., 2025; Villaruel et al., 2025). This regionalisation of mobility is also evident in the expansion of mass transit corridors, regional expressways, and high-speed rail networks, all of which bind together multiple urban nodes into a functionally unified metropolitan system (van Dijk et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2025).

Parallel to transport dynamics, land-use and environmental changes also reflect metropolitan-scale processes. For instance, studies on ecological and environmental vulnerability in megacities such as Shanghai, Tokyo, Delhi, and São Paulo reveal that pollution transport, microclimatic variation, and ecological degradation do not conform to municipal boundaries but instead propagate across wider metropolitan environments (Salcedo-Bosch et al., 2025; Wu et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Similarly, investigations into urban heat island effects, carbon emission efficiency, and urban resilience demonstrate that regional drivers-including land fragmentation, economic specialisation, and regional policy integration-significantly shape metropolitan ecological conditions (Soltani et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2025). These findings underline the importance of adopting regional frameworks-rather than city-scale approaches-when assessing sustainability challenges.

Governance also emerges as a central dimension distinguishing metropolitan areas from metropolitan regions. While metropolitan areas are often managed by one or two municipal bodies, metropolitan regions typically require multi-scalar governance arrangements, involving provincial governments, regional development authorities, and intermunicipal partnerships. Research on climate adaptation governance, resource integration, and multi-sectoral coordination underscores the necessity of robust metropolitan institutions capable of steering regional planning and development (Gori Nocentini, 2025; Nadimi & Goto, 2025; Helmi et al., 2025). Without institutional alignment, metropolitan regions often struggle with overlapping jurisdictions, inadequate service coordination, and fragmented land-use planning-barriers that directly hinder sustainable development.

In the Indian context, these challenges take on added complexity due to rapid population growth, unregulated peri-urban expansion, and uneven regional development. Regions such as the National Capital Region (NCR), Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), and Bengaluru Metropolitan Region (BMR) are characterised by stark socio-spatial inequalities, highly fragmented governance structures, and severe pressure on transportation and environmental systems. Studies on airborne pollution in Delhi, traffic congestion in Mumbai, and water scarcity in Bengaluru highlight the interconnected nature of metropolitan challenges and demonstrate that city-level interventions are insufficient without a coordinated regional strategy (Joshi & Deshkar, 2025; Hasibuan et al., 2025; Calderón-Garcidueñas et al., 2025). The rapid growth of satellite towns such as Gurugram, Noida, Navi Mumbai, and Whitefield further emphasises the transition from single-core metropolitan areas to multi-nodal metropolitan regions in India.

As metropolitan regions continue to expand in complexity, distinctions between metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions become essential for effective planning, modelling, and policy-making. Understanding these differences aids in identifying appropriate spatial units for analysing mobility flows, environmental risks, housing demand, land-use transitions, governance structures, and socio-economic dynamics (Wang et al., 2025; Qi et al., 2025; Oliveira & Távora, 2025). It also guides the development of tailored interventions-such as regional transport integration, growth boundary regulation, ecological zoning, and metropolitan-scale infrastructure planning-that extend beyond the purview of conventional city governments.

Given these evolving dynamics, this paper seeks to expand the conceptual discourse on metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions by analysing their differences and similarities across a comprehensive set of dimensions, including spatial form, functional relations, governance, economic structure, socio-demographic characteristics, transportation linkages, and environmental implications. Drawing upon contemporary empirical evidence from diverse metropolitan environments and anchored in the expanding literature on urban system evolution and regional planning, the objective is to provide a scholarly and practice-relevant framework that enhances conceptual clarity and supports effective metropolitan governance. The insights generated here aim to benefit researchers, urban planners, policy-makers, and institutional actors engaged in shaping the future of metropolitan development in both emerging and advanced economies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Origins and Definitions of Metropolitanism

The concept of metropolitanism has deep historical and intellectual roots, tracing back to early human settlements that evolved into centres of political, economic, and cultural authority. The term metropolis derives from the Greek word mētēr (mother) and polis (city), literally meaning “mother city,” used in ancient times to denote a dominant urban settlement exercising control over dependent territories or colonies (Mumford, 1938). Classical geographers and historians, including Strabo and Herodotus, described metropolitan centres as hubs of commerce, administration, and cultural exchange, foreshadowing the modern understanding of metropolitan regions as spatially interconnected urban systems.

In modern urban studies, metropolitanism emerged as a distinct theoretical construct alongside rapid industrialisation and transportation revolutions of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Railways, tramways, and later the automobile enabled cities to expand beyond their traditional cores, creating new patterns of commuting, suburbanisation, and functional interdependence. Sir Peter Hall (2004) notes that industrial concentration in city centres, coupled with the rise of mass transit, catalysed the formation of extensive metropolitan regions where economic activity and population growth spilled over well beyond municipal boundaries.

Early sociological and ecological theorists provided foundational interpretations of metropolitan structure. Ernest W. Burgess’s (1925) Concentric Zone Model, part of the Chicago School’s urban ecology, conceptualised the metropolis as a series of socio-spatial rings radiating outward from a dominant core. This model emphasised processes of invasion, succession, and land-use sorting as defining features of metropolitan spatial organisation. Burgess’s ideas were further built upon by scholars such as Homer Hoyt (1939), who proposed the Sector Model, and Harris and Ullman (1945), who articulated the Multiple Nuclei Model. These classic models collectively highlighted how metropolitan growth was shaped by land values, transportation corridors, and economic specialisation.

From the 1950s onwards, the work of Brian Berry and other quantitative geographers reframed metropolitanism within a spatial–economic analytical tradition. Berry (1960s–1970s) identified metropolitan areas as functionally integrated labour markets in which the central city and suburbs were tied together through daily commuting flows, shared service economies, and interlinked land-use systems. Metropolitan regions were no longer defined solely by physical contiguity but by functional relationships-particularly those involving employment, mobility, and residential patterns.

The emergence of metropolitan planning in the late 20th century further expanded the definitional scope of metropolitanism. Scholars such as Gottmann (1961) introduced the idea of “megalopolis”-a vast, continuous urbanised corridor-as a new form of metropolitan expansion driven by economic agglomeration and advanced transport technologies. Contemporary definitions of metropolitanism thus incorporate multi-use intensification, polycentricity, regional governance, and complex mobility networks, recognising that modern metropolitan regions function as dynamic ecosystems of human activity, economic flows, and spatial connectivity.

In sum, metropolitanism has evolved from its classical origins as a “mother city” to a sophisticated concept capturing the socio-spatial dynamics of modern urban regions. The intellectual contributions of Burgess, Hall, Berry, Mumford, and others provide a foundational understanding of metropolitan structure, offering vital theoretical grounding for analysing contemporary challenges of mobility, land-use diversity, regional inequality, and sustainable planning..

2.2. Metropolitan Area in Planning Literature

The concept of a metropolitan area occupies a central place in planning literature, reflecting the complex spatial, economic, and social interactions that extend beyond the boundaries of a single city. In most scholarly and policy definitions, a metropolitan area consists of a primary urban centre and the surrounding urbanised or built-up territories that are functionally integrated with it. This functional integration is commonly manifested through shared labour markets, commuting patterns, service linkages, and socio-economic interdependencies. As urban growth processes have become more diffuse, non-linear, and multi-nodal, the metropolitan area has emerged as a key unit of analysis for understanding contemporary urbanisation.

International agencies such as the United Nations (UN), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Eurostat, and various national statistical offices adopt comparable criteria for defining metropolitan regions. These criteria typically combine population size, density thresholds, contiguity of built-up area, and labour market integration, particularly through commuting flows. For example, the UN’s approach to defining “urban agglomerations” emphasises the continuity of the built environment, whereas the OECD focuses on Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) delineated by travel-to-work zones. These definitions underscore a fundamental recognition in planning literature: that metropolitan regions must be understood not only in morphological terms (physical spread) but also through functional linkages (daily movements, economic transactions, and service networks).

Theoretical literature offers further depth to these understandings. Early urban theorists such as Mumford (1938) and Gottmann (1961) argued that modern metropolitan regions form when economic concentration, transport innovations, and spatial expansion converge to create interdependent urban clusters. This was expanded in the late 20th century through regional science approaches, particularly by scholars such as Vance, Richardson, and Hall, who highlighted the polycentric nature of emerging metropolitan regions. Polycentricity refers to the existence of multiple sub-centres or nodes-commercial hubs, employment districts, or residential clusters-linked by strong transport corridors and economic complementarities.

Commuting patterns remain one of the most widely accepted indicators of metropolitan integration in planning literature. As travel behaviour researchers have demonstrated, daily flows of workers, students, and service seekers form the "metropolitan field" that binds central cities and suburbs into a unified socio-economic system. Hence, metropolitan boundaries are often drawn where a certain percentage of residents commute to the main urban centre or to interconnected secondary centres. This functional definition distinguishes a metropolitan area from smaller urban regions or isolated settlements.

Planning literature also highlights the dynamic and evolving nature of metropolitan regions. Processes such as suburbanisation, peri-urbanisation, sprawl, counter-urbanisation, and re-urbanisation continually reshuffle the morphological form and functional structure of metropolitan areas. As a result, metropolitan boundaries are fluid and often require periodic revision to reflect socio-spatial changes. This is evident in the way Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), Delhi NCR, and New York Metro Region have expanded to include previously rural areas whose economic and commuting ties now fall within metropolitan thresholds.

In contemporary planning debates, the metropolitan area is increasingly seen as the most appropriate scale for addressing issues such as mobility planning, environmental management, housing supply, economic competitiveness, and governance coordination. Its conceptualisation therefore occupies a vital niche in urban studies, serving as a bridge between theoretical perspectives and practical planning interventions.

2.3. Metropolitan Region in Planning Literature

The concept of the metropolitan region has evolved significantly within planning literature, reflecting the widening spatial, economic, and functional footprint of contemporary urbanisation. Unlike the metropolitan area-which typically denotes a contiguous built-up zone surrounding a dominant city-the metropolitan region represents a much broader, multi-scalar spatial entity that integrates urban, peri-urban, and semi-rural territories into a coherent functional system. Planning scholars consistently highlight four defining characteristics of metropolitan regions: (i) their extensive economic influence over an enlarged hinterland; (ii) their multi-nodal urban structure; (iii) the presence of regional transportation corridors, logistics clusters, and industrial networks; and (iv) their capacity to incorporate peri-urban and rural zones into the metropolitan labour, housing, and mobility systems (Gori Nocentini, 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025).

Historically, early conceptual foundations can be traced to Patrick Geddes, whose seminal text Cities in Evolution (1915) laid out the idea of the city-region as a socio-spatial territory shaped not by administrative boundaries but by the flows of labour, capital, information, and ecological processes. Geddes argued that cities must be understood as parts of larger regional organisms, anticipating contemporary understandings of functional urban areas. This perspective strongly influenced later regional planning frameworks in the United Kingdom, United States, and India, promoting the idea that metropolitan governance must recognise the economic and environmental interdependence between urban cores and their hinterlands.

Contemporary scholarship builds upon this foundation, using empirical evidence to demonstrate how metropolitan regions function as interlinked socio-economic systems that extend far beyond traditional municipal limits. For instance, studies of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei and Yangtze River Delta regions reveal a complex geography of spatial flows and ecological interactions that shape regional environmental quality, mobility patterns, and economic specialisations (Liu et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Research on Tokyo’s energy and transportation systems similarly emphasises how metropolitan-scale processes-ranging from electricity grid integration to regional commuting-operate at scales much larger than metropolitan areas (Nadimi & Goto, 2025). This growing body of evidence underscores that metropolitan regions function as nodal networks rather than single-centred entities.

The planning literature also recognises metropolitan regions as the appropriate scale for analysing infrastructure systems, especially transport networks. Regional corridors such as expressways, commuter rail systems, and logistics routes shape the spatial structure of entire regions, influencing where people live, work, and access services (van Dijk et al., 2025; Villaruel et al., 2025). Air–rail intermodality studies show that metropolitan airport regions often extend across multiple municipalities and economic zones, reinforcing the notion that mobility systems operate at regional, not municipal, scales (Xiao et al., 2025). These insights have profound implications for transport planning, as infrastructure investment and accessibility modelling increasingly require metropolitan-regional approaches.

Environmental research further strengthens the metropolitan region concept. Pollution dispersion, urban heat island effects, and ecological degradation often do not respect administrative boundaries; instead, they propagate across regional landscapes, linking multiple urban centres into shared environmental systems (Wu et al., 2025; Soltani et al., 2025; Calderón-Garcidueñas et al., 2025). Consequently, sustainable development strategies now favour regional ecological zoning, multi-jurisdictional watershed management, and region-wide resilience planning.

Governance literature adds another critical dimension: metropolitan regions require multi-level coordination mechanisms involving regional development authorities, provincial governments, municipal bodies, and specialised agencies. The complexity of regional economic networks, housing markets, and ecological systems demands integrated strategies that go beyond the mandates of individual cities (Gori Nocentini, 2025; Helmi et al., 2025). Without such coordination, metropolitan regions tend to face fragmented planning, uneven development, and inefficient service delivery.

In summary, planning literature positions the metropolitan region as a comprehensive spatial, economic, and ecological unit that better reflects the realities of contemporary urbanisation. It acknowledges the need for regional-scale frameworks to understand mobility, environmental challenges, governance structures, and economic development, building upon a century of conceptual evolution from Geddes’ city-region to modern metropolitan-regional planning.

2.4. Comparative Studies

Comparative research across global metropolitan systems has consistently shown that distinguishing between the administrative definition of metropolitan areas and the functional delineation of metropolitan regions is essential for effective spatial planning, infrastructure development, and governance. International studies conducted under frameworks such as ESPON, the EU Urban Agenda, and OECD metropolitan typologies emphasise that administrative boundaries rarely capture the true socio-economic footprint of metropolitanisation. Instead, metropolitan regions often extend beyond statutory jurisdictions, forming complex networks of settlements, economic clusters, and mobility corridors. European evidence shows that metropolitan regions-such as the Randstad, the Rhine-Ruhr, and Greater London–South East-function as polycentric territorial systems characterised by interdependent labour markets, multi-nodal transport connectivity, and shared ecological systems. Similar observations are echoed in environmental and regional analyses that use spatial interaction modelling and ecological assessments to map regional-scale processes across metropolitan Europe (Čudlin et al., 2025; Calderón-Garcidueñas et al., 2025).

Table 1.

Comparative Characteristics of Metropolitan Areas vs Metropolitan Regions Across Global Contexts.

Table 1.

Comparative Characteristics of Metropolitan Areas vs Metropolitan Regions Across Global Contexts.

| Region / Framework |

Administrative Metropolitan Area |

Functional Metropolitan Region |

Key Planning Observations |

Supporting Evidence (from your citations) |

| Europe (ESPON, EU Urban Agenda) |

Usually reflects built-up contiguous urban zones around a core city (e.g., Paris Métropole, Amsterdam). |

Multi-city, polycentric regions such as Randstad, Rhine-Ruhr, Greater London–South East. Includes satellite cities, logistics hubs, cross-boundary labour markets. |

Strong emphasis on polycentricity, regional accessibility, multi-level governance, transport corridors, and integrated environmental systems. |

Čudlin et al. (2025); Calderón-Garcidueñas et al. (2025) |

| Tokyo Megaregion (East Asia) |

Tokyo 23 Wards + immediate suburban municipalities within the contiguous urban fabric. |

Greater Tokyo Megaregion spanning Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba, Kanagawa. Unified by extensive commuter rail networks, metropolitan expressways, and integrated energy grids. |

Highly networked, transit-driven megaregion; functional area extends far beyond administrative boundaries; one of the world’s largest labour markets. |

Nadimi & Goto (2025); Xiao et al. (2025) |

| Shanghai–Yangtze River Delta (East Asia) |

Shanghai municipality and immediate peri-urban built-up zones. |

Regional system including Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang; interconnected economic zones, industrial belts, and regional ecological systems. |

Demonstrates strong inter-city economic flows, pollution dispersion across regional scales, and integrated industrial corridors. |

Zhang et al. (2025); Wu et al. (2025); Liang et al. (2025) |

| Delhi Metropolitan Area (India) |

Delhi NCT and contiguous urbanised areas within its municipal limits. |

National Capital Region (NCR) spanning 4 states, including Gurugram, Noida, Faridabad, Ghaziabad, Meerut. |

Marked mismatch between administrative and functional boundaries; commuting patterns and land markets operate at regional scale. |

Hensel et al. (2025); Joshi & Deshkar (2025) |

| Mumbai Metropolitan Area (India) |

Greater Mumbai + continuous built-up areas (e.g., Mumbai, Thane). |

Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR): Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, Thane, Kalyan-Dombivli, Vasai-Virar, and growth centres. |

Polycentric expansion, extensive commuting flows, and significant environmental spillovers across coastal and inland regions. |

Calderón-Garcidueñas et al. (2025); Fang et al. (2025) |

| Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (India) |

BBMP jurisdiction and immediate built-up extensions. |

Bengaluru Metropolitan Region (BMR): Includes Anekal, Nelamangala, Hoskote, Devanahalli and adjoining growth nodes. |

Rapid peri-urbanisation; metropolitan expansion driven by IT corridors and unplanned sprawl beyond municipal boundaries. |

Liu et al. (2025); Oliveira & Távora (2025) |

| General Global Patterns |

Defined primarily by administrative or morphological criteria: built-up continuity, population thresholds. |

Defined by functional criteria: labour markets, commuting flows, economic linkages, ecological systems, transport networks. |

Metropolitan regions consistently demonstrate wider functional territory than metropolitan areas, creating governance and planning challenges. |

|

In East Asia, the distinction between metropolitan area and metropolitan region is even more pronounced due to the scale and speed of urban expansion. The Tokyo Megaregion, covering parts of Tokyo, Saitama, Kanagawa and Chiba, functions as an integrated economic and transport system well beyond the municipal boundaries of Tokyo Metropolis. Studies reveal that infrastructure systems-particularly energy grids, commuter rail lines, and expressway networks-operate at the megaregional scale rather than the city scale, highlighting the limitations of traditional metropolitan boundaries (Nadimi & Goto, 2025; Xiao et al., 2025). Similarly, research on the Shanghai–Yangtze River Delta Region, which includes Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, demonstrates that industrial development, air quality patterns, and ecological interactions extend across a vast, interconnected region (Zhang et al., 2025; Wu et al., 2025). Land-use transformation studies reinforce this view, illustrating how peri-urban growth and polycentric sub-centres have reconfigured spatial structures in ways that cannot be captured by city-level planning instruments (Liang et al., 2025; Lin et al., 2025). These findings underscore the emergent megaregional character of East Asian urbanisation.

In India, comparative metropolitan research highlights systemic challenges in governance, planning integration, and boundary demarcation. The National Capital Region (NCR), governed by the NCR Planning Board (NCRPB), encompasses Delhi and parts of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan-demonstrating the functional reach of the Delhi metropolitan region far beyond the Delhi Metropolitan Area. Similar patterns characterise the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) administered by the MMRDA, which integrates Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, Thane, Kalyan–Dombivli, and several growth centres. Likewise, the Bengaluru Metropolitan Region (BMR) includes multiple taluks outside the municipal limits of Bengaluru, forming a broader labour and housing market. Studies on traffic modelling, environmental vulnerability, water demand, and land-use transitions in Indian metropolitan regions reveal substantial spatial mismatches between administrative metropolitan boundaries and functional metropolitan processes (Hensel et al., 2025; Joshi & Deshkar, 2025; Liu et al., 2025). Research on peri-urban expansion and land governance in Asian cities further confirms that metropolitan regions in India are undergoing polycentric transformation similar to their East Asian counterparts (Oliveira & Távora, 2025; Fang et al., 2025).

Overall, comparative studies across Europe, East Asia, and India converge on a central theme: metropolitan regions represent the true functional scale of contemporary urbanisation, whereas metropolitan areas represent a narrower administrative or morphological subset. Recognising this distinction is crucial for integrating transportation planning, environmental management, regional governance, and sustainable development strategies.

2.5. Gaps in Literature

Although existing literature provides conceptual definitions and regional case studies, comprehensive comparative analyses distinguishing metropolitan areas from metropolitan regions remain limited, particularly in developing countries. Most studies address these concepts independently, focusing either on urban form or regional functional linkages, without systematically examining their differences across spatial, governance, economic, environmental, and transport dimensions. Empirical evidence from rapidly urbanising contexts such as India, Southeast Asia, and parts of Africa is especially scarce. This paper addresses this gap by offering a structured, multi-dimensional comparison that integrates global theoretical insights with emerging metropolitan development patterns in developing country contexts.

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Metropolitan Area: A Compact Urban Fabric

A metropolitan area represents:

1. A primary city,

2. Surrounding suburbs and satellite neighbourhoods,

3. A contiguous built-up environment.

It is fundamentally a localised urban system characterised by:

Urban density,

• Continuous infrastructure,

• Daily commuting zones,

• Institutional governance by urban local bodies.

The metropolitan area represents the most widely recognised spatial unit in urban and regional planning. Conceptually, it is defined as a compact, contiguous built-up zone comprising a primary urban core and its immediately surrounding suburbs, satellite neighbourhoods, and peri-urban extensions that maintain strong physical and functional continuity with the core city. Unlike broader regional constructs, the metropolitan area is characterised by spatial cohesion, morphological unity, and a high degree of infrastructural integration, making it the fundamental scale at which most urban services, municipal functions, and local development activities are planned and delivered.

Figure 1.

Metropolitan Conceptual Framework.

Figure 1.

Metropolitan Conceptual Framework.

At its core, a metropolitan area consists of three essential components: (i) the primary city, which acts as the central node of governance, employment, services, and cultural functions; (ii) adjacent suburbs and secondary neighbourhoods whose growth is closely tied to the expansion of the core city; and (iii) a contiguous built-up fabric that ensures physical continuity across the entire urban footprint. This continuity differentiates metropolitan areas from metropolitan regions, as the latter encompass discontinuous settlement clusters and multiple urban nodes.

Functionally, metropolitan areas are defined by high urban density, reflecting intensive land-use concentration, vertical development, and compact settlement patterns. This density supports a broad range of urban amenities and economic activities while enabling efficient land consumption and infrastructure delivery. The presence of continuous infrastructure-including roads, public transit networks, water supply systems, and waste management facilities-reinforces the integrated nature of the metropolitan area, ensuring seamless mobility and service provision within its boundaries.

Another central feature is the daily commuting zone, often referred to as the functional urban area (FUA) in European planning practice. Commuting patterns within metropolitan areas typically revolve around the primary city as the employment hub, with suburban populations engaging in regular flows toward the core. These flows create identifiable labour market zones and travel-to-work areas that underpin socio-economic cohesion within the metropolitan area.

Governance within metropolitan areas is generally anchored in urban local bodies, such as municipal corporations, city councils, or metropolitan municipalities. These institutions regulate land use, provide essential services, manage transport systems, and oversee urban development according to local planning frameworks. While governance fragmentation may exist in multi-jurisdictional metropolitan areas, administrative coordination is still relatively manageable compared to that of metropolitan regions, where governance often spans multiple municipal and regional governments.

In summary, the metropolitan area embodies a compact, cohesive, and infrastructure-integrated urban system that forms the immediate urban environment of a city. Its spatial unity and functional coherence make it fundamental to understanding localised urban dynamics and distinguishing them from broader regional processes.

3.2. Metropolitan Region: A Broad, Multi-Nodal Territorial System

A metropolitan region encompasses:

1. The metropolitan area,

2. Nearby towns, satellite cities, and growth centres,

3. Rural hinterlands that are economically connected to the city.

A metropolitan region represents a significantly broader spatial construct than the metropolitan area, encompassing a diverse set of urban, semi-urban, and rural territories that together form an extended functional system. While the metropolitan area captures the compact and contiguous urban fabric anchored around a primary city, the metropolitan region incorporates multiple settlement types and economic nodes that interact intensively with the metropolitan core. As such, it reflects the true geographical extent of contemporary urbanisation, where socio-economic, environmental, and mobility processes transcend municipal or morphological boundaries.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework for Metropolitan Region.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework for Metropolitan Region.

At the core of every metropolitan region lies the metropolitan area, which functions as the primary engine of employment, higher-order services, innovation, and institutional capacity. However, what distinguishes a metropolitan region from its compact counterpart is the inclusion of a wider constellation of settlements. These include nearby towns, emergent satellite cities, peri-urban transition zones, logistics corridors, industrial clusters, special economic zones, and growth centres, all of which maintain strong functional linkages with the central metropolitan area. These linkages may be defined by labour market integration, commuting flows, supply-chain networks, shared infrastructure, or socio-environmental interactions.

The metropolitan region also extends into rural hinterlands that are economically or environmentally connected to the metropolitan core. These hinterlands may host agricultural zones supplying food to urban markets, ecological areas providing essential ecosystem services, or villages engaged in metropolitan labour through seasonal or circular migration. In many rapidly urbanising countries, rural settlements around metropolitan regions experience profound transformations, including land-use conversion, demographic shifts, and infrastructure expansion, as they become gradually absorbed into metropolitan economic circuits. This blurring of the urban–rural boundary is a defining feature of modern metropolitan regionalisation.

Another distinguishing attribute of metropolitan regions is their multi-nodal spatial structure. Unlike metropolitan areas-which typically revolve around a single dominant core-metropolitan regions often exhibit polycentric configurations where several urban nodes operate as secondary centres of employment, commerce, education, and housing. These nodes may emerge organically from historic towns or be deliberately planned through policies such as growth centre development, industrial corridor creation, or regional transit investments. The polycentricity of metropolitan regions contributes to spatial rebalancing by distributing growth beyond the primary core and enhancing regional accessibility.

Functionally, metropolitan regions are shaped by large-scale infrastructure networks, especially transportation systems such as expressways, commuter rail services, bus rapid transit, and regional logistics corridors. These systems sustain daily commuting patterns that often span tens or even hundreds of kilometres, linking workers, consumers, and firms across jurisdictions. Similarly, environmental systems-such as watershed areas, green corridors, and airsheds-often operate at regional scales, making metropolitan regions more appropriate than city-level units for environmental management and resilience planning.

Governance within metropolitan regions, however, tends to be highly complex due to the multiplicity of actors and administrative divisions. Unlike metropolitan areas, which are typically governed by one or a few municipal authorities, metropolitan regions involve state or provincial governments, district administrations, regional planning bodies, development authorities, and special-purpose agencies. This governance fragmentation presents challenges related to coordination, resource allocation, infrastructure development, and policy coherence. As a result, metropolitan regional governance often demands formalised coordination mechanisms, intergovernmental partnerships, and shared planning frameworks.

In essence, the metropolitan region is a broad, multi-nodal, functionally integrated territorial system that better captures the true spatial, economic, and ecological footprint of modern urbanisation. It incorporates the metropolitan area while extending into diverse zones that are tied together by flows of people, goods, capital, and environmental processes. Understanding this broader territoriality is essential for addressing regional mobility, balanced development, environmental sustainability, and integrated governance.

It is characterised by:

• Multi-nodal and polycentric spatial structures,

• Non-contiguous development patterns,

• Regional transport flows,

• Industrial and logistics clusters,

• Complex inter-jurisdictional governance.

3.3. Spatial Extent and Boundaries

Metropolitan area boundaries are based on:

• Census-defined urban agglomerations,

• Contiguous built-up areas.

Metropolitan region boundaries are based on:

• Economic corridors,

• Regional commuting patterns,

• Planning jurisdiction (e.g., NCRPB),

• Multi-district or multi-state territories.

Table 2.

Spatial Extent and Boundary Criteria for Metropolitan Area vs Metropolitan Region.

Table 2.

Spatial Extent and Boundary Criteria for Metropolitan Area vs Metropolitan Region.

| Dimension |

Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Region |

| Primary Basis of Delineation |

Census-defined urban agglomerations; municipal limits; statutory city boundaries. |

Functional economic regions; regional planning jurisdictions; multi-district or multi-state administrative zones. |

| Spatial Form |

Compact, contiguous built-up area; high-density urban fabric. |

Discontinuous, polycentric spatial networks; includes towns, satellite cities, and peripheral settlements. |

| Urban Contiguity |

Mandatory contiguous built-up morphology. |

Not dependent on physical contiguity; includes separate nodes connected functionally. |

| Economic Integration |

Local-level labour markets centred on the primary city. |

Regional labour markets, industrial belts, logistics corridors, and multi-city economic systems. |

| Commuting Flows |

Daily commuting within the city and its suburbs. |

Long-distance commuting across districts and sometimes states; regional mobility networks. |

| Administrative Structure |

Governed by one or a few municipal bodies or metropolitan municipalities. |

Multi-jurisdictional governance: state/provincial authorities, development authorities (e.g., NCRPB, MMRDA), district administrations. |

| Boundary Determination |

Primarily statistical (census), morphological, or municipal. |

Determined by planning mandates, mobility patterns, economic corridors, and regional policy frameworks. |

| Examples |

Delhi Urban Agglomeration, Greater Mumbai, Bengaluru Urban District. |

NCR (Delhi), Mumbai Metropolitan Region, Yangtze River Delta, Tokyo Megaregion. |

| Scale and Extent |

Smaller, compact spatial entity. |

Larger territorial span covering diverse settlement types and hinterlands. |

Spatial extent serves as one of the most fundamental distinctions between metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions. Metropolitan areas are typically defined through statistical and morphological criteria, relying heavily on census-defined urban agglomerations and the presence of a contiguous built-up fabric. This makes their boundaries relatively straightforward, emphasising compactness, continuous settlement, and immediate suburban expansion. Because these boundaries are tied to built form, they tend to remain stable over short periods, expanding incrementally as urbanisation progresses outward. Municipal authorities often use these boundaries for service delivery, infrastructure investment, and local development planning.

In contrast, the boundaries of metropolitan regions are determined by functional, economic, and governance logics rather than physical contiguity. Metropolitan regions incorporate economic corridors, regional commuting patterns, multi-district administrative zones, and growth centres, forming a wider socio-spatial system that cannot be captured through morphological criteria alone. Their extent often encompasses entire districts, sometimes multiple states, and diverse settlement types that maintain strong economic or mobility connections with the core city. Planning jurisdictions such as the NCR Planning Board (NCRPB) or the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) delineate metropolitan regions based on broader development mandates, regional transport integration, industrial clustering, and strategic planning objectives.

The distinction becomes especially important in fast-growing economies, where metropolitanisation unfolds through polycentric expansion, commuter belts, and peri-urban transformation. Metropolitan regions evolve well beyond the compact built-up area, reflecting labour market flows, infrastructure networks, ecological systems, and logistics routes that extend across large geographical scales. Their boundaries are fluid, often adjusted to reflect emerging growth nodes, newly urbanising corridors, or expanding economic hinterlands. Recognising these dynamic, multi-scalar geographies is therefore essential for coordinated planning, regional governance, and sustainable metropolitan development.

4. Comparative Analysis: Differences Between Metropolitan Area and Metropolitan Region

This section provides an in-depth, thematic comparison.

4.1. Spatial Scale

Metropolitan Area:

• Smaller spatial extent.

• Compact and city-centric.

• Reflects immediate suburban growth.

Metropolitan Region:

• Much larger spatial spread.

• Encompasses multiple towns and districts.

• Subsumes rural and semi-urban territories.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Spatial Scale.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Spatial Scale.

| Dimension |

Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Region |

| Spatial Extent |

Smaller, compact, contiguous built-up zone around a primary city. |

Much larger territorial span extending across multiple districts, municipalities, and rural hinterlands. |

| Urban Form |

Highly urbanised, continuous city fabric with limited spatial breaks. |

Polycentric or multi-nodal; includes dispersed towns, satellite cities, industrial corridors, and disconnected urban clusters. |

| Growth Pattern |

Reflects immediate suburban expansion of the core city. |

Driven by regional development forces, long-distance commuting, corridor-based growth, and cross-boundary networks. |

| Geographical Components |

City core + adjoining suburbs + inner peri-urban zones. |

City-region + satellite cities + market towns + rural periphery + logistic and economic zones. |

| Boundary Logic |

Determined by census data, built-up contiguity, or municipal boundaries. |

Determined by functional interactions, economic catchments, mobility corridors, and regional planning jurisdictions. |

| Scale of Planning |

Local or municipal. |

Inter-municipal, district-wide, state-level, or multi-state planning. |

| Examples |

Greater Mumbai UA, Delhi Urban Agglomeration, Bengaluru UA. |

Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), Delhi NCR, Yangtze River Delta, Tokyo Megaregion. |

Spatial scale represents the most visible and measurable difference between a metropolitan area and a metropolitan region. A metropolitan area is inherently compact, emerging from the continuous physical expansion of a primary city and its suburbs. The built environment remains largely contiguous, with high-density neighbourhoods, well-integrated public services, and limited spatial gaps. This compactness is the result of incremental suburban growth radiating outward from the core city. Consequently, the metropolitan area reflects a city-centric pattern of development and is often used in urban planning for infrastructure provision, zoning, mobility planning, and population-based service delivery.

In contrast, a metropolitan region covers a substantially broader spatial footprint. It extends beyond the contiguously urbanised fabric to include multiple towns, satellite cities, industrial nodes, economic corridors, and rural hinterlands. The region's configuration is shaped not by physical continuity but by functional linkages-such as labour flows, commuting patterns, inter-city trade, ecological interdependencies, and regional transport networks. Metropolitan regions frequently span multiple districts or even states, as demonstrated by the National Capital Region in India, which integrates Delhi with several adjoining cities across three states. This expansive territorial inclusion reflects economic geographies that transcend administrative barriers and capture the wider influence of metropolitan growth.

The spatial spread of metropolitan regions creates multi-nodal structures, where several urban centres operate as interconnected hubs of employment, commerce, education, and housing. Unlike metropolitan areas, where the primary city dominates spatial organisation, metropolitan regions accommodate diverse growth poles and foster regional rebalancing. These nodes may be geographically separated yet economically integrated, connected through expressways, commuter railways, logistics corridors, and digital infrastructure. The result is a large-scale urban system whose spatial logic is defined by flows rather than proximity.

Ultimately, understanding spatial scale is crucial because metropolitan regions represent the true functional extent of contemporary urbanisation, while metropolitan areas capture only its contiguous morphological footprint. This has major implications for regional governance, transport planning, and sustainable urban development.

4.2. Urban Form

Metropolitan Area:

• Predominantly continuous built-up form.

• Dominated by residential, commercial, and industrial clusters close to the core.

Metropolitan Region:

• Discontinuous, with gaps between urban nodes.

• Polycentric with multiple urban centres (e.g., Gurugram, Noida, Faridabad in NCR).

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis of Urban Form.

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis of Urban Form.

| Dimension |

Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Region |

| Built-Up Pattern |

Predominantly continuous and compact built-up form extending outward from the city core. |

Discontinuous form with spatial gaps between towns, growth centres, and semi-rural settlements. |

| Dominant Land-Use Structure |

Concentration of residential neighbourhoods, commercial districts, and industrial zones clustered near the core city. |

Combination of urban clusters, satellite cities, peri-urban belts, logistics hubs, industrial corridors, and rural areas. |

| Morphological Characteristics |

High-density urban morphology; limited fragmentation; spatial cohesion driven by contiguous built-up areas. |

Polycentric morphology with multiple nodes of varying sizes, each having independent but interconnected economic functions. |

| Growth Dynamics |

Driven by suburbanisation, densification, and immediate expansion into adjacent built-up zones. |

Driven by regional corridors, market towns, new urban extensions, special economic zones, and transportation-led development. |

| Examples |

Central Delhi + South/North/West Delhi suburbs; Greater Mumbai; core Bengaluru. |

Gurugram, Noida, Ghaziabad, Faridabad (NCR); Navi Mumbai, Thane, Kalyan (MMR); Anekal, Devanahalli (BMR). |

Urban form constitutes one of the clearest distinctions between a metropolitan area and a metropolitan region. A metropolitan area is typically defined by a continuous, compact built-up structure, where the city core expands outward gradually into surrounding suburbs and inner peri-urban neighbourhoods. This contiguity results from organic suburbanisation, housing demand, and densification processes. Land-use structure remains heavily concentrated around the primary city, with residential, commercial, and industrial clusters located within a short distance from the core. The result is a cohesive urban fabric with minimal spatial fragmentation and strong infrastructure continuity.

In contrast, the metropolitan region exhibits a far more discontinuous, dispersed, and fragmented urban form. Instead of a single dominant centre surrounded by contiguous built-up areas, metropolitan regions contain multiple spatially separated nodes-cities, towns, logistics parks, industrial estates, and peri-urban settlements-interspersed with agricultural land, ecological areas, or semi-rural zones. This polycentric structure is evident in regions such as the National Capital Region (NCR), where Gurugram, Noida, Faridabad, and Ghaziabad operate as major urban centres independent of, yet economically integrated with, the Delhi core. Such polycentricity arises from rapid urbanisation, transportation infrastructure expansion, deliberate growth-centre planning, and the emergence of new economic corridors.

Metropolitan regional form is thus shaped not by morphological adjacency but by functional interdependence. Discontinuous nodes remain connected through highways, commuter rail systems, digital networks, and labour market flows, creating a unified regional system despite physical separation. This complex and multi-nodal morphology reflects broader urbanisation processes occurring at regional and national scales, where growth increasingly favours decentralised urban centres over traditional monocentric expansion. Understanding these differences in urban form is crucial for planning land use, mobility systems, environmental management, and regional governance structures.

4.3. Integrated Comparative Analysis: Functional, Governance, Economic, Mobility, Environmental, and Social Dimensions

Table 5.

Integrated Comparative Analysis of Metropolitan Area vs Metropolitan Region.

Table 5.

Integrated Comparative Analysis of Metropolitan Area vs Metropolitan Region.

| Dimension |

Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Region |

| Functional Linkages |

Dominated by daily commuting to the central city; short-distance mobility; concentration of high-level consumer services within the core. |

Complex regional flows of goods, labour, capital, and information; inter-city commuting patterns; extensive regional economic and functional networks. |

| Governance Structure |

Managed by municipal corporations, local development authorities, or unified city agencies; governance relatively contained. |

Multi-jurisdictional governance involving multiple municipalities, districts, and sometimes states; often overseen by regional development authorities (e.g., NCRPB, MMRDA). |

| Economic Structure |

Service-sector dominated economy; concentration of office districts, retail hubs, and core business services. |

Highly diversified economy including industrial corridors, logistics hubs, agricultural hinterlands, IT parks, and satellite business districts. |

| Transportation & Mobility |

Intra-city transit systems such as metro networks, city buses, para-transit, and neighbourhood last-mile services. |

Regional transportation systems such as suburban rail, RRTS, expressways, inter-city bus services, multi-modal freight corridors, and integrated logistics networks. |

| Environmental Characteristics |

Urban heat islands, localised air pollution, traffic congestion, stormwater stress due to urban density. |

Regional ecological pressures including watershed degradation, rural–urban ecological conflicts, peri-urban agricultural land loss, and pollution dispersion across wider territories. |

| Social & Demographic Characteristics |

High population density; socio-economic diversity concentrated around the urban core; higher share of intra-city migrants. |

Mixed urban, peri-urban, and rural population; demographic variations across towns and districts; differing income patterns across the regional system. |

The functional characteristics of metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions reveal distinct but interlinked urban systems. Metropolitan areas are primarily characterised by short-distance commuting, centralised consumption patterns, and a strong economic pull of the core city. Daily mobility flows converge toward the central business district, reinforcing monocentricity and localised service-sector concentration. In contrast, metropolitan regions operate on a broader spectrum of functional linkages, incorporating inter-city labour mobility, regional supply chains, and multi-directional flows of goods, capital, and information. These systems embody complex economic interdependencies supported by emerging corridors, satellite cities, and decentralised employment hubs.

Governance structures further differentiate these spatial units. While metropolitan areas are generally governed by municipal corporations or city-level agencies, metropolitan regions demand coordinated governance across jurisdictions, often involving multiple municipal bodies, district administrations, and state-level institutions. Regional planning authorities such as the NCR Planning Board (NCRPB) and the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) exemplify the need for specialised institutional mechanisms to manage cross-boundary development, regional mobility integration, and large-scale infrastructure provisioning.

Economically, metropolitan areas maintain a strong orientation toward service-sector activities, with dense clusters of offices, retail spaces, and urban services concentrated near the core. Meanwhile, metropolitan regions accommodate a diversified economic landscape, spanning industrial corridors, logistics hubs, IT parks, agricultural zones, and new urban extensions. This diversification enhances regional resilience and supports balanced growth across multiple nodes.

Distinct mobility patterns also emerge. Metropolitan areas rely on intra-city transit systems such as metros, local buses, and last-mile networks. In contrast, metropolitan regions depend on regional mass transit-including suburban rail, rapid regional transit systems (RRTS), expressways, and freight corridors-reflecting their larger geographic scale and multi-nodal structure.

Environmental and demographic characteristics highlight further divergence. Metropolitan areas experience dense urban environmental stresses such as air pollution and heat islands, whereas metropolitan regions face broader ecological pressures, including watershed degradation and peri-urban land conversion. Socially, metropolitan regions display greater demographic heterogeneity, combining urban centres, peri-urban settlers, and rural populations.

5. Similarities Between Metropolitan Area and Metropolitan Region

Table 6.

Key Similarities Between Metropolitan Area and Metropolitan Region.

Table 6.

Key Similarities Between Metropolitan Area and Metropolitan Region.

| Similarity Dimension |

Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Region |

Shared Nature |

| Urban Influence |

Formed by the expansion and dominance of the central city over adjacent suburbs. |

Emerges from the extended influence of the same metropolitan core across wider territories. |

Both spatial units evolve due to the economic power, demographic weight, and service concentration of the core metropolis. |

| Functional Integration |

Daily commuting, service dependencies, labour market alignment with the central city. |

Multi-directional labour flows, inter-city linkages, institutional and economic networks connected to the core. |

Both rely on strong functional ties such as labour mobility, supply networks, and shared institutional frameworks. |

| Role in National Development |

Significant contributor to national GDP, innovation ecosystems, and urban productivity. |

Acts as a larger-scale engine of national development through diversified industrial and service sectors. |

Both represent strategic economic centres and hubs of innovation, investment, and regional competitiveness. |

| Infrastructure Needs |

Requires robust intra-city transit, utility services, affordable housing, and resilient urban systems. |

Requires high-capacity regional mobility, corridor-based infrastructure, multimodal logistics, and wide-scale environmental management. |

Both depend on integrated infrastructure systems to sustain economic growth, mobility, and quality of life. |

| Governance Complexity |

Involves municipal agencies, city corporations, development authorities, and local stakeholders. |

Involves multi-tiered governance across municipalities, districts, and states alongside regional authorities. |

Both require coordinated decision-making across diverse actors to manage growth, services, and investments effectively. |

Despite their differences in scale, governance arrangements, spatial form, and territorial extent, metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions share several foundational characteristics that stem from their relationship with the core metropolitan city. At the heart of both lies the influence of the primary urban centre, which drives economic growth, shapes labour markets, and generates spatial expansion. Whether the built-up fabric is compact or dispersed, both units emerge as outcomes of metropolitan-driven urbanisation processes, where the central city acts as the primary force organising demographic, economic, and infrastructural patterns across surrounding territories.

Functionally, both metropolitan areas and regions exhibit a high degree of interdependence. Labour mobility, institutional networks, and shared economic dependencies tie their respective territories strongly to the metropolitan core. Workers commute into the primary city for employment; firms depend on centralised services and markets; institutions coordinate across urban and regional levels. While the scale of functional linkages differs-short-distance commuting in metropolitan areas versus inter-city flows in metropolitan regions-the underlying principle of functional integration remains common. Both operate as unified socio-economic systems shaped by flows of people, goods, capital, and information.

Both spatial units also play a pivotal role in national development. Metropolitan areas are engines of productivity, housing essential service-sector employment, innovation ecosystems, and dense commercial activity. Metropolitan regions extend this economic influence by integrating industrial corridors, logistics hubs, rural supply chains, and satellite business districts, collectively forming some of the most competitive and dynamic economic spaces within a country. Their shared reliance on robust infrastructure systems underscores another similarity. Whether at the city or regional scale, high-capacity transport networks, reliable utilities, and resilient environmental management systems are essential for supporting population growth, economic activity, and sustainable urbanisation.

Finally, governance complexity is a defining trait of both entities. Managing a metropolitan area requires coordination across municipal bodies, development authorities, and transport agencies, while metropolitan regions require multi-jurisdictional cooperation across districts and states. Despite the scale difference, both demand integrated planning, stakeholder collaboration, and strategic governance frameworks to ensure balanced and sustainable development.

6. Case Studies: Indian Metropolitan Areas and Metropolitan Regions

The distinction between metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions is particularly relevant in the Indian context, where rapid urbanisation, significant rural–urban migration, and expanding economic corridors have reshaped traditional urban boundaries. Cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru have evolved far beyond their municipal limits, giving rise to complex, multi-jurisdictional regional systems. These systems integrate dense urban cores with suburban belts, satellite cities, peri-urban villages, industrial zones, and logistics corridors. As a result, national and state planning authorities increasingly use two separate classifications-metropolitan area and metropolitan region-to capture the varying spatial, functional, and governance realities of contemporary Indian urbanisation. These classifications help clarify the varying territorial scales used for census enumeration, infrastructure planning, economic development, and regional governance.

Figure 3.

Representation of Metropolitan Region.

Figure 3.

Representation of Metropolitan Region.

Figure 4.

Representation of Metropolitan Area.

Figure 4.

Representation of Metropolitan Area.

6.1. Definitions

Metropolitan Area

• A core city (large urban centre) and the contiguous built-up area around it.

• Defined primarily based on population density, urbanisation, commuting patterns, and continuous development.

• Example: Delhi Urban Agglomeration (Delhi + contiguous built-up areas in NCR).

Metropolitan Region

• A larger geographical, economic and functional territory that includes:

○ the metropolitan area,

○ surrounding peri-urban, semi-urban, rural towns,

○ industrial clusters, satellite towns, and regional corridors.

• Defined based on economic linkages, regional mobility, governance, and long-term spatial planning.

• Example: Delhi NCR (covers Delhi NCT and districts of Haryana, UP, Rajasthan).

6.2. Key Differences

Table 7.

Key Differences.

Table 7.

Key Differences.

| Aspect |

Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Region |

| Scale |

Smaller, urban-focused |

Larger, multi-city, regional |

| Core Element |

A principal city + built-up suburbs |

Includes the metro area + satellite towns, rural hinterlands |

| Criteria |

Population, density, commuting, contiguity |

Economic linkages, governance, regional planning |

| Urban Extent |

Continuous urban footprint |

Discontinuous, multi-nodal settlement system |

| Governance |

City-level bodies (municipal corporations) |

Regional development authorities (e.g., NCRPB, MMRDA) |

| Planning Focus |

Local land use, city services, transit |

Regional transport corridors, multi-city planning |

| Examples |

Mumbai UA, Bengaluru UA |

Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), Bengaluru Metropolitan Region (BMR) |

The table on differences and similarities between metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions highlights the specific criteria that distinguish the two concepts. Metropolitan areas are defined primarily by population density, continuous built-up morphology, and short-distance commuting patterns around a central city. They represent compact urban zones that are managed largely by municipal corporations or local development authorities. Metropolitan regions, on the other hand, are defined by broader economic linkages, regional mobility patterns, governance jurisdictions, and long-term spatial planning needs. They include not only the contiguous urban footprint but also surrounding districts, satellite towns, rural hinterlands, industrial clusters, and economic corridors. The contrast between examples such as the Delhi Urban Agglomeration (a metropolitan area) and the Delhi National Capital Region (a metropolitan region spanning multiple states) illustrates how the two frameworks operate at different territorial scales and planning logics.

6.3. Key Similarities

Table 8.

Key Similarities.

Table 8.

Key Similarities.

| Aspect |

Shared Characteristics |

| Urban Influence |

Both are shaped by economic and functional influence of a major city. |

| Functional Linkages |

Both depend on strong commuting, job–housing relationships, and transport systems. |

| Population Concentration |

Both host large populations, high density zones, and diversified economic activities. |

| Planning Needs |

Both require coordinated planning in mobility, infrastructure, land use, and environment. |

| Economic Role |

Both act as regional engines of growth, innovation, and investment. |

Despite these differences, the comparative analysis also reveals important similarities. Both metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions grow out of the economic and functional dominance of a central metropolis, which anchors labour markets, consumption networks, infrastructure systems, and investment flows. Both host large, dense populations and require coordinated planning in mobility, land use, environmental management, and service delivery. Moreover, both act as engines of national economic growth, attracting capital, talent, and innovation. In simple terms, the metropolitan area represents the compact urban core and its immediate suburbs, while the metropolitan region represents the broader territorial system influenced by that core. Thus, the metropolitan area can be understood as a subset of the wider metropolitan region, and effective planning in India increasingly requires strategies that integrate the two scales rather than treating them as isolated units.

Simplified Explanation

• Metropolitan Area = City + Suburbs (continuously built-up urban area)

• Metropolitan Region = Metropolitan Area + Surrounding Districts, Towns, Industrial Zones

So, the Metropolitan Area is a subset of the larger Metropolitan Region.

6.4. Indian Context Examples

Delhi

• Metropolitan Area: Delhi Urban Agglomeration

• Metropolitan Region: National Capital Region (NCR)

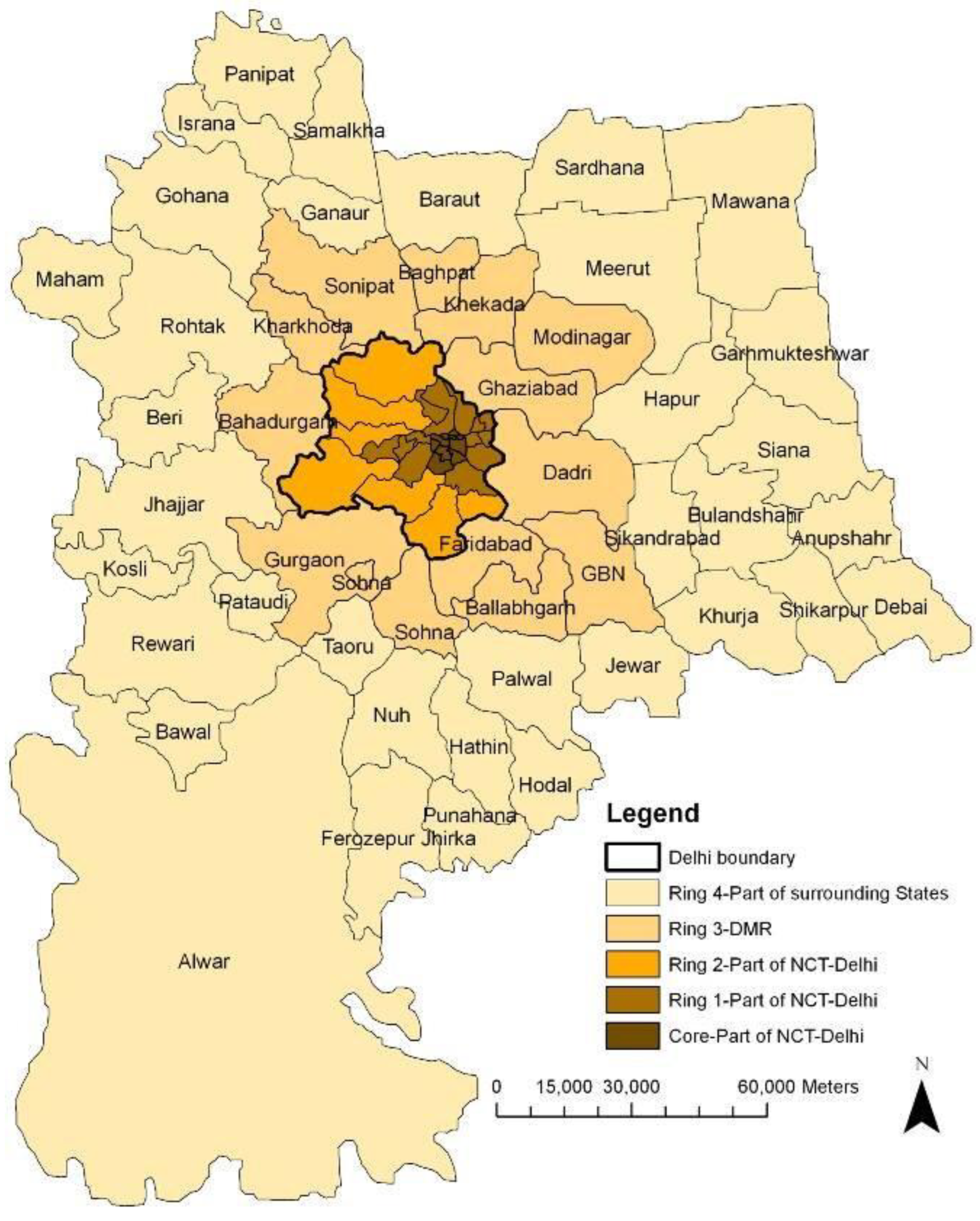

In Delhi, the distinction between the metropolitan area and the metropolitan region clearly illustrates the multi-scalar nature of Indian urbanisation. The Delhi Metropolitan Area, commonly referred to as the Delhi Urban Agglomeration (UA), consists of the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi and the immediately contiguous built-up extensions that merge seamlessly with the city's core. This includes dense urban districts such as New Delhi, South Delhi, Karol Bagh, and the rapidly urbanising peripheries of Rohini and Dwarka. The metropolitan region, however, is far more expansive. The National Capital Region (NCR)-administered by the NCR Planning Board-extends across the neighbouring states of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan, incorporating major economic nodes such as Gurugram, Noida, Faridabad, Ghaziabad, Sonipat, Meerut, and Alwar. This region forms a vast, polycentric metropolitan system marked by shared labour markets, inter-city mobility flows, regional transit networks, industrial corridors, and integrated economic linkages. Thus, the Delhi UA represents the compact, contiguous city, whereas the NCR represents the full functional footprint of the metropolis, spanning multiple states and diverse settlement patterns.

Mumbai

• Metropolitan Area: Greater Mumbai + continuous built-up areas

• Metropolitan Region: Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), includes Thane, Navi Mumbai, Kalyan-Dombivli, etc.

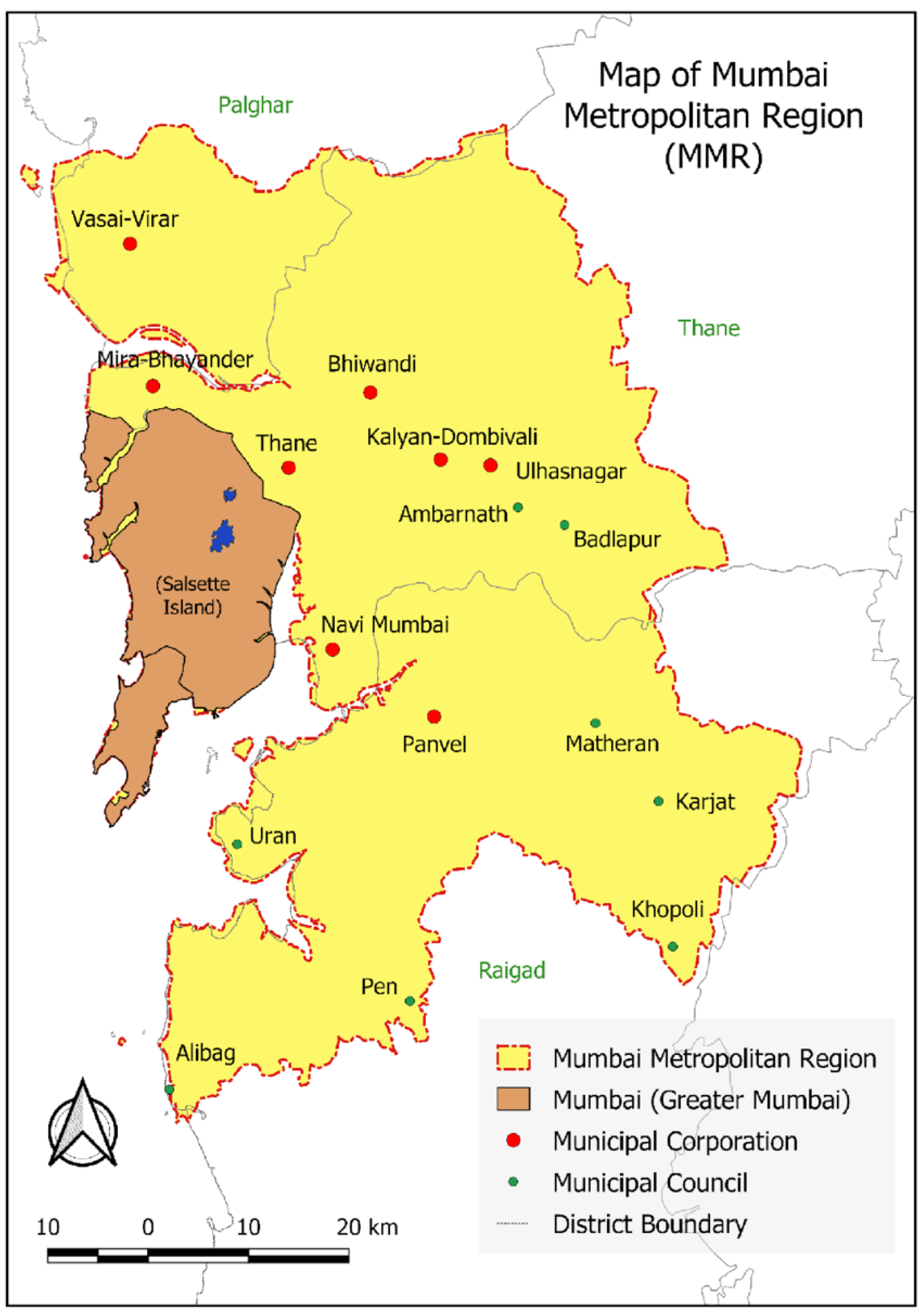

Mumbai presents one of India’s most pronounced distinctions between a metropolitan area and a metropolitan region, shaped by its unique coastal geography, intense land pressures, and long history of suburban expansion. The Mumbai Metropolitan Area, broadly identified as Greater Mumbai and its contiguous built-up extensions, includes the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) along with adjacent high-density suburbs such as Bandra, Andheri, Borivali, Chembur, and Kurla. This compact urban footprint reflects the linear north–south development pattern constrained by the coastline and reinforced by suburban rail corridors. Beyond this dense metropolitan area lies the much larger and more complex Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), governed by the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA). The MMR encompasses multiple municipal corporations and councils including Thane, Navi Mumbai, Kalyan-Dombivli, Vasai-Virar, Mira-Bhayandar, and several growth centres and industrial clusters that serve as major employment and residential nodes. The region is highly polycentric, with nodes such as Navi Mumbai and Thane functioning almost as independent cities while retaining strong economic, labour, and mobility linkages with the Mumbai core. Characterised by diverse land-use patterns, a vast commuter shed, and significant logistics and industrial activities, the MMR embodies the wider functional landscape of the Mumbai urban economy-far exceeding the boundaries of the contiguous metropolitan area.

Figure 5.

Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

Figure 5.

Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

Figure 6.

Delhi Metropolitan Area and Region.

Figure 6.

Delhi Metropolitan Area and Region.

Bengaluru

• Metropolitan Area: Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) + adjacent urban extensions

• Metropolitan Region: Bengaluru Metropolitan Region (BMR), covering multiple taluks and satellite towns like Nelamangala, Anekal.

Bengaluru offers a distinct but comparable example of the metropolitan area–metropolitan region relationship. The Bengaluru Metropolitan Area is centred on the jurisdiction of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), encompassing the densely built-up urban core, major commercial districts, IT hubs, and inner suburban extensions such as Whitefield, Yelahanka, and Kengeri. This area reflects the contiguous urban footprint driven by Bengaluru’s growth as India’s leading IT and innovation centre. Beyond this compact zone lies the Bengaluru Metropolitan Region (BMR), a much larger territorial system governed by the Bengaluru Metropolitan Region Development Authority (BMRDA). The BMR includes multiple taluks-such as Anekal, Nelamangala, Hoskote, and Devanahalli-as well as emerging satellite towns, industrial belts, logistics hubs, and peri-urban corridors shaped by airport-led and highway-led development. Unlike the monocentric BBMP area, the BMR is polycentric and discontinuous, integrating rural, semi-urban, and urban settlements into a broader regional economy. Together, they reflect Bengaluru’s transition from a compact metropolitan area to a multi-nodal metropolitan region with regional-scale mobility, land-use dynamics, and governance needs.

One-Line Summary

A Metropolitan Area is a compact, densely urbanised core city system that emerges as a natural outcome of the scale of the metropolitan core's economy, with fringe areas continuously growing in line with city size. At the same time, a Metropolitan Region is a broader, multi-nodal economic territory built around that core, defined by government legislation, such as the Metropolitan Planning Committee.

7. Governance and Policy Implications

The emergence of metropolitan regions in India and globally highlights the pressing need for integrated regional governance frameworks that extend beyond traditional municipal boundaries. Unlike metropolitan areas, which can often be managed by a single municipal corporation or a limited set of city-level agencies, metropolitan regions encompass multiple districts, state jurisdictions, and autonomous local bodies. This multi-scalar composition makes coordination essential for effective planning and implementation. Regional governance institutions-such as the NCR Planning Board, MMRDA, and BMRDA-play a critical role in harmonising policies across transport, land use, environment, and infrastructure. Their efforts are especially crucial for ensuring multi-state coordination in cases like the Delhi NCR, unified standards for environmental regulation, and region-wide systems for data sharing, spatial planning, and service delivery. Without such regional coordination, metropolitan regions risk fragmented development, duplication of investments, and inefficient use of shared resources.

Transportation planning within metropolitan regions demands a fundamentally different approach from metro-area mobility planning. While metropolitan areas focus on intra-city transit systems such as metro rail, bus rapid transit, and last-mile connectivity, metropolitan regions require regional-scale mobility infrastructures capable of supporting long-distance commuting and inter-city movement. This includes rapid rail systems such as the RRTS, suburban rail expansions, expressways, ring roads, and multi-modal logistics hubs connecting road, rail, air, and port networks. These systems are essential not only for facilitating labour market integration across the region but also for enabling the efficient movement of goods across industrial clusters, peri-urban production zones, and major consumption centres. Effective regional transportation planning improves accessibility, reduces congestion in core cities, and promotes spatial rebalancing by enabling the growth of satellite towns and secondary urban nodes.

Land-use planning also reflects the contrast between metropolitan areas and regions. Metropolitan areas typically employ zoning regulations, densification strategies, and Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) to manage urban form and support compact development. Metropolitan regions, by contrast, must consider broader territorial instruments such as green belts to manage sprawl, regional growth centres to distribute development, and planned satellite towns to relieve development pressure on the core. These regional land-use strategies enable more balanced spatial development and prevent the unregulated expansion of peri-urban areas.

From an economic perspective, metropolitan regions offer greater competitiveness due to their larger markets, diversified resource base, and enhanced logistics connectivity. Their polycentric structure allows economic activities to cluster efficiently while reducing pressure on the central city. Finally, climate and sustainability imperatives demand regional approaches, as issues such as flood management, watershed protection, and air quality transcend municipal boundaries. Effective regional planning thus becomes essential for building climate-resilient metropolitan systems and ensuring long-term environmental sustainability.

8. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that metropolitan areas and metropolitan regions, while interconnected, represent fundamentally different spatial and functional constructs in urban and regional planning. The metropolitan area operates at a compact, city-centric scale characterised by dense built-up morphology, intra-city mobility, and localised service and infrastructure pressures. Research in urban growth, accessibility, and travel behaviour demonstrates that such areas typically experience challenges related to congestion, land scarcity, heat islands, and short-range mobility demands, all of which require planning tools such as TOD, densification, zoning, and intra-city transit integration (Sharma, Kumar & Dehalwar, 2024; Yadav, Dehalwar & Sharma, 2025; Sharma & Dehalwar, 2025). In contrast, the metropolitan region functions at a broader, interlinked territorial scale. Studies of East Asian megaregions and European polycentric regions consistently show that economic corridors, multi-nodal structures, and regional commuting patterns shape metropolitan regions far more strongly than morphological contiguity (Xiao et al., 2025; van Dijk et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025). The regional scale therefore becomes essential for integrating peri-urban growth, satellite towns, rural economies, and regional environmental systems into a single planning and governance framework.