The following sub-sections introduce the main findings for AI on Disciplinary Distribution, Geographic and Institutional Patterns and Publication Typology and Sources.

3.1. Disciplinary Distribution

A scientometric analysis of academic disciplines was employed to understand the general structure and development of the AI research field. Each publication was categorized according to the classification provided by the Web of Sciences based on the selected publication medium, which may belong to more than one thematic research area.

The distribution of publication data revealed some noteworthy patterns. Although engineering and computer science research areas each have the largest number of contributions related to AI, there are other areas where research on this technology is being conducted.

Moreover, the data presented in

Table 1 reveal that most technology-related research remains predominantly concentrated on the development and refinement of the technologies themselves rather than on their broader domain-specific applications. This trend highlights the early-stage maturity of Artificial Intelligence research, which is still oriented toward algorithmic and computational advances.

Looking forward, it will become increasingly essential to investigate the implications and transformative potential of AI across diverse disciplinary perspectives ranging from materials science, physics, and business economics to more specialized domains such as nuclear radiology, neuroscience, and oncology. For instance, in medical imaging analysis, AI-driven diagnostic systems have demonstrated substantial reductions in the time required for clinical evaluation, thereby enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of medical decision-making processes.

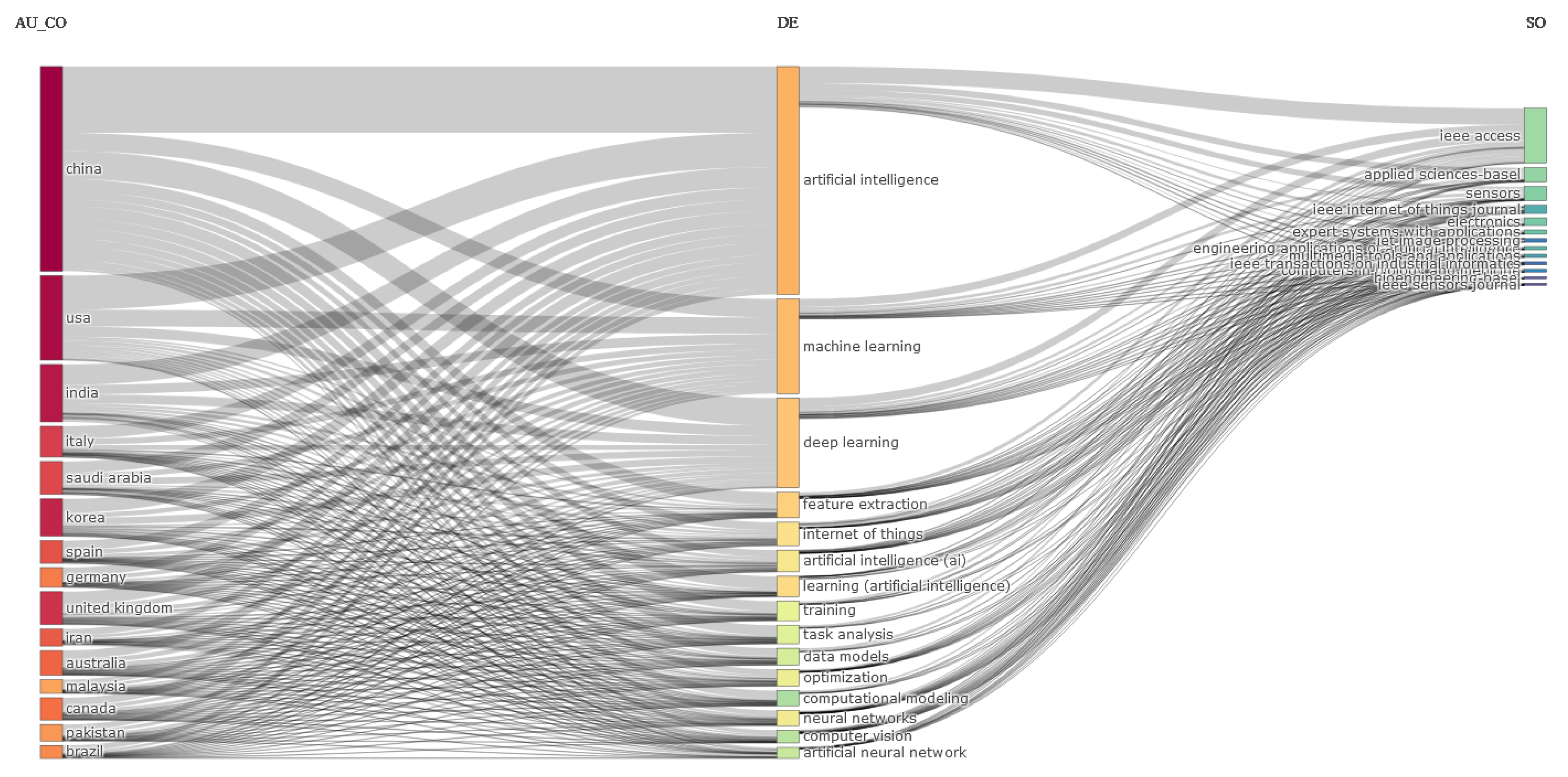

3.3. Publication Typology and Sources

The choice of publication medium significantly influences both the visibility and scholarly impact of research output. Therefore, it is relevant to examine the types of media preferred by researchers to communicate research findings to the scientific community of AI.

Since the publication (document) type is specified for all AI records retrieved from the Web of Science, it is possible to analyze the overall distribution of publication formats within this field. As shown in

Table 3, the majority of AI outputs, on average 81.60%— were published as journal articles. This predominance is noteworthy, as conferences are often assumed to be the primary venue for disseminating cutting-edge technological research. However, journals typically reach a broader and more enduring readership than specialized conferences [

9].

To extend this analysis, the distribution of publications across conferences and journals is examined in detail. Conference papers, although rapidly published, provide a limited temporal and audience scope and are often constrained to event participants. Conversely, journals offer more rigorous peer review processes and greater dissemination potential, despite longer publication times.

Within this dataset, the number of articles per journal is considerably higher than the number of papers published in conferences, underscoring a structural preference for journal-based communication in the AI research field.

Regarding publication venues,

IEEE Access stands out as the leading outlet, with 3,519 articles, followed by

Applied Sciences (Basel) with 2,019 articles, as shown in

Table 4. These two journals exemplify the increasing tendency of open-access platforms to dominate AI dissemination. Notably, the list of top publication sources reflects the interdisciplinary nature of AI; beyond technology-oriented outlets such as

Electronics or

Expert Systems with Applications, high publication activity is also found in applied domains such as energy (

Energies) and medical sciences (

Cureus Journal of Medical Science, 642 articles). This distribution demonstrates AI’s integration of AI across technological, scientific, and clinical contexts, reinforcing its role as a cross-cutting discipline.

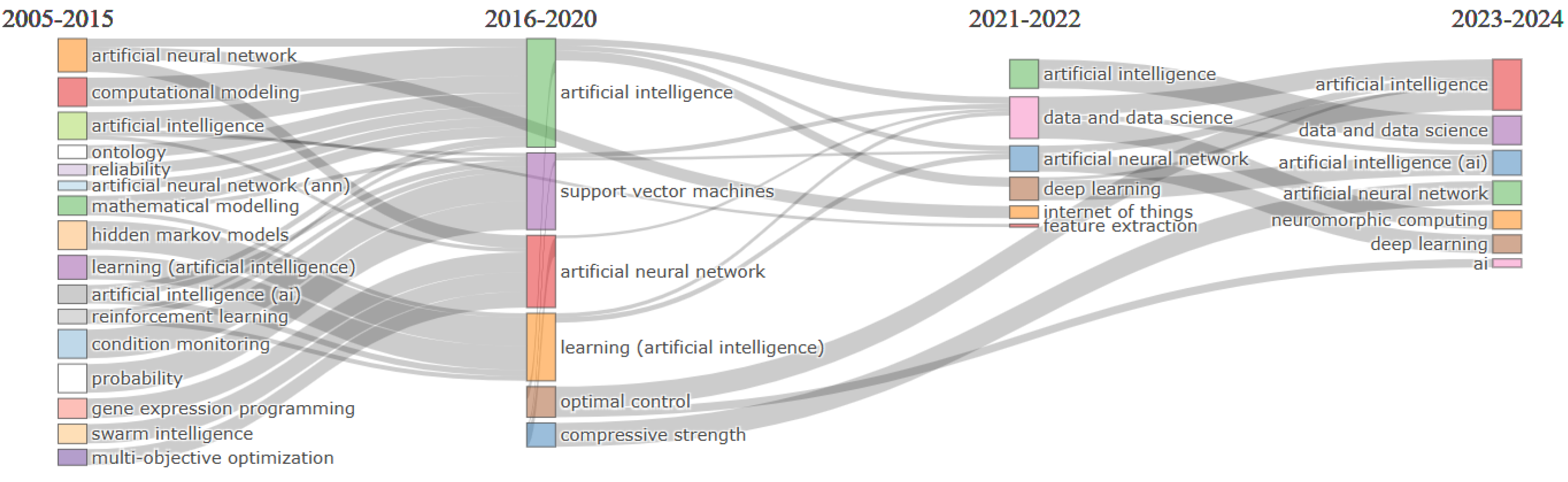

3.4. Keyword Evolution

Keywords are efficient resources for representing and classifying the content of articles in abstract and condensed forms. From one perspective, keywords provide the basis for analyzing the themes and key aspects that represent a particular research area. Rapid identification of novel topics can be achieved by analyzing the emergence of keywords over a given period. The scientometric study presented in this work extracted 221,942 author keywords and 77,420 source indexed keywords from the considered dataset. Regarding the average distribution of keywords per publication, it was observed that only between three and six keywords are generally used to attract scientific attention. This observation is not specific to AI as publishers often specify the minimum and/or maximum number of keywords per publication.

The rankings of the main keywords with high frequencies are present in

Table 5. The results indicate that research activities in the field of Artificial Intelligence are primarily concentrated on technological core itself—topics such as

Artificial Intelligence,

Machine Learning,

Deep Learning,

ChatGPT,

Big Data, and the

Internet of Things. However, the analysis also reveals the emergence of context-driven subjects beyond core technology, including social and global phenomena such as

COVID-19, whose presence in the literature has grown considerably in recent years. This trend reflects the adaptability of AI research to external challenges and its expanding role in addressing multidisciplinary problems.

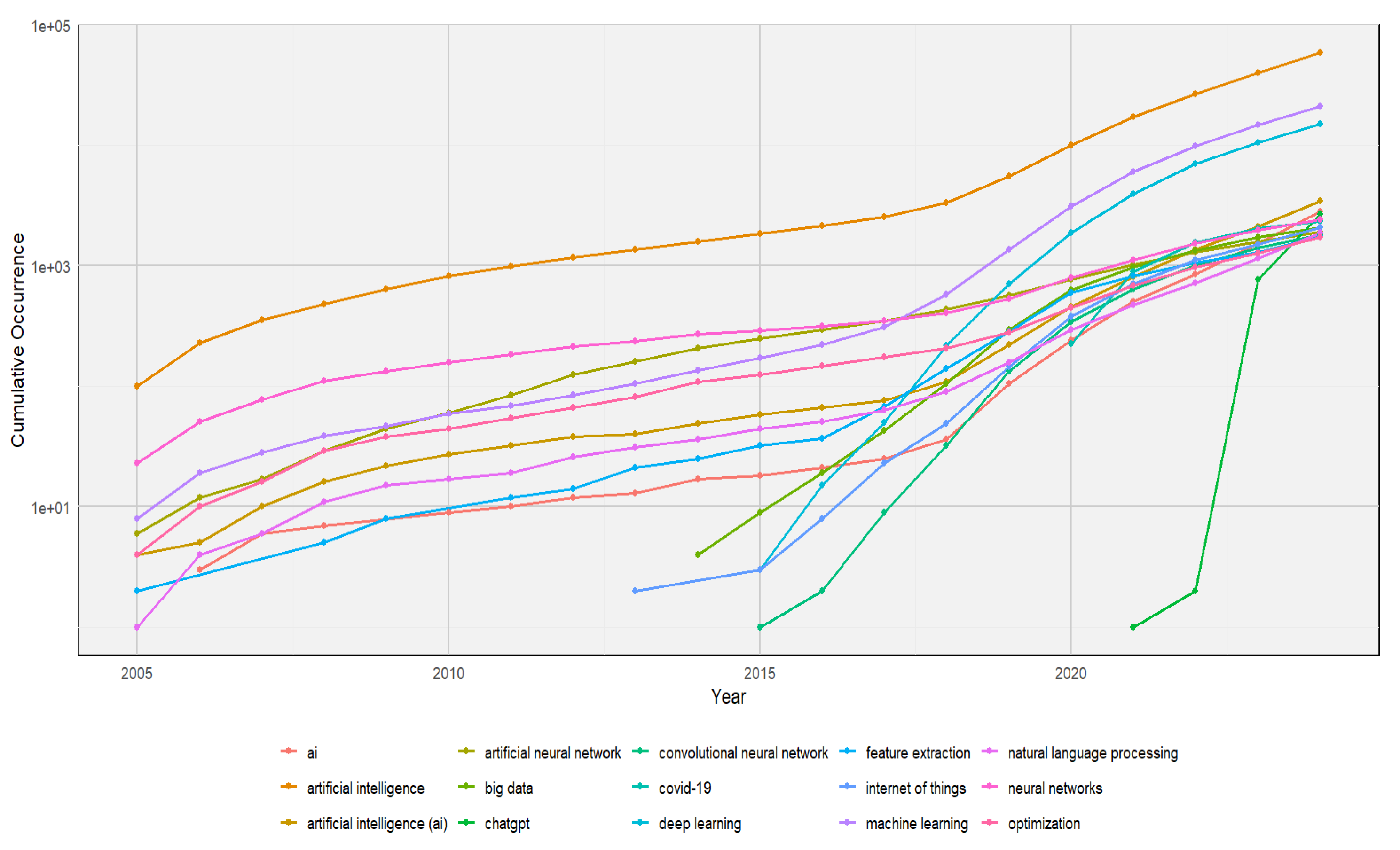

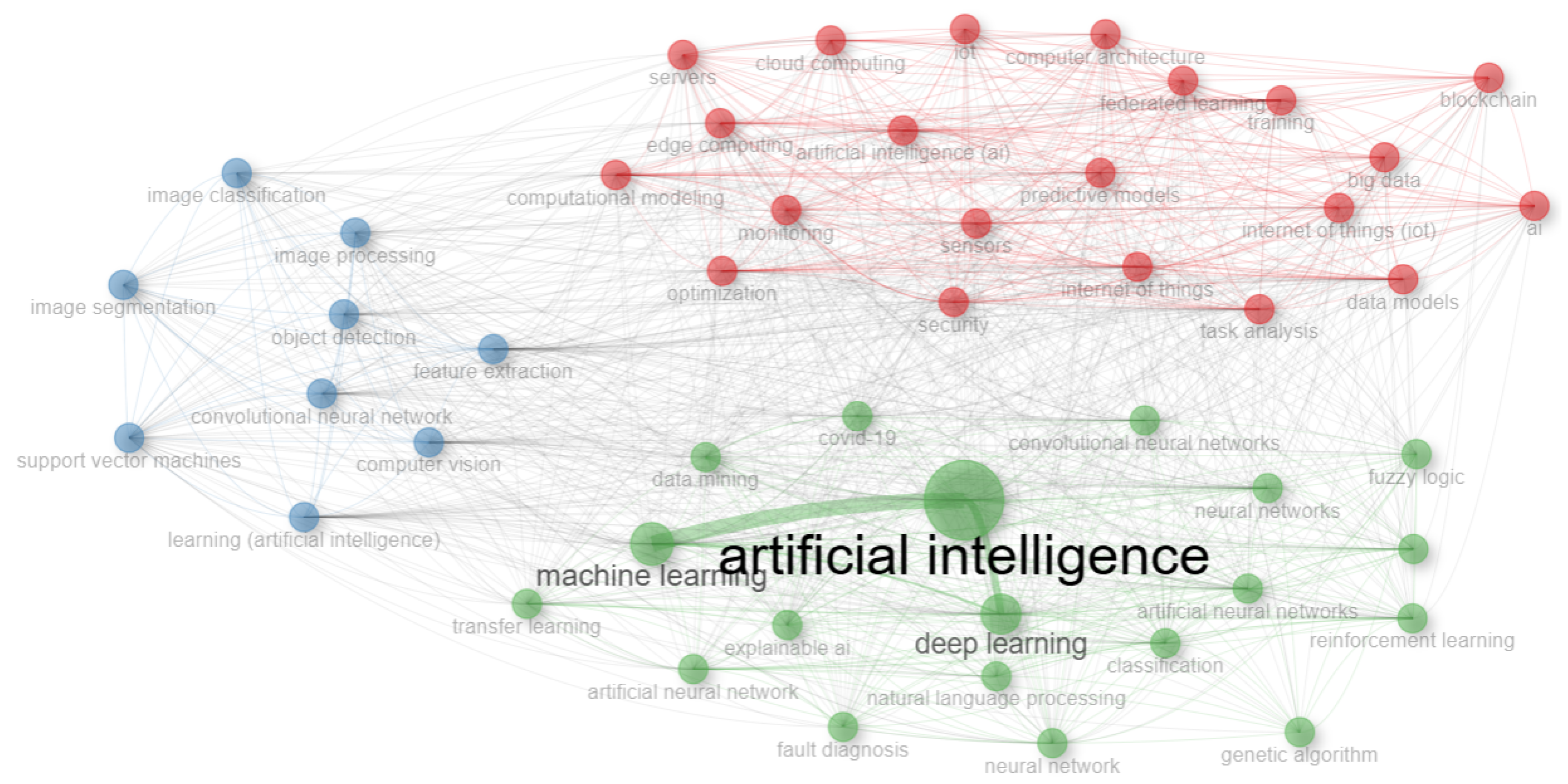

Figure 1 illustrates the annual evolution of the top 15 keywords associated with AI research between 2005 and 2024. The data reveal a sharp and sustained increase in the occurrence of core technological terms such as

Artificial Intelligence,

Machine Learning, and

Deep Learning.

These core technological terms began accelerating markedly from 2019 onward, with the widespread diffusion of AI-driven applications across multiple domains ranging from natural language processing and computer vision to autonomous systems and predictive analytics marking a transition from theoretical exploration to large-scale technological adoption.

The term COVID-19 emerged in 2020 as a context-specific keyword that rapidly gained prominence during the global pandemic. Its trajectory reflects how AI methodologies have been repurposed to address urgent societal challenges, particularly in medical diagnostics, epidemiological modeling, and healthcare decision support. This adaptation exemplifies the flexibility of AI in generating rapid data-driven responses under crisis conditions.

Although COVID-19 appears a with lower overall frequency than foundational concepts, its inclusion underscores the expanding versatility of AI research and its integration into multidisciplinary contexts. Moreover, secondary yet highly correlated terms such as Prediction, Classification, and Model highlight the growing analytical focus on data processing, optimization, and inference across diverse knowledge areas with engineering-specific applications such as the Internet of Things or Big Data.

Overall,

Figure 1 demonstrates the consolidation of Artificial Intelligence and its subfields as the dominant and continually expanding areas of scientific inquiry. The consistent upward trend of key terms over time confirms the centrality of AI in addressing complex, data-intensive problems, while the emergence of new thematic axes indicates its transition toward mature, application-oriented research. Consequently, longitudinal keyword analysis proved to be an effective instrument for detecting emerging topics, understanding thematic evolution, and anticipating future directions for AI research.

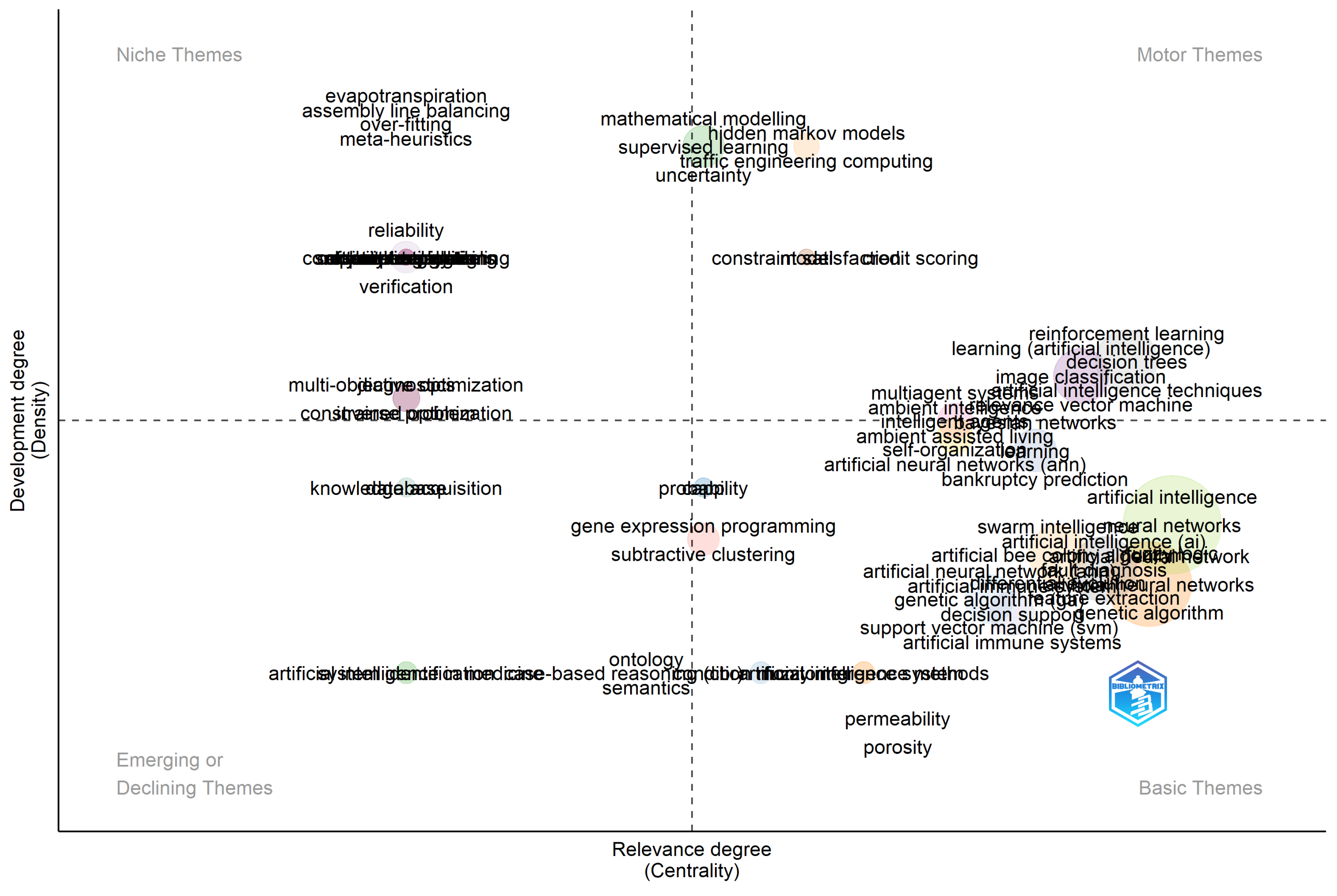

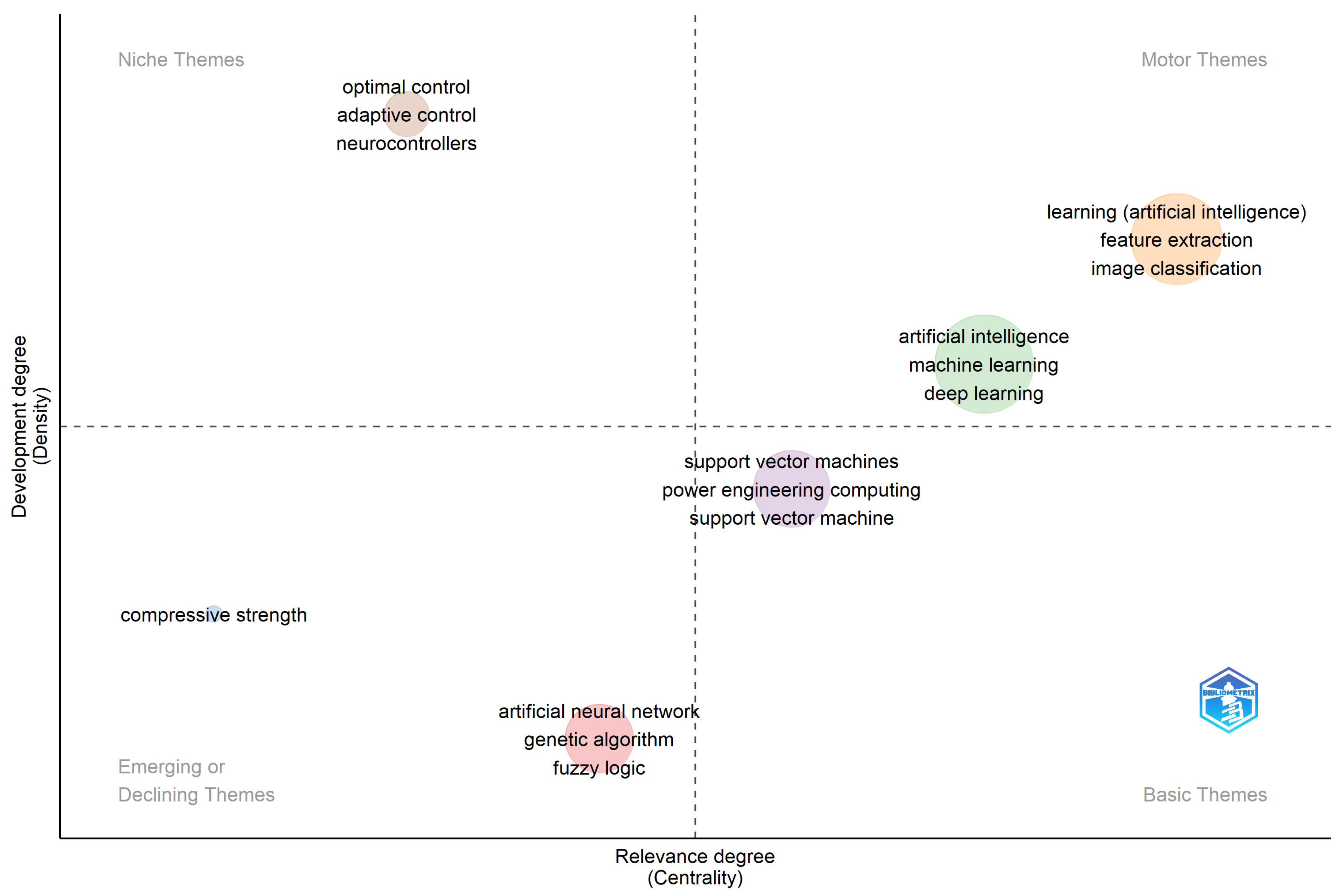

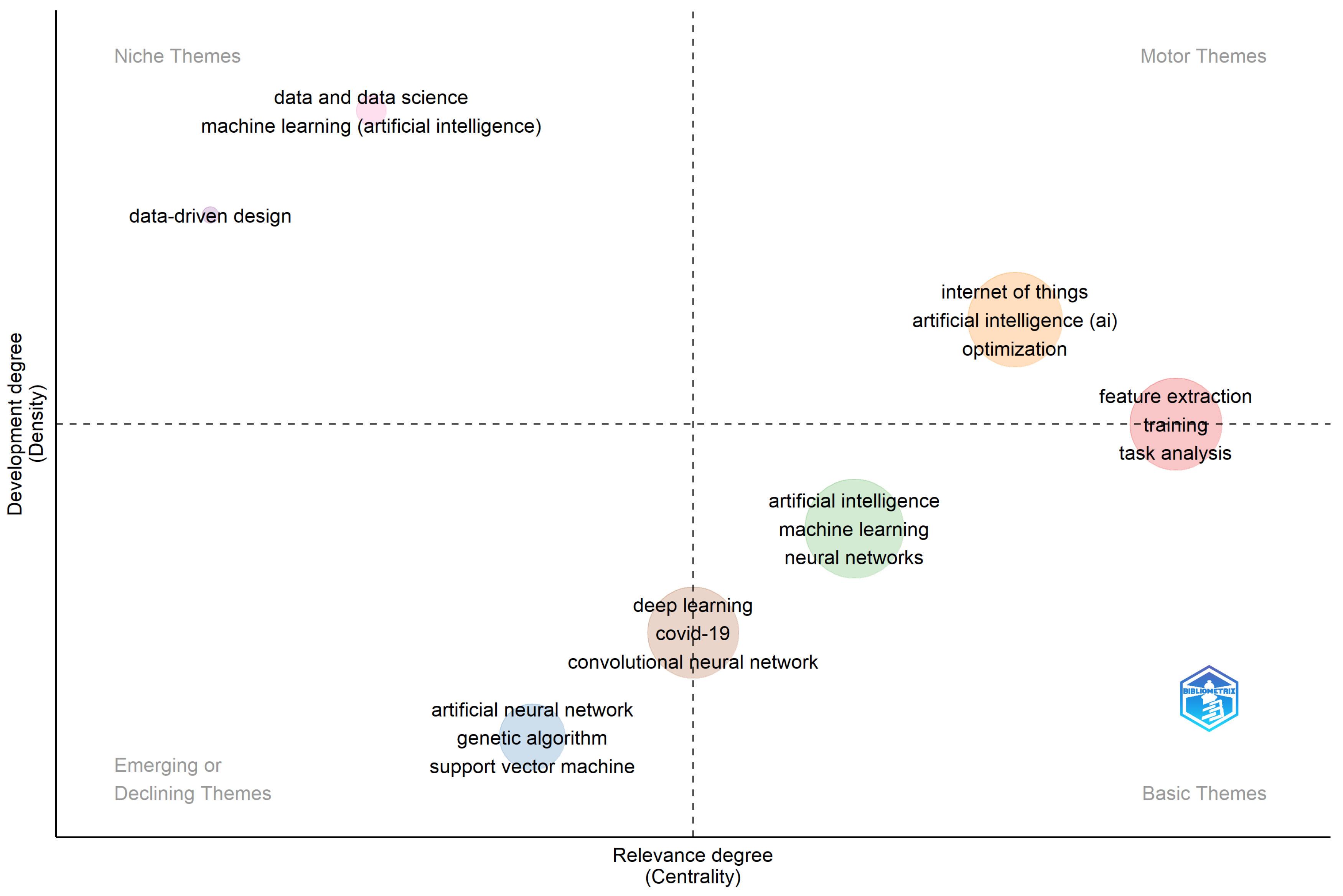

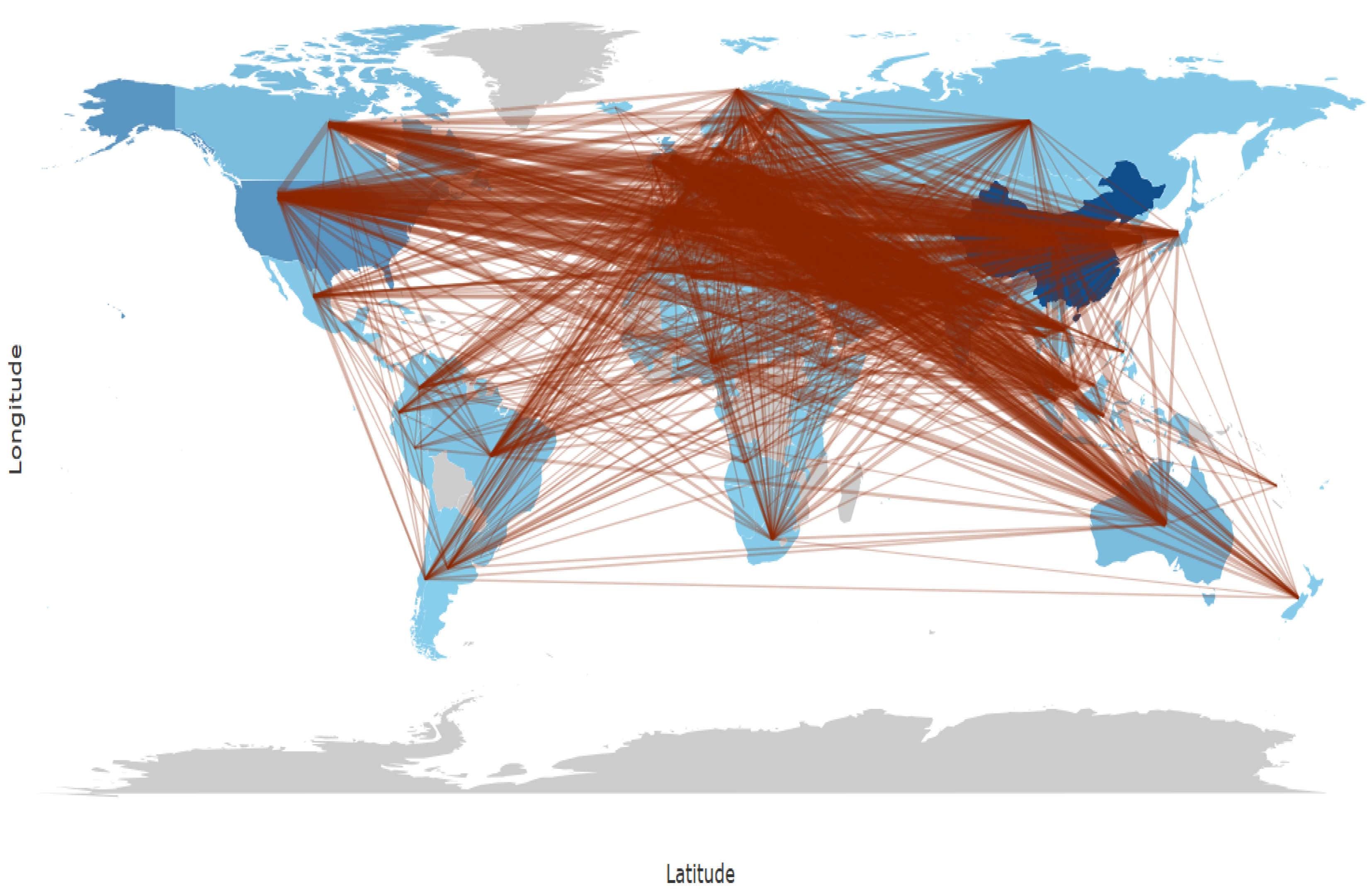

3.5. Thematic Clusters and Collaboration Graphs

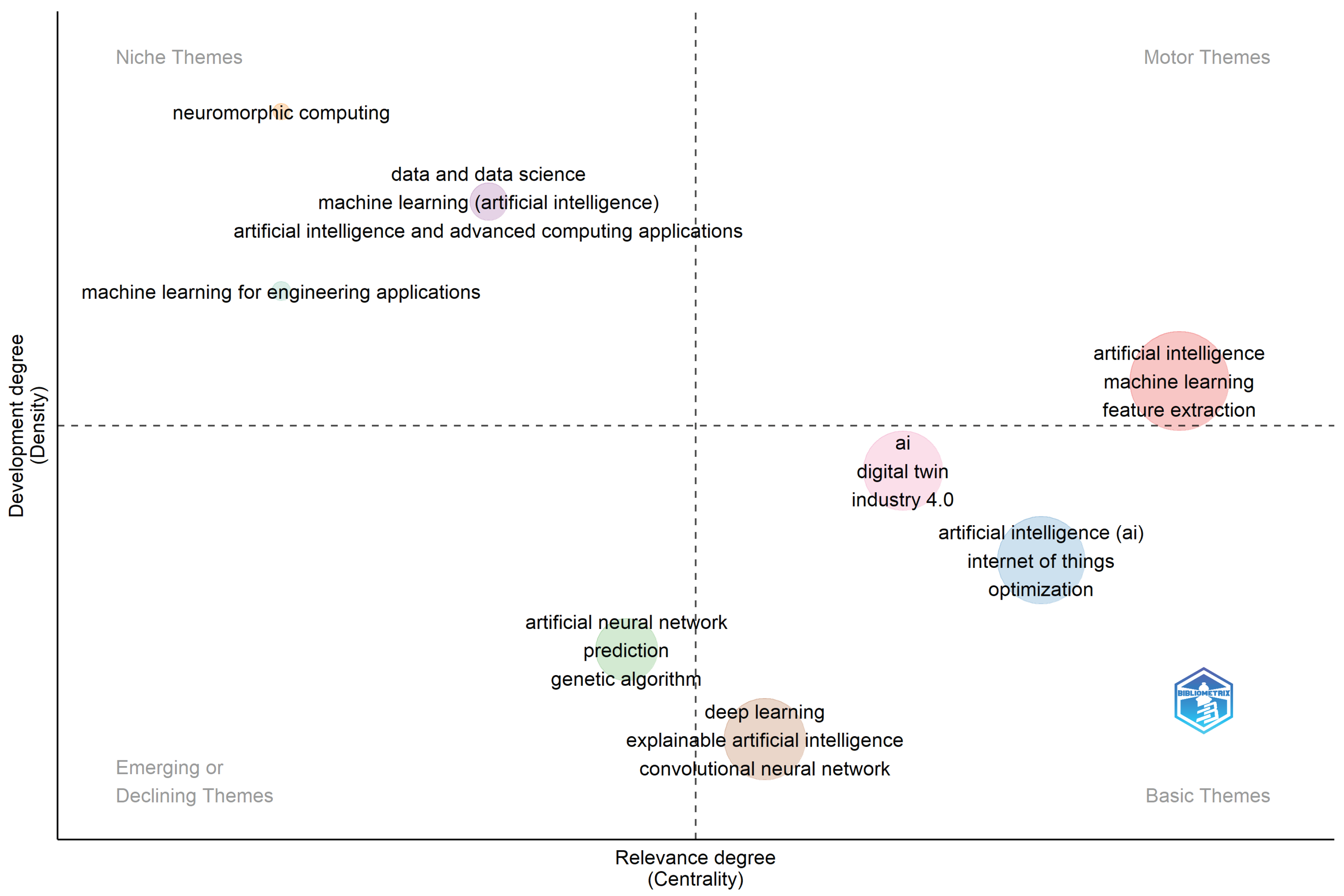

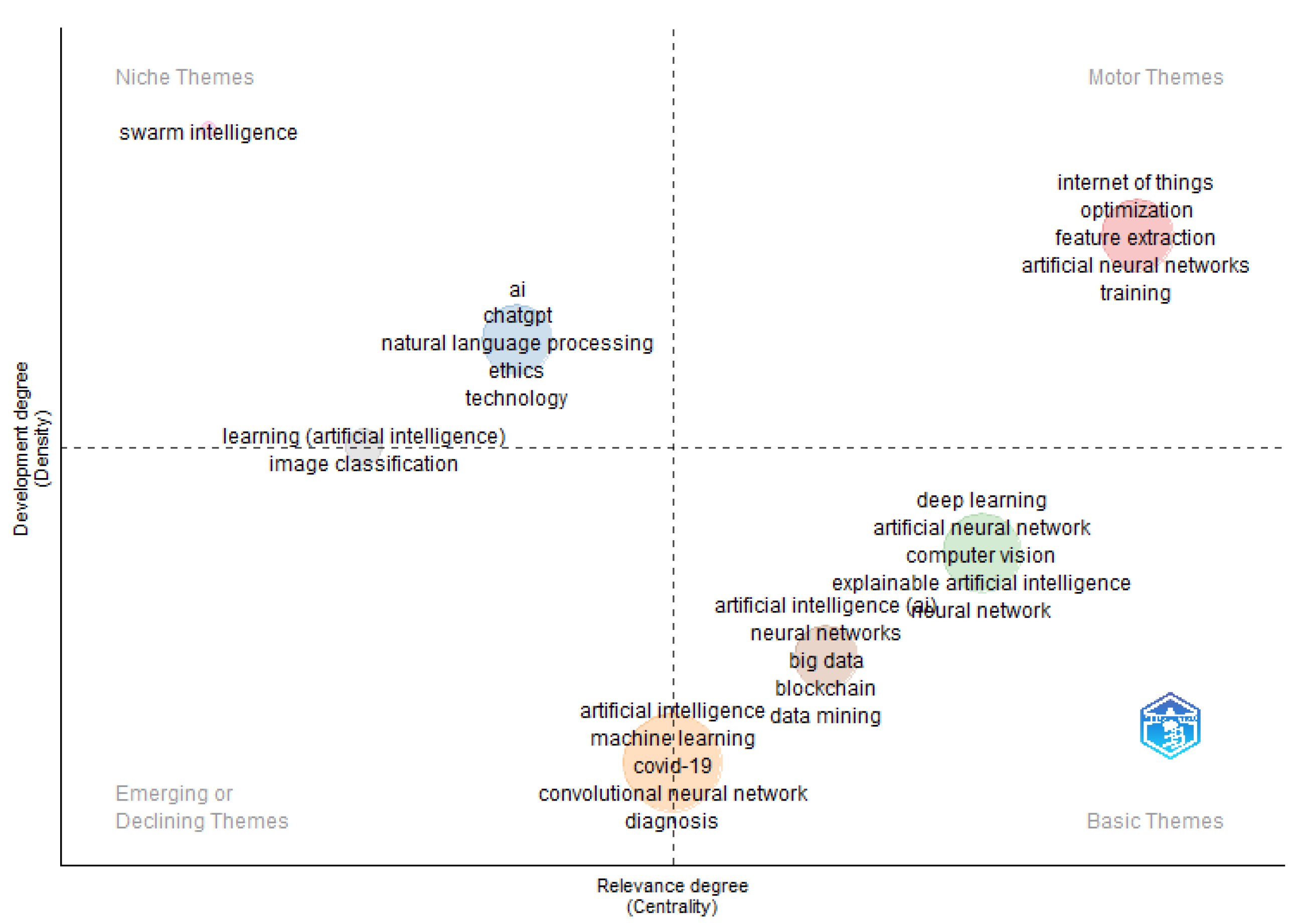

The thematic map shown in

Figure 2—generated in

RStudio using the

Bibliometrix environment illustrates the conceptual organization of AI research derived from the keyword co-occurrence networks. The axes represent

Centrality (horizontal) and

Density (vertical), which measure the thematic relevance and internal development of the research clusters, respectively. The map divides the field into four quadrants:

Motor,

Basic,

Niche, and

Emerging or Declining Themes, each corresponding to a phase of maturity.

In the upper-right quadrant (Motor Themes), highly developed and central topics—such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Optimization, Feature Extraction, Artificial Neural Networks, and Training—form the technological core of AI research. These themes exhibited both high relevance and density, indicating strong internal coherence and influence across multiple domains. They represent consolidated areas of engineering applications and are key drivers for innovation in automation, smart systems, and industrial intelligence.

The lower-right quadrant (Basic Themes) contains fundamental yet broad topics that support the conceptual backbone of the field. Here, terms related to AI such as Deep Learning, Machine Learning, Computer Vision, Big Data, Data Mining, Neural Networks, and Explainable AI (XAI) are dominant. These keywords represent the methodological foundation upon which most AI applications are built, serving as transversal enablers for fields including medicine, robotics, and predictive modeling. This centrality suggests that research in these areas will remain influential in shaping the future trajectory of AI.

In the upper-left quadrant (Niche Themes), more specialized and self-contained topics emerge, including Swarm Intelligence, which reflects active but narrower lines of investigation based on decentralized, nature-inspired systems. Other keywords such as Ethics, Natural Language Processing, Technology, and ChatGPT also appear in this zone, signaling the rise of subfields that are rapidly gaining importance but remain under methodological consolidation. These areas represent potential opportunities for high-impact research as AI expands into socially and linguistically complex domains.

Finally, the lower-left quadrant (Emerging or Declining Themes) groups topics characterized by low centrality and density, such as Artificial Intelligence (general term), Diagnosis, and COVID-19. While some may correspond to declining interest, others-such as pandemic-related applications—illustrate time-bounded surges of scientific activity triggered by global events. This quadrant also represents the potential areas for future revival or interdisciplinary integration.

Overall, the thematic map demonstrated that AI research simultaneously consolidates mature domains and generates new areas of inquiry. The coexistence of strongly established clusters (e.g., deep learning, IoT) with emerging ones (e.g., ethics, ChatGPT, swarm intelligence) highlights the dynamic and multidisciplinary nature of the field, where technical, ethical, and societal dimensions increasingly converge.

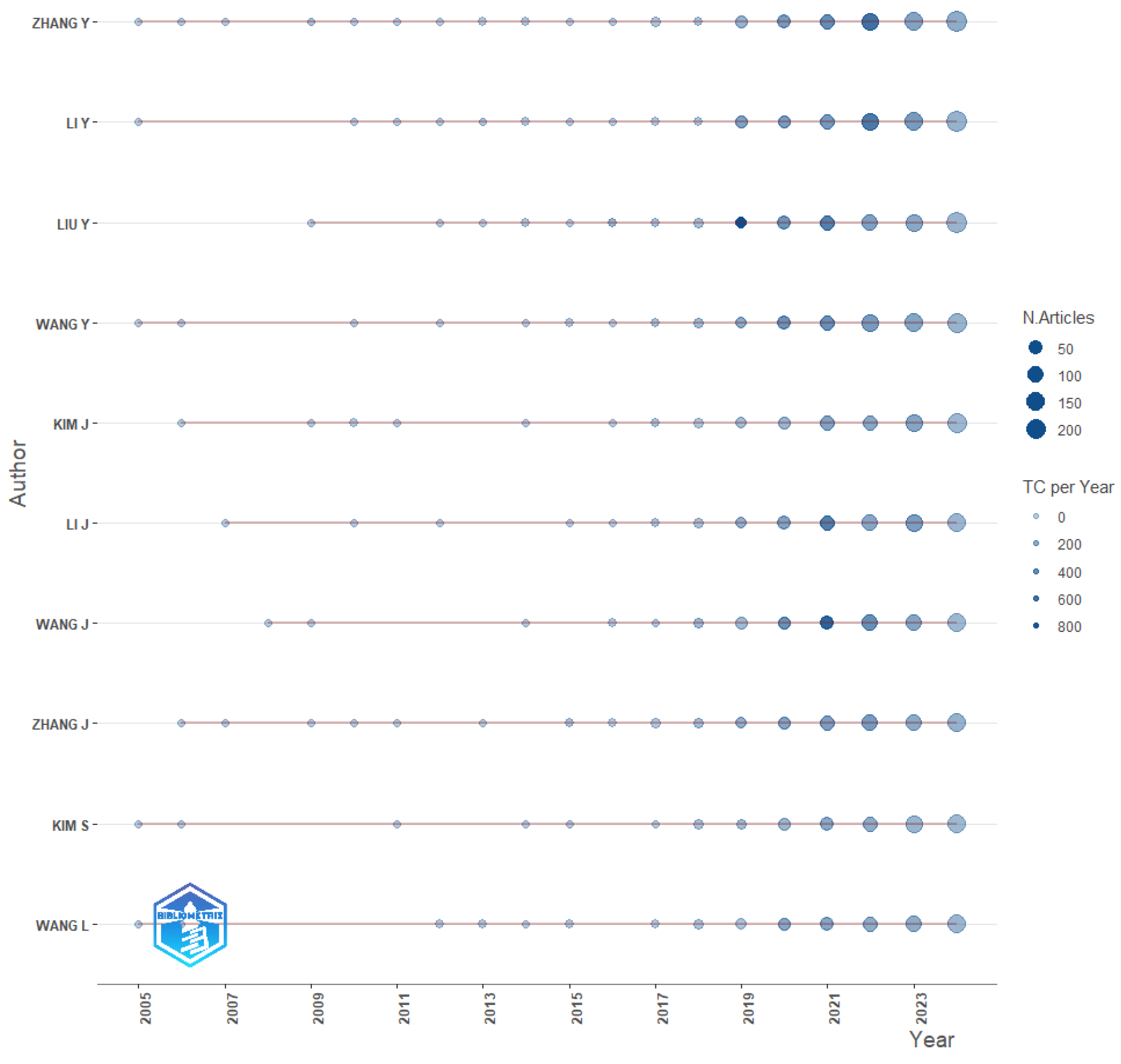

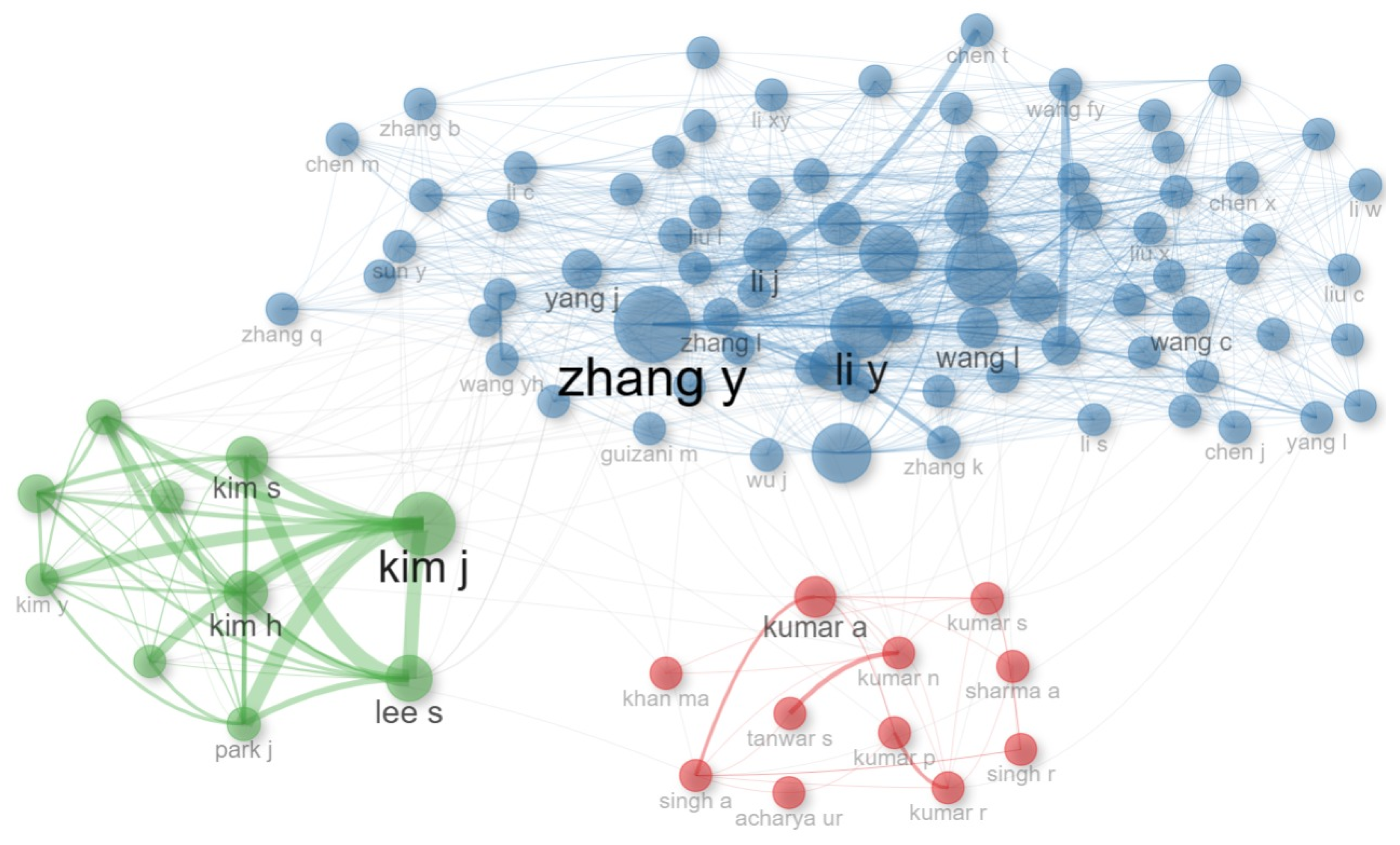

Figure 3 expands the thematic analysis by depicting the temporal evolution of author productivity and its impact within the AI research domain. Each horizontal line represents one of the top 10 leading authors, the bubble size corresponds to the number of published articles (

N. Articles) and the bubble shade intensity reflects the total citations accumulated per year (

TC per Year). This visualization highlights both the volume and persistence of research output across nearly two decades (2005–2024), offering a dynamic perspective on the continuity and influence of the field’s most prolific contributors.

The results indicate that authors such as ZHANG Y., LI Y., LIU Y., WANG Y., and KIM S. have maintained a sustained and upward trajectory in publication productivity since approximately 2015, with notable acceleration after 2018. Their citation intensity (darker circles) increased significantly during the 2019–2023 period, coinciding with the consolidation of deep learning, neural networks, and optimization techniques as dominant AI research paradigms. This pattern reflects cumulative expertise, in which early contributions provided a foundation for ongoing influence and high visibility in subsequent years. Other researchers, including LI J., WANG J., and ZHANG J., exhibit steady productivity with slightly lower citation density, suggesting a consistent but less concentrated impact compared to the top-tier group. Nonetheless, their longitudinal activity denotes methodological specialization and strong participation in multi-author collaborations, an essential feature of AI’s interdisciplinary ecosystem.

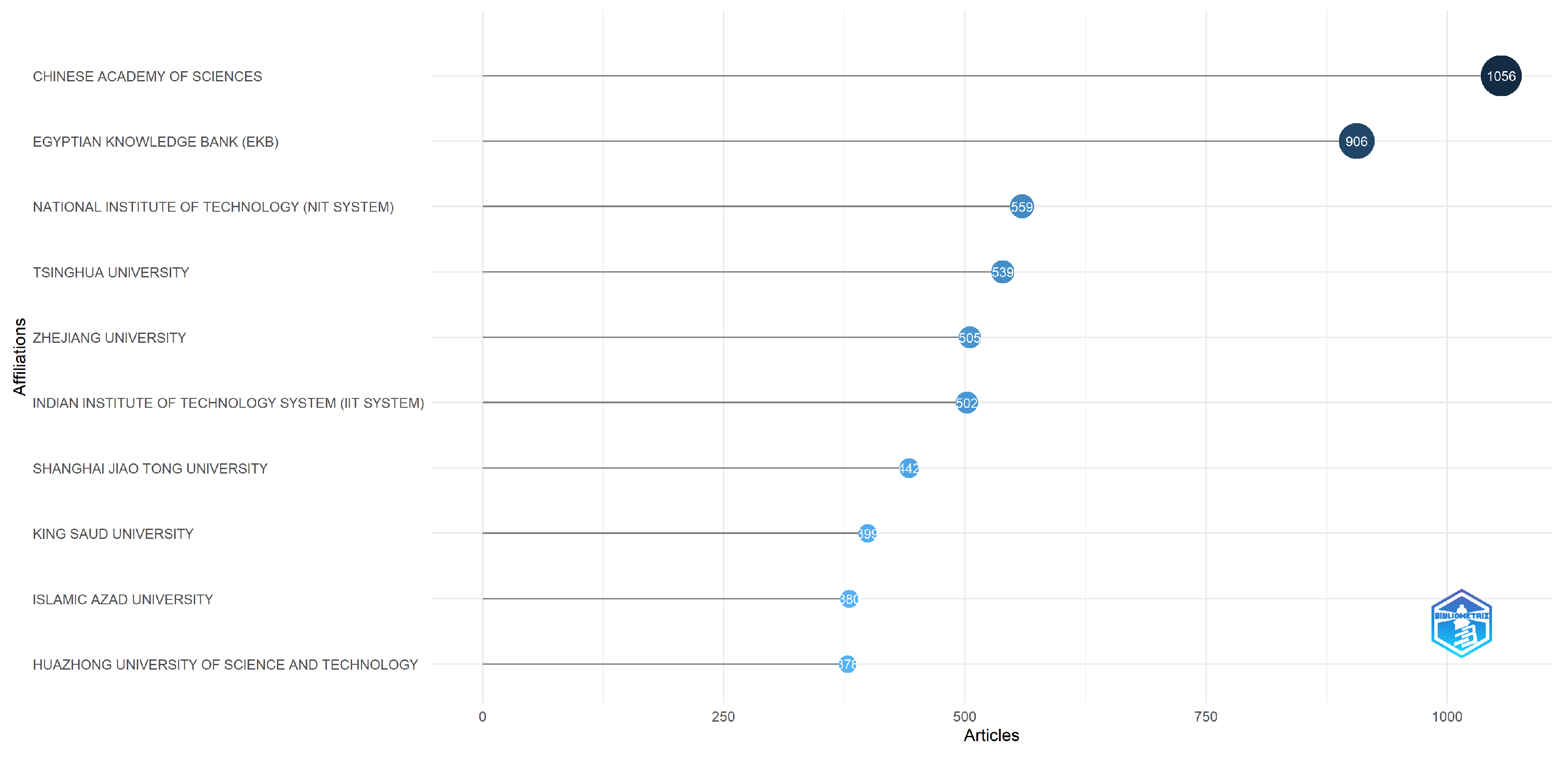

The collective output of these authors demonstrates a concentration of intellectual leadership largely within Chinese and East Asian institutions, reinforcing the findings in

Table 2, where China emerges as the global leader in both research volume and citation performance. Moreover, the absence of major geographic gaps across the timeline suggests continuous engagement rather than episodic contributions, confirming the sustained expansion of the AI research community over time.

In summary,

Figure 3 show a robust pattern of cumulative productivity, where experienced authors consistently contribute to the advancement of Artificial Intelligence through iterative refinement of methods and diversification of applications.

This trajectory underscores the growing institutional maturity and strategic investment in AI research observed over the last decade.

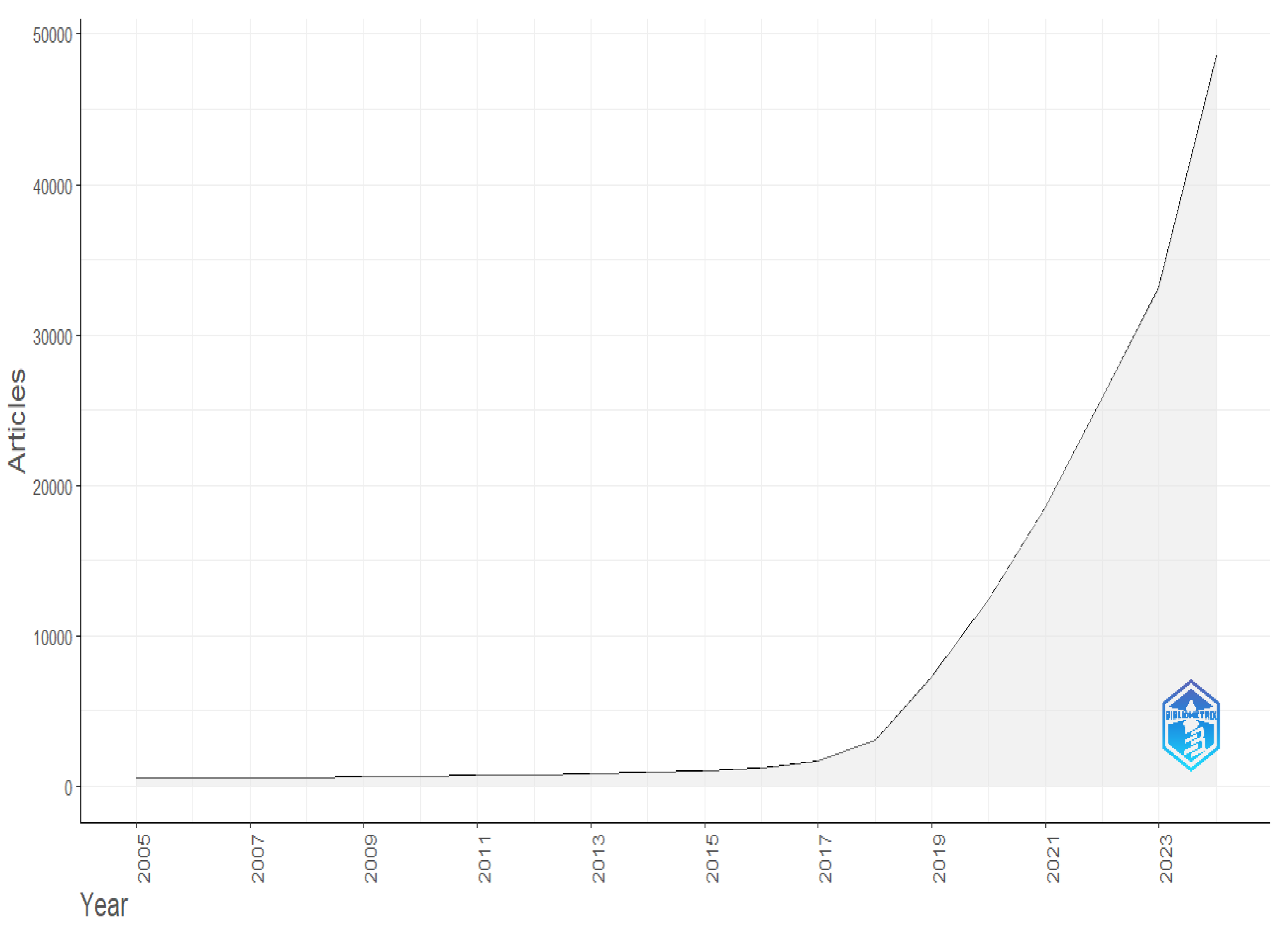

Figure 4 show the temporal evolution of Artificial Intelligence (AI) publications from 2005 to 2024. The curve exhibited a clear exponential growth pattern, with three distinguishable phases of development. During the first phase (2005–2015), the research output remained relatively modest, reflecting the formative years of modern AI dominated by theoretical and algorithmic exploration. A moderate increase began around 2015, coinciding with the resurgence of neural networks and consolidation of deep learning as a dominant paradigm.

A pronounced inflection point appeared between 2017 and 2018, marking the transition from steady growth to exponential expansion. This surge aligns with the democratization of high-performance computing resources, the emergence of open-source frameworks such as TensorFlow and PyTorch, and the rapid adoption of GPUs and cloud-based AI infrastructures. These technological enablers significantly lowered barriers to entry for experimentation and large-scale data processing.

From 2020 onward, the publication rate accelerates sharply, reaching its historical maximum by 2024. This period coincides with the proliferation of generative models, reinforcement learning applications, and the integration of AI into nearly all scientific and engineering domains. The cumulative pattern underscores AI’s transition from a specialized research topic to a pervasive scientific discipline driving innovation across sectors.

Overall, the figure reflects a sustained exponential trajectory, suggesting that AI-related publications will continue to expand in terms of volume and thematic diversity. This trend highlights not only the technological maturation of AI but also its growing role as a foundational component of modern scientific inquiry.