Submitted:

22 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

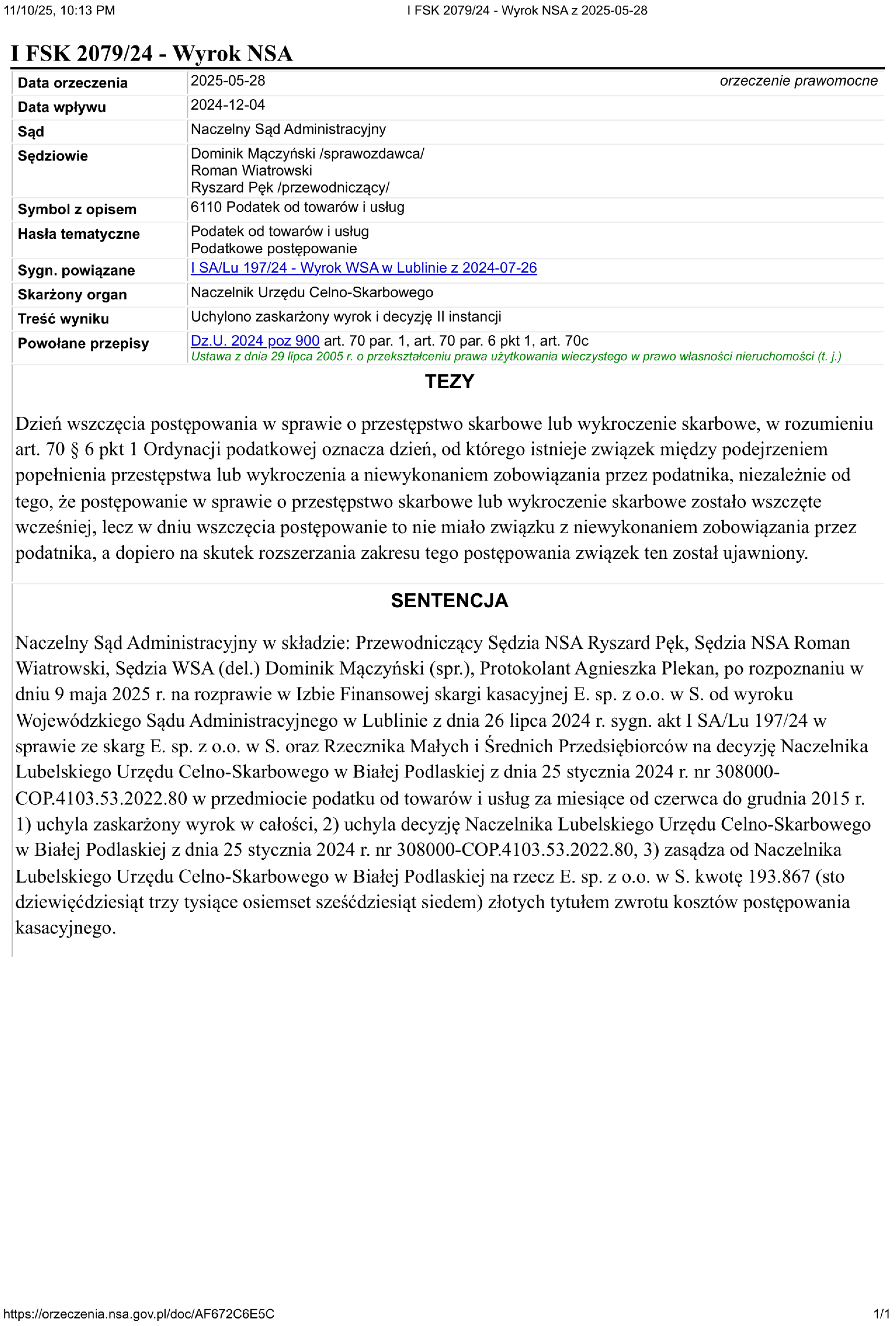

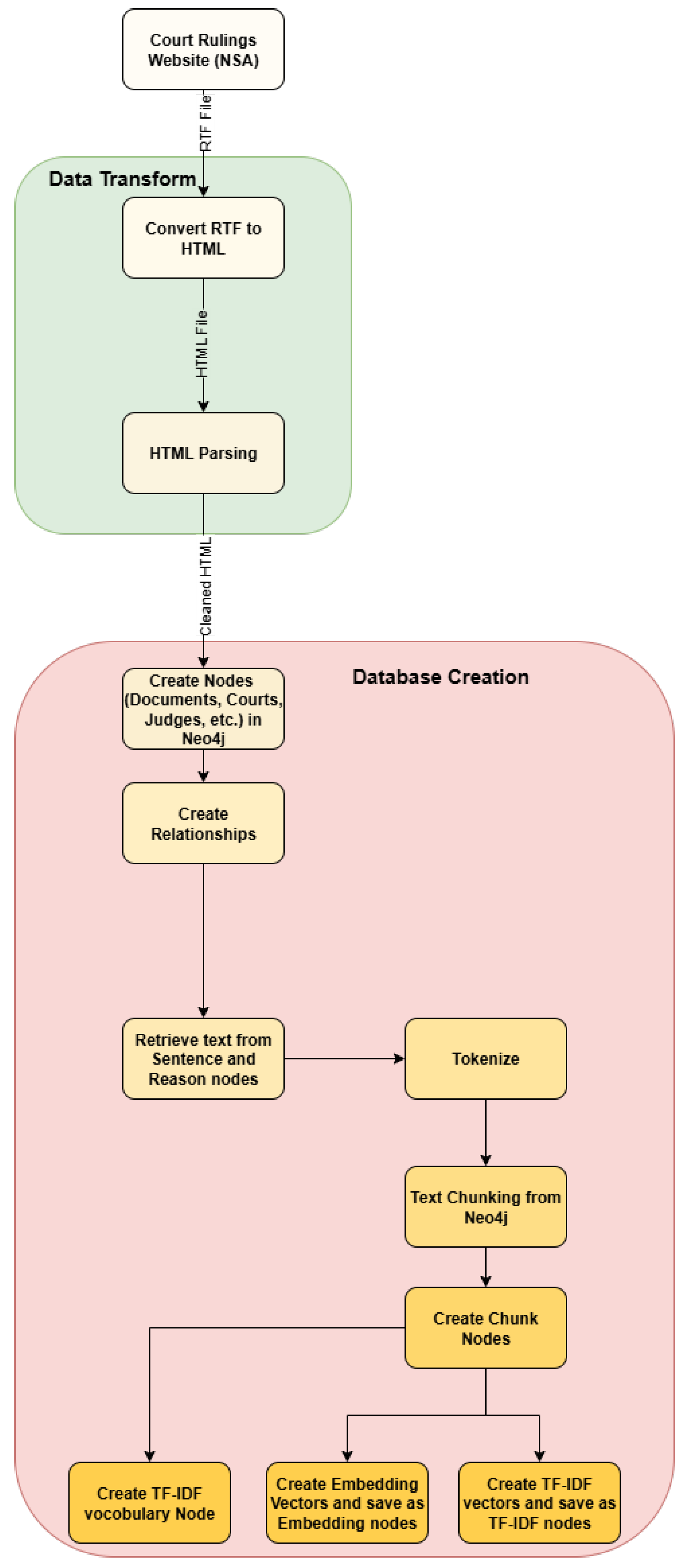

2. Building the LEGRA Knowledge Graph

2.1. Data Sources and Legal Context

2.2. Graph Modeling: Entities and Relationships

2.3. Processing Pipeline

Ingesting Data

Cleaning and Structuring

Parsing Metadata and Relations

Chunking and Indexing

Compliance and Versioning

2.4. Example Case: A Judgment’s Journey

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Hardware

- Processor: 12th Gen Intel Core i7-12700H (14 cores/20 threads, 2.3–4.7 GHz)

- RAM: 16 GB (15.6 GB available)

- System: 64-bit Windows OS, x64 architecture

- ML Acceleration: CPU only, no GPU utilized

3.2. Pipeline Throughput and Storage Efficiency

| Data Type | Mean Size per Doc [KB] | Removable? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input RTF | 16 | Yes | Downloaded, parsed then disposable |

| Intermediate HTML | 5.3 | Yes | Temporary conversion file |

| Persistent Graph (Neo4j) | 39 | No | Net increase in DB after batch import |

| Total/document | 60.3 | Input/int. removable | 15 runs, 50 docs each |

| Neo4j Baseline | 516,000 | No | Pre-allocated graph logs/schema |

| Pipeline Stage | Mean Time [s] | Variance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTF Download | 1.74 | High | Strongly dependent on internet speed |

| RTF→HTML Convert | 0.12 | Very low | Stable, local CPU operation |

| HTML Parse+Import | 0.11 | Low | Fast parsing, structure-dependent |

| Chunking/Indexing | 1.61 | Moderate | Can be accelerated with GPU |

| Total/document | 3.6 | – | Across n=15, 50-document batches |

3.3. Processing Time per Pipeline Stage

3.4. Metadata Generation and Graph Data Model

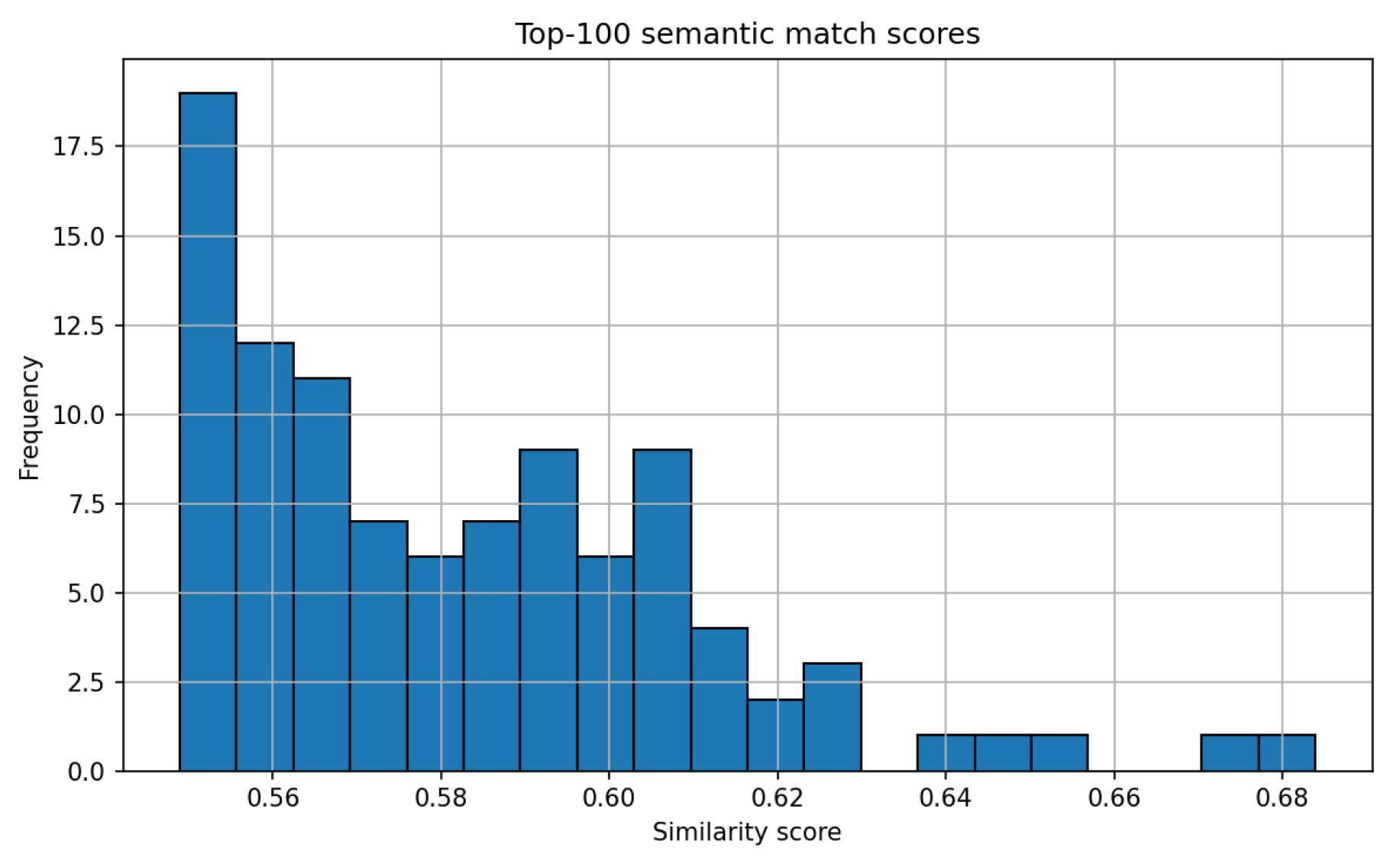

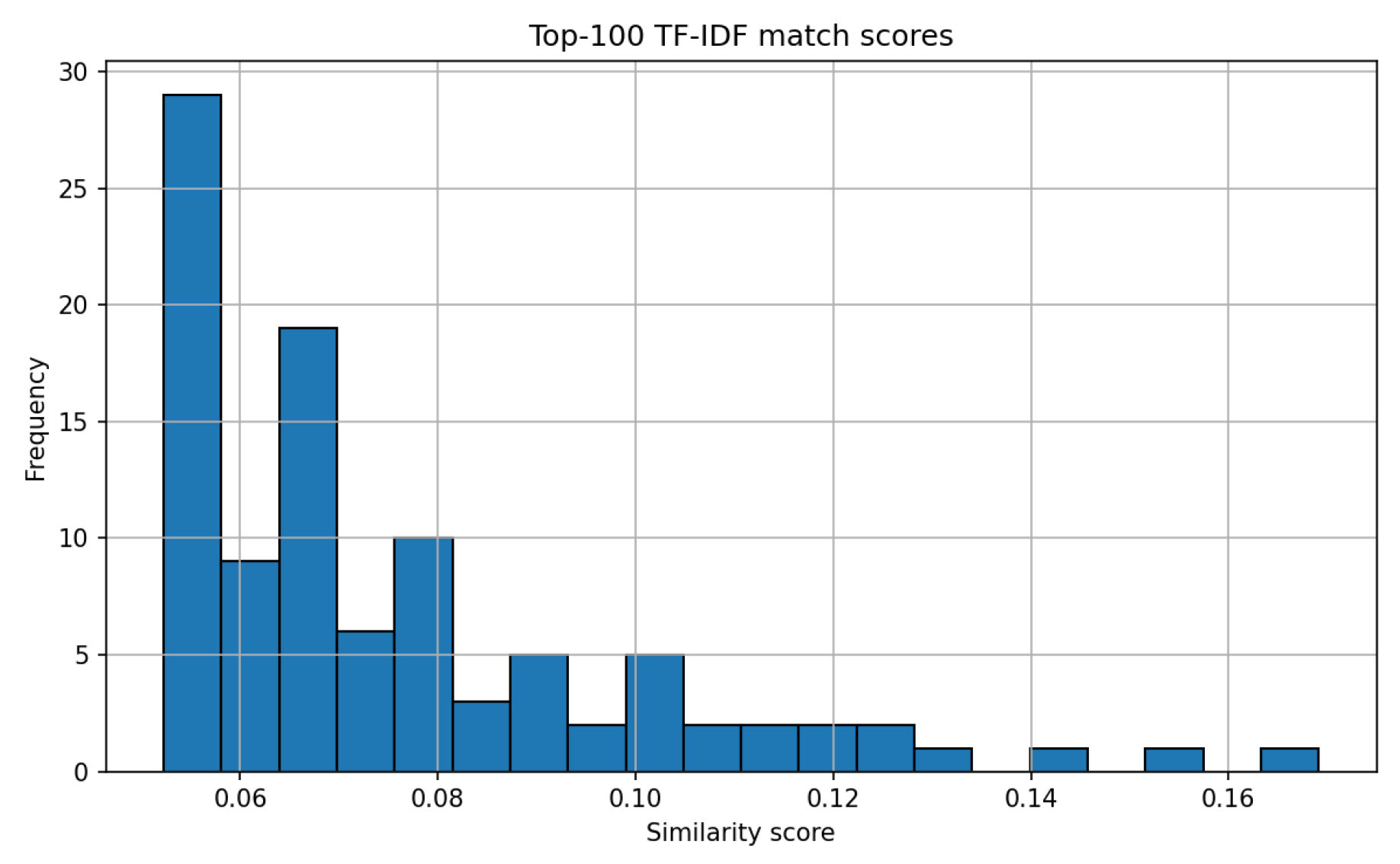

3.5. Chunking, Indexing, and Retrieval Performance

3.5.1. Chunking and Indexing

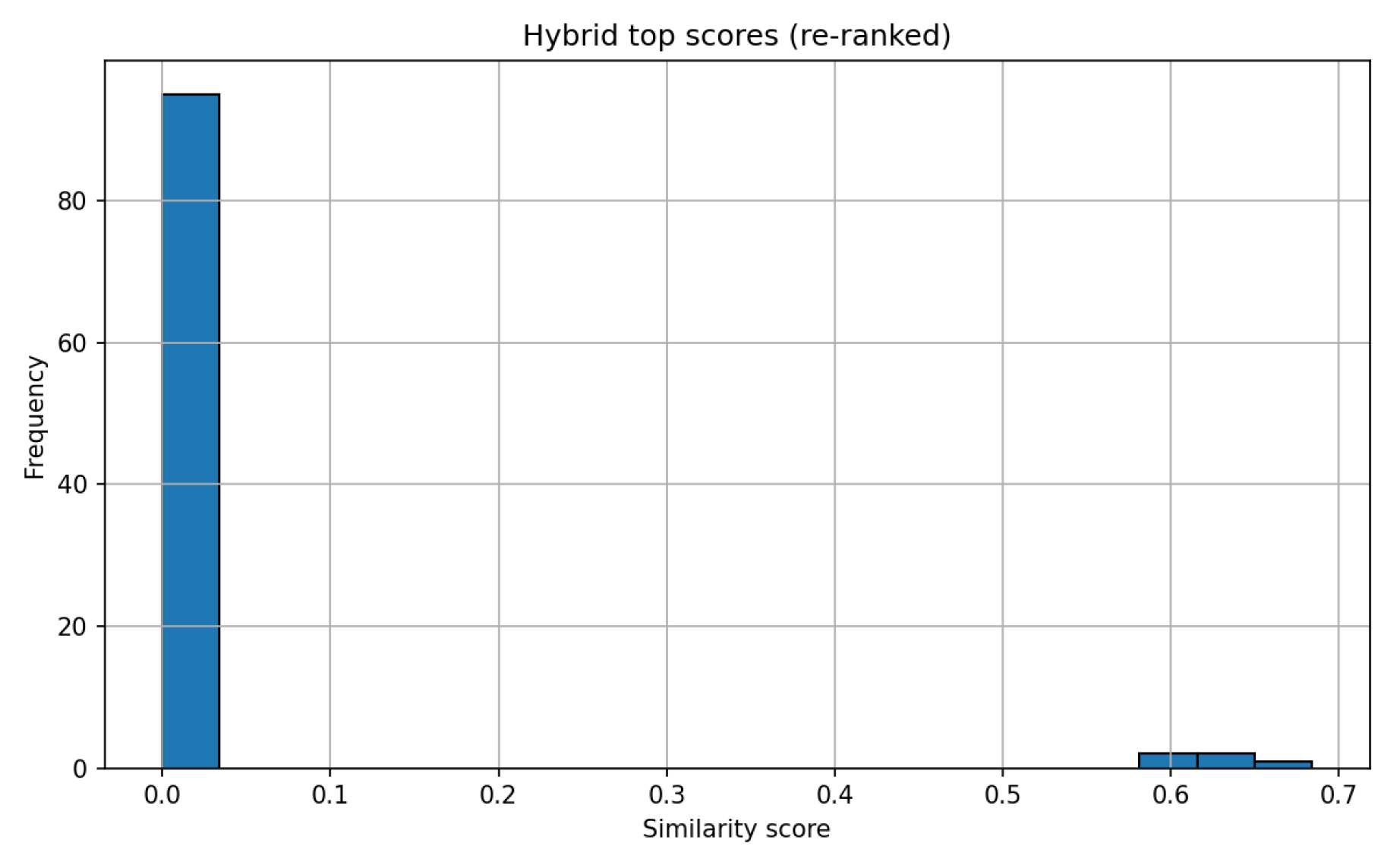

3.5.2. Retrieval Performance

-

“Jaka była kwota zasądzona przez Wojewódzki Sąd Administracyjny w Gliwicach na rzecz strony skarżącej w sprawie ze skargi F. sp. z o.o. w W.?”(“What amount was awarded by the Administrative Court in Gliwice to the complaining party in the case involving F. Ltd. from W.?”)For this query, the relevant judgment (ID: II SA/Gl 636/25) was retrieved at the top of the result list in all tested scenarios, demonstrating the robustness of the hybrid approach.

3.6. Graph Versus SQL Databases: Query Power and Design Rationale

3.7. Scalability, Operational Notes, and Best Practices

- Neo4j’s 516 MB baseline is a fixed overhead; actual graph database growth per document is 39 KB.

- All temporary files can be deleted after graph construction, allowing LEGRA to efficiently manage very large corpora.

- Overall memory usage remains well within 16 GB even at tested batch sizes; GPU/parallelization can raise future throughput ceiling.

- Both disk and runtime are, however, variable network and local CPU/GPU being the principal moderating factors.

3.8. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of Graph Databases for Legal Retrieval

4.2. Hybrid Retrieval Mechanism

4.3. Scalability and Performance Challenges

4.4. Limitations of Multilingual Embeddings

4.5. Future Directions

References

- Malve, A.; Chawan, P. A Comparative Study of Keyword and Semantic based Search Engine. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Bao, Z.; Lee, M.L.; Ling, T.W. A Semantic Approach to Keyword Search over Relational Databases 2013. pp. 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Tahura, U.; Selvadurai, N. The use of artificial intelligence in judicial decision-making: The example of China. International Journal of Law, Ethics and Technology 2022, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watamura, E.; Liu, Y.; Ioku, T. Judges versus artificial intelligence in juror decision-making in criminal trials: Evidence from two pre-registered experiments. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0318486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, E.A.; Saran, S. Judge AI: Assessing Large Language Models in Judicial Decision-Making 2025. [CrossRef]

- Centralna Baza Orzeczeń Administracyjnych — orzeczenia.nsa.gov.pl. https://orzeczenia.nsa.gov.pl/cbo/query. [Accessed 18-10-2025].

- Ustawa z dnia 6 września 2001, r. o dostępie do informacji publicznej, 2001. Journal of Laws 2001 No. 112, item 1198. Consolidated version.

- Administracyjny, N.S. Wyrok NSA I FSK 2079/24 z dnia 28 maja 2025. Centralna Baza Orzeczeń Sądów Administracyjnych (CBOSA), 2025. Accessed 2025-11-14.

- Selenium Project. Selenium WebDriver, 2024. Version 4.35.

- E-iceblue Developers. Spire.Doc for Python, 2024. RTF/Word Document Conversion Library.

- Richardson, L. Beautiful Soup Documentation, 2023. Beautiful Soup 4.12 Documentation.

- Tokenizers — huggingface.co. https://huggingface.co/docs/tokenizers/index. [Accessed 19-11-2025].

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. TF-IDF Vectorizer (scikit-learn), 2024. scikit-learn v1.4.2.

- AI, N. nomic-ai/nomic-embed-text-v2-moe. https://huggingface.co/nomic-ai/nomic-embed-text-v2-moe, 2025. 475M parameters, 1.6B multilingual pairs (incl. 63M Polish), Mixture of Experts (MoE), Matryoshka representation learning, base model: FacebookAI/xlm-roberta-base, supports >40 languages.

- Nussbaum, Z.; Duderstadt, B. Training Sparse Mixture Of Experts Text Embedding Models. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docker Inc.. Docker: Accelerated Container Application Development, 2025. Version information and documentation available online.

- charliermarsh. uv — docs.astral.sh. https://docs.astral.sh/uv/.

- Python UV: The Ultimate Guide to the Fastest Python Package Manager — datacamp.com. https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/python-uv.

- uv: The Fastest Python Package Manager | DigitalOcean — digitalocean.com. https://www.digitalocean.com/community/conceptual-articles/uv-python-package-manager.

- Chan, D.M.; Rao, R.; Huang, F.; Canny, J.F. t-SNE-CUDA: GPU-Accelerated t-SNE and its Applications to Modern Data 2018. [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. Contextual Retrieval in AI Systems, 2024. Combining semantic and keyword search reduces retrieval failure rate by nearly half.

- Rathle, P. The GraphRAG Manifesto: Adding Knowledge to GenAI. Blog post on Neo4j website, 2024.

- Moghaddam, Z.Z.S.; Dehghani, Z.; Rani, M.; Aslansefat, K.; Mishra, B.K.; Kureshi, R.R.; Thakker, D. Explainable Knowledge Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation (KG-RAG) with KG-SMILE 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tiddi, I.; Schlobach, S. Knowledge graphs as tools for explainable machine learning: A survey. Artificial Intelligence 2022, 302, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polish Term | English Equivalent | Node Type | Presence/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Metadata | |||

| Sygnatura (id) | Case Identifier | :Dokument | Always |

| Typ | Judgment Type | :Dokument | Always |

| Data orzeczenia | Judgment Date | :Dokument | Always |

| Prawomocne | Final/Binding | :Dokument | Extracted from date line |

| Data wpływu | Filing Date | :Dokument | Optional |

| Institutions and Persons | |||

| Sąd | Court | :Sąd | Always |

| Sędziowie | Judges | :Sędzia | Always |

| Funkcja | Function | :Funkcja | If specified per judge |

| Parties and Authorities | |||

| Strony | Parties | :Dokument | Optional |

| Skarżony organ | Challenged Authority/Body | :Organ | Optional, multi |

| Pełnomocnik/Obrońca | Attorney/Representative | :Dokument | Rare (custom) |

| Classification | |||

| Symbol z opisem | Symbol (with description) | :Symbol | Optional |

| Hasła tematyczne | Thematic Keyword (Tag) | :Hasło | Optional |

| Legal Links | |||

| Sygn. powiązane | Related Case Signature | :Dokument + POWOŁUJE_SIĘ_NA | Optional |

| Powołane orzeczenia z tekstu | Case Citations (Text) | :Dokument + POWOŁUJE_SIĘ_NA | Auto-detected/NLP |

| Powołane przepisy | Referenced Legal Provisions | :Przepis | Optional, multi |

| Decision | |||

| Treść wyniku | Case Outcome/Result | :Wynik | Optional, multi |

| Judgment Text | |||

| Sentencja | Operative Sentence | :Sentencja | Always |

| Uzasadnienie | Justification/Reasoning | :Uzasadnienie | Optional |

| Tezy | Legal Principles/Theses | :Teza | Rare |

| Zdanie odrębne | Dissenting Opinion | :ZdanieOdrebne | Rare |

| Inne pola | Custom Fields | JSON in :Dokument.dodatkowe_dane | Dynamic |

| Retrieval & Indexing | |||

| Chunk | Text Chunk | :Chunk | Generated from texts |

| Embedding | Dense Vector Embedding | :Embedding | Optional |

| TF-IDF | TF-IDF Vector | :TFIDF | Always |

| Vocabulary | TF-IDF Vocabulary | :TFIDF_Vocabulary | Model meta |

| Relation | From → To | Purpose/Description |

|---|---|---|

| [:WYDAŁ] | Sąd→Dokument | Court issued judgment |

| [:BRAŁ_UDZIAŁ] | Sędzia→Dokument | Judge participated |

| [:PEŁNI_FUNKCJĘ] | Sędzia→Funkcja | Judicial role assignment |

| [:DOTYCZY] | Dokument→Organ | Judgment concerns authority |

| [:ZAWIERA_SYMBOL] | Dokument→Symbol | Legal classification |

| [:ZAWIERA_HASLO] | Dokument→Hasło | Thematic tag/data category |

| [:ZAKOŃCZONY] | Dokument→Wynik | Final result link |

| [:POWOŁUJE_PRZEPIS] | Dokument→Przepis | Cites legal provision |

| [:MA_SENTENCJĘ] | Dokument→Sentencja | Sentence section link |

| [:MA_UZASADNIENIE] | Dokument→Uzasadnienie | Reasoning section link |

| [:MA_TEZY] | Dokument→Teza | Legal principle link |

| [:MA_ZDANIE_ODREBNE] | Dokument→ZdanieOdrebne | Dissenting opinion |

| [:POWOŁUJE_SIĘ_NA] | Dokument→Dokument | Precedent/related case |

| [:MA_CHUNK] | Dokument→Chunk | Chunked text section |

| [:MA_EMBEDDING] | Chunk→Embedding | Embedding for search |

| [:MA_TFIDF] | Chunk→TFIDF | TF-IDF representation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).