Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

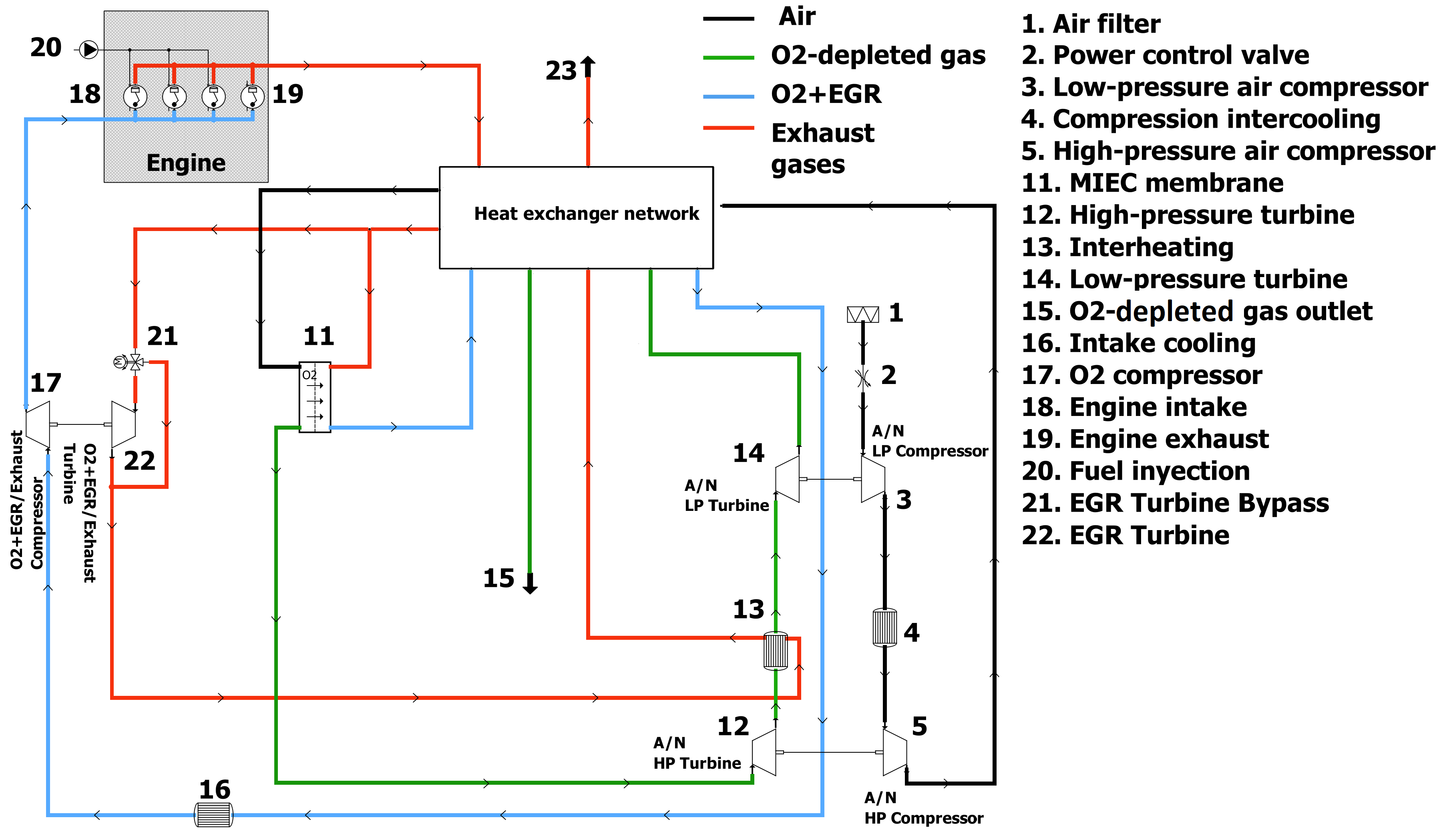

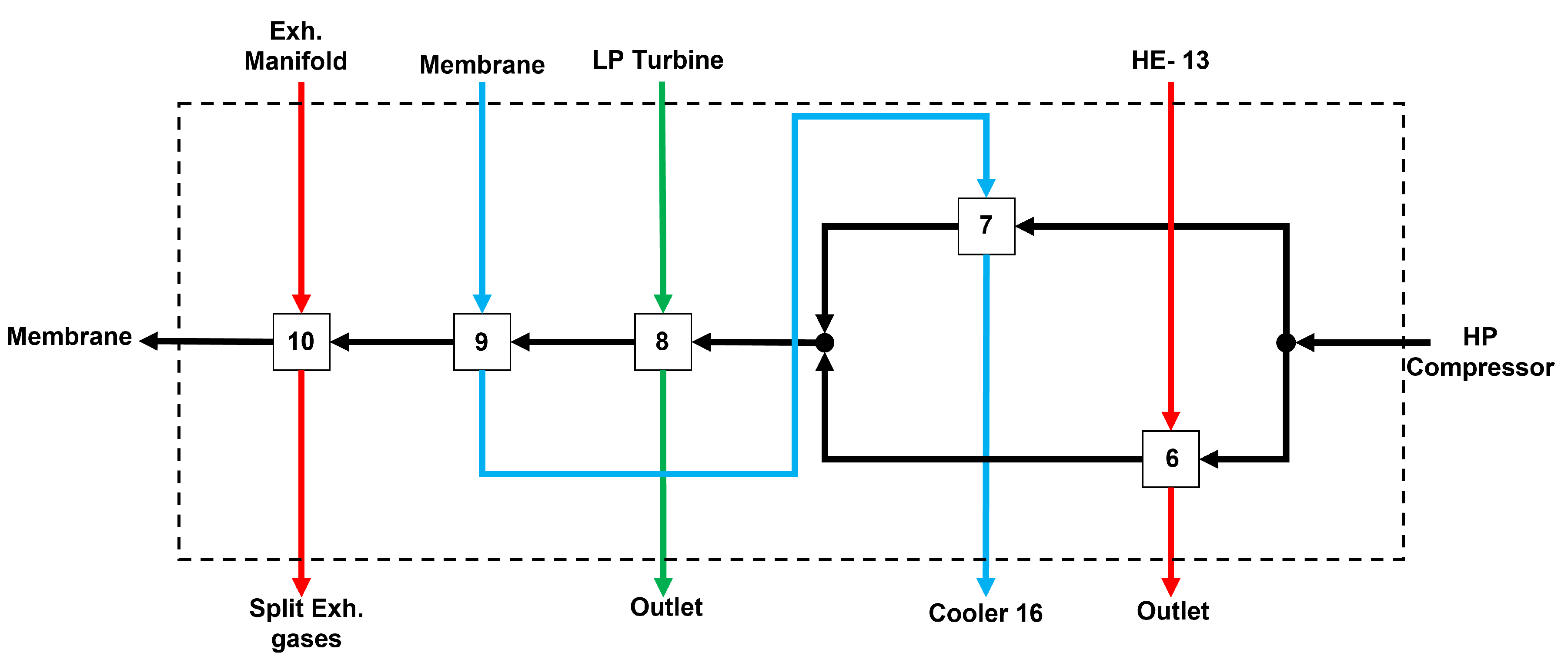

2. System Description

3. Methodology

3.1. Engine Specification and Benchmarking

3.2. Considerations, Variables, and Indicators for Performance Evaluation

- To achieve optimal conditions for membrane operation during air heating, a constant heat exchanger effectiveness of 95 is assumed, based on results by Komminos and Rodgakis [24].

- The intercooler between the air-driven compressors is assumed to have an outlet temperature of 25 °C.

- Mechanical losses are estimated by considering the energy consumption of auxiliary elements.

- The air composition is assumed to be 77 N2 and 23 O2 by mass fraction.

3.3. Turbochargers Scaling, Volumetric Engine´s Compression-Ratio, Limits and Baseline Statement

3.4. Part-Load Operation and Performance Indicators

4. Results and Discussion

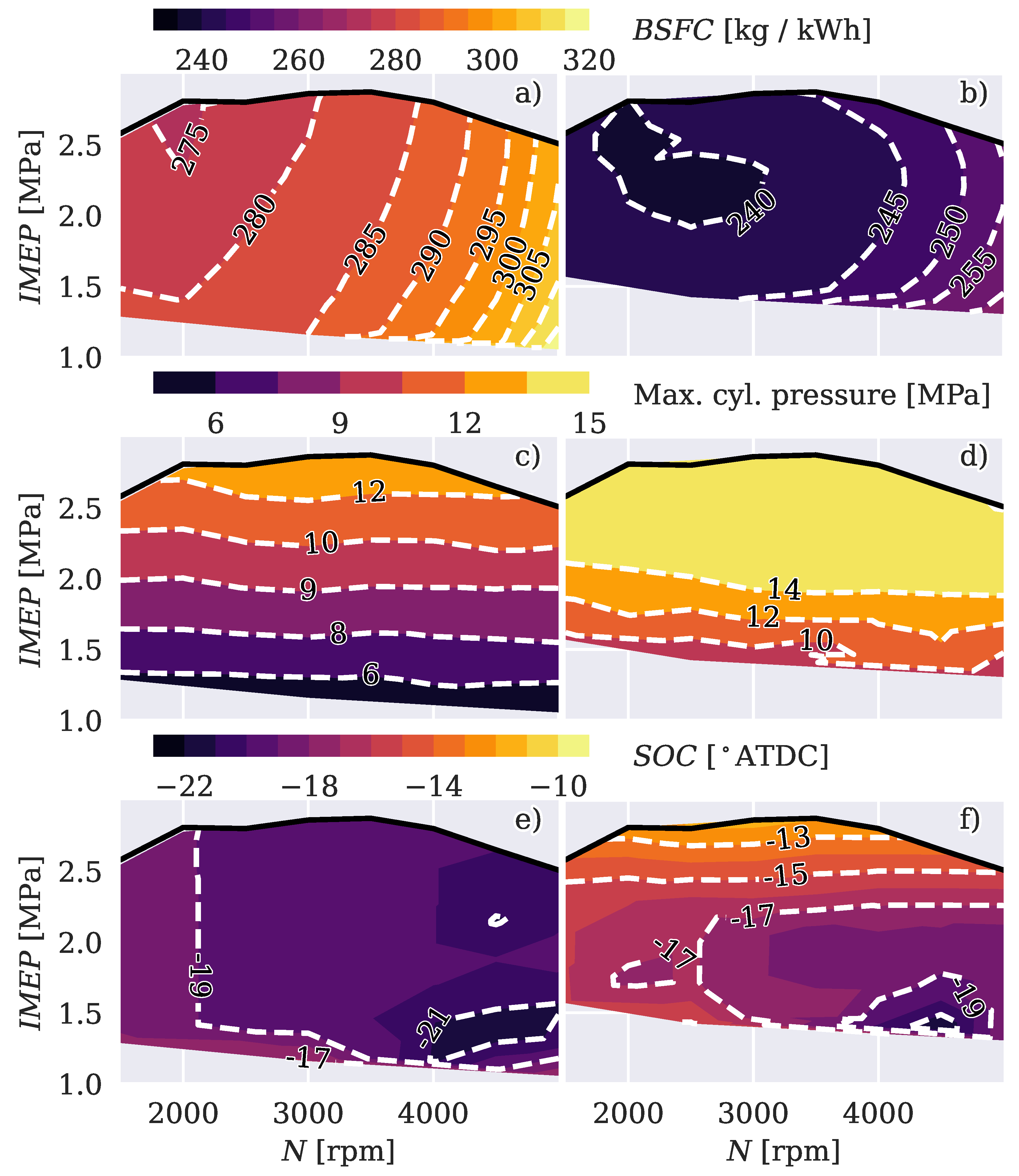

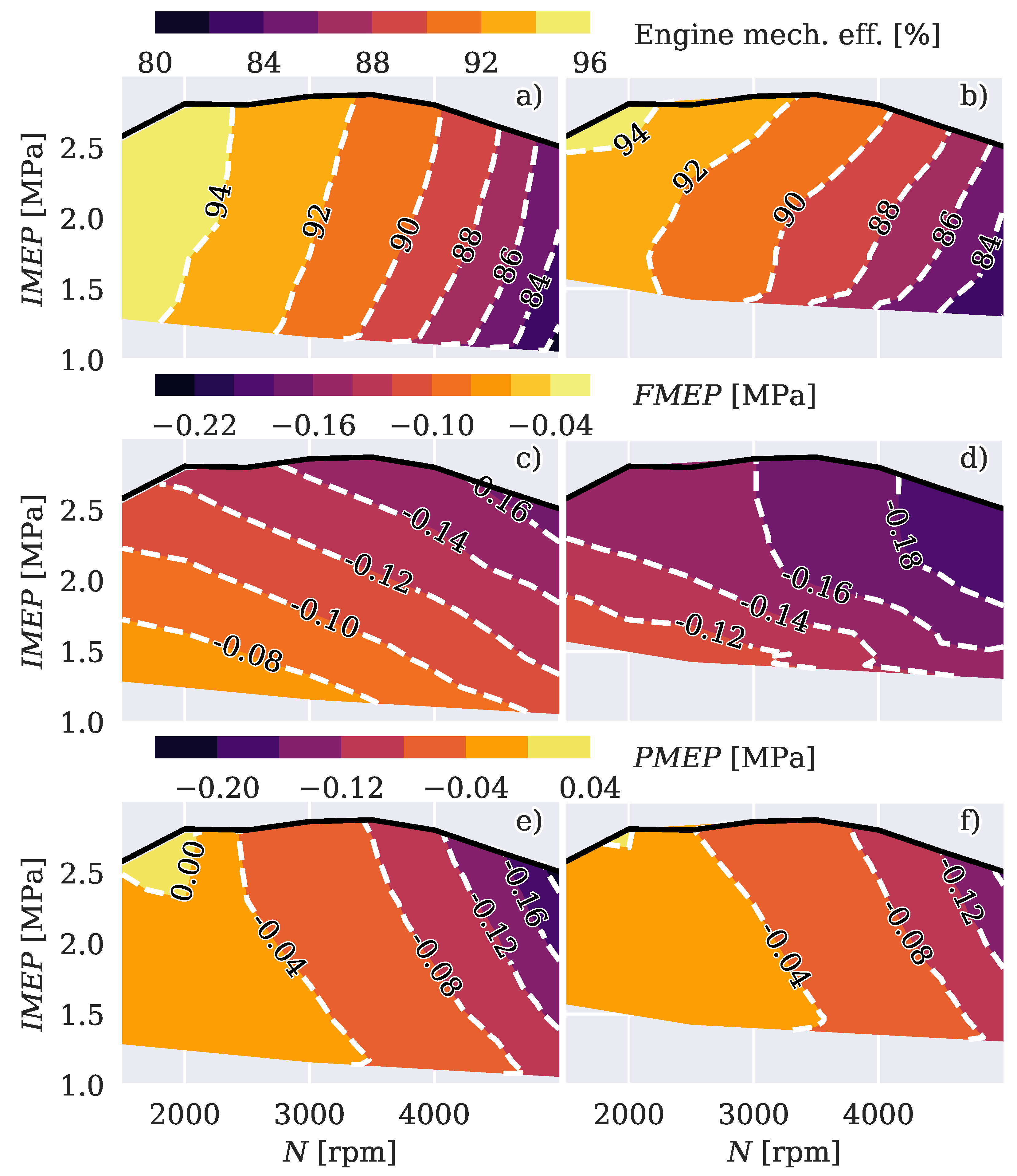

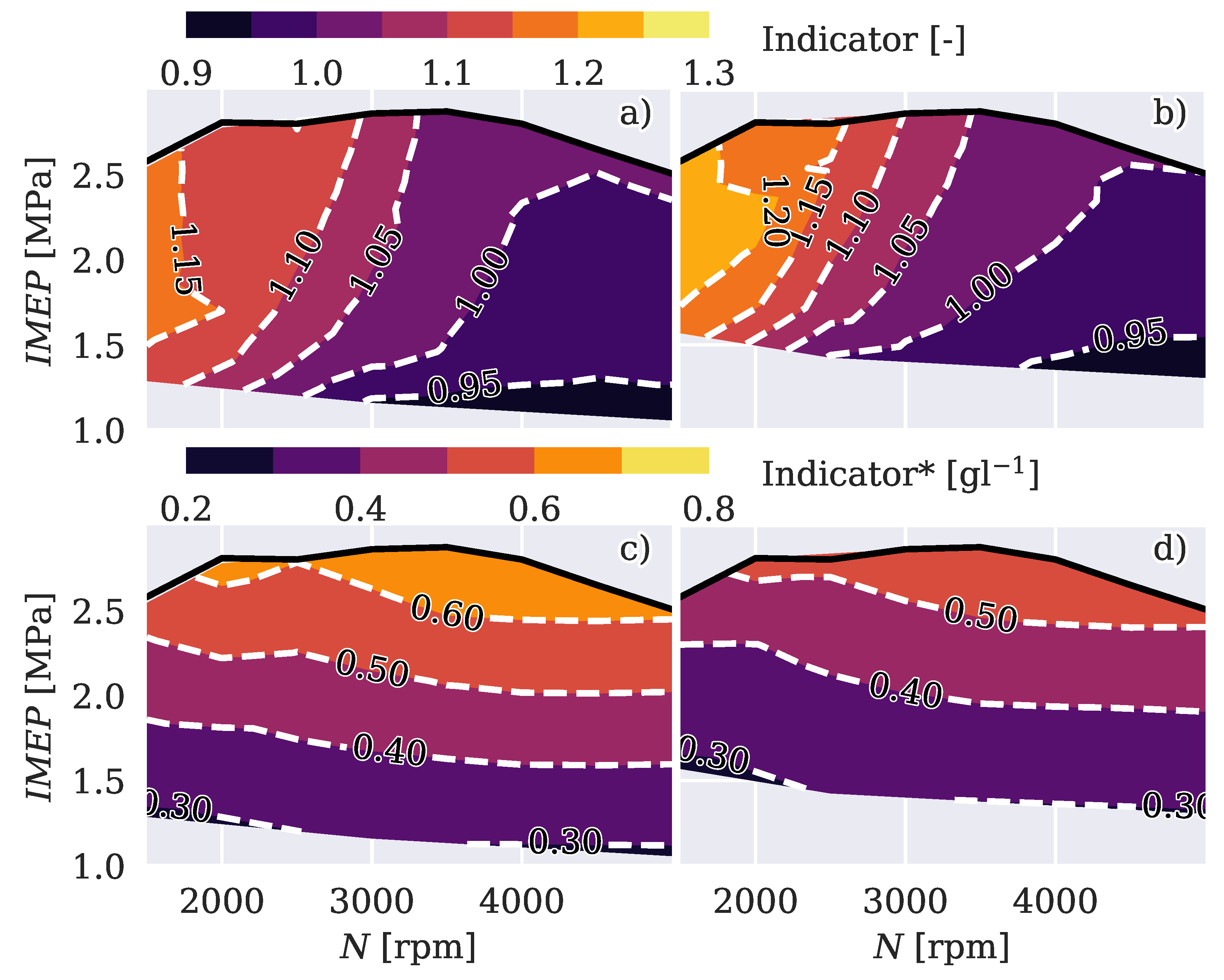

4.1. Part Load

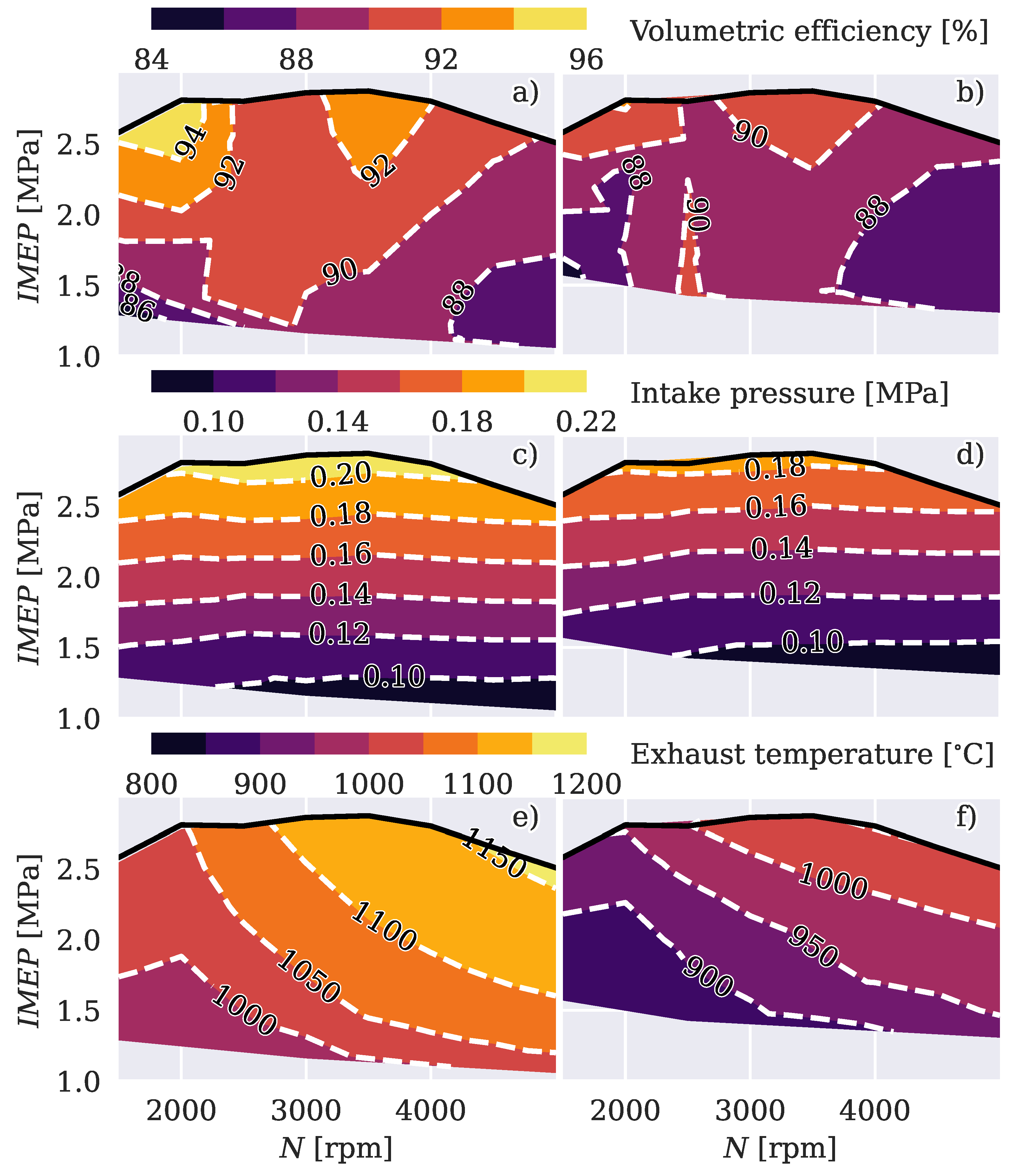

4.1.1. Engine

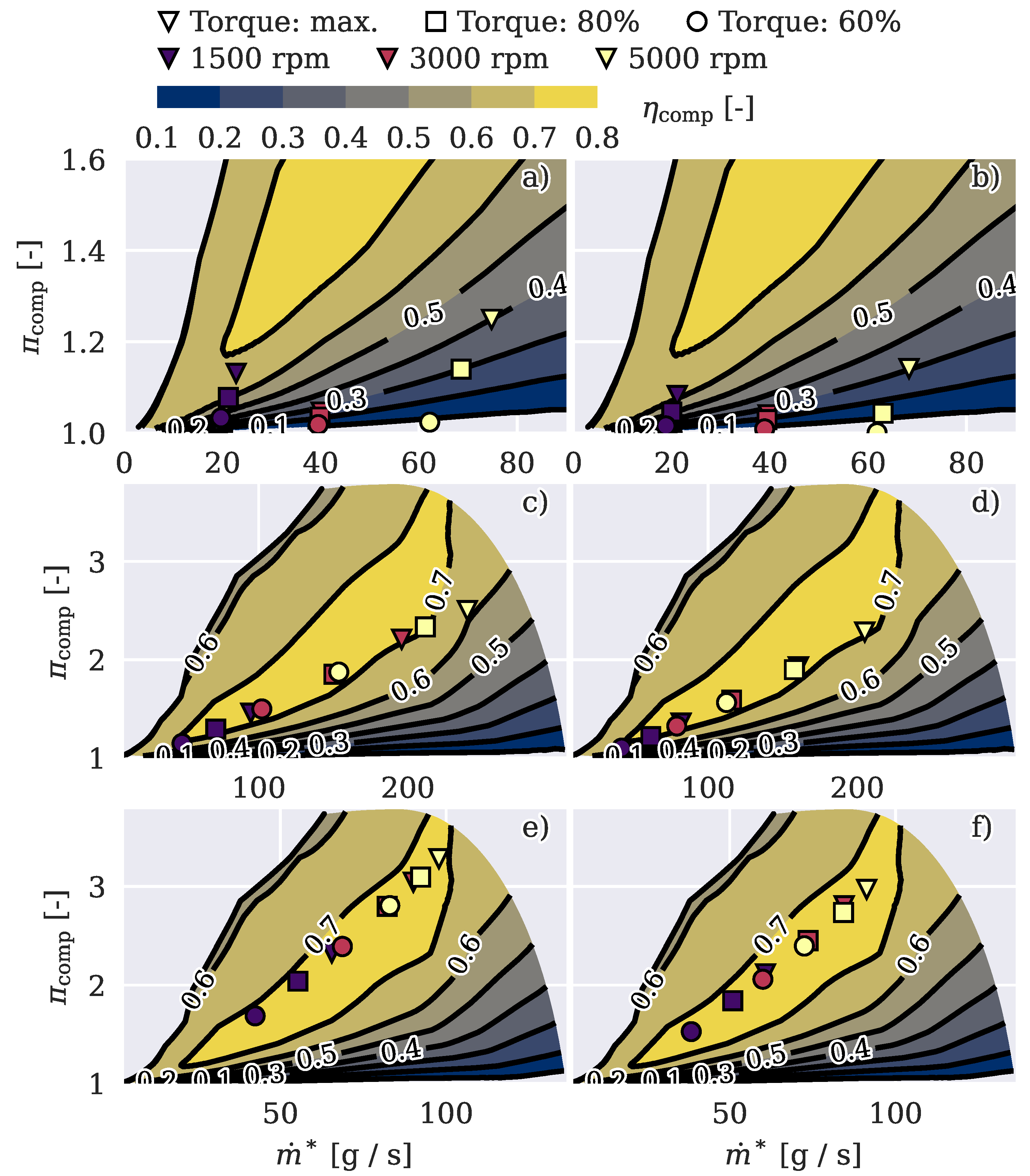

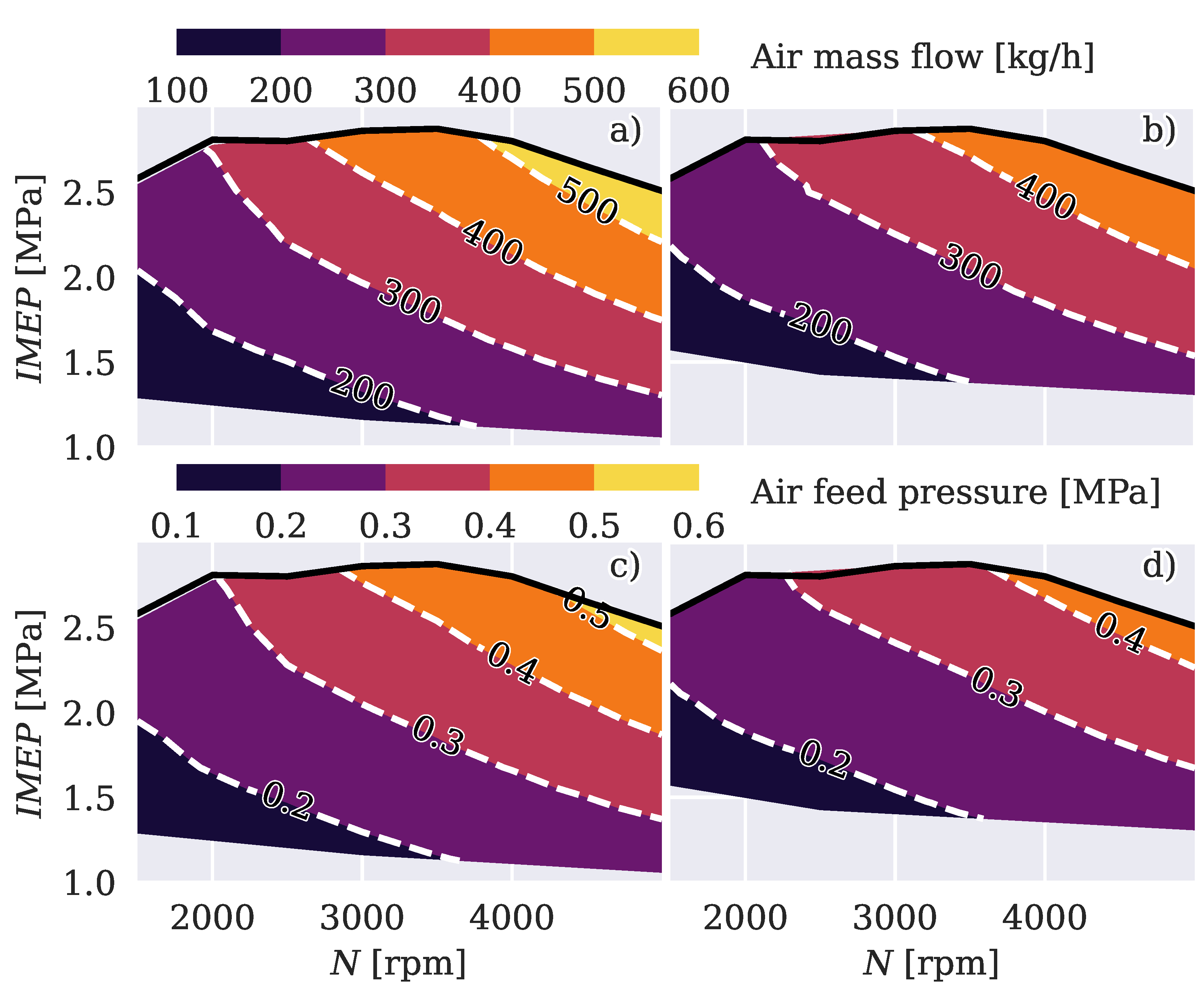

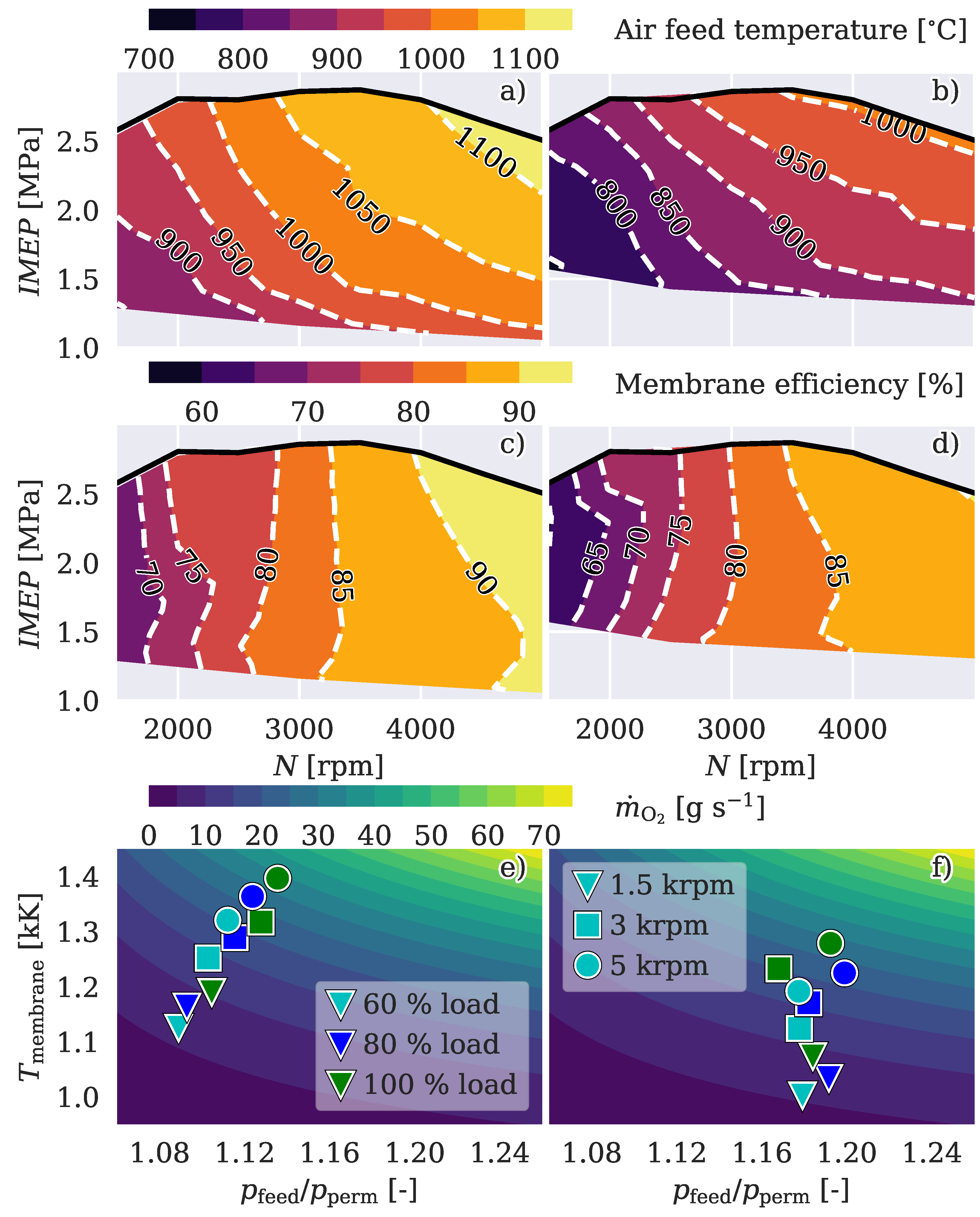

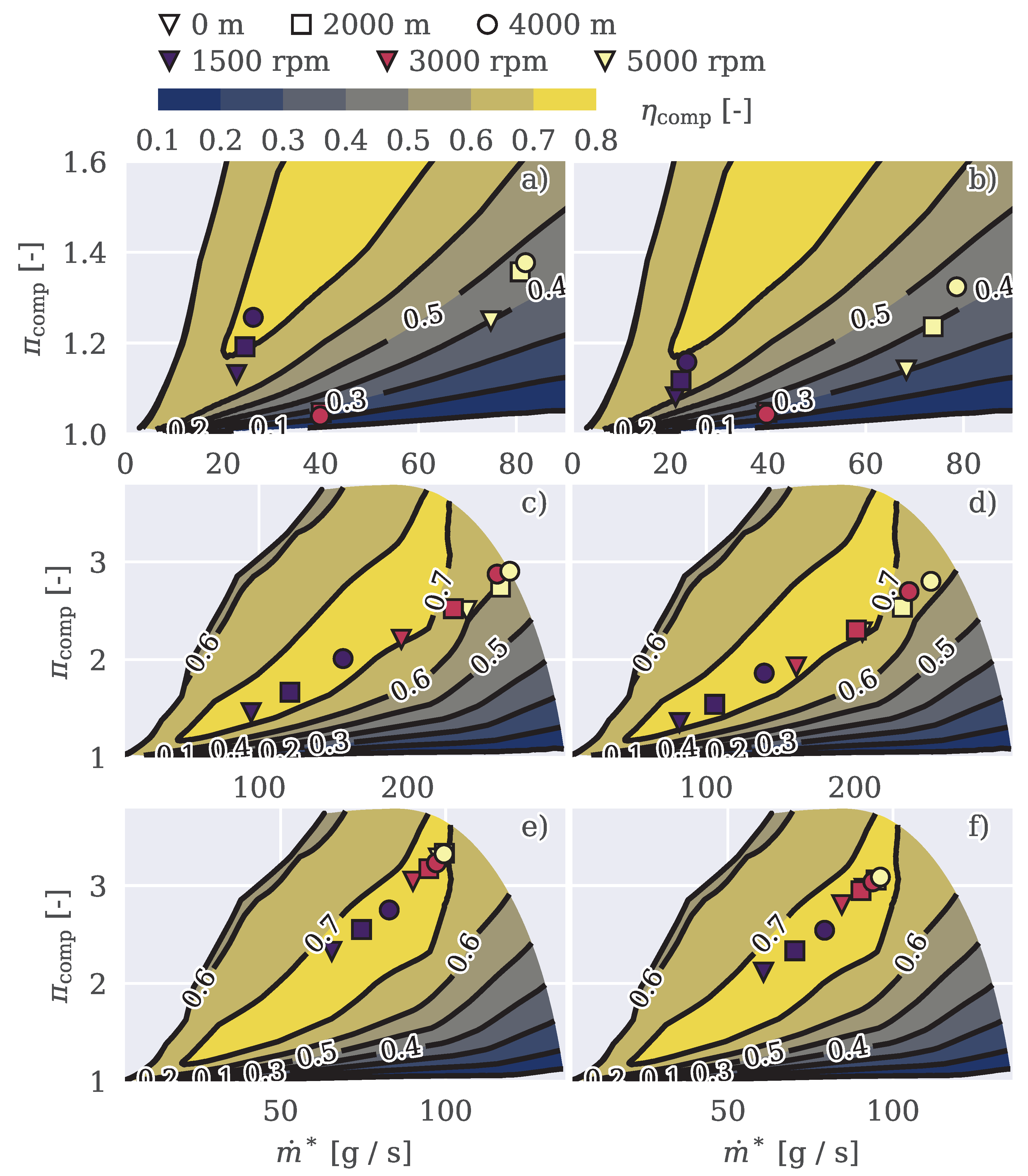

4.1.2. Oxygen Production Cycle

4.1.3. Limits Evaluation

- Adding an energy source, such as a heater or an electric compressor: This requires the addition of weight and volume to the system, as well as an increment in energy consumption.

- Increase the membrane area: The engine studies were made using a membrane area of 100 m2, selected after a trade-off decision at full load between membrane size and oxygen production enhancement. Increasing the membrane area enhances air separation, but also increases the system size, which can be detrimental in the transport context.

- Varying the settings of the VGTs: This action increases the air pressure, promoting oxygen production. But reduce net air flow and net power, what is not an issue at part loads. Also penalises efficiency since turbomachinery operates at off-design conditions.

- Delaying the combustion: This reduces engine efficiency while increasing exhaust temperature, thus decreasing the available energy for oxygen production, as seen in [28].

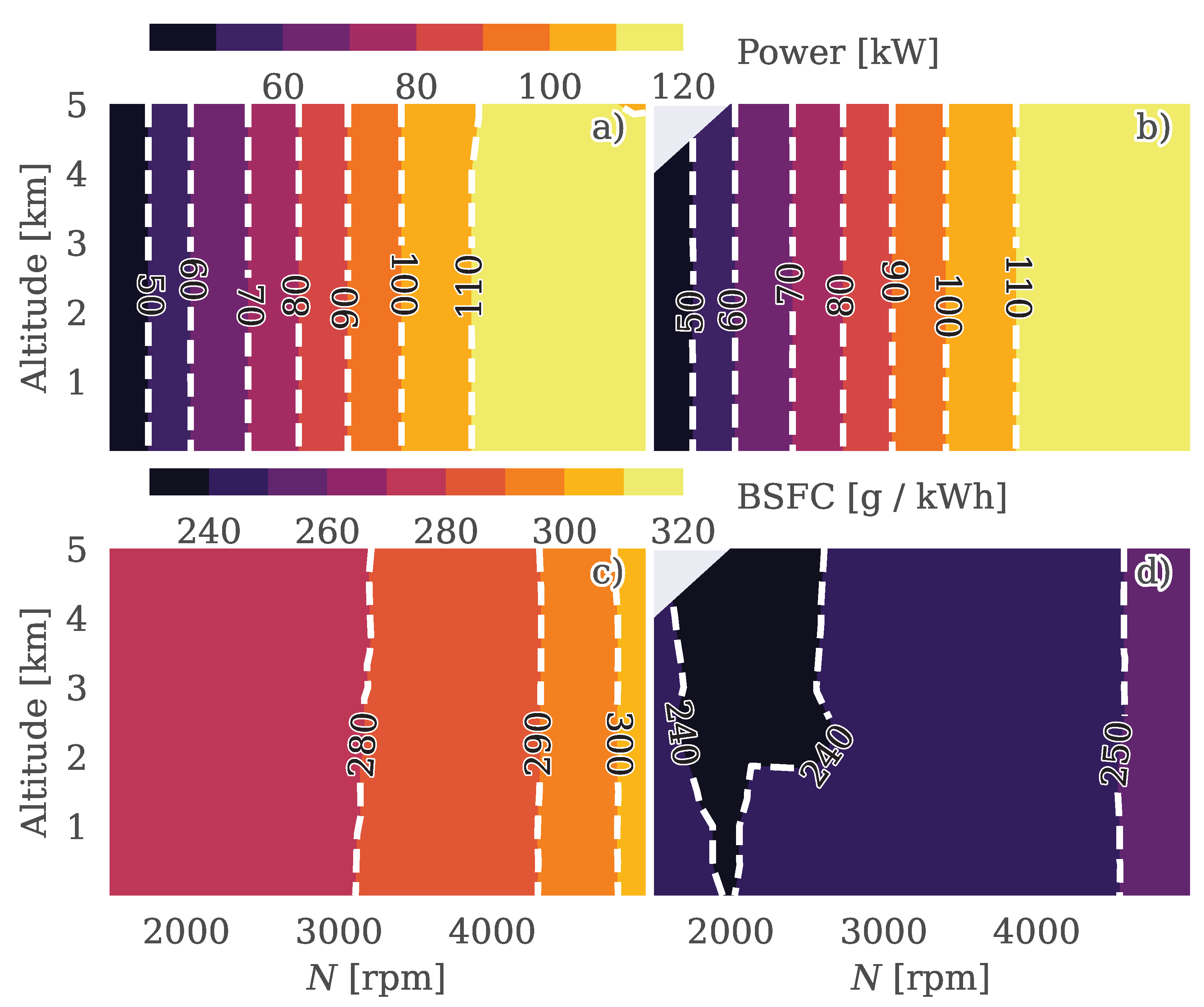

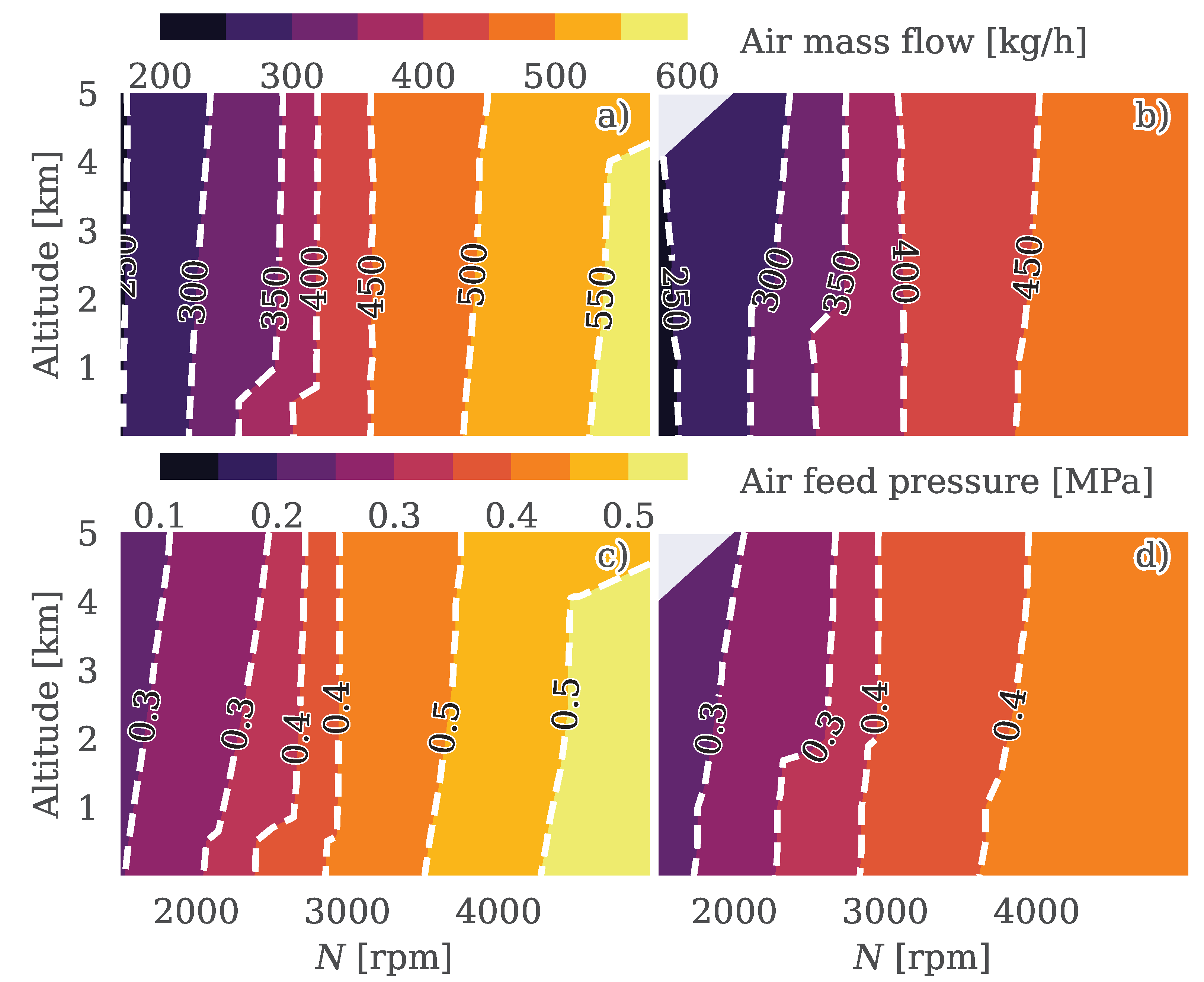

4.2. Altitude

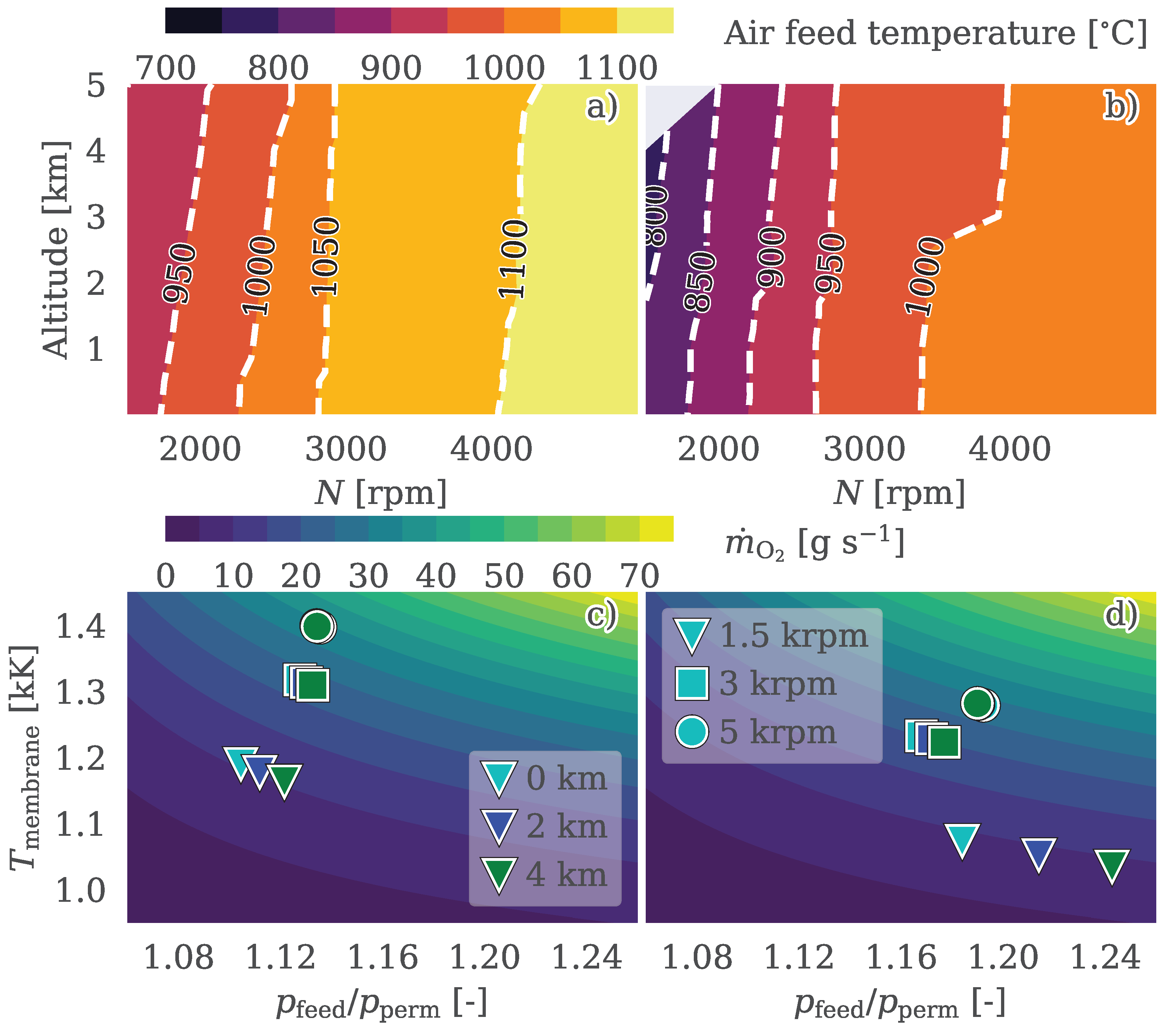

4.2.1. Engine

4.2.2. Oxygen Production Cycle

5. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATDC | After top dead centre |

| BSFC | Brake specific fuel consumption |

| BP | Brake Power |

| CAS | Cryogenic air separation |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CI | Compression-ignition engine |

| CR | Engine compression ratio |

| EGR | Exhaust gas recirculation |

| Efficiency | |

| Membrane efficiency | |

| Specific heat ratio | |

| HE | Heat exchanger |

| HP | High pressure |

| Energy required to meet MIEC conditions | |

| Air enthalpy flow at atmospheric conditions | |

| Enthalpy flow at the feed inlet | |

| ICE | Internal combustion engine |

| IMEP | Indicated mean effective pressure |

| Oxidizer-fuel equivalence ratio | |

| LP | Low pressure |

| MIEC | Mixed ionic and electronic conducting |

| Turbomachines nondimensional mass flow | |

| Air mass flow | |

| O2 mass flow permeated through the membrane | |

| Compressor corrected mass flow | |

| Compressor corrected speed | |

| OFC | Oxy-fuel combustion |

| Turbomachines nondimensional speed | |

| Compressor total-to-total pressure ratio | |

| Pressure of the membrane feed flow | |

| Pressure of exhaust manifold | |

| Pressure of intake manifold | |

| Temperature of intake manifold | |

| PMEP | Pumping Mean Effective Pressure |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| Average O2 partial pressure of the membrane feed flow | |

| Average O2 partial pressure of the membrane permeate flow | |

| Heat power dissipated by the intercooler | |

| SI | Spark-ignition engine |

| SOC | Start of combustion |

| Temperature of exhaust manifold | |

| Temperature of the membrane feed flow | |

| Temperature of intake manifold | |

| Maximum in-cylinder temperature | |

| Total engine displacement | |

| VGT | Variable Geometry Turbine |

| Power |

References

- European Union, 2021. 2030 climate & energy framework.

- European Union, 2016. Paris agreement.

- European Union, 2022. Commission proposes new euro 7 standards to reduce pollutant emissions from vehicles and improve air quality.

- Habib, M. A., Nemitallah, M., and Ben-Mansour, R., 2013. “Recent development in oxy-combustion technology and its applications to gas turbine combustors and ITM reactors”. Energy & Fuels,27(1), pp. 2–19. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C., and Liu, Z., 2018. Oxy-Fuel Combustion Fundamentals, Theory and Practice. Academic Press.

- Nema, A., Kumar, A., and Warudkar, V., 2025 “An in-depth critical review of different carbon capture techniques: Assessing their effectiveness and role in reducing climate change emissions”. Energy Conversion and Management,323, 119244. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F., Sun, H., Zhang, T., Wang, Q., Li, Y., Liao, H., Wu, X., and Liu, Z., 2024 “Comparative study on process simulation and performance analysis in two pressurized oxy-fuel combustion power plants for carbon capture”. Energy Conversion and Management,303, 118178. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Yu, X., Fu, L.-Z., Deng, J., Hu, Z., and Li, L.-G., 2014. “A high efficiency oxyfuel internal combustion engine cycle with water direct injection for waste heat recovery”. Energy,70(1), pp. 110–120. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z., Wu, Z., Zhang, Z., Deng, J., Hu, Z., and Li, L., 2017. “Study of the Combustion Characteristics of a HCCI Engine Coupled with Oxy-Fuel Combustion Mode”. SAE International Journal of Engines,10, pp. 908–916. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q., and Hu, Y., 2016. “A study on the combustion and emission performance of diesel engines under different proportions of O2 & N2& CO2”. Applied Thermal Engineering,108, pp. 508–515. [CrossRef]

- Van Blarigan, A., Kozarac, D., Seiser, R., Cattolica, R., Chen, J.-Y., and Dibble, R., 2014. “Experimental study of methane-fuel OFC in a spark-ignited engine”. Journal of Energy Resources Technology,136, 3. [CrossRef]

- Luján, J.M., Arnau, F.J., Piqueras, P., and Farias, V.H., 2023. “Design of a carbon capture system for oxy-fuel combustion in compression ignition engines with exhaust water recirculation”. Energy Conversion and Management,284, 116979. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.R., Piqueras, P., Sanchís, E.J., and García, F.J., 2025. “Comparative life cycle assessment of oxy-fuel combustion utilization across various fuels in the maritime sector”. Energy Conversion and Management,342, 120034. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., and Yang, W., 2017. Mixed Conducting Ceramic Membranes Fundamentals, Materials and Applications. Springer.

- Wu, F., Argyle, M. D., Dellenback, P. A., and Fan, M., 2018. “Progress in O2 separation for oxy-fuel combustion–A promising way for cost-effective CO2 capture: A review”. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science,67, pp. 188–205. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, R., 2011. “Thermodynamic analysis of a hard coal oxyfuel power plant with high temperature three-end membrane for air separation”. Applied Energy,88(5), pp. 1480–1493. [CrossRef]

- Skorek-Osikowska, A., Łukasz Bartela, and Kotowicz, J., 2015. “A comparative thermodynamic, economic and risk analysis concerning implementation of oxy-combustion power plants integrated with cryogenic and hybrid air separation units”. Energy Conversion and Management,92, pp. 421–430. [CrossRef]

- Portillo, E., Gallego Fernandez, L. M., Vega, F., Alonso-Farinas, B., and Navarrete, B., 2021. “Oxygen transport membrane unit applied to oxy-combustion coal power plants: A thermodynamic assessment”. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering,9(6), 105266. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.R., Arnau, F.J., García-Cuevas, L.M., and Farias, V.H., 2021. “Oxy-fuel combustion feasibility of compression ignition engines using oxygen separation membranes for enabling carbon dioxide capture”. Energy Conversion and Management,247. [CrossRef]

- Arnau, F., Novella, R., García-Cuevas, L. M., and Gutiérrez, F., 2021. “Adapting an internal combustion engine to oxy-fuel combustion with in-situ oxygen production”. ASME 2021 Internal Combustion Engine Division Fall Technical Conference ICEF2021-67707. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.R., Arnau, F.J., García-Cuevas, L.M., and Gutiérrez, F.A., 2023. “Coupling an oxygen generation cycle with an oxy-fuel combustion spark ignition engine for zero NOx emissions and carbon capture: A feasibility study”. Energy Conversion and Management,284, 116973. [CrossRef]

- Arnau, F. J., Benajes, J. V., Catalán, D., Desantes, J. M., García-Cuevas, L. M., Serra, J. M., and Serrano, J. R., 2021. Internal combustion engine and operating method of the same. Motor de combustión interna y método de funcionamiento del mismo. P201930285, 28.03.2019. WO2020/193833A1, 01.10.2020. PCT/ES2020/070199, 21.03.2020. ES2751129B2, 29.03.2021.

- Martin, J. , Arnau, F., Piqueras, P., and Auñón, A., 2018. “Development of an Integrated Virtual Engine Model to Simulate New Standard Testing Cycles”. In WCX World Congress Experience, SAE International 2018-04-03. [CrossRef]

- Komninos, N., and Rogdakis, E., 2018. “Design considerations for an Ericsson engine equipped with high-performance gas-to-gas compact heat exchanger: A numerical study”. Applied Thermal Engineering,133, pp. 749–763. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J. R., Martín, J., Gómez-Soriano, J., and Raggi, R., 2022. “Exploring the oxy-fuel combustion in spark-ignition engines for future clean powerplants”. In Proceedings of the ASME 2022 ICEF 2022. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J. R., Martín, J., Gómez-Soriano, J., and Raggi, R., 2021. “Theoretical evaluation of the spark-ignition premixed oxyfuel combustion concept for future CO2 captive powerplants”. Energy Conversion and Management,244. [CrossRef]

- Arnau, F.J., Bracho, G., García-Cuevas, L.M., and Farias, V.H., 2023. “A strategy to extend load operation map range in oxy-fuel compression ignition engines with oxygen separation membranes”. Applied Thermal Engineering,226, 120268. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.R., Arnau, F.J., Piqueras, P., Contreras-Jimenez, D., Ariztegui, J., and Oliva, F., 2024. “About the Use of Oxyfuel Combustion Engines to Assess the Heat and Power Flexibility Needs of Decarbonised E-Fuel Synthesis Plants While Keeping the Circularity of O2 and CO2 in the Process”. ASME 2024 ICE Forward Conference,Internal Combustion Engine Division Fall Technical Conference, V001T02A005. [CrossRef]

| Type | 4-cylinder 4-stroke spark ignition |

|---|---|

| Valves per cylinder | 4 |

| Bore [] | 72.2 |

| Stroke [] | 81.35 |

| Original compression ratio [-] | 9.6 |

| Displacement [] | 1332 |

| Connecting rod length [] | 128.128 |

| Type | Petrol |

|---|---|

| Formula | |

| Heat value | 42.399 |

| Density | 730.3 |

| Turbine | |

|---|---|

| Wheel diameter | |

| Max. reduced mass flow | /0.5/ |

| Max. reduced speed | /0.5 |

| Compressor | |

| Wheel diameter | 40 |

| Max. corrected mass flow | 0.14 |

| Max. corrected speed (krpm) | 229 |

| Shaft diameter (mm) | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).