Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- PSO-based PID tuning, leveraging swarm intelligence for global parameter optimization;

- GWO-based PID tuning, employing hierarchical search to balance exploration and exploitation; and

- Hybrid PSO–GWO tuning, integrating both paradigms to accelerate convergence and enhance robustness under strong nonlinearities.

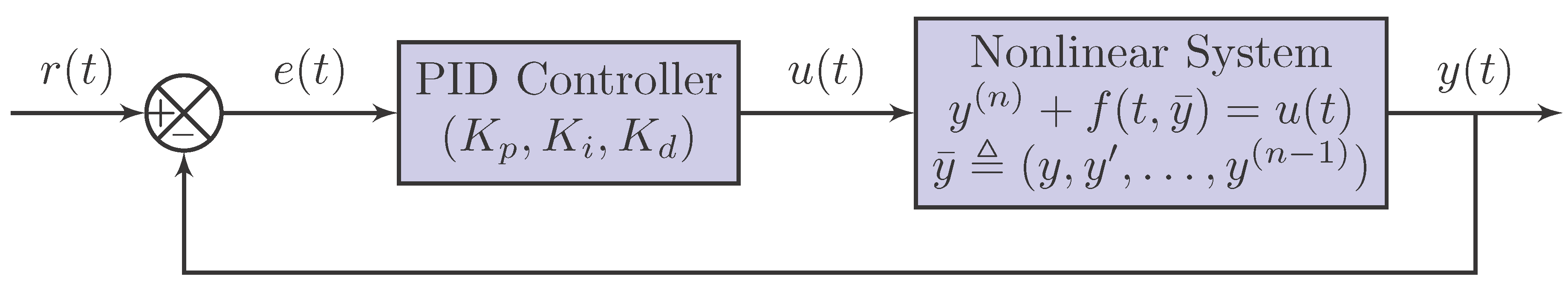

2. Problem Formulation

3. Optimization Framework

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)

Hybrid Strategy: PSO–GWO

- The first sub-swarm updates positions using PSO velocity and position rules, enabling efficient local exploitation.

- The second sub-swarm evolves according to GWO’s hierarchical encircling and hunting behavior, ensuring effective global exploration.

- At each iteration, elite and global best information are exchanged between the sub-swarms to preserve diversity and guide convergence toward the global optimum.

Expected Benefits of the Hybrid PSO–GWO Approach

- Complementary Search Dynamics: The PSO sub-swarm exploits rapid convergence in smooth regions, while the GWO sub-swarm ensures broad exploration in complex, multimodal areas.

- Robustness Against Local Minima: The hybrid structure mitigates premature convergence by leveraging PSO’s memory-guided exploitation and GWO’s stochastic encircling mechanisms.

- Enhanced Population Diversity: Periodic exchange of elite and global best information between sub-swarms maintains diversity and prevents stagnation.

- Improved Convergence Efficiency: Hybridization accelerates convergence by allowing PSO to refine promising regions discovered through GWO’s exploratory search.

- Flexibility in Multi-Objective Optimization: The framework can be extended to handle multiple conflicting objectives, such as minimizing both ITAE and overshoot.

3.1. General Procedure

- Initialization: Define the search space for PID parameters , generate the initial population (particles or wolves) randomly within these bounds, and initialize historical records for tracking cost evaluations.

- Simulation: For each candidate solution, simulate the second-order nonlinear system using the augmented first-order form of the dynamics, integrating the ODEs with a Runge–Kutta solver (RK45) over the simulation horizon.

- Cost Evaluation: Compute the performance index as the sum of ITAE and ISO terms, storing each evaluation for convergence analysis.

-

Position Update:

- In PSO, update particle velocities and positions according to the standard PSO rules, taking into account inertia, cognitive, and social components.

- In GWO, update wolf positions using the encircling, hunting, and attacking strategies defined by the leader hierarchy.

- Global Best Update: Identify the best-performing solution across the population (global best) and update personal or elite records as needed.

- Iteration and Convergence Check: Repeat simulation, evaluation, and update steps for the specified number of generations or until an early stopping criterion is satisfied (e.g., cost improvement below a threshold ).

- Output: The optimal PID parameters , the associated cost , and the total number of cost function evaluations are reported to quantify the performance and computational effort of each optimization strategy.

- Initialization: Define the search space for PID parameters . Initialize the PSO swarm and GWO population randomly within these bounds. Set personal bests for PSO particles and the leader hierarchy for GWO (). Initialize historical records for cost evaluations.

- Simulation: For each candidate solution (particle or wolf), simulate the second-order nonlinear system in augmented first-order form. Integrate the ODEs over the simulation horizon using a Runge–Kutta solver (RK45) to obtain the system response .

- Cost Evaluation: Compute the performance index as the sum of ITAE and ISO terms. Store each evaluation in a history log for convergence analysis and potential CSV export.

-

PSO Update: Update particle velocities and positions using the PSO formula:Clip positions to remain within bounds. Update personal and global bests as necessary.

- GWO Iteration: Execute a single iteration of GWO for the current population. Evaluate costs, update positions based on encircling and hunting mechanisms guided by leaders , and identify the best GWO solution.

- Hybrid Global Best Update: Compare the global best solution from PSO and the best solution from GWO. Update the PSO global best if the GWO solution is superior.

- Iteration and Convergence Check: Repeat PSO and GWO update steps for the specified number of epochs or until the early stopping criterion is satisfied (e.g., improvement below ).

- Output: Report the optimal PID parameters , the associated cost , the total number of cost function evaluations, and the convergence history.

4. Benchmark Nonlinear Systems and Simulation Results

4.1. Benchmark Nonlinear Systems

-

System 1: Pendulum-like nonlinear systemwith parameters , . This system exhibits moderate nonlinearity and resembles the dynamics of a simple pendulum with damping (for ). It is suitable for testing the convergence and robustness of PID tuning algorithms.

-

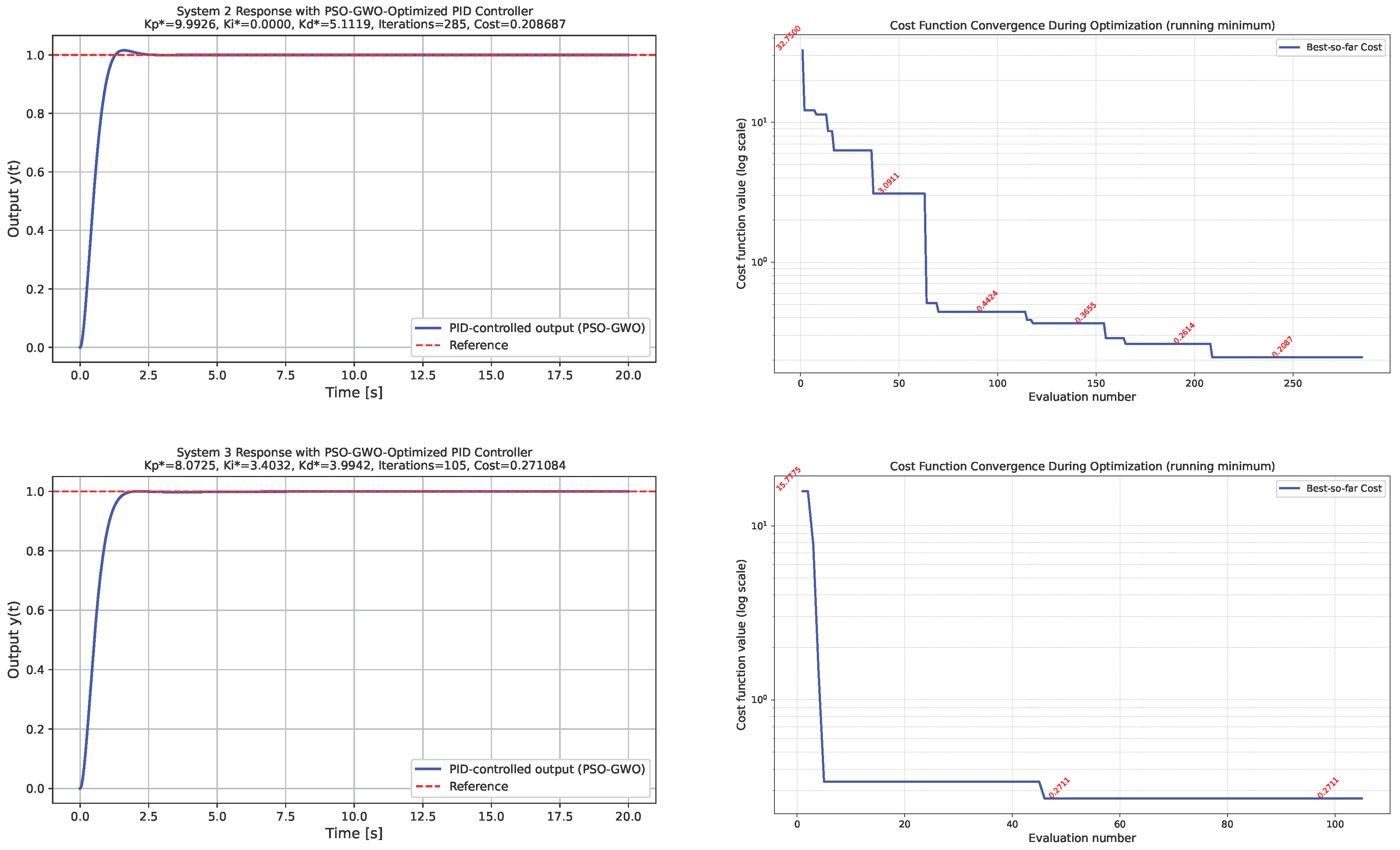

System 2: Duffing oscillatorwith parameters , , . This system is commonly used to test control strategies for stiff and highly nonlinear systems due to the cubic stiffness term, which can produce multiple equilibria and nonlinear oscillatory behavior.

-

System 3: Nonlinear damping systemwith parameters , , . This system introduces a velocity-dependent nonlinear damping term , creating asymmetric transient responses and testing the adaptability of metaheuristic PID tuning.

4.2. PSO Parameters

4.3. GWO Parameters

4.4. Hybrid PSO–GWO Parameters

4.5. Closed-Loop Response under PSO, GWO, and Hybrid PSO–GWO PID Control

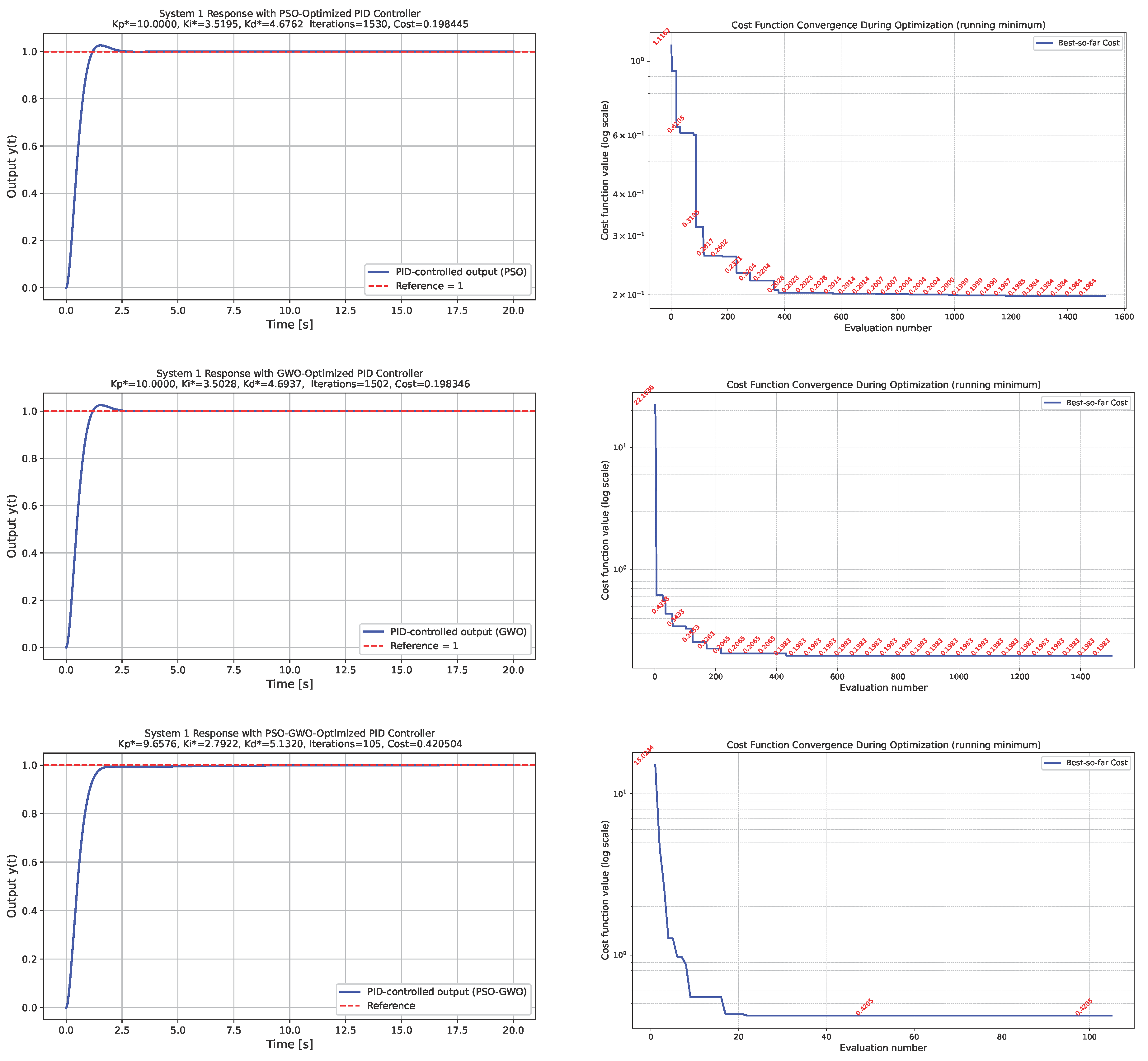

-

System 1: Pendulum-like nonlinear systemFigure 2 presents the simulation results obtained for the pendulum-like nonlinear system. The figure is organized into three rows and two columns. The left column illustrates the closed-loop time responses to a unit-step reference input under the PID gains optimized by the PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO–GWO algorithms, respectively. All three metaheuristic methods successfully stabilize the nonlinear system, while the hybrid PSO–GWO algorithm demonstrates faster convergence and a reduced overshoot compared to the individual approaches. The right column of Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the cost function over successive evaluations, providing insight into the convergence behavior of each optimization strategy. For each case, the achieved minimum cost and the number of evaluations required to reach it are depicted graphically.

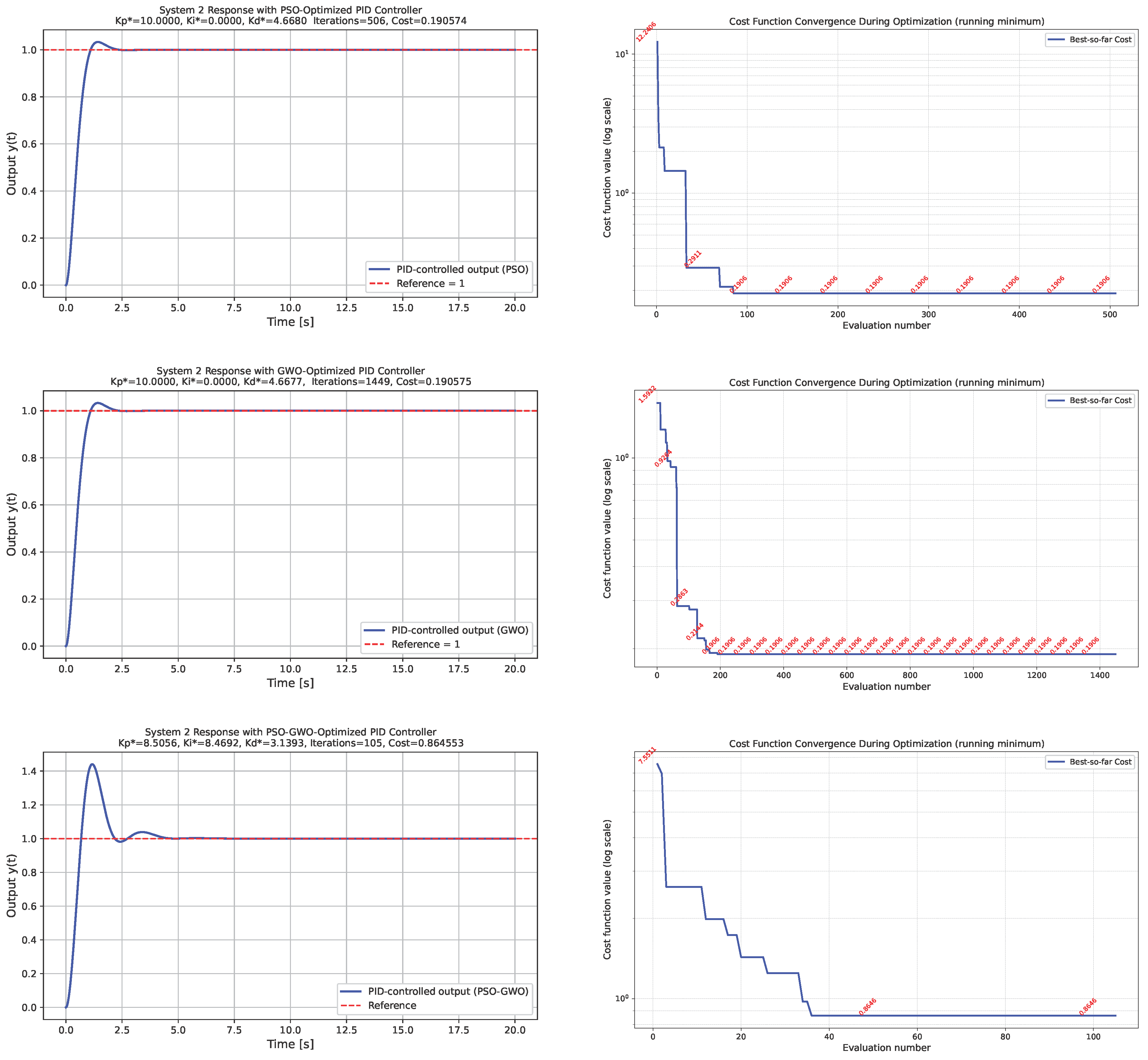

-

System 2: Duffing oscillatorThe response of the Duffing oscillator is presented in Figure 3. Due to the presence of the cubic stiffness term, the system exhibits pronounced nonlinear and potentially oscillatory behavior. The left column of Figure 3 displays the time-domain responses of obtained using PID gains optimized by the PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO–GWO algorithms. All three controllers are able to regulate the system effectively; however, the hybrid PSO–GWO algorithm produces a noticeably higher overshoot compared to PSO and GWO. This behavior can be mitigated by increasing the weight of the ISO term in the performance function. For instance, when , a significant suppression of overshoot is observed, as illustrated in the first row of Figure 5. The right column of Figure 3 provides insights into the convergence of the cost function across iterations.

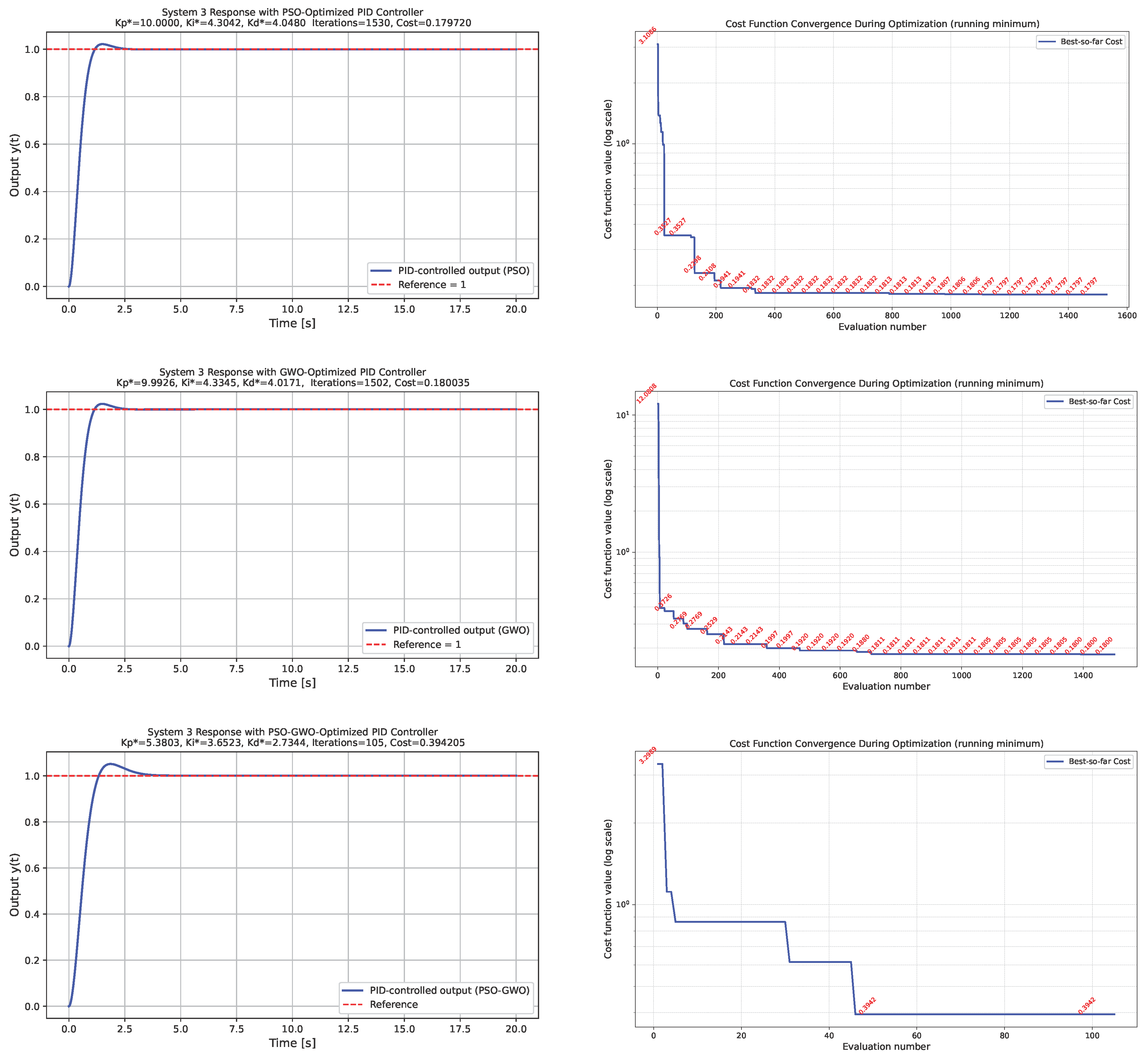

-

System 3: Nonlinear damping systemFigure 4 illustrates the closed-loop behavior of the nonlinear damping system for the PID controllers optimized by PSO, GWO, and the hybrid PSO–GWO algorithm. The left column shows the system responses to a unit-step input. The presence of the velocity-dependent damping term introduces asymmetric transient dynamics and nonlinear dissipation effects. All optimized PID controllers are capable of stabilizing the system; however, the hybrid PSO–GWO approach again exhibits a relatively higher overshoot compared to the standalone PSO and GWO methods. Nevertheless, this increased transient excitation occurs at a substantially lower number of cost function evaluations, indicating a more efficient search process. As in the case of the Duffing oscillator, this overshoot can be mitigated by appropriately increasing the weighting coefficient of the ISO component in the performance index, as can be observed in the second row of Figure 5, thereby emphasizing steady-state accuracy. The right column of Figure 4 depicts the evolution of the cost function during the optimization process, further highlighting the convergence characteristics and trade-offs in exploration and exploitation among the three algorithms.

5. Discussion

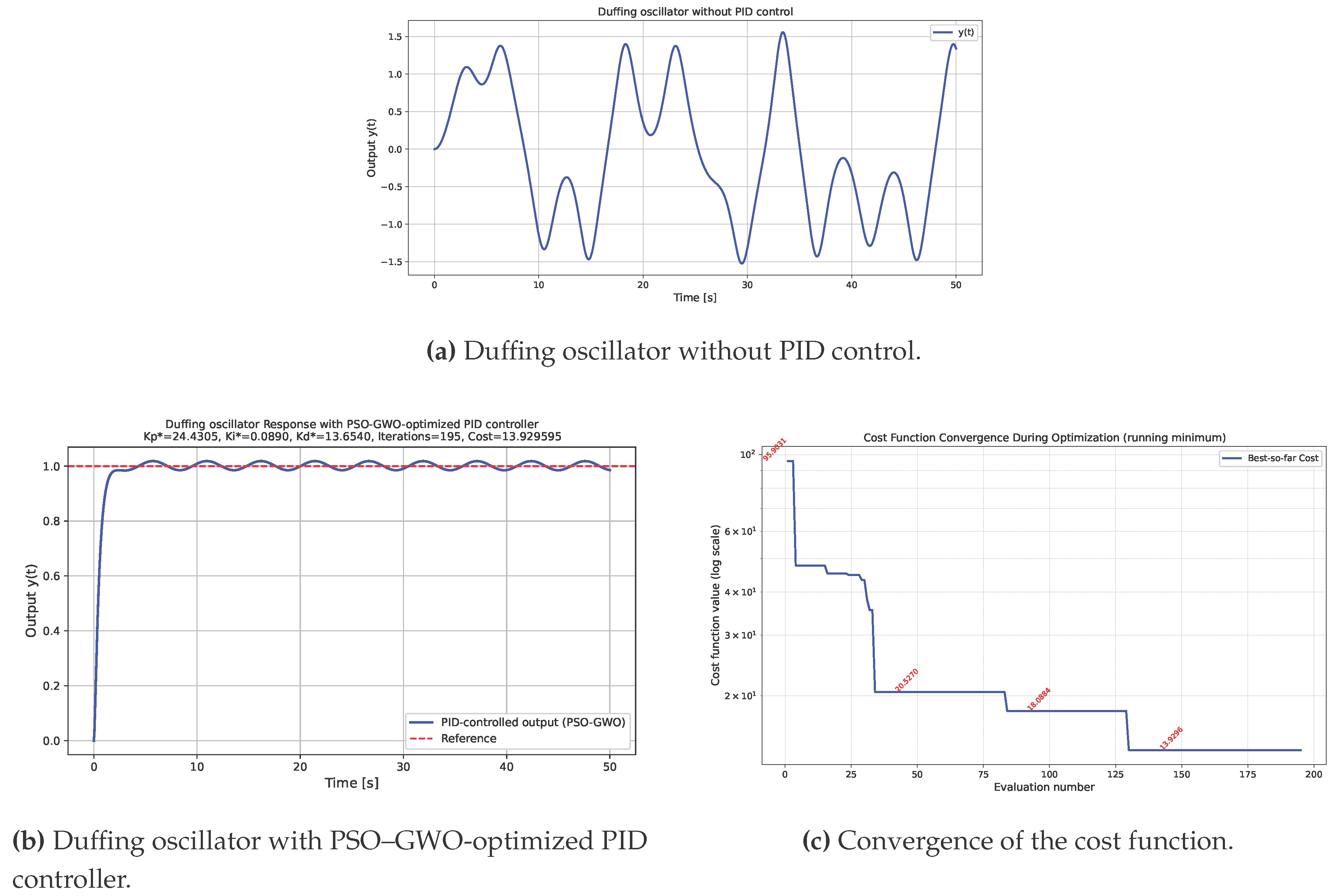

- Computational efficiency: The hybrid PSO–GWO algorithm achieves the target cost values with a substantially smaller number of cost function evaluations-approximately 10% of those required by standalone PSO or GWO. This remarkable reduction can be attributed to the synergy between the exploration capability of GWO and the exploitation behavior of PSO, which enables faster convergence toward promising regions of the search space. The hybrid structure effectively combines global and local search mechanisms, resulting in a rapid decrease in the cost function even in highly nonlinear conditions.

- System performance and overshoot behavior: Although the hybrid PSO–GWO demonstrates excellent convergence speed, its time-domain responses for Systems 2 and 3 exhibit pronounced overshoot and oscillations during the transient phase. This behavior suggests that the algorithm tends to generate aggressive control actions due to a strong emphasis on the integral and derivative gains during the optimization process. The observed overshoot can be mitigated by increasing the weighting factor in the ISO term of the performance function. Numerical experiments show that setting effectively suppresses overshoot without significantly affecting the total number of cost function evaluations, indicating a favorable trade-off between control smoothness and optimization efficiency.

- Comparison of PSO and GWO: Both standalone PSO and GWO algorithms achieve stable control performance with low cost values, though at the expense of considerably higher computational effort. GWO, in particular, exhibits consistent but slower convergence, reflecting its exploratory nature. PSO maintains fast convergence and strong exploitation of promising regions, but requires more evaluations to achieve comparable performance to the hybrid approach.

- Sensitivity to the performance index parameters: The results further confirm that the design of the performance function, particularly the weighting of its integral and overshoot (ISO) components, plays a critical role in shaping controller behavior. For the hybrid PSO–GWO, an insufficiently penalized overshoot term (small ) leads to aggressive transient responses, whereas larger values produce smoother trajectories without degrading the convergence rate. Hence, the parameterization of the performance function directly governs the trade-off between control aggressiveness and robustness.

5.1. Remark on stochastic variability of optimization results.

5.2. Robustness Test on the Chaotic Duffing Oscillator

6. Conclusions and Future Work

- Incorporating adaptive or self-tuning strategies for real-time adjustment of PID gains based on system operating conditions.

- Extending the hybrid optimization framework to multi-objective formulations, balancing competing criteria such as energy consumption, robustness, and tracking precision.

- Applying the proposed approach to higher-order nonlinear and time-delay systems, and validating it through hardware-in-the-loop or real experimental platforms.

- Due to the inherent stochastic nature of metaheuristic optimization, incorporating statistical assessment across multiple independent runs to ensure robust evaluation of convergence characteristics and to quantify the distribution of attainable control performances in strongly nonlinear systems.

Acknowledgement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Funding

Appendix A. PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using PSO

| Algorithm A1 PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using PSO |

|

Appendix B. PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using GWO

| Algorithm A2 PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using GWO |

|

Appendix C. PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using Hybrid PSO–GWO

| Algorithm A3 PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using Hybrid PSO–GWO |

|

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. J. Åström, T. Hägglund, Advanced PID Control, ISA – The Instrumentation, Systems, and Automation Society, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, 2006.

- N. S. Nise, Control Systems Engineering, 6th Edition, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, 2011.

- K. Ogata, Modern Control Engineering, 5th Edition, Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2010.

- D. Çelik, N. Khosravi, M. A. Khan, M. Waseem, H. Ahmed, Advancements in nonlinear PID controllers: A comprehensive review, Computers & Electrical Engineering, In press (October 2025). [CrossRef]

- F. S. Prity, Nature-inspired optimization algorithms for enhanced load balancing in cloud computing: A comprehensive review with taxonomy, comparative analysis, and future trends, Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 97 (2025) 102053. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Eberhart, J. Kennedy, Particle swarm optimization, in: Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, 1995, pp. 1942–1948.

- J. Kennedy, R. C. Eberhart, A discrete binary version of the particle swarm algorithm, in: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 1997, pp. 4104–4108.

- Y. Shi, R. C. Eberhart, A modified particle swarm optimizer, in: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation, 1998, pp. 69–73.

- S. Mirjalili, S. M. Mirjalili, A. Lewis, Grey wolf optimizer, Advances in Engineering Software 69 (2014) 46–61.

- M. A. Shaheen, H. M. Hasanien, A. Alkuhayli, A novel hybrid GWO-PSO optimization technique for optimal reactive power dispatch problem solution, Ain Shams Engineering Journal 12 (1) (2021) 621–630. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Nguyen, Q. A. Nguyen, A multi-objective PSO-GWO approach for smart grid reconfiguration with renewable energy and electric vehicles, Energies 18 (8) (2025). [CrossRef]

- A. B. Alyu, A. O. Salau, B. Khan, J. N. Eneh, Hybrid GWO-PSO based optimal placement and sizing of multiple PV-DG units for power loss reduction and voltage profile improvement, Scientific Reports 13 (2023) 6903. [CrossRef]

- J. Águila León, C. Vargas-Salgado, D. Díaz-Bello, C. Montagud-Montalvá, Optimizing photovoltaic systems: A meta-optimization approach with GWO-Enhanced PSO algorithm for improving mppt controllers, Renewable Energy 230 (2024) 120892. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Bhandari, A. Kumar, M. Ram, Grey wolf optimizer and hybrid PSO-GWO for reliability optimization and redundancy allocation problem, Quality and Reliability Engineering International 39 (3) (2023) 905–921. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Şenel, F. Gökçe, A. S. Yüksel, T. Yiğit, A novel hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm for optimization problems, Engineering with Computers 35 (2019) 1359–1373. [CrossRef]

- A. Bouaddi, R. Rabeh, M. Ferfra, Optimal control of automatic voltage regulator system using hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm-based pid controller, Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics 13 (5) (2023) 8186. [CrossRef]

- S. Charkoutsis, M. Kara-Mohamed, A particle swarm optimization tuned nonlinear PID controller with improved performance and robustness for first order plus time delay systems, Results in Control and Optimization 10 (2023) Article 100289. [CrossRef]

- W. Dillen, G. Lombaert, M. Schevenels, Performance assessment of metaheuristic algorithms for structural optimization taking into account the influence of algorithmic control parameters, Frontiers in Built Environment 7 (2021) 618851. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Juan, P. Keenan, R. Martí, S. McGarraghy, J. Panadero, P. Carro, D. Oliva, A review of the role of heuristics in stochastic optimisation: From metaheuristics to learnheuristics, Annals of Operations Research 320 (2023) 831–861. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

| Population size | N | 30 |

| Inertia weight | 0.7 | |

| Cognitive coefficient | 1.5 | |

| Social coefficient | 1.5 | |

| Max iterations | 50 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

| Population size | N | 30 |

| Max epochs | 50 | |

| Alpha, Beta, Delta weights | – | 1.0 (default) |

| Algorithm / Metric | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | |||

| (10.0, 3.5195, 4.6762) | (10.0, 0.0, 4.6680) | (10.0, 4.3042, 4.0480) | |

| 0.1984 | 0.1906 | 0.1797 | |

| # cost function evaluations | 1530 | 506 | 1530 |

| Stop condition | max iter | early stop | max iter |

| GWO | |||

| (10.0, 3.5028, 4.6937) | (10.0, 0.0, 4.6677) | (9.9926, 4.3345, 4.0171) | |

| 0.1983 | 0.1906 | 0.1800 | |

| # cost function evaluations | 1502 | 1449 | 1502 |

| Stop condition | early stop | early stop | early stop |

| Hybrid PSO–GWO | |||

| (9.6576, 2.7922, 5.1320) | (8.5056, 8.4692, 3.1393) | (5.3803, 3.6523, 2.7344) | |

| 0.4205 | 0.8646 | 0.3942 | |

| # cost function evaluations | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Stop condition | early stop | early stop | early stop |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).