1. Introduction

Controlled Source Audio-Magnetotellurics (CSAMT) is a frequency-domain artificial source electromagnetic detection technology derived from Audio-Magnetotellurics (AMT) and Magnetotellurics (MT) [

1]. In the 1950s, based on an article published by Cagniard, a method for electromagnetic sounding was developed, which calculates apparent resistivity by observing the orthogonal components of natural electric and magnetic fields [

2]. Within the audio range (10

-1 to 10

3 Hz), the natural electromagnetic field is relatively weak and there can be considerable human-made interference. In the 1970s, Professor D.W. Strangway and others proposed observing the audio electromagnetic field generated by an artificial source using the AMT measurement method. Since the artificial electromagnetic field allows control over frequency, intensity, and direction, and the observation method is similar to AMT, it is therefore called Controlled Source Audio-Magnetotelluric sounding [

3].

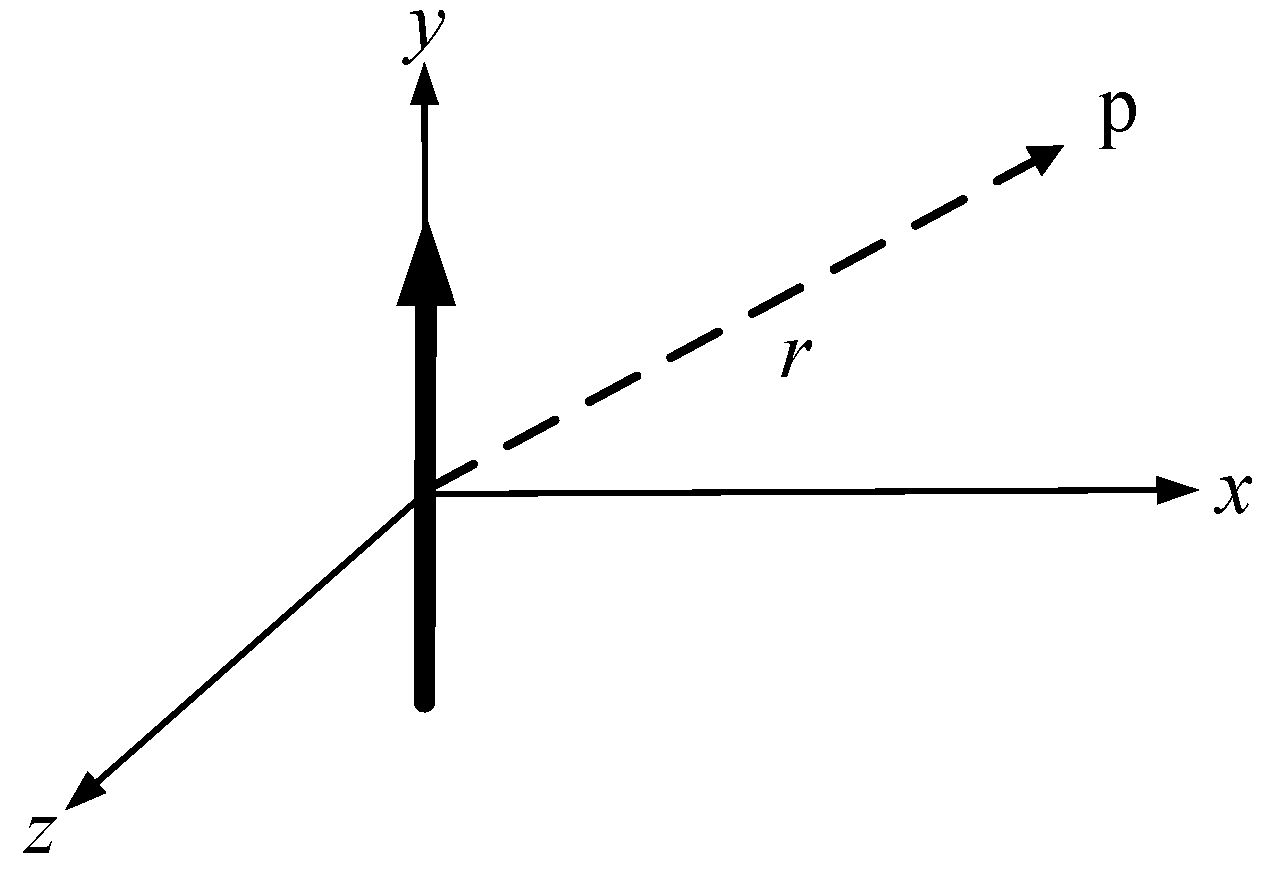

Due to the strong absorption of electromagnetic waves by the earth's medium, the detection depth increases as the emission frequency decreases [

4], which necessitates increasing the transmission and reception distance (r > 4δ) to satisfy the quasi-plane wave assumption in the far field. Conventional CSAMT employs long-wire sources (1–3 km), equivalent to horizontal electric dipoles, which can be approximated as omnidirectional point sources in the far field (r > 10 km) [

5]. Their omnidirectional radiation characteristics lead to significant energy dispersion, with only a small portion of the radiated energy being effectively captured. In addition, long-distance transmission losses and increasing anthropogenic noise interference result in a significant reduction in the signal-to-noise ratio of the received signal, severely limiting detection resolution and data quality [

6].

The traditional controlled-source audio-frequency magnetotelluric (CSAMT) method typically relies on increasing transmitter power or reducing the transmission-reception distance to enhance signal amplitude in the far-field region [

7]. However, the former is limited by power electronics technology, resulting in bulky equipment and difficulties in field deployment; reducing the transmission-reception distance sacrifices detection depth and introduces significant source field effects [

8]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a new type of source technology that can efficiently utilize radiated energy while maintaining the existing transmitter power. This study focuses on proposing a tensor CSAMT method based on an L-shaped array artificial source and its engineering implementation. The design replaces the two traditionally separated single-dipole sources with two sets of orthogonal coaxial linear dipole arrays forming an L-shaped structure. Field test data fully demonstrate that this array antenna-based artificial source can effectively reduce multipath interference, achieve adaptive directional radiation to specific areas, and significantly improve the signal-to-noise ratio and resolution of exploration data, providing a powerful technical means for deep resource exploration in complex environments. It lays a theoretical foundation for adaptive exploration.

CSAMT is a frequency-domain electromagnetic method that belongs to the artificial source methods. When observations are made in the far-field zone, its data can correctly reflect changes in the geoelectric structure [

9]. However, in other areas, due to the influence of artificial sources, non-plane wave effects related to the transmission frequency are generated—in other words, influenced by the transition zone and near zone—resulting in significant distortions in the apparent resistivity curves of the Cagniard method, manifested as a 45° rise at low frequencies on the log-log scale [

10]. This is known as the near-field effect. In practical exploration, MT two-dimensional or three-dimensional inversion software can only invert far-field data. However, when measuring in the far-field zone, the signal-to-noise ratio is often not high and is easily disturbed, while shortening the transmitter-receiver distance is affected by near-field effects. This significantly limits the penetration depth of the CSAMT method [

11]. Currently, most scholars focus on solving near-field effects and increasing transmitter power, while there is relatively little research on improving the energy utilization of artificial sources. Based on long-offset transient electromagnetic methods, Xue Guoqiang et al. proposed the short-offset transient electromagnetic method. By exciting electromagnetic field signals using grounded line sources and observing the response in the near-source zone along the equator, with offset distances typically 0.5–1.5 times the exploration depth, this method can achieve deep exploration with relatively short offsets [

12].

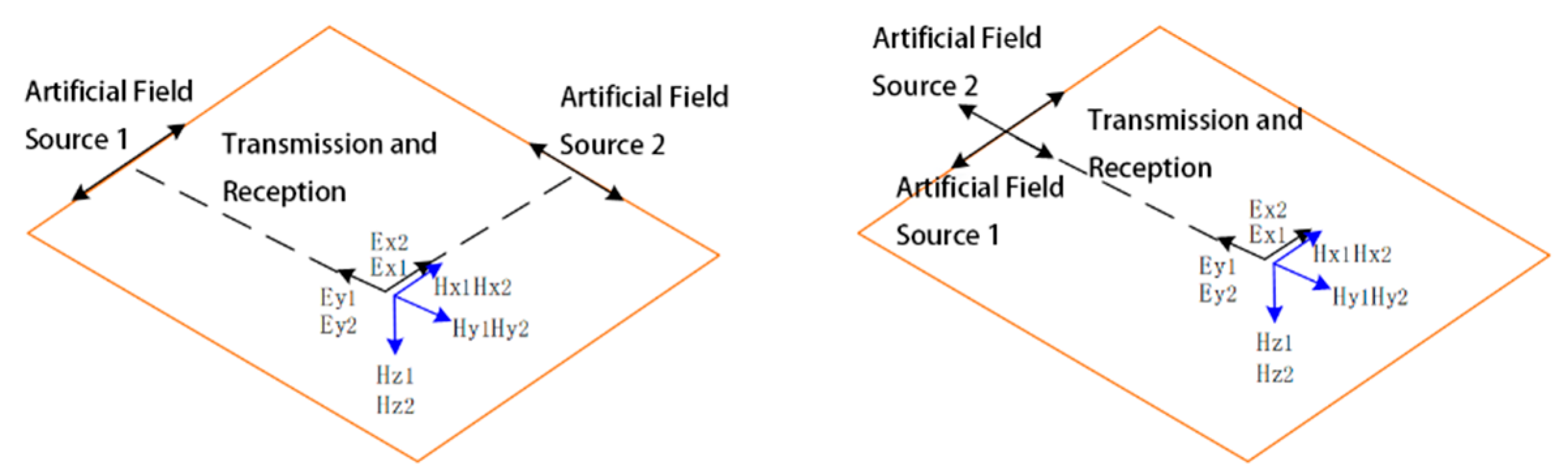

The CSAMT method can use either magnetic field sources or electric field sources as artificial sources. Due to differences in implementation, to achieve the exploration effect of an electric field source, a magnetic field source requires more than 10 times the supply current [

13]; therefore, in practice, electric field sources are mainly used. Tensor CSAMT employs two grounded horizontal electric dipole antennas in mutually perpendicular directions, allowing the establishment of a three-dimensional current field underground. Since the grounded horizontal electric dipole antennas in these two directions are independent dipoles with individually varying electromagnetic field components, they can measure a total of 10 components [

14]. Tensor CSAMT typically uses two mutually perpendicular sources to establish a three-dimensional current field underground and measure the 10 components of the electromagnetic field. The electromagnetic field components generated by the horizontal dipole are

, while those in the perpendicular direction are

. All 10 components need to be measured to determine the impedance tensor. Common tensor CSAMT construction instruments include two types: L-shaped sources and cross-shaped sources.

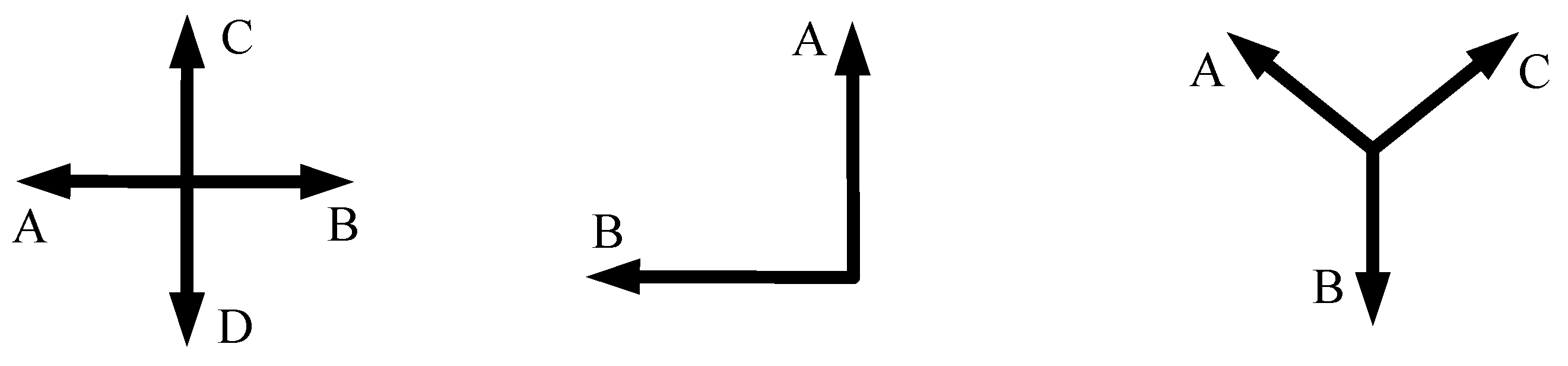

The leftmost type in

Figure 1 is the tensor CSAMT cross-shaped field source transmitter, with its core consisting of two sets of horizontal electric dipoles arranged perpendicularly [

15]. In operation, the transmitter alternately supplies power to the two electrode pairs (A-B and C-D), thereby generating underground current fields in the x and y directions, respectively. This time-sharing excitation method allows the receiver to independently observe the electromagnetic field responses in the two orthogonal directions. The middle type in

Figure 1 is the tensor L-shaped field source transmitter, also composed of two mutually perpendicular horizontal electric dipoles [

16]. At a certain point in the far-field region, the electromagnetic field intensities produced by horizontal electric dipole 1 are

、

、

、

, and at the same point, those produced by horizontal electric dipole 2 are

、

、

、

. At that point, the electromagnetic field intensity of the L-shaped field source follows the principle of vector superposition, meaning that the fields from multiple dipole sources can be combined according to vector addition. Therefore, the electromagnetic field at a given point generated by these dipole sources is equal to the vector sum of the fields produced by each dipole at that point.

The rightmost part of

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of a rotating dipole device, which is different from the two transmission devices above. This device consists of three pairs of dipole transmitters, each made up of three grounded electrodes, A, B, and C. In other words, the three electrodes are respectively connected to the outputs of the tensor transmitter. Under the control of the pulse width modulation controller, the device simultaneously sends the same specified amplitude, frequency, and adjustable polarity currents

,

and

underground. These three currents combine underground to form the current vector I at the specified frequency. Changing the polarity and amplitude of any of these three currents, according to the vector synthesis principle, will also change the amplitude and polarity of I. Therefore, by selecting the currents

,

and

, electromagnetic field signals in any polarization direction can be obtained.

The antenna system is the core device for transmitting and receiving radio waves, responsible for converting guided waves into electromagnetic waves and vice versa. Basic antennas can handle conventional tasks, but modern radio systems demand higher performance, such as low sidelobe anti-interference [

17], specific beam coverage, and spatial scanning [

18]. To address these needs, array antenna technology arranges multiple identical antenna elements in a regular linear or planar configuration, applies excitation to them, and leverages electromagnetic wave interference to achieve enhanced directivity or beam control [

19]. Developed since the mid-20th century, this technology has been applied in radar, satellite communications, resource exploration, and environmental monitoring [

20], and has spurred the development of pattern synthesis technology to optimize performance.

The radiation pattern of an array antenna can be flexibly controlled by adjusting the number of elements, layout, excitation amplitude, and phase [

21]. For different application scenarios, such as low sidelobe anti-interference, null suppression, or flat-top beam coverage, the pattern shape needs to be customized [

22]. The main methods for pattern synthesis include deterministic synthesis (achieving precise correlation through mathematical functions [

23]) and stochastic synthesis, which relies on random or global optimization algorithms [

24].

1) Deterministic Synthesis Methods: These include two methods for uniform array needle beams: the Dolph-Chebyshev synthesis method and the Taylor synthesis method [

25], as well as two methods for shaped pattern synthesis: the Woodward-Lawson and Elliott-Stern synthesis methods [

26].In array antenna pattern synthesis, Dolph initially used Chebyshev polynomials to optimize the performance of side-lobe arrays [

27], controlling the excitation amplitude through polynomial coefficients to minimize the main lobe width at a fixed side-lobe level. However, when the number of array elements increases, this method reveals some drawbacks, such as all-equal side-lobes wasting radiated power and uneven edge current distribution. Taylor addressed these issues by utilizing the side-lobe attenuation characteristics of the sampling function (Sa function), combining the Sa function with the ideal spatial factor of a line source, and proposing the Taylor synthesis method [

28], which decreases the side-lobe level starting from the nth side-lobe while keeping equal side-lobes in the main beam region. This method has become mainstream for low side-lobe synthesis, and deterministic synthesis methods are characterized by low computational load and high speed.

2) Uncertainty Synthesis Algorithms: Global optimization algorithms or stochastic optimization algorithms are a class of algorithms for solving non-convex optimization problems to search for the global optimum [

29]. Common algorithms include genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, particle swarm optimization, cross-entropy algorithms, differential evolution algorithms, and so on [

30]. These methods are mainly applied to non-convex optimization problems in array antenna pattern synthesis, such as array sparsity, and can achieve good results [

31]. However, these global optimization algorithms are computationally intensive, and the computation increases rapidly as the number of unknowns grows [

32].With social progress, human-made interference in the environment has become increasingly severe, and electronic noise poses a significant threat to CSAMT data reception [

33]. Artificial source antennas act as spatial filters in exploration [

34], serving as the first line of defense against interference in CSAMT [

35]. Antenna anti-interference technologies mainly include low-sidelobe/ultra-low-sidelobe designs, sidelobe masking, adaptive sidelobe cancellation, adaptive array systems, beam control, antenna coverage, and scanning control, among others [

36]. Conventional single-dipole antennas and non-adaptive array antennas have fixed beam directions, making it impossible to automatically track the reception point while suppressing interference, which makes it difficult to meet the exploration requirements in complex electromagnetic environments [

37].

The fundamental difference between adaptive beamforming and non-adaptive beamforming (i.e., pattern synthesis) lies in the method for determining weights: the former calculates the element weights dynamically based on real-time received signals, while the latter sets fixed weights according to a predesigned target pattern. The pattern of adaptive beamforming can change adaptively with interference signals and noise environments, thereby significantly improving resolution and interference suppression capabilities. As an emerging approach, adaptive array antenna technology achieves real-time beam control through algorithms, with the core objective of autonomously aligning the direction of receiving units while maintaining low sidelobe characteristics of the main beam, maximizing the amplitude of received electric field signals, and effectively suppressing or reducing interference intensity.

Based on the fixedness of the weight vector, beamformers can be divided into adaptive and conventional types [

40]. The conventional type uses a fixed weight vector, which is simple to implement but limited by the uncertainty of the received signal, resulting in restricted estimation performance [

41]. Adaptive beamforming technology dynamically optimizes the weight vector using received data and specific design criteria such as minimum mean square error, minimum variance, constant modulus, or maximum signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) criteria, enhancing interference suppression and improving resolution [

42]. This paper focuses on the adaptive beamforming method based on the maximum SINR criterion, conducting an in-depth study of adaptive beamforming techniques for L-shaped array field sources, with particular emphasis on exploring the algorithm's potential in suppressing side interference and dynamically optimizing beam direction. Its ultimate value lies in providing a novel intelligent field source solution for high-precision tensor CSAMT exploration.

5. Conclusion

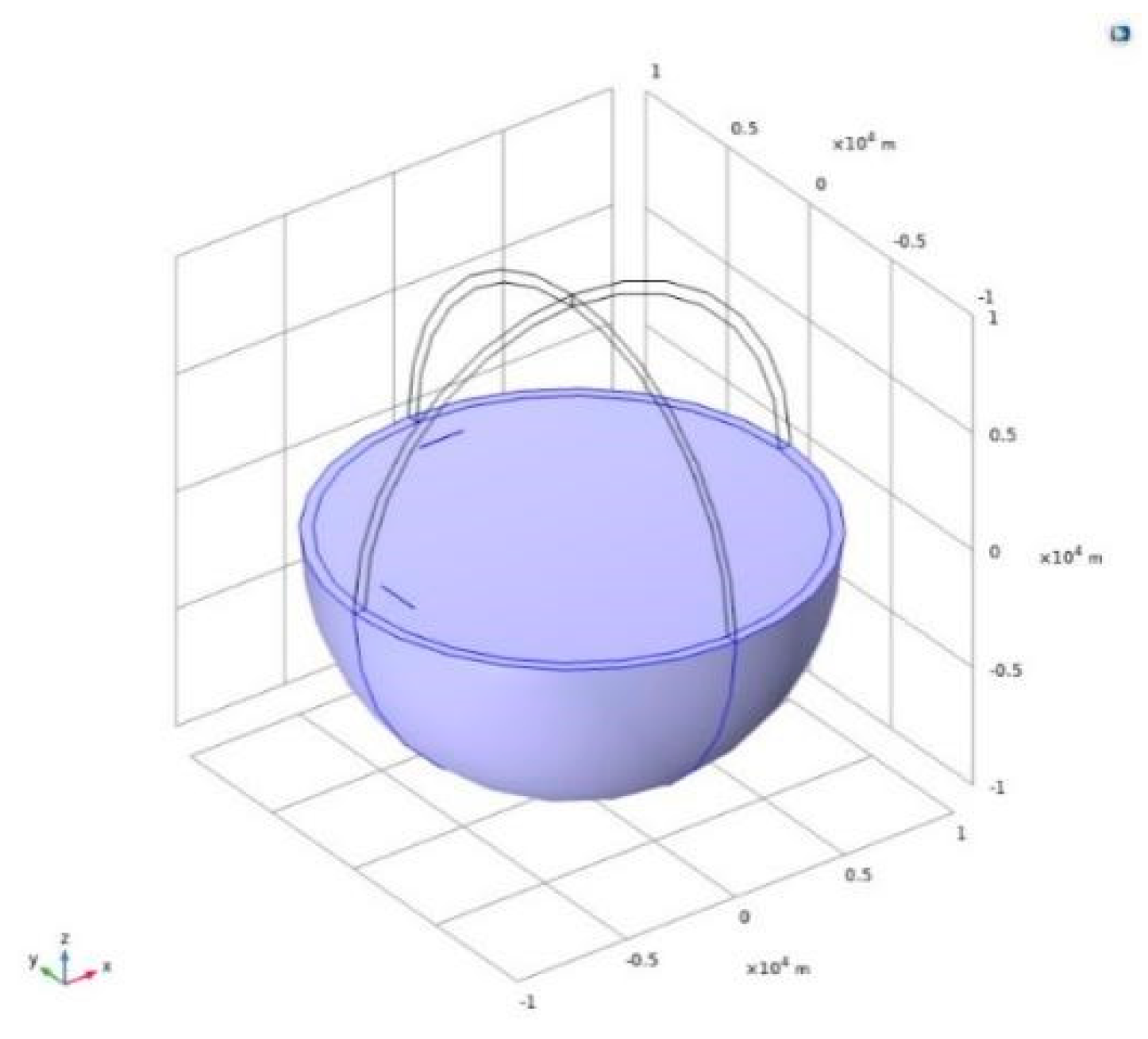

To address the problem of low energy utilization in the far-field region of CSAMT, this study proposes a tensor CSAMT pattern synthesis and adaptive beamforming method based on an L-shaped array of artificial source fields, aiming to improve exploration signal-to-noise ratio and resolution. Through system simulations, numerical modeling, and field tests, the following key conclusions were drawn.:

A tensor CSAMT method based on an L-shaped array artificial field source is proposed, synthesizing a controllable radiation field through two sets of orthogonal coaxial dipole linear arrays. Compared with traditional separated field sources, the L-shaped array has the capability of pattern synthesis and beam scanning, effectively addressing the issues of energy dispersion and limited exploration range in conventional tensor measurements. Based on the maximum amplitude criterion, an adaptive beamforming system is established. By feedback of the electric field data at the receiving end, the phase and amplitude parameters of the transmitting array are adjusted in real time to achieve dynamic beam direction optimization, significantly improving the signal-to-noise ratio in the target area.

A CSAMT adaptive transceiver system based on Beidou RDSS short messages was developed, achieving time synchronization and remote parameter control between the transmitter and receiver. Field tests showed that the system could stably perform beam scanning and energy focusing, verifying the engineering feasibility of the adaptive approach. After combining an L-shaped array with Taylor weighting, the sidelobe level was reduced by about 7 dB, and the main lobe energy was significantly concentrated. With the same transmission power, the effective exploration range was expanded, and the signal-to-noise ratio of the received signal improved, providing technical support for detecting complex geological targets. This study realized the transition of the CSAMT artificial source from 'omnidirectional radiation' to 'directionally controllable' through array antenna technology, offering a new high signal-to-noise, high-efficiency electromagnetic detection paradigm for deep resource exploration.

Although the array antenna artificial field source developed in this project, which can perform pattern synthesis and adaptive beamforming, has achieved good results in simulations and numerical modeling, there are still many issues that need to be addressed, mainly as follows:

(1) Optimization of field source deployment efficiency. The current array antenna-type field source requires far more grounding electrodes than traditional single dipole sources, resulting in a significant increase in field deployment workload. In the future, more efficient deployment solutions and automation technologies need to be studied to balance the contradiction between high-performance exploration and field operation efficiency.;

(2) More comprehensive adaptive acquisition parameters. Currently, adaptive algorithms mainly rely on the criterion of maximizing the electric field amplitude and have not fully utilized magnetic field component information. In the future, the joint optimization acquisition strategy of electric and magnetic field data will be explored to further improve data quality and anti-interference capability through multi-parameter integration.;

(3) Higher device integration. The existing system adopts a separate architecture with GPS timing and Beidou RDSS short message communication. The next step will be to promote the integrated combination of timing and communication functions, utilizing the high-precision timing capabilities of the Beidou system itself, simplifying device configuration, and improving the system's reliability and engineering applicability.

Figure 1.

Artificial field source type of tensor CSAMT.

Figure 1.

Artificial field source type of tensor CSAMT.

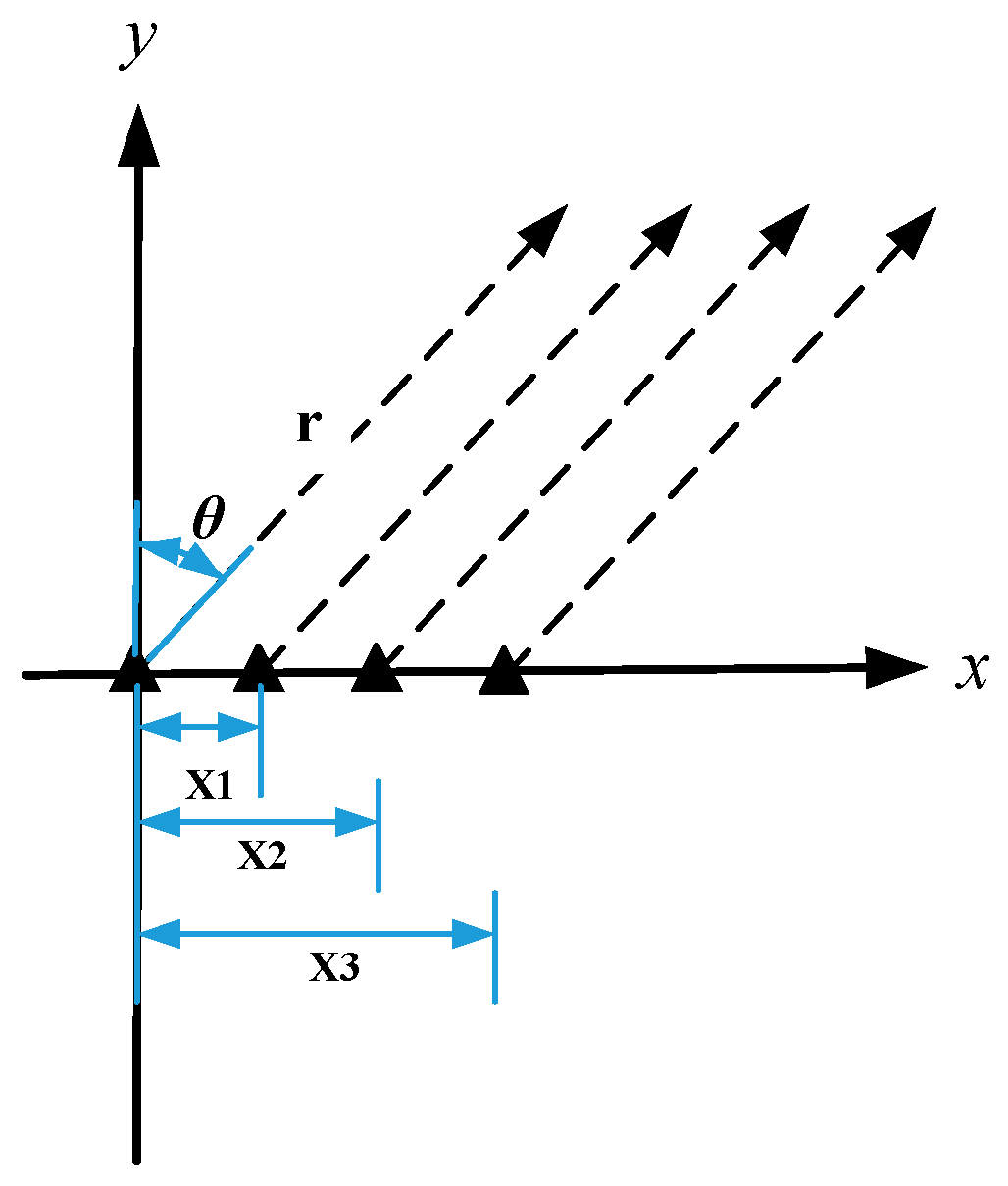

Figure 3.

Linear radiation source.

Figure 3.

Linear radiation source.

Figure 4.

Uniform linear array.

Figure 4.

Uniform linear array.

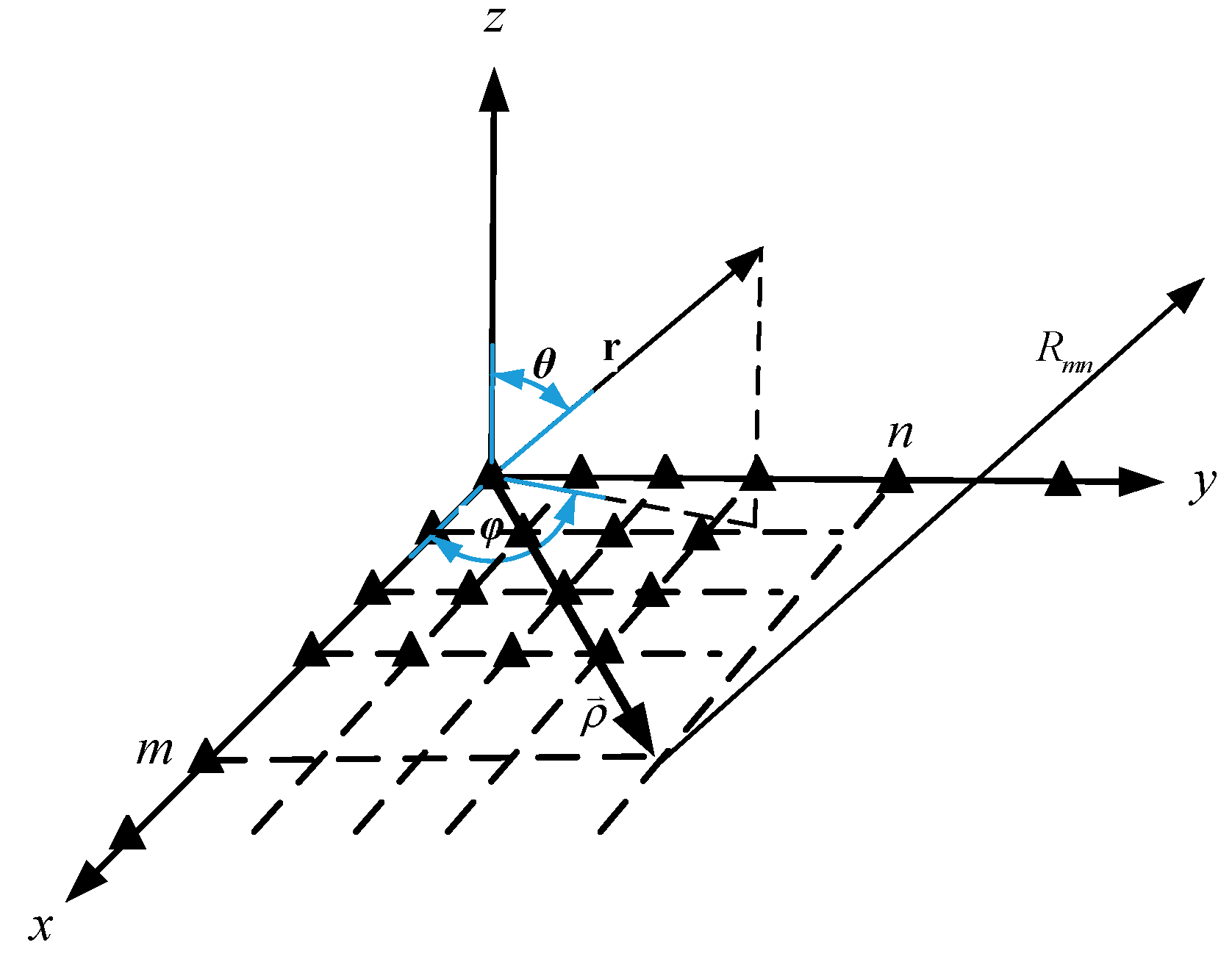

Figure 5.

Uniform planar array.

Figure 5.

Uniform planar array.

Figure 6.

The traditional separation tensor CSAMT model based on single electric dipole antenna artificial field source.

Figure 6.

The traditional separation tensor CSAMT model based on single electric dipole antenna artificial field source.

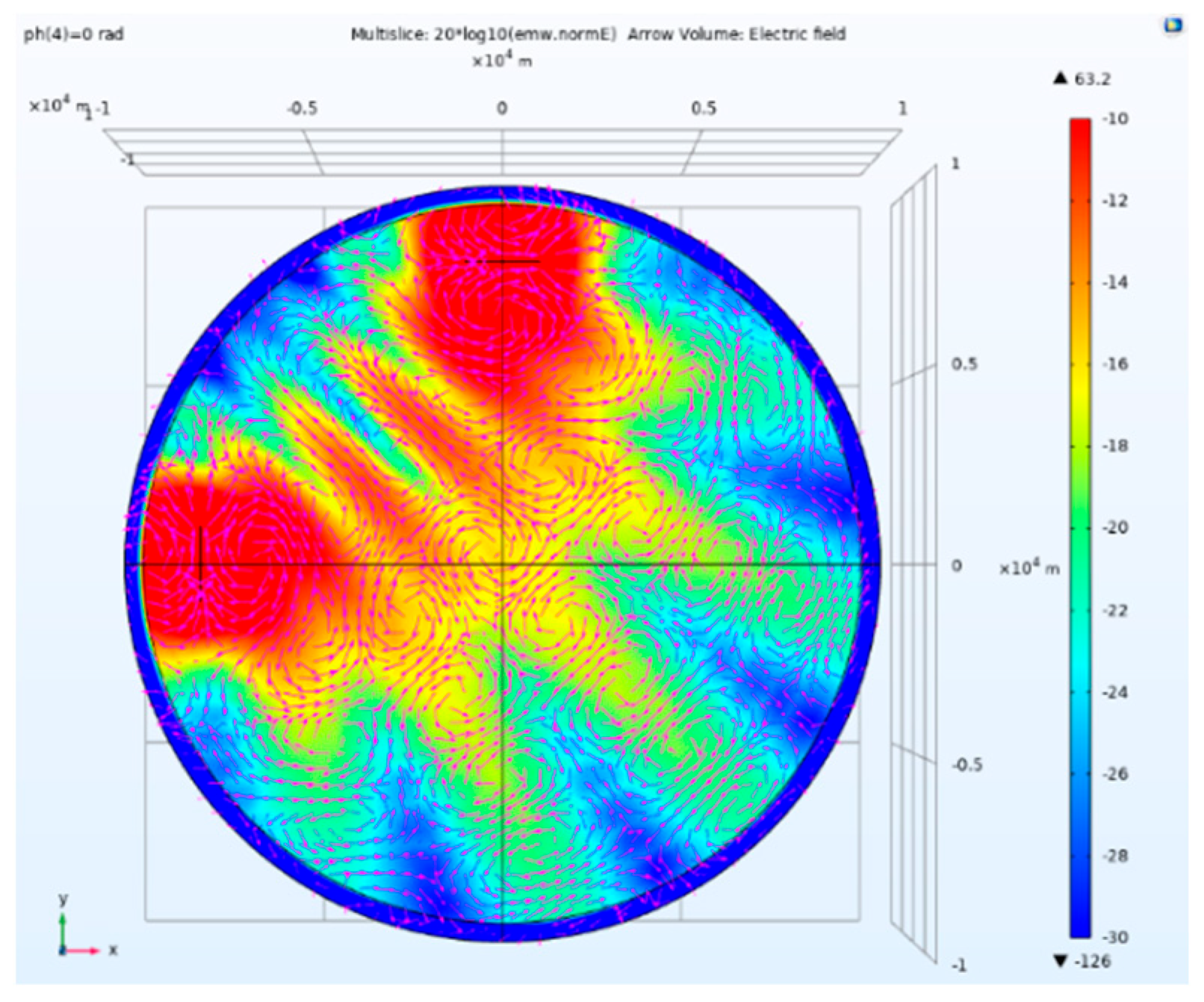

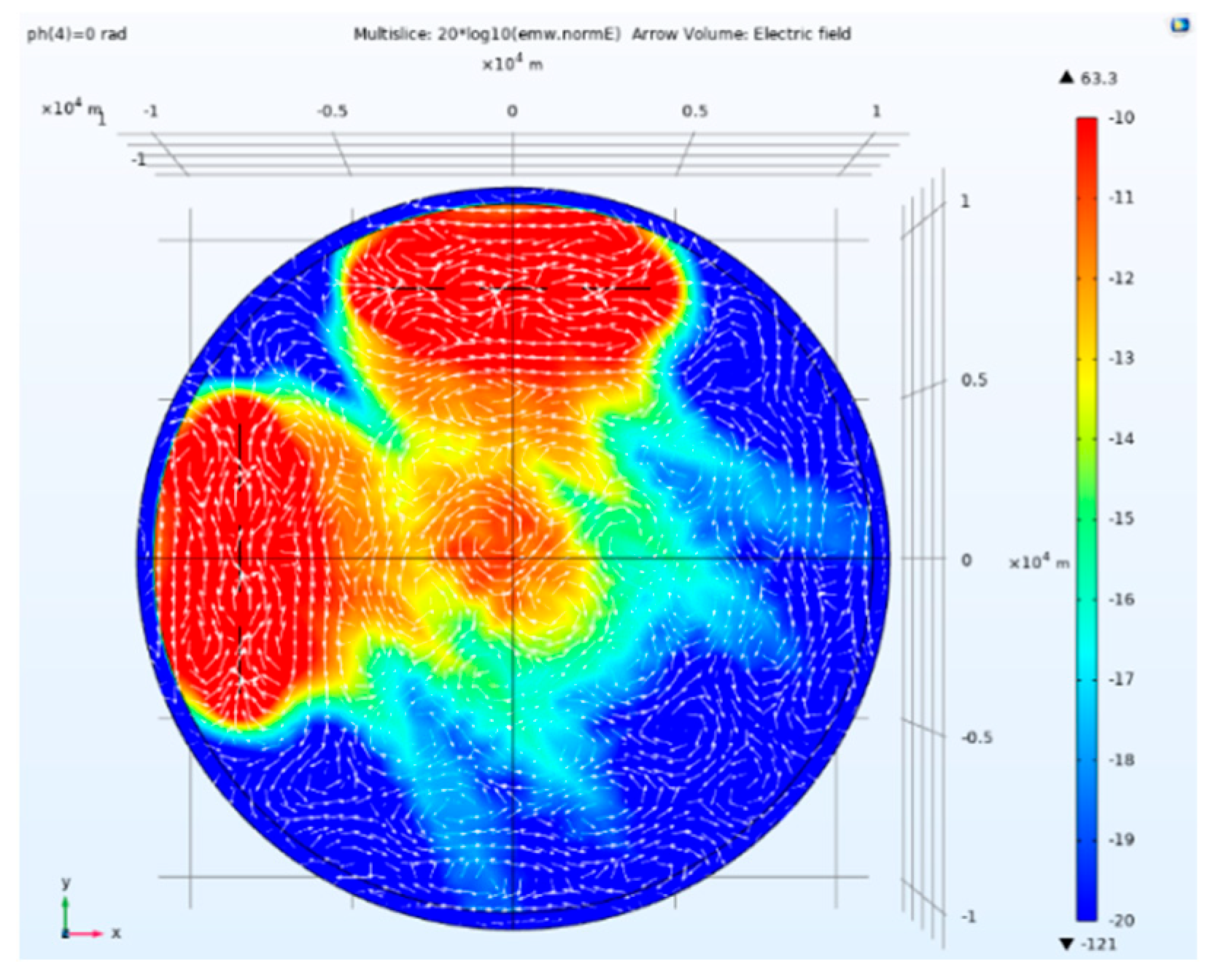

Figure 7.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of traditional separation tensor CSAMT.

Figure 7.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of traditional separation tensor CSAMT.

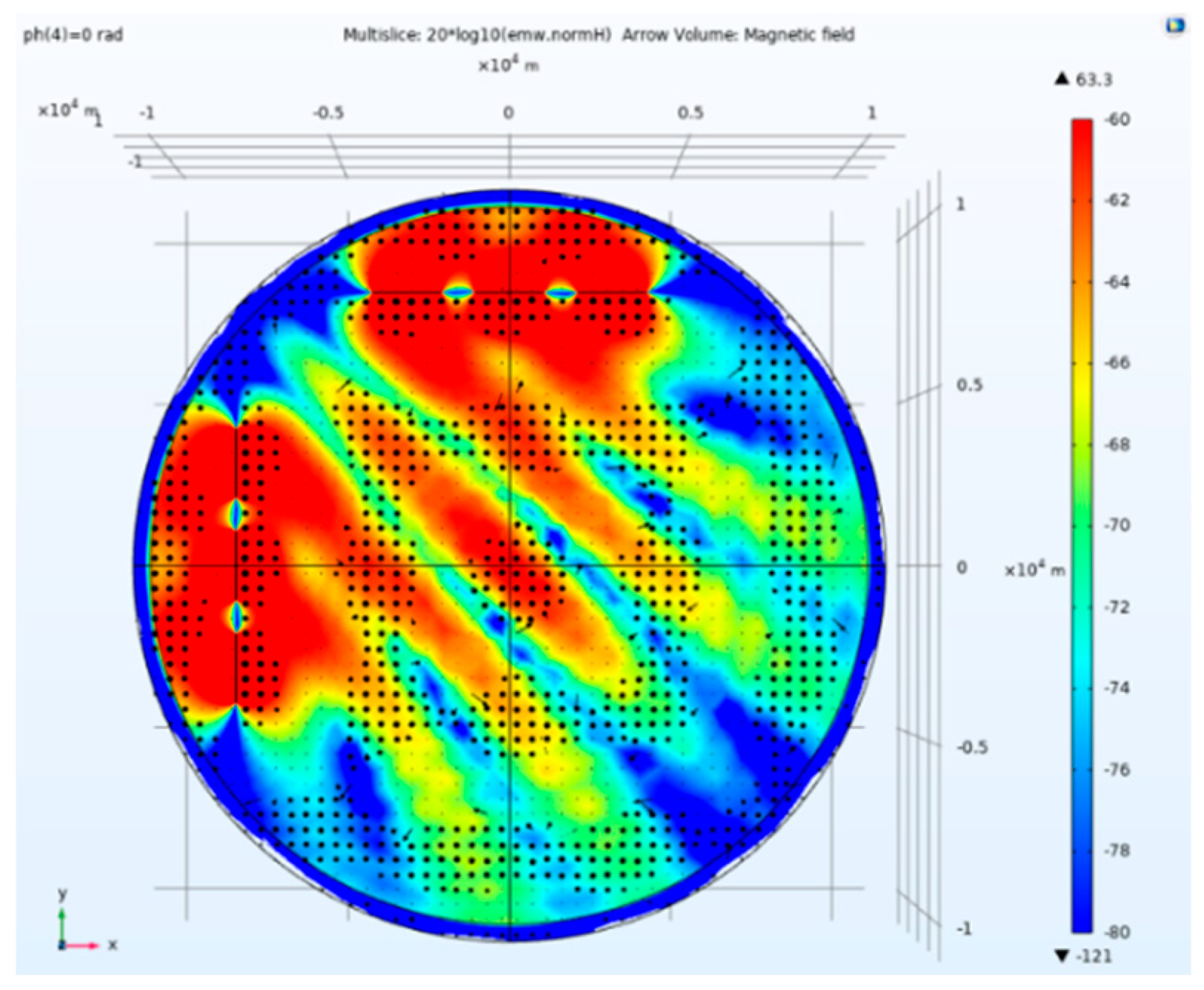

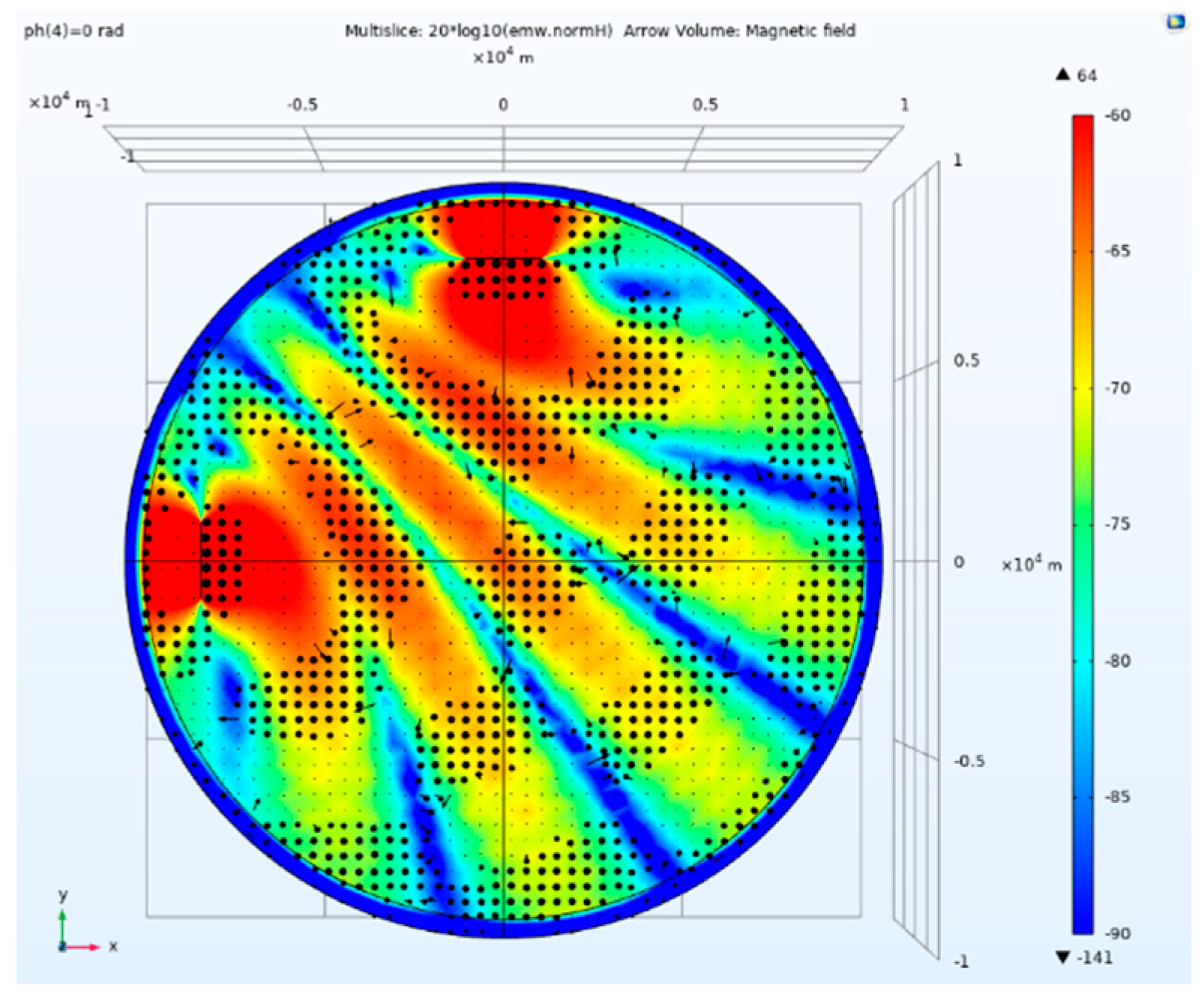

Figure 8.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of traditional separation tensor CSAMT.

Figure 8.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of traditional separation tensor CSAMT.

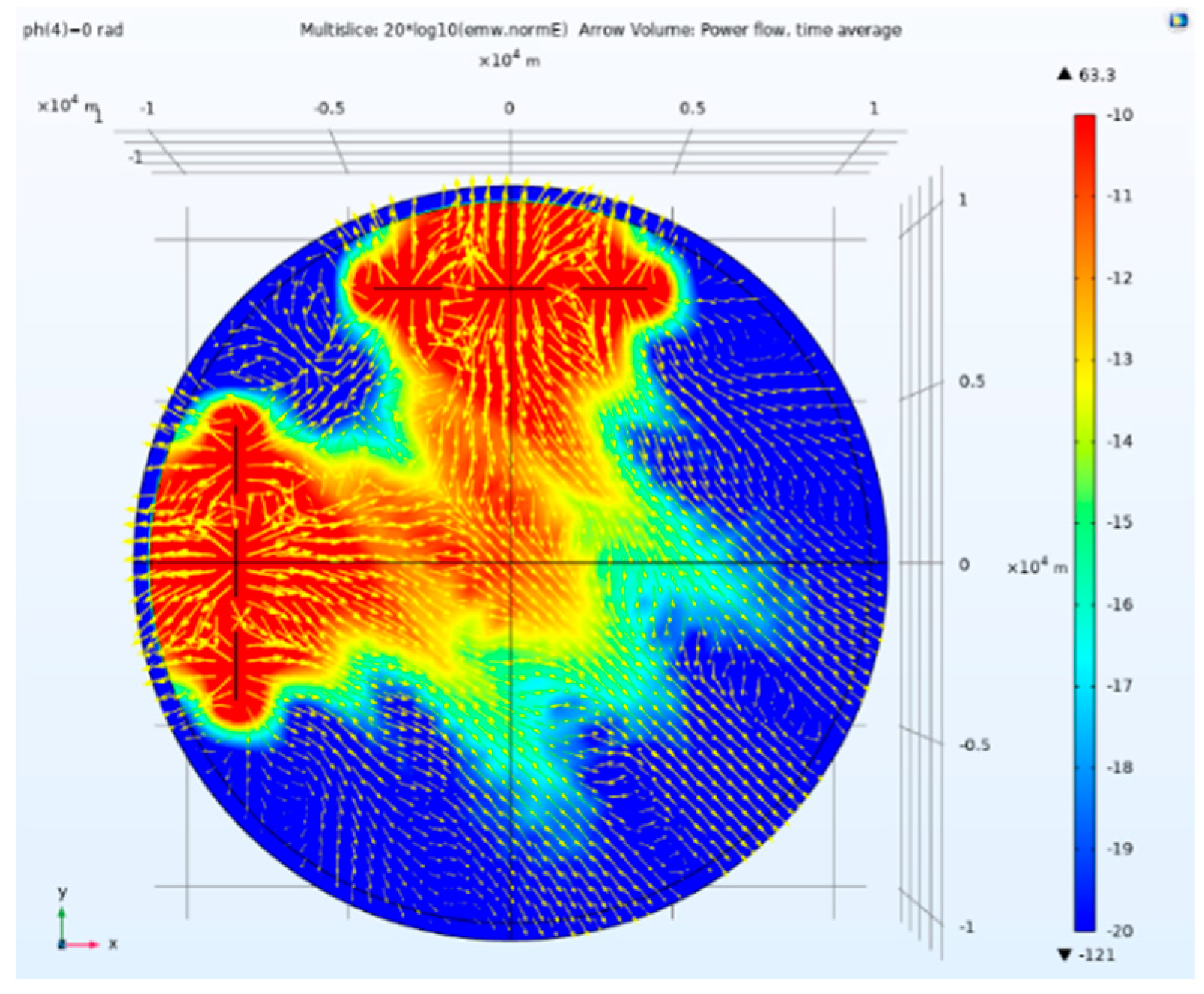

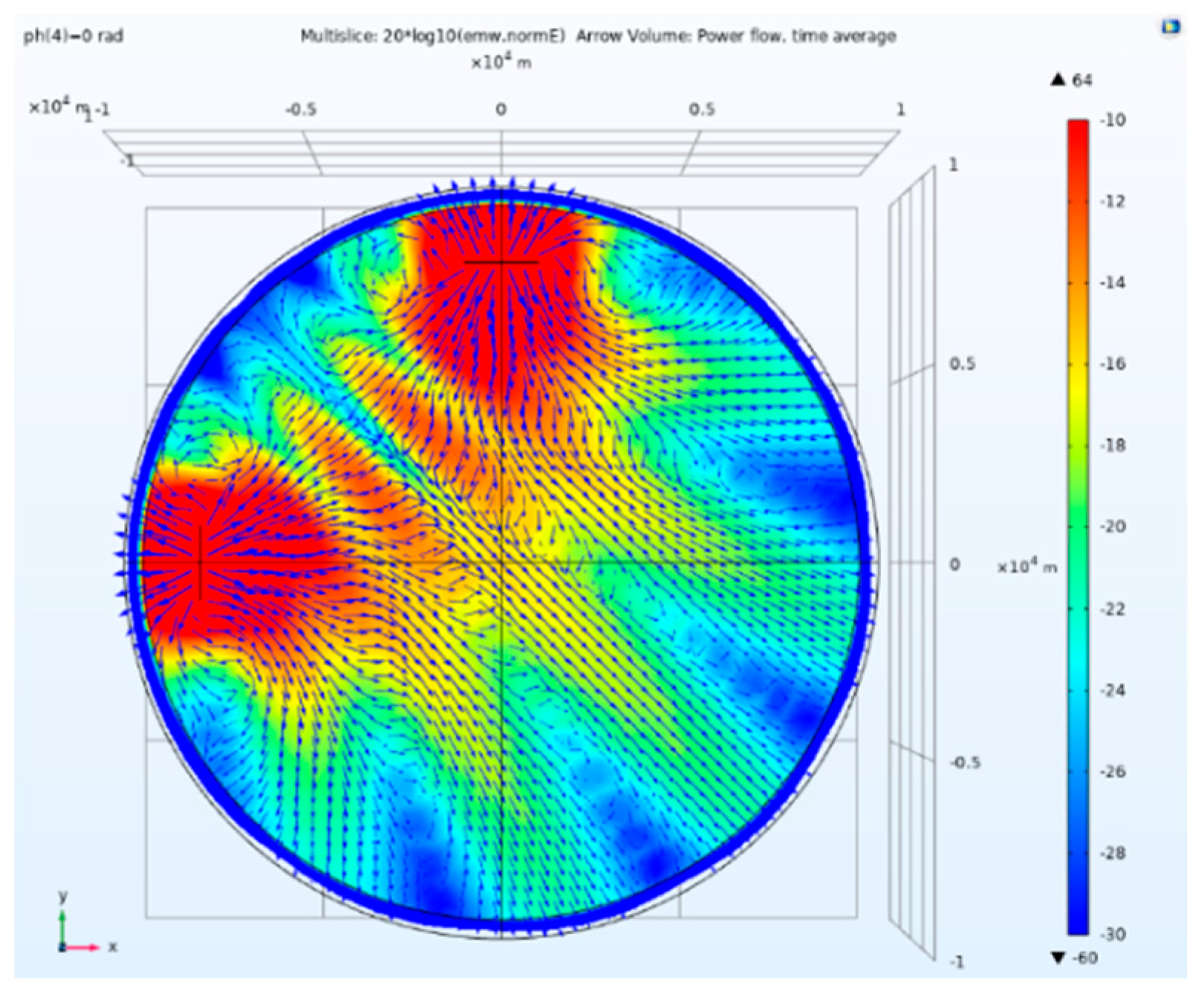

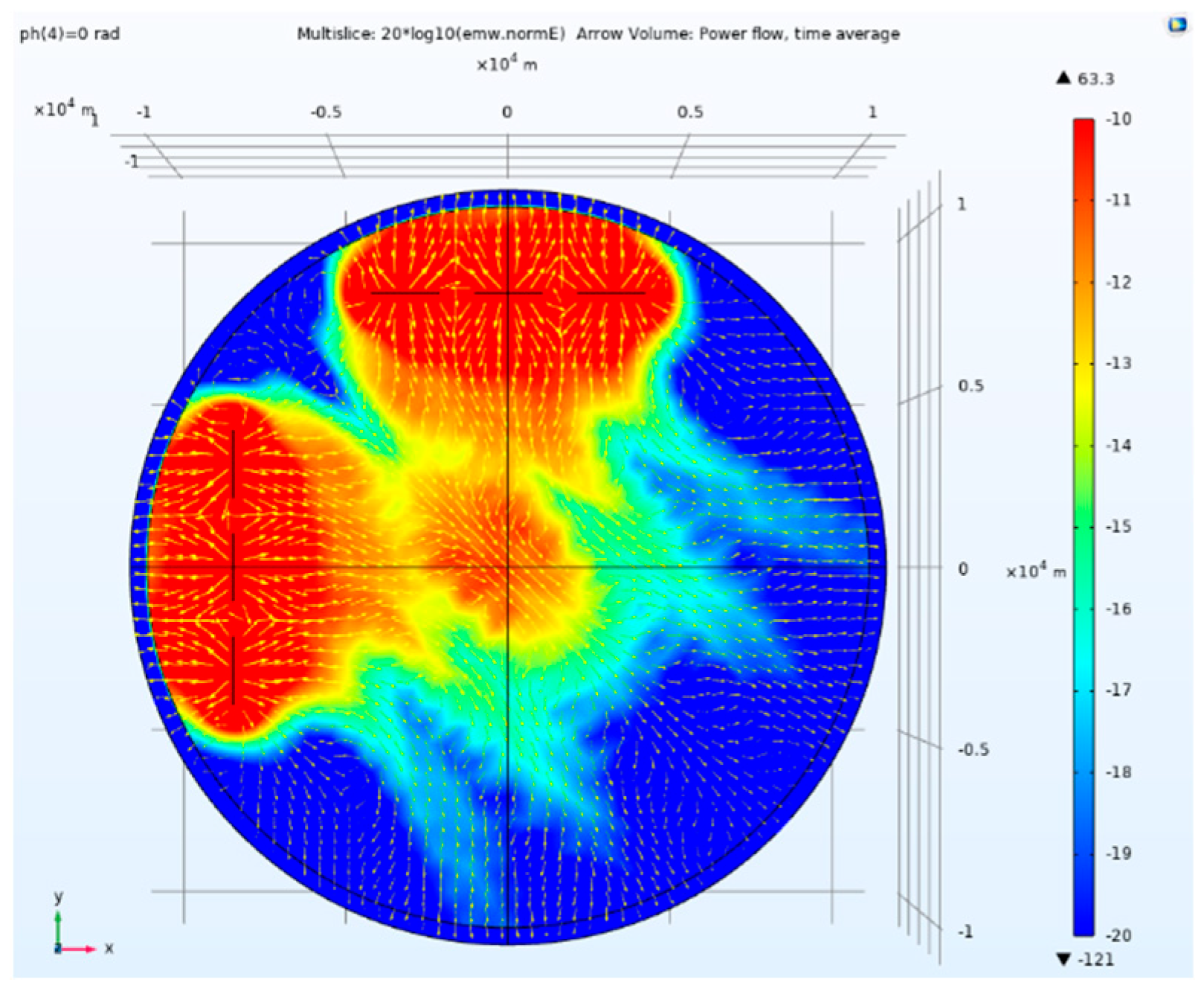

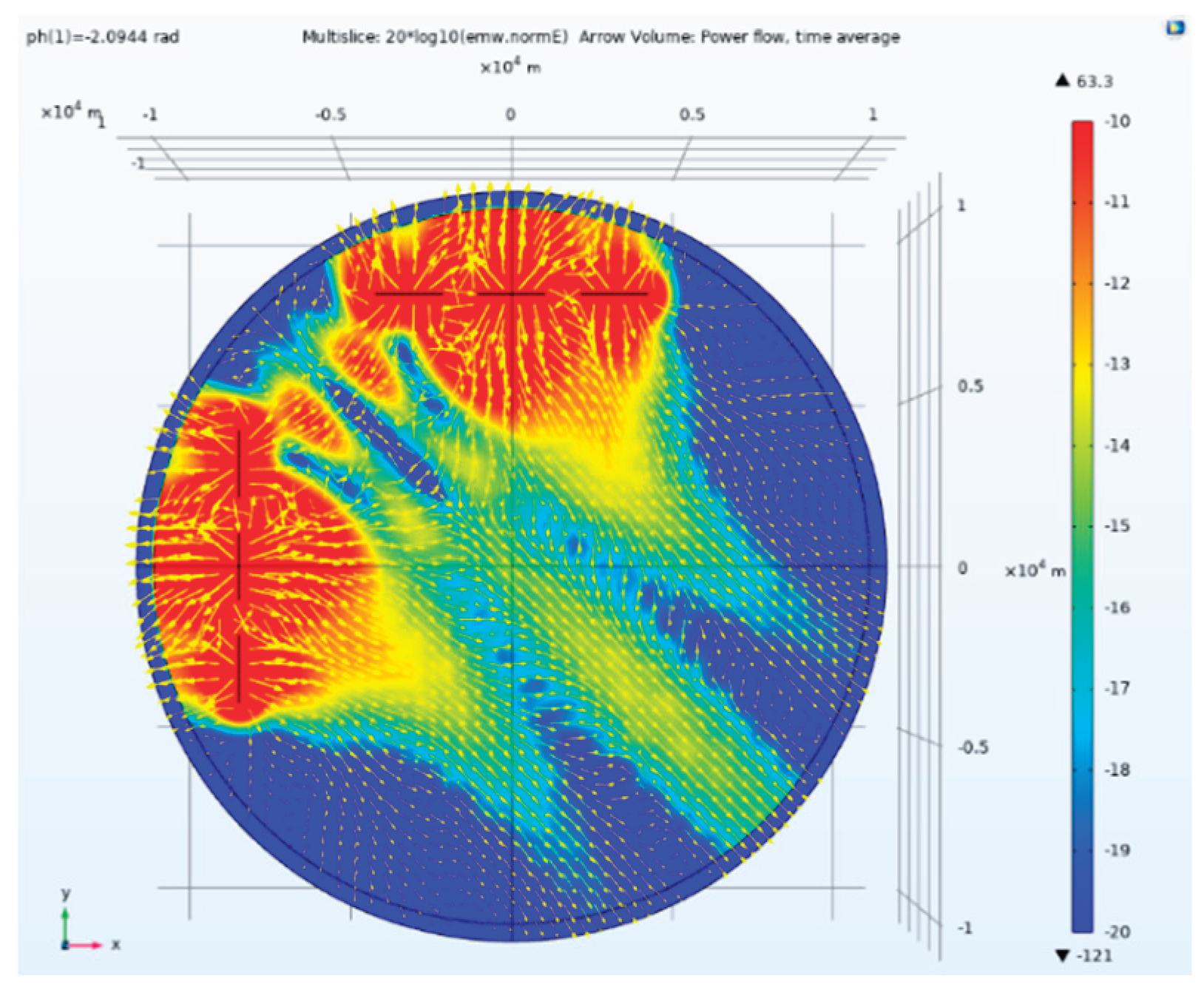

Figure 9.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of traditional separation tensor CSAMT.

Figure 9.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of traditional separation tensor CSAMT.

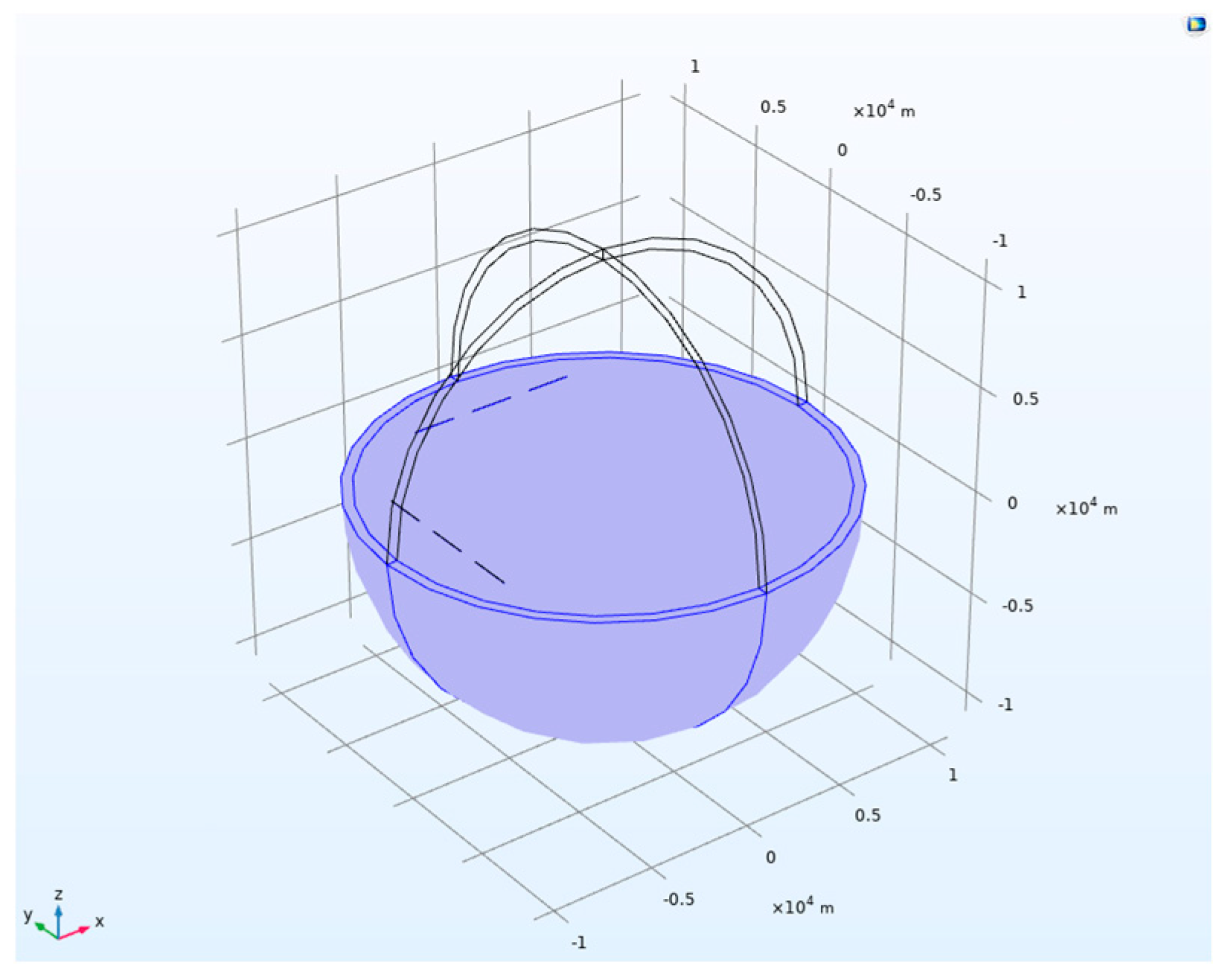

Figure 10.

Separation tensor CSAMT model based on L-type array artificial field source.

Figure 10.

Separation tensor CSAMT model based on L-type array artificial field source.

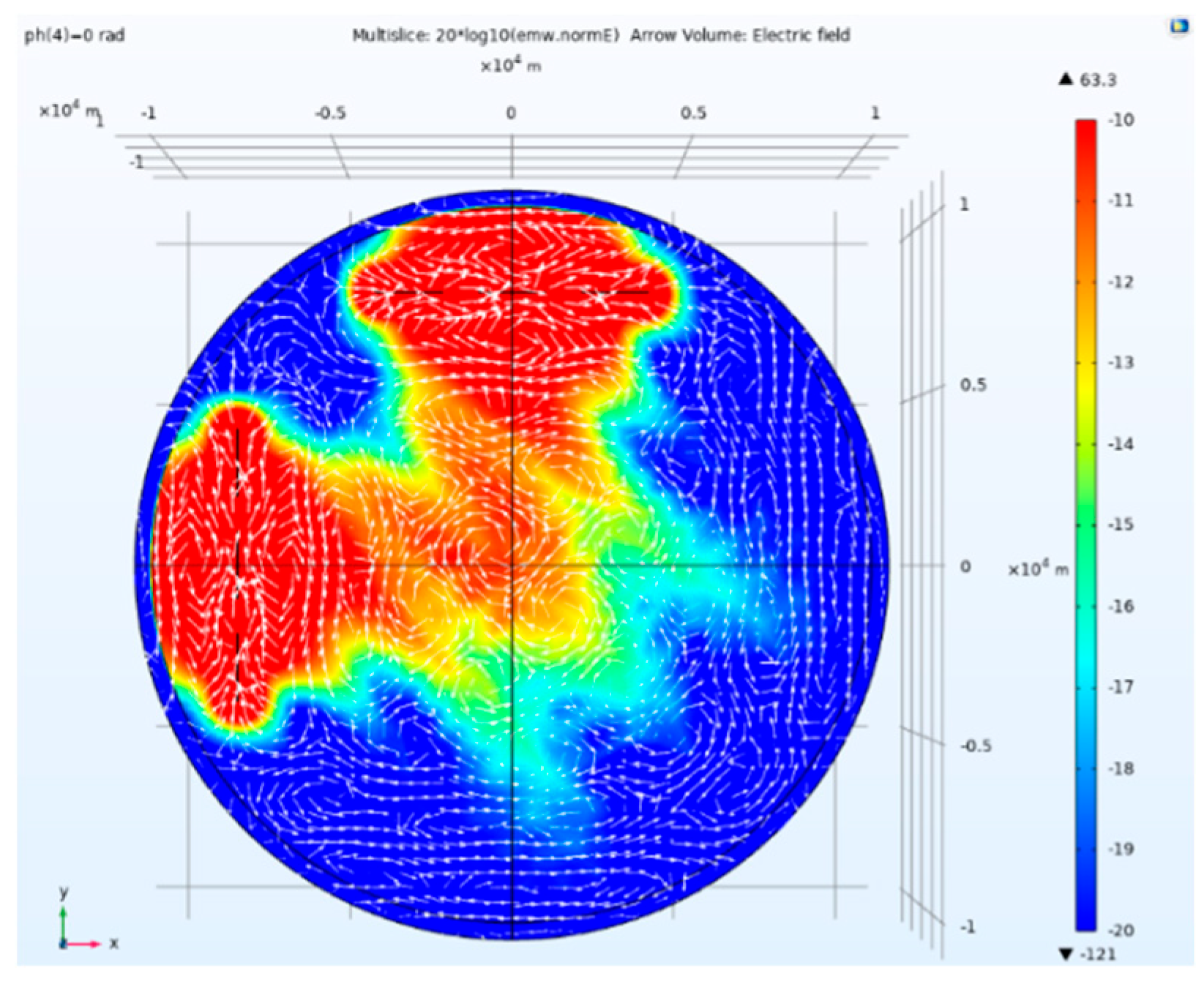

Figure 11.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under equal scale excitation.

Figure 11.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under equal scale excitation.

Figure 13.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under equal scale excitation.

Figure 13.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under equal scale excitation.

Figure 14.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation.

Figure 14.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation.

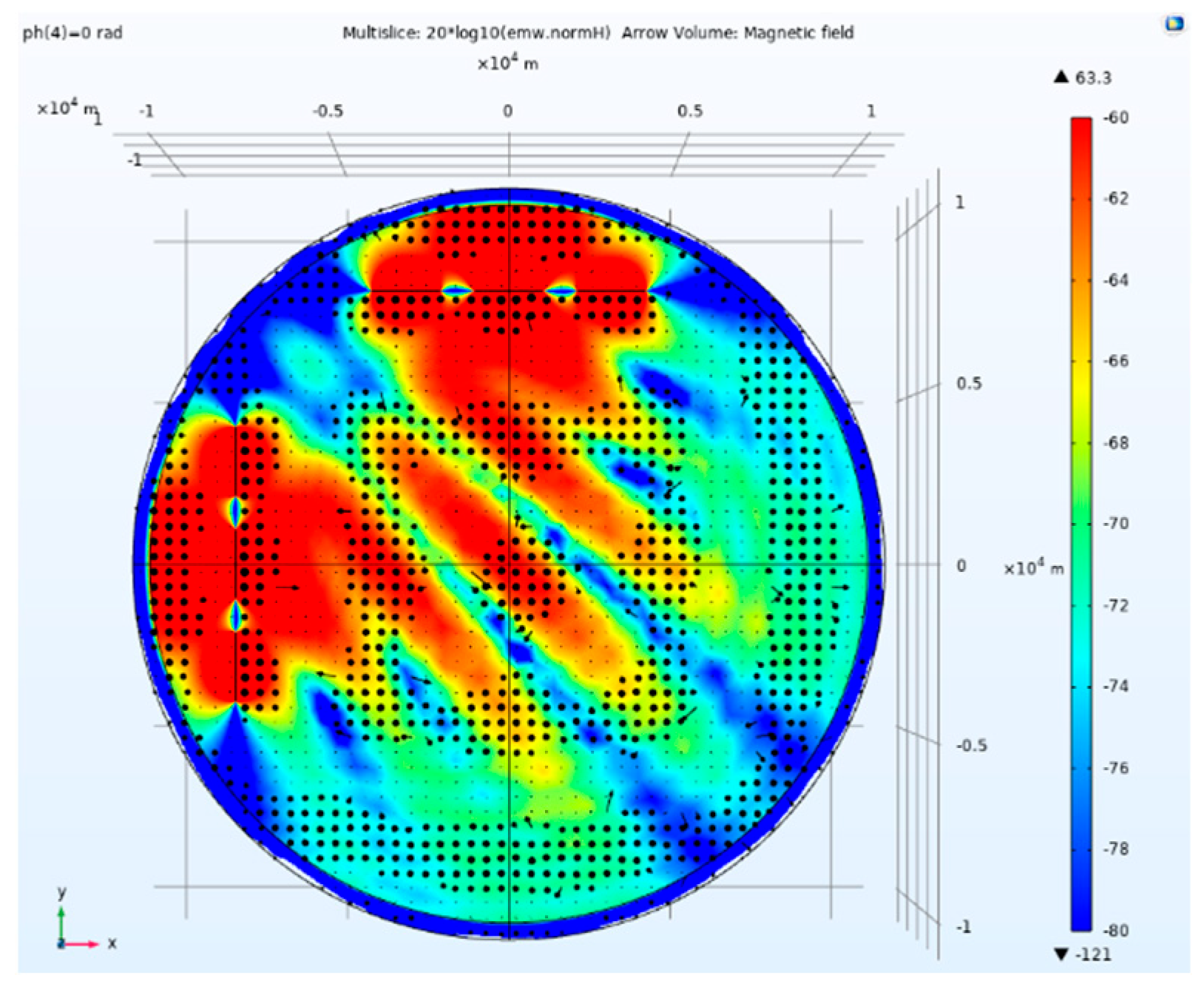

Figure 15.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation.

Figure 15.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation.

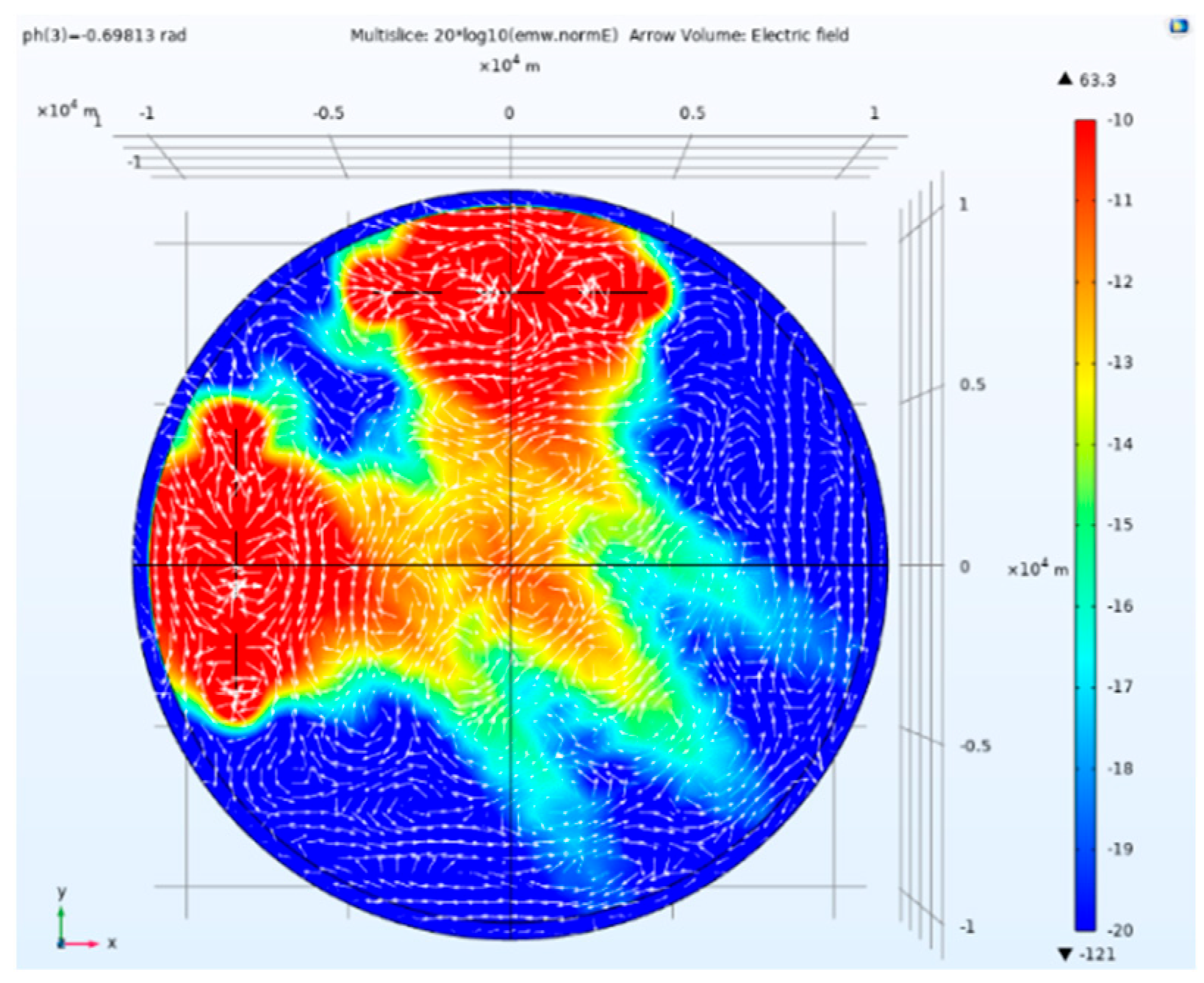

Figure 17.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference.

Figure 17.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference.

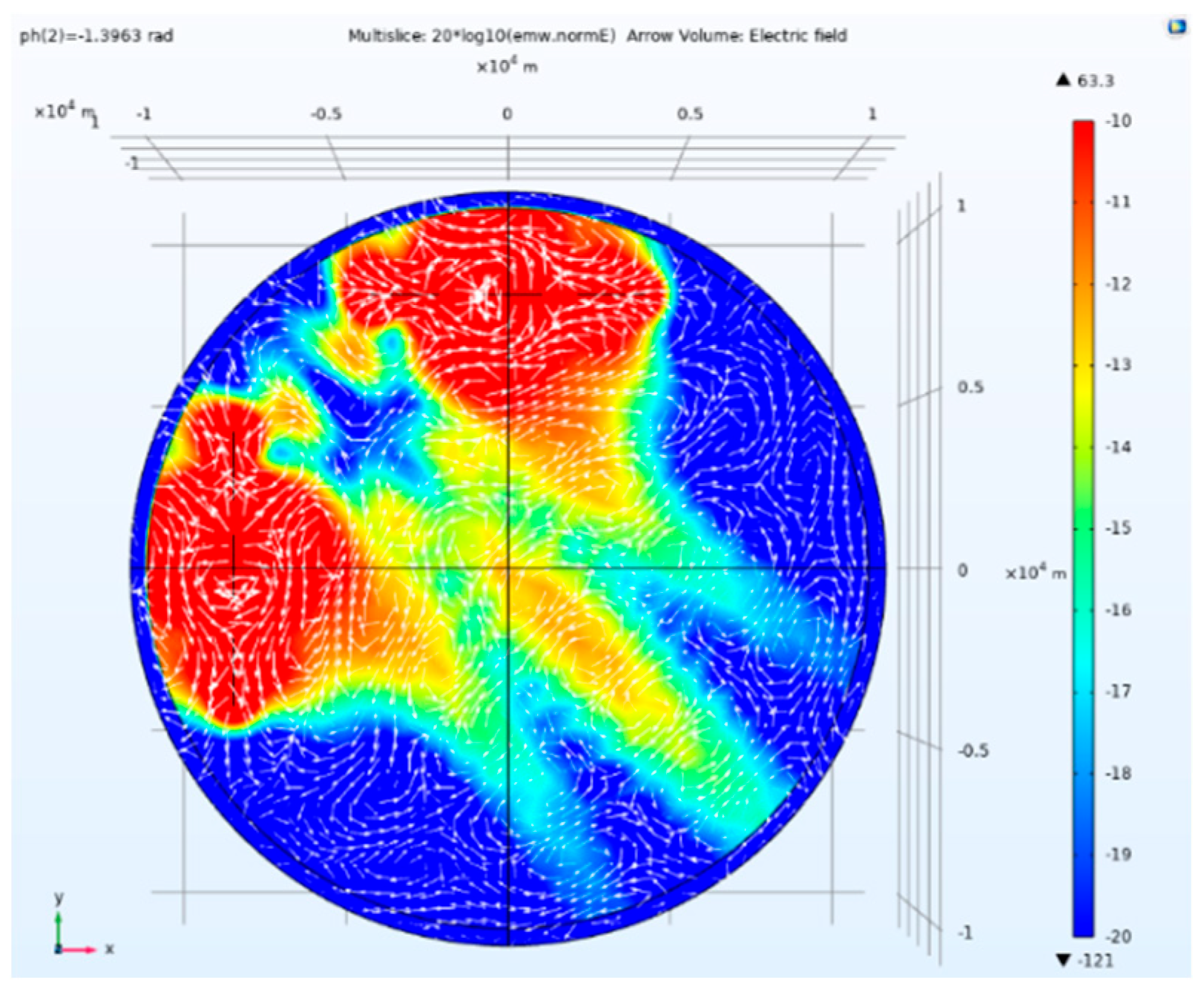

Figure 18.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 1.3963rad phase difference.

Figure 18.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 1.3963rad phase difference.

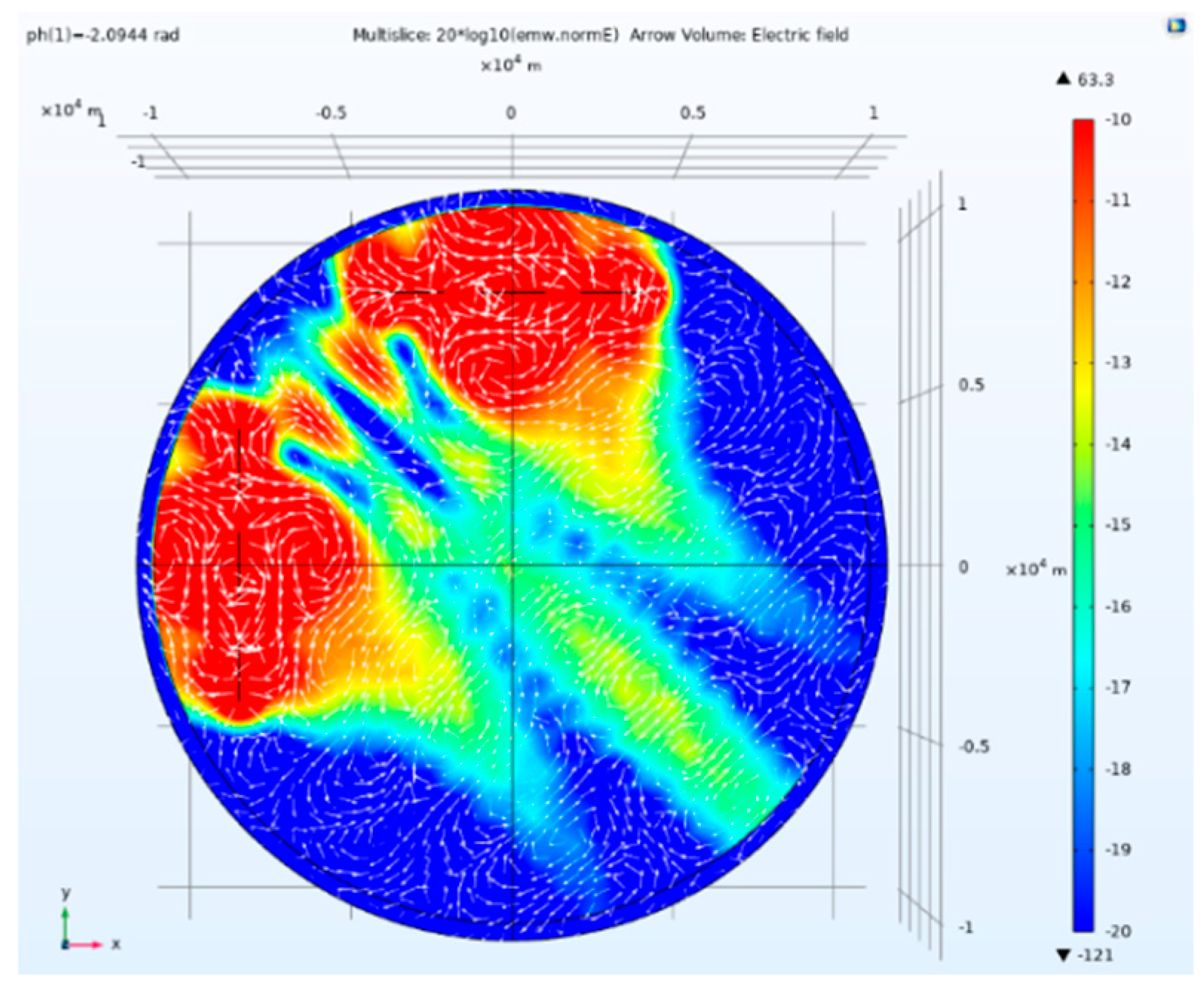

Figure 19.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 2.0944rad phase difference.

Figure 19.

Side view of electric field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 2.0944rad phase difference.

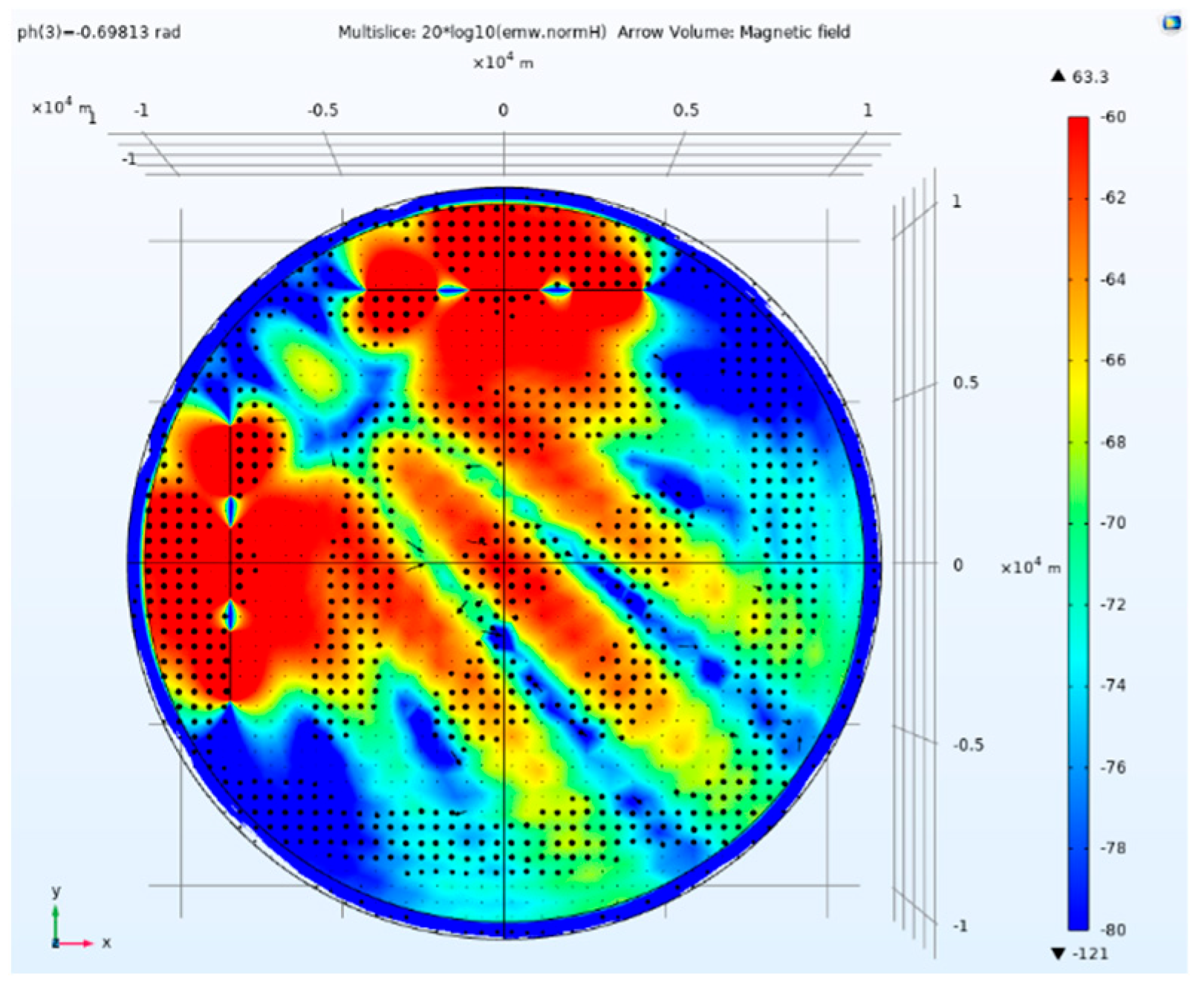

Figure 20.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference.

Figure 20.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference.

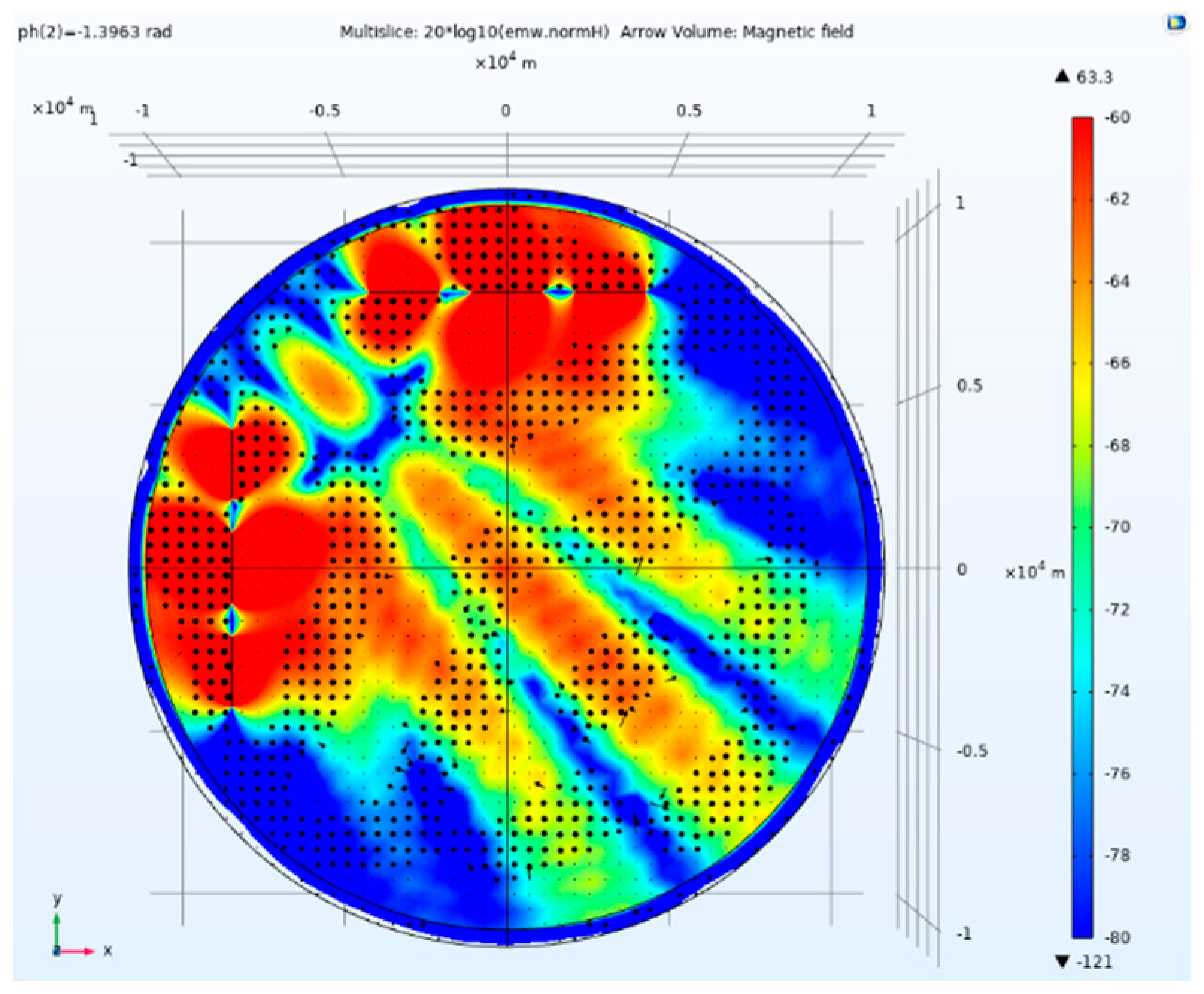

Figure 21.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 1.3963rad phase difference.

Figure 21.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 1.3963rad phase difference.

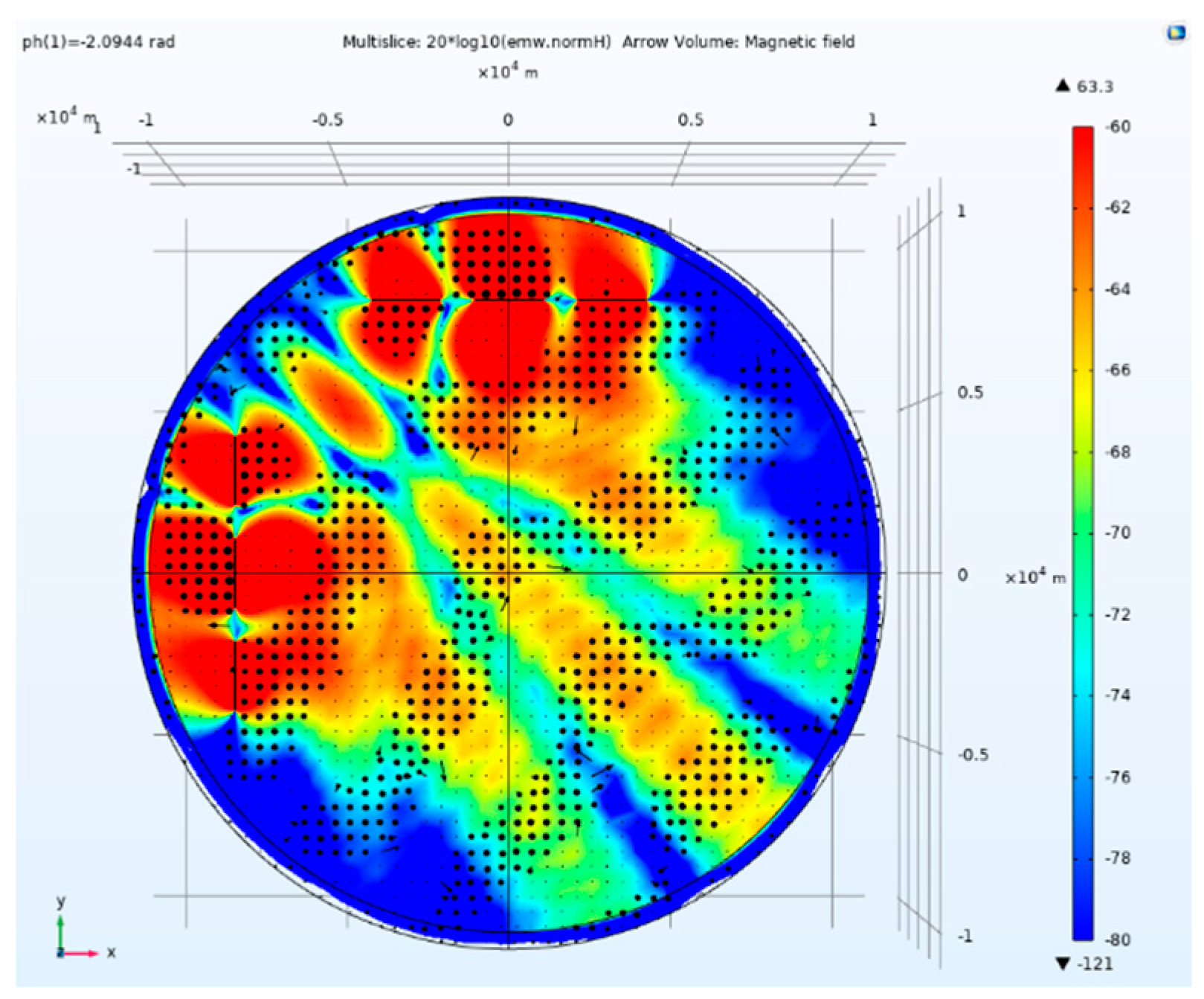

Figure 22.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 2.0944rad phase difference.

Figure 22.

Side view of magnetic field amplitude and direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 2.0944rad phase difference.

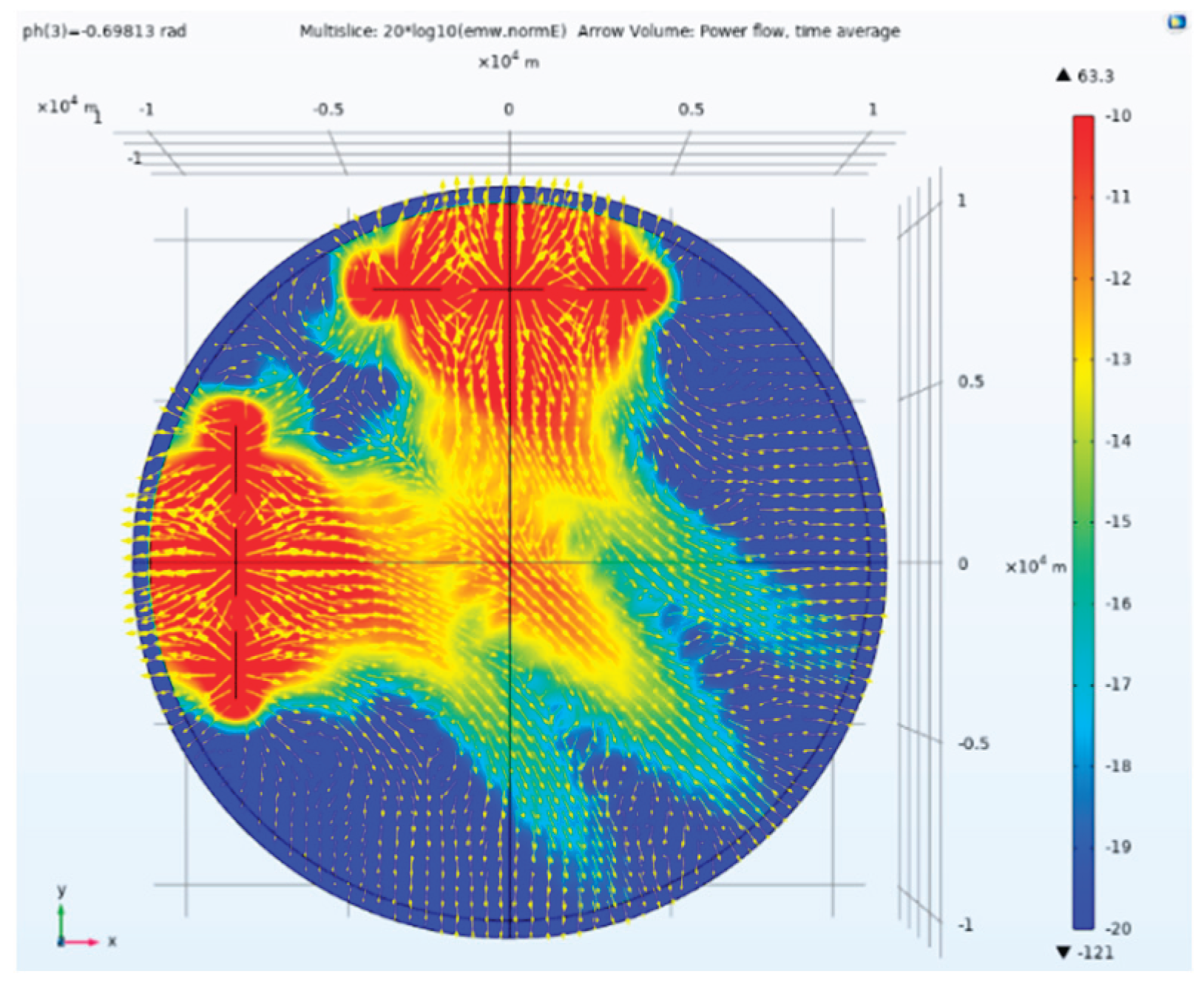

Figure 23.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference.

Figure 23.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference.

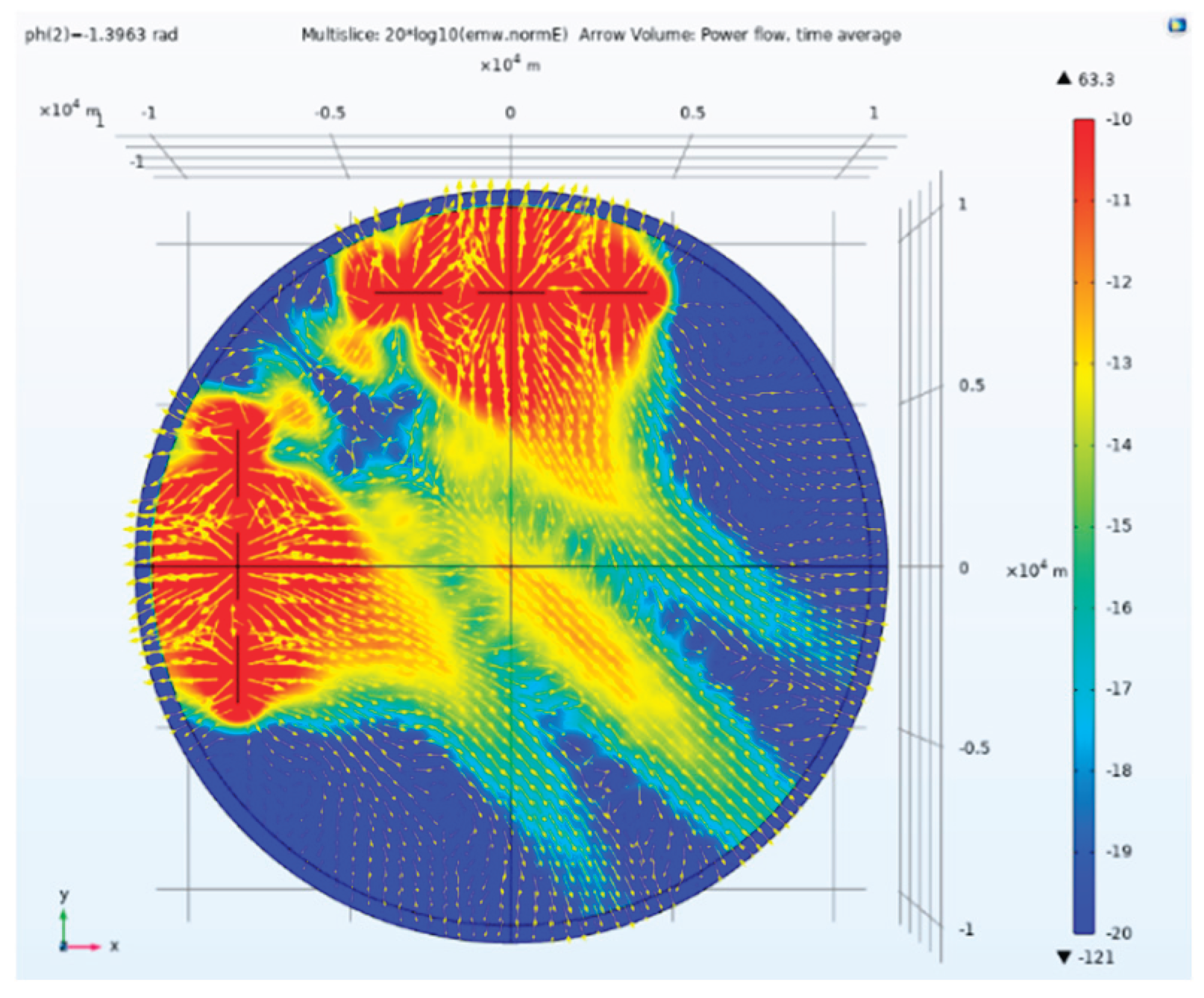

Figure 24.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference and 1.3963rad phase difference.

Figure 24.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference and 1.3963rad phase difference.

Figure 25.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference and 2.0944rad phase difference.

Figure 25.

Side view of electric field amplitude and Poynting vector direction of tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source under Taylor weighted excitation and 0.69813rad phase difference and 2.0944rad phase difference.

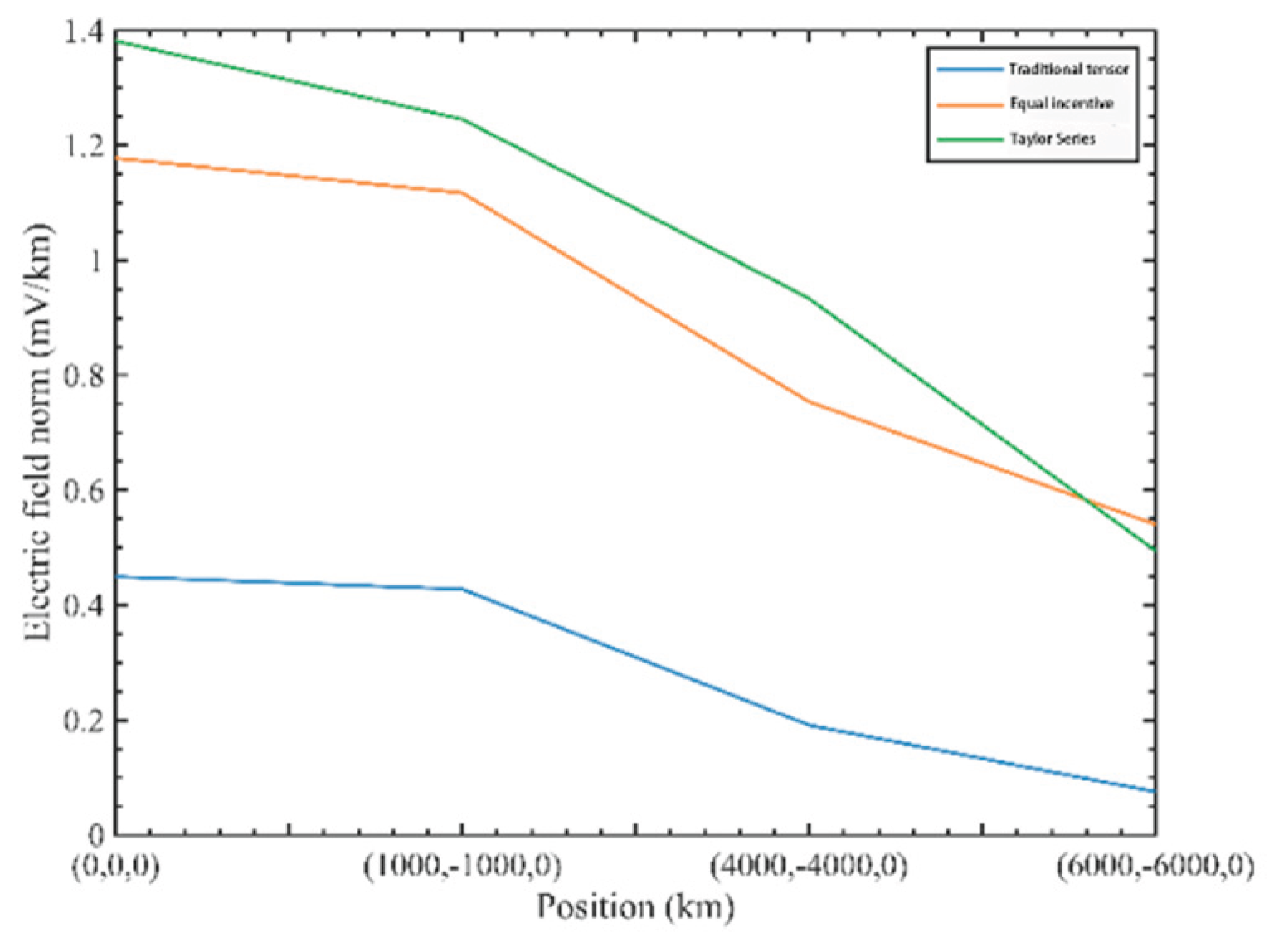

Figure 26.

Electric field amplitudes comparison of traditional tensor CSAMT, equal scale excitation and Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources.

Figure 26.

Electric field amplitudes comparison of traditional tensor CSAMT, equal scale excitation and Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources.

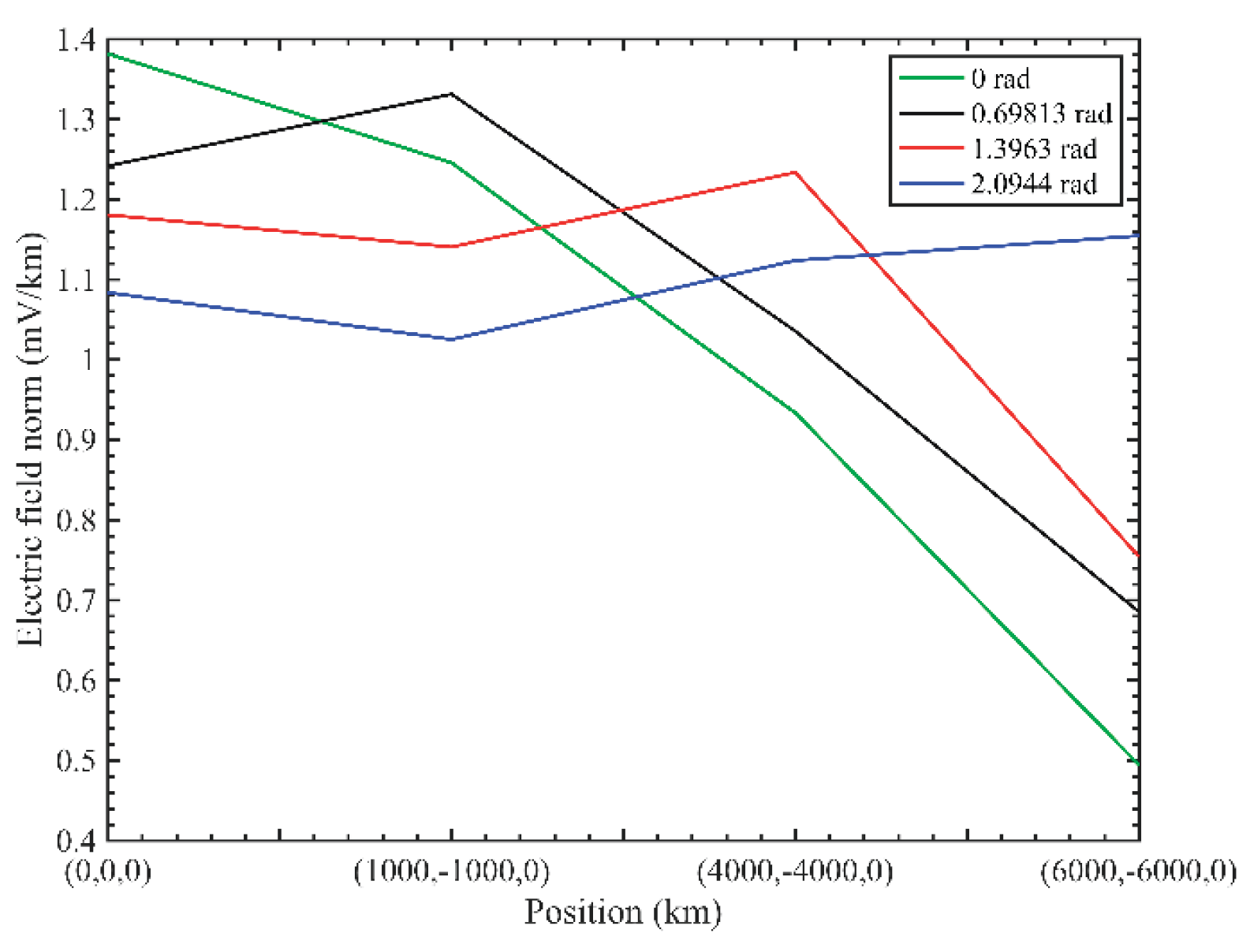

Figure 27.

Electric field amplitudes comparison of Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources under different phases.

Figure 27.

Electric field amplitudes comparison of Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources under different phases.

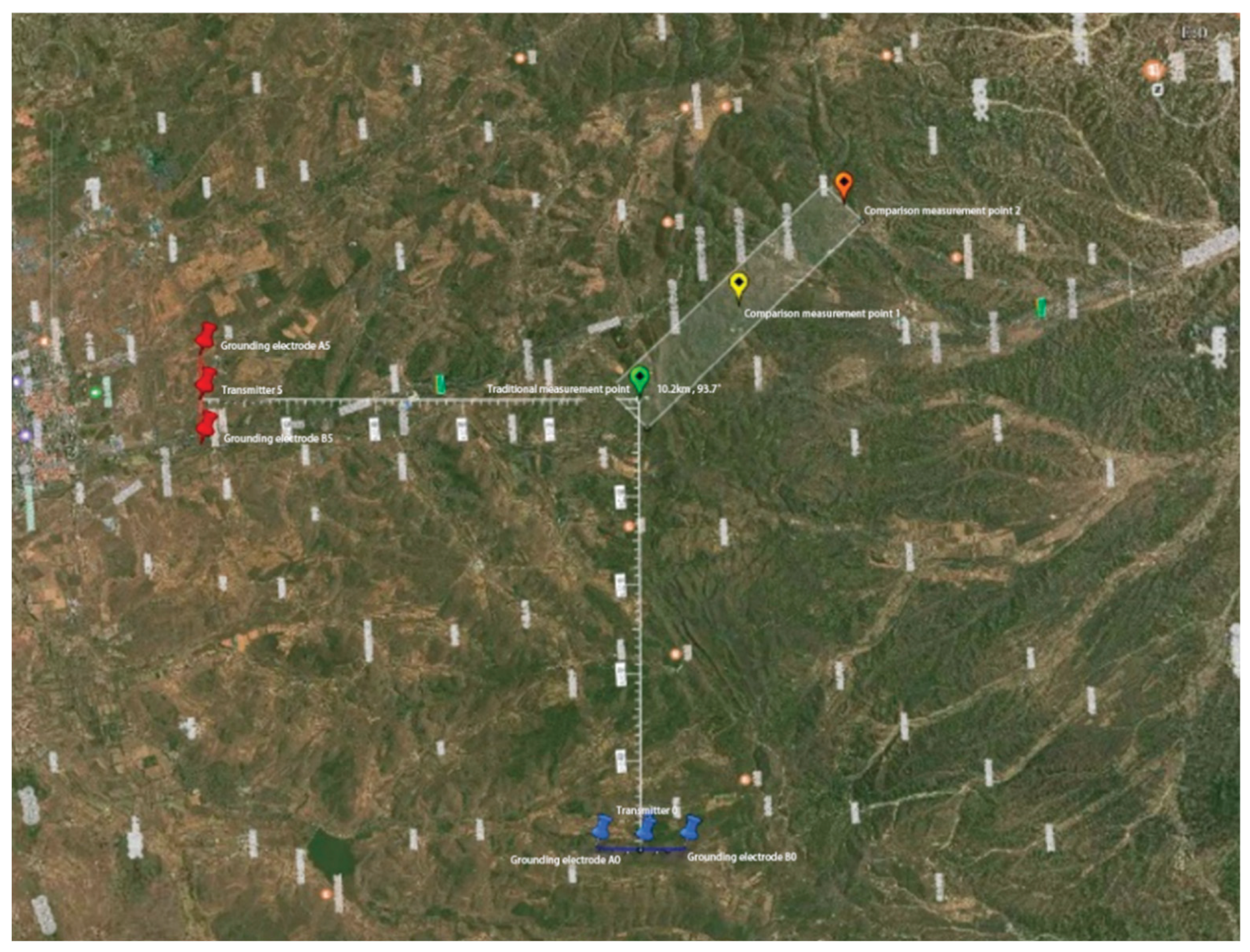

Figure 28.

Traditional separated tensor CSAMT.

Figure 28.

Traditional separated tensor CSAMT.

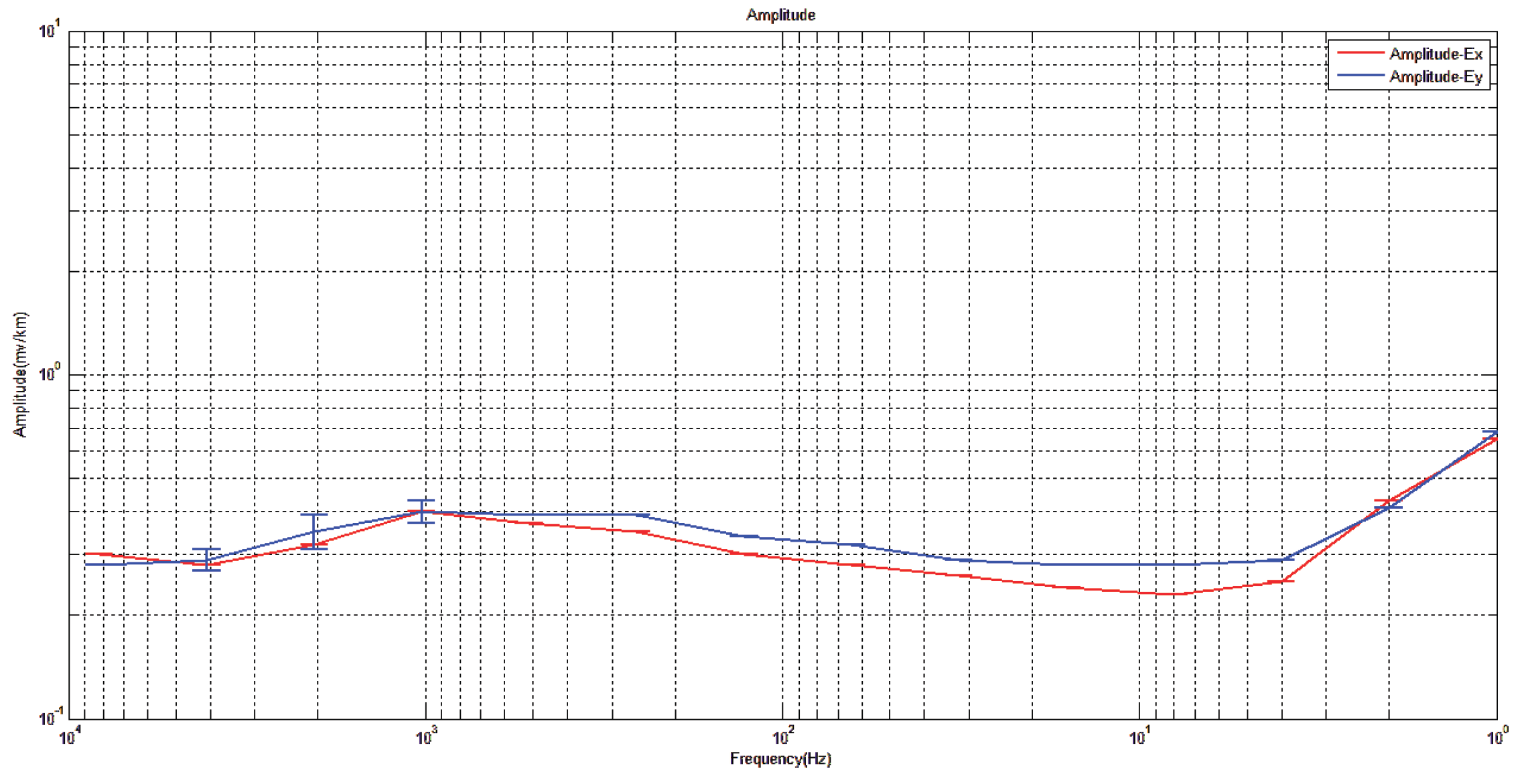

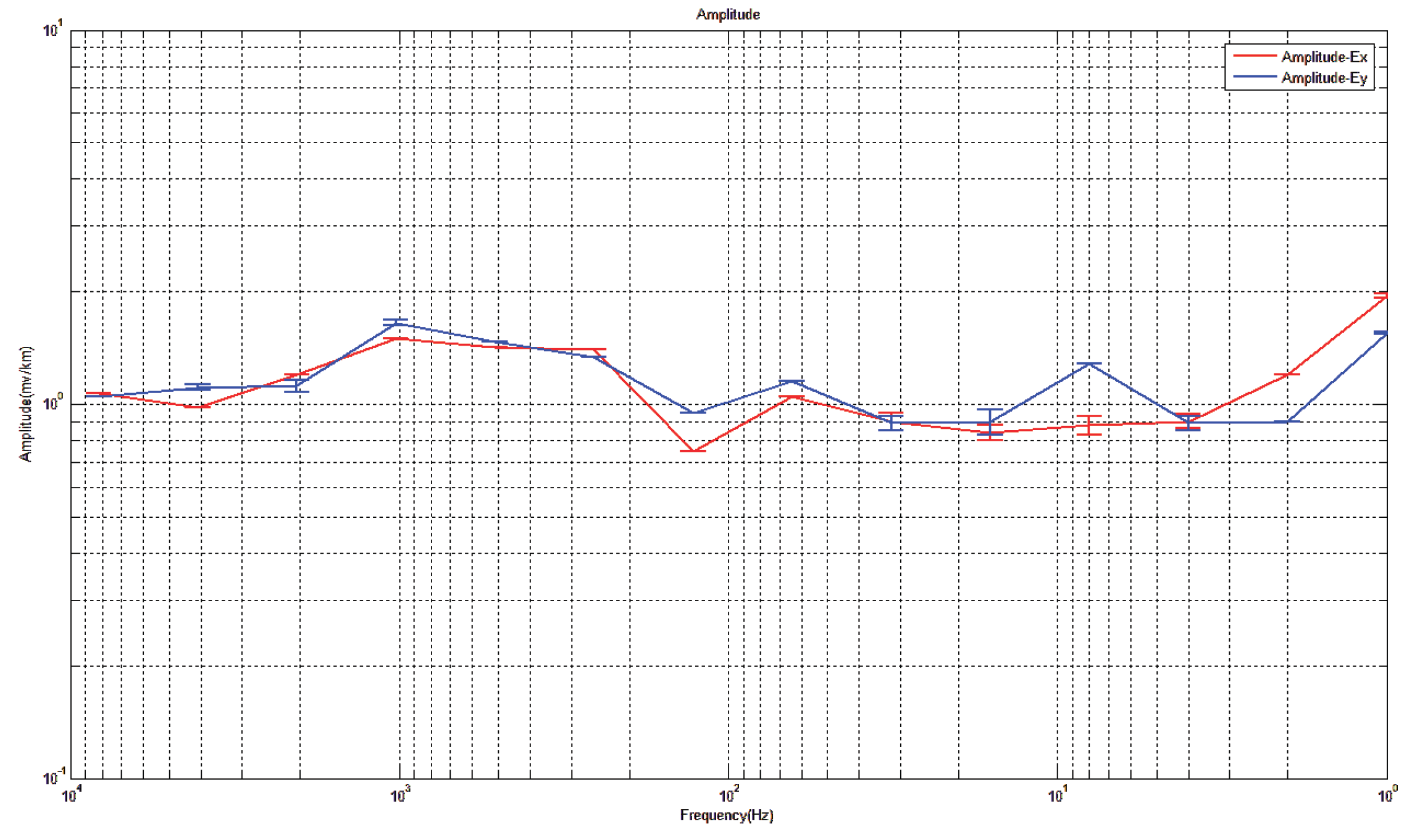

Figure 29.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of traditional measuring point.

Figure 29.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of traditional measuring point.

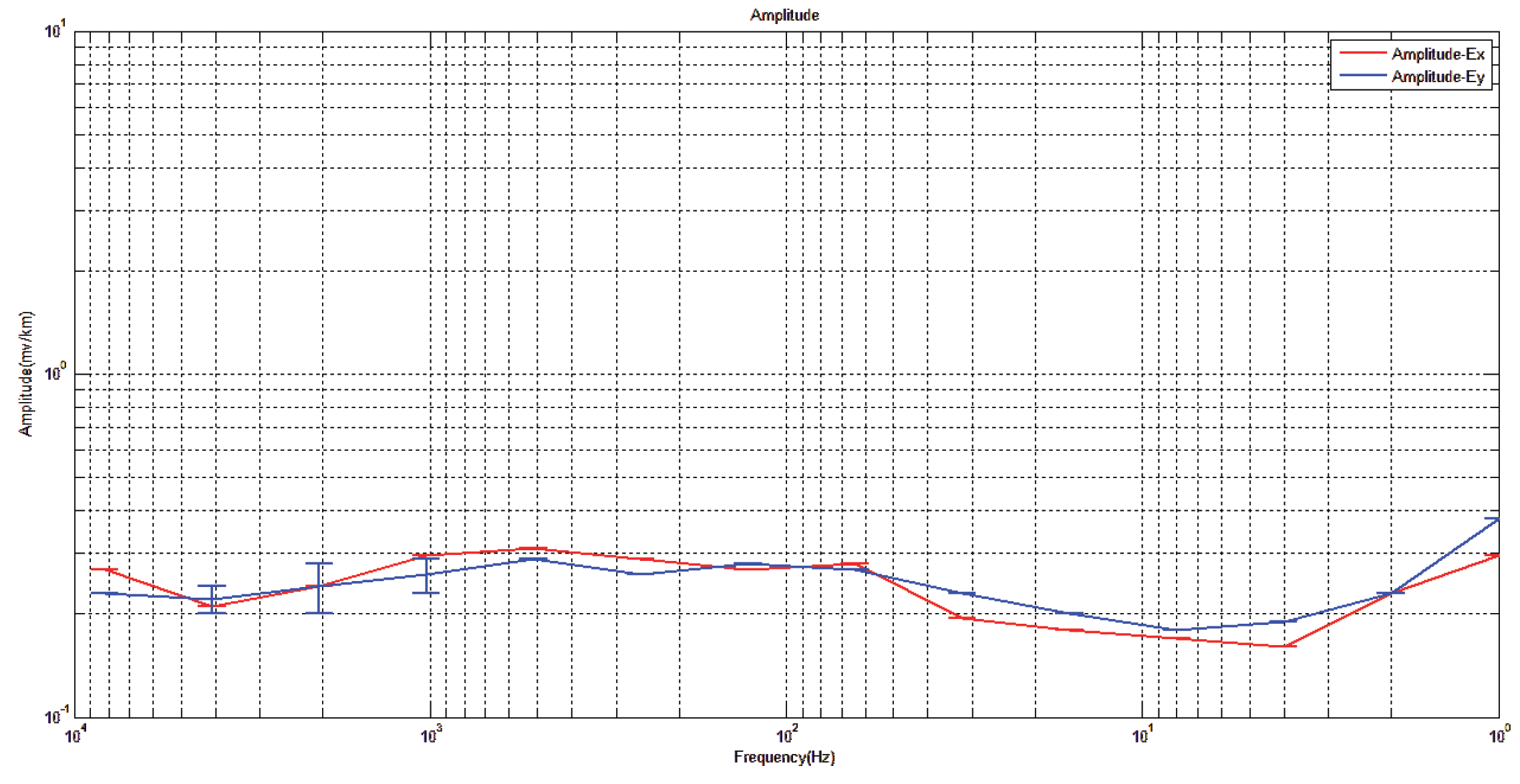

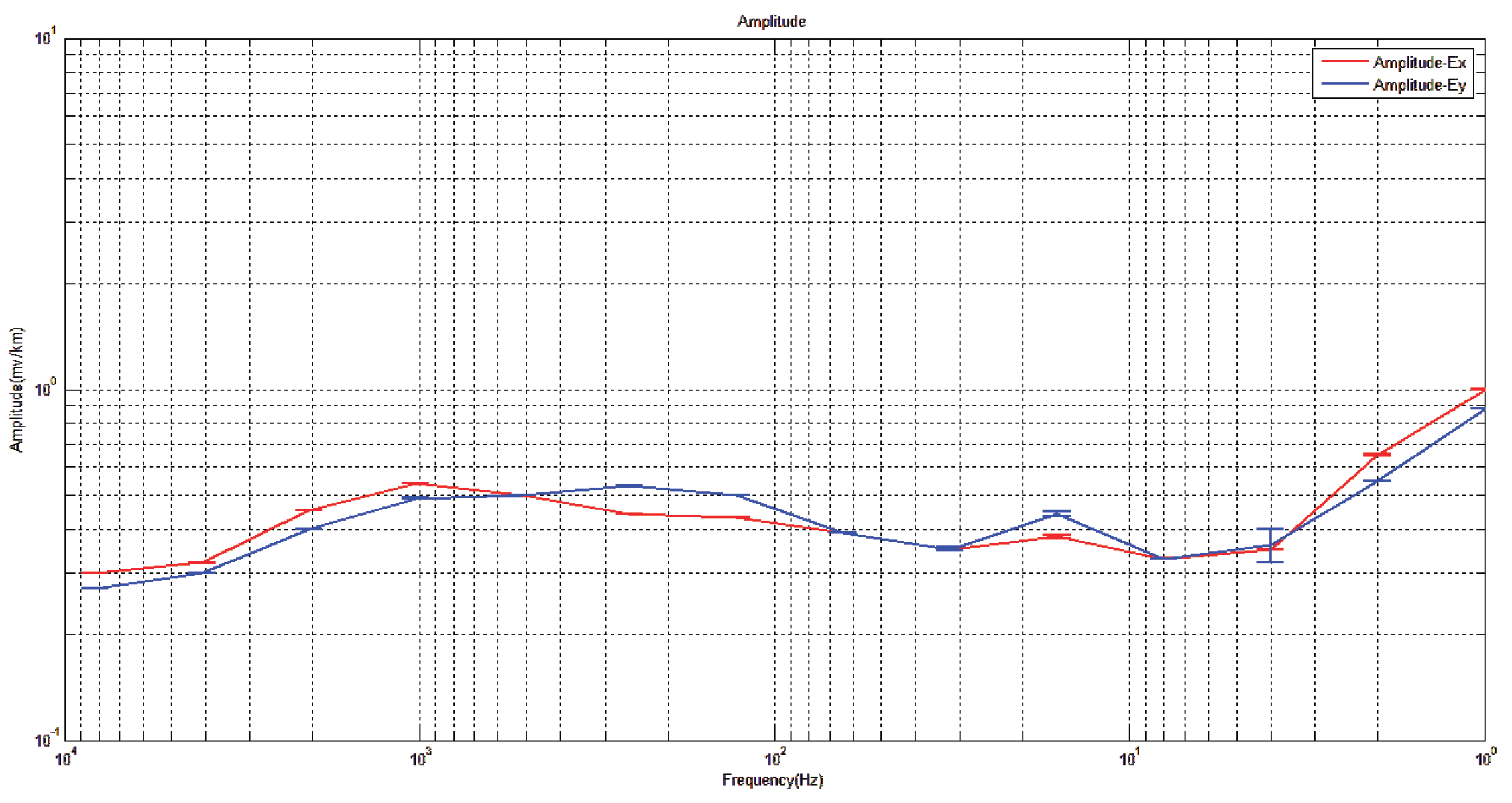

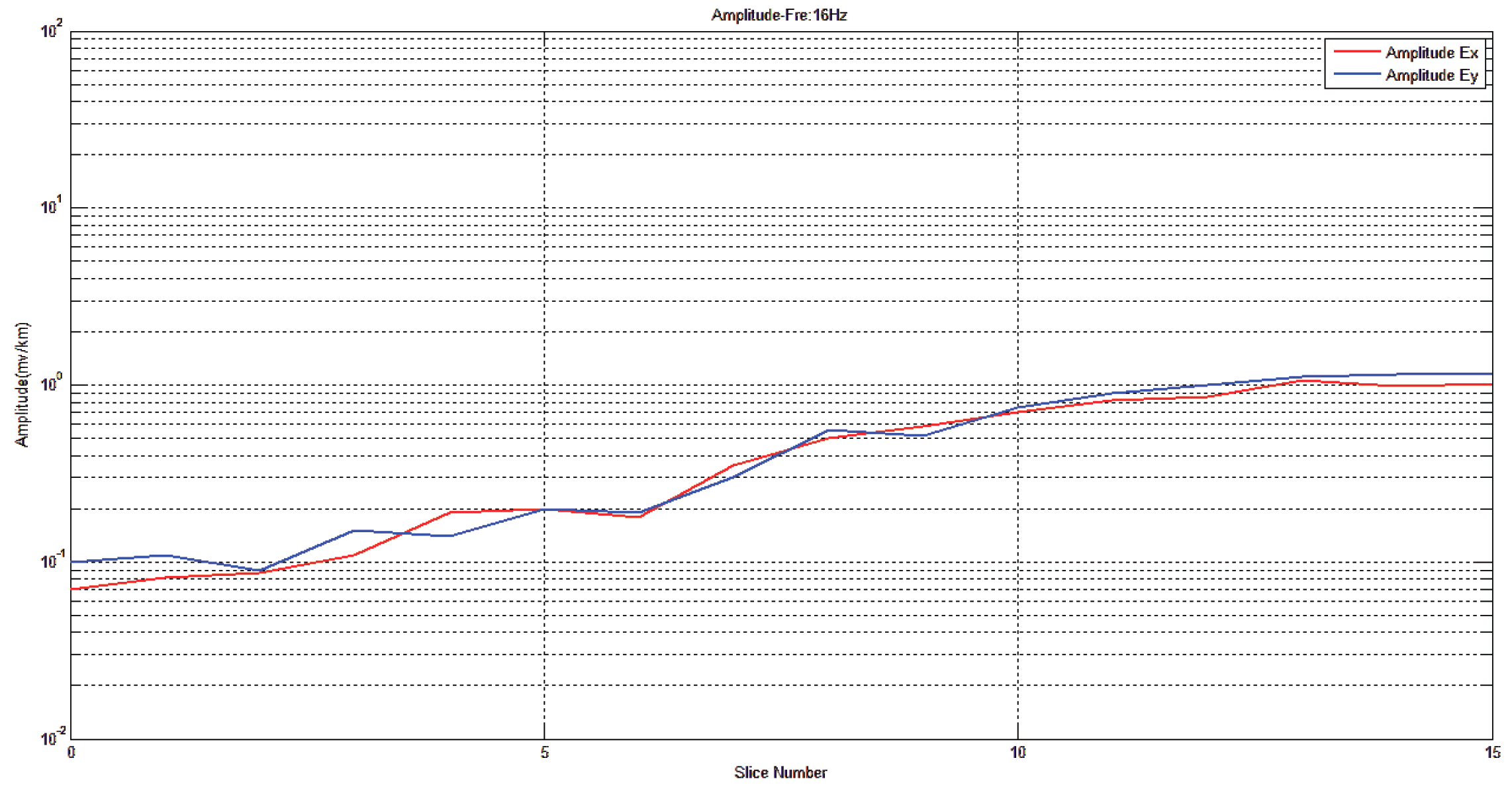

Figure 30.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 1 for comparison.

Figure 30.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 1 for comparison.

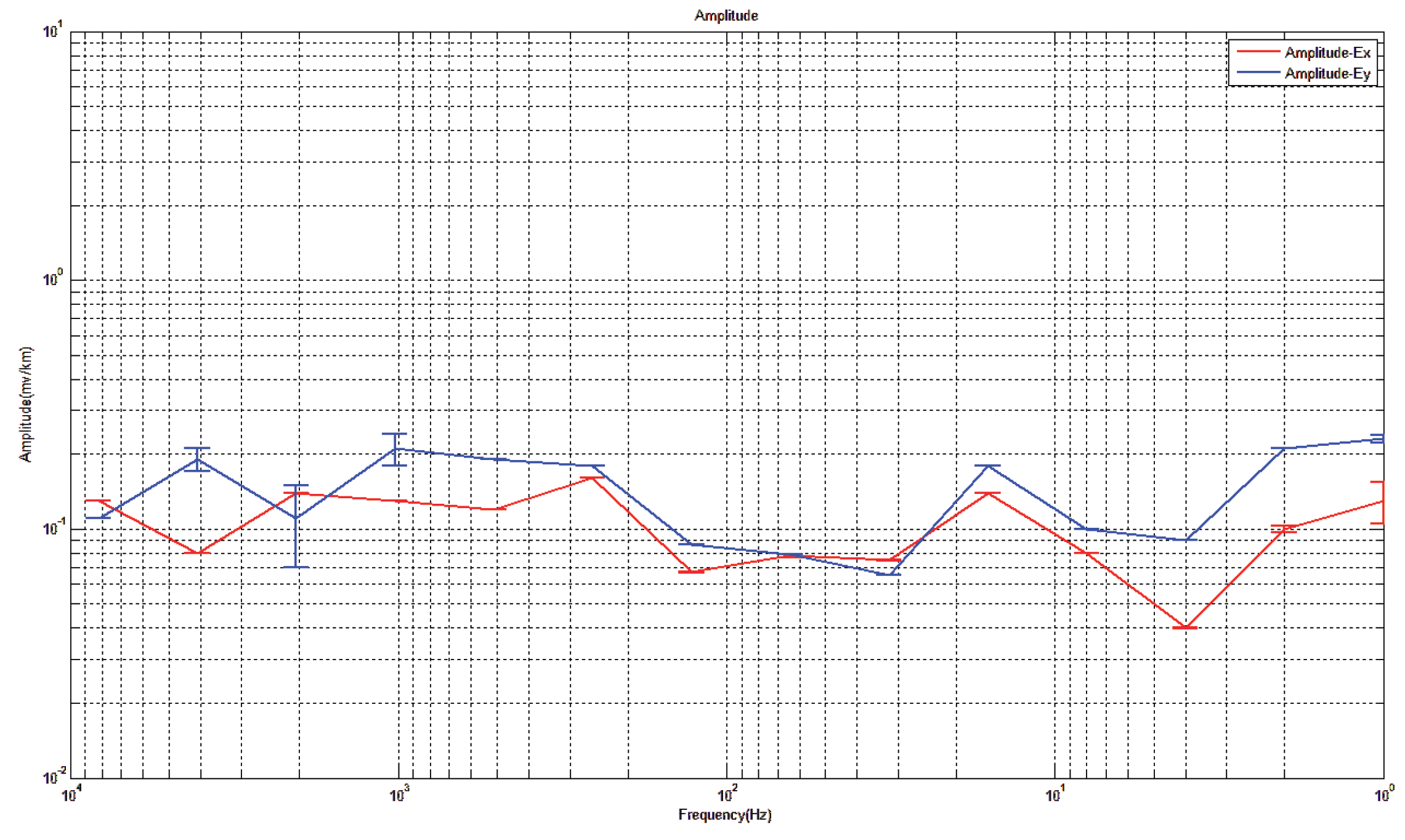

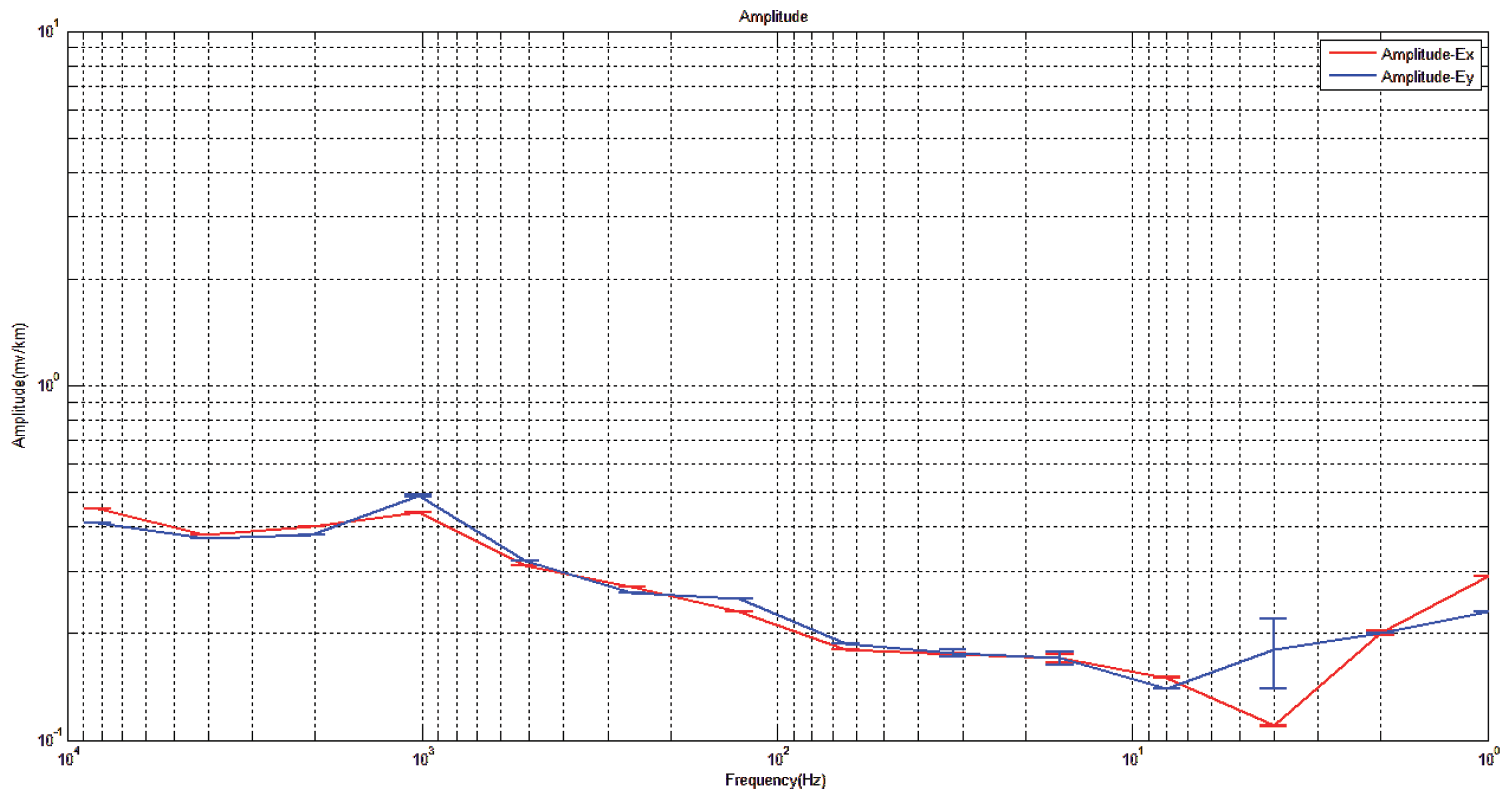

Figure 31.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 2 for comparison.

Figure 31.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 2 for comparison.

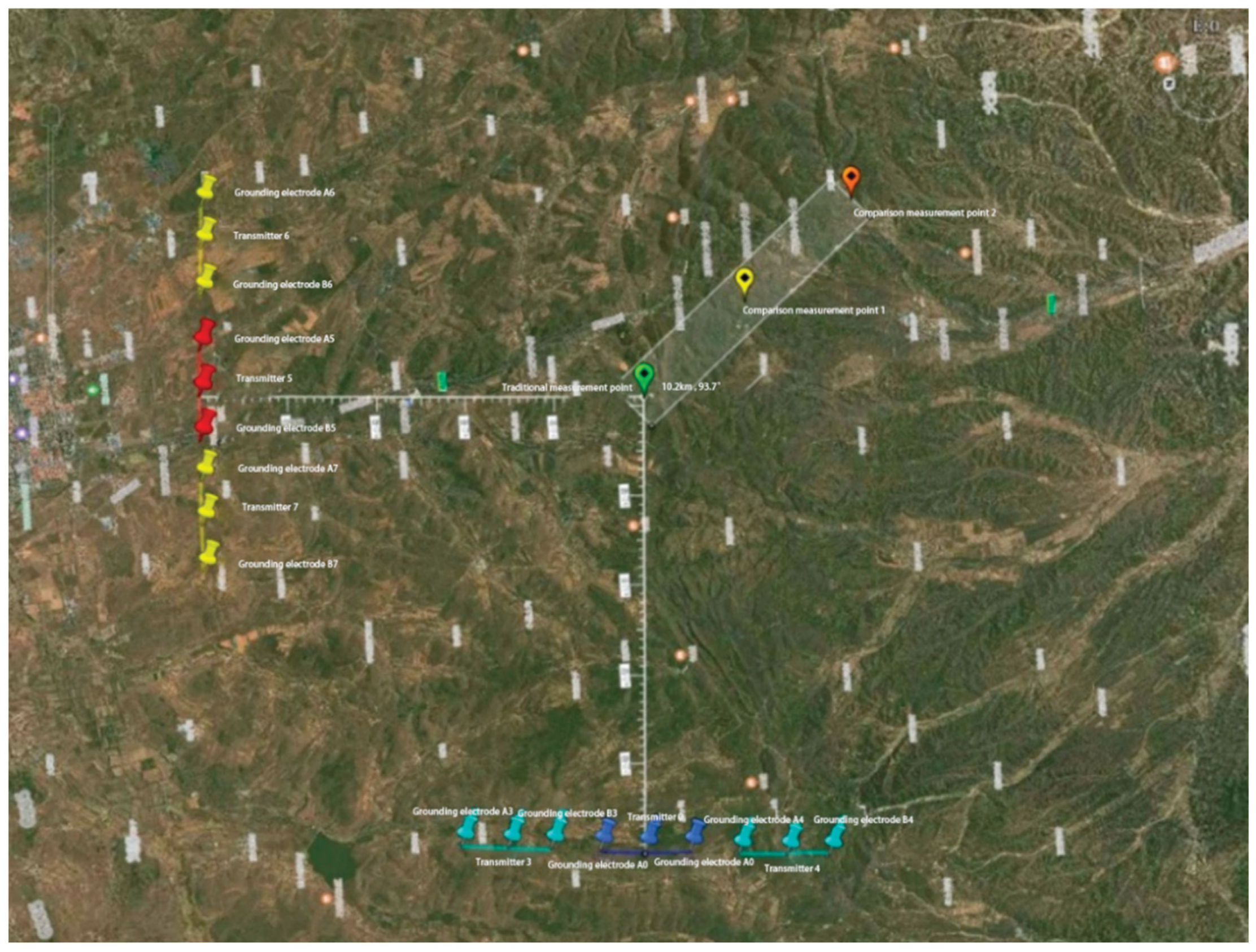

Figure 32.

Tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source.

Figure 32.

Tensor CSAMT based on L-type array artificial field source.

Figure 33.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of traditional measuring point (after pattern synthesis).

Figure 33.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of traditional measuring point (after pattern synthesis).

Figure 34.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 1 for comparison (after pattern synthesis).

Figure 34.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 1 for comparison (after pattern synthesis).

Figure 35.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 2 for comparison (after pattern synthesis).

Figure 35.

Electric field amplitude in x and y directions of measuring point 2 for comparison (after pattern synthesis).

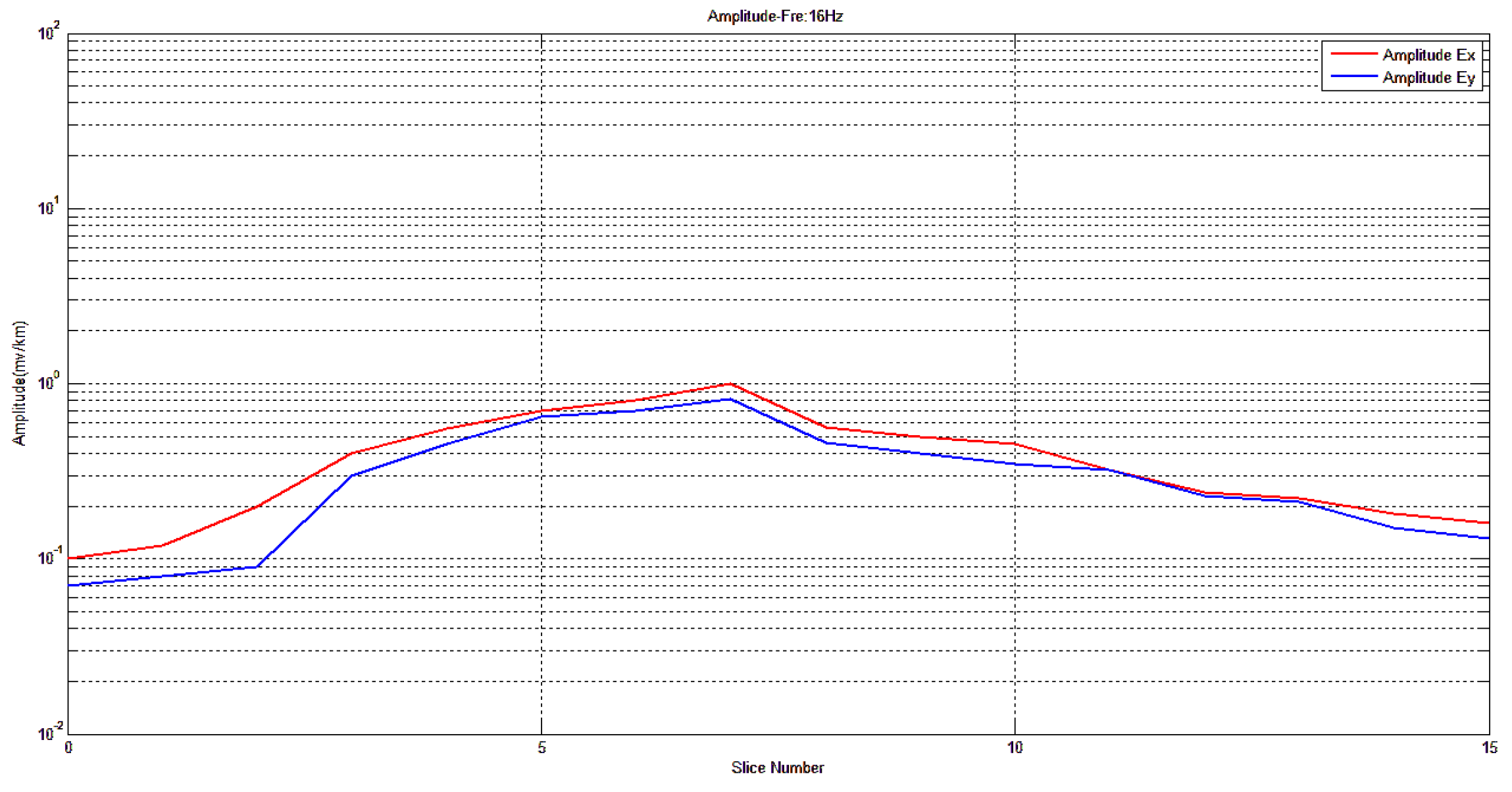

Figure 36.

Electric field amplitude in x and y direction of measuring point 1 for comparison (after adaptive beamforming).

Figure 36.

Electric field amplitude in x and y direction of measuring point 1 for comparison (after adaptive beamforming).

Figure 37.

Electric field amplitude in x and y direction of measuring point 2 for comparison (after adaptive beamforming).

Figure 37.

Electric field amplitude in x and y direction of measuring point 2 for comparison (after adaptive beamforming).

Table 1.

Arithmetic Pd for the different lumped ports, identified by their lumped port name.

Table 1.

Arithmetic Pd for the different lumped ports, identified by their lumped port name.

| Arithmetic Phase Difference |

Coaxial Resonator Linear Array Lumped Port |

| 0 [rad] |

Port1 |

| ph range(-0.69813, 0.69813, -2.0944 [rad]) |

Port2 |

| 2*ph [rad] |

Port3 |

Table 2.

Electric field amplitudes(mV/km) comparison of traditional tensor CSAMT, equal scale excitation and Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources.

Table 2.

Electric field amplitudes(mV/km) comparison of traditional tensor CSAMT, equal scale excitation and Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources.

| |

(0, 0, 0) |

(1000, -1000, 0) |

(4000, -4000, 0) |

(6000, -6000, 0) |

| Traditional tensor |

0.44965 |

0.42756 |

0.19111 |

0.07511 |

| Equal incentive |

1.17781 |

1.11731 |

0.75391 |

0.54028 |

| Taylor Series |

1.38158 |

1.24552 |

0.93365 |

0.49438 |

Table 3.

Electric field amplitudes(mV/km) comparison of Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources under different phases.

Table 3.

Electric field amplitudes(mV/km) comparison of Taylor weighted based on the separation tensor CSAMT of L-type array artificial field sources under different phases.

| |

(0, 0, 0) |

(1000, -1000, 0) |

(4000, -4000, 0) |

(6000, -6000, 0) |

| 0rad |

1.38158 |

1.24552 |

0.93365 |

0.49438 |

| 0.69813rad |

1.24177 |

1.33122 |

1.03575 |

0.68539 |

| 1.3963rad |

1.18064 |

1.14057 |

1.23365 |

0.75419 |

| 2.0944rad |

1.08377 |

1.02522 |

1.12376 |

1.15455 |