1. Introduction

1.1. The Global Construction Sector and Its Carbon Footprint

The construction industry represents one of the most significant contributors to global carbon emissions, accounting for a substantial portion of worldwide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across the complete lifecycle of built assets. Recent evidence indicates that the built environment is responsible for approximately 38-40% of global GHG emissions when considering the full life cycle, encompassing embodied carbon in materials, construction activities, operational energy use, and end-of-life processes [

1,

2]. This substantial contribution highlights the sector’s crucial role in global decarbonisation efforts and underscores the urgent need for comprehensive carbon assessment methodologies.

Moreover, the construction sector places great importance on embodied carbon (EC), which refers to the greenhouse gas emissions that occur throughout the life cycle of a building, including manufacturing, construction, maintenance, and dismantling. Even new and energy-efficient buildings can have up to 50% of their carbon footprint attributed to EC, making it responsible for approximately 10% of global energy-related CO2 emissions [

3]. Therefore, reducing EC is crucial for achieving sustainability and climate goals [

4]. EC calculations are vital for developing countries like Sri Lanka for several reasons. The results of these calculations provide crucial insight into the environmental impact of construction projects [

5]. Construction plays a pivotal role in Sri Lanka’s dynamic landscape, marked by rapid economic growth [

6]. Thus, to mitigate environmental harm, it is essential to understand the concept of EC. Further, Sri Lanka can effectively reduce emissions by quantifying the amount of EC, thereby promoting sustainable development. Additionally, there is an increasing emphasis on environmentally responsible projects, as mandated by international agreements and investors, as well as commercial buildings, hotels, and apartments [

7].

1.2. The Sri Lankan Construction Sector: Economic Significance and Environmental Imperatives

In Sri Lanka, the construction industry is crucial to the economy and also contributes significantly to the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. The sector has consistently made a significant contribution to GDP, usually between 6% and 7% over the past decade [

8].

From an environmental standpoint, the Sri Lankan construction sector has a significant impact on national emissions through embodied carbon pathways associated with materials and construction processes. Studies employing lifecycle methodologies and input-output analytical techniques have quantified the sector’s carbon footprint, designating construction as a major emitter within the national economy [

9]. Case study research focusing on specific building components and lifecycle boundary definitions has demonstrated how design choices, material selections, and assessment methodologies influence embodied carbon estimates, emphasising the practical significance of carbon accounting for policy-relevant decarbonisation strategies [

10,

11].

As a result, by conducting EC calculations, Sri Lanka can align itself with global standards, rendering it more appealing for international collaborations, funding, and partnerships. Furthermore, understanding and accounting for EC can foster technological innovation and spur the development of local industries [

12]. This approach can encourage the adoption of cleaner and more efficient technologies, creating opportunities for local businesses to prosper by offering sustainable solutions. EC holds excellent value for Sri Lanka’s sustainability. There is also increasing interest among researchers in contributing to investigations on EC estimation across various entities, and many researchers are participating in these studies.

An example of this is the comprehensive evaluation conducted by Nawarathna et al. [

12], which analysed twenty different case studies of office buildings. Similarly, Kumanayake, Luo, and Paulusz [

13] and residential structures in Sri Lanka. Moreover, Kumari et al. [

14] highlight the importance of EC evaluation in high-rise buildings in Sri Lanka. Collectively, these studies underscore the need for more precise calculations and a reduction in assessment times to enhance acceptance within Sri Lanka.

1.3. Building Information Modelling and Life Cycle Assessment Integration: Digital Tools for Carbon Management

This concept of Building Information Modelling (BIM) integrated EC assessment has gained momentum primarily in developed nations [

15]. BIM technology is integrated with LCA methodologies to gauge buildings’ carbon emissions [

16]. This amalgamation offers enhanced accuracy and substantial time savings in the assessment process [

17]. BIM-LCA integration involves the streamlined amalgamation of data, real-time calculations, and interactive visualisation of carbon emissions. According to the findings by Xu et al. [

16], this integrated solution significantly automates the EC assessment process by transferring accurate material information to the LCA tool, resulting in a substantial improvement in efficiency for EC calculations. In Sri Lanka, the construction sector is increasingly recognising the benefits of BIM, such as enhanced project efficiency, decreased errors, and improved collaboration [

18]. Moreover, the number of educational programs focused on BIM technology is increasing, and the number of adept professionals is also rising [

19]. This burgeoning expertise indicates a progressing preparedness for a more holistic integration of BIM. Numerous projects in Sri Lanka have commenced the utilisation of BIM, showcasing successful outcomes and inspiring further exploration of its potential [

7]. The country is witnessing a shift in market demand, with clients and stakeholders recognising the value that BIM can bring to construction projects, thus fostering a favourable environment for its acceptance. Unfortunately, there is a notable scarcity of comprehensive and scholarly studies within the domain of EC assessment integrated with BIM in the context of Sri Lanka [

10]. This absence of extensive research is a matter of concern and urgency, demanding immediate attention. It is imperative to underscore the pressing need for the development and implementation of research initiatives that concentrate on integrating EC assessment within the Sri Lankan context using BIM.

1.4. The Sri Lankan Building Standard Rates: A Foundation for Localised Carbon Assessment

Within the Sri Lankan construction context, the Building Schedule of Rates (BSR), issued annually by the Building Department, represents an established institutional framework with significant potential for integration into embodied carbon assessment processes. The BSR serves as the longstanding standard work norm governing materials, equipment, and labour co119sts across construction projects, providing comprehensive specifications for diverse building elements through standardised item codes, descriptions, and measurement units (Building Schedule of Rates, 2023). Engineering professionals throughout Sri Lanka routinely consult the BSR for cost estimation purposes, rendering it a familiar and accessible reference framework across the construction industry.

The structural characteristics of the BSR present unique opportunities for integrating embodied carbon. Each BSR item comprises detailed material breakdowns that specify constituent materials and quantities, information generated during initial rate preparation processes. By systematically associating Embodied Carbon Factors (ECFs) with these material breakdowns, it becomes feasible to derive item-specific carbon intensity figures expressed in standardised units (e.g., kgCO2e per cubic meter or linear meter). This approach would establish a comprehensive, Sri Lanka-specific material database aligned with existing industry practices, potentially facilitating embodied carbon calculations without requiring substantial modifications to established professional practices.

The BSR-based approach to embodied carbon assessment offers several strategic advantages within the Sri Lankan context. First, it leverages an existing institutional infrastructure familiar to construction professionals, which may potentially reduce barriers to adoption. Second, it aligns carbon assessment with established cost estimation processes, enabling integrated consideration of economic and environmental factors. Third, it provides a standardised framework for carbon quantification across projects, supporting consistency and comparability essential for benchmarking and policy implementation. However, realising this potential requires systematic development of ECFs appropriate to Sri Lankan material production contexts, validation of database accuracy, and integration with digital modelling tools such as BIM platforms.

1.5. Research Gaps and the Imperative for BIM-Integrated Embodied Carbon Assessment in Sri Lanka

Although embodied carbon assessment is important and more people worldwide are utilising BIM-LCA integration methods, significant gaps remain in research and implementation within the Sri Lankan construction industry. A primary limitation recognised in Sri Lankan embodied carbon research is the lack of a national standard for carbon measurement, along with restricted access to localised, material-specific data. This deficiency hinders consistency in assessments and cross-project comparability. This data and governance gap is a major bottleneck for efforts to measure and reduce embodied carbon on a large scale. It slows down both research and real-world use [

13].

The lack of capacity, training, and institutional support makes it even more challenging to utilise LCA and embodied carbon methods effectively in Sri Lanka’s construction industry. Research has identified skill deficiencies and organisational preparedness issues that hinder the extensive implementation of carbon assessment methodologies in construction design and decision-making processes [

20,

21]. These limitations are especially evident due to the sector’s growth trajectory and diversification, which simultaneously increases the demand for comprehensive carbon accounting while exerting pressure on companies to innovate and compete amid resource constraints (Weerakoon et al., 2023).

Furthermore, there is a clear lack of thorough academic research on BIM-integrated embodied carbon assessment in Sri Lanka [

10]. International literature demonstrates the technical feasibility and considerable advantages of integrating BIM-LCA. Concurrently, Sri Lankan research has highlighted the sector’s economic importance and initiated efforts in quantifying embodied carbon. However, the systematic amalgamation of BIM methodologies with localised carbon assessment frameworks, especially by utilising established institutional infrastructure like the BSR, has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

This research gap is troubling because the sector has a big impact on the economy and the environment, BIM-LCA has been shown to improve the accuracy and efficiency of assessments, and Sri Lanka has made promises to be more environmentally friendly under international frameworks. Accordingly, this paper aims to bridge the existing research gap in EC calculation by utilising BIM in the specific context of Sri Lanka. By developing a comprehensive framework, it aims to contribute to the field by serving as a foundation for future studies. The purpose of this paper is to pave the way for further research and exploration in this area by taking this critical step forward. Moreover, this research addresses this gap through the following objectives in the next section.

1.6. Research Objectives

Primary Objective: Develop a pragmatic BIM-integrated framework for EC assessment tailored to Sri Lankan construction industry characteristics, utilising indigenous data sources and accessible software tools.

Specific Objectives:

Critically analyse existing BIM-LCA integration methodologies through a systematic literature review, identifying key parameters, tools, databases, and implementation approaches.

Evaluate Sri Lanka’s BSR document as a potential indigenous data source for EC calculations.

Design a comprehensive framework integrating BSR data with BIM parametric modelling approaches using Revit and Dynamo.

Validate framework feasibility and applicability through expert consultation with Sri Lankan construction industry professionals.

Identify implementation barriers and propose strategies for overcoming challenges specific to developing country contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

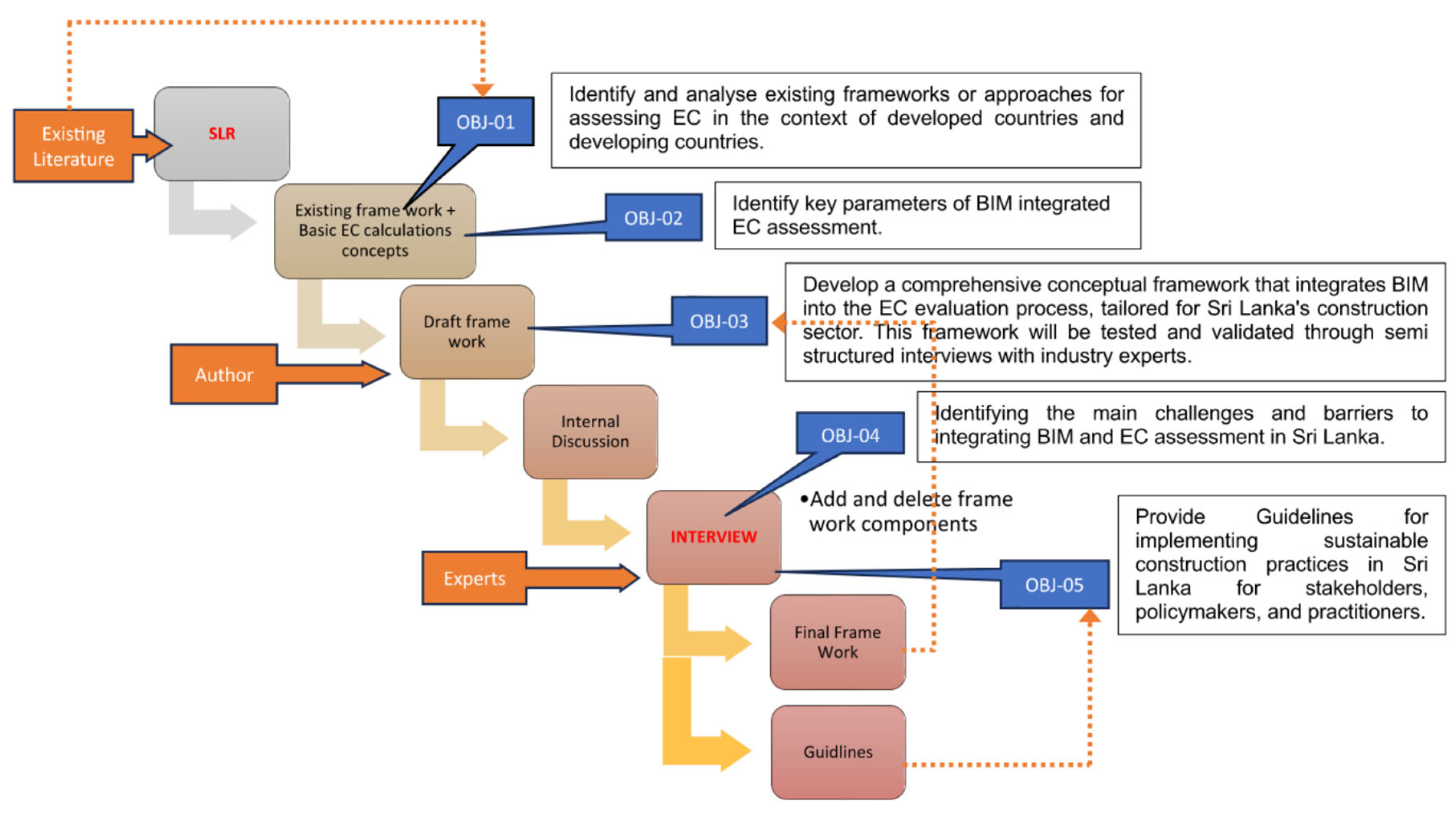

This study employed the systematic literature review (SLR) methodology in conjunction with an expert interview to validate the proposed framework [

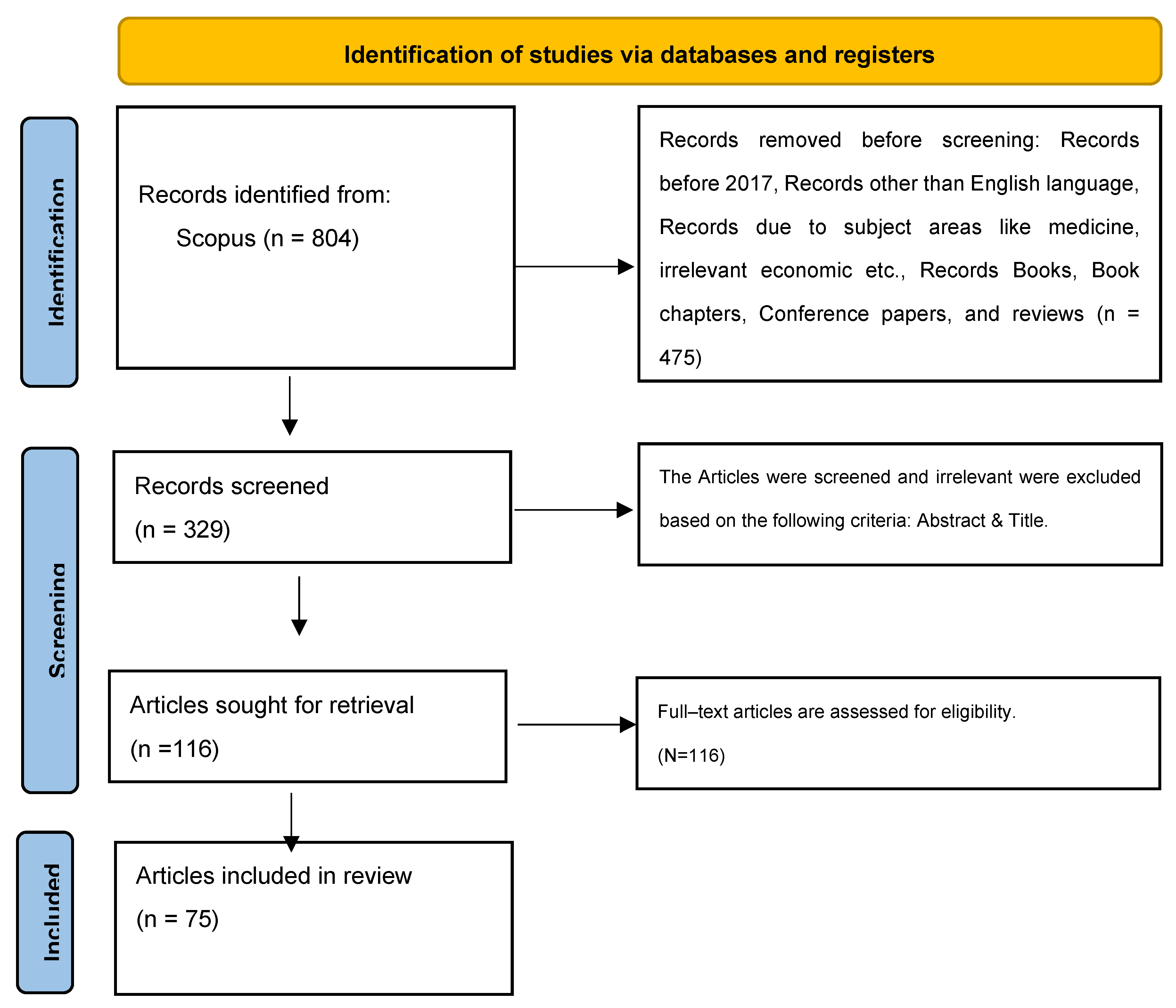

22]. A Complete overview of the research methodology is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.1. Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

A SLR has been employed as our primary methodology, adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework [

23] for comprehensive reporting. This approach was chosen due to its wide acceptance in the built environment field, ensuring objectivity, precision, and comprehensiveness [

24]. Given the study’s objective to formulate a conceptual framework for integrating BIM into EC assessment within the Sri Lankan context, SLR proved suitable for exploring the latest BIM integration technologies [

25]. Following a four-step process adapted from Rabiser, Grünbacher, and Dhungana [

22], the SLR utilised Scopus, known for its extensive archive and reputation as the largest global repository of peer-reviewed publications, covering business, management, construction management, and engineering literature [

26].

2.1.1. Search Strategy

The identification of relevant articles began with the selection of an appropriate database and keywords, as outlined by Deng and Smyth [

27]. Utilising specific keywords, the study focused on terms such as BIM, “Embodied carbon,” EC, “Carbon Assessment,” LCA, “Life cycle assessment,” “Calculation methodology,” “Embodied carbon in building services,” “Material selection,” “Embodied carbon emission,” EPD, and “Environmental product declaration.” These terms were combined using “AND,” “OR,” and “AND NOT” operators. After iterative attempts and experiments, the final search term for Scopus articles emerged as: “( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( BIM ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Embodied carbon*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( EC ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Carbon assessment*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( LCA ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Life cycle assessment*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Calculation methodology”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Embodied carbon in building services”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Material selection”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Embodied carbon emission*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“EPD*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Environmental product declaration”) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Operational carbon”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“OC”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Life cycle cost”) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2016 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “ENGI”) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “ENVI”) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “MULT”) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , “ar”) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , “English”) )”

2.1.2. Selection Criteria

To conduct a thorough literature review on EC assessment and BIM within the engineering domain, this study meticulously followed the PRISMA Statement [

28]. The search scope encompassed engineering, environmental science, and multidisciplinary fields, with a focus on articles published exclusively in English. Articles from the period between 2017 and 2025 were considered, deliberately excluding those predating 2017 to capture recent advancements. Despite adopting a broad international perspective, the study retrieved a relatively limited number of articles from developing nations. The exclusion process during the preliminary search phase systematically removed 475 research articles due to factors such as non-English records, irrelevant subject areas, and non-peer-reviewed formats like books, book chapters, conference papers, and reviews, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The emphasis on peer-reviewed papers aligns with the need for rigour and accuracy, as highlighted by Thelwall [

29], ensuring the inclusion of reliable information in the study. Ultimately, 329 records were identified for the subsequent stages of the review.

2.1.3. Quality Assessment

To ensure the review’s integrity, a meticulous examination was conducted to identify potential duplications. Abstracts underwent a comprehensive scrutiny, refining articles for academic calibre and relevance. A subsequent phase involved a detailed screening of each scholarly article. Articles focusing on cost aspects, energy, thermal analysis, building facades, and demolition waste were excluded from the study. In this screening, an additional 253 articles were removed, comprising 213 from title and abstract screening and 40 from full-text screening, as they did not contribute substantively to the study’s objectives. Following the rigorous application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 75 articles were selected, meeting the standards set for the review process.

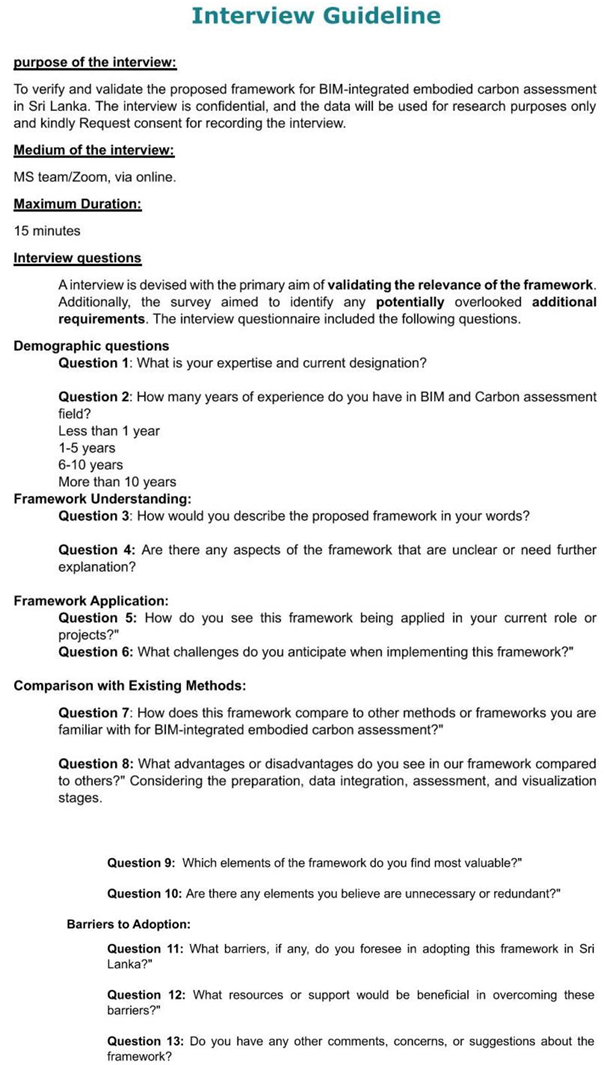

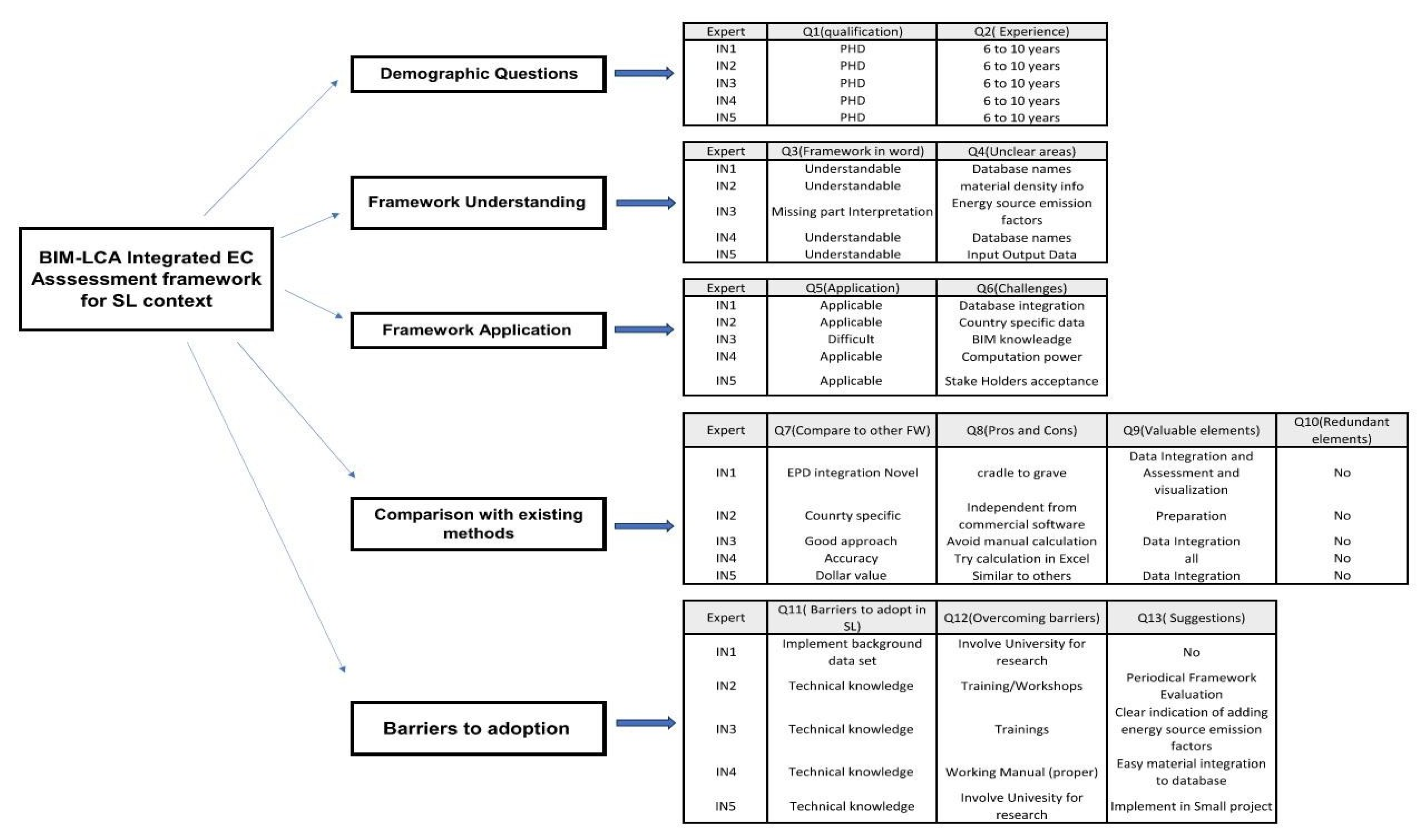

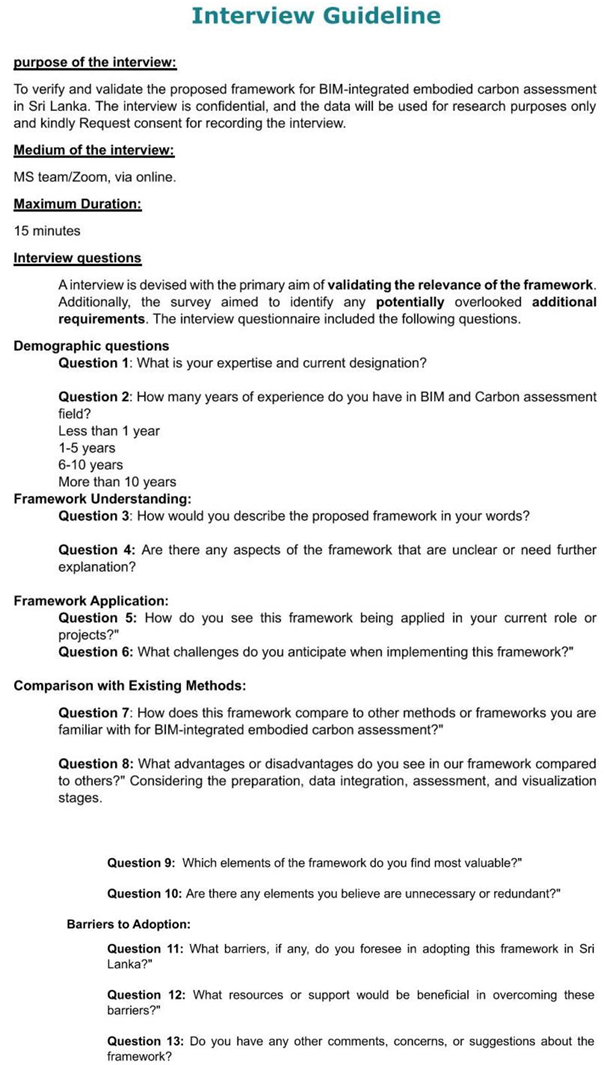

2.2. Expert interview

Drawing insights from the SLR guided by PRISMA guidelines, a conceptual framework tailored to the unique context of SL was formulated. To validate its relevance and comprehensiveness, an expert survey was conducted following Rabiser, Grünbacher, and Dhungana’s [

22] approach. Five esteemed Sri Lankan experts, each holding a doctoral degree, brought over a decade of invaluable experience in BIM-LCA to the interviews. Their extensive expertise, marked by advanced academic qualifications and years of professional practice, ensured a nuanced and comprehensive evaluation of the BIM-integrated carbon assessment framework. The interview questionnaire covered demographics, understanding of the framework, application comparison to existing methods, and barriers to adoption. Expert suggestions prompted modifications, refining the framework to meet specific requirements and addressing potential misunderstandings that arose during the interview process.

Figure 2.

Statement under PRISMA Framework.

Figure 2.

Statement under PRISMA Framework.

2.3. Data Analysis

The analysis unfolds in three stages. Firstly, SLR findings are scrutinised, employing VOSviewer for literature clustering [

30] which identifies primary areas within the BIM-LCA integrated assessment process. The Co-occurrence analysis using VOSviewer reveals crucial parameters [

31]. In the second step, a co-occurrence analysis of terms is conducted, extracting key variables for correlation coefficient calculation [

23] using the ATAtab online tool [

32]. Positive and negative correlations signify relationships, with “P” values determining significance. Preparation of Scatter plot charts based on these variables further enhances understanding [

33], contributing to the BIM-integrated LCA framework for EC assessment tailored for the Sri Lankan context. In the subsequent phase, expert interview transcripts undergo manual coding to identify themes [

34], discussing views and framework elements. The final analysis stage comprehensively evaluates SLR and interview data, using overlapping scatter plot graphs to synthesise insights [

33] and draw conclusive findings from the integrated examination of both sources.

3. Results

3.1. General Features

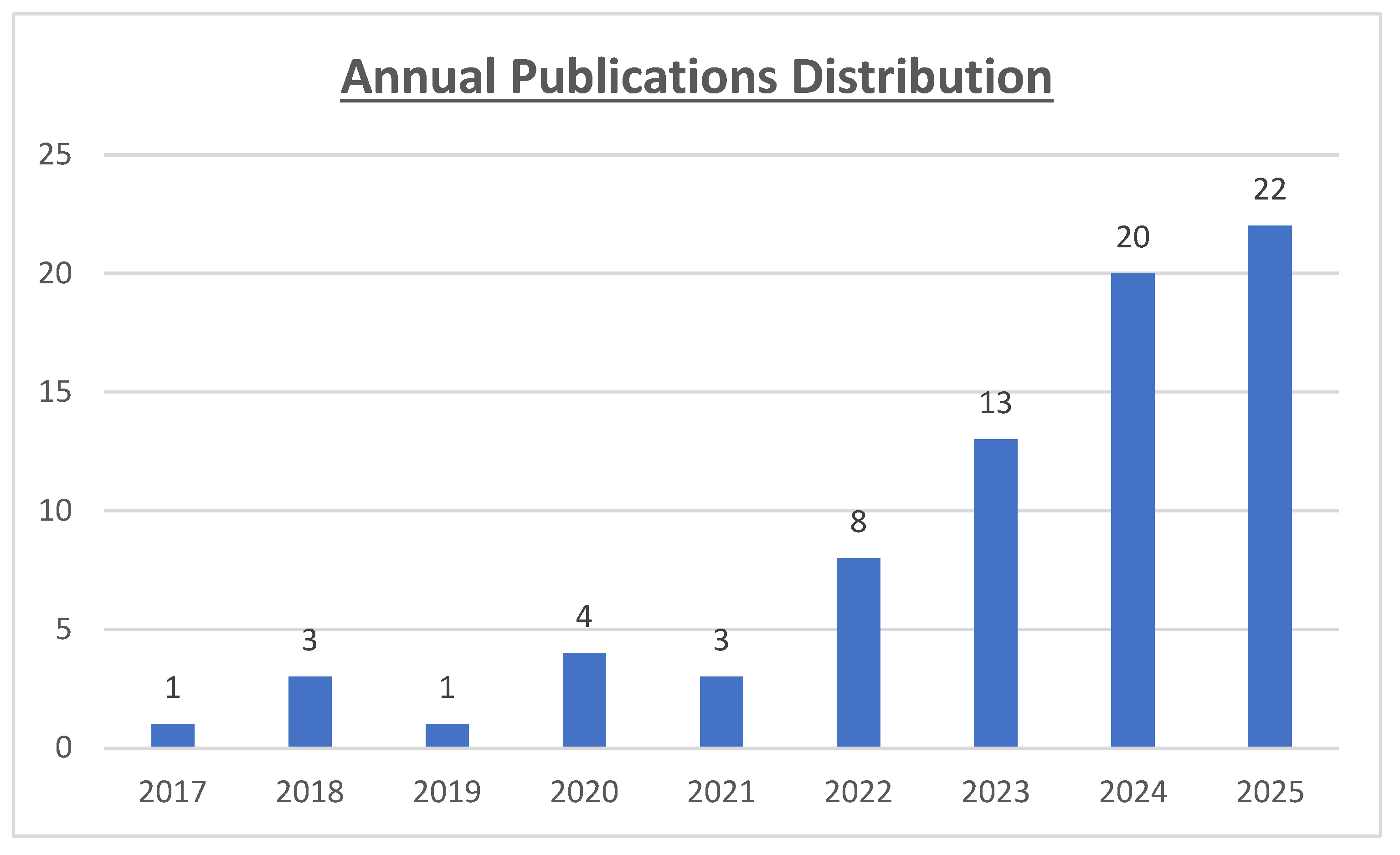

A total of 22 papers appeared in the year 2025 from 75 publications generated by the SLR (see

Figure 3). The number of papers in 2025 constitutes 29.3% of the total number of papers since 2017. BIM-LCA has been increasingly integrated into EC evaluations based on the data. In 2042 and 2025, 20 and 22 papers were published, respectively, indicating an increasing interest in the field.

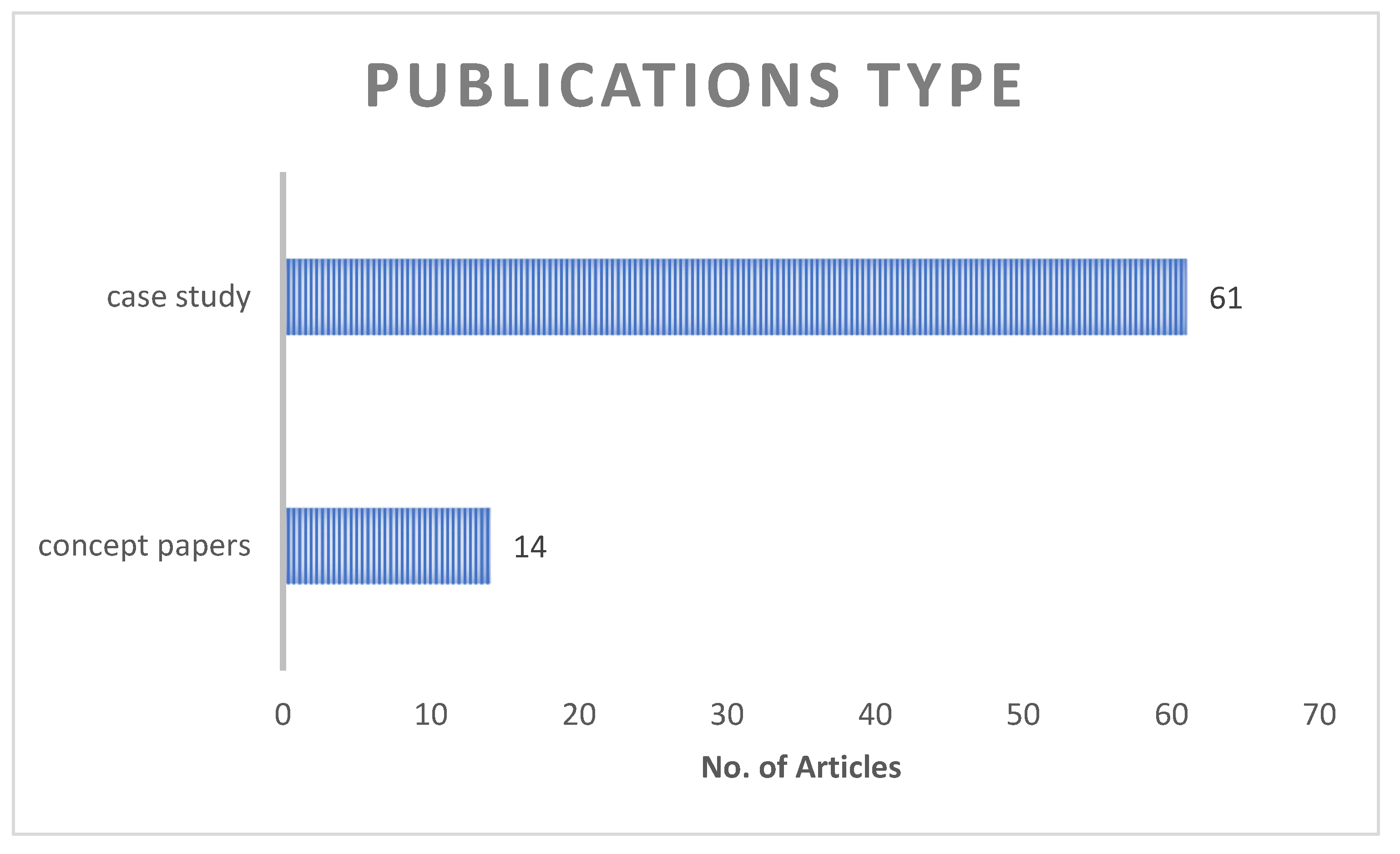

Out of the 75 examined publications, 81.3% identified as case study-based studies and only 18.67% (14 papers) were identified as concept papers (

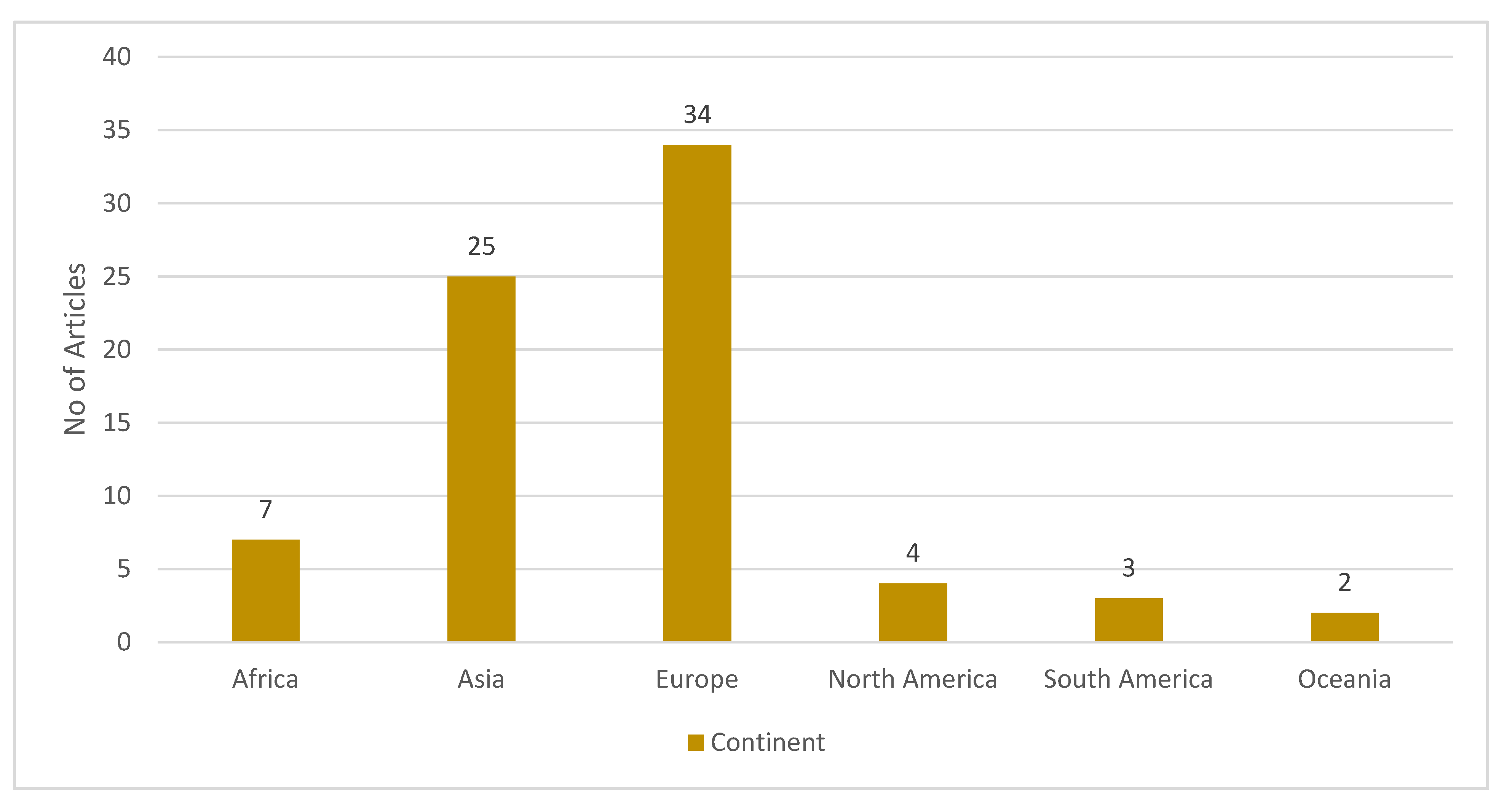

Figure 4). Case study Publications are mainly distributed throughout the five continents: Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America (

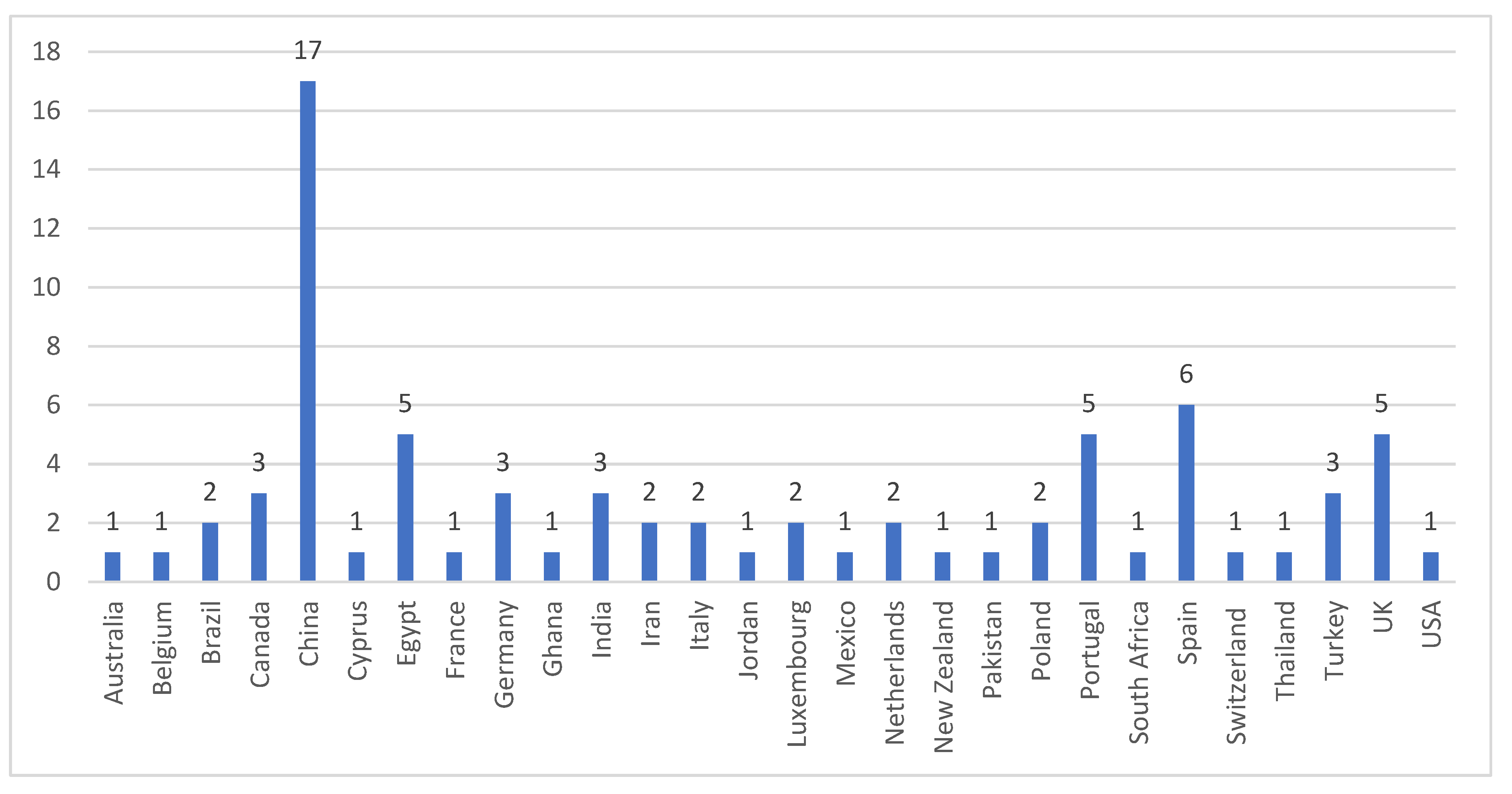

Figure 5). China, India, and Iran are among the major contributors to the Asian continent. China has undertaken the highest number of research endeavours (

Figure 6).

3.2. BIM-LCA Base Embodied Carbon Assessment Key Parameters

Utilising the VOSviewer clustering method in bibliometric research enables the analysis and visualisation of scientific publications. This approach effectively delineates key ideas within short-listed papers [

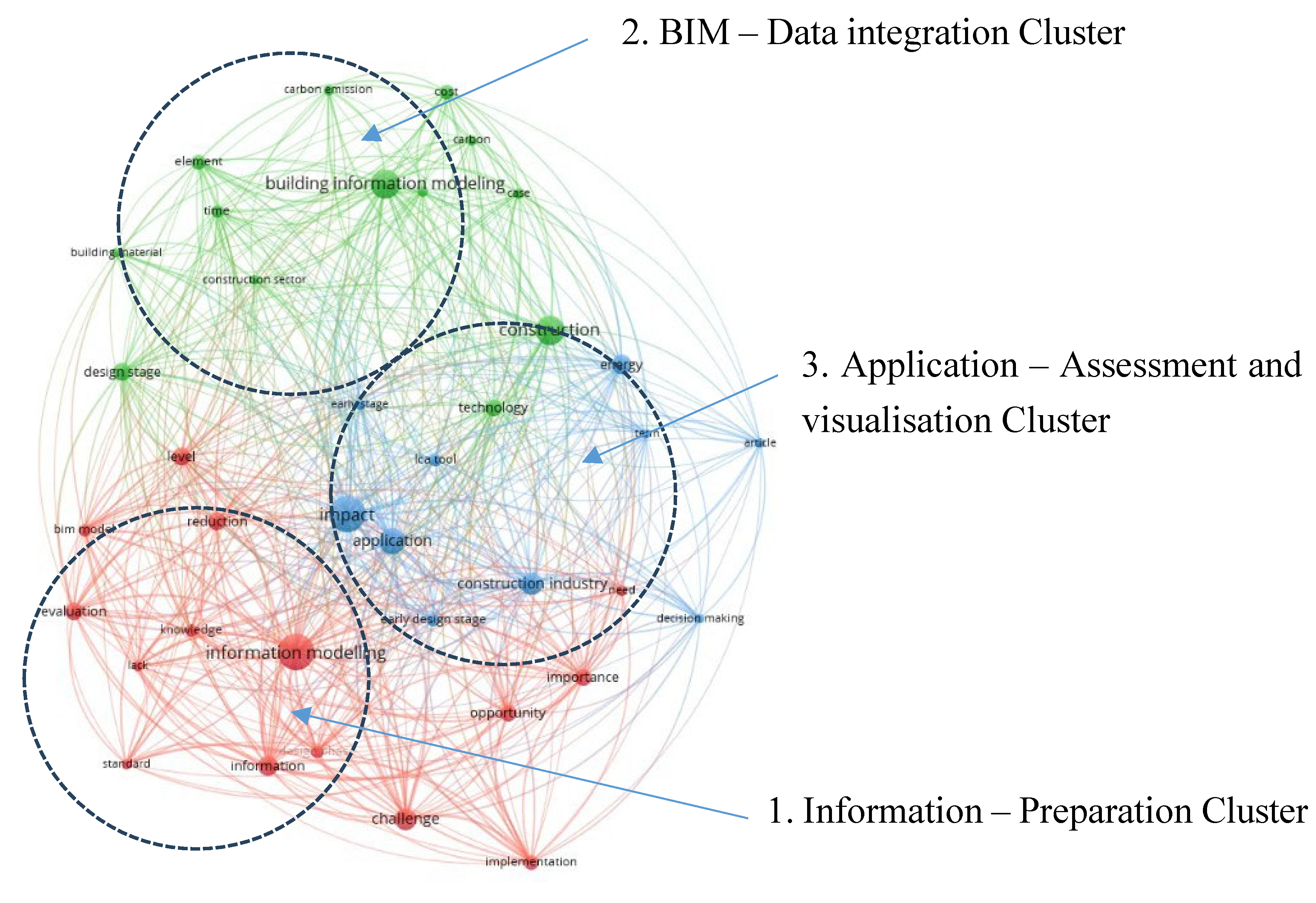

35]. In the identified literature clusters, three prominent groups emerge: the BIM cluster, the application cluster, and the information cluster (

Figure 7). Terms co-occurrence and Content analysis of these clusters reveal their significant contributions to BIM-LCA-based EC assessment, encompassing data preparation, integration, assessment, and visualisation. The information cluster primarily focuses on terms related to databases, EPDs, and ECFs. The BIM cluster revolves around terms associated with feeding data into BIM models using auxiliary tools and standard documents. Meanwhile, the application cluster emphasises key terms related to LCA tools, scripting languages, ultimately leading to the assessment and visualisation aspects of the research.

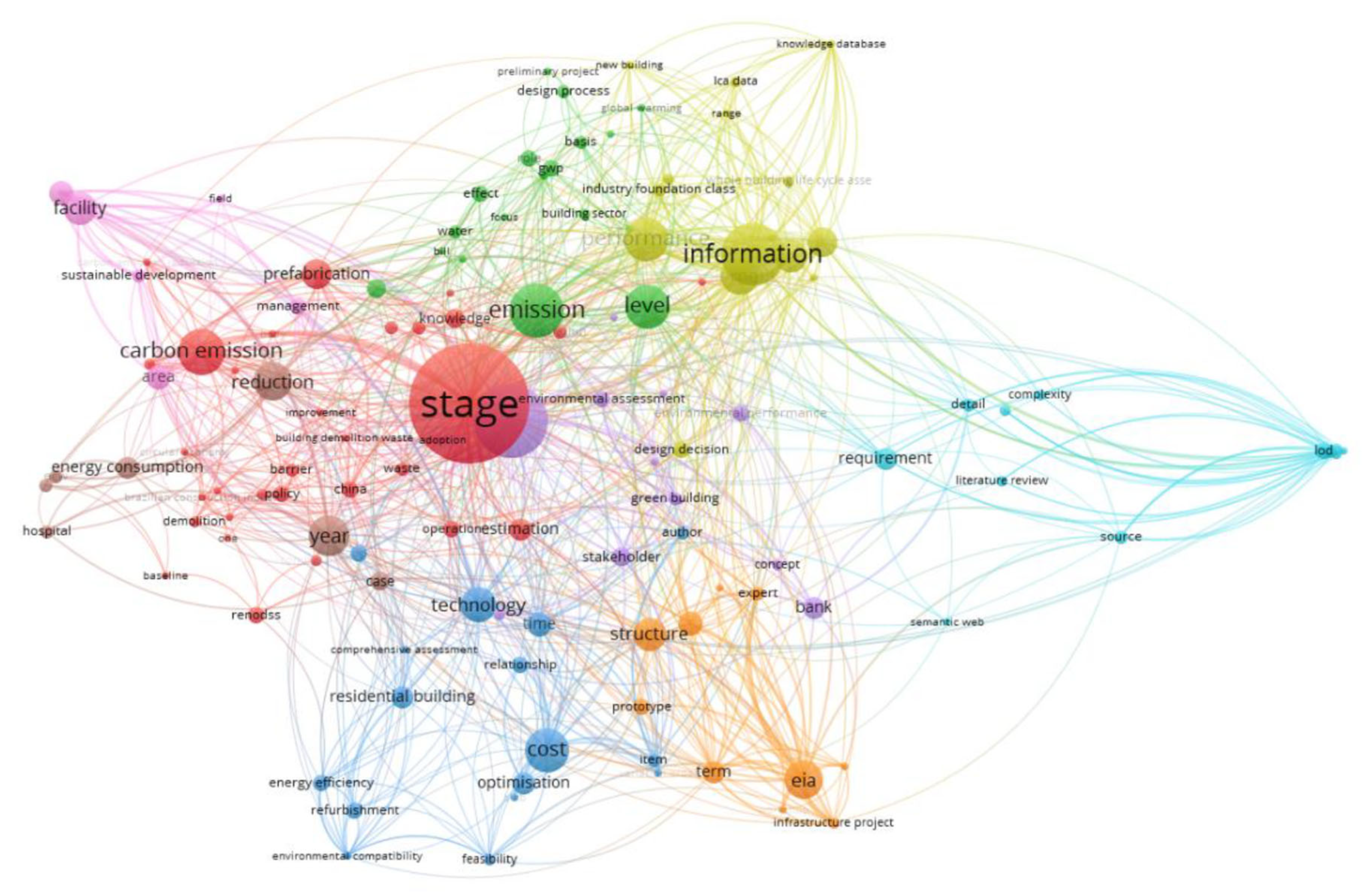

Through the analysis of text data from the Scopus database file, a term co-occurrence map was generated using the VOSviewer. The number of occurrences represents the term’s importance. Those are helping to identify key parameters. Extracted from titles and abstracts, these terms are weighted based on word frequency, and a relevance score is calculated to select the most significant terms (

Figure 8). The recurring terms in the extracted papers are considered key parameters for BIM-LCA integrated EC assessments, and their contributions are detailed in the

Table 1, with their meaningful conversions listed below as P1 to P8, as the following:

P1-BIM Model Geometry,

P2-Material Information,

P3-LCA Data,

P4-Transportation Data,

P5-Building Use and End-of-Life Considerations,

P6-Data Interoperability,

P7-Data Accuracy and Precision,

P8-Energy Performance Data.

3.3. BIM Tools

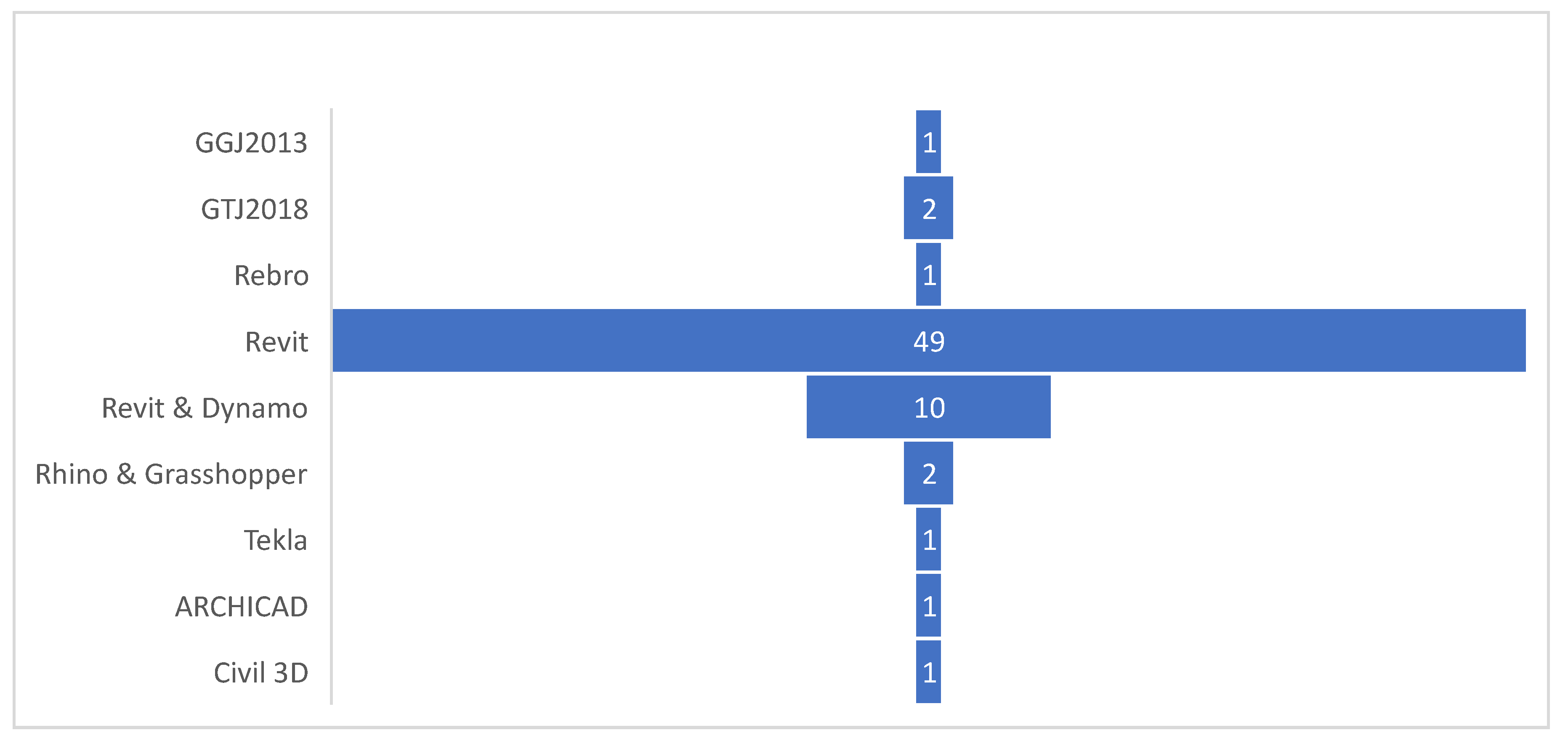

In the 75 articles, Revit was used as a BIM tool in 72% of the cases. On the other hand, Chinese researchers have used modelling software such as GTJ2018 and GGJ2013. In particular, two researchers chose Rhino for modelling. Many research papers have used the Dynamo plugin (15%) in conjunction with Revit (

Figure 9).

There exist BIM tools beyond Autodesk products, specifically GGJ2013, GTJ2018, and Rhino. Their distribution is represented in the selected research papers.

3.4. LCA Tools

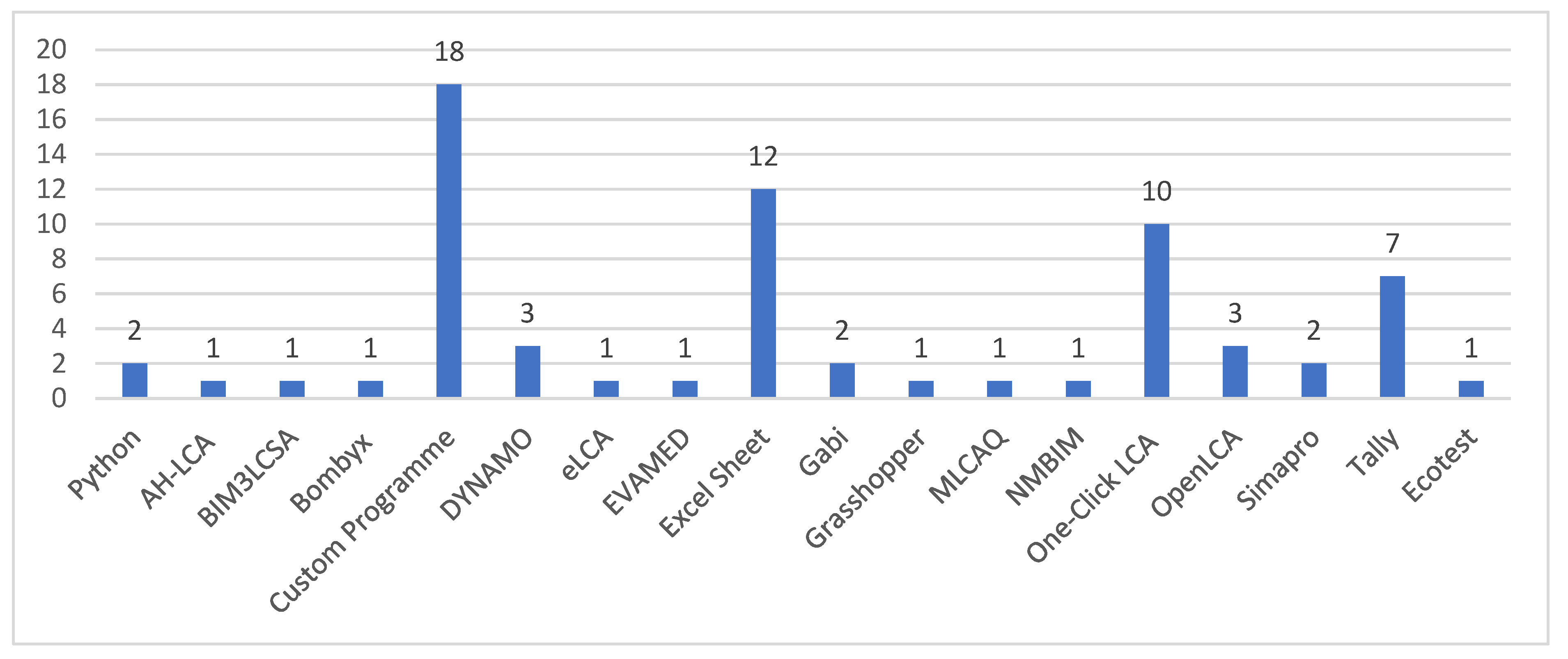

Several LCA tools have been employed in diverse research endeavours. The use of Excel sheets as the primary LCA tool stands out as a widely adopted approach, featuring in 12 research articles among the shortlisted papers. Tally and OneClickLca follow closely as the second most popular tools, each contributing of 7 and 10 of research articles (

Figure 10). All other identified tools are outlined in the figure below, with their utilisation being minimal across the shortlisted research articles.

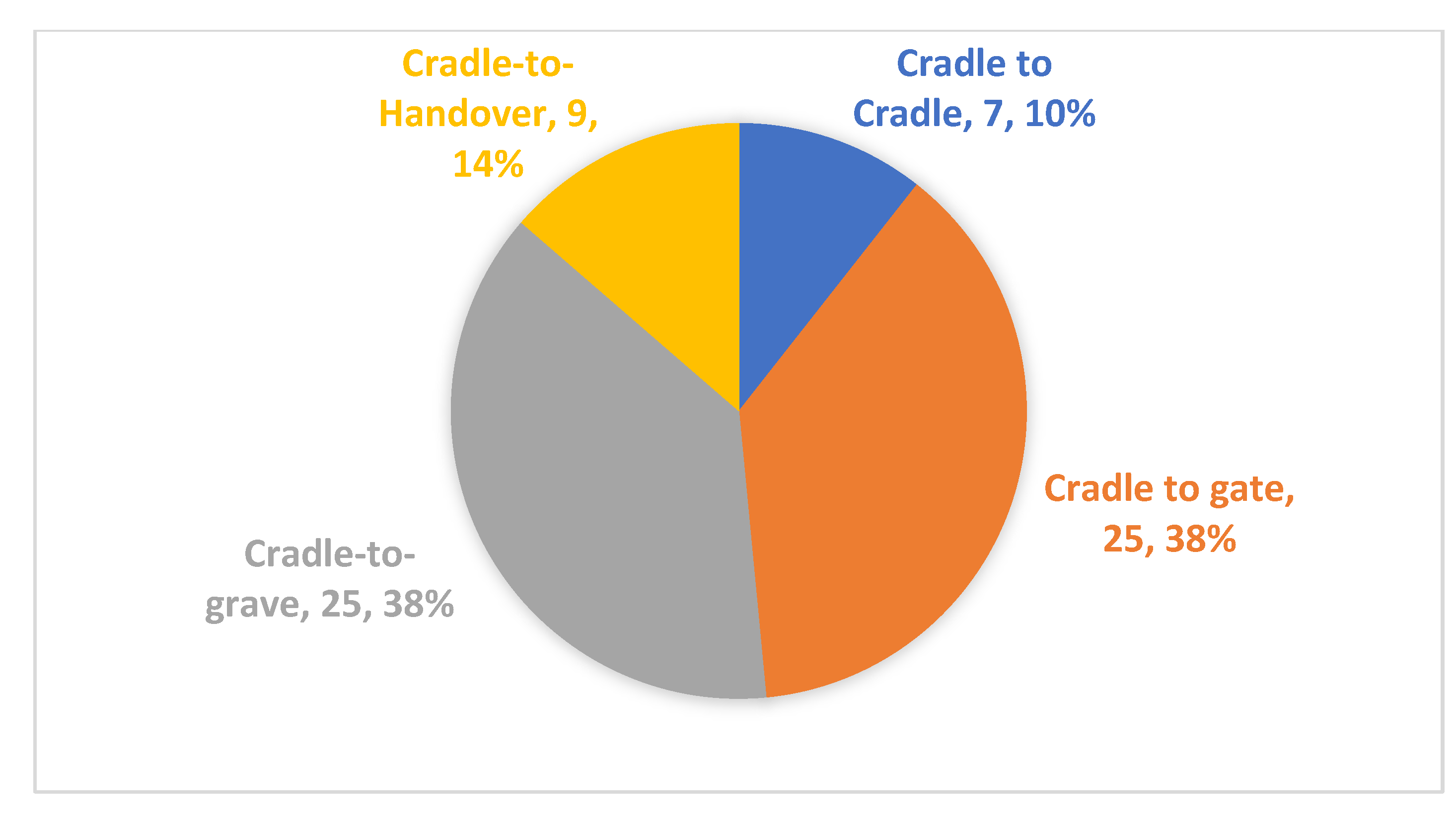

3.5. System Boundaries and Life Cycle Stages

Within the EC assessment process, there are four fundamental system boundaries. A1- A3 are cradle to gate boundaries, A1-A5 are cradle to handover boundaries, A1-A5, B1- B5, C1-C4 are cradle to grave boundaries and A1-A5, B1-B5, C1-C4, and D are cradle to cradle boundaries. Among the chosen research studies, the most commonly employed system boundaries are cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave (25.4% in each case), as illustrated in

Figure 11.

3.6. LCA Database

Figure 12 portrays the quantity of scholarly articles that are in opposition to the specific database employed by each research. Ecoinvent is widely acknowledged as the most important database among researchers (15.4%). Following closely behind is the EPD and Local datasets, which is utilised by a significant proportion of research endeavours (13.84%). OneClickLCA also enjoys considerable popularity (12.3%). A small number of studies employ multiple data sources, encompassing BEDEC, ICE, and ÖKOBAUDAT.

3.7. Correlations Between Key Variables of the Initial Framework

The correlation coefficient serves as a statistical metric to evaluate the relationship between variables by quantifying the strength and direction of their association [

109]. Ranging from -1 to +1, a coefficient of 0 indicates no association, while a closer proximity to -1 or +1 signifies a stronger relationship. Commonly employed correlation coefficients include the Pearson product-moment correlation for normally distributed data and the Spearman rank correlation for non-normally distributed or ordinal data [

109]. Statistical significance of the correlation can be assessed through hypothesis tests and confidence intervals [

110].

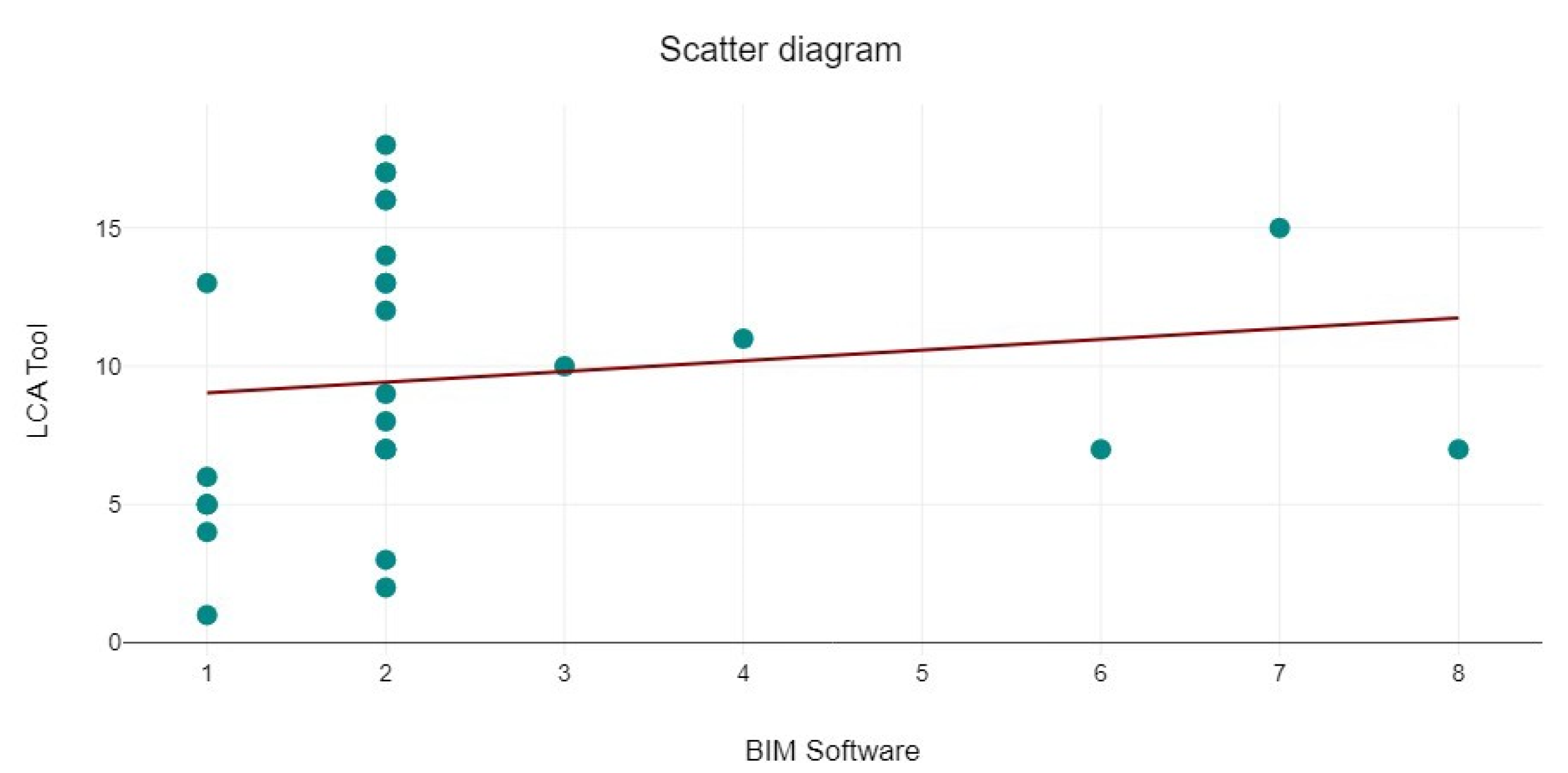

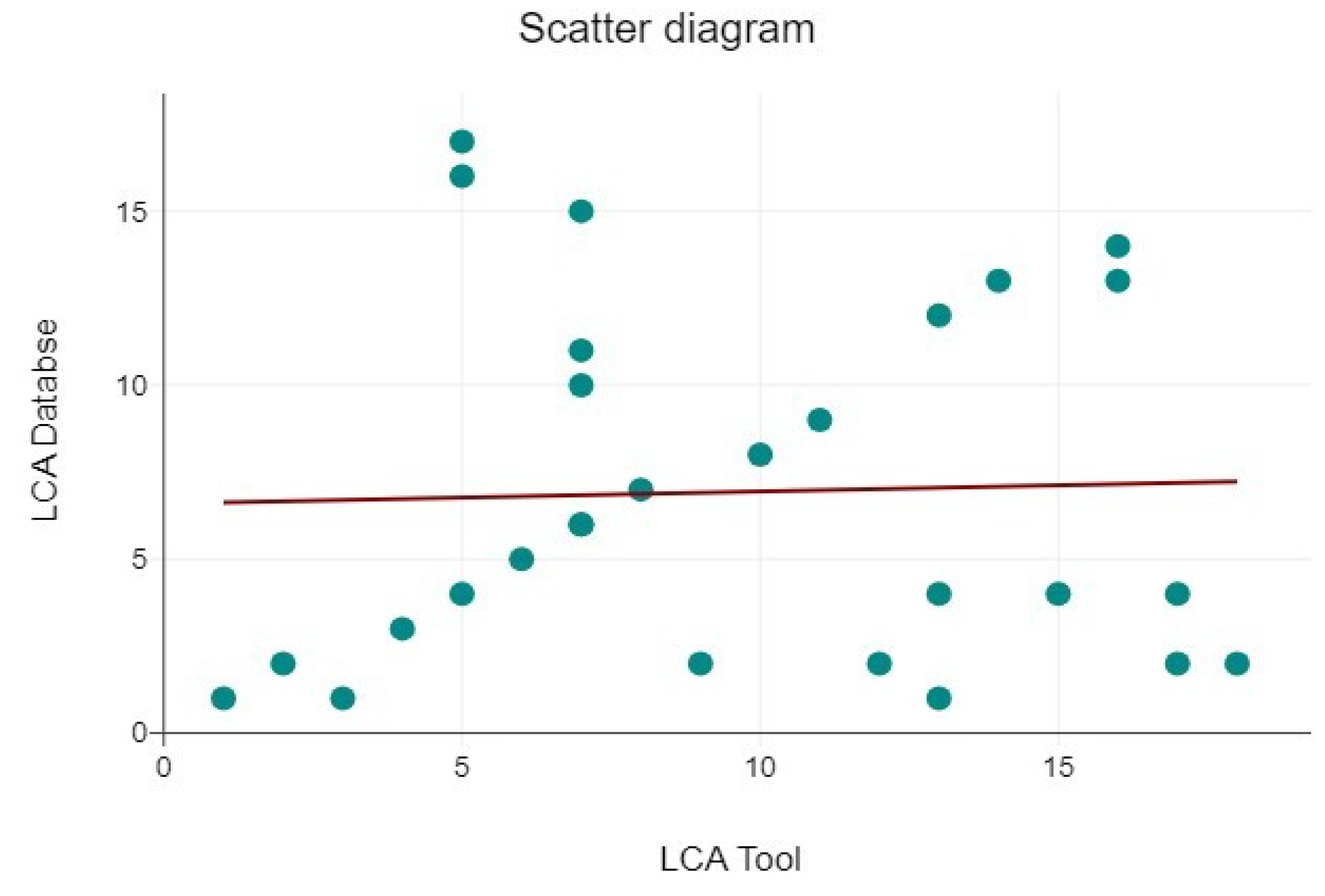

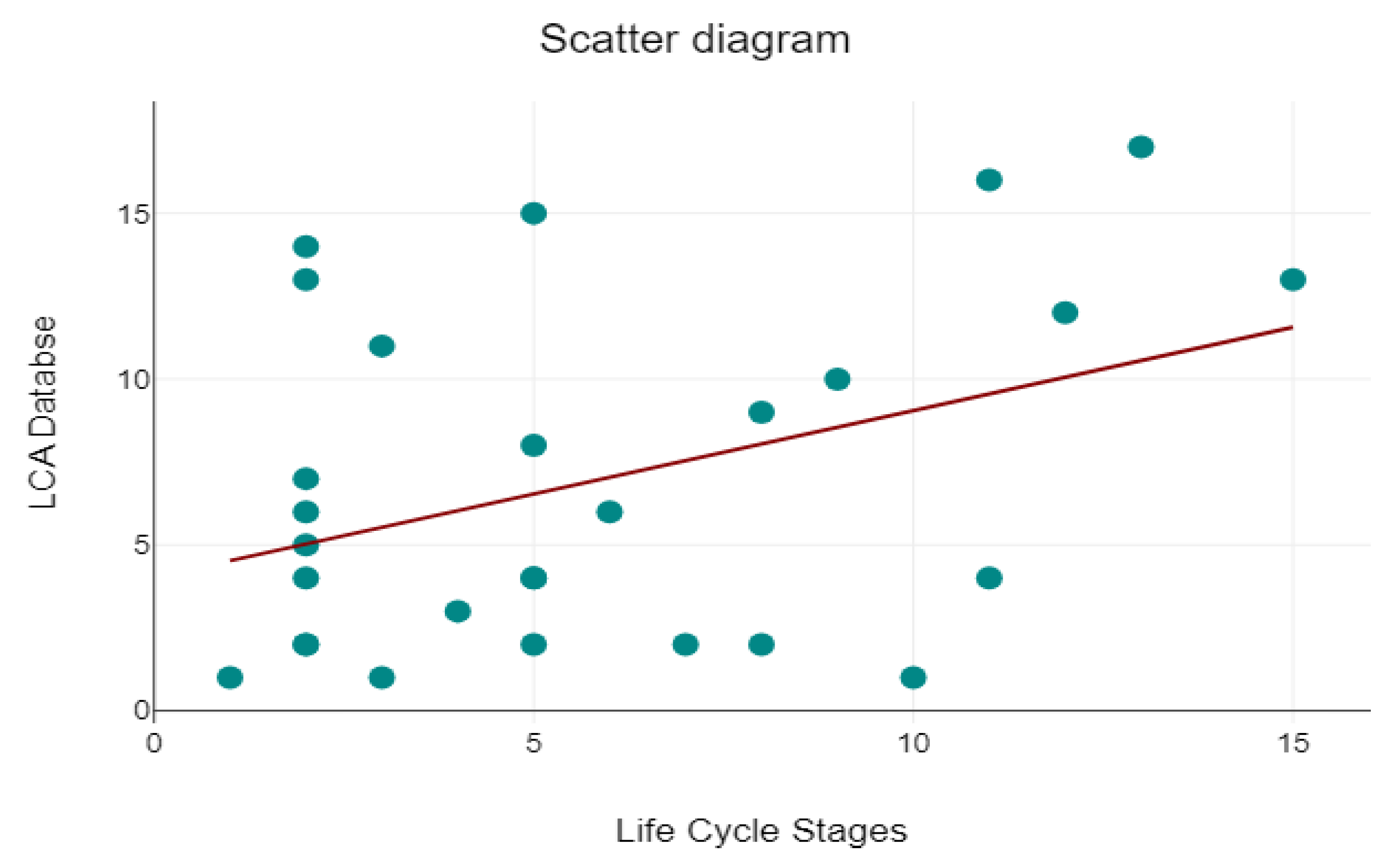

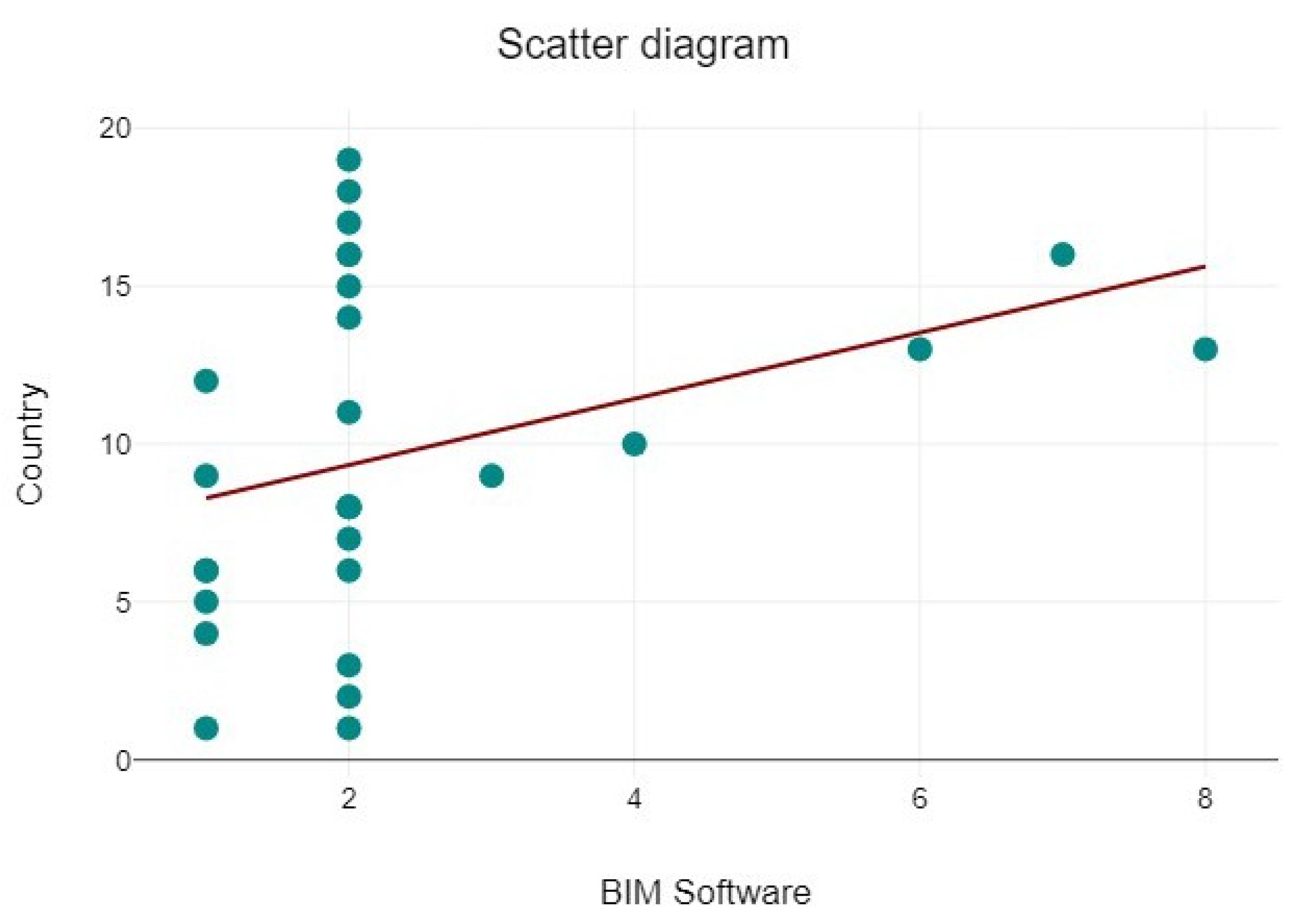

A Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the correlation between the selected variables, which serve as key variables in the framework, assuming the monotonic nature of the relationship and the ordinal distribution of the non-normally distributed data [

109]. To evaluate the correlation between BIM Software and LCA Tool, a correlation analysis was performed, revealing a moderate, positive correlation (

Figure 13) with a coefficient of r = 0.39. Likewise, a negligible, positive correlation (

Figure 14) with r = 0.06 was observed between the LCA Tool and the LCA Database, indicating a minimal association between these variables in the studied sample and regarding Life Cycle Stages and LCA Database, a low, positive correlation (

Figure 15) emerged with a coefficient of r = 0.3, suggesting a modest relationship between these two variables within the sample. In the examination of BIM Software and Country, a moderate, positive correlation (

Figure 16) of r = 0.43 was identified, indicating a moderate positive relationship between BIM Software and Country in the analysed sample.

To evaluate the correlation between variable pairs, p-values were used to test the hypothesis that the observed correlations significantly differ from zero in the population, using a standard significance level of 0.05. BIM Software and LCA Tool showed a statistically significant correlation with r = 0.39 and p = 0.04. Conversely, the correlation between LCA Tool and LCA Database (r = 0.06, p = 0.745) was not found to be statistically significant, suggesting a likely chance association. Similarly, the correlation between Life Cycle Stages and LCA Database (r = 0.3, p = 0.125) was not deemed statistically significant. The correlation coefficient between BIM Software and Country, however, was 0.43, with a p-value of 0.022, indicating a significant relationship. In summary, these findings provide insights into the statistical significance of the observed correlations, guiding the understanding of the relationships within the analysed sample.

Considering the R2 values, it is observed that the BIM software and LCA tool share 15% of the variables, while the BIM software and country share 18%. This implies that the remaining percentages, 15% and 18%, respectively, are governed by unknown factors.

In summary, the interdependency of these variables appears to be influenced by a multitude of unknown factors. Therefore, the framework must adapt and respond to the situation, considering the comprehensive aspects of the intended purpose.

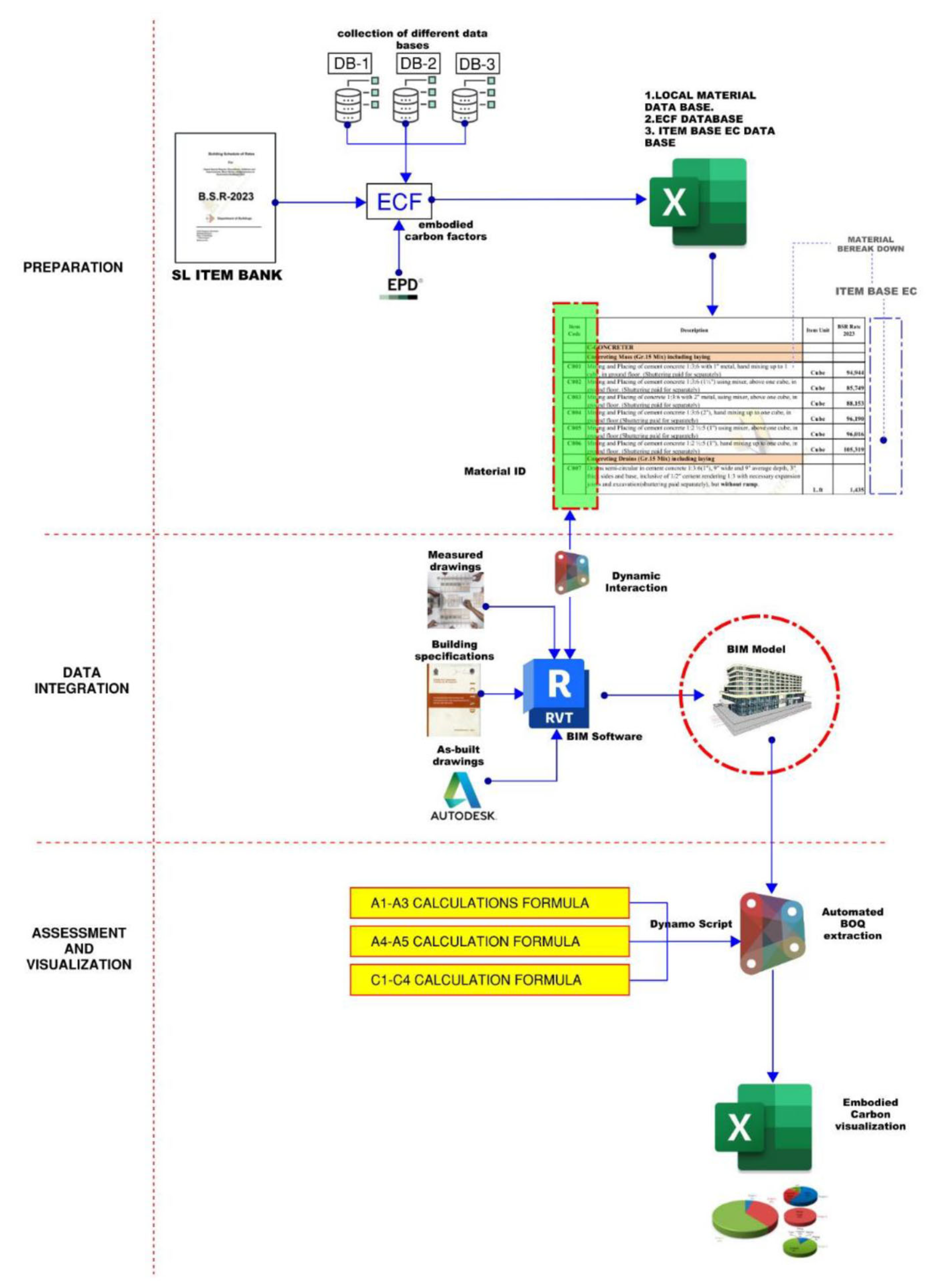

Based on the initial insights garnered from the SLR and statistical analysis,

Figure 17 elucidates the primary framework crafted for the assessment of EC through the integration of BIM and LCA. This framework delineates three key stages: preparation, data integration, and assessment and visualisation. A detailed exploration of these stages and processes will be undertaken in the next section.

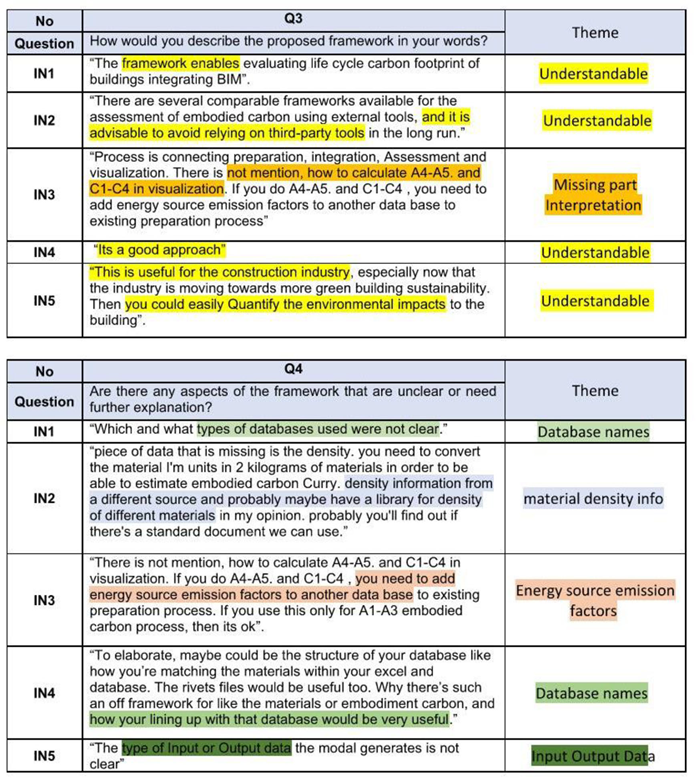

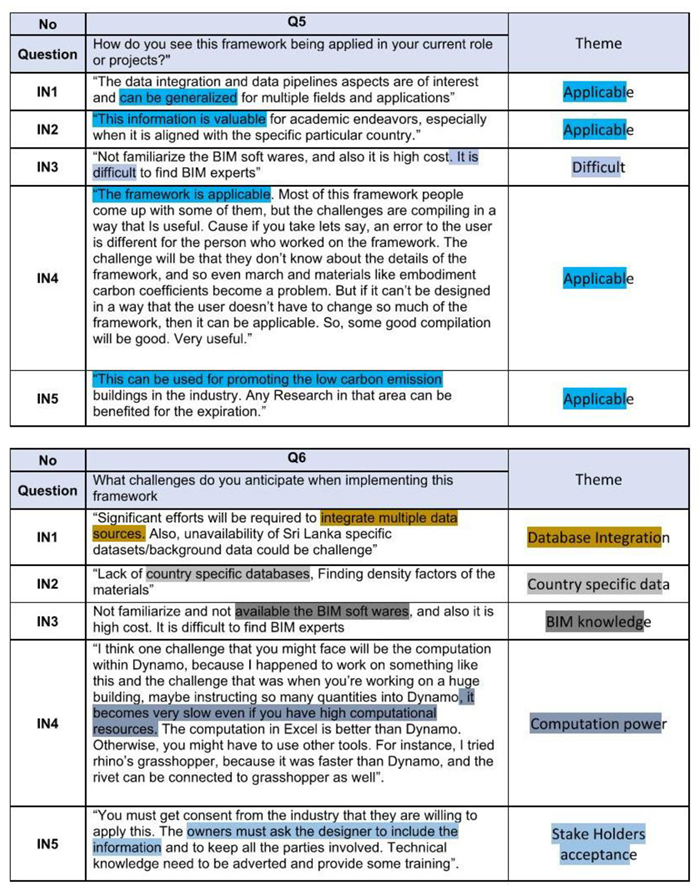

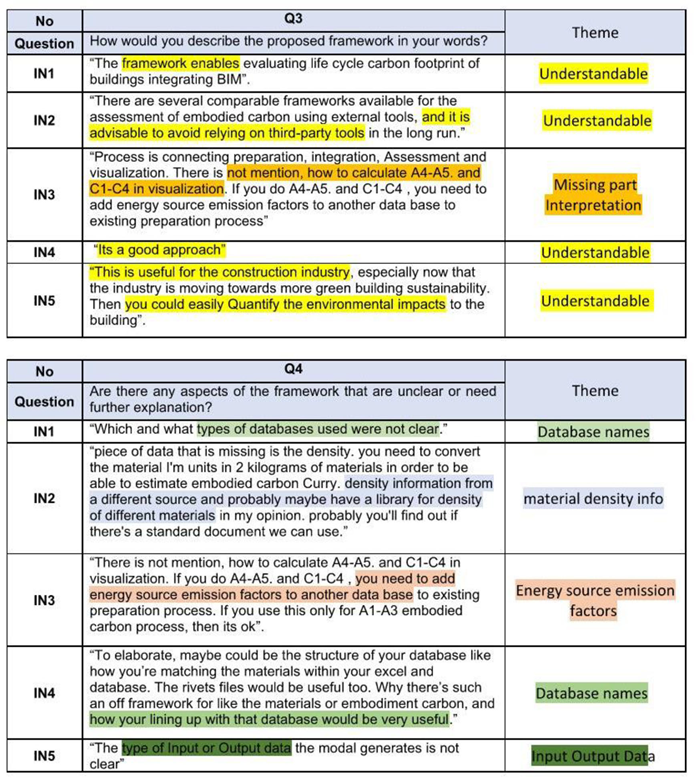

3.7. Expert Interview

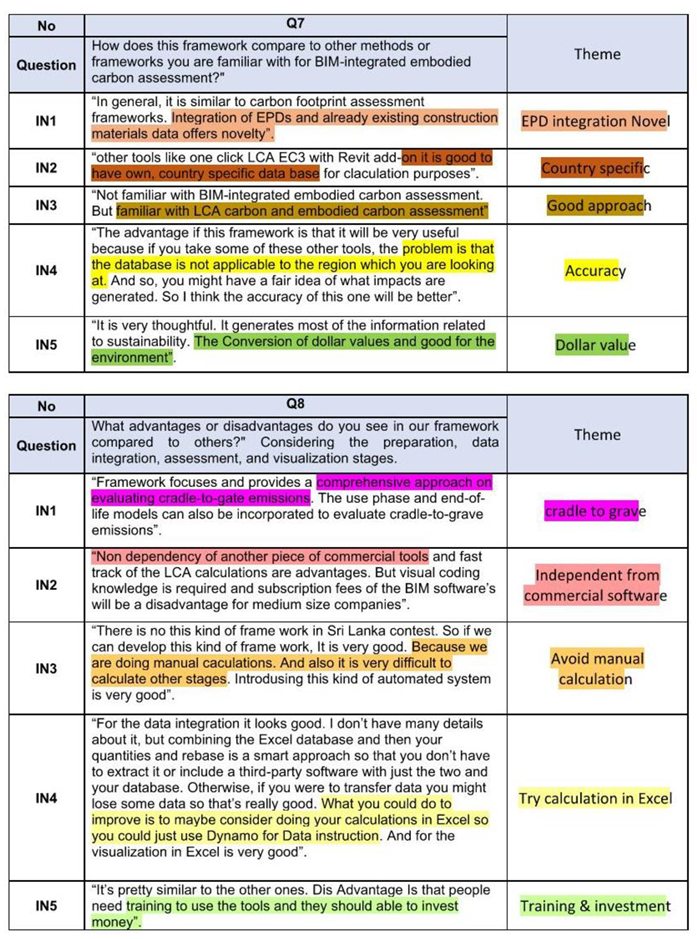

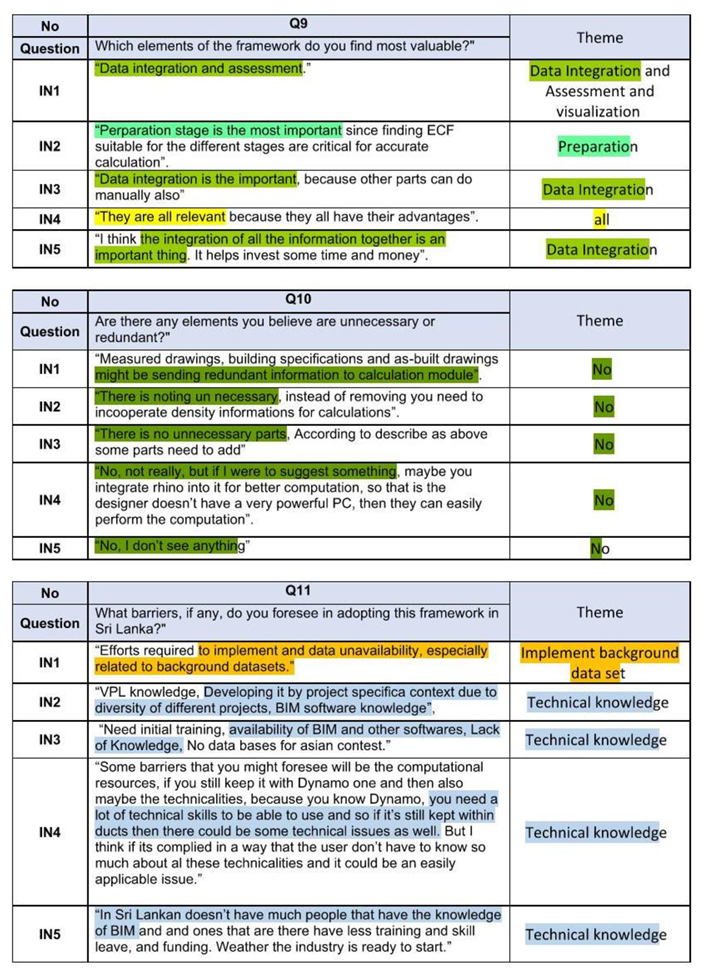

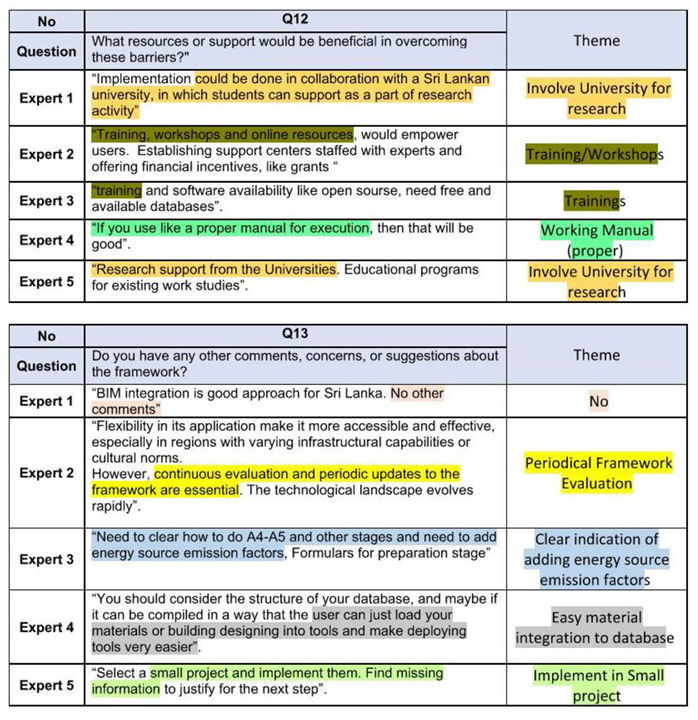

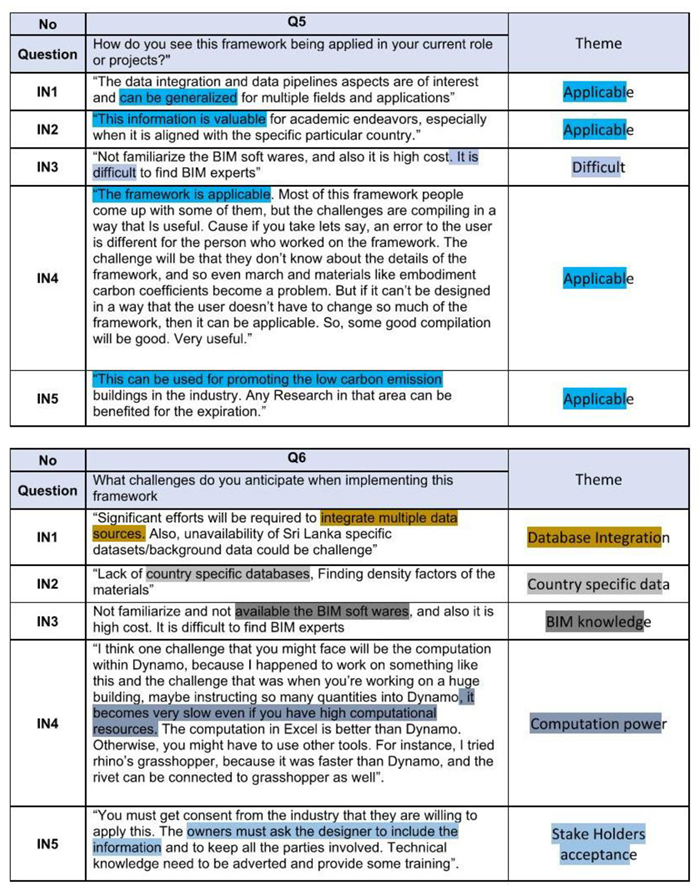

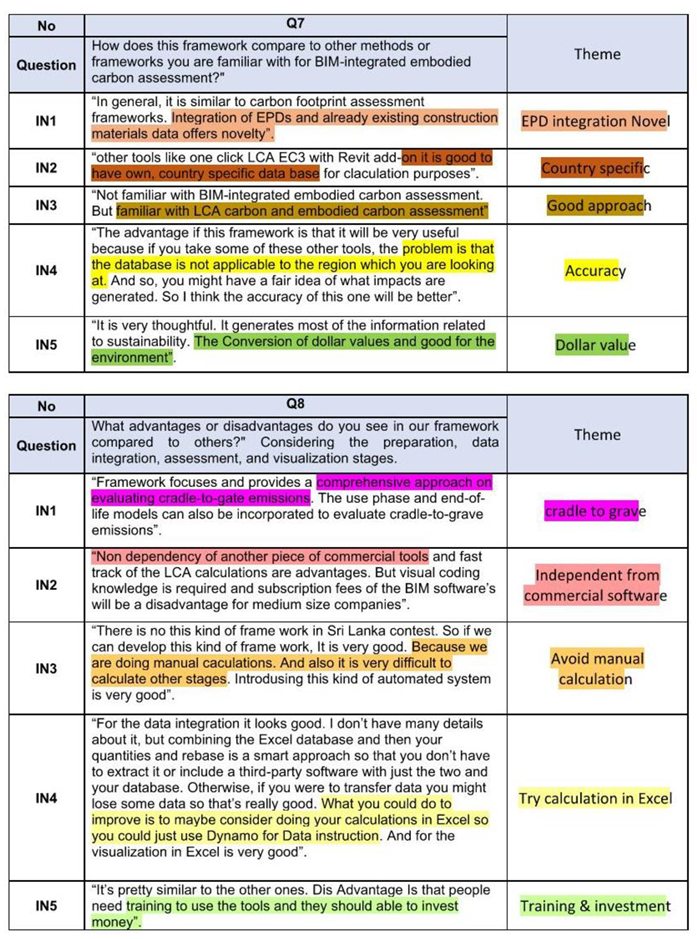

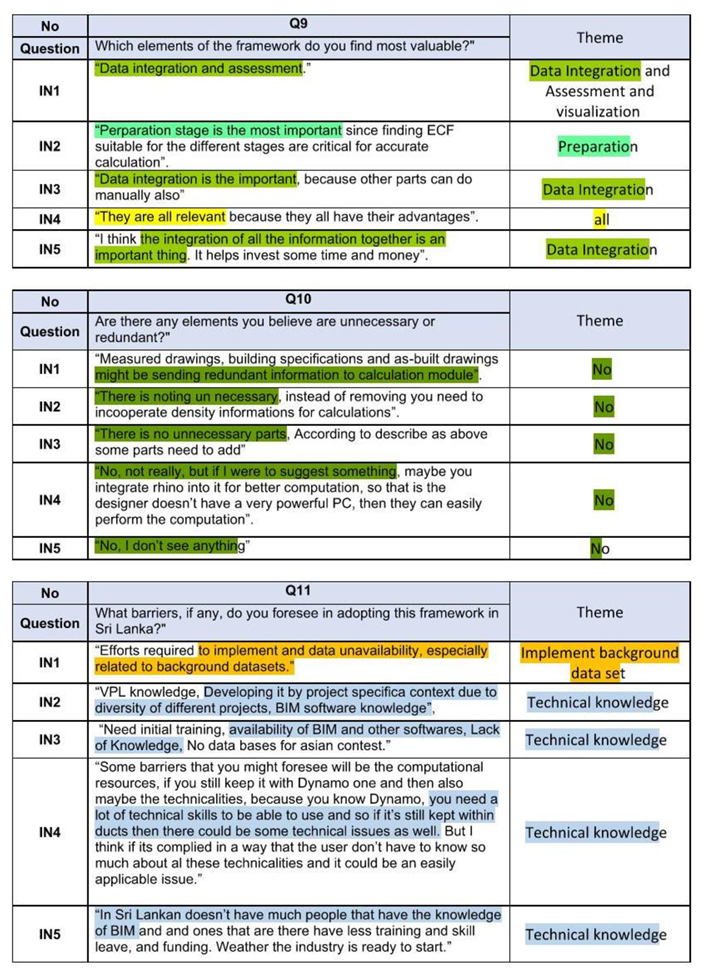

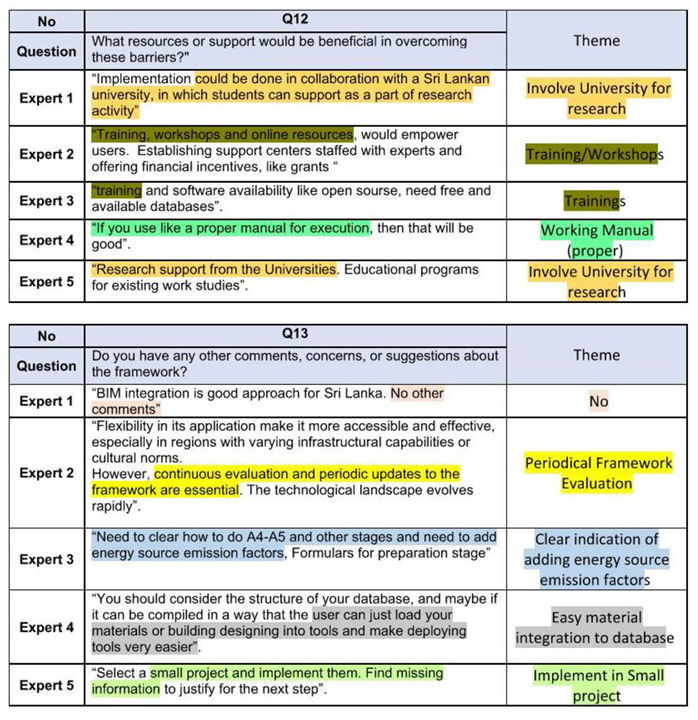

Five experts were interviewed to gather insights and feedback on the developed BIM-LCA integrated framework for assessing environmental compliance in the context of SL.

According to Williams and Lee [

111], experts, defined as ‘knowledge specialists,’ possess technical expertise within a specific field. Von Soest [

112] employed expert interviews to bridge gaps between expert insights and literature findings. The framework, presented for verification, underwent scrutiny through open-ended questions organised into five sections (

Appendix A). Recorded interviews (anonymised as IN1 to IN5) were transcribed and thematically analysed (

Appendix B) to ensure relevance and identify modifications, maintaining participant anonymity while enhancing the framework’s validity. Summary of analysis illustrated in

Figure 18.

4. Discussion

Synthesising SLR findings and expert insights yields a comprehensive framework specifically adapted to Sri Lankan construction industry characteristics (see

Figure 19). This framework addresses the central research question: How can embodied carbon assessments be integrated within BIM frameworks in the Sri Lankan context?

The framework comprises six interconnected modules:

Module 1: Preparation and Goal Definition: This foundational phase establishes clear assessment parameters.

Module 2: Data Infrastructure Development: Establishing reliable EC calculation foundations through BSR enhancement and ECF compilation.

Module 3: BIM Model Development: Creating information-rich digital representations enabling automated quantity extraction.

Module 4: Automated Data Integration via Dynamo: Employing visual programming to link BIM model data with EC calculation logic.

Module 5: Calculation and Analysis: Executing systematic EC quantification across multiple dimensions.

Module 6: Visualisation and Communication: Translating numerical results into actionable insights through multiple presentation modes.

4.1. Key Steps and Elements of Framework

The initial discussion focuses on the development of the framework and its alignment with the research objectives. The first research objective (OBJ-01) involves laying the foundation by identifying existing frameworks. The literature review provides detailed discussions on findings related to OBJ-01, identifying conventional approaches, IFC-based approaches, plug-in-based approaches, and parametric modelling-based approaches. Notably, these approaches are predominantly employed by developed countries with limited application in developing countries. The subsequent step involves identifying key parameters in EC assessment frameworks to enhance precision in understanding critical variables. OBJ-2 aligns with this aspect, and in

Section 3.2, BIM Model Geometry, Material Information, LCA Data, Transportation Data, Building Use and End-of-Life Considerations, Data Interoperability, Data Accuracy and Precision, and Energy Performance Data are identified as key parameters through the analysis.

The content analysis identifies BIM tools, LCA tools, System boundaries and life cycle stages, functional units, and scope, as well as LCA databases, as key variables for exploration in the framework formation. To establish correlations between variables and understand dependencies, the next step is crucial. This helps to comprehend how changes in one aspect may affect others, aiding in the prediction of outcomes or behaviours. Findings reveal positive correlations between BIM software and LCA tools, as well as between BIM software and Country, outlined in

Section 3.7 Other variables showed independence with no correlation.

Consequently, a proposed framework is formulated, and framework verification is conducted by BIM-LCA experts, aligning with OBJ-03 of the research. Objectives 4 (OBJ-04) and 5 (OBJ-05), which focus on identifying the main challenges and barriers and providing guidelines for implementing sustainable construction practices in Sri Lanka for stakeholders, policymakers, and practitioners, are concluded based on outcomes from expert interviews and previous findings.

4.1.1. Preparation

This segment explores the developed framework based on the research findings. In the findings section, cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave system boundaries are prevalent, with an emphasis on addressing all boundaries despite data scarcity. A1-A3 life cycle stages dominate, aligning with Smith and Durham [

113], while challenges in extending beyond cradle-to-gate are noted by Finkbeiner et al. [

114]. The proposed framework targets a Cradle-to-Grave Approach, acknowledging the importance of EC despite existing data limitations. The findings indicate that the predominantly adopted functional unit is square meters. The proposed framework suggests unit conversions, recognising that the LCA scope of evaluation varies across material, component, and building levels. However, research data on the huge popularity of material-level calculations may be due to the availability of LCA databases for these calculations. The proposed framework introduces scripting to select different units and calculate accordingly.

As found in OBJ-01, ECF plays a key role in EC calculations and is included in LCA databases. The proposed framework extracts ECF from three main databases identified in OBJ-03: ICE, ecoinvent, and ÖKOBAUDAT. Using multiple databases reduces data collection efforts and provides high-quality inputs for LCA, addressing challenges highlighted by Chen, Matthews and Griffin [

115]. Although they highlight that different databases may give different results and insights. However, this study argues that in cases where no country-specific databases exist, this method is suitable for developing countries like Sri Lanka. Additionally, the study introduces EPDs for extracting the missing ECFs within the framework. EPDs are often advocated for reporting construction material ECF due to their consistent and reliable environmental information, which aligns with EN 15,804 and EN 978 criteria [

116]. The future is expected to witness increased accessibility of project-specific and country-specific EC data based on EPDs, as anticipated by Eleftheriadis, Duffour and Mumovic [

117].

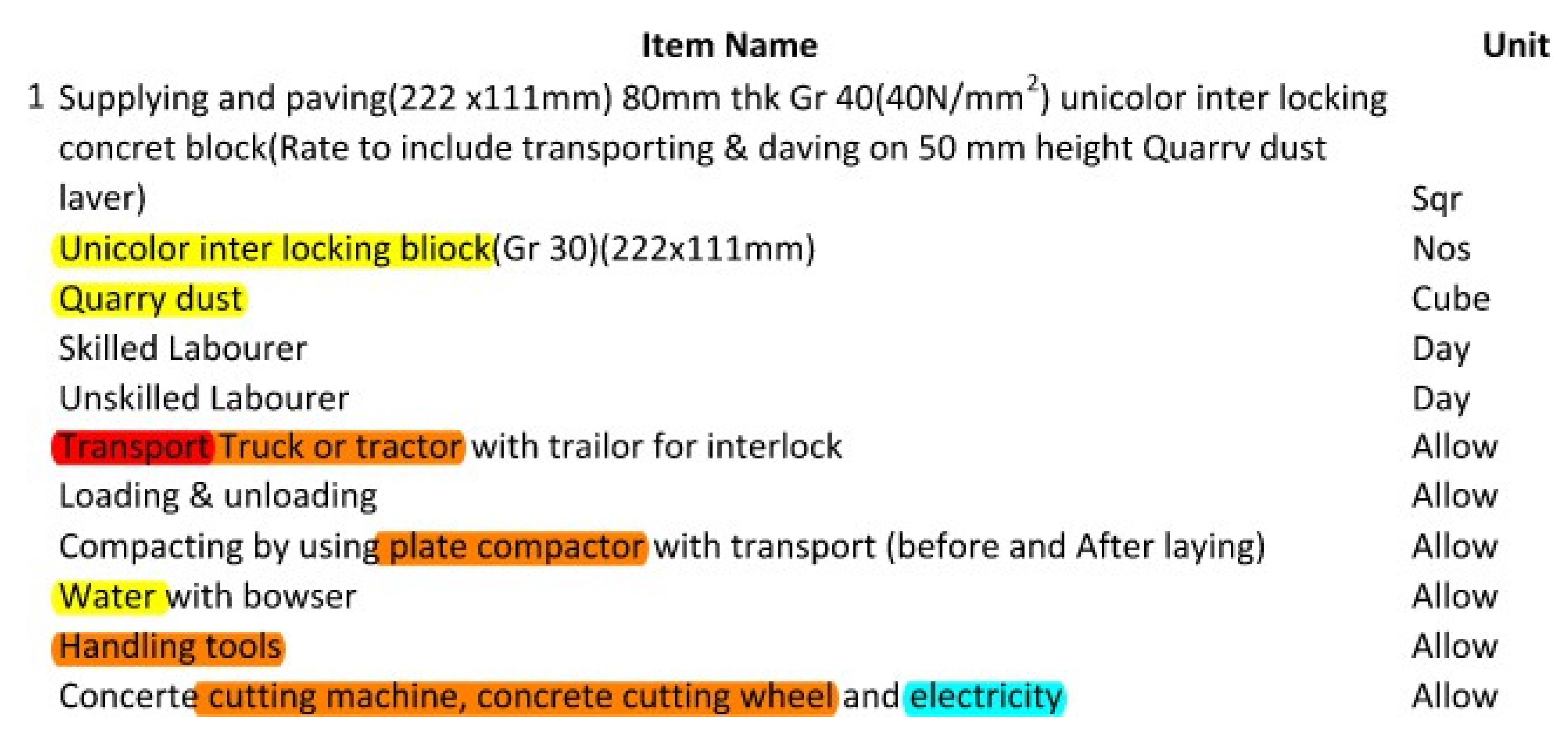

One of the unique aspects of this framework is the development of a BSR into a comprehensive material database enriched with ECFs. The BSR, provided by the Sri Lankan government, serves as a valuable resource for information related to materials. Gomes et al. [

118] contributed to country-specific data efforts. A similar approach is proposed with the BSR to populate the data.

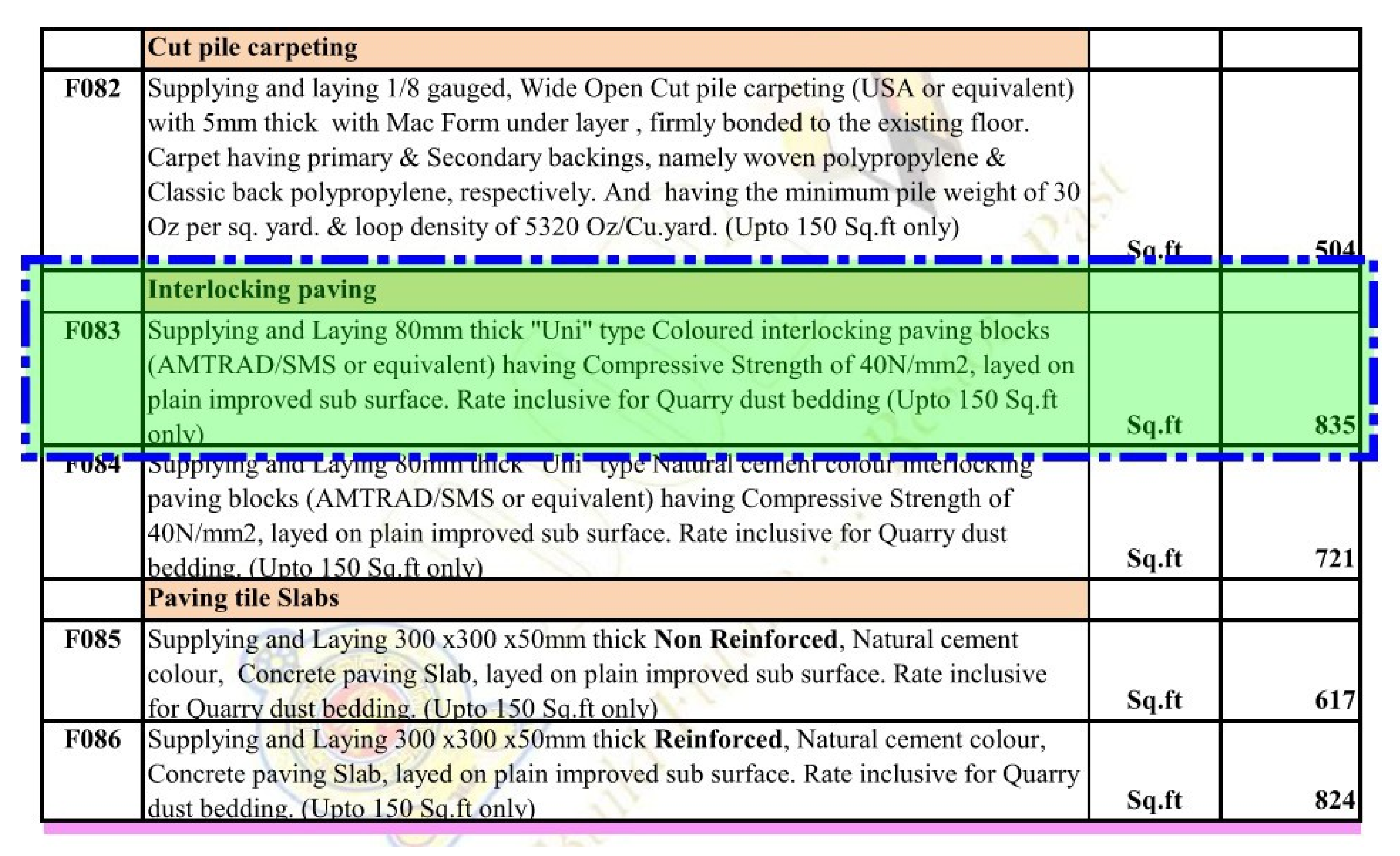

Figure 20 outlines the part extraction of the BSR document, and the item code F083-related material breakdown is illustrated in

Figure 21. It consists of all material data, such as paving blocks and quarry dust, as well as machinery, transportation, and electricity-related data, which are highlighted by different colours.

The final framework was amended to include material density information as stressed by the experts during the interviews. To calculate density, mass must be divided by volume. In BSR calculations, materials are typically quantified by volume, while ECFs are given in mass units (Kg/Ton). Thus, converting material volume to mass is necessary for EC calculations. In the Sri Lankan context, some density-related information is provided in BSR, but it may not cover all materials. In such cases, online sources can be explored for relevant material information.

Similarly, experts emphasise the importance of considering Energy Source Emission Factors (ESEF) in EC assessments, with factors varying according to the energy source [

120]. Renewable sources, such as solar or wind energy, exhibit lower emission factors, while fossil fuel-based sources have higher factors due to the combustion of carbon-rich fuels [

121]. This is crucial, particularly in the construction, in-use, and end-of-life stages, where the Ecoinvent database is widely utilised for comprehensive emission factor data [

40], which is part of the proposed framework and aligns with the expert view.

4.1.2. Data Integration

Moving into the next section of the framework, according to the findings in OBJ-03,

Section 3.3, Revit emerges as the predominant BIM authoring tool globally, particularly in Asia. This tool is crucial in generating BIM models, which serve as the cornerstone for EC calculations. OBJ-01 findings underscore that BIM models can be produced for both new and existing constructions. For new constructions, models require building specifications, often referenced from the ICTAD building specification in the Sri Lankan context. Existing constructions necessitate measured drawings, which may be in CAD files or manual paper drawings and can be imported into the BIM model or created from scratch.

According to the statistical findings, the BIM tool is closely connected to LCA tools. Findings in

Section 3.7 reveal a positive correlation between these variables, with an R

2 value of 0.15, indicating a connection between the two tools. However, 85% of the variation is attributed to unknown factors, suggesting that other requirements, such as economic factors and ease of use, influence tool selection for the framework. Based on

Based on the above facts, the chosen framework selects Revit as the BIM tool and Dynamo scripting as the optimal method for data integration in the Sri Lankan context.

To establish a connection between the Excel file and the Revit model, Dynamo scripts must be created. This particular framework proposed two dynamo scripts for the process. Automating the creation of materials names in the Revit library is the first Dynamo script that automates a time-consuming manual procedure. It utilises RGB colour values and material names stored in an Excel sheet, translating and converting them into the Revit library [

122]. An Excel spreadsheet is generated by extracting material names and unique Revit IDs from the Revit library for constructing a mapped detail of ECF. It maintains the order of rows, retains materials without an EC value, and ensures accuracy through material IDs during data import [

122].

By combining material information from the Excel file and elemental data from calculation scripts, this Dynamo script automatically integrates key parameters into the Revit template. It ensures category inclusion, checks for parameter duplicates, and prevents overlap [

123].

A Dynamo script imports the material parameters of the ‘all materials LCI/ECF database’ into Revit. The script reads, sorts, and imports the Excel file into parameters, making the template ready for use. Dynamo script logic involves defining material categories, extracting data, sorting, and importing parameters. Output is finally displayed. By the end of this step, the BIM model will be completed with all required information and links to the external Excel file for the next step’s calculations.

4.1.3. Assessment and Visualisation

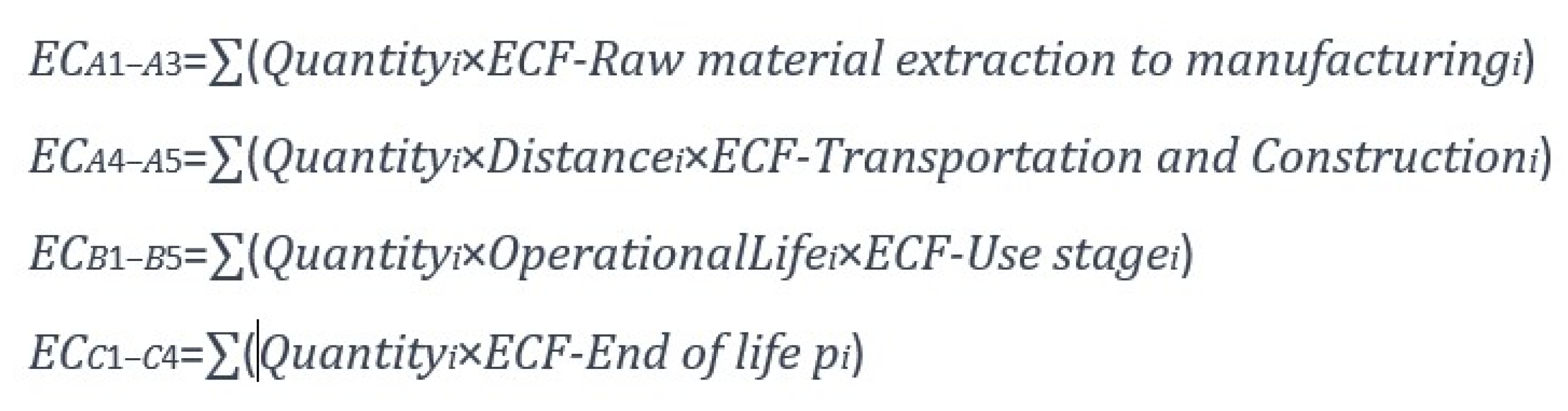

The subsequent phase of the framework involves developing the calculation Dynamo script, encompassing all four stages from A1 to C4, as illustrated in

Figure 19. Specific coding is implemented within Dynamo for various stages of calculations, addressing each phase of the life cycle from A1 to C4. Experts emphasise the computational power required for executing large-scale data within the Dynamo environment. They suggest a potential shift of calculations to the Excel environment as a more efficient solution. Similarly, Weng et al. [

124] propose distributing the code over a cluster of workstations using message-passing software to alleviate the computational demands of Dynamo, although this approach is highly technical. However, more case studies have demonstrated success with Dynamo, making it a viable starting point for developing countries like Sri Lanka.

In the final stage of the framework, the Dynamo script reveals EC amounts. It identifies significant contributors for each element category, adhering to the calculation formulas outlined in

Figure 22. The script computes EC per building using a structured approach and visualises the results using Dynamo [

125]. The Dynamo script thoroughly analyses EC, pinpointing top contributors and validating model accuracy. The collected data are sorted, grouped, and exported to an Excel sheet, allowing users to identify the major contributors per element type within a category.

BIM and EC assessment in Sri Lanka

As per insights derived from expert interviews, several challenges and barriers related to BIM-LCA integrated EC assessment were identified. The first challenge emphasised the complexity of integrating multiple data sources, acknowledging the variability in results from different sources, as noted by Chen, Matthews and Griffin [

115]. Despite potential uncertainties, the primary goal remains taking effective actions to mitigate environmental impact. The second challenge highlighted the unavailability of country-specific datasets for Sri Lanka. Developing such datasets is acknowledged as a meticulous process that involves defining the scope, collecting data from local sources, adapting global databases, consulting experts, considering environmental regulations, maintaining transparent documentation, conducting sensitivity analyses, and providing periodic updates [

127,

128,

129]. While the development of a local dataset is time-consuming, the current reliance on available global data is necessary.

The third challenge highlighted computational issues with Dynamo, specifically the requirement for substantial computational power to handle large projects with extensive datasets. However, literature suggests that the significant acceleration in modelling and documentation processes outweighs this challenge, providing an overall advantage [

130]. The fourth challenge raised concerns about the high cost of BIM software and a shortage of BIM experts in Sri Lanka. Despite this, projections indicate a 5% annual rate of substantial growth in the Sri Lankan construction market between 2024 and 2027potentially changing the BIM landscape in the country [

131]. The fifth challenge focused on obtaining industry consent, disseminating technical knowledge, and providing adequate training. This challenge is indirectly related to the fourth challenge, and there is an expectation that perceptions may shift in response to the changing landscape, as highlighted in the fourth point.

Implications

The practical application of the framework relies significantly on the BSR. For effective implementation, government policy decisions are crucial to populate the BSR document with relevant ECFs, mirroring its annual update. Alternatively, private sector initiatives may be necessary to maintain the BSR document. Concurrently, policy decisions should be enacted to improve the affordability of BIM software, promote BIM-related training, and emphasise sustainability applications. Setting targets for EC in building approvals, once fully implemented, could be explored through policy initiatives. The framework should be further investigated in the context of small projects, with an emphasis on its practical implications. Identifying components that require further improvement and conducting periodic reviews can help enhance the framework’s efficacy.

As emphasised in the literature, B1-B5 and C1-C4 calculations are project-specific and challenging due to the extensive information required. Dixit [

132] underscores the customisation of B1-B5 calculations for maintenance scenarios over a building’s anticipated lifespan, acknowledging variations for different building types. In the case of C1-C4, the availability of fuel consumption data from both tools and transport is identified as a critical requirement [

126]. Consequently, refining the assessment and visualisation aspects of the framework through actual case study applications becomes imperative.

Upon implementation, the framework holds advantages for all stakeholders in the Sri Lankan construction industry, including architects and engineers. Extracting information from the BSR database for calculations creates a standardised approach within the country, making it a promising initiative for advancing sustainable practices in the Sri Lankan context.

5. Conclusions

In response to the growing global imperative to address environmental concerns, particularly in the construction industry, this research endeavours to bridge the gap between sustainable construction practices and the adoption of BIM with a focus on EC assessments. The investigation is contextualised within the framework of SL, a nation experiencing rapid urbanisation and construction growth.

Aligned with the United Nations’ 2015 Sustainable Development Goals, the study recognises the potential of low-carbon materials and innovative technologies to contribute to economic and environmental advancements. In the construction industry, BIM emerges as one of the most critical technological innovations. The integration of BIM into sustainable construction practices represents an underexplored area, especially in developing countries like Sri Lanka.

The research questions and objectives are formulated to address the adaptation of BIM methodologies to diverse construction practices, the integration of key parameters for EC assessment, and the identification and addressing of barriers and challenges to implementing a comprehensive conceptual framework. The empirical findings from the SLR provide insights into the current landscape of BIM-integrated EC assessments. Notably, there is a growing interest, as evidenced by the increasing number of publications in recent years. The identified key variables include BIM tools, LCA tools, system boundaries, life cycle stages, functional units, scope, and LCA databases. Building upon the identified variables, the study proposes a robust conceptual framework tailored for the Sri Lankan construction sector. The framework encompasses three critical stages: preparation, data integration, and assessment & visualisation.

The dynamo scripting approach, particularly utilising Revit and Dynamo, is chosen for data integration, acknowledging the prominence of Revit as a BIM authoring tool globally. The framework also emphasises the importance of material density and the extraction of EPDs and data extraction from multiple databases. The framework undergoes validation through expert interviews, adding a qualitative layer to the research. While they validate the framework, experts identify challenges related to data source integration, the absence of country-specific datasets, computational demands, cost implications, and the need for industry-wide awareness and training. These challenges highlight the multifaceted nature of implementing sustainable construction practices, which necessitate collaboration among stakeholders, policy interventions, and advancements in technology. The implications of the research extend beyond academic discourse to practical applications. The framework’s effectiveness hinges on the government’s commitment to maintaining and updating the BSR document with relevant ECFs. Private sector initiatives are also vital for sustaining this database. This study suggests potential policy initiatives, such as setting targets for EC in building approvals and enhancing the affordability of BIM software.

The framework’s practical application should be the focus of future research. Continuous refinement and periodic reviews are essential to enhance its efficacy. Addressing project-specific challenges, particularly in stages B1-B5 and C1-C4, requires further investigation and customisation for different building types and maintenance scenarios. Overall, this research provides a comprehensive and tailored approach to integrating BIM with EC assessments in the context of Sri Lanka. It serves as a foundation for sustainable construction practices, offering valuable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and industry stakeholders. As the global construction landscape evolves, the adoption of such frameworks becomes imperative for a sustainable and environmentally conscious future for Sri Lanka.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Talpe Pandithawattage Anuradha Lasantha Piyas; writing—review and editing, supervision, and project administration, Ahmed Hagras & Amalka Nawarathna; conceptualisation and Data collection, Talpe Pandithawattage Anuradha Lasantha Piyas; Reviews and supervision, Marianthi Leon, Karina Silverio & Abhinesh Prabhakaran. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIM |

Building Information Modelling |

| BoQ |

Bills of Quantities |

| BSR |

Building Schedule of Rates |

| EC |

Embodied Carbon |

| ECF |

Embodied Carbon Factors |

| EPD |

Environmental Product Declarations |

| GHG |

Green House Gas |

Appendix A. Interview Guideline

Appendix B—Qualitative Data Analysis

References

- M. Płoszaj-Mazurek and E. Ryńska, ‘Artificial Intelligence and Digital Tools for Assisting Low-Carbon Architectural Design: Merging the Use of Machine Learning, Large Language Models, and Building Information Modeling for Life Cycle Assessment Tool Development’, Energies , vol. 17, no. 12, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. S. S. Lima, S. Duarte, H. Exenberger, G. Fröch, and M. Flora, ‘Integrating BIM-LCA to Enhance Sustainability Assessments of Constructions’, Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 3, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Lützkendorf and M. Balouktsi, ‘Embodied carbon emissions in buildings: explanations, interpretations, recommendations’, Buildings and Cities, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 964–973, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Rondinel-Oviedo and N. Keena, ‘Embodied Carbon: A call to the building industry’, IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 1122, no. 1, p. 012042, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. H. U. W. Abeydeera, J. W. Mesthrige, and T. I. Samarasinghalage, ‘Perception of Embodied Carbon Mitigation Strategies: The Case of Sri Lankan Construction Industry’, Sustainability 2019, Vol. 11, Page 3030, vol. 11, no. 11, p. 3030, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Perera and R. Palliyaguru, ‘Adapting the standard forms of contract to minimize the contractual effects of COVID-19 on construction projects’, pp. 76–88, 2022. [CrossRef]

- CHEC Port City Colombo (Pvt) Ltd., ‘About Port City Colombo—Sri Lanka’s Global Business Hub’. Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.portcitycolombo.lk/about-port-city-colombo/.

- A. P. K. D. Mendis1 et al., ‘Implementation of government policies in the construction industry: The case of Sri Lanka’, ITU A|Z •, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 151–167, 2022,. [CrossRef]

- S. Gunathilake, T. Ramachandra, and U. G. D. Madushika, ‘Carbon footprint analysis of construction activities in sri lanka: an input‒output table’, in 14th International Research Conference—FARU 2021, 2021.

- I. A. Amarasinghe, D. Soorige, and D. Geekiyanage, ‘Comparative study on Life Cycle Assessment of buildings in developed countries and Sri Lanka’, Built Environment Project and Asset Management, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 304–329, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Nadeeshani, T. Ramachandra, S. Gunatilake, and N. Zainudeen, ‘Carbon Footprint of Green Roofing: A Case Study from Sri Lankan Construction Industry’, Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 6745, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 6745, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Nawarathna, Z. Alwan, B. Gledson, and N. Fernando, ‘Embodied carbon in commercial office buildings: Lessons learned from Sri Lanka’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 42, p. 102441, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumanayake, H. Luo, and N. Paulusz, ‘Assessment of material related embodied carbon of an office building in Sri Lanka’, Energy Build, vol. 166, pp. 250–257, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Kumari, U. Kulathunga, T. Hewavitharana, and N. Madusanka, ‘Embodied carbon reduction strategies for high-rise buildings in Sri Lanka’, International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 22, no. 13, pp. 2605–2613, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Hadjiiski et al., ‘The Evolution of Life Cycle Assessment Approach: A Review of Past and Future Prospects’, IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 992, no. 1, p. 012002, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Teng, W. Pan, and Y. Zhang, ‘BIM-integrated LCA to automate embodied carbon assessment of prefabricated buildings’, J Clean Prod, vol. 374, p. 133894, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Hussain, B. Zheng, H. L. Chi, and S. C. Hsu, ‘Automated and continuous BIM-based life cycle carbon assessment for infrastructure design projects’, Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 190, p. 106848, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. D. R. R. Rosayuru, K. G. A. S. Waidyasekara, and M. K. C. S. Wijewickrama, ‘Sustainable BIM based integrated project delivery system for construction industry in Sri Lanka’, International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 769–783, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. A. H. H. Kaushalya, M. Thayaparan, L. N. K. Weerasinghe, and A. Attfield, ‘Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory to enhance BIM implementation in the construction industry of Sri Lanka’, Intelligent Buildings International, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 182–198, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Manoharan, P. Dissanayake, C. Pathirana, D. Deegahawature, and R. Silva, ‘Labour-related factors affecting construction productivity in Sri Lankan building projects: perspectives of engineers and managers’, Frontiers in Engineering and Built Environment, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 218–232, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Manoharan, P. B. G. Dissanayake, C. Pathirana, D. Deegahawature, and K. D. R. R. Silva, ‘A curriculum guide model to the next normal in developing construction supervisory training programmes’, Built Environment Project and Asset Management, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 792–822, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Rabiser, P. Grünbacher, and D. Dhungana, ‘Requirements for product derivation support: Results from a systematic literature review and an expert survey’, Inf Softw Technol, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 324–346, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Tugwell and D. Tovey, ‘PRISMA 2020’, J Clin Epidemiol, vol. 134, pp. A5–A6, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Pomponi and A. Moncaster, ‘Embodied carbon mitigation and reduction in the built environment—What does the evidence say?’, J Environ Manage, vol. 181, pp. 687–700, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Karimi and I. Iordanova, ‘Integration of BIM and GIS for Construction Automation, a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) Combining Bibliometric and Qualitative Analysis’, vol. 1, p. 3. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Dangelico, ‘Green Product Innovation: Where we are and Where we are Going’, Bus Strategy Environ, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 560–576, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Deng and H. Smyth, ‘Contingency-Based Approach to Firm Performance in Construction: Critical Review of Empirical Research’, J Constr Eng Manag, vol. 139, no. 10, p. 04013004, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D. G. Altman, ‘Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement’, International Journal of Surgery, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 336–341, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, ‘Journal and disciplinary variations in academic open peer review anonymity, outcomes, and length’, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 299–312, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. Rosyidah, S. Sudarmiatin, and H. Sumarsono, ‘Digitalization and internationalization of SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review’, Journal of Enterprise and Development (JED), vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 479–499, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Eduardo Celestino Andrade, E. Gonzaga Lima Neto, F. Sandro Rodrigues, L. Diego Vidal Santos, L. Celestino de Andrade Júnior, and A. Abade Bandeira, ‘An analysis of overlapping terms to define articles key words: The use of VOSviewer tool applied to technology transfer in fuel cells’, International Journal for Innovation Education and Research www.ijier.net, no. 08, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Nellessen et al., ‘Characterization of Human Papilloma Virus in Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy—A Prospective Study of 140 Patients’, Viruses, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 1264, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Hegazy, K. Yasufuku, and H. Abe, ‘Evaluating and visualizing perceptual impressions of daylighting in immersive virtual environments’, Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 768–784, Nov 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. N. K. Soysa, A. S. Kumara, D. M. Jayasena, and M. K. S. M. Samaranayake, ‘Exploring major reported themes in corporate sustainability disclosures integrating the sustainable development goals: an analysis of Sri Lankan listed rms’, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. De Jong and D. Bus, ‘VOSviewer: putting research into context. Research Software Community Leiden 2023’, 2023.

- Z. Chen, S. S. Yu Lau, Z. Zhang, S. S. Yeung Lau, and T. Kee, ‘A modular framework for estimating carbon emissions from building component replacements in LCA’, Energy Build, vol. 349, p. 116424, Dec 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Soust-Verdaguer, A. García-Martínez, B. Rey-Álvarez, B. de Diego, A. de la Fuente, and M. Röck, ‘Data infrastructure for whole-life carbon emissions baselines of buildings in Spain’, Energy Build, vol. 347, Nov 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Xu, J. Chen, and J. I. Kim, ‘An integrated LCA–BIM framework for assessing carbon emissions in buildings in China’s cold regions’, J Clean Prod, vol. 522, Sep 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, J. Wang, R. Zhang, Q. Bi, and J. Pan, ‘Application of Prefabricated Public Buildings in Rural Areas with Extreme Hot–Humid Climate: A Case Study of the Yongtai County Digital Industrial Park, Fuzhou, China †’, Buildings, vol. 15, no. 15, Aug 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, X. Gong, X. Tao, H. H. L. Kwok, C. Limsawasd, and J. C. P. Cheng, ‘Automated openBIM-based discrete event simulation modeling for cradle-to-site embodied carbon assessment’, Autom Constr, vol. 175, Jul 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Borkowski, U. Hajdukiewicz, J. Herbich, K. Kostana, and A. Kubala, ‘Analysis of the Tools for Evaluating Embodied Energy Through Building Information Modeling Tools: A Case Study of a Single-Unit Shell Building’, Earth (Switzerland), vol. 6, no. 2, Jun 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Y. Zha, M. Li, and L. Qian, ‘Evaluating the carbon footprint of a hospital from the dynamic life cycle perspective:A case study in Shanghai’, Build Environ, vol. 277, Jun 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Baskaran, U. Chockkalingam, and R. Senthil Muthalvan, ‘Assessment of Sustainable Hybrid Formwork Systems Using Life Cycle Assessment and the Wear-Out Coefficient—A Case Study’, Buildings, vol. 15, no. 10, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, L. Gao, X. Zhang, H. Xu, and L. Jiang, ‘Research on Building’s Carbon Emission Calculation and Reduction Strategy Based on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Building in Formation Modeling (BIM): A Case Study in Beijing, China’, Buildings, vol. 15, no. 9, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Sistos-Sescosse, B. T. Atuahene, O. Ajulo, and I. Adams, ‘Examining the Decision Criteria for BIM–LCA: A Case Study’, Construction Economics and Building, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 203–220, Apr 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiang, G. Li, and H. Li, ‘A Common Data Environment Framework Applied to Structural Life Cycle Assessment: Coordinating Multiple Sources of Information’, Buildings, vol. 15, no. 8, Apr 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Strelets, D. Zaborova, D. Kokaya, M. Petrochenko, and E. Melekhin, ‘Building Information Modeling (BIM)-Based Building Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Using Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) File Format’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 17, no. 7, Apr 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Gu, C. Chen, Y. Fang, R. Mahabir, and L. Fan, ‘CECA: An intelligent large-language-model-enabled method for accounting embodied carbon in buildings’, Build Environ, vol. 272, Mar 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Fernández Rodríguez, A. Picardo, T. Aguilar-Planet, A. Martín-Mariscal, and E. Peralta, ‘Data Transfer Reliability from Building Information Modeling (BIM) to Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—A Comparative Case Study of an Industrial Warehouse’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 17, no. 4, Feb 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. M. Al-Zrigat, ‘BIM framework to minimize embodied energy in heritage buildings: old downtown Amman case studies’, Facilities, vol. 43, no. 1–2, pp. 149–171, Jan 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohammed, I. Elmasoudi, and M. Ghannam, ‘Life cycle environmental impact assessment of steel structures using building information modeling’, Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. T. H. A. Ferreira, A. A. Costa, and J. D. Silvestre, ‘Environmental optimization and benchmarking of walls through a BIM plugin’, Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ding, Z. Z. Guo, S. X. Zhou, Y. Q. Wei, A. M. She, and J. L. Dong, ‘Research on carbon emissions during the construction process of prefabricated buildings based on BIM and LCA’, Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 1426–1438, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Lv, ‘A carbon footprint evaluation model for the entire life cycle of building materials—case study’, Archives of Civil Engineering, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 63–81, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Safari and S. Ghandehariun, ‘An integrative BIM-based life cycle assessment framework to address uncertainties: a mixed-methods study under real construction project context’, International Journal of Construction Management, 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Samniang, K. Panuwatwanich, S. Tangtermsirikul, and S. Papong, ‘Development and implementation of BIM-integrated LCA method for carbon emission assessment of concrete construction: case of overpass project in Thailand’, Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pandimani, P. Bilgates, and Y. Raviteja, ‘A holistic design approach for sustainable building environment–a case study of an educational building’, International Journal of Construction Management, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yardımcı, B. B. Colak Demirel, and M. Ertosun Yıldız, ‘Climatic Influences on the Environmental Performances of Residential Buildings: A Comparative Case Study in Turkey’, Buildings, vol. 14, no. 12, Dec 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Kathiravel and H. Feng, ‘Structural and embodied carbon performance optimization for low carbon buildings through BIM-based integrated design’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 98, Dec 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Aragón and M. G. Alberti, ‘Limitations of machine-interpretability of digital EPDs used for a BIM-based sustainability assessment of construction assets’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 96, Nov 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Parece, R. Resende, and V. Rato, ‘A BIM-based tool for embodied carbon assessment using a Construction Classification System’, Developments in the Built Environment, vol. 19, Oct 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Abdelaal, S. M. Seif, M. M. El-Tafesh, N. Bahnas, M. M. Elserafy, and E. S. Bakhoum, ‘Sustainable assessment of concrete structures using BIM–LCA–AHP integrated approach’, Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 25669–25688, Oct 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. A. M. M. Ali, ‘Cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment of interior floor material alternatives in Egypt’, Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Engineering and Architecture, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 282–297, Sep 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Manifold, S. Renukappa, S. Suresh, P. Georgakis, and G. R. Perera, ‘Dual Transition of Net Zero Carbon and Digital Transformation: Case Study of UK Transportation Sector’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 17, Sep 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao et al., ‘Carbon Emission Analysis of RC Core Wall-Steel Frame Structures’, Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 17, Sep 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ş. Atik, T. D. Aparisi, and R. Raslan, ‘Mind the gap: Facilitating early design stage building life cycle assessment through a co-production approach’, J Clean Prod, vol. 464, Jul 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Ullah, H. Zhang, H. Ye, I. Ali, and M. Cong, ‘Research on Low-Carbon Design and Energy Efficiency by Harnessing Indigenous Resources through BIM-Ecotect Analysis in Hot Climates’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 14, Jul 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Han et al., ‘BIM-Based Analysis and Strategies to Reduce Carbon Emissions of Underground Construction in Public Buildings: A Case on Xi’an Shaanxi, China’, Buildings, vol. 14, no. 7, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Yavan, R. Maalek, and V. Toğan, ‘Structural Optimization of Trusses in Building Information Modeling (BIM) Projects Using Visual Programming, Evolutionary Algorithms, and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Tools’, Buildings, vol. 14, no. 6, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Eslami, A. H. Eslami, A. Yaghma, L. B. Jayasinghe, and D. Waldmann, ‘Comparative life cycle assessment of light frame timber and reinforced concrete masonry structural systems for single-family houses in Luxembourg’, Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Kylili, P. Z. Georgali, P. Christou, and P. Fokaides, ‘An integrated building information modeling (BIM)-based lifecycle-oriented framework for sustainable building design’, Construction Innovation, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 492–514, Feb . 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Topraklı, ‘Enabling circularity in Turkish construction: a case of BIM-based material management utilizing material passports’, Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Danso et al., ‘Analysis of the underlying factors affecting BIM-LCA integration in the Ghanaian construction industry: a factor analysis approach’, Construction Innovation, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Sugiyama, M. F. Rodrigues, and H. Rodrigues, ‘Environmental impacts and BIM: a Portuguese heritage case study’, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Ma, R. Azari, and M. Elnimeiri, ‘A Building Information Modeling-Based Life Cycle Assessment of the Embodied Carbon and Environmental Impacts of High-Rise Building Structures: A Case Study’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 2, Jan. 2024. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Forth, J. Abualdenien, and A. Borrmann, ‘Calculation of embodied GHG emissions in early building design stages using BIM and NLP-based semantic model healing’, Energy Build, vol. 284, p. 112837, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Boje et al., ‘A framework using BIM and digital twins in facilitating LCSA for buildings’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 76, p. 107232, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, L. Guante Henriquez, G. Dotelli, and M. Imperadori, ‘Holistic Approach for Assessing Buildings’ Environmental Impact and User Comfort from Early Design: A Method Combining Life Cycle Assessment, BIM, and Active House Protocol’, Buildings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1315, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 1315, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Arvizu-Piña, J. F. Armendáriz López, A. A. García González, and I. G. Barrera Alarcón, ‘An open access online tool for LCA in building’s early design stage in the Latin American context. A screening LCA case study for a bioclimatic building’, Energy Build, vol. 295, p. 113269, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Yevu, E. K. Owusu, A. P. C. Chan, K. Oti-Sarpong, I. Y. Wuni, and M. O. Tetteh, ‘Systematic review on the integration of building information modelling and prefabrication construction for low-carbon building delivery’, Building Research and Information, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 279–300, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Hunt and C. A. Osorio-Sandoval, ‘Assessing Embodied Carbon in Structural Models: A Building Information Modelling-Based Approach’, Buildings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1679, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 1679, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Mowafy, M. El Zayat, and M. Marzouk, ‘Parametric BIM-based life cycle assessment framework for optimal sustainable design’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 75, p. 106898, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Feng, M. Kassem, D. Greenwood, and O. Doukari, ‘Whole building life cycle assessment at the design stage: a BIM-based framework using environmental product declaration’, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 109–142, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Serrano-Baena, C. Ruiz-Díaz, P. G. Boronat, and P. Mercader-Moyano, ‘Optimising LCA in complex buildings with MLCAQ: A BIM-based methodology for automated multi-criteria materials selection’, Energy Build, vol. 294, p. 113219, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Guignone, J. L. Calmon, D. Vieira, and A. Bravo, ‘BIM and LCA integration methodologies: A critical analysis and proposed guidelines’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 73, p. 106780, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Soust-Verdaguer, J. A. Gutiérrez, and C. Llatas, ‘Development of a Plug-In to Support Sustainability Assessment in the Decision-Making of a Building Envelope Refurbishment’, Buildings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1472, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 1472, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Klumbyte et al., ‘Enhancing whole building life cycle assessment through building information modelling: Principles and best practices’, Energy Build, vol. 296, p. 113401, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Deng and K. Lu, ‘Multi-level assessment for embodied carbon of buildings using multi-source industry foundation classes’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 72, p. 106705, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Tavares and F. Freire, ‘Life cycle assessment of a prefabricated house for seven locations in different climates’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 53, p. 104504, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Soust-Verdaguer, I. Bernardino Galeana, C. Llatas, M. V. Montes, E. Hoxha, and A. Passer, ‘How to conduct consistent environmental, economic, and social assessment during the building design process. A BIM-based Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment method’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 45, p. 103516, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Onososen and I. Musonda, ‘Barriers to BIM-Based Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Buildings: An Interpretive Structural Modelling Approach’, Buildings 2022, Vol. 12, Page 324, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 324, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Viscuso, C. Monticelli, A. Ahmadnia, and A. Zanelli, ‘Integration of life cycle assessment and life cycle costing within a BIM-based environment’, Frontiers in Sustainability, vol. 3, p. 1002257, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. juan Li, W. jun Xie, L. Xu, L. lu Li, C. Y. Jim, and T. bing Wei, ‘Holistic life-cycle accounting of carbon emissions of prefabricated buildings using LCA and BIM’, Energy Build, vol. 266, p. 112136, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Alotaibi, S. A. Khan, M. A. Abuhussain, N. Al-Tamimi, R. Elnaklah, and M. A. Kamal, ‘Life Cycle Assessment of Embodied Carbon and Strategies for Decarbonization of a High-Rise Residential Building’, Buildings 2022, Vol. 12, Page 1203, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 1203, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Abdelaal and B. H. W. Guo, ‘Stakeholders’ perspectives on BIM and LCA for green buildings’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 48, p. 103931, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. M. A. Morsi, W. S. E. Ismaeel, A. Ehab, and A. A. E. Othman, ‘BIM-based life cycle assessment for different structural system scenarios of a residential building’, Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 101802, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Sameer and S. Bringezu, ‘Building information modelling application of material, water, and climate footprint analysis’, Building Research and Information, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 593–612, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Alwan, A. Nawarathna, R. Ayman, M. Zhu, and Y. ElGhazi, ‘Framework for parametric assessment of operational and embodied energy impacts utilising BIM’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 42, p. 102768, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Sobhkhiz, H. Taghaddos, M. Rezvani, and A. M. Ramezanianpour, ‘Utilization of semantic web technologies to improve BIM-LCA applications’, Autom Constr, vol. 130, p. 103842, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Hao et al., ‘Carbon emission reduction in prefabrication construction during materialization stage: A BIM-based life-cycle assessment approach’, Science of the Total Environment, vol. 723, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. van Eldik, F. Vahdatikhaki, J. M. O. dos Santos, M. Visser, and A. Doree, ‘BIM-based environmental impact assessment for infrastructure design projects’, Autom Constr, vol. 120, p. 103379, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Durão, A. A. Costa, J. D. Silvestre, R. Mateus, R. Santos, and J. de Brito, ‘Current Opportunities and Challenges in the Incorporation of the LCA Method in BIM’, The Open Construction & Building Technology Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 336–349, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Hollberg, G. Genova, and G. Habert, ‘Evaluation of BIM-based LCA results for building design’, Autom Constr, vol. 109, p. 102972, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Santos, A. A. Costa, J. D. Silvestre, and L. Pyl, ‘Integration of LCA and LCC analysis within a BIM-based environment’, Autom Constr, vol. 103, pp. 127–149, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Nizam, C. Zhang, and L. Tian, ‘A BIM based tool for assessing embodied energy for buildings’, Energy Build, vol. 170, pp. 1–14, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Bueno and M. M. Fabricio, ‘Comparative analysis between a complete LCA study and results from a BIM-LCA plug-in’, Autom Constr, vol. 90, pp. 188–200, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Eleftheriadis, P. Duffour, and D. Mumovic, ‘BIM-embedded life cycle carbon assessment of RC buildings using optimised structural design alternatives’, Energy Build, vol. 173, pp. 587–600, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Najjar, K. Figueiredo, M. Palumbo, and A. Haddad, ‘Integration of BIM and LCA: Evaluating the environmental impacts of building materials at an early stage of designing a typical office building’, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 14, pp. 115–126, Nov. 2017. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Schober and L. A. Schwarte, ‘Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation’, Anesth Analg, vol. 126, no. 5, pp. 1763–1768, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Udovičić, K. Baždarić, L. Bilić-Zulle, and M. Petrovečki, ‘What we need to know when calculating the coefficient of correlation?’, Biochem Med (Zagreb), vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 10–15, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. Williams and J. Lee, ‘Experts, expertise and health and physical education teaching: A scoping review of conceptualisations’, Curric J, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 14–27, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Von Soest, ‘Why Do We Speak to Experts? Reviving the Strength of the Expert Interview Method’, Perspectives on Politics, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 277–287, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Smith and S. A. Durham, ‘A cradle to gate LCA framework for emissions and energy reduction in concrete pavement mixture design’, International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 23–33, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Finkbeiner et al., ‘Challenges in Life Cycle Assessment: An Overview of Current Gaps and Research Needs’, pp. 207–258, 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, H. S. Matthews, and W. M. Griffin, ‘Uncertainty caused by life cycle impact assessment methods: Case studies in process-based LCI databases’, Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 172, p. 105678, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Feng, M. Kassem, D. Greenwood, and O. Doukari, ‘Whole building life cycle assessment at the design stage: a BIM-based framework using environmental product declaration’, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 109–142, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Eleftheriadis, P. Duffour, and D. Mumovic, ‘BIM-embedded life cycle carbon assessment of RC buildings using optimised structural design alternatives’, Energy Build, vol. 173, pp. 587–600, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J. D. Silvestre, J. de Brito, and S. Lasvaux, ‘Environmental datasets for cement and steel rebars to be used as generic for a national context’, J Clean Prod, vol. 316, p. 128003, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- BSR, ‘Building Schedule of Rates For Urgent Special Repairs, Renovations, Additions and Improvements, Minor Works and Maintenance to Government Buildings-2023 Department of Buildings’, 2023.

- Y. Zhao, L. Ma, Z. Li, and W. Ni, ‘A Calculation and Decomposition Method Embedding Sectoral Energy Structure for Embodied Carbon: A Case Study of China’s 28 Sectors’, Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 2593, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 2593, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V.; Khaligh et al., ‘A Comparative Perspective of the Effects of CO2 and Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gas Emissions on Global Solar, Wind, and Geothermal Energy Investment’, Energies 2023, Vol. 16, Page 3025, vol. 16, no. 7, p. 3025, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Hollberg, G. Genova, and G. Habert, ‘Evaluation of BIM-based LCA results for building design’, Autom Constr, vol. 109, p. 102972, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. van Eldik, F. Vahdatikhaki, J. M. O. dos Santos, M. Visser, and A. Doree, ‘BIM-based environmental impact assessment for infrastructure design projects’, Autom Constr, vol. 120, p. 103379, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Weng et al., ‘Extracting BIM Information for Lattice Toolpath Planning in Digital Concrete Printing with Developed Dynamo Script: A Case Study’, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering, vol. 35, no. 3, p. 05021001, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Hunt and C. A. Osorio-Sandoval, ‘Assessing Embodied Carbon in Structural Models: A Building Information Modelling-Based Approach’, Buildings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1679, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 1679, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Abouhamad and M. Abu-Hamd, ‘Life Cycle Assessment Framework for Embodied Environmental Impacts of Building Construction Systems’, Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 461, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 461, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. de Saxcé, A. Perwuelz, and B. Rabenasolo, ‘Development of data base for simplified Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Textiles’, 2011.