1. Introduction

In the context of global warming, the green energy transition has become essential to reduce CO₂ emissions. As a result, offshore wind farms (OWFs) have gained significant attention from energy companies. With the increasing number of OWF implementation projects, it is crucial to assess their potential impacts on local marine ecosystems. One of the main concerns associated with OWFs is underwater noise emissions, which may pose serious threats to marine life [

1]. Numerous studies have investigated the effects of anthropogenic noise on various marine species, and the scientific community continues to work on identifying the thresholds that trigger harmful effects or behavioral changes in different organisms [

1,

2]. In parallel, researchers are analyzing the specific source levels (SL) emitted by different wind turbines. Noise spectrum prediction algorithms based on principal component analysis (PCA) combined with Gaussian process regression bridge knowledge gaps by enabling the prediction of SL spectra across different wind speeds [

3]. Furthermore, noise propagation models, such as Range-dependent Acoustic Model (RAM) [

4] and Bellhop [

5], can estimate how sound disperses throughout the surrounding marine environment. However, integrating these models with SL prediction tools and ecological data remains complex, making it challenging to assess the underwater acoustic impact of specific OWF projects realistically and comprehensively.

To address this gap, we developed an integrated tool that combines SL spectrum prediction [

3] with publicly available propagation models (RAM and Bellhop), all within a Jupyter Notebook framework. This tool allows for the estimation of the sound pressure level (SPL) spectrum at receiver locations, generated by multiple turbines from an OWF. In addition, the notebook incorporates known audiograms and weighting functions for various marine species [

2] to evaluate potential biological impacts by comparing them to the predicted SPLs.

In this study, we apply the described prediction and propagation tool to four planned OWF regions: one in Granadilla, Tenerife [

6], one in Tarahal, Gran Canaria [

7]

, one in the Princess Elisabeth I zone, Belgium [

8]

, and the last one in the N10.2 area, Germany [

9]. We finally assess the cumulative effects of noise from OWF turbines on ecologically sensitive areas.

Due to the limited availability of baseline underwater ambient noise data in the region, we rely on canonical SPL curves to compare with our results [

10]. This approach allows us to evaluate whether OWF-generated noise represents a significant additional acoustic input compared to existing ambient ocean noise levels.

2. Materials and Methods

Working Scheme

We implemented the prediction and propagation models in a Jupyter Notebook to streamline the acoustic assessment process. We input wind speed (see

Operational wind speed) values corresponding to turbine operation into the SL prediction model [

3]. We then compute the one-third octave bands and apply spherical back-propagation to estimate the SL spectrum.

We estimate the Transmission Loss (TL) for each target frequency using RAM model. In this study, because the available source spectrum only extends to 500 Hz, we use this model, which is suitable for frequencies below 1 kHz.

We define all turbine and receiver positions, along with acoustic model parameters and sediment type. Bathymetric profiles were downloaded iteratively from EMODnet [

11] through the ERDDAP server. We calculated the sound speed profile using the empirical equation from [

12], based on local temperature and salinity data (see

Sound speed profile).

After computing the propagation for each source-receiver pair, we calculated the received SPL using the sonar equation.

We then summed contributions from all turbines to estimate cumulative SPL at each receiver location, using the equation derived from the SPL definition.

To evaluate biological impacts, we compared SPL results with species-specific audiograms and weighting functions from [

2]. While this comparison is illustrative and includes only a limited number of species (see

Table 1), it provides insight into potential ecological effects.

Finally, we compared our modeled SPL spectra with representative background noise levels from [

10] curves to assess whether OWF noise surpasses the heavy-marine-traffic, the usual-marine-traffic, and the wind-dependent bubble and spray noise levels.

Our Jupyter Notebook uses some state-of-the-art specialized tools, including

pyRAM [

13],

BELLHOP [

14],

Arlpy [

15], the

Copernicus Marine Toolbox API – Subset [16] and

ERDDAPY [

17] libraries for oceanographic data retrieval and server access.

Operational Wind Speed

To adopt the most conservative case scenario, we use the maximum climatological wind speed at 10 m height from ERA5 reanalysis dataset [

18] across all the OWF locations.

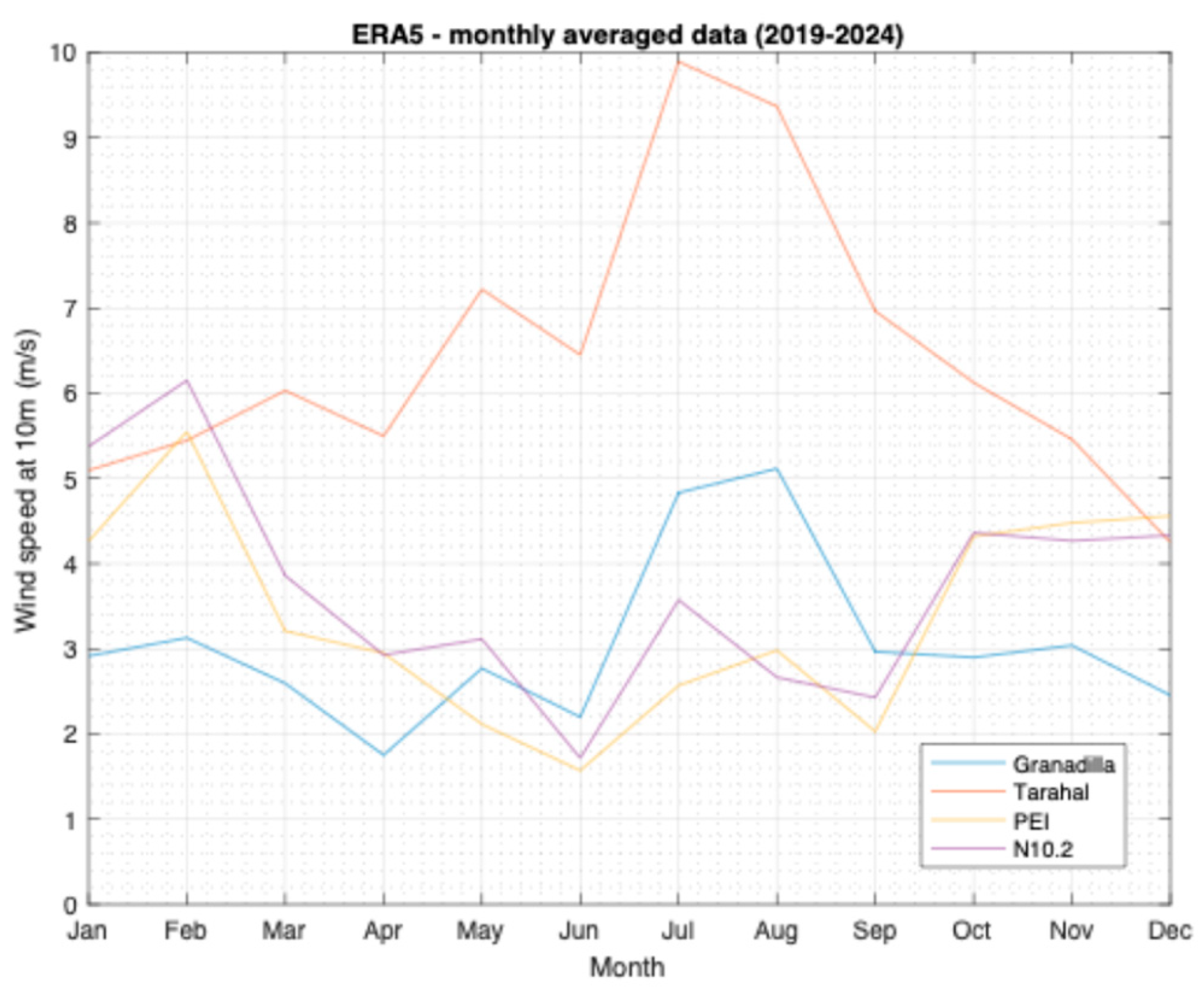

Figure 1 shows the monthly mean wind speed climatology for 2019-2024 for each OWF placement.

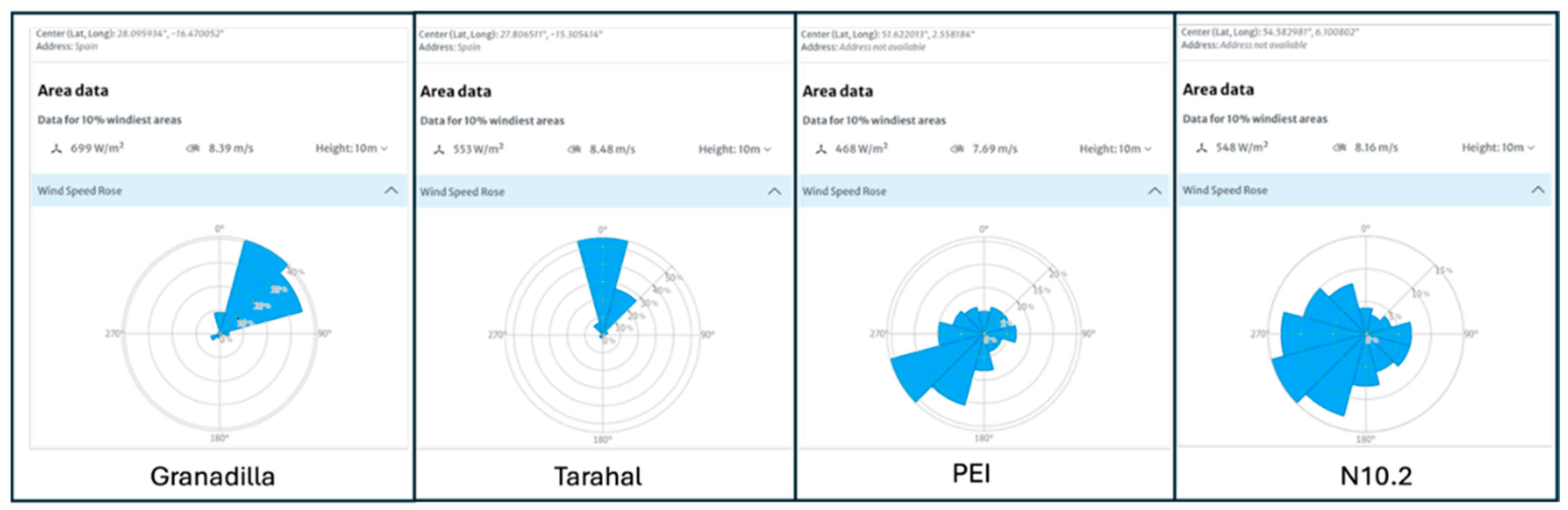

We contrast this 10 m/s threshold with the Global Wind Atlas [

19], confirming that it is a conservative value on each of the OWF sites (

Figure 2).

Source Locations

We define turbine locations, based on defined potential placements found in publicly available sources, for Canary (Spain), Belgium, and German waters.

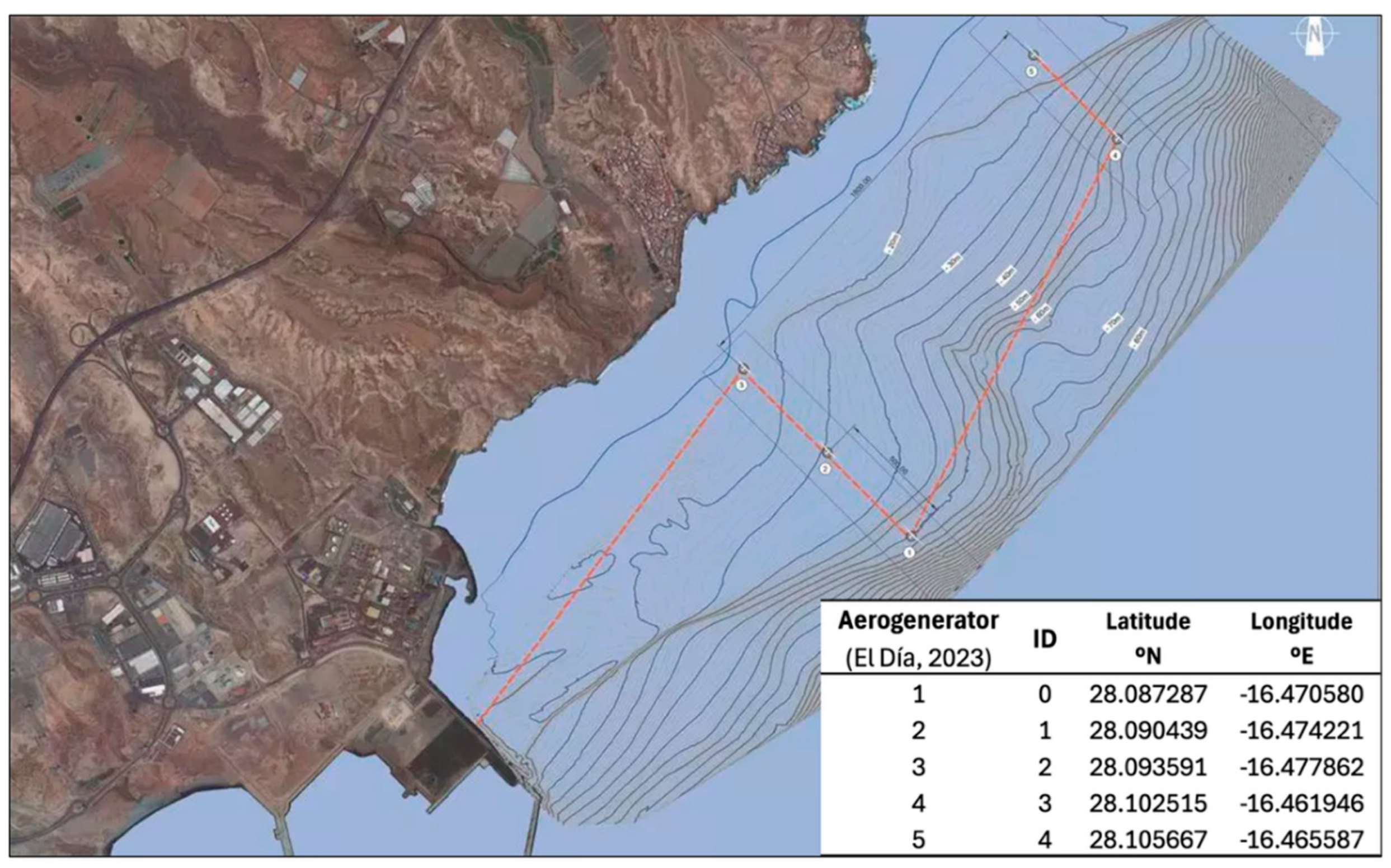

Figure 3 shows the

Granadilla OWF turbines’ localization, from the draft layout of the Granadilla project [

6]. The site is located approximately 2 km north-east of Granadilla port (Tenerife, Spain). The planned turbines at this location are expected to be fixed monopile structures.

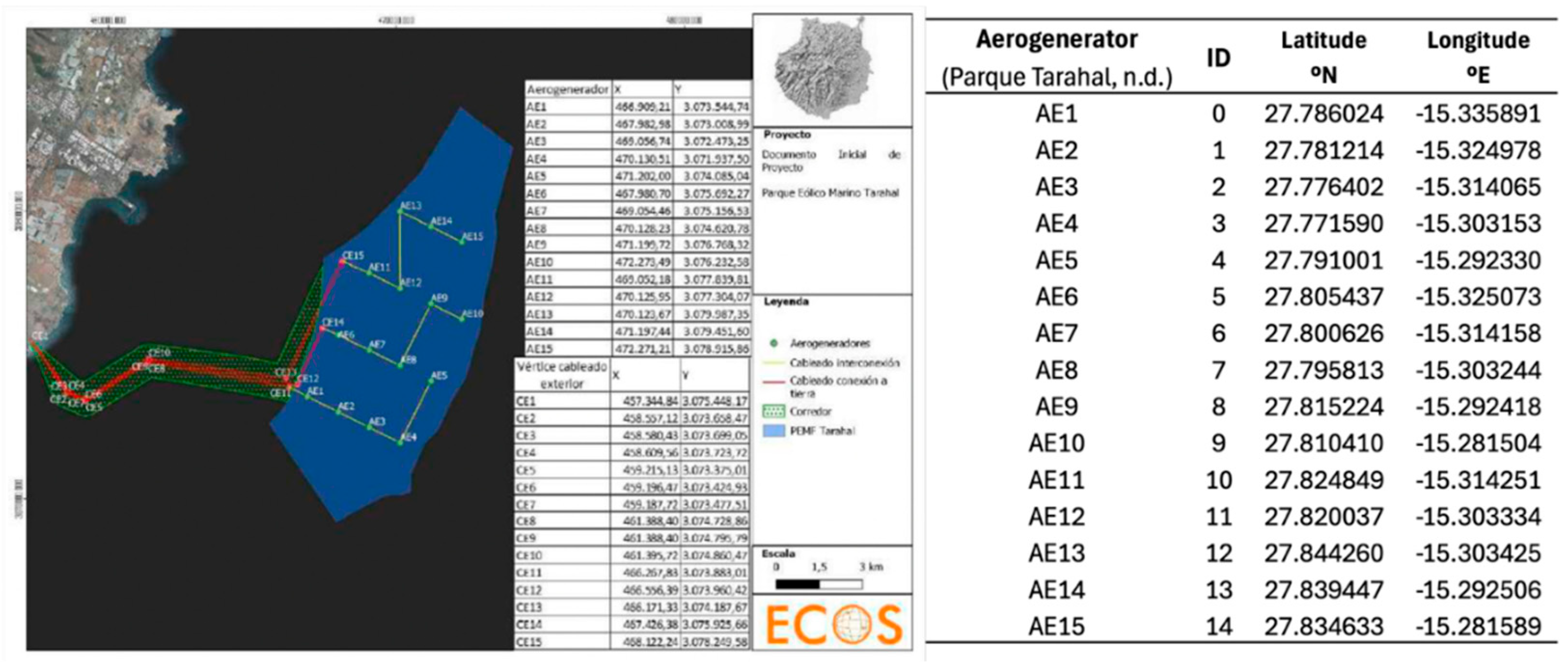

Figure 4 shows the locations of the

Tarahal OWF turbines [

7]. This OWF is planned to be approximately 10 km southeast of the Arinaga coast (Gran Canaria, Spain) and will feature floating turbines.

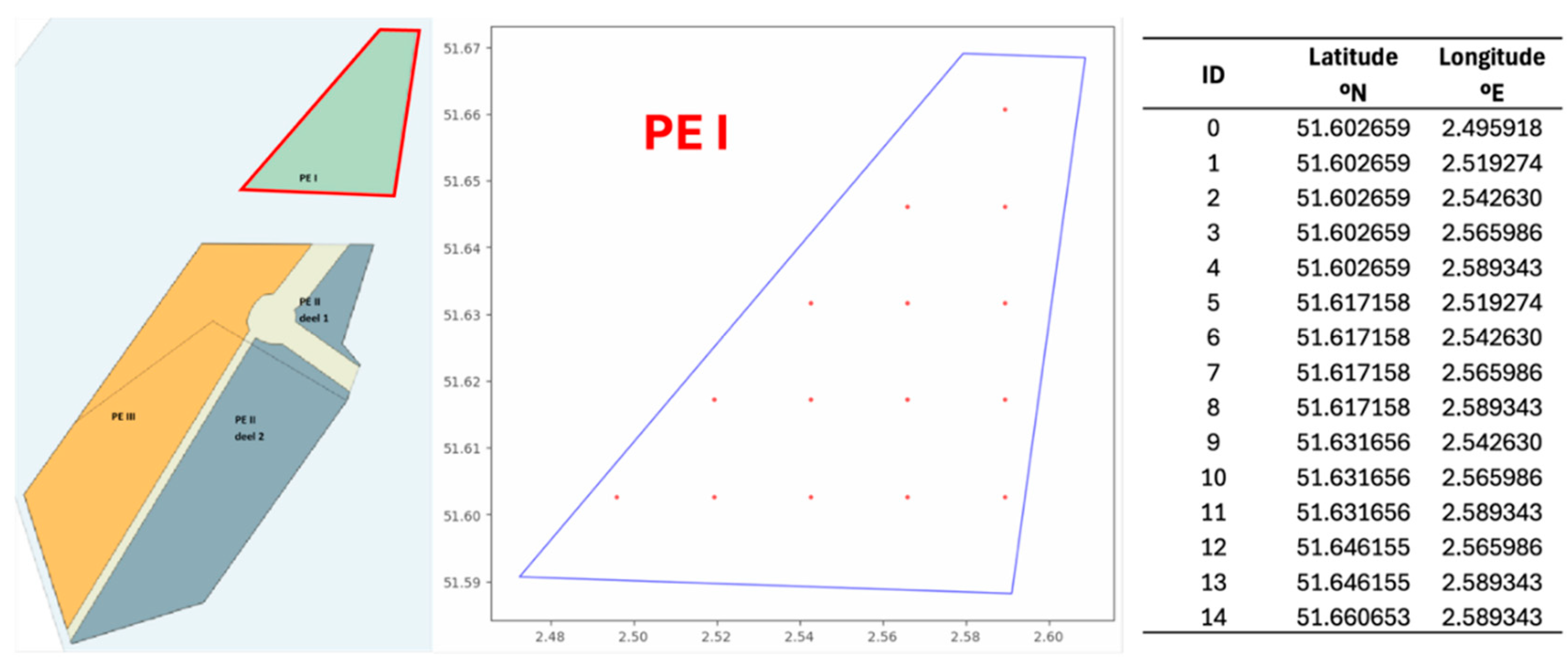

We selected the

Princess Elisabeth Zone I (PEI) for the noise propagation analysis as it represents the furthest stage of development within Belgium’s offshore wind expansion plans [

20]. Although the tender has been postponed until 2026, it remains the most advanced site under preparation, with a defined project area of 46 km² and a planned capacity of 700 MW. Since no preliminary draft of turbine positions is yet available, we assumed a layout with turbine locations separated by one mile in both longitude and latitude within the Princess Elisabeth Zone I (see

Figure 5).

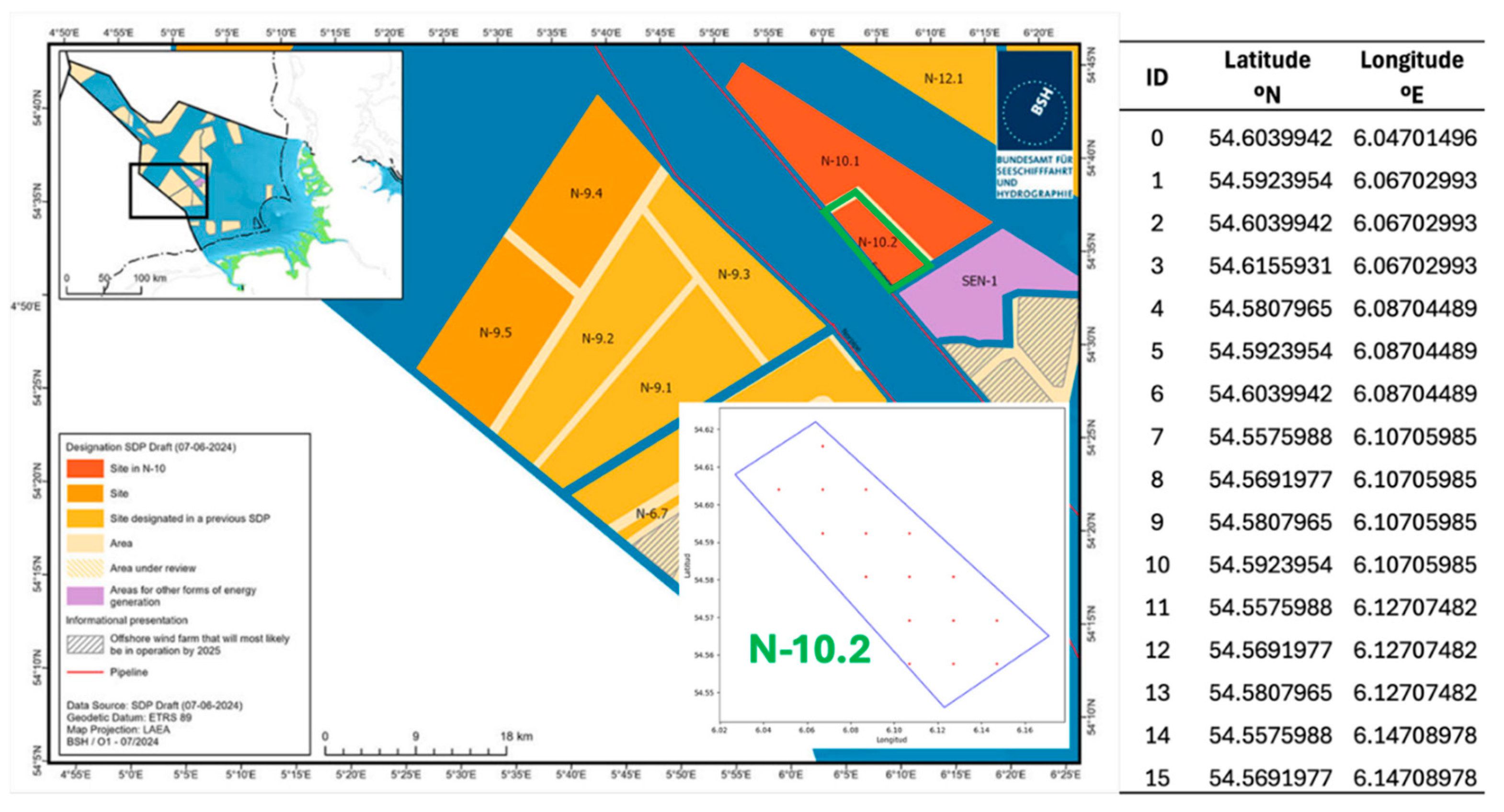

We have selected the German offshore wind development area

N-10.2 for the noise propagation analysis as it is among the most recently designated sites deemed suitable for construction and operation by the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) [

9]. The area covers 31 km², is planned for an installed capacity of 500 MW, and is included in the upcoming 2025 tender, making it a clearly defined and advanced candidate for development. Since no preliminary draft of turbine positions is yet available, we assumed a layout with turbine locations separated by 0.5 miles in both longitude and latitude within the N-10.2 site.

Figure 6.

(Left) Location map of the N-10.2 area for offshore energy within the North Sea Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), from Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH). (Center, inset) Zoomed-in layout showing the assumed turbine locations within N-10.2. (Right) Table with the geographical coordinates of the turbines.

Figure 6.

(Left) Location map of the N-10.2 area for offshore energy within the North Sea Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), from Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH). (Center, inset) Zoomed-in layout showing the assumed turbine locations within N-10.2. (Right) Table with the geographical coordinates of the turbines.

Receiver Locations

Receiver locations representing vulnerable marine zones are selected using spatial data from NATURA 2000 [

21], focusing on areas protected under the Habitats Directive. Additionally, other sensitive areas from IDE Canarias (GRAFCAN) were chosen, catalogued as

Reservas de la Biosfera (BIO) [

22]. Finally, a receiver positioned at the center of the OWF turbines is estimated and denoted as INX (e.g., ING = INside Granadilla).

Table 2 represents the receiver locations adopted to study the potential impact of each OWF on these sites. When land obstructed the path between a source and a receiver, we adjusted the receiver location to the nearest open-water area without interference, and they are described indicated with an *

Bathymetry

Bathymetric information is retrieved from EMODnet [

11]. We have integrated a tool to automatically download the required bathymetric subset based on the defined source and receiver coordinates. This tool interacts with the EMODnet ERDDAP server to select and temporarily download the relevant longitude, latitude, and depth data in .csv format.

For example, in a case where the area of interest spans latitudes from 27° to 28°N and longitudes from −15° to −14°E, the tool generates the following URL, which directly downloads the corresponding .csv file:

By visiting this URL, the dataset is automatically downloaded in the .csv format, allowing its integration into the acoustic model workflow.

Sound speed profile

The sound speed profile (SSP) is estimated as [

12]:

Where c is the underwater sound speed (m/s), T is the temperature (ºC), S is the salinity, and z is the depth (m). We downloaded temperature and salinity data from Copernicus Marine Service, relative to 2020/07/01 [

23].

Bottom Geo-Acoustic Characteristics

In the model setup, a single sediment layer has been assumed. The geoacoustic characteristics of seabed sediments are summarized in [

24]. These results are schematized in [

25] for various common seabed materials, as seen in

Table 3.

Assumptions

We have adopted a conservative, worst-case scenario throughout our analysis. We assume that all turbines operate simultaneously at the same wind speed. We did not consider shadowing effects generated by turbine structures. We applied a single sediment layer with uniform geoacoustic characteristics across the study area. We modeled a basalt seafloor for Granadilla and Tarahal OWF-s and clay for Princess Elisabeth I (PEI) and N-10.2 (N10.2), based on literature and selecting the most conservative values.

In cases where temperature and salinity profiles did not extend to the seafloor, we extrapolated the sound speed profile using the deepest available data point. Frequencies above 500 Hz were excluded due to limitations in the prediction model. We assumed spherical spreading to convert the 50-meter SPL prediction to SL. We validated this assumption by comparing it with RAM-based back-propagation, which showed only minor differences and confirmed our approach as conservative.

We modeled all sound sources at a depth of 10 meters below the sea surface. We used the same real spectrum from a turbine noise operating at 10 m/s wind speed [

3] without distinguishing between floating and fixed turbines, which we consider a conservative choice for frequencies above 20 Hz. Receiver locations were chosen within ZEC and BIO zones; when land obstructed the path between a source and a receiver, we adjusted the receiver location to the nearest open-water area without interference.

3. Results

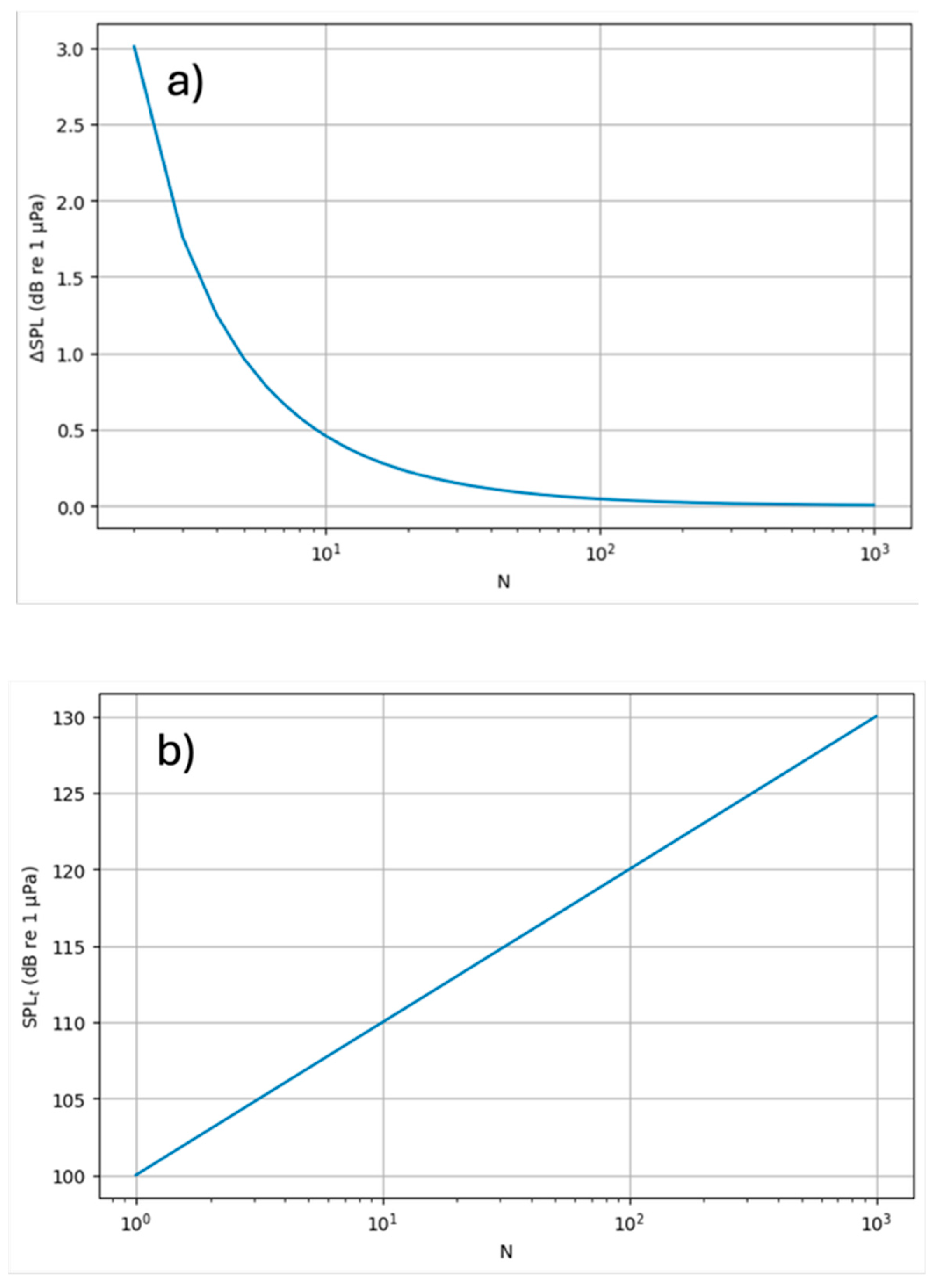

Theoretical Effect of an Additional Noise Source

Before starting with the OWF noise analysis, we first examine the cumulative effect of several identical sources, each with the same SPL (SPL0). Specifically, we are interested in the incremental contribution ΔSPL(N) of the N-th additional source compared to the cumulative SPL from N−1 sources.

Starting from

Equation 2, and assuming SPL

i= SPL

0, we obtain:

Therefore, the incremental contribution of the N-th source is:

This result shows that the additional contribution of each new source (from N=2 onward) is

independent of the absolute SPL0 of a single source, and decreases monotonically as N increases.

Figure 7a illustrates ΔSPL(N) as a function of N. The trend highlights that the relative effect of each new turbine diminishes rapidly: for instance, once 10 turbines are already present, adding one more increases the overall level by less than 0.5 dB.

Figure 7b shows the cumulative SPL (SPL

t) from N sources of SPL

0 = 100 dB re 1mPa.

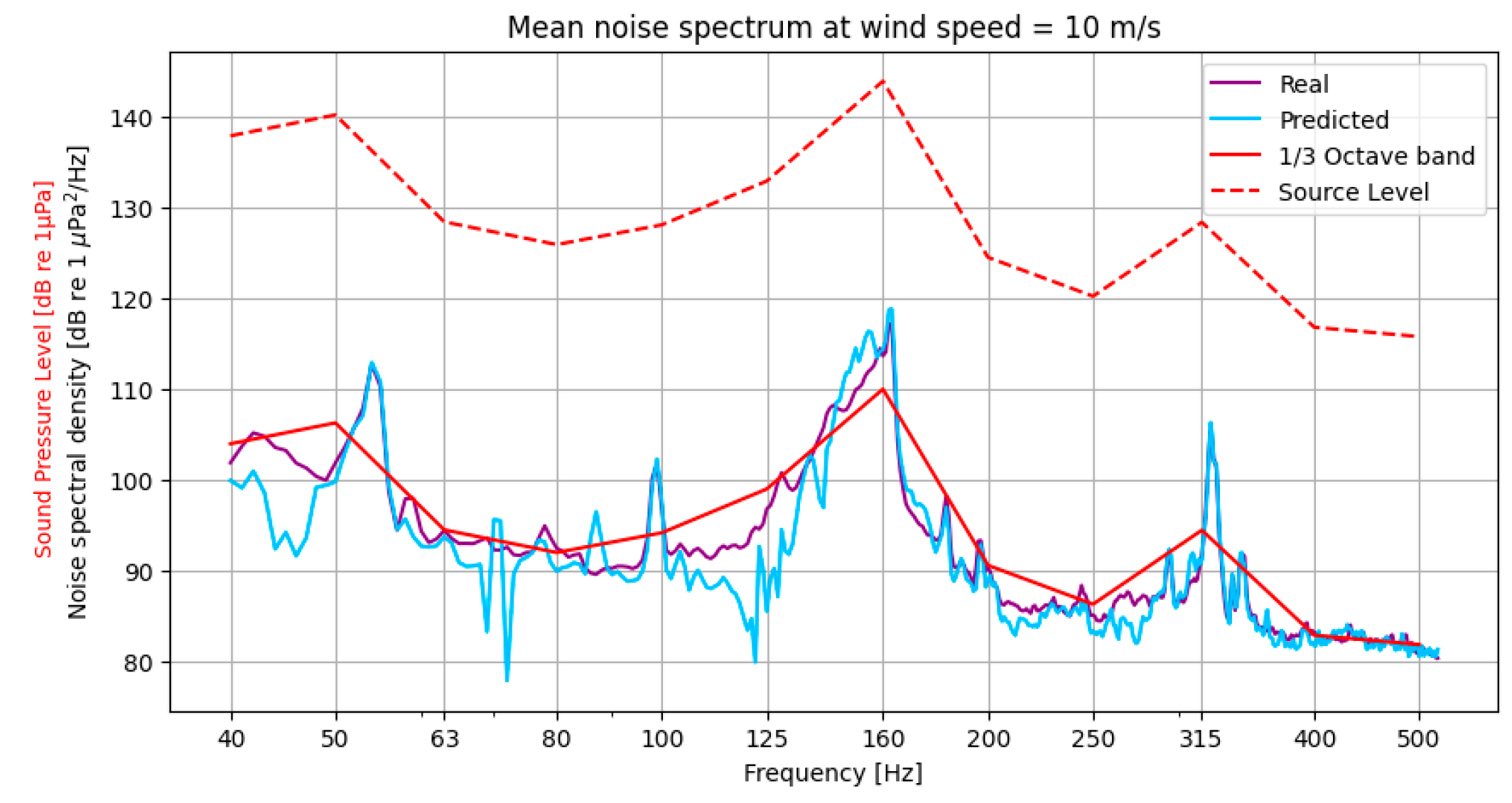

Single Turbine Noise Spectrum

The noise spectra—both measured and predicted—of a single turbine operating at 10 m/s exhibit three peaks at 50, 160, and 315 Hz (

Figure 8). The

real spectrum was used for analysis, as the

predicted spectrum may vary between runs. For computational efficiency, one-third octave bands were back-propagated to the source (50 m), assuming spherical spreading.

In

Figure 8, units differ between representations: noise spectral density is expressed in dB re 1 μPa²/Hz, whereas one-third octave band SPL-s are in dB re 1 μPa. Note that the highest noise occurs at 160 Hz, where the SL reaches 143 dB re 1 μPa.

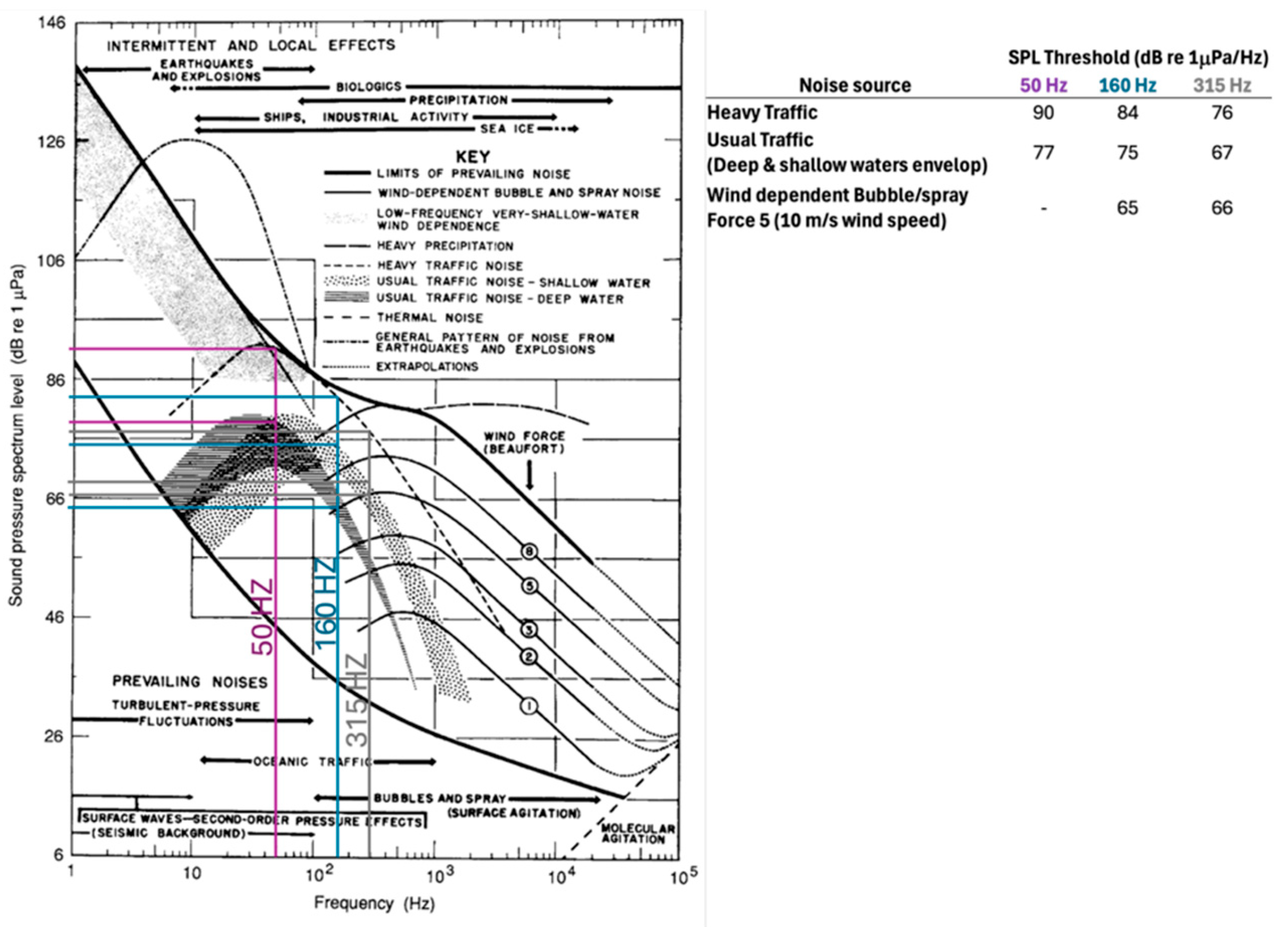

Ambient Noise

We pay special attention to the prevailing frequencies of the turbine noise spectrum (

Figure 8), to later compare with ambient noise curves [

10], and see whether the propagated SPL exceeds the ambient noise at these frequencies. To this effect,

Figure 9 presents the Wenz curves, specifically signaling 50, 160 and 315 Hz frequencies, and a table with estimated values of SPL for each noise source at those frequencies.

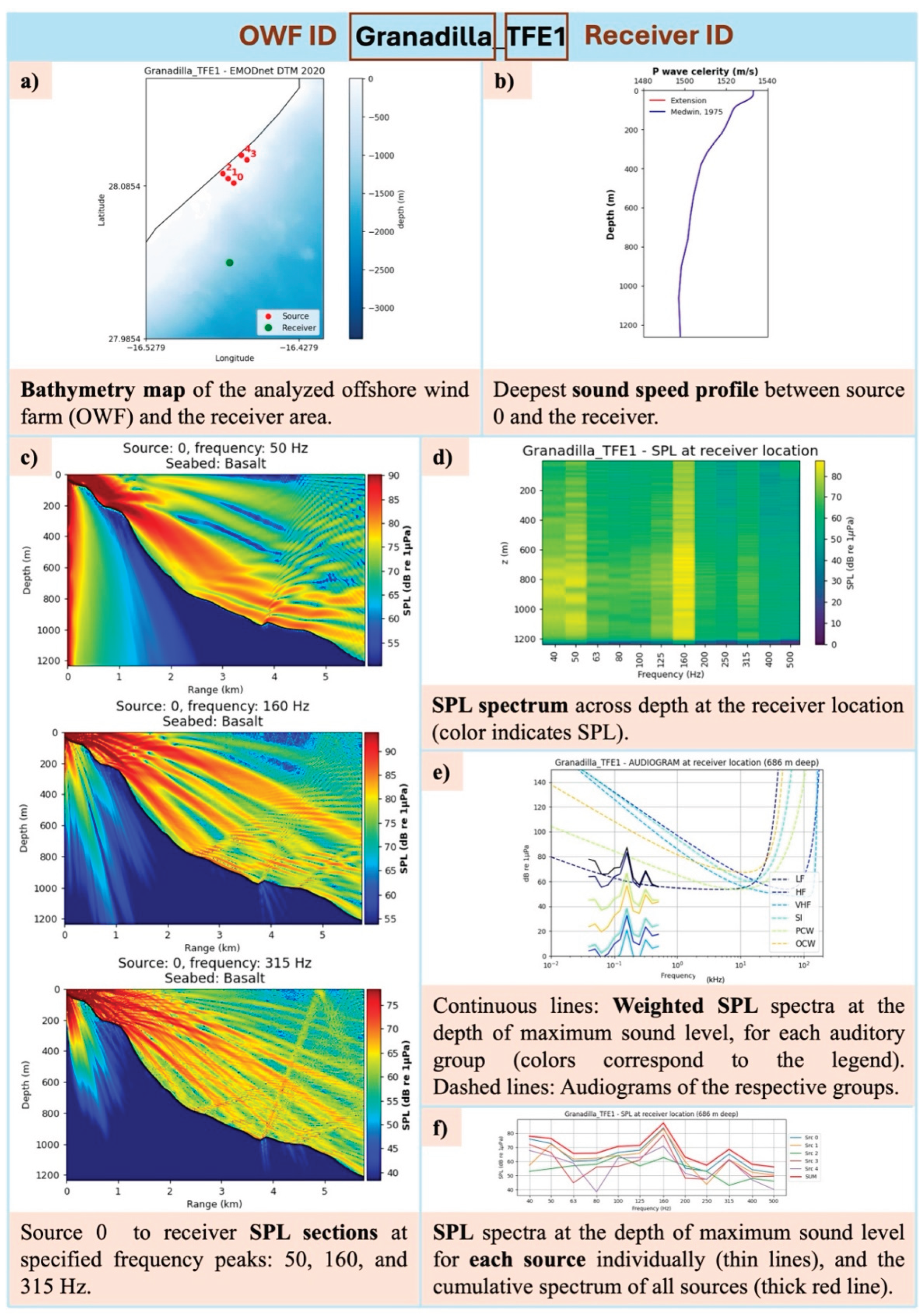

OWF Noise Cumulative Effect Simulation

We present the main outputs from each OWF to each receiver section in the

Supplementary Material. As an example,

Figure 10 provides the description of the outputs obtained with this software.

Key insights from the multiple OWF–receiver analyses (

Supplementary Material) highlight the influence of seabed type and topography on noise transmission, as well as the biological relevance of cumulative sound levels. Basalt seabeds (Granadilla and Tarahal OWFs) exhibit lower transmission losses along the seafloor, with sound reflecting toward the surface, whereas chalk seabeds (PEI and N10.2 OWFs) produce higher losses, particularly at low frequencies (

Supplementary Material, Granadilla_TFE1 and PEI_INP, Panel c). Steep or mountainous seabeds further increase low-frequency transmission losses (

Supplementary Material, PEI_BE, PEI_FR, PEI_NL, Panel c). Regarding biological implications, within OWFs, weighted SPLs exceed audiogram thresholds for both Low-Frequency cetaceans (LF) and Phocid Carnivores in Water (PCW), while outside OWFs only LF species are significantly affected (

Table 3, Thresholds crossed; Supplementary Material, Panel e). Finally, the cumulative effect of multiple turbines compared to a single turbine can raise SPLs by up to 10 dB (N10.2), with the largest contribution consistently coming from the turbine closest to the receiver (

Supplementary Material, Panel f). However, the relative effect of adding further turbines diminishes as their number increases.

We synthesize the most relevant results in

Table 4 to have a broad perspective of the implications of the cumulative effect from the OWF turbines on the different.

From

Table 4, several conclusions emerge regarding noise levels inside (IN

X receivers) and outside OWFs. Inside the farms, cumulative noise at receivers exceeds the reference values for heavy marine traffic across all peak frequencies (50, 160, and 315 Hz), with the highest signal-to-noise ratio of 28 dB at 160 Hz observed in the N10.2_INN section. Outside the farms, SPL attenuation varies with distance depending on bathymetry, sound speed profile, and sediment type: the lowest level (5.51 dB re 1 µPa at 50 Hz) occurs at 44.7 km in the PEI_BE section, while the highest (98.96 dB re 1 µPa at 160 Hz) is found at 7.6 km in the Tarahal_GC4 section. Audiogram comparisons indicate that inside OWFs, weighted spectra exceed hearing thresholds for both Low-Frequency cetaceans (LF) and Phocid Carnivores in Water (PCW), whereas outside, only LF species are significantly affected, as highlighted in the previous section.

Figure 11 presents the SPL of cumulative noise from each OWF, as a range function, for each peak frequency (50, 160, 315 Hz). Note that at 50 Hz, the Transmission losses are generally greater, especially for PEI and N10.2. Both these OWF surrounding waters present shallower and more irregular seafloor. In Granadilla OWF, differently, the SPL is lowest at 315 Hz.

4. Discussion

The propagation of OWF noise varies widely depending on bathymetry, seabed sediment, the water column sound speed profile, and turbines’ geographical distribution. Consequently, the same noise signal can behave very differently in distinct marine environments. This variability aligns with previous findings showing that seabed composition and bathymetry significantly alter low-frequency sound propagation [

26,

27]. Therefore, obtaining accurate estimates of the environmental variables influencing the propagation model is essential to reliably assess potential acoustic impacts. In this study, several assumptions were made to address data gaps, always adopting a conservative approach. The analysis focused on the 40–500 Hz frequency range, where operational wind turbine noise is most relevant and overlaps with the hearing range of several marine mammal groups [

2].

While the theoretical analysis shows that adding turbines with identical source levels (SL) located at the same site leads to diminishing acoustic gains—less than 0.5 dB re 1 µPa beyond approximately ten turbines—this finding should be interpreted in context. Tougaard et al. emphasize that, despite the limited local increase in SPL, the cumulative contribution from the growing number and size of OWFs can become considerable when assessed on a broader spatial scale [

28]. As more turbines are deployed over increasingly large areas, the likelihood that vulnerable species will occur in proximity to at least one turbine also increases. Given that distance is the key factor influencing received SPL, the expansion of OWFs across wider regions effectively enlarges the area exposed to potentially harmful noise levels, thereby amplifying the overall ecological risk.

The main OWF noise at a wind speed of 10 m/s occurs at 160 Hz, centered within the one-third octave band, with operational SL from a single turbine reaching 143 dB in this frequency band. The predicted cumulative noise within the analyzed OWFs surpasses heavy marine traffic noise levels [

10], yielding signal-to-noise ratios of 20–30 dB re 1 µPa at 160 Hz and maximum SPL values of 112 dB re 1 µPa in N10.2_INN. These levels exceed the auditory thresholds of Low-Frequency (LF) Cetaceans and Phocid Carnivores in Water (PCW) [

2], indicating potential threat for such species. However, the actual presence or distribution of these species in the study areas was beyond the scope of this analysis.

Outside the OWFs, SPL decreases with distance from the source, though the decay rate is strongly influenced by bathymetry, sound speed profile, and sediment type. The lowest observed SPL (5.51 dB re 1 µPa at 50 Hz) occurs at 44.7 km in the PEI_BE section, while the highest (98.96 dB re 1 µPa at 160 Hz) is found at 7.6 km in the Tarahal_GC4 section. This spatial variability supports the notion that environmental context critically determines propagation efficiency and, consequently, impact range.

Overall, these findings highlight the complexity of predicting underwater acoustic fields from OWFs and reinforce the need for site-specific, interdisciplinary assessments. Future research should focus on three key areas. First, improved characterization of environmental parameters—such as bathymetry, sediment type, and sound speed profiles—is essential to refine and validate propagation models. Second, more detailed knowledge of species distribution, hearing thresholds, and behavioral sensitivities is needed to accurately assess potential biological impacts. Third, the development of effective mitigation and monitoring strategies should accompany OWF planning and operation to minimize acoustic disturbance. Integrating these components through combined modeling, in situ acoustic measurements, and ecological monitoring will enhance the reliability of impact assessments and support sustainable offshore wind development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the Joint Programming Initiative Healthy and Productive Seas and Oceans (a pan-European intergovernmental platform) through the imPact of soUnd on maRine Ecosystems from offshore WIND energy generation (PURE WIND) Project.

Data Availability Statement

The data and scripts supporting the results of this study are stored on the PURE WIND JupyterHub environment hosted by PLOCAN (

https://jupyterhub.purewind.plocan.eu). Due to server access restrictions, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This article is a publication of the Unidad Océano y Clima from Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, an R&D&I CSIC-associate unit. We gratefully acknowledge the effort of Adrián Vega Morales, hired under the INVESTIGO program for the employment of young people in research and innovation initiatives within the “Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia,” funded by the European Union – “NEXT-GENERATION-EU,” for helping with the integration of models and solving compatibility issues. I thank José Antonio Díaz for granting us access to the PLOCAN Virtual Research Environment (VRE) and for his proactive approach to resolving compatibility issues. I also acknowledge Andrea Trucco for his predisposition and support in integrating his prediction algorithms within the Jupyter notebook used in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OWF |

Offshore Wind Farm |

| SPL |

Sound Pressure Level |

| SL |

Source Level |

| PEI |

Princes Elisabeth I |

| LF |

Low Frequency Cetaceans |

| PCW |

Phocid Carnivores in Water |

References

- Wahlberg, M.; Westerberg, H. Hearing in fish and their reactions to sounds from offshore wind farms. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 288, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southall, B.L.; Finneran, J.J.; Reichmuth, C.; Nachtigall, P.E.; Ketten, D.R.; Bowles, A.E.; Ellison, W.T.; Nowacek, D.P.; Tyack, P.L. Marine mammal noise exposure criteria: Updated scientific recommendations for residual hearing effects. Aquat. Mamm. 2019, 45(2), 125–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucco, A. Predicting underwater noise spectra dominated by wind turbine contributions. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 49(4), 1675–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D. User’s Guide for RAM Versions 1.0 and 1.0p; Naval Research Laboratory: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. Available online: http://oalib.hlsresearch.com/AcousticsToolbox/ (accessed on November 2024).

- Porter, M.B. The BELLHOP Manual and User’s Guide: Preliminary Draft; Heat, Light, and Sound Research, Inc.: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2011. Available online: http://oalib.hlsresearch.com/Rays/HLS-2010-1.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- El Día. El primer parque eólico marino de Tenerife empezará a construirse en 2024. El Día, 13 December 2023. Available online: https://www.eldia.es/tenerife/2023/12/13/primer-parque-eolico-marino-tenerife-95815226.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Parque Tarahal. Documentos del Proyecto. Available online: https://parquetarahal.com/documentos/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Federal Public Service Economy. Identification of the Parcels for the Construction of Wind Farms in the Belgian North Sea. Available online: https://economie.fgov.be/en/themes/energy/sources-and-carriers-energy/offshore/tenders/identification-parcels (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- OffshoreWIND.biz. Germany marks two areas as suitable for 2.5 GW offshore wind. OffshoreWIND.biz, 28 January 2025. Available online: https://www.offshorewind.biz/2025/01/28/germany-marks-two-areas-as-suitable-for-2-5-gw-offshore-wind/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Wenz, G.M. Acoustic ambient noise in the ocean: Spectra and sources. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1962, 34(12), 1936–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry, S.; Dick, S.; George, S.; Benoit, L.; Cyrille, P. EMODnet Bathymetry: A compilation of bathymetric data in the European waters. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2019—Marseille, Marseille, France, 17–20 June 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medwin, H. Speed of sound in water: A simple equation for realistic parameters. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1975, 58(6), 1318–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, M. pyRAM: Python adaptation of the Range-dependent Acoustic Model (RAM). PyPI, 2017. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/pyram/ (accessed on June 2025). (accessed on day month year).

- Porter, M.B. The BELLHOP acoustic ray tracing model. HLS Research, 2005. Available online: http://oalib.hlsresearch.com/AcousticsToolbox/ (accessed on June 2025).

- Chitre, M. Arlpy: Acoustic Research Laboratory Python Library. GitHub, 2020. Available online: https://github.com/org-arl/arlpy/ (accessed on June 2025).

- Copernicus Marine Service. Copernicus Marine Toolbox API – Subset. Copernicus Marine Service, 2024. Available online: https://help.marine.copernicus.eu/en/articles/8283072-copernicus-marine-toolbox-api-subset (accessed on June 2025).

-

EDDAPY: Python client for accessing ERDDAP servers. PyPI, 2023. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/erddapy/ (accessed on June 2025).

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146(730), 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.N.; Badger, J.; Hahmann, A.N.; Hansen, B.O.; Mortensen, N.G.; Kelly, M.; Larsén, X.G.; Olsen, B.T.; Floors, R.; Lizcano, G.; et al. The Global Wind Atlas: A high-resolution dataset of climatologies and associated web-based application. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104(8), E1507–E1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OffshoreWIND.biz. Belgium delays tender for offshore wind farm in Princess Elisabeth Zone until 2026. OffshoreWIND.biz, 1 July 2025. Available online: https://www.offshorewind.biz/2025/07/01/belgium-delays-tender-for-offshore-wind-farm-in-princess-elisabeth-zone-until-2026/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Natura 2000 Data: The European Network of Protected Sites. Available online: https://natura2000.eea.europa.eu/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- GRAFCAN/Gobierno de Canarias. Visor IDECanarias. Available online: https://visor.grafcan.es/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030. Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis. E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS), Marine Data Store (MDS). (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.L. Geoacoustic modeling of the sea floor. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1980, 68(5), 1313–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.B.; Kuperman, W.A.; Porter, M.B.; Schmidt, H. Computational Ocean Acoustics, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Godin, O.A. Underwater sound propagation over a layered seabed with weak shear rigidity. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157(1), 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, X.; Zhang, P.; Feng, Z. Study of underwater sound propagation and attenuation characteristics at the Yangjiang offshore wind farm. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 84, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougaard, J.; Hermannsen, L.; Madsen, P.T. How loud is the underwater noise from operating offshore wind turbines? J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Monthly climatology of 10 m wind speed for each OWF, derived from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset.

Figure 1.

Monthly climatology of 10 m wind speed for each OWF, derived from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset.

Figure 2.

10 m wind speed statistics from the Global Wind Atlas [

19], evaluated at the center of each OWF.

Figure 2.

10 m wind speed statistics from the Global Wind Atlas [

19], evaluated at the center of each OWF.

Figure 3.

Location map of the projected turbines for the Granadilla OWF. The table at the bottom right shows the geographical coordinates of the turbines, with the first column indicating the labels from the project draft and the second column the labels adopted in this study.

Figure 3.

Location map of the projected turbines for the Granadilla OWF. The table at the bottom right shows the geographical coordinates of the turbines, with the first column indicating the labels from the project draft and the second column the labels adopted in this study.

Figure 4.

Location map of the projected turbines for the Tarahal OWF. The table at right shows the geographical coordinates of the turbines, with the first column indicating the labels from the project draft and the second column the labels adopted in this study.

Figure 4.

Location map of the projected turbines for the Tarahal OWF. The table at right shows the geographical coordinates of the turbines, with the first column indicating the labels from the project draft and the second column the labels adopted in this study.

Figure 5.

(Left) Location map of the Princess Elisabeth zones (Federal Public Service Economy, n.d.). (Center) Assumed turbine locations within Princess Elisabeth Zone I (PEI). (Right) Table with the geographical coordinates of the turbines.

Figure 5.

(Left) Location map of the Princess Elisabeth zones (Federal Public Service Economy, n.d.). (Center) Assumed turbine locations within Princess Elisabeth Zone I (PEI). (Right) Table with the geographical coordinates of the turbines.

Figure 7.

(a) Incremental SPL (ΔSPL) of the N-th source, assuming all sources have the same SPL. (b) Cumulative SPL (SPLₜ) obtained by adding N sources, each with an SPL of 100 dB re 1 μPa.

Figure 7.

(a) Incremental SPL (ΔSPL) of the N-th source, assuming all sources have the same SPL. (b) Cumulative SPL (SPLₜ) obtained by adding N sources, each with an SPL of 100 dB re 1 μPa.

Figure 8.

Real (purple) and predicted (blue [

3]) noise spectral density (dB re 1 mPa

2/Hz) from a single turbine located 50 m away, operating at a wind speed of 10 m/s. Red lines indicate the one-third octave band SPL from the real spectrum at 50 m (solid line) and at 1 m from the source (dashed line; source level).

Figure 8.

Real (purple) and predicted (blue [

3]) noise spectral density (dB re 1 mPa

2/Hz) from a single turbine located 50 m away, operating at a wind speed of 10 m/s. Red lines indicate the one-third octave band SPL from the real spectrum at 50 m (solid line) and at 1 m from the source (dashed line; source level).

Figure 9.

(Left) Composite ambient noise spectra adapted from Wenz (1962), highlighting the 50 Hz (purple), 160 Hz (blue), and 315 Hz (grey) frequencies. (Right) Table showing heavy and typical traffic noise, as well as wind-dependent bubble and spray noise (Beaufort Force 5), for each of the 50, 160, and 315 Hz frequencies.

Figure 9.

(Left) Composite ambient noise spectra adapted from Wenz (1962), highlighting the 50 Hz (purple), 160 Hz (blue), and 315 Hz (grey) frequencies. (Right) Table showing heavy and typical traffic noise, as well as wind-dependent bubble and spray noise (Beaufort Force 5), for each of the 50, 160, and 315 Hz frequencies.

Figure 10.

Schematic of the main outputs from each OWF to its respective receiver (OWF ID_Receiver ID). Figures for all sections follow this scheme and are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 10.

Schematic of the main outputs from each OWF to its respective receiver (OWF ID_Receiver ID). Figures for all sections follow this scheme and are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 11.

Maximum SPL from each OWF at the receiver as a function of range for the frequencies 50, 160, and 315 Hz. The horizontal red, brown, and green lines represent heavy traffic noise, usual traffic noise, and wind-dependent bubble and spray noise (sea state 5), respectively, as reported by [

10]. The black line represents the least squares regression line.

Figure 11.

Maximum SPL from each OWF at the receiver as a function of range for the frequencies 50, 160, and 315 Hz. The horizontal red, brown, and green lines represent heavy traffic noise, usual traffic noise, and wind-dependent bubble and spray noise (sea state 5), respectively, as reported by [

10]. The black line represents the least squares regression line.

Table 1.

Proposed marine mammal hearing groups and example species or genera within each group, as defined by [

2].

Table 1.

Proposed marine mammal hearing groups and example species or genera within each group, as defined by [

2].

| Marine mammal hearing group |

ID |

Genera (or species) included |

| Low-frequency cetaceans |

LF |

Balaenidae (Balaena, Eubalaena spp.); Balaenopteridae (Balaenoptera physalus, B. musculus)

Balaenopteridae (Balaenoptera acutorostrata, B. bonaerensis, B. borealis, B. edeni, B. omurai; Megaptera novaeangliae); Neobalaenidae (Caperea); Eschrichtiidae (Eschrichtius) |

| High-frequency cetaceans |

HF |

Physeteridae (Physeter); Ziphiidae (Berardius spp., Hyperoodon spp., Indopacetus, Mesoplodon spp., Tasmacetus, Ziphius); Delphinidae (OrcinusDelphinus, Feresa, Globicephala spp., Grampus, Lagenodelphis, Lagenorhynchus acutus, L. albirostris, L. obliquidens, L. obscurus, Lissodelphis spp., Orcaella spp., Peponocephala, Pseudorca, Sotalia spp., Sousa spp., Stenella spp., Steno, Tursiops spp); Montodontidae (Delphinapterus, Monodon); Plantanistidae (Plantanista) |

| Very high-frequency cetaceans |

VHF |

Delphinidae (Cephalorhynchus spp.; Lagenorhynchus cruciger, L. australis); Phocoenidae (Neophocaena spp., Phocoena spp., Phocoenoides); Iniidae (Inia); Kogiidae (Kogia); Lipotidae (Lipotidae); Pontoporiidae (Pontoporia) |

| Sirenians |

SI |

Trichechidae (Trichechus spp.); Dugongidae (Dugong) |

| Phocid carnivores in water |

PCW |

Phocidae (Cystophora, Erignathus, Halichoerus, Histriophoca, Hydrurga, Leptonychotes, Lobodon, Mirounga spp., Monachus, Neomonachus, Ommatophoca, Pagophilus, Phoca spp., Pusa spp.) |

| Other marine carnivores in water |

OCW |

Odobenidae (Odobenus); Otariidae (Arctocephalus californicus, Callorhinus, Eumetopias, Neophoca, Otaria, Phocarctos, Zalophus spp.); Ursidae (Ursus maritimus); Mustelidae (Enhydra, Lontra felina) |

Table 2.

Receiver locations adopted in this study for OWF noise propagation analysis.

Table 2.

Receiver locations adopted in this study for OWF noise propagation analysis.

| OWF |

ID |

Description |

Latitude

ºN |

Longitude

ºE |

| Granadilla |

ING |

Inside OWF |

28.095000 |

-16.465587 |

| TFE1 |

Natura 2000

Sebadales del sur de Tenerife (ES7020116)* |

28.035364 |

-16.473202 |

| TFE2 |

BIO* |

28.446869 |

-16.104856 |

| GC1 |

Natura 2000

Franja marina de Mogán (ES7010017) |

27.902083 |

-15.889972 |

| Tarahal |

INT |

Inside OWF |

27.807925 |

-15.303244 |

| GC2 |

Natura 2000

Franja marina de Mogán (ES7010017) |

27.705500 |

-15.597093 |

| GC3 |

Natura 2000

Sebadales de Playa del Inglés (ES7010056) |

27.750467 |

-15.541356 |

| GC4 |

Natura 2000

Playa del Cabrón (ES7010053) |

27.835319 |

-15.370708 |

| FTV1 |

Natura 2000

Espacio marino del oriente y sur de Lanzarote-Fuerteventura (ESZZ15002) |

28.043689 |

-14.526958 |

| FTV2 |

28.041669 |

-14.316244 |

| PEI |

INP |

Inside OWF |

51.6219905 |

2.55820093 |

| BE |

Natura 2000

Vlaamse Banken (BEMNZ0001) |

51.226348 |

2.665838 |

| FR |

Natura 2000

Récifs Gris-Nez Blanc-Nez (FR3102003) |

50.953812 |

1.499381 |

| NL |

Natura 2000

Voordelta (NL4000017) |

51.576599 |

3.398938 |

| N10.2 |

INN |

Inside OWF |

54.582971 |

6.100805 |

| DE1 |

Natura 2000

Borkum-Riffgrund (DE2104301) |

53.855072 |

6.368749 |

| DE2 |

Natura 2000

Sylter Außenriff (DE1209301) |

54.797312 |

7.303316 |

| NL2 |

Natura 2000

Doggersbank (NL2008001) |

55.223200 |

3.767259 |

| NL3 |

Natura 2000

Klaverbank (NL2008002) |

54.014082 |

3.088145 |

Table 3.

Geoacoustic properties of continental shelf and slope environments [

23,

24].

Table 3.

Geoacoustic properties of continental shelf and slope environments [

23,

24].

| Bottom Type |

rb/rw

|

cp/cw

|

αp (dB/λp) |

| Clay |

1.5 |

1.00 |

0.2 |

| Silt |

1.7 |

1.05 |

0.3 |

| Sand |

1.9 |

1.10 |

0.8 |

| Gravel |

2.0 |

1.20 |

0.6 |

| Moraine |

2.1 |

1.30 |

0.8 |

| Chalk |

2.2 |

1.60 |

0.2 |

| Limestone |

2.4 |

1.80 |

0.4 |

| Basalt |

2.7 |

3.50 |

0.1 |

Table 4.

Summary of propagation model outputs for each OWF at each receiver. Column 1 lists the OWF ID and number of turbines; Column 2 lists the receiver ID. Avg range indicates the average distance between OWF turbines and the receiver. Max depth is the maximum bathymetric depth along the path from turbines to receiver, while Rec depth denotes the bathymetric depth at the receiver. Max SPL depth is the depth where the cumulative SPL spectrum is most intense at the receiver. Max SPL represents the cumulative SPL from all turbines at each peak frequency at the receiver location and max SPL depth. Red, brown, and green values indicate levels exceeding heavy traffic, usual traffic, and wind-dependent bubble/spray ambient noise, respectively. Thresholds crossed indicate the auditory groups predicted to be affected by cumulative OWF noise at each receiver location and corresponding max SPL depth.

Table 4.

Summary of propagation model outputs for each OWF at each receiver. Column 1 lists the OWF ID and number of turbines; Column 2 lists the receiver ID. Avg range indicates the average distance between OWF turbines and the receiver. Max depth is the maximum bathymetric depth along the path from turbines to receiver, while Rec depth denotes the bathymetric depth at the receiver. Max SPL depth is the depth where the cumulative SPL spectrum is most intense at the receiver. Max SPL represents the cumulative SPL from all turbines at each peak frequency at the receiver location and max SPL depth. Red, brown, and green values indicate levels exceeding heavy traffic, usual traffic, and wind-dependent bubble/spray ambient noise, respectively. Thresholds crossed indicate the auditory groups predicted to be affected by cumulative OWF noise at each receiver location and corresponding max SPL depth.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

máx SPL (dB re 1uPa) |

|

OWF ID

(# turbines)

|

Receiver ID |

avg range (km) |

máx depth (m) |

rec depth (m) |

máx SPL depth (m) |

50Hz |

160 Hz |

315 Hz |

Thresholds crossed |

Granadilla

5 |

ING |

1.05 |

46.4 |

46.2 |

26 |

101.08 |

109.16 |

90.77 |

LF / PCW |

| TFE1 |

6.73 |

1211.6 |

1211.6 |

686 |

76.21 |

87.24 |

68.60 |

LF |

| TFE2 |

52.88 |

2159.6 |

2159.6 |

1614 |

58.97 |

65.33 |

44.15 |

LF |

| GC1 |

60.97 |

2539.8 |

87.6 |

56 |

70.62 |

74.35 |

56.24 |

LF |

Tarahal

15 |

INT |

2.71 |

500.2 |

322.2 |

60 |

96.93 |

102.43 |

82.32 |

LF / PCW |

| GC2 |

30.92 |

500.2 |

59.2 |

38 |

71.39 |

83.99 |

64.65 |

LF |

| GC3 |

24.16 |

500.2 |

31.2 |

28 |

77.04 |

86.48 |

66.68 |

LF |

| GC4 |

7.64 |

500.2 |

54.4 |

4 |

81.58 |

98.96 |

77.97 |

LF |

| FTV1 |

81.04 |

2008.2 |

28.4 |

26 |

81.72 |

78.21 |

62.06 |

LF |

| FTV2 |

100.82 |

2046.4 |

65.8 |

12 |

60.38 |

57.51 |

40.38 |

LF |

PEI

15 |

INP |

2.6 |

38.88 |

33.1 |

9 |

104.51 |

109.65 |

91.80 |

LF / PCW |

| BE |

44.70 |

40.17 |

12.45 |

7 |

5.51 |

79.21 |

68.33 |

LF |

| FR |

104.80 |

60.1 |

49.45 |

16 |

23.04 |

62.86 |

43.41 |

- |

| NL |

49.73 |

68.79 |

15.97 |

11 |

59.49 |

80.56 |

65.23 |

LF |

N10.2

16 |

INN |

2.48 |

41.54 |

40.57 |

39 |

107.20 |

112.15 |

96.04 |

LF / PCW |

| DE1 |

82.90 |

41.54 |

25.68 |

15 |

63.65 |

80.56 |

65.33 |

LF |

| DE2 |

81.16 |

41.53 |

24.2 |

16 |

65.33 |

81.44 |

64.47 |

LF |

| NL2 |

165.79 |

48.47 |

39.15 |

30 |

52.64 |

71.84 |

58.72 |

LF |

| NL3 |

206.10 |

49.3 |

38.08 |

29 |

44.19 |

67.66 |

53.27 |

LF |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).