Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

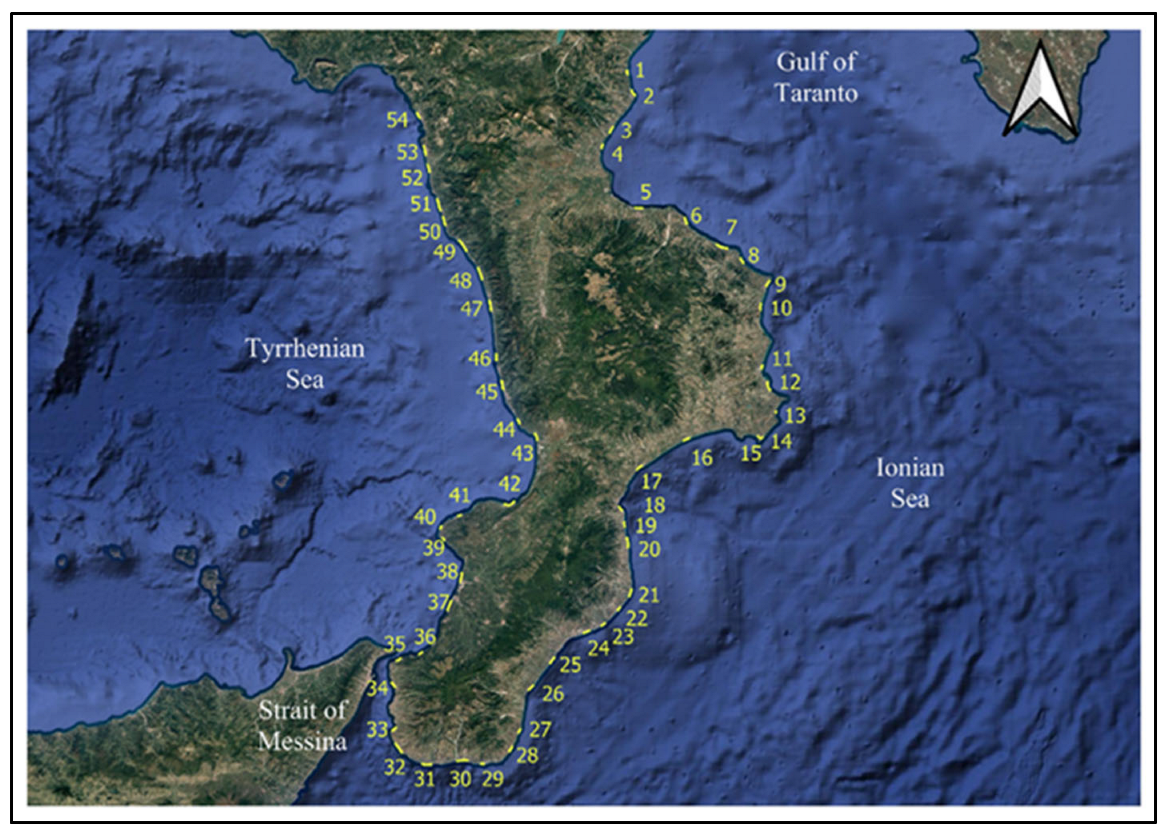

2.1. Case Study: The Calabria Region

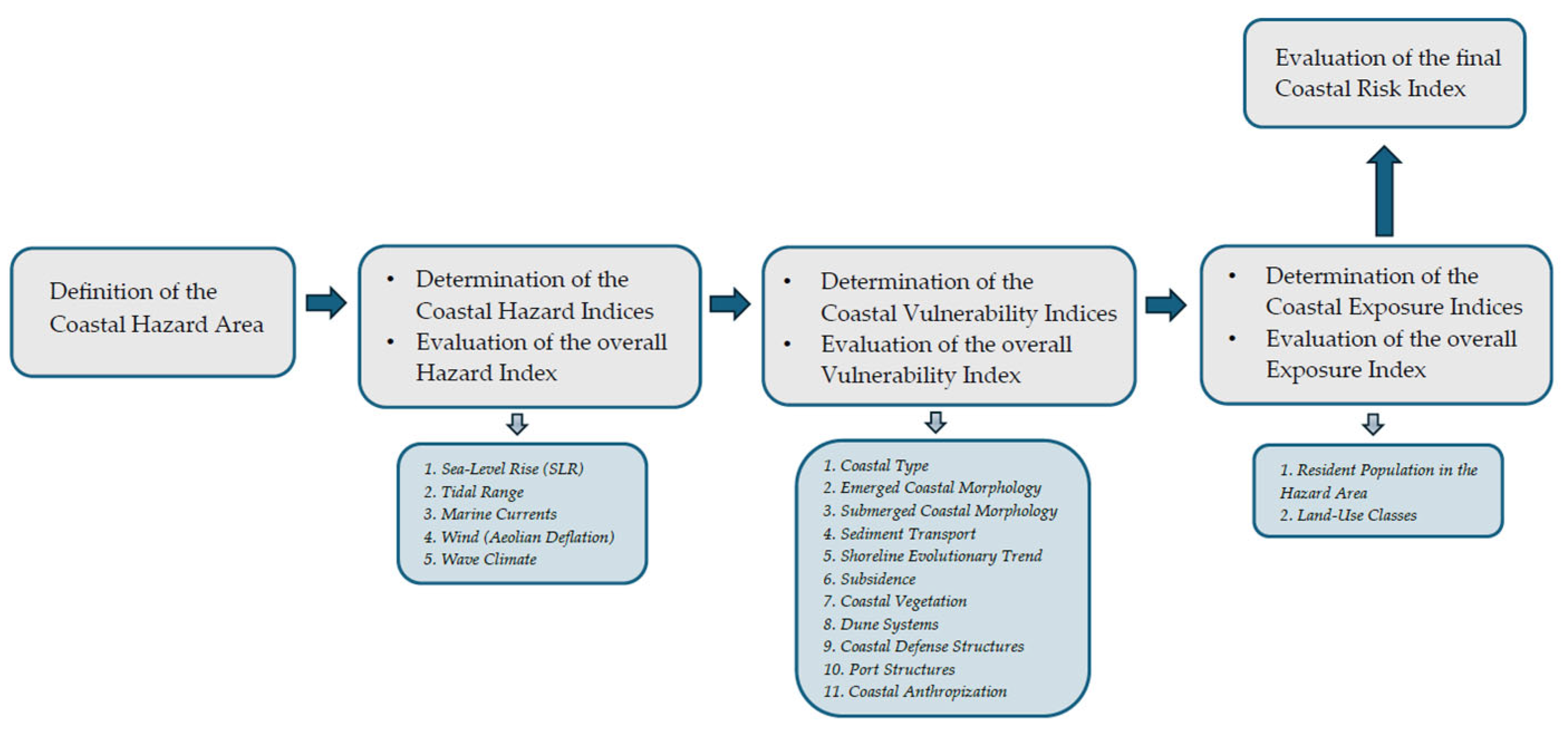

2.2. Methodological Framework

- Determination of the Coastal Hazard Indices and evaluation of the overall hazard index;

- Determination of the Coastal Vulnerability Indices and evaluation of the overall vulnerability index;

- Determination of the Coastal Exposure Indices and evaluation of the overall exposure index;

- Evaluation of the final Coastal Risk Index.

2.2.1. Definition of the Coastal Hazard Area

- Wave run-up and set-up (with a return period of 100 years);

- Astronomical and meteorological tides;

- Projected sea-level rise over a 100-year horizon according to the most severe IPCC scenario.

2.2.2. Hazard Indices

2.2.3. Coastal Vulnerability Indices

- if the structure is an emerged barrier, the PSL is assumed to be equal to the length of the barrier itself;

- if the structure is a submerged barrier, the PSL is estimated as the length of the barrier multiplied by a coefficient corresponding to the wave transmission coefficient of the structure, calculated in this study using the empirical formulation proposed by Van der Meer (1990) [69].

- If the structure in question is a groyne, the corresponding PSL is evaluated based on both its length and the angle of incidence of the predominant wave direction.

- In the case of a T-head groyne, that is a combination of a groyne and a breakwater, the PSL is calculated as the sum of the contributions attributed to the breakwater and the groyne components.

2.2.4. Coastal Exposure Indices

2.2.5. Coastal Risk Index

3. Results

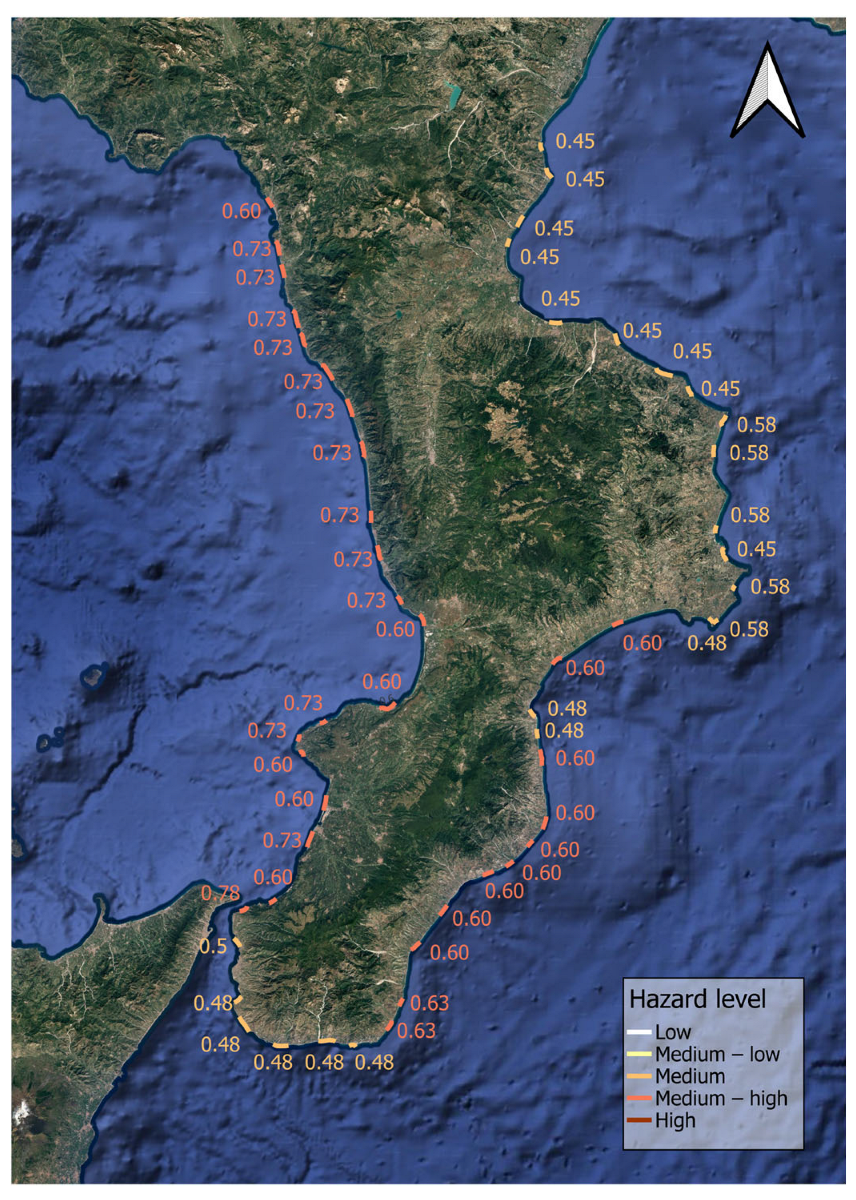

3.1. Coastal Hazard

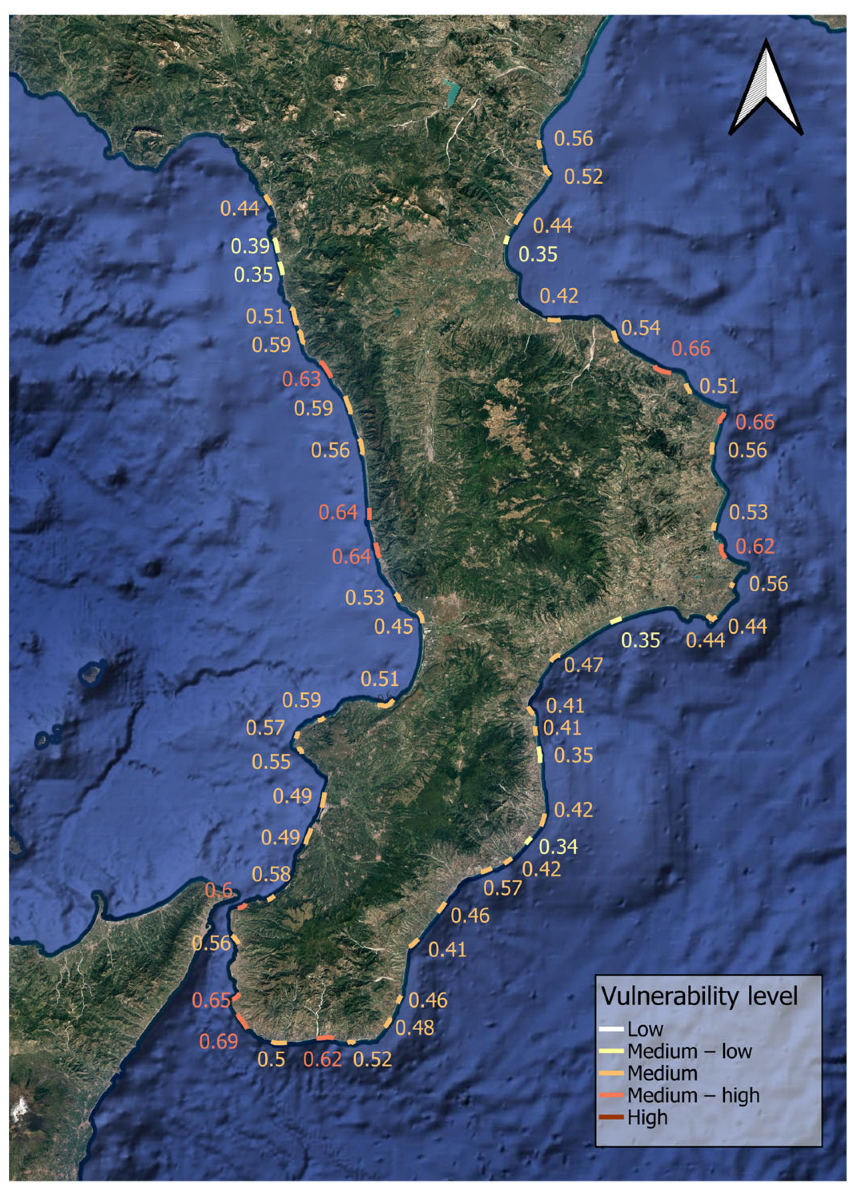

3.2. Coastal Vulnerability

3.3. Coastal Hazard-Area

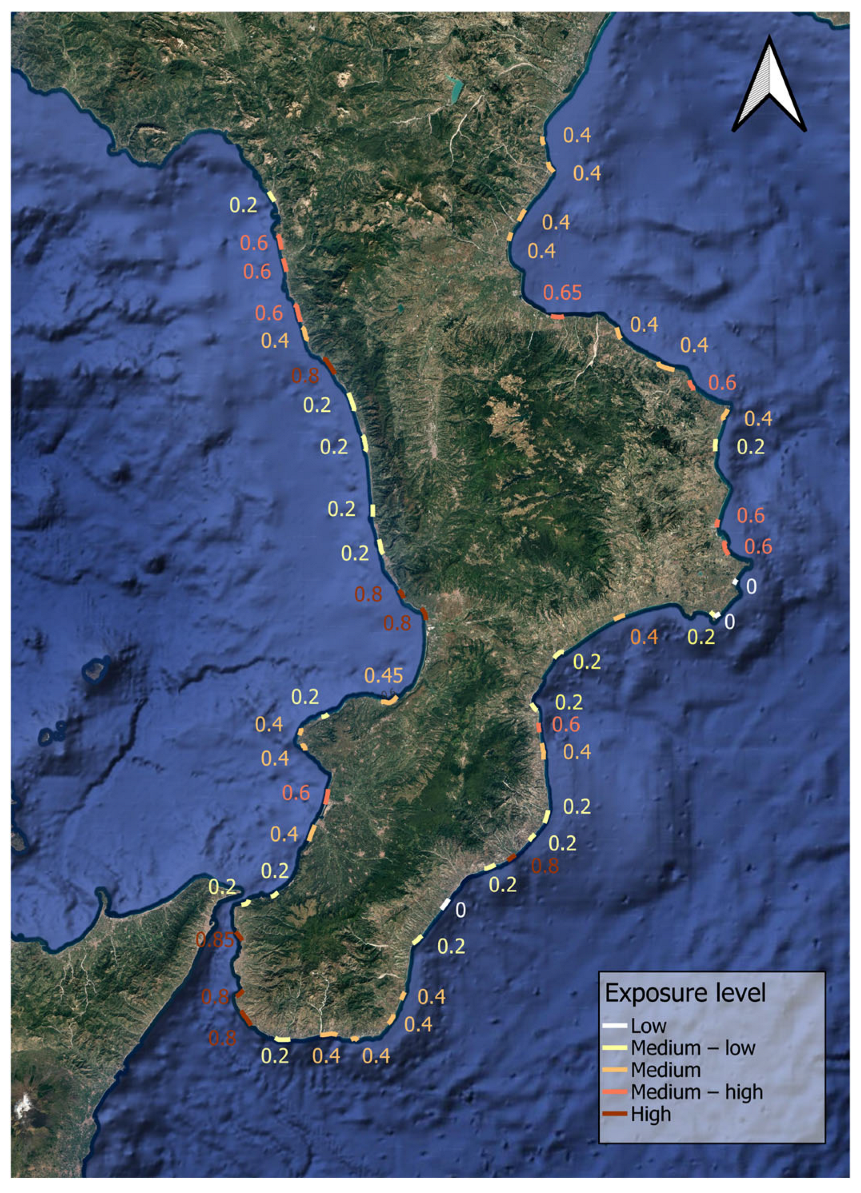

3.4. Coastal Exposure

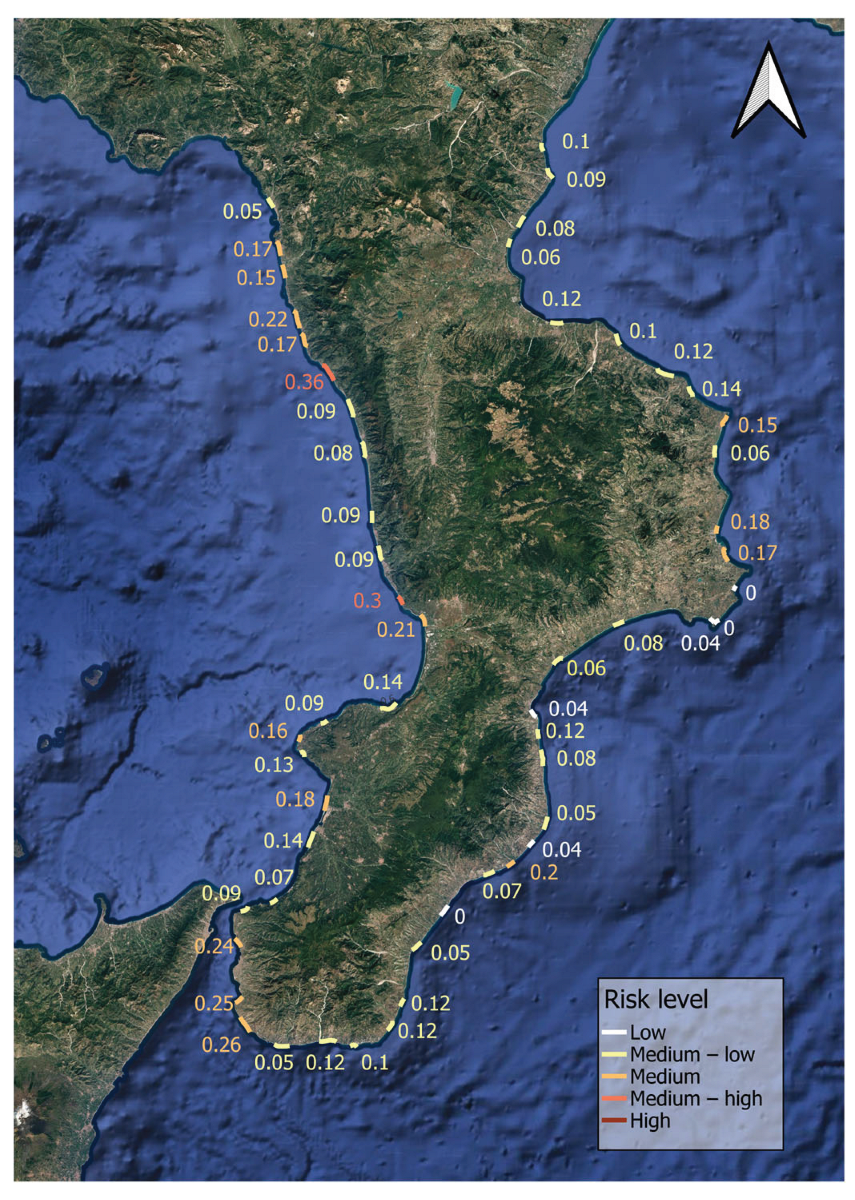

3.5. Coastal Risk

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLaughlin, S.; Cooper, J.A.G. A multi-scale coastal vulnerability index: A tool for coastal managers? Environ. Hazards 2010, 9, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramieri, E.; Hartley, A.; Barbanti, A.; Santos, F.D.; Gomes, A.; Hilden, M.; Santini, M. Methods for assessing coastal vulnerability to climate change. ETC CCA Tech. Pap. 2011, 1, 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- Komar, P.D. Coastal erosion–underlying factors and human impacts. Shore & Beach 2000, 68, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro, G.; Foti, G.; Sicilia, C.L. Coastal erosion in the South of Italy. Disaster Adv. 2014, 7, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Ranasinghe, R.; Mentaschi, L.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Athanasiou, P.; Luijendijk, A.; Feyen, L. Sandy coastlines under threat of erosion. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães Filho, L.N.L.; Roebeling, P.C.; Costa, L.F.C.; Lima, L.T. Ecosystem services values at risk in the Atlantic coastal zone due to sea-level rise and socioeconomic development. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 58, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, O.; Chatzipavlis, A.; Hasiotis, T.; Monioudi, I.; Manoutsoglou, E.; Velegrakis, A. Assessment of and adaptation to beach erosion in islands: An integrated approach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.Y.; Díaz, L.J.O.; Cueto, J.E. Assessment and management of coastal erosion in the marine protected area of the Rosario Island archipelago (Colombian Caribbean). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V. Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Glob. Planet. Change 1991, 3, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieler, E.R.; Hammar-Klose, E. National Assessment of Coastal Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise: Preliminary Results for the U.S. Atlantic Coast. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 99-593; U.S. Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Viavattene, C.; Jiménez, J. A.; Ferreira, O.; Priest, S.; Owen, D.; McCall, R. Finding coastal hotspots of risk at the regional scale: the Coastal Risk Assessment Framework. Coast. Eng. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, A.; Snoussi, M.; Puddu, M.; Flayou, L.; Hoult, R. An index-based method to assess risks of climate-related hazards in coastal zones: the case of Tetouan. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 175, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, A.; Puddu, M.; Venturini, S.; Giupponi, C. Assessment of coastal risks to climate change related impacts at regional scale: the case of Mediterranean region. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narra, P.; Coelho, C.; Sancho, F.; Palalane, J. CERA: an open-source tool for coastal erosion risk assessment. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Martino, G. Assessment of maritime erosion index for Ionian-Lucanian coast. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, G. Master Plan of solutions to mitigate the risk of coastal erosion in Calabria (Italy), a case study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 132, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benassai, G.; Di Paola, G.; Aucelli, P.P.C. Coastal risk assessment of a micro-tidal littoral plain in response to sea level rise. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 104, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucelli, P.P.C.; Di Paola, G.; Rizzo, A.; Rosskopf, C.M. Rischio all’erosione costiera del settore meridionale della costa molisana. Studi Costieri 2017, 26, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Armaroli, C.; Duo, E. Validation of the coastal storm risk assessment framework along the Emilia-Romagna coast. Coast. Eng. 2018, 134, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantusa, D.; D’Alessandro, F.; Riefolo, L.; Principato, F.; Tomasicchio, G. Application of a coastal vulnerability index. A case study along the Apulian Coastline, Italy. Water 2018, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, D.; Pinna, M. S.; Alquini, F.; Cogoni, D.; Ruocco, M.; Bacchetta, G.; Sarti, G.; Fenu, G. Development of a coastal dune vulnerability index for Mediterranean ecosystems: A useful tool for coastal managers? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 187, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, S.; Critto, A.; Rizzi, J.; Marcomini, A. Assessment of coastal vulnerability to climate change hazards at the regional scale: the case study of the North Adriatic Sea. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 2347–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. F.; Martinho, M.; Capitão, R.; Reis, T.; Fortes, C. J.; Ferreira, J. C. An index-based method for coastal-flood risk assessment in low-lying areas (Costa de Caparica, Portugal). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 144, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatidi, A.; Briche, E.; Claeys, C. Mapping and analyzing socio-environmental vulnerability to coastal hazards induced by climate change: an application to coastal Mediterranean cities in France. Cities 2018, 72, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, J.M.; Hansom, J.D.; Rennie, A.F. A national coastal erosion susceptibility model for Scotland. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 132, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantamaneni, K.; Phillips, M.; Thomas, T.; Jenkins, R. Assessing coastal vulnerability: Development of a combined physical and economic index. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 158, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S. A. Coastal vulnerability assessment using GIS-Based multicriteria analysis of Alexandria-northwestern Nile Delta, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2020, 163, 103751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Jahangir, S.; Azhoni, A. GIS based coastal vulnerability assessment and adaptation barriers to coastal regulations in Dakshina Kannada district, India. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 55, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pandit, S.; Papia, M.; Rahman, M. M.; Ocampo, J. C. O. R.; Razi, M. A. . Hossain, M. S. Coastal erosion risk assessment in the dynamic estuary: The Meghna estuary case of Bangladesh coast. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumurthy, S.; Jayanthi, M.; Samynathan, M.; Duraisamy, M.; Kabiraj, S.; Anbazhahan, N. Multi-criteria coastal environmental vulnerability assessment using analytic hierarchy process based uncertainty analysis integrated into GIS. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 313, 114941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, E. H.; Mathew, M. J.; Roslee, A.; Ismailluddin, A.; Yun, L. S.; Putra, A. B. . Lee, L. H. A multi-hazards coastal vulnerability index of the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 84, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzehkar, M.; Parnell, K.; Soomere, T. Extending multi-criteria coastal vulnerability assessment to low-lying inland areas: examples from Estonia, eastern Baltic Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 311, 109014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Sridharan, B.; Saha, N.; Sannasiraj, S. A.; Kuiry, S. N. Assessment of coastal vulnerability for extreme events. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 82, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.A.; Mondal, I.; Thakur, S.; Al-Quraishi, A. M. F. Coastal vulnerability assessment of India's Purba Medinipur-Balasore coastal stretch: A comparative study using empirical models. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, O.; Sergeev, A.; Ryabchuk, D. Coastal vulnerability index as a tool for current state assessment and anthropogenic activity planning for the Eastern Gulf of Finland coastal zone (the Baltic Sea). Appl. Geogr. 2022, 143, 102710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzirafuti, A.; Theocharidis, C. Coastal Vulnerability Index Assessment Along the Coastline of Casablanca Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativí-Merchán, S.; Caiza-Quinga, R.; Saltos-Andrade, I.; Martillo-Bustamante, C.; Andrade-García, G.; Quiñonez, M. . Cedeño, J. Coastal erosion assessment using remote sensing and computational numerical model. Case of study: Libertador Bolivar, Ecuador. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 214, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.; Antunes, C.; Catita, C. Coastal indices to assess sea-level rise impacts-A brief review of the last decade. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 237, 106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, F.; García-Ayllón, S. Coastal resilience potential as an indicator of social and morphological vulnerability to beach management. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 253, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwyn-Paulson, P.; Jonathan, M. P.; Rodríguez-Espinosa, P. F.; Rahaman, S. A.; Roy, P. D.; Muthusankar, G.; Lakshumanan, C. Multi-hazard risk assessment of coastal municipalities of Oaxaca, Southwestern Mexico: An index based remote sensing and geospatial technique. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laino, E.; Iglesias, G. Beyond coastal hazards: A comprehensive methodology for the assessment of climate-related hazards in European coastal cities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 257, 107343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.F.; Motta Zanin, G.; Barbanente, A.; Damiani, L. Understanding the cognitive components of coastal risk assessment. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, G.; Re, C.L.; Basile, M.; Ciraolo, G. A new shoreline change assessment approach for erosion management strategies. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 225, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo Queiroz, H. A.; Gonçalves, R. M.; Mishra, M. Characterizing global satellite-based indicators for coastal vulnerability to erosion management as exemplified by a regional level analysis from Northeast Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennouali, Z.; Fannassi, Y.; Lahssini, G.; Benmohammadi, A.; Masria, A. Mapping coastal vulnerability using machine learning algorithms: A case study at North coastline of Sebou estuary, Morocco. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 60, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townend, I. H.; French, J. R.; Nicholls, R. J.; Brown, S.; Carpenter, S.; Haigh, I. D.; … Tompkins, E. L. Operationalising coastal resilience to flood and erosion hazard: A demonstration for England. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unguendoli, S.; Biolchi, L. G.; Aguzzi, M.; Pillai, U. P. A.; Alessandri, J.; Valentini, A. A modeling application of integrated nature based solutions (NBS) for coastal erosion and flooding mitigation in the Emilia-Romagna coastline (Northeast Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, A. B.; Riley, T. N.; Steenrod, C. L.; Puckett, B. J.; Alemu I, J. B.; Paliotti, S. T. . Silliman, B. R. Evidence on the performance of nature-based solutions interventions for coastal protection in biogenic, shallow ecosystems: a systematic map. Environ. Evid. 2024, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berre, I.L.; Meur-Ferec, C. Systemic vulnerability of coastal territories to erosion and marine flooding: A conceptual and methodological approach applied to Brittany (France). Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 78, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, K.; Dey, P. Coastal vulnerability analysis and RIDIT scoring of socio-economic vulnerability indicators–A case of Jagatsinghpur, Odisha. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 79, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucerino, L.; Albarella, M.; Carpi, L.; Besio, G.; Benedetti, A.; Corradi, N. . & Ferrari, M. Coastal exposure assessment on Bonassola bay. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 167, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, E.A.; Thieler, R.S.; Williams, J. Coastal vulnerability assessment of Fire Island National seashore (FIIS) to Sea level Rise. USGS Open File Rep. 2004, 03, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M. O. Barrier island morphology as a function of tidal and wave regime. In Barrier Islands; Leatherman, S.P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 1, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnold, R.A. The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes; William Morrow &, Co. : New York, NY, USA, 1941.

- Hsu, S. Computing eolian sand transport from routine weather data. Coast. Eng. Proc. 1974, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdon, H. F.; Holman, R. A.; Howd, P. A.; Sallenger Jr, A. H. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 2006, 53, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Costas, S. Process-based indicators to assess storm induced coastal hazard. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 173, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Barillà, G.C.; Mancuso, P.; Puntorieri, P. Shoreline evolutionary trends along calabrian coasts: Causes and classification. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 846914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.; Odériz, I.; Martínez, M.L.; Silva, R. Measurements and modelling of small scale processes of vegetation preventing dune erosion. J. Coast. Res. 2017, 77, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedan, K.B.; Kirwan, M.L.; Wolanski, E.; Barbier, E. B.; Silliman, B. R. The present and future role of coastal wetland vegetation in protecting shorelines: answering recent challenges to the paradigm. Clim. Change 2011, 106, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagin, R.A.; Furman, M.; Salgado, K.; Martinez, M. L.; Innocenti, R. A.; Eubanks, K. . Silva, R. The role of beach and sand dune vegetation in mediating wave run up erosion. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 219, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresque, C.F.; Bernard, G.; Bonhomme, P.; Charbonnel, E.; Diviacco, G.; Meinesz, A.; Pergent, G.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Ruitton, S.; Tunesi, L. Protection and Conservation of Posidonia Oceanica Meadows; RAC/SPA: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Trogu, D.; Simeone, S.; Ruju, A.; Porta, M.; Ibba, A.; DeMuro, S. A Four-Year Video Monitoring Analysis of the Posidonia oceanica Banquette Dynamic: A Case Study from an Urban Microtidal Mediterranean Beach (Poetto Beach, Southern Sardinia, Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo-Gutierrez, C.; Rabionet, I.C.; Garcia, V.G.; Pedrico, J. P. S.; Conejo, A. S. A. Study of velocity changes induced by Posidonia oceanica surrogate and sediment transport implications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekovski, I.; Del Río, L.; Armaroli, C. Development of a coastal vulnerability index using analytical hierarchy process and application to Ravenna province (Italy). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 183, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, F.; Anthony, E.J.; Héquette, A.; Suanez, S.; Musereau, J.; Ruz, M.H.; Regnauld, H. Morphodynamics of beach/dune systems: Examples from the coast of France. Géomorphologie: Relief, Processus, Environnement 2009, 15, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, F.; Abreu, T.; D’Alessandro, F.; Tomasicchio, G. R.; Silva, P. A. Surf hydrodynamics in front of collapsing coastal dunes. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, D.; Greggio, N.; Antonellini, M.; Giambastiani, B. M. S. Natural and anthropogenic factors affecting freshwater lenses in coastal dunes of the Adriatic coast. J. Hydrol. 2017, 551, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, J. W. Static and dynamic stability of loose material. In Coastal Protection; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 157–195. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, A.; Lombardo, S.; Doody, P. Living with Coastal Erosion in Europe: Sediment and Space for Sustainability; EUROSION Project Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Censimento permanente. Available online: http://dati-censimentipermanenti.istat.it/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Corine Land Cover. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/attivita/suolo-e-territorio/suolo/copertura-del-suolo/corine-land-cover (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Calabrian Geoportal. Available online: https://geoportale.regione.calabria.it/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- ISPRA. Direttiva Alluvioni—Documenti. Available online: https://gn.mase.gov.it/portale/documents/d/geoportale-mase/documento_definitivo_indirizzi_operativi_direttiva_alluvioni_gen_13 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- ISPRA. Mappatura del rischio costiero; ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlington, B. D.; Bellas-Manley, A.; Willis, J. K.; Fournier, S.; Vinogradova, N.; Nerem, R. S. . Kopp, R. The rate of global sea level rise doubled during the past three decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MeteOcean Group – DICCA, University of Genoa. Available online: https://forecast.meteocean.science/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- National tidal network – RMN (ISPRA). Available online: https://www.mareografico.it/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Sannino, G.; Carillo, A.; Pisacane, G.; Naranjo, C. On the relevance of tidal forcing in modeling the Mediterranean thermohailine circulation. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015, 134, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosetti, F. Some News on the Currents in the Straits of Messina. Boll. Oceanol. Teor. Appl. 1988, 6, 119–201. [Google Scholar]

- Coiro, D.P.; Lioniello, F.; Troise, G. Misura del profilo di corrente marina nello stretto di Messina ai fini della stima della produzione di energia. ENEA Report RdS/2013/087, 2013.

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Besio, G.; Barillà, G. C.; Mancuso, P.; Puntorieri, P. Wave climate along Calabrian coasts. Climate 2022, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Calabria. Indagine conoscitiva dello stato delle coste calabresi, predisposizione di una banca dati dell’evoluzione del litorale e individuazione delle aree a rischio e delle tipologie di intervento studi su aree campione e previsione delle relative opere di difesa. 2003.

- EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM 2020). EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium. (accessed on 21 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Italian Geoportal. Available online: https://gn.mase.gov.it/portale/home (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- MEDISEH Project. Available online: https://imbriw.hcmr.gr/mediseh/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Barillà, G.C.; Frega, F. Effects of anthropogenic pressures on dune systems. Case study: Calabria (Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisotti, G. A Case of Induced Subsidence for Extraction of Salt by Hydrosolution. In Proc. 4th Int. Symp. Land Subsidence, Houston, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 12–17.

- Cherubini, C.; Cotecchia, V.; Pagliarulo, R. Subsidence in the Sybaris Plain (Italy). In Land Subsidence. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Land Subsidence, Volume 1, 2000.

- Raspini, F.; Cigna, F.; Moretti, S. Multi-temporal mapping of land subsidence at basin scale exploiting Persistent Scatterer Interferometry: Case study of Gioia Tauro plain (Italy). J. Maps 2012, 8, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, F.; Cotecchia, F.; Lenti, V. Interpretation and modelling of the subsidence at the archeaelogical site odf Sybaris (Southern Italy). In Geotechnical Engineering for the Preservation of Monuments; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2013; pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe, F.; Bertotti, G.; Ferranti, L.; Sacchi, M.; Collura, A. M.; Passaro, S.; Sulli, A. Pattern and rate of post-20 ka vertical tectonic motion around the Capo Vaticano Promontory (W Calabria, Italy) based on offshore geomorphological indicators. Quat. Int. 2014, 332, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianflone, G.; Tolomei, C.; Brunori, C.A.; Dominici, R. InSAR time series analysis of natural and anthropogenic coastal plain subsidence: The case of Sibari (Southern Italy). Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 16004–16023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianflone, G.; Tolomei, C.; Brunori, C.A.; Dominici, R. Preliminary study of the surface ground displacements in the Crati Valley (Calabria) by means of InSAR data. Rend. Online Soc. Geol. Ital. 2015, 33, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, F.; Confuorto, P.; Novellino, A.; Tapete, D.; Di Martire, D.; Ramondini, M.; Sowter, A. 25 Years of Satellite InSAR Monitoring of Ground Instability and Coastal Geohazards in the Archaeological Site of Capo Colonna, Italy. In Proceedings of the SAR Image Analysis, Modeling, and Techniques XVI, Edinburgh, UK, 26–29 September 2016; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume 10003, pp. 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confuorto, P.; Plank, S.; Novellino, A.; Tessitore, S.; Ramondini, M. Implementation of DInSAR Methods for the Monitoring of the Archaeological Site of Hera Lacinia in Crotone (Southern Italy). Rend. Online Soc. Geol. Ital. 2016, 41, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, F.; Tapete, D. Sentinel-1 big data processing with P-SBAS InSAR in the geohazards exploitation platform: An experiment on coastal land subsidence and landslides in Italy. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Bombino, G.; Barillà, G. C.; Mancuso, P.; Puntorieri, P. River transport in Calabrian rivers. In New Metropolitan Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilovic, S. Méthode de la classification des bassins torrentiels et équations nouvelles pour le calcul des hautes eaux et du débit solide. Vadopriveda 1959, Belgrade, Serbia. [Google Scholar]

- Calabria Multi-Risk Functional Center. Available online: http://www.cfd.calabria.it/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Tomasicchio, G.R.; D’Alessandro, F.; Barbaro, G.; Malara, G. General longshore transport model. Coast. Eng. 2013, 71, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Barillà, G.C.; Mancuso, P. Shoreline changes due to the construction of ports: case study—Calabria (Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sea Level Projection Tool – NASA. Available online: https://sealevel.nasa.gov/ipcc-ar6-sea-level-projection-tool (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Barillà, G.C.; Mancuso, P; Puntorieri P. Shoreline erosion due to anthropogenic pressure in Calabria (Italy). Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 56, 2140076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, P.; Caputo, C.; Davoli, L.; Evangelista, S.; Pugliese, F. Coastal protections in Tyrrhenian Calabria (Italy): Morphological and sedimentological feedback on the vulnerable area of Belvedere Marittimo. Geogr. Fis. Din. Quat. 2009, 32, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, F.; Tomasicchio, G.R.; Frega, F.; Carbone, M. Design and management aspects of a coastal protection system. A case history in the South of Italy. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 64, 492–495. [Google Scholar]

- Ietto, F.; Cantasano, N.; Pellicone, G. A new coastal erosion risk assessment indicator: Application to the Calabria Tyrrhenian Littoral (southern Italy). Environ. Process. 2018, 5, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantasano, N.; Pellicone, G.; Ietto, F. The coastal sustainability standard method: A case study in Calabria (southern Italy). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 183, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication | Application scale | Application area |

SLR* | T* | WC* | R* | LST* | RST* | CG* | SET* | ECM* | SCM* | DS* | V* | CDS* | PS* | CSI* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greco & Martino, 2014 [15] |

Regional | Basilicata (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Barbaro, 2016 [16] | Regional | Calabria (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Benassai et al., 2015 [17] | Sub-regional | Campania (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Aucelli P. et al., 2017 [18] | Regional | Molise (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Armaroli & Duo, 2018 (CRAF) [19] | Regional | Emilia-Romagna (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Pantusa et al., 2018 [20] | Local | Apulia (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ciccarelli et al., 2017 [21] | Regional | Tuscany & Sardinia (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Torresan et al., 2012 [22] | Regional | Friuli-Venezia Giulia (Italy) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ferreira Silva et al., 2017 [23] | Local | Portugal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mavromatidi et al., 2018 [24] | Regional | France | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Fitton et al., 2016 [25] | Local | Scotland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Kantamaneni et al., 2018 [26] | Local | United Kingdom | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Satta et al., 2016 (MS-CRI) [12] |

Local | Morocco | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Satta et al., 2017 (CRI-MED) [13] | International | Mediterranean countries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Narra et al., 2017 (CERA) [14] |

Local | Portugal & Mozambique | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Mohamed, 2020 [27] | Sub-regional | Egypt | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Rehman et al., 2022 [28] | Local | India | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Roy et al., 2021 [29] | Regional | Bangladesh | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Thirumurthy et al., 2022 [30] | Local | India | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ariffin et al., 2023 [31] | Sub-national | Malaysia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Barzehkar et al., 2024 [32] | National | Estonia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ahmed et al., 2022 [33] | Local | India | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Hossain et al., 2022 [34] | Sub-regional | India | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kovaleva et al., 2022 [35] | Regional | Russia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Muzirafuti & Theocharidis, 2025 [36] | Local | Morocco | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Nativí-Merchán et al., 2021 [37] | Local | Ecuador | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Godwyn-Paulson et al., 2022 [40] | Sub-national | Mexico | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Laino & Iglesias, 2024 [41] | Local | European coastal cities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ennouali et al., 2023 [45] | Local | Morocco | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mandal & Dey, 2022 [50] | Sub-national | India | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| N. | Sample area | N. | Sample area | N. | Sample area | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Montegiordano | 19 | San Sostene | 37 | Palmi | ||||||||

| 2 | Roseto Capo Spulico | 20 | Badolato | 38 | San Ferdinando | ||||||||

| 3 | Trebisacce | 21 | Monasterace | 39 | Ricadi (Santa Maria) | ||||||||

| 4 | Villapiana | 22 | Riace | 40 | Capo Vaticano | ||||||||

| 5 | Rossano | 23 | Caulonia | 41 | Tropea | ||||||||

| 6 | Calopezzati | 24 | Roccella Ionica | 42 | Vibo Marina | ||||||||

| 7 | Cariati | 25 | Locri | 43 | Gizzeria | ||||||||

| 8 | Crucoli (Torretta) | 26 | Bovalino | 44 | Falerna | ||||||||

| 9 | Cirò Marina | 27 | Ferruzzano | 45 | Amantea | ||||||||

| 10 | Torre Melissa | 28 | Brancaleone | 46 | Belmonte | ||||||||

| 11 | Crotone (Zigari) | 29 | Palizzi | 47 | San Lucido | ||||||||

| 12 | Crotone | 30 | Bova Marina | 48 | Fuscaldo | ||||||||

| 13 | Isola Capo Rizzuto (Marinella) | 31 | Melito Porto Salvo | 49 | Cetraro | ||||||||

| 14 | Isola Capo Rizzuto | 32 | Lazzaro | 50 | Sangineto | ||||||||

| 15 | Isola Capo Rizzuto (Le Castella) | 33 | Reggio Calabria (Pellaro) | 51 | Belvedere | ||||||||

| 16 | Cropani | 34 | Reggio Calabria (Gallico) | 52 | Santa Maria del Cedro | ||||||||

| 17 | Catanzaro Lido | 35 | Villa San Giovanni (Porticello) | 53 | Scalea | ||||||||

| 18 | Soverato | 36 | Scilla (Favazzina) | 54 | Tortora | ||||||||

| Hazard/ Vulnerability/ Exposure Level | // | |||||

| Low | < 20 % | |||||

| Medium – low | 20 ÷ 40 % | |||||

| Medium | 40 ÷ 60 % | |||||

| Medium – high | 60 ÷ 80 % | |||||

| High | ≥ 80 % |

| Hazard Classes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDEX | Very low 1 |

Low 2 |

Moderate 3 |

High 4 |

Very high 5 |

|||||

| SLR [mm/year] | 0.2 | < 1.8 | 1.8 ÷ 2.5 | 2.5 ÷ 3.0 | 3.0 ÷ 3.4 | ≥ 3.4 | ||||

| Tidal range [m] | 0.1 | < 1 | 1÷ 2 | 2 ÷ 3.5 | 3.5 ÷ 5 | ≥ 5 | ||||

| Marine Currents [knots] | 0.1 | < 0.5 | 0.5 ÷ 1.5 | 1.5 ÷ 3 | 3 ÷ 5 | ≥ 5 | ||||

| Wind (Aeolian Deflation) [%] | 0.1 | < 5 | 5 ÷ 15 | 15 ÷ 25 | 25 ÷ 35 | ≥ 35 | ||||

| Wave Climate | 0.5 | < 0.2 | 0.2 ÷ 0.4 | 0.4 ÷ 0.6 | 0.6 ÷ 0.8 | ≥ 0.8 | ||||

| Vulnerability Classes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDEX | Very low 1 |

Low 2 |

Moderate 3 |

High 4 |

Very high 5 |

|||||||

| Coastal type | 1/11 | High rocky coasts |

Medium cliffs, irregular coasts |

Low cliffs, alluvial plains | Sandy beaches, estuaries, lagoons | Sandy beaches, dune systems | ||||||

| Emerged Coastal Morphology (ECM) |

Beach slope [%] (w = 0.5) | 1/11 | ≥ 12 | 12 ÷ 9 | 9 ÷ 6 | 6 ÷ 3 | < 3 | |||||

| Mean beach width [m] (w = 0.5) | ≥ 80 | 80 ÷ 60 | 60 ÷ 40 | 40 ÷ 20 | < 20 | |||||||

| Submerged Coastal Morphology – Seafloor slope [%] |

1/11 | < 2 | 2 ÷ 6 | 6 ÷ 10 | 10 ÷ 20 | ≥ 20 | ||||||

| Sediment Transport (ST) | 1/11 | ≥ 1 | 1 ÷ 0.75 | 0.75 ÷ 0.5 | 0.5 ÷ 0.25 | < 0.25 | ||||||

| Shoreline Evolutionary Trend (SET) [m/year] | 1/11 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 ÷ -0.5 | -0.5 ÷ -1.0 | -1.0 ÷ -2.0 | < -2.0 | ||||||

| Subsidence (S) [mm/year] | 1/11 | ≥ - 1 | - 1 ÷ - 4 | - 4 ÷ - 7 | - 7 ÷ - 10 | < - 10 | ||||||

| Vegetation (V) | Average vegetation width [m] (w = 0.4) | 1/11 | ≥ 100 | 75 ÷ 100 | 50 ÷ 75 | 25 ÷ 50 | < 25 | |||||

| Percentage of vegetative coverage [%] (w = 0.4) | ≥ 80 | 80 ÷ 60 | 60 ÷ 40 | 40 ÷ 20 | < 20 | |||||||

| Posidonia Oceanica (w = 0.2) | Presence (0) / Absence (5) | |||||||||||

| Dune Systems (DS) | Average dune elevation [m] (w = 0.3) | 1/11 | ≥ 6 | 4 ÷ 6 | 2 ÷ 4 | 1 ÷ 2 | < 1 | |||||

| Average dune width [m] (w = 0.3) | ≥ 100 | 75 ÷ 100 | 50 ÷ 75 | 25 ÷ 50 | < 25 | |||||||

| Percentage of coastline protected by dunes [%] (w = 0.4) | ≥ 80 | 80 ÷ 60 | 60 ÷ 40 | 40 ÷ 20 | < 20 | |||||||

| Coastal Defense Structures (CDS) [%] | 1/11 | ≥ 80 | 80 ÷ 60 | 60 ÷ 40 | 40 ÷ 20 | < 20 | ||||||

| Port Structures (PS) | 1/11 | < 0.2 | 0.2 ÷ 0.4 | 0.4 ÷ 0.6 | 0.6 ÷ 0.8 | ≥ 0.8 | ||||||

| Coastal Anthropization (CA) [%] | 1/11 | ≥ 80 | 80 ÷ 60 | 60 ÷ 40 | 40 ÷ 20 | < 20 | ||||||

| Exposure Classes | ||||||||||

| INDEX |

Very low 1 |

Low 2 |

Moderate 3 |

High 4 |

Very high 5 |

|||||

| Resident population in the hazard area [inhabitants] |

0.2 | < 1000 | 1000 ÷ 5000 | 5000 ÷ 10000 | 10000 ÷ 20000 | ≥ 20000 | ||||

| Land-Use Classes | 0.8 | Inland and coastal wetlands, Continental and marine waters, Bare rocks, cliffs, and rocky outcrops | Wooded areas, Natural grasslands and pastures, Sparsely vegetated areas, Transitional woodland-shrub vegetation areas, Sclerophyllous vegetation areas, Beaches, dunes, and sands | Arable land, Permanent crops (vineyards, olive groves, orchards, etc.), Heterogeneous agricultural areas | Extractive areas, Landfills, Cemeteries, Geosites | Residential urban areas, Industrial, commercial, and infrastructural areas, Construction sites, Urban green areas, Recreational and sports areas, Historical monuments and/or archaeological sites, Oases and nature reserves, National and Regional Parks, SACs, SINs, SIRs | ||||

| Risk Level | |

| Low | < 5% |

| Medium - low | 5 ÷ 15 % |

| Medium | 15 ÷ 30 % |

| Medium – high | 30 ÷ 50 % |

| High | ≥ 50 % |

| Data | Data source | Period | |

| SLR (mm/year) | Literature studies [76] | 1993-2023 | |

| SLR projections (mm/year) | Sea Level Projection Tool [103] | - | |

| Hydrometric level data (m) | Tide gauge records – RMN (ISPRA) [78] | 2010-2021 | |

| Current velocity (knots) | Literature studies [80,81] | - | |

| Wind data (wind speed and direction) | MeteOcean Group – DICCA, University of Genoa [77] | 1979-2018 | |

| Wave data (Hs, Tp, Tm, Dir) | MeteOcean Group – DICCA, University of Genoa [77] | 1979-2018 | |

| Temperature data | Calabria Multi-Risk Functional Center [100] | 1916–present | |

| Rainfall data | Calabria Multi-Risk Functional Center [100] | 1916–present | |

| Coastline orientation | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Subsidence (mm/year) | Literature studies [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97] | - | |

| Beach slope (%) | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Beach width (m) | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Dn50 (mm) | OKEANOS (2003) [83] | 2003 | |

| Foreshore beach slope (m) |

EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM 2020) [84] |

2020 |

|

| Shoreline change rate (m/year) | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2015-2021 | |

| Historical shorelines – Calabrian Geoportal [73] | 1954; 1998; 2000; 2008 | ||

| Orthophotos – Italian Geoportal [85] |

1989; 1996; 2006; 2012 |

||

| Elevation | DTM 5x5 m – Calabrian Geoportal [73] | 2008 | |

| Land use and land cover data (LULC data) | Level IV Corine Land Cover (2018) dataset [72] | 2018 | |

| Posidonia Oceanica | MEDISEH Project [86] | 2013 | |

| Coastal vegetation characteristics | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Dunal system characteristics | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Coastal Defense Structures and Ports | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Coastal Anthropization | Satellite Imagery (Google Earth) | 2021 | |

| Population | ISTAT Dataset [71] | 2020 |

| N. | Hazard level | N. | Hazard level | N. | Hazard level | |||||

| 1 | 0.45 | Medium | 19 | 0.48 | Medium | 37 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 2 | 0.45 | Medium | 20 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 38 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 3 | 0.45 | Medium | 21 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 39 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 4 | 0.45 | Medium | 22 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 40 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 5 | 0.45 | Medium | 23 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 41 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 6 | 0.45 | Medium | 24 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 42 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 7 | 0.45 | Medium | 25 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 43 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 8 | 0.45 | Medium | 26 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 44 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 9 | 0.58 | Medium | 27 | 0.63 | Medium – high | 45 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 10 | 0.58 | Medium | 28 | 0.63 | Medium – high | 46 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 11 | 0.58 | Medium | 29 | 0.48 | Medium | 47 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 12 | 0.45 | Medium | 30 | 0.48 | Medium | 48 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 13 | 0.58 | Medium | 31 | 0.48 | Medium | 49 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 14 | 0.58 | Medium | 32 | 0.48 | Medium | 50 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 15 | 0.48 | Medium | 33 | 0.48 | Medium | 51 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 16 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 34 | 0.50 | Medium | 52 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 17 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 35 | 0.78 | Medium – high | 53 | 0.73 | Medium – high | ||

| 18 | 0.48 | Medium | 36 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 54 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| N. | Vulnerability level | N. | Vulnerability level | N. | Vulnerability level | |||||

| 1 | 0.56 | Medium | 19 | 0.41 | Medium | 37 | 0.49 | Medium | ||

| 2 | 0.52 | Medium | 20 | 0.35 | Medium - low | 38 | 0.49 | Medium | ||

| 3 | 0.44 | Medium | 21 | 0.42 | Medium | 39 | 0.55 | Medium | ||

| 4 | 0.35 | Medium - low | 22 | 0.34 | Medium - low | 40 | 0.57 | Medium | ||

| 5 | 0.42 | Medium | 23 | 0.42 | Medium | 41 | 0.59 | Medium | ||

| 6 | 0.54 | Medium | 24 | 0.57 | Medium | 42 | 0.51 | Medium | ||

| 7 | 0.66 | Medium – high | 25 | 0.46 | Medium | 43 | 0.45 | Medium | ||

| 8 | 0.51 | Medium | 26 | 0.41 | Medium | 44 | 0.53 | Medium | ||

| 9 | 0.66 | Medium – high | 27 | 0.46 | Medium | 45 | 0.64 | Medium – high | ||

| 10 | 0.56 | Medium | 28 | 0.48 | Medium | 46 | 0.64 | Medium – high | ||

| 11 | 0.53 | Medium | 29 | 0.52 | Medium | 47 | 0.56 | Medium | ||

| 12 | 0.62 | Medium – high | 30 | 0.62 | Medium – high | 48 | 0.59 | Medium | ||

| 13 | 0.56 | Medium | 31 | 0.50 | Medium | 49 | 0.63 | Medium – high | ||

| 14 | 0.44 | Medium | 32 | 0.69 | Medium – high | 50 | 0.59 | Medium | ||

| 15 | 0.44 | Medium | 33 | 0.65 | Medium – high | 51 | 0.51 | Medium | ||

| 16 | 0.35 | Medium - low | 34 | 0.56 | Medium | 52 | 0.35 | Medium - low | ||

| 17 | 0.47 | Medium | 35 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 53 | 0.39 | Medium - low | ||

| 18 | 0.41 | Medium | 36 | 0.58 | Medium | 54 | 0.44 | Medium | ||

| N. | Exposure level | N. | Exposure level | N. | Exposure level | |||||

| 1 | 0.40 | Medium | 19 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 37 | 0.40 | Medium | ||

| 2 | 0.40 | Medium | 20 | 0.40 | Medium | 38 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 3 | 0.40 | Medium | 21 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 39 | 0.40 | Medium | ||

| 4 | 0.40 | Medium | 22 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 40 | 0.40 | Medium | ||

| 5 | 0.65 | Medium – high | 23 | 0.80 | High | 41 | 0.20 | Medium - low | ||

| 6 | 0.40 | Medium | 24 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 42 | 0.45 | Medium | ||

| 7 | 0.40 | Medium | 25 | 0.00 | Low | 43 | 0.80 | High | ||

| 8 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 26 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 44 | 0.80 | High | ||

| 9 | 0.40 | Medium | 27 | 0.40 | Medium | 45 | 0.20 | Medium - low | ||

| 10 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 28 | 0.40 | Medium | 46 | 0.20 | Medium - low | ||

| 11 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 29 | 0.40 | Medium | 47 | 0.20 | Medium - low | ||

| 12 | 0.60 | Medium – high | 30 | 0.40 | Medium | 48 | 0.20 | Medium - low | ||

| 13 | 0.00 | Low | 31 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 49 | 0.80 | High | ||

| 14 | 0.00 | Low | 32 | 0.80 | High | 50 | 0.40 | Medium | ||

| 15 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 33 | 0.80 | High | 51 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 16 | 0.40 | Medium | 34 | 0.85 | High | 52 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 17 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 35 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 53 | 0.60 | Medium – high | ||

| 18 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 36 | 0.20 | Medium - low | 54 | 0.20 | Medium - low | ||

| N. | Risk level | N. | Risk level | N. | Risk level | |||||

| 1 | 0.10 | Medium - low | 19 | 0.12 | Medium - low | 37 | 0.14 | Medium - low | ||

| 2 | 0.09 | Medium - low | 20 | 0.08 | Medium - low | 38 | 0.18 | Medium | ||

| 3 | 0.08 | Medium - low | 21 | 0.05 | Low | 39 | 0.13 | Medium - low | ||

| 4 | 0.06 | Medium - low | 22 | 0.04 | Low | 40 | 0.16 | Medium | ||

| 5 | 0.12 | Medium - low | 23 | 0.20 | Medium | 41 | 0.09 | Medium - low | ||

| 6 | 0.10 | Medium - low | 24 | 0.07 | Medium - low | 42 | 0.14 | Medium - low | ||

| 7 | 0.12 | Medium - low | 25 | 0.00 | Low | 43 | 0.21 | Medium | ||

| 8 | 0.14 | Medium - low | 26 | 0.05 | Low | 44 | 0.30 | Medium – high | ||

| 9 | 0.15 | Medium | 27 | 0.12 | Medium - low | 45 | 0.09 | Medium - low | ||

| 10 | 0.06 | Medium - low | 28 | 0.12 | Medium - low | 46 | 0.09 | Medium - low | ||

| 11 | 0.18 | Medium | 29 | 0.10 | Medium - low | 47 | 0.08 | Medium - low | ||

| 12 | 0.17 | Medium | 30 | 0.12 | Medium - low | 48 | 0.09 | Medium - low | ||

| 13 | 0.00 | Low | 31 | 0.05 | Low | 49 | 0.36 | Medium – high | ||

| 14 | 0.00 | Low | 32 | 0.26 | Medium | 50 | 0.17 | Medium | ||

| 15 | 0.04 | Low | 33 | 0.25 | Medium | 51 | 0.22 | Medium | ||

| 16 | 0.08 | Medium - low | 34 | 0.24 | Medium | 52 | 0.15 | Medium | ||

| 17 | 0.06 | Medium - low | 35 | 0.09 | Medium - low | 53 | 0.17 | Medium | ||

| 18 | 0.04 | Low | 36 | 0.07 | Medium - low | 54 | 0.05 | Medium - low | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).