1. Introduction

A clean-burning fuel composed of biomass called bioethanol is garnering a lot of prominence as a possible substitute for fossil fuels. Global bioethanol production reached a record high of 107 billion litres in 2023, highlighting its growing importance [

1]. However, optimizing production efficiency remains crucial for broader adoption. This study delves into optimizing bioethanol production from three promising feedstocks with the potential to address current limitations: vegetable waste, lignocellulosic biomass like switchgrass, and marine algae. Each feedstock presents unique advantages and challenges. Vegetable waste, with an estimated global generation exceeding 3.3 billion tonnes annually, offers readily available resources but requires efficient collection and handling to minimize contamination and ensure sustainability [

2]. Lignocellulosic biomass provides a dedicated energy crop option but necessitates pre-treatment to break down its complex structures for efficient conversion. Marine algae boast rapid growth rates, exceeding 30% per day for some species, and minimal competition for land resources, but require further development of large-scale cultivation and harvesting technologies. Generally, feedstock sources including wheat, sugarcane, corn, straw, and wood are used to make bioethanol from plant waste as well as agricultural waste like wildlife waste, woodland debris, harvest leftovers, and herbaceous plants. The primary issue with bioethanol production is that, despite the variety of feedstocks available, the supply of raw materials varies greatly from season to season due to the need for a systematic framework.

2. Vegetable Profiles for Bioethanol Production

Vegetables including root vegetables, some starchy vegetables, and even processing wastes, which have a high starch content, good water content, and easily accessible cellulose, are ideal for producing bioethanol. Their water concentration increases processing efficiency while their starch breaks down into fermentable sugars. Despite not being directly fermentable, cellulose can be pre-treated to turn it into sugars. Vegetables have benefits too, such as year-round availability and decreased waste. Vegetables that are extra, imperfect, or unsuitable can be used to produce bioethanol, which encourages the use of a more sustainable source of biofuel. This strategy makes efficient use of the resources already available, avoiding conflict with food security.

2.1. Potato Peels (Solanum tuberosum)

The residue left after industrial potato processing, or potato peel waste (PPW), can make up 15–40% of the original potato mass, depending on how the potato is peeled [

3]. Due to its high starch content, PPW is an excellent feedstock for the synthesis of bioethanol. S. cerevisiae is used to ferment potato peel waste and for examining the effects of yeast extract concentration on ethanol generation. To do this, hydrochloric acid (HCl) was used in an acid hydrolysis procedure on potato peels to convert complex polysaccharides into simpler, fermentable sugars. Two strains of S. cerevisiae were used, one that was genetically engineered and the other that was commercially available [

4]. The effects of yeast extract concentration and the length of the fermentation process were checked often. Following the study, a three to four-day fermentation period was perfect, and a yeast extract concentration of two grams per litre was ideal for providing nitrogen. To ensure healthy and active yeast for fermentation, separate procedures were followed for culturing and maintaining the strains. A specific growth medium provided optimal conditions for both the commercially available and genetically modified S. cerevisiae strains. The commercial strain underwent an additional purification step to eliminate bacterial contamination. To maintain viability, stock cultures were stored at 4°C and refreshed by transferring them to new media every 3 weeks. Finally, a distinct inoculum medium was used to cultivate actively growing yeast cells specifically for the fermentation process. Production began slowly in the absence of yeast extract, producing nothing on the first day and just an increase in a small amount by the second. On day four, it peaked at 1.2%, and on day five, it declined somewhat. The highest ethanol production was observed between 72 and 96 hours (3rd and 4th day) in all cases except the zero-yeast extract example. The first day's production was very low without any yeast extract, but it increased significantly by the second day, peaked on the fourth, and then slightly decreased on the fifth. Ethanol yield generally rose as yeast extract concentrations increased (2 g/L to 8 g/L). It's interesting to note that, with a potential sweet spot, higher ethanol generation was often associated with rising yeast extract concentrations. By day four, both yeast species had reached their maximum output (about 2.17%) at 2 g/L. However, because there could be a mistake, this value at 96 hours (day 4) needs to be verified. A modest increase in output was observed at higher doses (4 g/L to 8 g/L) throughout the first four days, with a peak around day four that was less than the 2 g/L concentration. All things considered, a starting point of about 2 g/L yeast extract and a fermentation period of 3 to 4 days seems promising for effective ethanol generation from potato peels employing S. cerevisiae. In another study by [

5], optimal conditions for bioethanol production from PPW using four yeast isolates were investigated. A particular method, called Separate Hydrolysis and Fermentation (SHF), breaks down the starch into sugars first (a process known as hydrolysis), and then ferments those sugars to produce ethanol. Various temperatures, pH values, and incubation durations were looked into in the experiment. After 72 hours of incubation and at 35°C and pH 6.0, the greatest bioethanol output was obtained, effectively completing the cycle from PPW back to a fuel source. Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF), which integrates these processes into a single operation and may save both time and resources, was another investigated technique. Two yeast strains (YPO3 and YPmp3) that performed well in the identical SHF ideal circumstances (35°C, pH 6.0, 72 hours) were found by the study [

6].

2.2. Carrot Pomace (Daucus carota subsp. sativus)

Carrot pulp waste contains sugars, specifically fructose of 5.4%, sucrose of 14.3%, and glucose of 7.9% on a dry weight basis [

7]. These sugars can be fermented to produce bioethanol. Carrot pomace's composition, measured in dry matter, is 28 percent cellulose, 6.7 percent hemicellulose, 2.1 percent pectin, and 17.5 percent lignin [

8]. Studies have demonstrated that by utilizing yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and fermentation, it is possible to successfully transform this sugar-rich waste into ethanol. Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, dried carrot pulp, and beet molasses were used in the study to attain a maximum ethanol concentration of 40.63 g/L (4.06% w/w) at 28°C for 72 hours. To improve sugar accessibility, the substrate preparation step of the method involves washing, air-drying, and grinding the carrot pulp. Following that, an inoculum—a sugar-water solution containing activated yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae is added to the prepared substrate. The primary step, fermentation, is keeping the mixture at a specific temperature so the yeast can ferment the sugars into ethanol. After fermentation, the produced ethanol is separated by distillation, and the yield is calculated. This measurement is essential for streamlining the procedure. Researchers can enhance the efficiency of ethanol production by modifying variables such as the amount of carrot pulp and the volume of inoculum. Feeding these adjustments back into the first step, more leftover carrot pulp can be used in later cycles. In contrast to other biofuel sources, carrot pulp currently yields a very modest amount of ethanol of around 4%. A higher ethanol production of 53.1 g/L (4.1% w/w) from unwashed pre-treatment rapeseed straw was observed in a different investigation. An additional investigation into rotting carrots produced a yield of 73.67 ml of 12.66% pure ethanol. A favourable association was seen between the volume of inoculum and ethanol production (2.5-7.7 ml) in five control samples that included only inoculum and varied in volume (0-50 ml). The ethanol production of samples with carrot pulp (5 g or 10 g) was significantly higher than that of samples without pulp (3.6-10.3 ml vs. 2.5-7.7 ml). This draws attention to the fermentable sugars in carrot pulp that aid in the synthesis of ethanol. When 10 g of pulp was used, the increase in ethanol generation was most noticeable, showing a 51% increase over the control sample with the largest inoculum volume. Gas generation per day was tracked in samples that contained and did not contain carrot pulp. Daily gas production was monitored in samples with and without carrot pulp. The sample containing pulp exhibited a higher and earlier peak in gas production (1390.1 cm

3 on day 2) compared to the control (423.89 cm

3 on day 3). Another study explored by (Nawirska et al., 2005) talks about how Carrot pomace is converted to bioethanol using independent procedures for fermentation and hydrolysis like SHF. Then the pomace is pre-treated to let go of the trapped fermented sugar. Here, pectinase and AccelleraseTM 1000 enzymes are added and left for 84 hours at 50°C. Kluyveromyces marxianus, a thermotolerant yeast, is introduced in a single step. The pre-treated pomace's released sugars are consumed by the yeast, which ferments them into ethanol. Researchers used a strategy of supplementation. After the first 12 hours of fermentation, the ethanol content rose dramatically up to 37 g/L from 18 g/L besides the inclusion and integration of 10% carrot pomace. Researchers explored increasing the enzyme dosage for pre-treatment, hoping to improve sugar release. However, this approach backfired. Doubling the enzyme dose resulted in a much lower ethanol concentration (15 g/L) after 72 hours. Further investigation revealed that high enzyme doses of AccelleraseTM 1000 inhibited the development of fermenting yeast like Kluyveromyces marxianus K21.

2.3. Tomato Pomace (Solanum lycopersicum)

In the biofuel sector, waste valorization is becoming more popular, and agricultural processing wastes are becoming viable feedstocks. This study by Miriana, Durante, et al., investigates the use of tomato pomace, a processing by-product rich in polysaccharides found in tomato cell walls, as a substrate for the synthesis of bioethanol. The useful pigment lycopene is extracted using supercritical CO2 (SC-CO2), and further, it is examined how this process affects the pomace's potential for bioethanol conversion. Results from both untreated and SC-CO2-extracted pomace were encouraging. The complex polysaccharides in the pomace were effectively transformed into fermentable sugars by enzyme treatment using Driselase, untreated pomace produced 383 mg/g dry weight, while SC-CO2-extracted pomace produced 301 mg/g [

10]. The hydrolyzed sample's sugar content is subsequently determined using advanced and powerful anion exchange chromatography with a detector (HPAEC-PAD). Concurrently, an independent stream of examination concentrates on the pomace's cell wall composition. Here, different polysaccharide fractions are isolated and their composition is revealed through progressive extraction using different chemicals. These fractions are thereafter exposed to analysis using methods like GC-MS or gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to pinpoint the precise connection between the sugar units inside the cell wall polysaccharides. Subsequently, experiments of fermentation with yeast cells that have been immobilized are conducted. Fermentation is applied to the tomato serum (water-soluble fraction) and the sugar syrups produced by enzymatic hydrolysis. This stage tracks the amount of sugar consumed and the amount of bioethanol produced, giving important information about how fermentable the pomace material is. Interestingly, the SC-CO2 treatment didn't significantly alter the total amount of polysaccharides extracted. Both treated and untreated pomace yielded similar overall quantities of around 846 mg/g and 815 mg/g respectively [

11]. Pectins, likely extracted by a CDTA + Na2CO3 solution, remained fairly constant at roughly 37% of the cell wall material in both treated and untreated samples. Hemicelluloses, isolated using KOH extraction, showed a slight increase after SC-CO2 treatment (226.0 mg/g compared to 213.7 mg/g). The untreated pomace contained a higher proportion of α-cellulose (320.2 mg/g) compared to the treated pomace (283.9 mg/g), suggesting that SC-CO2 treatment might partially affect the cellulose content or its accessibility within the cell wall structure. Enzymatic hydrolysis successfully broke down the pomace, yielding a total sugar concentration measuring 382.9 ± 10.3 mg/g of dry weight. This sugar pool is a mix of various types, with glucose being the most abundant at 40.5 ± 1.2 mol %, followed by fructose (22.6 ± 2.1 mol %) and other sugars like rhamnose, arabinose, and galactose present in smaller quantities. The analysis also identified disaccharides like isoprimeverose, xylobiose, and cellobiose. This detailed sugar profile, along with fermentation tests achieving over 60% of the theoretical bioethanol yield, paints a promising picture for utilizing tomato pomace as a bioethanol feedstock. In a different study by (Lenucci et al., 2013), a separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF) process was employed. Rotten tomatoes were first dissolved in water, pH adjusted, and autoclaved. Next, the tomato material was broken down using a commercially available Aspergillus niger cellulase enzyme. The resulting hydrolysate, rich in sugars, was then fermented using baker's yeast. To determine the best configuration for producing bioethanol, the researchers experimented with various fermentation settings. Temperature of around 20, 25, and 30°C and an incubation duration of 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 144 hours were among the variables they changed [

13]. It turned out that 30°C and a 24-hour incubation period were the ideal parameters for the production of bioethanol. The highest possible bioethanol production rate of 0.17% (v/v) was obtained under these circumstances [

14].

2.4. Brinjal (Eggplant) Peels (Solanum melongena)

Eggplant peel emerges as a promising candidate for a two-stage biorefinery method. The study by (Demiray et al., 2024) explored the potential for valuable anthocyanin extraction followed by bioethanol production. In the first stage, the focus was on maximizing anthocyanin yield. The study explored the impact of different solvents on the extraction performance. Among the tested options, a 50/50% ethanol-water solution yielded the highest anthocyanin concentration (2306.1 ± 3.5 mg/kg) when used with 20% (w/v) eggplant peel [

15]. The remaining lignocellulosic residue after anthocyanin extraction served as the feedstock for bioethanol production in the second stage. Here, enzymatic hydrolysis breaks down the carbohydrates into fermentable sugars, followed by fermentation using yeast to produce bioethanol. The impact of initial eggplant peel loading on bioethanol yield was also further examined. The results showed that a 15% peel loading achieved the most favorable outcome. Under these conditions, Saccharomyces cerevisiae produced a maximum Ethanol content of 27.5 g/L and volumetric ethanol biofuel productivity of 0.76 g/Lh. Kluyveromyces marxianus also performed well, reaching a maximum of 26.6 g/L of ethanol and 0.74 g/L of volumetric productivity. Additionally, hypothetical ethanol yields were computed, and they came out to be 89.6% in S. cerevisiae as well as 86.8% in K. marxianus. Further optimization of the process, such as refining the enzymatic hydrolysis step, could lead to even greater efficiency in bioethanol production from eggplant peel [

16].

2.5. Radish Leaves (Raphanus sativus)

Radish leaves are a common member of the Brassicaceae family thriving in temperate climates, and possess a rich nutritional profile including carbohydrates, sugars, and vitamins [

17]. In a study by (Andrade et al., 2012), a potential feedstock using the synthesis of bioethanol was examined for this agricultural waste. It was mainly focused on the fermentable sugar content of radish leaves and their conversion efficiency into bioethanol. The researchers employed distilled water extraction to isolate carbohydrates from radish leaves. After the sugars were extracted, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly called baker's yeast, was used to ferment them in anaerobic circumstances for bioethanol production. Specific chemicals that were involved during the process of fermentation confirmed the successful generation of bioethanol [

19]. The leaves of radish were soaked for a week in distilled water (15.5 L) to extract fermentable sugars. The longer soaking period (three days) of radish leaves in comparison to other vegetable peels may indicate a more intricate cell wall construction in the leaves, which would impede the availability of carbohydrates. For the radish leaves, the researchers used a two-step filtration procedure after the soaking time. They first separated the material using cotton cloth and then used Whatman filter paper for a more thorough filtration. The radish leaf extract may contain larger particles or suspended materials than other vegetable peel extract, necessitating the need for this multi-step procedure. The hydrochloric and salicylic acids were combined with the fermented radish leaf extract. This starts a chemical reaction that results in the non-volatile derivative ethyl salicylate, which is formed when salicylic acid and bioethanol in the extract combine. After that, the mixture was refluxed for 12 hours at a temperature as high as 100°C [

20]. Refluxing guarantees the entire process and makes it possible for bioethanol to be efficiently converted to ethyl salicylate. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was employed to detect the presence of ethyl salicylate following reflux. Using the TLC plate, various components in the mixture are separated according to how they interact with the stationary phase and solvent. Researchers could indirectly verify the existence of bioethanol by comparing the position (Rf value) of the sample extract with a standard sample of ethyl salicylate. To separate the carbohydrates and other polar components from the radish leaves, distilled water extraction was used. After that, the extracts underwent several biochemical assays, such as the Combur, Fehling's Solution, and Molisch tests [

21]. All of the tests produced favorable results, proving that radish leaves contain carbohydrates. The Combur Test measured the concentration of proteins (500 mg/dL) and glucose (1000 mg/dL) precisely [

22]. The radish leaf extract tested out to have a pH of 6.9, which is mildly acidic. After pre-treatment and analysis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae was then further used to ferment water extracts under partially anaerobic (low oxygen availability) conditions. The pH of the solution was determined to be 6.5 following the seven-day fermentation process. This drop in pH from the starting value of 6.9 indicates that during the conversion of carbohydrates to bioethanol, acidic by-products likely carboxylic acids are formed. The study achieved a bioethanol yield of 1.23% from radish leaves. Future studies could increase bioethanol yield by refining the fermentation process and possibly utilizing pre-treatment techniques like enzymatic hydrolysis.

2.6. Onion Peels (Allium cepa)

One waste material that is easily accessible in large amounts is onion peels, which have been studied as a possible supply of fermentable sugars for bioethanol production. The investigation used diluted sulfuric acid as an acid pre-treatment to improve the sugars' accessibility within the onion peel cell wall structure [

23]. This pre-treatment may reduce complicated carbs to simpler sugars, increasing yeast's availability for fermentation. When onion peels were used as substrate, a higher concentration (100g) produced a higher bioethanol production (26.51%) than when the concentration (50g) was used. In comparison to 0.5%, a larger concentration of yeast inoculum (1%) produced a better yield of bioethanol [

24]. This implies that more carbohydrates can be converted into bioethanol by a larger population of yeast. One waste material that is easily accessible in large amounts is onion peels, these potential sources and origin of fermentable sugars for bioethanol production have been explored. The investigation used diluted sulfuric acid as an acid pre-treatment to improve the sugars' accessibility within the onion peel cell wall structure. This pre-treatment may reduce complicated carbs to simpler sugars, increasing yeast's availability for fermentation. When onion peels were used as substrate, a higher concentration (100g) produced a higher bioethanol production (26.51%) than when the concentration (50g) was used. In comparison to 0.5%, a larger concentration of yeast inoculum (1%) produced a better yield of bioethanol. This implies that more carbohydrates can be converted into bioethanol by a larger population of yeast. Acid hydrolysis, a technique to break down complex carbohydrates, was employed to improve the accessibility of sugars within the onion peels. Dilute sulfuric acid (1.5%) was used for this pre-treatment for this pre-treatment. Onion peel waste samples (ground into a fine powder) were soaked entirely in this dilute acid solution for 15 minutes at 121°C in an autoclave (a pressurized chamber used for sterilization). Two different onion peel waste concentrations were tested, 50 grams and 100 grams. The amount of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) added to the fermentation process was varied, with either 0.5% or 1% inoculum used. Each substrate concentration and yeast inoculum combination were tested in triplicate (three repetitions) to ensure data accuracy. Yeast was added to the pre-treated onion peels, and they underwent incubation for 12 days at 30°C. The fermentation combination received a nutrient supplement to aid in the growth of the yeast. The pH of the solution was raised to 4.5, the ideal level for yeast activity. Samples were collected every 4 days to monitor bioethanol production and other parameters like reducing sugar concentration and cell density [

25]. A functional group classification test was used in the course of research to verify that alcohol was present in the distillate, the end product. In this test, a sample is treated with concentrated sulfuric acid, and the sample's colour is monitored. When an orange-red colour shifts to a green or blue hue, it suggests the presence of primary or secondary alcohol, in this example, bioethanol. The acidified dichromate titration method was employed by researchers to measure the yield of bioethanol. The fermented broth is distilled using this procedure, and the distillate is then treated with a potassium dichromate solution. After measuring the amount of dichromate that is still present, the amount of bioethanol is computed from the reaction that takes place. A spectrophotometer was used to quantify cell density, which is a metric of yeast growth, at a particular wavelength (600 nm). To verify cell density, a dry-weight approach was also used. With this procedure, the yeast cells are separated from the broth, their wet weight is measured, they are dried, and their dry weight is measured. The study employed statistical analysis (ANOVA) to assess the significance of various factors on bioethanol production. The Least Significant Difference (LSD) test to compare treatment means and identify significant differences between specific groups was also used. This study successfully converted onion peels into bioethanol fuel, demonstrating their potential as a sustainable feedstock.

2.7. Pumpkin Peels (Cucurbita pepo)

The study of dried pumpkin peel wastes reveals a rich composition, with total carbohydrates dominating, followed by fibre, water, proteins, and ash. Pumpkin peels have a low lipid level, which makes them a desirable supply for a variety of applications [

26]. In addition, the high starch content of 65.30 percent dry matter makes pumpkin peels an excellent source of glucose, confirmed by research on sorghum grains [

27]. Pumpkin wastes are a great source of carotenoid pigments and have a high starch content, 60% of dry mass is starch. The four processes of saccharification, fermentation, distillation, and physicochemical pre-treatment can convert starchy biomass into bioethanol. The waste goes through a rigorous process that includes air drying, crushing into a fine powder, and hot-water washing to remove contaminants. By employing the Response Surface Methodologies (RSM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), two different procedures and techniques to modelling, researchers sought to optimize both the reduction of sugar content and the production of bioethanol [

28]. Notably, they utilized a central composite rotating layout which identifies the ideal circumstances for enhancing the production amount of both sugar and bioethanol. The study discovered that when it came to estimating and predicting these results, ANN outperformed RSM. The ideal parameters for the hydrolysis process, as predicted by the artificial neural network were a 120-minute hydrolysis period using a 17.5 g/L substrate loading, 7.5 U/g of α-amylase, and 56.40 U/mL of amyloglucosidase concentration [

29]. The ideal parameters for the fermentation process were 45 °C for the temperature, 5.06 for the pH, 188.5 rpm for the shaking speed, and 1.95 g/L of yeast. With reducing sugar at 50.60 g/L and bioethanol at 84.36 g/L, respectively, experimental results closely matched the ANN predictions, compared to the projected values of 50.69 g/L and 84.27 g/L. Additionally, the study determined that the two most important variables influencing the concentrations of bioethanol and reducing sugar, respectively, were substrate loading and fermentation temperature. Through 3-D and contour plots, the interaction effects between independent variables are further clarified, revealing complex interactions between variables such as enzyme concentrations and hydrolysis time on lowering sugar concentrations. Enzymatic hydrolysis is essential to the generation of bioethanol from pumpkin peel wastes, according to a different study by (Yesmin et al., 2020 Pumpkin peels contain complex plant starches that require around 1750 units of the enzyme α-amylase to break down into simpler sugar particles termed dextrins. Enzymes like Gluco-amylase are then utilized to transform this dextrin into fermentable sugar and utilized by yeast. All of these enzymatic treatment lowers chemical expenses, streamlines starch processing, and increases the yield of ethanol produced [

30]. About 100 grams of pumpkin peel samples are mixed with 300 millilitres of distilled water to start the fermentation process. A muslin cloth is used to filter part of the mixture while leaving the other unfiltered [

31]. Subsequently, 200 millilitres of yeast and 1750 units of the enzyme α-amylase are added to the filtered and unfiltered solutions. The regulated settings for these tests are 35°C and pH 6.0 [

32]. The crude fermentation mixture is centrifuged for five minutes at 12,000 rpm following six successive days of fermentation to extract any leftover starch and cell fragments of yeast. Following that, the clear solution is heated to 78.5°C and treated to rotary evaporation to separate the ethanol. The metabolic activity of yeast facilitates this transition. Distillation equipment is utilized to carry out the distillation process at 78.5°C. The ethanol content is estimated from the condensate that is collected [

33]. With the use of an alcohol meter that can measure alcohol purity from 0% to 100%, the purity of the bioethanol produced is determined. Every treatment is carried out in triplicate as part of the data analysis process, and every outcome is presented as mean values ± standard deviation or SD. Pumpkin peel wastes can be used in the synthesis of bioethanol that guarantees the validity and consistency of the resulting experimental data through a strict methodology [

34].

Table 1.

Comparison of different varieties of Vegetables found around different parts of the world.

Table 1.

Comparison of different varieties of Vegetables found around different parts of the world.

| Vegetable Waste |

Pre-treatment Method |

Temperature (°C) |

Time (minutes) |

pH |

Enzyme |

Comments |

References |

| Potato peels |

Steam explosion |

160 |

10 |

4.5 |

Cellulase |

High starch content |

(Sheikh et al., 2016; Sujeeta et al., 2018)

|

| Carrot pomace |

Dilute acid hydrolysis followed by enzymatic hydrolysis |

110 |

45 |

2 |

Hemicellulase & Cellulase |

Fermentation: Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

(Khoshkho et al, 2022; Yu et al., 2013) |

| Tomato pomace |

Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

80 |

20 |

5.5 |

Pectinase & Cellulase |

High moisture content |

(Miriana et al., 2013) |

| Brinjal (Eggplant) peels |

Steam explosion |

150 |

12 |

4 |

Cellulase |

Moderate lignin content |

(Demiray et al., 2024) |

| Radish Leaves |

Dilute acid hydrolysis |

100 |

60 |

2.5 |

Hemicellulase & Cellulase |

Requires optimization due to low sugar content |

(Khan et al., 2015) |

| Onion peels |

Steam explosion followed by enzymatic hydrolysis |

140 |

8 |

4 |

Cellulase |

Low cellulose content |

(Genemo et al, 2021) |

| Pumpkin peels |

Steam explosion |

150 |

12 |

4.5 |

Cellulase |

Suitable for co-fermentation with other wastes |

(Chouaibi et al., 2020) |

3. Lignocellulosic Biomass

3.1. Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum)

The widely available lignocellulosic residue known as sugarcane bagasse (SCB) has gained attention for being the second-generation potential feedstock for the synthesis of bioethanol [

35]. However, due to the intricate interactions between cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, SCB is recalcitrant, which means that pre-treatment is necessary to enhance hydrolysis by enzymes and the ensuing bioethanol yields. The effectiveness of chemical and physicochemical pre-treatment techniques, such as steam explosion and acid or alkali treatment, in disintegrating the structure of cell walls, increasing cellulose's accessibility to cellulolytic enzymes, and possibly improving hemicellulose hydrolysis, has been thoroughly studied. Finding the ideal balance between maximizing sugar production, minimizing inhibitory chemicals formed from lignin, and overall process economics is crucial when choosing a pre-treatment technique. The Sugar Content of sugarcane ranges from 13-20% sucrose, its high sugar content makes it a primary source of bioethanol [

36]. The sucrose in sugarcane stalks is easily extracted and fermented by yeast to produce ethanol. Its ethanol yield amounts to 12.5% which makes it an efficient component for bioethanol production. Yeast fermentation requires a pH between 4.5 and 5. Using a group of cellulolytic enzymes, enzymatic hydrolysis breaks down cellulose into sugars that can be fermented after pre-treatment. The fermentable carbohydrates are then fermented by microorganisms, usually Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to produce ethanol. Finally, the bioethanol product is concentrated and purified using distillation processes. The primary components of SCB's complicated structure are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, is disrupted by acid pre-treatment, increasing the accessibility of the trapped sugars for ethanol conversion [

37]. The two main types of acidic pre-treatment methods are diluted acid pre-treatment and concentrated acidic pre-treatment [

38]. Low temperatures (30–60°C) are effective for concentrated acid pre-treatment with extremely concentrated acid solutions (about 40–80%). Dilute acid pre-treatment uses 0.5–6% diluted acids at temperatures between 120 and 170°C, with treatment periods varying from a few minutes to an hour [

39]. The most often utilized acid is sulfuric acid (H2SO4) because of its affordability and efficiency in the hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Though marginally less effective, phosphoric acid (H3PO4) provides a more ecologically friendly substitute. Steam explosion uses high-pressure steam to break down cell walls, while LHW or liquid hot water employs hot water for targeted hemicellulose removal. While steam explosion can require harsh conditions, LHW might yield less sugar. The optimal choice depends on factors like desired sugar yield, processing speed, and environmental impact.

3.2. Corn Stover

The corn stover employed for the experiments contained glucan (37.5%), and xylan (21.7%), along with other components like galactan, arabinan, lignin, and ash [

40]. To maximize sugar yield for bioethanol production by E. coli FBR5, this study looked into the use of diluted acid pretreatment of maize stover, which can be used to avoid the requirement for detoxification. The greatest sugar yield (63.2 ± 2.2 g/L at 0 minutes and further 63.7 ± 2.3 g/L at 5 minutes) following enzymatic hydrolysis was obtained at 0.75% H2SO4 at 160°C with a 0–5-minute holding duration, according to the researchers' comparison of pretreatment parameters (temperature, acid content, and holding time). Significantly, under these circumstances, the synthesis of furfural which is known to suppress fermenting microbes was reduced (beginning at 0 minutes, 0.45 ± 0.1 g/L, and 5 minutes, 0.87 ± 0.4 g/L) [

41]. As the selected strain of E. coli, FBR5, showed tolerance to these low levels of furfural (< 0.5 g/L), fermentation was able to proceed without the need for a detoxifying phase [

42]. This method, which uses a tolerant strain of E. coli to produce high sugar yields can drastically reduce costs associated with processing the manufacturing of cellulosic bioethanol. To produce fermentable sugars for the manufacturing of bioethanol, this study looked into enzymatic hydrolysis and diluted acid pretreatment. The activities of xylanase, β-glucosidase, and cellulase were tested according to published methods. A reactor system, several temperature ranges (140–200°C), acid concentrations (0–1% H2SO4), and holding times (0–25 min) were used to optimize the pretreatment conditions. A combination of β-glucosidase and cellulase was used for enzymatic hydrolysis; xylanase was not used in the fermentation trials. The recombinant strain FBR5 of E. coli was used for fermentation. This strain was cultured in flasks using LB broth and kept in a semi-anaerobic environment. The E. coli culture then fermented the hydrolysate of pretreated maize stover (without detoxifying) to create ethanol. The salient feature of this situation is that the E. Col strain (FBR5) is selected especially because of its ability to withstand low concentrations of furfural, a fermentation inhibitor produced during pretreatment, which in this case was less than 0.5 g/L. Due to this tolerance, there is no longer a need for an additional detoxification stage prior to fermentation, which could lower processing costs overall. The corn stover has normal concentrations of xylan (21.7%), glucan (37.5%), and other ingredients. Higher acid concentrations and temperatures often resulted in higher glucose and xylose release; at 180°C with 1% H2SO4, glucose release peaked at 10.9 g/L [

43]. But these more severe circumstances also resulted in a higher production of the fermentation inhibitor furfural. A satisfactory equilibrium between the release of sugar and the fermentation inhibitor furfural production was established by a diluted acid pretreatment at 160°C for 0 minutes with 0.75% (v/v) H2SO4. Even without eliminating fermentation inhibitors, the modified E. coli FBR5 efficiently converted sugars from the hydrolysate of pretreated maize stover into ethanol at pH 6.5. During fermentation, FBR5 converted another inhibitor, furfural, into the less harmful furfuryl alcohol. With this method, there may be a way to produce biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass without having to do the additional detoxification phase [

44].

3.3. Switchgrass

Switchgrass, a versatile native North American perennial grass, emerges as an appealing crop for bioenergy owing to its significant production of biomass and minimal input requirements. This translates to environmental benefits like carbon sequestration and improved soil health [

45]. Switchgrass, a fast-growing perennial, is emerging as a viable alternative for the paper & pulp sector. Due to its minimal lignin concentration and its capacity to be cultivated with no yearly replanting, Switchgrass is a sustainable and environmentally favourable choice. Beyond its eco-friendly profile, switchgrass is particularly attractive for bioethanol production. However, to efficiently convert switchgrass into this renewable fuel the plant's thick cell walls must be broken down in a pre-treatment stage to improve the extraction of sugar [

46]. Studies have indicated that there is significant potential for its conversion to bioethanol. Fermentable sugar yields, such as xylose and glucose, can vary after pre-treatment between 70% to 100%, resulting in ethanol yields that can reach up to 92% of the theoretical maximum. Switchgrass exhibits potential for value-added uses such as gasification, the generation of bio-oil, and even as a reinforcing material in bio-composites, in addition to biofuels. An essential first step in turning switchgrass into bioethanol is physical pretreatment. To facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis, which turns cellulose into fermentable sugars, it attempts to dissolve the plant material's strong cell walls. Switchgrass is reduced in size via mechanical means. This increases mass and heat transfer during hydrolysis, raises the surface and interfacial area and reduces the cellulose fibres' crystallinity available for enzyme action. There's an optimal particle size range (typically 0.2-2 mm) for efficient processing [

47]. Very small particles can lead to excessive carbohydrate loss, reducing final bioethanol yield. Higher moisture content in switchgrass increases the energy required for size reduction. Studies suggest using shear stress for size reduction as it's less affected by moisture content compared to tensile stress. A promising method that breaks down the stiff fibres and increases sugar yields after enzymatic hydrolysis is the combination of microwave and alkali solution treatment. Researchers have determined the ideal circumstances for using this technique. Although biological pretreatment, which uses microorganisms, offers an environmentally acceptable method, commercial switchgrass applications are now unfeasible due to its slow speed. The next stage following pretreatment is called enzymatic hydrolysis, which uses enzymes to change fermentable sugars by converting cellulose and hemicellulose. This approach is thought to be more environmentally friendly than harsh chemical treatments. With its strong yields and potential for sustainability, switchgrass is a viable option for pulp and paper, but it also has drawbacks related to fibre homogeneity and hemicellulose utilization.

Table 2.

Comparison of different varieties of Lignocellulosic Biomass found around different parts of the world.

Table 2.

Comparison of different varieties of Lignocellulosic Biomass found around different parts of the world.

| Feedstock |

Pre-treatment Method |

Temperature (°C) |

Time (hours) |

pH |

Enzyme(s) |

Comments |

References |

| Sugarcane Bagasse |

Steam Explosion |

160 - 190 |

1 - 10 |

Nil |

Cellulase |

- Disrupts lignocellulosic structure for better enzyme accessibility.

- Optimize steam pressure and residence time for efficient breakdown. |

(Sabiha et al., 2018) |

| Corn Stover |

Dilute Acid Pre-treatment |

90 - 130 |

30 - 60 |

1.0 - 2.0 |

Cellulase, hemicellulase |

- Similar to fruit peels, minimize sugar degradation and by-product formation.

- May require additional enzymes to break down hemicellulose depending on process design. |

(Riansa et al., 2011) |

| Switchgrass |

Ammonia Fiber Expansion (AFEX) |

30 - 100 |

0.5 - 3 |

Nil |

Cellulase, xylanase |

- Uses ammonia to swell the biomass and increase enzyme accessibility.

- Requires proper ammonia recovery and wastewater treatment. |

(Keshwani et al., 2007) |

| Wood Chips |

Enzymatic Hydrolysis |

40 - 50 |

24 - 72 |

4.8 - 5.5 |

Cellulase, xylanase |

- Optimum temperature for cellulase and xylanase activity.

- Enzyme cost can be a significant factor in process economics. |

(Silva et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2008; Vásquez et al., 2007) |

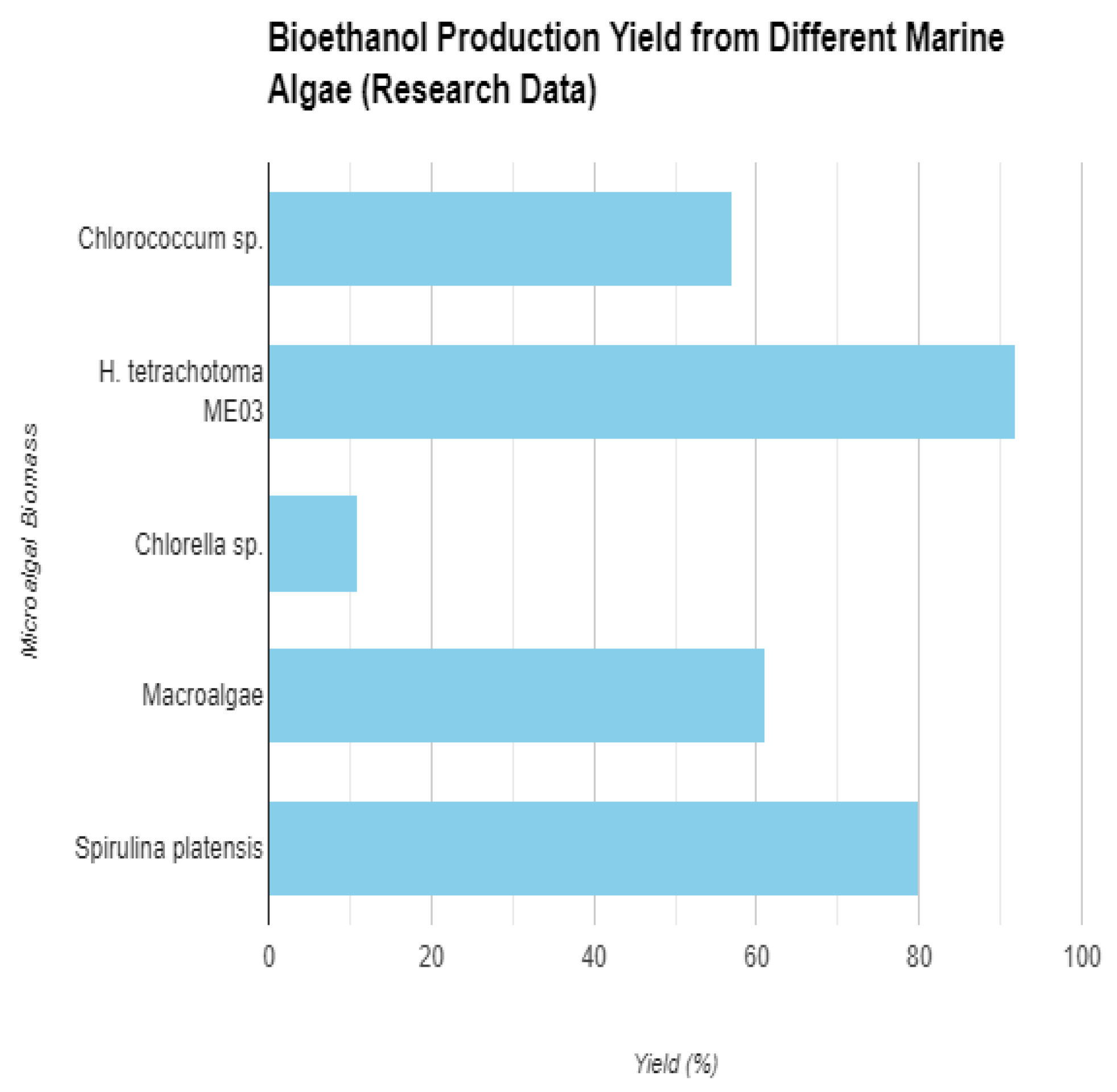

5. Marine Algae as a Promising Feedstock

Marine algae, which are divided into three categories brown, red, and green, show great promise primarily as biomass for bioethanol production because of their rapid growth plus higher carbohydrate content [

51]. Several benefits have made marine algae a potentially useful source for the production of bioethanol. Compared to conventional biofuel crops, they grow quickly and sustainably, providing a potentially renewable source of biomass [

52]. Even though they have drawbacks such as complicated cell wall architectures that require expensive pre-treatment, they are still a desirable alternative because of their potential to deliver far more ethanol than other feedstocks. Marine algae are treated using a variety of pre-treatment techniques, such as acid, microwave, and alkali treatments, to produce fermentable sugars. Enzymatic saccharification is then used to achieve efficient hydrolysis. Particularly microalgae show a significant accumulation of lipids or carbohydrates, which makes them excellent feedstocks with benefits like higher biomass yield and lack of rivalry with edible crops. Their potential as renewable sources for the manufacture of biofuel are further enhanced by their excellent conversion of CO2 and sunlight. Algae, especially macroalgae (seaweed), have a high carbohydrate content (25–60%) that can be processed to produce bioethanol. Studies suggest that bioethanol yields from algae can be significantly higher than from agricultural or forestry feedstocks – up to 60 times more. Algae can utilize carbon dioxide (CO2) during growth, potentially contributing to greenhouse gas mitigation. The cell walls of algae, especially macroalgae, contain complex carbohydrates and hydrocolloid polymers. These require pre-treatment to break them down before bioethanol conversion can occur. The pre-treatment process for breaking down the cell wall is exorbitant and this may amount to up to 20% of the entire cost of production [

53]. Macroalgae (Seaweed) are larger, multicellular algae like kelp. They are generally high in carbohydrates but require more intensive pre-treatment due to their complex cell walls. It consists of brown, red, and green macroalgae with varying sugar compositions. Microalgae are microscopic, single-celled algae. Some microalgae species have high lipid content, while others are rich in carbohydrates. Their cell walls are generally easier to break down compared to macroalgae. Promising outcomes have been obtained in studies employing several microalgae strains, such as Chlorella sp. and Chlorococcum sp., with glucose yields above 50% and bioethanol synthesis up to 11 grams per liter. Seaweed, or macroalgae, can also be hydrolyzed enzymatically; research has shown that Ulva sp. can provide ethanol yields of up to 70%. Studies using microalgae like Chlorococcum sp. yielded a glucose output of 57% [

54]. These microalgae produce bioethanol at a rate of 0.46 grams of ethanol per gram of glucose [

55]. Hindakia tetrachotoma ME03, a different microalgae strain, showed promise for producing bioethanol with a high saccharification yield of 92% [

56]. Additionally, Chlorella sp. microalgae were able to generate as much as 11 grams per liter of bioethanol using enzymatic hydrolysis [

57]. Success with macroalgae (seaweed) was also observed, with Ulva sp. achieving a 77% conversion rate into ethanol [

58]. The alginate content of Saccharina latissimi known as Sugar Kelp varies from 4.1% to around 34.5% of dry biomass occurring in late spring from April to June [

59].

Table 3.

A chart that compares the process of generating marine algae into bioethanol.

Table 3.

A chart that compares the process of generating marine algae into bioethanol.

| Microalgal Biomass |

Pre-treatment |

Enzyme |

Yield |

Source |

| Chlorococcum sp. |

Enzymatic hydrolysis |

Cellulase |

57% glucose (0.46 g/g bioethanol) |

(Shokrkar et al., 2018) |

| Hindakia tetrachotoma ME03 |

Enzymatic hydrolysis |

β-glucosidase/cellulase, α-amylase |

92% saccharification |

(Onay et a., 2019) |

| Chlorella sp. |

Hydrothermal pre-treatment, Enzymatic hydrolysis |

α-amylase, glucoamylase |

11 g/L bioethanol |

(Ngamsirisomsakul et al., 2019) |

| Macroalgal biomass (fresh river water) |

Enzymatic hydrolysis |

Cellulase enzyme |

61% bioethanol |

(Kumar et al., 2018) |

| Spirulina platensis |

None (assumed) |

α-amylase, amyloglucosidase |

80% polysaccharide conversion |

(Rempel et al., 2019) |

Figure 1.

Bioethanol yield from different Marine algae.

Figure 1.

Bioethanol yield from different Marine algae.

Table 4.

Comparison of different types of Marine Algae.

Table 4.

Comparison of different types of Marine Algae.

| Algae Type |

Pre-treatment Method |

Disruption Type |

Temperature (°C) |

Time (minutes) |

pH |

Notes for Bioethanol Production |

References |

| Green Algae (e.g., Chlorella sp.) |

Bead milling |

Mechanical |

20-30 |

5-10 |

Neutral |

Disrupts cell wall for better sugar release during bioethanol production. |

(Yadav et al., 2020) |

| Brown Algae (e.g., Saccharina sp.) |

Dilute acid hydrolysis |

Chemical |

90-100 |

30-60 |

1-2 |

Break down complex carbohydrates to fermentable sugars for bioethanol production. |

(Brown et al., 2024) |

| Red Algae (e.g., Gracilaria sp.) |

Alkali pre-treatment |

Chemical |

30-40 |

30-60 |

10-12 |

Removes hemicellulose, improving access to carbohydrates for bioethanol production. |

(Sehar et al., 2022) |

| Various Algae |

Enzymatic hydrolysis (or other enzymatic methods) |

Enzymatic |

40-50 |

60-120 |

4.5-5.0 |

Breaks down cellulose and alginate for efficient conversion to fermentable sugars in bioethanol production. |

(Jutakridsada et al., 2019) |

5. Selection of Appropriate Kinetic Models for Optimizing Bioethanol Production from Diverse Feedstocks

5.1. Michaelis-Menten (MM) Model

The most popular model for researching processes mediated by enzymes. In a homogeneous system with easy interactions between the substrate and enzyme, it is assumed [

60]. It offers a solid foundation for comprehending the kinetics of enzymes. It is simple to use, with parameters like the Maximum rate of reaction (Vmax) and Michaelis constant or Km indicated. It doesn't take into consideration factors like product inhibition, enzyme deactivation, or diffusion restrictions in heterogeneous systems (cellulose is a solid substrate). This model describes the enzymatic breakdown of a substrate (S) by an enzyme (E) to form a product (P).

Reaction includes: E + S <=> ES -> E + P

Here, the reaction rate (V); Vmax is called the maximum reaction rate and Michaelis constant is Km (concentration of substrate within the half-maximum rate).

5.2. Semi-Mechanistic Model

It provides a more comprehensive representation than the pseudo-first-order model by taking into account the many stages of cellulose breakdown (similar to the process that turns cellulose into cellobiose, which then turns into glucose). It requires fewer experimental data than completely mechanistic models. It takes into account intermediary processes to give a better grasp of the entire process. It helps streamline the hydrolysis process when concentrating on particular stages. It may not be as precise as completely mechanistic models, and the degree of information provided varies based on the model in question [

60]. This model depicts a more detailed process with multiple steps. Reactions include

i.) Cellulose + Enzyme -> Enzyme-Cellulose Complex

ii.) Enzyme-Cellulose Complex -> Glucose + Enzyme

This is when the result of the first reaction that has its own reaction which in turn gives a product of its own. The model would involve a system of differential equations representing the change in concentration of cellulose, enzyme-cellulose complex, and product (glucose) over time.

5.3. Pseudo-First Order Model

This is a simple model used for homogeneous systems (uniform mixing of reactants) where the rate of reaction depends only on the reactant concentration (cellulose in this case) [

60]. It is easy to understand and use due to its linear relationship between concentration and time. Useful for initial reaction rates when the concentration of the product is low and doesn't significantly affect the reaction rate. It doesn't account for complex reaction mechanisms or product inhibition, which become important factors later in the hydrolysis process. This model describes a simple reaction where the rate depends solely on the concentration of the reactant (cellulose, denoted as [A]).

Reaction includes: A -> Products

5.4. Model Development for Delignification

It focuses on the rate at which lignocellulose is converted into products such as glucose. When building reactors for the delignification process, this model is quite helpful. It is useful for process design and optimization since it aids in the prediction of delignification efficiency under various situations [

60]. It might not offer comprehensive details regarding the cellulose degradation process or the dynamics of enzyme activity. This model focuses on the overall conversion of lignocellulose (denoted as LS) to products. Reaction includes

5.5. Langmuir Adsorption Model

It explains how enzymes bind (adsorb) to the surface of cellulose. Since enzymes must physically be near the substrate in order to break it down, this is an essential stage in the enzymatic hydrolysis process [

60]. It takes into account the adsorption onto the substrate, which aids in understanding the connection between the concentration of the enzyme and its availability for reaction. It assumes that there is only one layer of enzyme adsorption, even though this isn't usually the case. However, it fails to take into consideration the kinetics of enzyme migration on the surface of cellulose. This model describes the adsorption of the enzyme (E) onto the cellulose surface (S) to form a complex (ES). Reaction involves

The adsorbed enzyme concentration (Eb), the maximum adsorption capacity (Ebm), the free enzyme concentration (Ef), and the association constant (Ka).

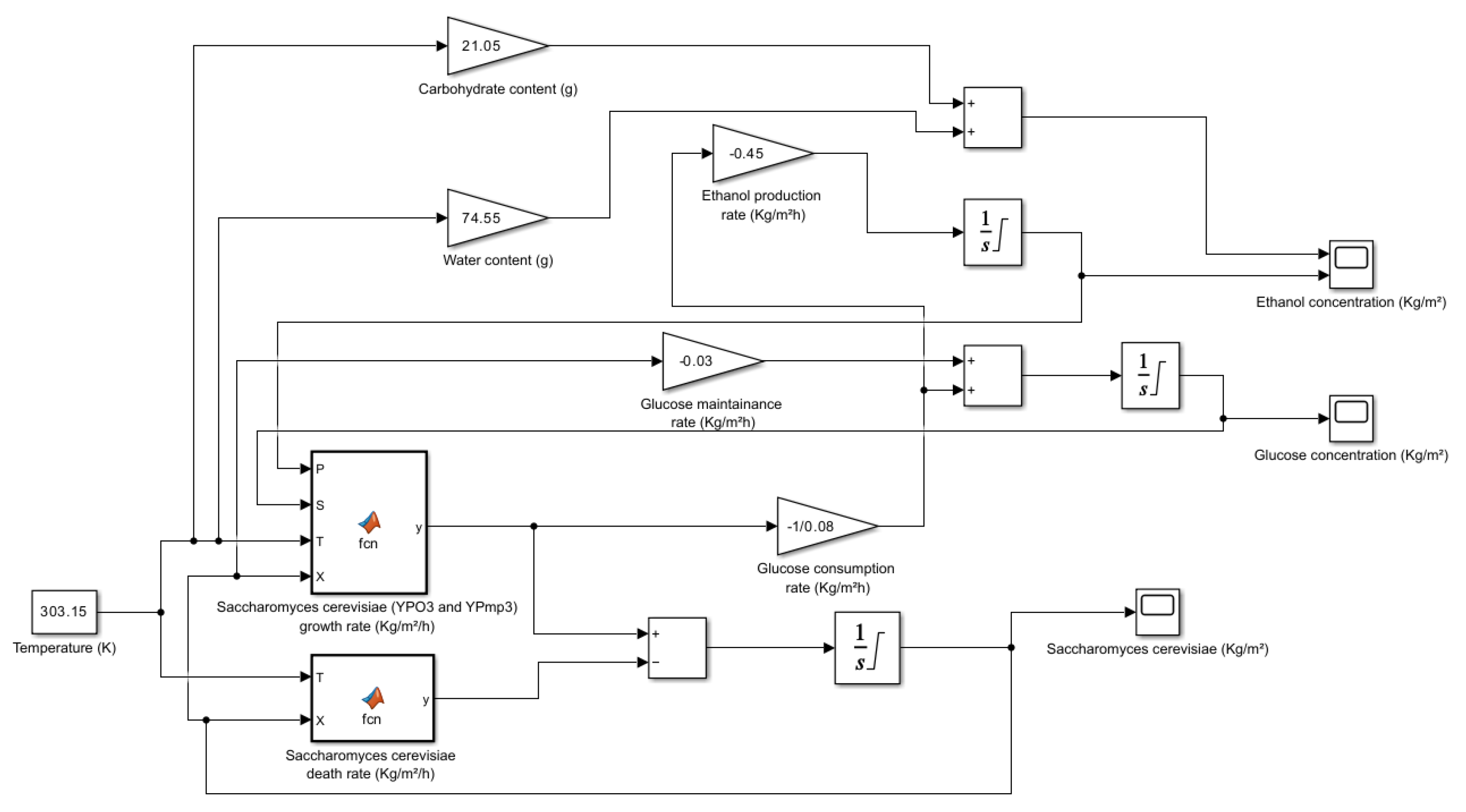

5. Kinetic and Simulation Model of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae for the Production of Bioethanol from Potato Peels, Sugarcane Bagasse and Brown Seaweed

The significant sugars and beneficial chemicals found in the residues of potato peels, sugarcane bagasse, and Saccharina latissima (sugar kelp) make them attractive substrates for microbial fermentation. The availability of fermentable sugars is necessary for the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a very common yeast that is frequently employed in commercial fermentation. Due to the mixture of simple and complex carbohydrates found in these biomass sources, pre-treatment or enzymatic hydrolysis is frequently necessary to convert polysaccharides into sugars that are easily metabolized. The Monod equation's description of the kinetics of microbial growth makes it necessary for forecasting how well these forms of substrate can be used.

The expression for the growth of microbe kinetics is as follows.

Product inhibition is a significant factor affecting fermentation efficiency. The presence of ethanol or other fermentation by-products can negatively impact microbial growth. The inhibition model,

, accounts for the reduction in growth rate as the product concentration increases. This is particularly relevant when using lignocellulosic substrates like sugarcane bagasse, as fermentation by-products such as furfural and acetic acid can act as inhibitors. Additionally, the maintenance coefficient (m) must be considered, as some substrates may require higher energy expenditure for microbial metabolism, affecting overall biomass yield. The Monod-type expression,

, describes how the yeast growth rate depends on substrate concentration. In fermentation, a lower half-saturation constant (Ks) indicates a stronger affinity of yeast for a given substrate. For example, sugar kelp contains both free sugars and complex polysaccharides like alginate and fucoidan, which may require additional enzymatic hydrolysis before yeast can efficiently utilize them. Similarly, sugarcane bagasse, being rich in lignocellulose, necessitates pre-treatment steps such as acid hydrolysis or enzymatic saccharification to release fermentable sugars. The expressions for substrate consumption and product creation kinetics are critical to understanding microbial growth processes. The kinetics of substrate consumption can be derived and written as follows.

In this case,

symbolizes the biomass yield coefficient from the substrate, while the energy cost of sustaining the microbial population during growth is taken into consideration by the maintenance coefficient, m. The product formation kinetics has the expression:

In this equation,

denotes the yield of product from substrate. Higher temperatures typically result in higher reaction rates because they cause more molecular collisions allowing enzymes and substrates to interact more frequently. The maximum specific growth rate can be represented as follows, also reflects this effect.

At ideal temperatures at about 30°C for fermentation operations, microbes like Saccharomyces cerevisiae grow more quickly, as indicated by the tendency for

to increase with temperature.

5.1. Overview of the Simulation Model

The development of a simulation model for predicting the dynamics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae -mediated microbial fermentation is described in this section. Numerous kinetic and process parameters that affect substrate consumption and product production are included in the model. One important kinetic parameter in the model is the Half-Saturation Constant (), which has a value of 1.7 kg/m3. The substrate concentration at which the microorganism's growth rate drops to half of its maximal value is indicated by this metric. A lower value shows the microorganism's stronger affinity for the substrate, in this case glucose. With a value of 93 kg/m3, the Maximum Product Concentration () is an important model parameter. This figure acts as a crucial modelling restriction and indicates the maximum product concentration that can be achieved during the process of fermentation.

The efficiency of converting substrates into biomass and product is determined by the Yield Coefficients, and . With a value of 0.08 for 0.08 kg of biomass is created for every kg of substrate that is consumed. Likewise, has a value of 0.45, meaning that for every kilogram of substrate consumed 0.45 kilograms of product are created. Predicting the overall productivity of the fermentation process requires the use of these coefficients. The energy necessary by microbial cells to sustain their fundamental operations in non-growing environments is measured by a metric called the Maintenance Coefficient (m). It shows the rate of energy consumption per unit of biomass and has an approximate value of

The rate at which microbiological viability declines over time is indicated by the temperature-dependent Decay Rate Constant (kd). The = 12.108 exp is its expression, where T is the Kelvin fermentation temperature. Since greater thermal stress speeds up cell death, a higher temperature results in a faster rate of decay. One measure that characterizes the connection between substrate concentration and substrate consumption rate is the Order of Reaction (n). A non-linear connection is shown by a value of 0.52, which means that as substrate concentration rises, the rate of substrate consumption rises less proportionately. The overall kinetics of the fermentation process and the yield of the finished product can be impacted by this.

The simulation's starting conditions are specified by the process parameters. The beginning point for microbial development is established by the initial concentration of 1.5 kg/m3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. For the purpose of calculating growth rates and product generation, the initial glucose concentration is 220 kg/m3. Overall fermentation efficiency is influenced by kinetic factors and microbial activity, which are both impacted by the fermentation temperature of 30 °C.

Table 5.

Parameters considered for building the model.

Table 5.

Parameters considered for building the model.

| Parameter |

Expression |

Description |

| Microbial Growth Rate |

|

Rate of change of biomass concentration |

| Substrate Consumption Rate |

|

Rate of change of substrate concentration |

| Product Formation Rate |

|

Rate of change of product concentration |

Table 6.

Values of the other Parameters considered.

Table 6.

Values of the other Parameters considered.

| Parameter |

Value |

|

1.7 kg/m³ |

|

93 kg/m³ |

| n |

0.52 |

|

12.108 exp

|

| m |

0.03 h−1 |

|

0.08 |

|

0.45 |

| Initial concentration of Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

1.5 kg/m³ |

| Initial concentration of glucose |

220 kg/m³ |

| Fermentation temperature |

30 °C |

Table 7.

Three diverse fruits and its various criteria.

Table 7.

Three diverse fruits and its various criteria.

| Fruit |

Content (grams/100g) |

Method of Measurement |

Other Notable Components |

**Potential Sources |

| Potato Peels (Raw) |

11.1 |

HPLC |

Dietary fiber, phenolic compounds, Vitamin C, potassium, iron, antioxidants |

USDA FoodData Central, Healthline, WebMD |

| Sugarcane Bagasse (Dried) |

15.8 |

HPLC |

Lignocellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, trace minerals |

USDA FoodData Central, Healthline, WebMD |

| Saccharina latissima (Sugar Kelp, Dried) |

11.4 |

HPLC |

Iodine, fucoidan, alginate, polyphenols, vitamins A, C, E, K, fiber |

(Akter et al., 2024) |

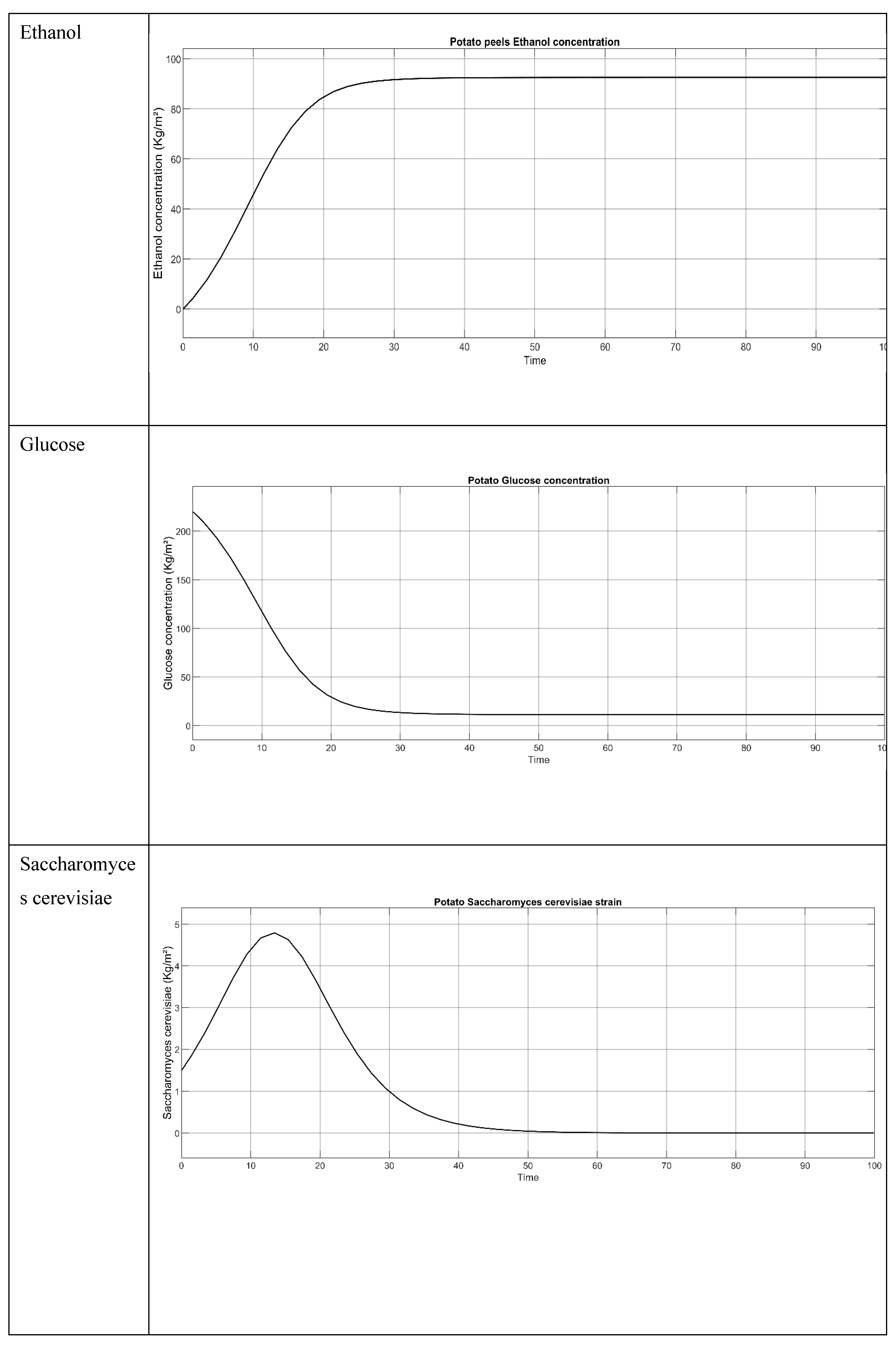

5.1.1. Potato Peels

Figure 2.

Potato Peels (Raw) simulation model when temperature is 30°C.

Figure 2.

Potato Peels (Raw) simulation model when temperature is 30°C.

Figure 3.

Result of the potato peel when all the 3 parameters concentration (S. cerevisiae, Glucose and Ethanol) are employed

Figure 3.

Result of the potato peel when all the 3 parameters concentration (S. cerevisiae, Glucose and Ethanol) are employed

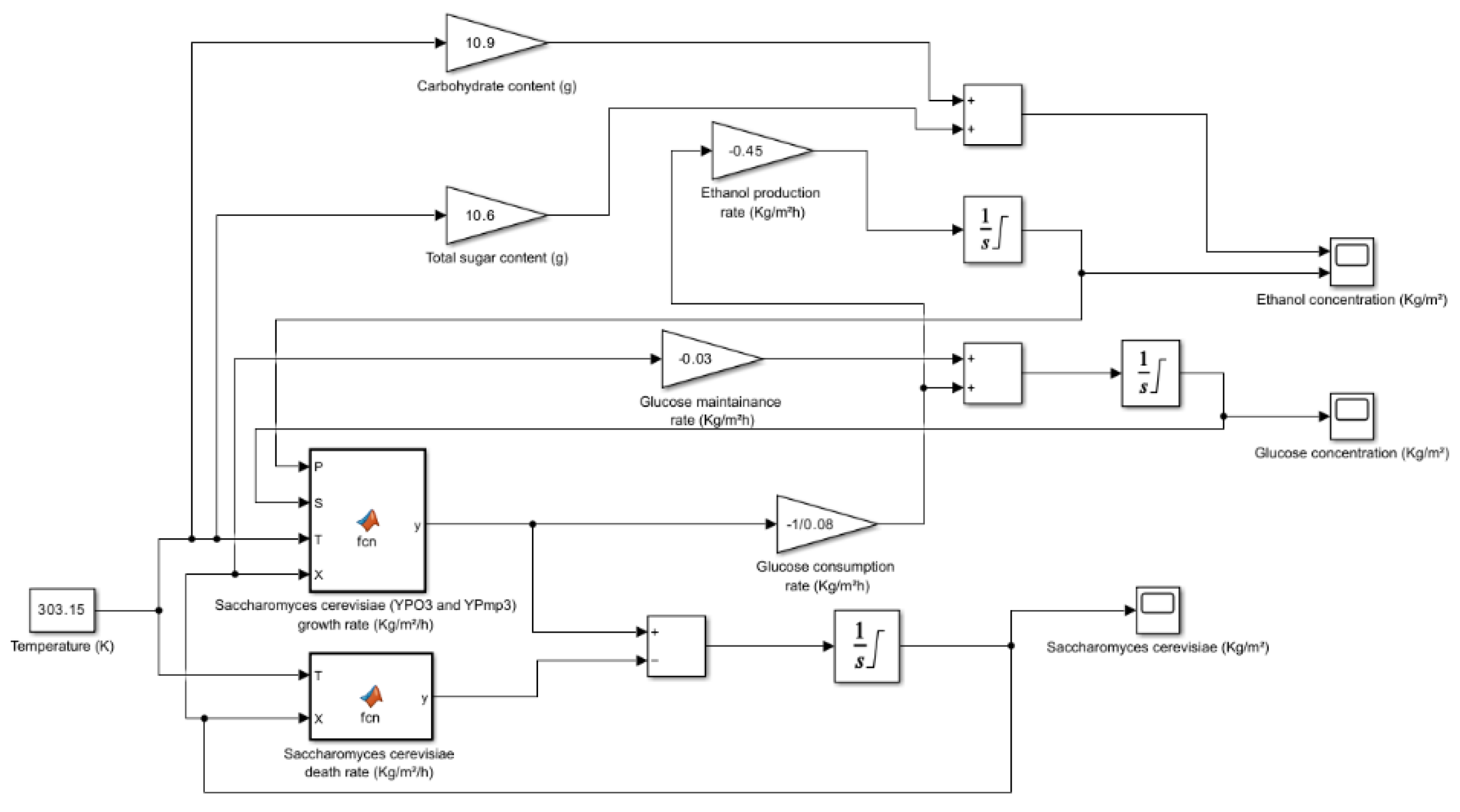

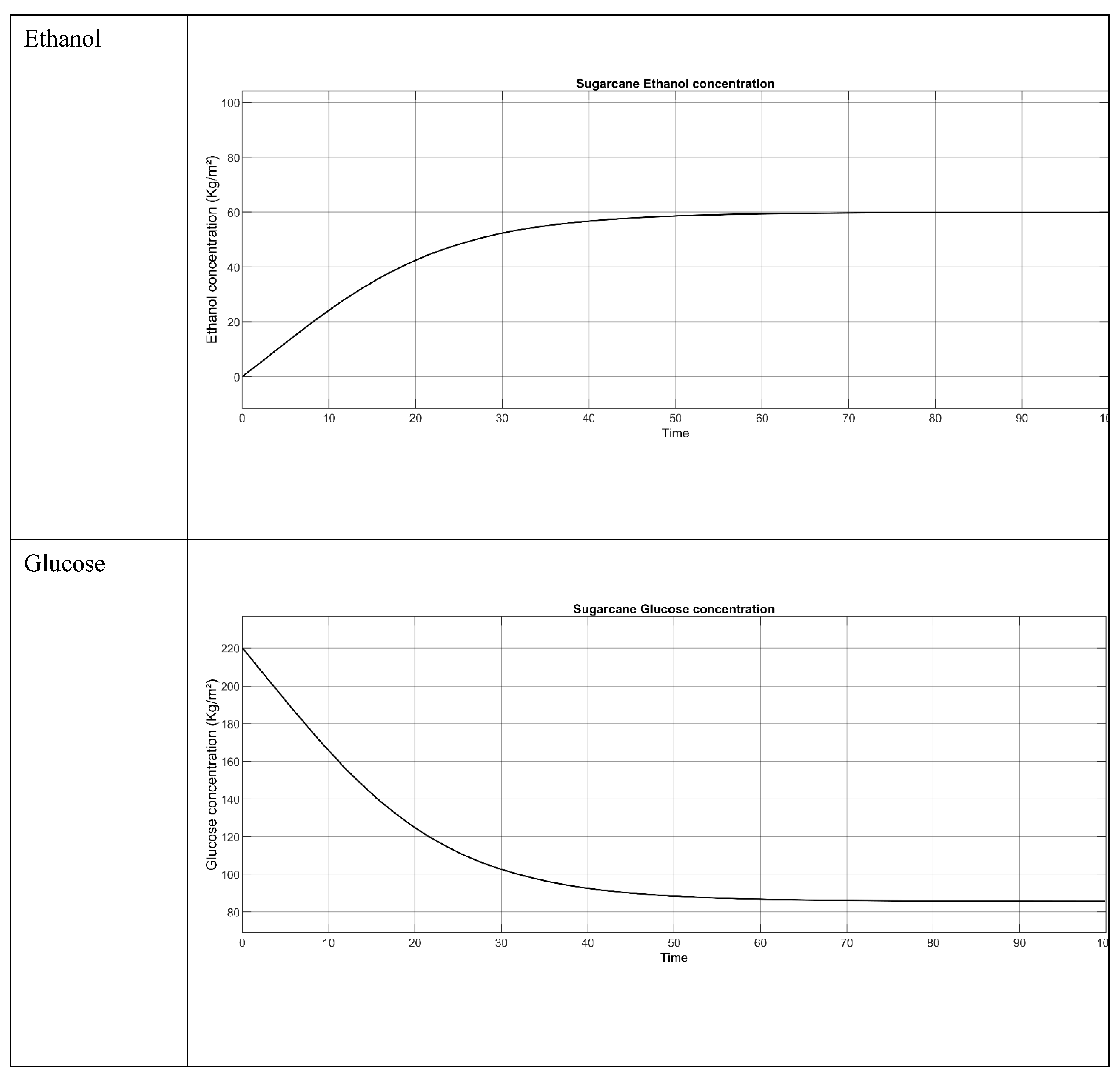

5.2.2. Sugarcane Bagasse

Figure 4.

Sugarcane Bagasse (Dried) simulation model when temperature is 30°C.

Figure 4.

Sugarcane Bagasse (Dried) simulation model when temperature is 30°C.

Figure 5.

Result of the Sugarcane bagasse when all the 3 parameters concentration (S. cerevisiae, Glucose and Ethanol) are employed.

Figure 5.

Result of the Sugarcane bagasse when all the 3 parameters concentration (S. cerevisiae, Glucose and Ethanol) are employed.

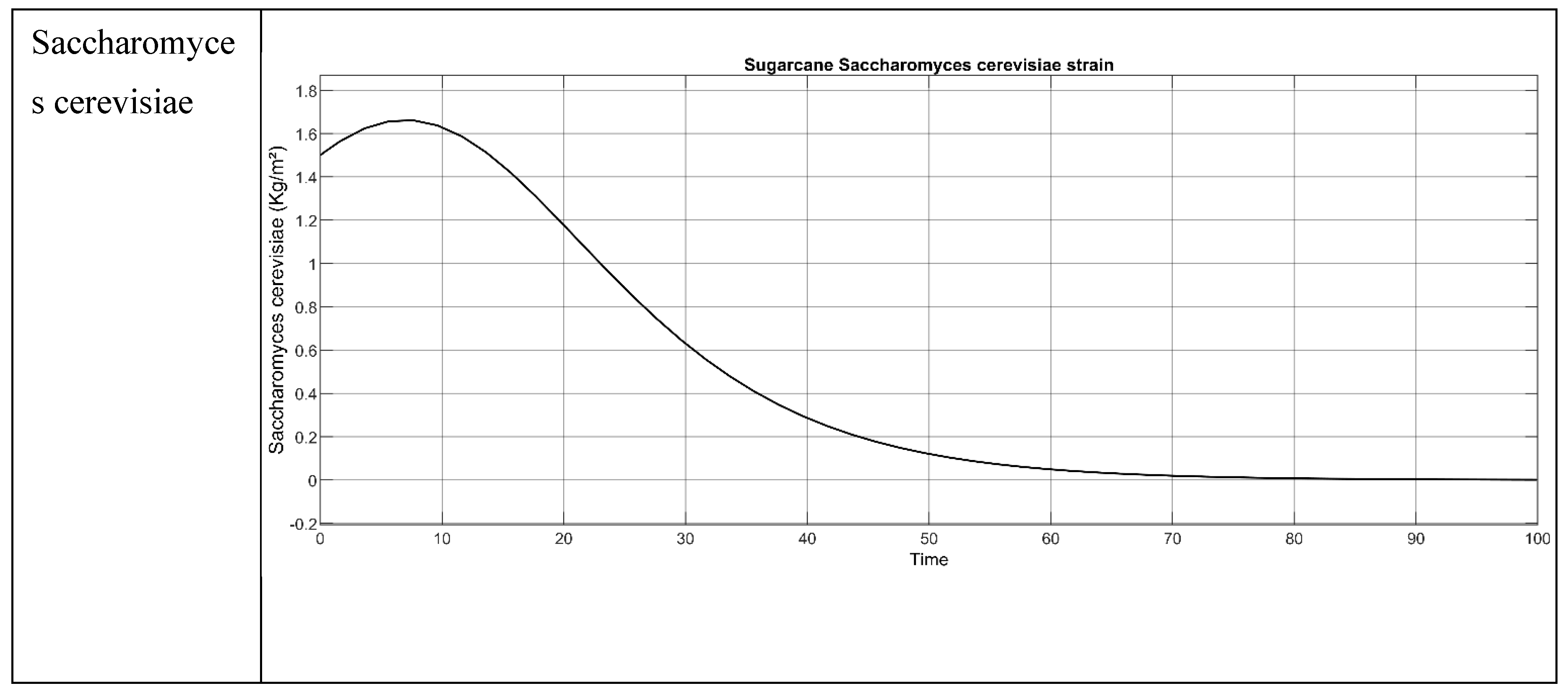

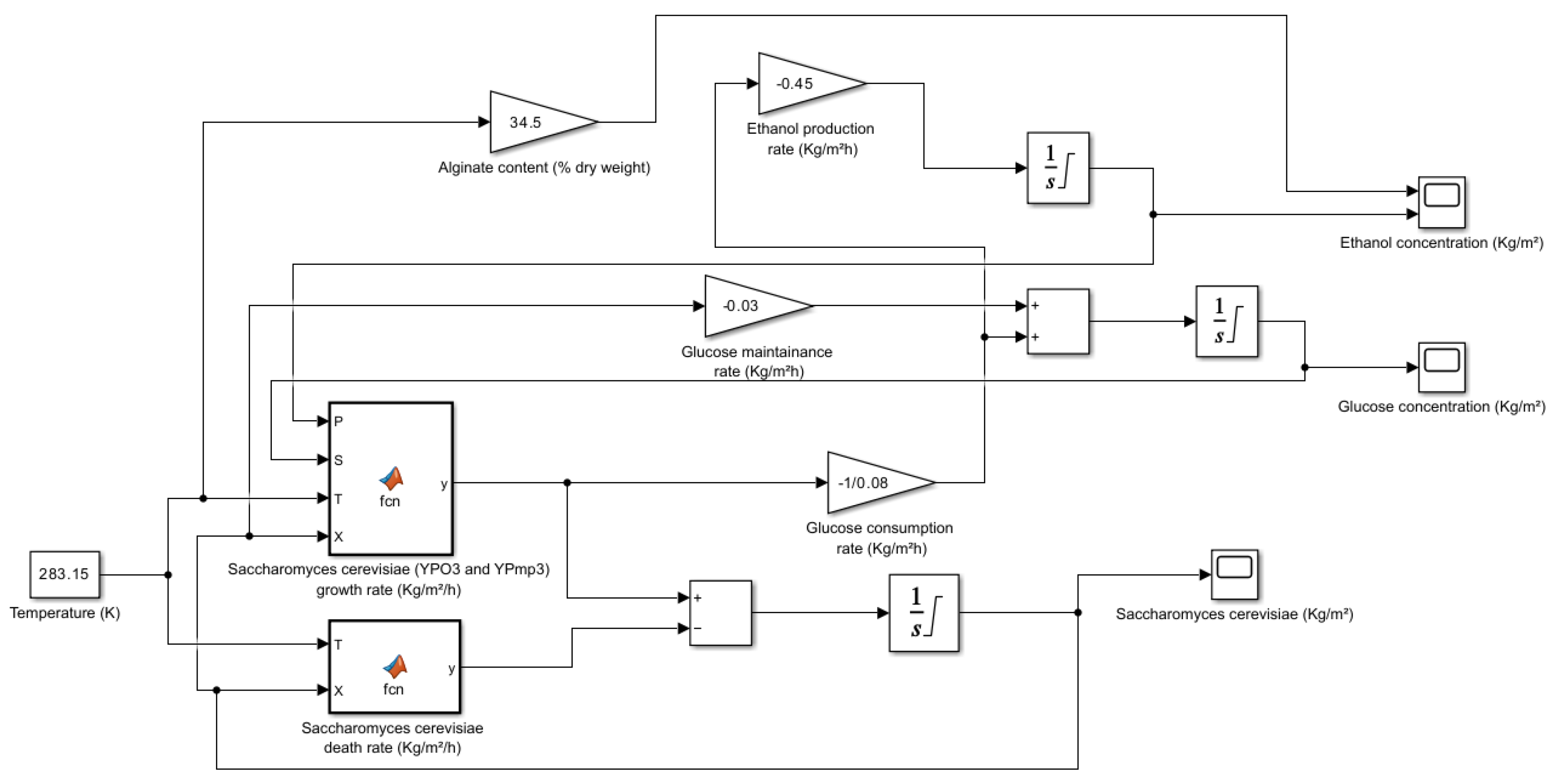

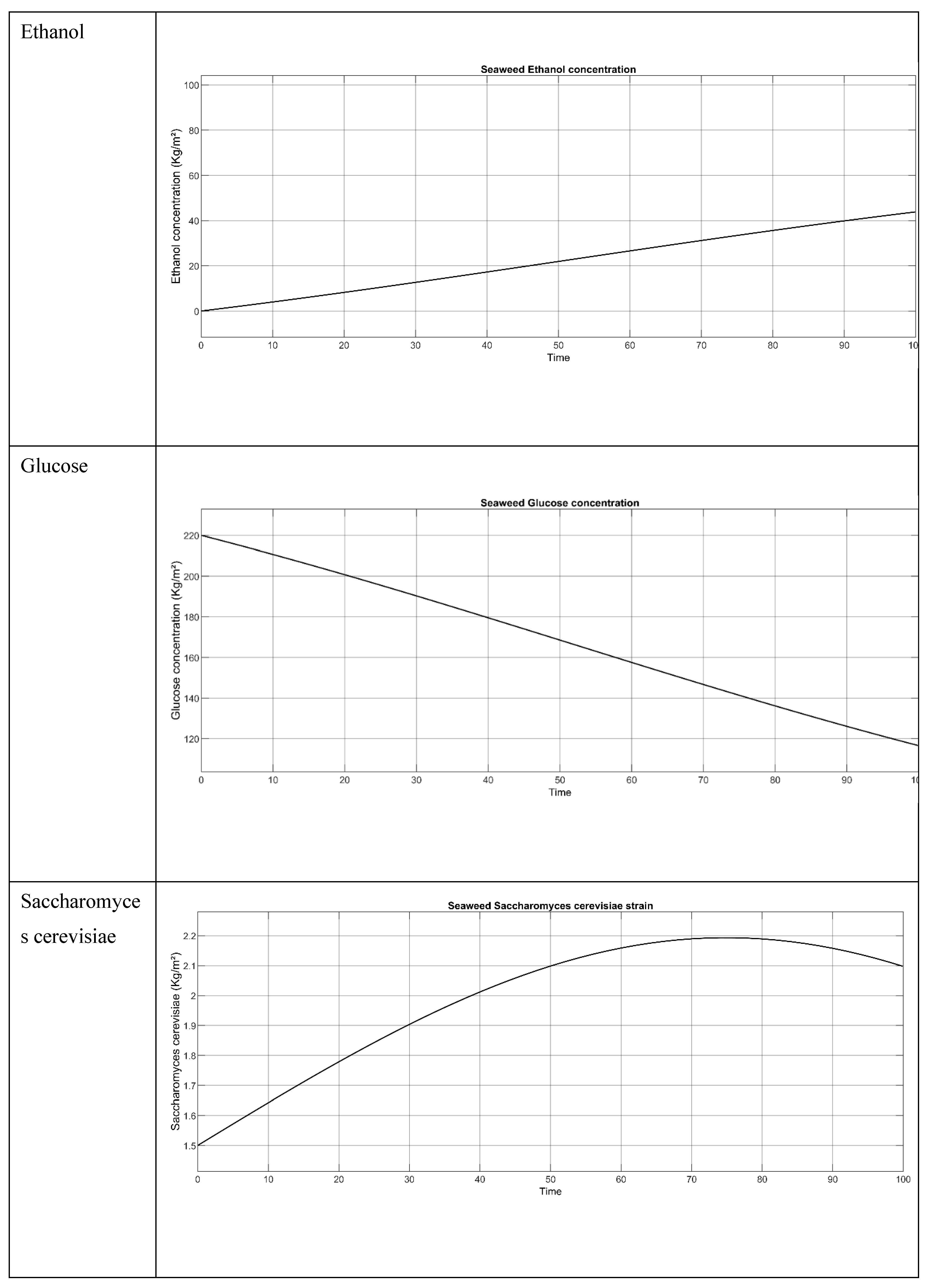

5.2.3. Saccharina latissima (Sugar Kelp)

Figure 6.

Saccharina latissima (Sugar Kelp, Dried) simulation model when temperature is 10 °C.

Figure 6.

Saccharina latissima (Sugar Kelp, Dried) simulation model when temperature is 10 °C.

Figure 7.

Result of the Saccharina latissima (Sugar Kelp, Dried)when all the 3 parameters concentration (S. cerevisiae, Glucose and Ethanol) are employed.

Figure 7.

Result of the Saccharina latissima (Sugar Kelp, Dried)when all the 3 parameters concentration (S. cerevisiae, Glucose and Ethanol) are employed.

Scope

With an important emphasis on their potential as sustainable energy sources, this review concentrates on the synthesis of bioethanol from three different and renewable feedstocks marine algae, lignocellulosic biomass, and vegetable waste. It addresses the chemical composition and availability of these feedstocks and its secondary substrates underlining their metabolic complexity and the importance of efficient pre-treatment procedures, such as physical, chemical, and biological approaches, for improving fermentable sugar release. In order to boost the yield of bioethanol, different fermentation techniques incorporating microbial strains, enzymatic hydrolysis, and bioprocess optimizations are considered. Kinetic modelling is incorporated into the above examination for the purpose of comprehending and enhance the conversion processes. A predictive framework for the production of bioethanol is provided by models like the Michaelis-Menten (MM) Model, Semi-Mechanistic Model, Pseudo-First Order Model, Model Development for Delignification, and Langmuir Adsorption Model, which are examined in connection with enzymatic hydrolysis, microbial fermentation, and biomass processing. The viability of large-scale implementation is also evaluated by examining economic and environmental aspects in conjunction with variables that affect process efficiency, such as reactor designs, substrate concentration, and temperature.

Conclusion

Overall, this study shows how much potential there is to produce bioethanol sustainably using a variety of waste materials, such as marine algae, lignocellulosic biomass, and vegetable scraps. The study used an easy-to-follow and reliable method to successfully turn easily available vegetable waste and leftovers into bioethanol. This approach could help with the energy, financial, and environmental issues associated with traditional fuel sources. The difficulties with lignocellulosic biomass are in effectively dissolving the material's intricate structure to liberate fermentable sugars. However, to maximize sugar output during the conversion process, it is necessary to optimize certain parameters, such as hydrolysis conditions, for marine algal waste to show promise as a feedstock. The application of a genetically altered E. coli strain for bioethanol fermentation was also investigated in this work. Benefits of this strain include a greater spectrum of sugars that it can ferment and a certain amount of resistance to inhibitors of fermentation. Before there is widespread industrial use, there are still challenges to be addressed, like lowering the cost of the enzymes, enhancing the strain's ability to withstand ethanol, and improving the fermentation medium's effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Biotechnology department, PES University.

References

- Shukla-Pandya, Hiral. "Bioenergy as a global public tool and technology transfer." Microbial Biotechnology for Bioenergy. Elsevier, 2024. 263-275. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, Mark. "Examining the Impact of Financial Resources on Solid Waste Management Practices: A Cross-Country Analysis." The National High School Journal of Science Report (2023).

- Ebrahimian, Farinaz, et al. "Effect of pressure on biomethanation process and spatial stratification of microbial communities in trickle bed reactors under decreasing gas retention time." Bioresource technology 361 (2022): 127701. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Ryan A., Omar A. Al-Bar, and Youssri M. Ahmed Soliman. "Biochemical studies on the production of biofuel (bioethanol) from potato peels wastes by Saccharomyces cerevisiae: effects of fermentation periods and nitrogen source concentration." Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 30.3 (2016): 497-505. [CrossRef]

- Sujeeta, Kamla Malik, Shikha Mehta, and Khushboo Sihag. "Optimization of conditions for bioethanol production from potato peel waste." International Journal Chemical Studies 6.1 (2018): 2021-2024.

- Husin, Maryam. Study of Leucaena Leucocephala Seed Biomass as a New Source for Cellulose. Diss. University of Malaya (Malaysia), 2019.

- Khoshkho, Saeedeh Movaghar, et al. "Production of bioethanol from carrot pulp in the presence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and beet molasses inoculum; a biomass based investigation." Chemosphere 286 (2022): 131688. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Chi-Yang, Bo-Hong Jiang, and Kow-Jen Duan. "Production of bioethanol from carrot pomace using the thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus." Energies 6.3 (2013): 1794-1801. [CrossRef]

- Nawirska, Agnieszka, and Monika Kwaśniewska. "Dietary fibre fractions from fruit and vegetable processing waste." Food chemistry 91.2 (2005): 221-225. [CrossRef]

- Miriana, Durante, et al. "Possible Use of the Carbohydrates Present in Tomato Pomace and in Byproducts of the Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Lycopene Extraction Process as Biomass for Bioethanol Production." (2013).

- Osei, Janet Appiah. "Feasibility of Bioethanol Production from Rotten Tomatoes (Solanum Lycopersicum) Using Saccharomyces Cerevisiae." Waste Technology 8.2: 34-38.

- Lenucci, Marcello S., et al. "Possible use of the carbohydrates present in tomato pomace and in byproducts of the supercritical carbon dioxide lycopene extraction process as biomass for bioethanol production." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 61.15 (2013): 3683-3692. [CrossRef]

- Kehili, Mouna, et al. "Supercritical CO2 extraction and antioxidant activity of lycopene and β-carotene-enriched oleoresin from tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) peels by-product of a Tunisian industry." Food and bioproducts processing 102 (2017): 340-349. [CrossRef]

- Roukas, Triantafyllos, and Parthena Kotzekidou. "From food industry wastes to second generation bioethanol: a review." Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 21.1 (2022): 299-329. [CrossRef]

- Demiray, Ekin, et al. "Sequential Anthocyanin Extraction and Ethanol Production from Eggplant Peel Through Biorefinery Approach." BioEnergy Research 17.1 (2024): 383-391. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Pratima, and Piyush Parkhey. "A two-step process for efficient enzymatic saccharification of rice straw." Bioresource technology 173 (2014): 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Abdul Majeed, Shaista Khaliq, and Rabia Sadiq. "Investigation of waste banana peels and radish leaves for their biofuels potential." Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Ethiopia 29.2 (2015): 239-245. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Ávila, Ronaldo Nunes, and José Ricardo Sodré. "Physical–chemical properties and thermal behavior of fodder radish crude oil and biodiesel." Industrial Crops and Products 38 (2012): 54-57.

- Gutiérrez, Rosa Martha Pérez, and Rosalinda Lule Perez. "Raphanus sativus (Radish): their chemistry and biology." The scientific world journal 4 (2004): 811. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Neha, et al., eds. Biofuel production technologies: critical analysis for sustainability. Singapore: Springer, 2020.

- Kalaiarasan, A., and S. Ahmed John. "IJMBR International Journal of Medicobiological Research." Int J Med Res 1.2 (2010): 94-98.

- Khan, Abdul Majeed, et al. "Generation of bioenergy by the aerobic fermentation of domestic wastewater." J. Chem. Soc. Pak 32.2 (2010): 209-214.

- Genemo, Temam Gemeda, Desta Lamore Erebo, and Aschalew Kasu Gabre. "Optimizing bio-ethanol production from cabbage and onion peels waste using yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as fermenting agent." (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gunaseelan, V. Nallathambi. "Biochemical methane potential of fruits and vegetable solid waste feedstocks." Biomass and bioenergy 26.4 (2004): 389-399. [CrossRef]

- Amadi, B. A., E. N. Agomuo, and C. O. Ibegbulem. "Research methods in Biochemistry." Supreme 31 (2004): 50-59.

- Chouaibi, Moncef, et al. "Production of bioethanol from pumpkin peel wastes: Comparison between response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial neural networks (ANN)." Industrial Crops and Products 155 (2020): 112822. [CrossRef]

- Pająk, Paulina, Izabela Przetaczek-Rożnowska, and Lesław Juszczak. "Development and physicochemical, thermal and mechanical properties of edible films based on pumpkin, lentil and quinoa starches." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 138 (2019): 441-449. [CrossRef]

- Vohra, Mustafa, et al. "Bioethanol production: Feedstock and current technologies." Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2.1 (2014): 573-584. [CrossRef]

- Sebayang, A. H., et al. "Optimization of bioethanol production from sorghum grains using artificial neural networks integrated with ant colony." Industrial crops and products 97 (2017): 146-155. [CrossRef]

- Yesmin, M. N., et al. "Bioethanol production from corn, pumpkin and carrot of bangladesh as renewable source using yeast." Acta Chemica Malaysia 4.2 (2020): 45-54. [CrossRef]

- Publicover, Kristen, Tom Caldwell, and Sarah W. Harcum. "Biofuel ethanol production using Saccharomyces bayanus, the champagne yeast." Proceedings of the 32nd Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals. 2010.

- Cheirsilp, Benjamas, and Wageeporn Maneechote. "Zero-Waste Biorefinery." Handbook of Waste Biorefinery: Circular Economy of Renewable Energy. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022. 21-41.

- Saville, B. A., W. M. Griffin, and H. L. MacLean. "Ethanol production technologies in the US: status and future developments." Global bioethanol. Academic Press, 2016. 163-180.

- Lamsal, B. P., H. Wang, and L. A. Johnson. "Effect of corn preparation methods on dry-grind ethanol production by granular starch hydrolysis and partitioning of spent beer solids." Bioresource technology 102.12 (2011): 6680-6686. [CrossRef]

- Sabiha-Hanim, Saleh, and Nurul Asyikin Abd Halim. "Sugarcane bagasse pretreatment methods for ethanol production." Fuel ethanol production from sugarcane (2018): 63-79.

- Mosier, Nathan, et al. "Features of promising technologies for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass." Bioresource technology 96.6 (2005): 673-686. [CrossRef]

- Galbe, Mats, and Guido Zacchi. "Pretreatment: the key to efficient utilization of lignocellulosic materials." Biomass and bioenergy 46 (2012): 70-78. [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, Prakash Kumar, and Sonil Nanda. Bioprocessing of biofuels. CRC Press, 2020.

- Chandel, Anuj Kumar. Biorefinery and Industry 4.0: Empowering Sustainability. Springer Nature, 2024.

- Guedes, A. Catarina, et al. "Algal spent biomass—A pool of applications." Biofuels from algae. Elsevier, 2019. 397-433.

- Avci, Ayse, et al. "Dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of corn stover for enzymatic hydrolysis and efficient ethanol production by recombinant Escherichia coli FBR5 without detoxification." Bioresource technology 142 (2013): 312-319. [CrossRef]

- Cotta, Michael A. "Ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass by recombinant Escherichia coli strain FBR5." Bioengineered 3.4 (2012): 197-202.

- Riansa-Ngawong, Wiboon, and Poonsuk Prasertsan. "Optimization of furfural production from hemicellulose extracted from delignified palm pressed fiber using a two-stage process." Carbohydrate Research 346.1 (2011): 103-110. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Edward W., and Daniel J. Schell. "Conditioning of dilute-acid pretreated corn stover hydrolysate liquors by treatment with lime or ammonium hydroxide to improve conversion of sugars to ethanol." Bioresource technology 102.2 (2011): 1240-1245. [CrossRef]

- Keshwani, Deepak R., et al. "Microwave pretreatment of switchgrass to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis." 2007 ASAE Annual Meeting. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 2007.

- Hu, Zhenhu, Yifen Wang, and Zhiyou Wen. "Alkali (NaOH) pretreatment of switchgrass by radio frequency-based dielectric heating." Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals Held April 29–May 2, 2007, in Denver, Colorado. Humana Press, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Zhenhu, and Zhiyou Wen. "Enhancing enzymatic digestibility of switchgrass by microwave-assisted alkali pretreatment." Biochemical Engineering Journal 38.3 (2008): 369-378. [CrossRef]

- Silva, Neumara Luci Conceição, et al. "Ethanol production from residual wood chips of cellulose industry: acid pretreatment investigation, hemicellulosic hydrolysate fermentation, and remaining solid fraction fermentation by SSF process." Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 163 (2011): 928-936. [CrossRef]

- Pereira Jr, N., M. A. P. G. Couto, and L. M. M. Santa Anna. "Series on biotechnology: biomass of lignocellulosic composition for fuel ethanol production and the context f biorefinery." Amiga Digital UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro 2 (2008): 45.

- Vásquez, Mariana Peñuela, et al. "Enzymatic hydrolysis optimization to ethanol production by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation." Applied Biochemistry and Biotecnology: The Twenty-Eighth Symposium Proceedings of the Twenty-Eight Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals Held April 30–May 3, 2006, in Nashville, Tennessee. Humana Press, 2007.

- Vasić, Katja, Željko Knez, and Maja Leitgeb. "Bioethanol production by enzymatic hydrolysis from different lignocellulosic sources." Molecules 26.3 (2021): 753. [CrossRef]

- Mckiernan, Gerry. "Science. gov." The Charleston Advisor 5.2 (2003): 37-37.

- Keris-Sen, Ulker D., and Mirat D. Gurol. "Using ozone for microalgal cell disruption to improve enzymatic saccharification of cellular carbohydrates." Biomass and bioenergy 105 (2017): 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Shokrkar, Hanieh, Sirous Ebrahimi, and Mehdi Zamani. "Enzymatic hydrolysis of microalgal cellulose for bioethanol production, modeling and sensitivity analysis." Fuel 228 (2018): 30-38. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, Thummala, et al. "Algae: the reservoir of bioethanol." Fermentation 9.8 (2023): 712. [CrossRef]

- Onay, Melih. "Bioethanol production via different saccharification strategies from H. tetrachotoma ME03 grown at various concentrations of municipal wastewater in a flat-photobioreactor." Fuel 239 (2019): 1315-1323. [CrossRef]

- Ngamsirisomsakul, Marika, et al. "Enhanced bio-ethanol production from Chlorella sp. biomass by hydrothermal pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis." Renewable Energy 141 (2019): 482-492. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Vinod, et al. "Production of biodiesel and bioethanol using algal biomass harvested from fresh water river." Renewable Energy 116 (2018): 606-612. [CrossRef]

- Mata, Teresa M., Antonio A. Martins, and Nidia S. Caetano. "Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: a review." Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 14.1 (2010): 217-232. [CrossRef]

- Pendse, Dhanashri S., Minal Deshmukh, and Ashwini Pande. "Different pre-treatments and kinetic models for bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass: A review." Heliyon (2023). [CrossRef]

- Akter, Alima, et al. "Seaweed polysaccharides: Sources, structure and biomedical applications with special emphasis on antiviral potentials." Future Foods (2024): 100440. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Ajar Nath, et al., eds. Biofuels production-sustainability and advances in microbial bioresources. Cham: Springer, 2020.

- Brown, Connor, et al. "Approaching the conformal limit of quark matter with different chemical potentials." arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01032 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sehar, Ujala. Investigating Enzymatic Activity Towards Alpha and Beta Glycosidic Linkages by the Unicellular Extremophilic Red Alga Galdieria sulphuraria. Diss. New Mexico State University, 2022.

- Jutakridsada, Pasakorn, et al. "Bioconversion of saccharum officinarum leaves for ethanol production using separate hydrolysis and fermentation processes." Waste and Biomass Valorization 10 (2019): 817-825. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).