1. Introduction

Battery management systems (BMS) rely on continuous sensing of voltage, current, and temperature (V–I–T) to monitor performance, ensure operational safety, and identify the onset of degradation. As lithium-ion cells age, their measurable signals evolve in characteristic ways–such as prolonged charge time, shortened discharge time, temperature rise under load, or changes in voltage–time plateaus. Extracting actionable health information from these routinely available measurements remains a central challenge for battery diagnostics, especially in the context of edge devices and embedded BMS controllers.

In this work, the term smart sensing refers to the computational intelligence applied at, or near, the sensing layer: namely, using probabilistic models to transform standard BMS telemetry into interpretable indicators of battery health. Rather than proposing new sensor hardware, we focus on data-driven sensing intelligence–that is, algorithms that endow existing V–I–T measurements with the capability to communicate risk, uncertainty, and degradation trends. This interpretation aligns with current directions in intelligent BMS design, where lightweight statistical models operate close to the sensor level to support predictive maintenance and safe operation.

Recent developments in data-driven and model-based diagnostics highlight the need for interpretable, uncertainty-aware estimates of degradation onset. Machine-learning models can deliver accurate predictions but often lack transparency, making them difficult to deploy in safety-critical systems. Deterministic breakpoint heuristics, widely used in practice, provide point estimates but no quantification of uncertainty or confidence in the inferred change. Bayesian changepoint methods offer a principled alternative by explicitly modelling the probability of degradation onset, returning credible intervals and posterior distributions that can be integrated into risk-aware decision policies.

This paper presents a Bayesian single-changepoint formulation tailored for cycle-level indicators derived from V–I–T data. By modelling the trajectory of a simple, physically interpretable health indicator–the ratio of charging time to discharging time at each cycle–we identify the transition from gradual to accelerated degradation and quantify uncertainty in the onset time.

Using a public lithium-ion cell dataset, we illustrate how calibrated posterior estimates of degradation onset can be obtained without access to raw voltage or current waveforms. The proposed formulation does not aim to replace full electrochemical or system-level models; rather, it complements existing BMS telemetry by providing a transparent and computationally efficient method for extracting degradation information from routine measurements. The results and discussion emphasize methodological clarity, deployment-compatibility, and the practical role of Bayesian inference in enabling smart sensing in next-generation BMS. In what follows, we focus on a simple cycle-level health indicator derived from BMS-friendly measurements: the ratio of charging time to discharging time at each cycle. This ratio is directly computed from voltage–time and current profiles and serves as the observable whose degradation trajectory is analysed by the Bayesian changepoint model.

2. Energy Storage Technologies

Energy storage technologies provide the broader operational context in which lithium-ion batteries (Li-ion) have become essential for grid applications, transportation, and renewable integration. Although a wide range of storage principles exists, from electrochemical cells to mechanical and thermal systems, their suitability for high-frequency monitoring and data-driven degradation analysis varies considerably [

1,

2].

Electrochemical, mechanical, and thermal storage systems differ markedly in energy density, round-trip efficiency, power capability, and lifetime. Only a brief overview is therefore provided here to situate Li-ion batteries within this technological landscape. Mechanical and thermal systems offer attractive scaling properties but generally lack the high-resolution telemetry required for condition monitoring. Electrochemical variants, including lead–acid, sodium–sulfur, and various metal–air chemistries, provide established alternatives with diverse cost and performance characteristics [

3,

4].

Among these families, Li-ion batteries have emerged as the dominant choice owing to their high gravimetric and volumetric energy density, favourable cycle life, and rapidly decreasing cost trajectory. Their wide deployment in electric vehicles and stationary BESS installations further benefits from mature manufacturing and well-developed BMS architectures. Importantly, Li-ion systems are instrumented with routinely available voltage, current, and temperature (V–I–T) measurements, enabling the extraction of health-relevant signals for intelligent degradation monitoring [

5]. This level of observability distinguishes Li-ion from most alternative technologies and underpins the modelling approach adopted in this work.

In line with their purely contextual role in this study, the numerical ranges reported in the tables are not intended for design or procurement decisions, but only to indicate broad trade-offs between chemistries.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 summarise representative characteristics of selected electrochemical storage technologies. These values synthesise ranges reported in established surveys [

1,

2,

3] and are intended to provide order-of-magnitude comparisons rather than precise procurement estimates. Reported costs, efficiencies, and cycle lifetimes vary substantially across sources and years, reflecting rapid market evolution and heterogeneous reporting standards. Accordingly, the tabled values should be interpreted as indicative context for technology selection rather than definitive benchmarks.

While non-Li-ion technologies remain important in specialised applications–such as long-duration storage, temperature-resilient designs, or environmentally constrained deployments–they do not typically generate the type of high-resolution telemetry required for statistical degradation detection. In contrast, Li-ion BESS benefit from integrated sensing and monitoring capabilities that support the development of lightweight models deployable within existing BMS infrastructure. For these reasons, the remainder of this manuscript focuses exclusively on Li-ion systems and on extracting interpretable degradation indicators from routine V–I–T measurements to support smart, risk-aware decision-making.

3. Literature Review

Smart sensing for lithium-ion batteries combines advances in sensing hardware, BMS architectures, and data-driven diagnostics. Recent reviews emphasise multi-physical sensing technologies, including mechanical, thermal, and electrochemical modalities, as a route towards more informative battery monitoring [

1,

5,

6]. These works survey a broad landscape of sensing options and integration strategies, but they largely focus on sensor taxonomies and hardware capabilities rather than on simple, BMS-compatible health indicators and probabilistic models for detecting the onset of accelerated degradation from cycle-level data.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and fibre-optic or embedded sensing constitute important strands of smart lithium-ion sensing research. Nováková et al. and Bakenhaster et al. critically review EIS-based diagnostics and their limitations in practical battery applications [

7,

8], while Liu et al. and Jeong et al. discuss advanced optical fibre sensors for thermal and mechanical monitoring in cells and packs [

9,

10]. Xiao et al. and Bao et al. provide complementary surveys of internal temperature estimation and temperature-prediction methods for traction batteries [

11,

12]. Together with the perspective on edge–cloud intelligent BMS architectures in [

13], these contributions make a strong case for richer sensing at the cell and pack level. However, they typically focus on sensing modalities, sensor placement, and hardware constraints; they say relatively little about Bayesian changepoint detection applied to simple cycle-level features derived from standard BMS V–I–T logs. Within the modelling literature, a first group of contributions uses statistical and Bayesian inference for state-of-health (SoH) and remaining useful life (RUL) estimation. Qin et al. propose computationally efficient SoH estimation and transferable RUL prediction schemes that operate on features extracted from voltage and current measurements [

14,

15]. These methods are explicitly designed to be practical and data-efficient, and Rahmanian et al. extend this line of work towards chemistry-agnostic and explainable battery lifetime prediction [

16]. Other studies develop regression- and physics-informed models to represent internal resistance evolution and degradation trends [

17,

18,

19]. While these approaches provide valuable tools for global lifetime prediction and parameter tracking, they typically focus on aggregate lifetime metrics or continuous degradation trajectories. They rarely target the specific question addressed here: the localisation of a single onset point at which degradation accelerates, together with a calibrated posterior distribution over that onset time, using only cycle-level indicators that are directly compatible with production BMS logs.

A second group of contributions uses machine-learning and hybrid approaches for data-driven diagnostics. Yu et al. explicitly design a health indicator for online lifetime estimation in electric vehicle batteries, demonstrating that carefully constructed indicators can substantially improve prediction quality [

20]. Yi et al. employ a digital-twin/LSTM architecture that couples real-time temperature prediction with degradation analysis [

21], and Venugopal et al. benchmark multiple machine-learning models for battery life estimation, illustrating the sensitivity of performance to model class and feature engineering [

22]. Other works explore incremental voltage-difference features [

23], voltage-difference-based multi-fault diagnosis [

24], and pack-level connection fault diagnosis using mechanical vibration signals and belief networks [

25]. These studies collectively confirm that machine-learning can effectively exploit complex nonlinear relationships in battery data. However, most of these models are either black-box or only partially interpretable, and they rarely provide calibrated uncertainty on questions such as “when did accelerated degradation begin?” or “how confident is the model in this onset estimate?”. This absence of explicit posterior onset distributions limits their direct use in safety-critical BMS decision logic.

A third line of work, reviewed for example in [

26], focuses on transfer learning and domain adaptation for SoC/SoH estimation, which is highly relevant for cross-platform or cross-chemistry deployment. While these methods improve robustness and reusability of predictive models, they still generally treat degradation as a continuous quantity or a lifetime horizon to be predicted, rather than as a change in regime where accelerated degradation starts. In parallel, standards and regulatory perspectives emphasise that BMS decisions must be grounded in reliable, auditable indicators and thresholds [

27,

28]. The emerging consensus is that uncertainty quantification is not optional: to support derating strategies, early-warning alerts, and fail-safe operation, BMS must have access to uncertainty-aware degradation metrics that can be mapped to practical safety trip points.

Against this backdrop,

Table 5 summarises representative recent studies in statistical/Bayesian SoH and RUL modelling and in machine-learning-based diagnostics using V–I–T-derived features. Most of the listed works either assume access to rich laboratory instrumentation (in their original experiments) or employ complex models that are challenging to deploy in embedded controllers. By contrast, the present study deliberately targets a narrower but practically important problem: detecting a single changepoint in a simple, physically interpretable health indicator derived from BMS-friendly V–I–T features, and quantifying the uncertainty of that onset. Our Bayesian single-changepoint formulation is intentionally minimalist: it uses only cycle-level summary statistics already recorded in many BMS, and returns posterior distributions for onset time and slope change that can be passed directly to smart-sensing or BMS safety layers. In this sense, the proposed approach complements the existing literature by providing an uncertainty-aware degradation-onset detector that sits between rich multi-sensor hardware studies and high-capacity black-box predictors.

4. Materials

We evaluate the proposed Bayesian changepoint model using the open

Battery Remaining Useful Life (RUL) dataset curated by I. Viñuales and hosted on Kaggle [

31]. The dataset provides

cycle-level measurements for commercial 18650 lithium-ion cells subjected to repeated charge–discharge cycling under controlled laboratory conditions. Each row corresponds to a single cycle and contains summary quantities derived from the voltage and current profiles, including discharge time, charge time, time spent at selected voltage plateaus, and minimum/maximum voltages. No raw waveforms are available, and the analysis therefore focuses exclusively on these aggregated features.

Dataset Provenance

Secondary sources attribute the cells to blended NMC–LCO chemistry of nominal capacity 2.8 Ah, cycled at 25 °C using CC–CV charge (C/2) and discharge (1.5 C). Because the Kaggle export is a combined summary table, cell identifiers are not fully recoverable, but the dataset contains 14 distinct battery trajectories. We treat the provided table as the dataset of record and analyse only the available cycle-level features.

Exploratory Data Characteristics

Before constructing the health indicator used in the changepoint model, we examine raw trends in charge–discharge behaviour. These exploratory plots characterise the usable range of the measurements, reveal data boundaries (such as imposed cycle limits), and motivate the selection of time-based indicators.

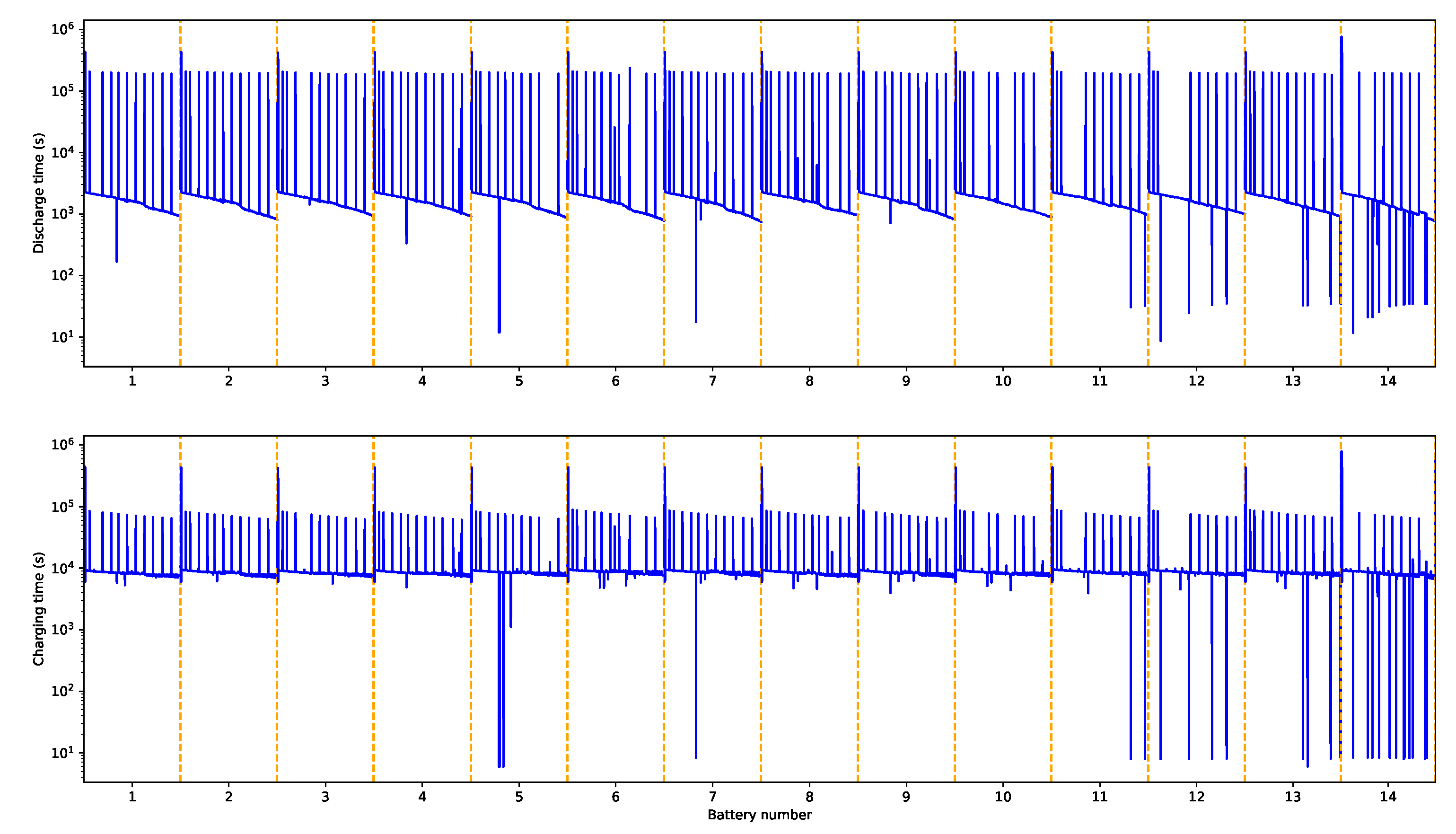

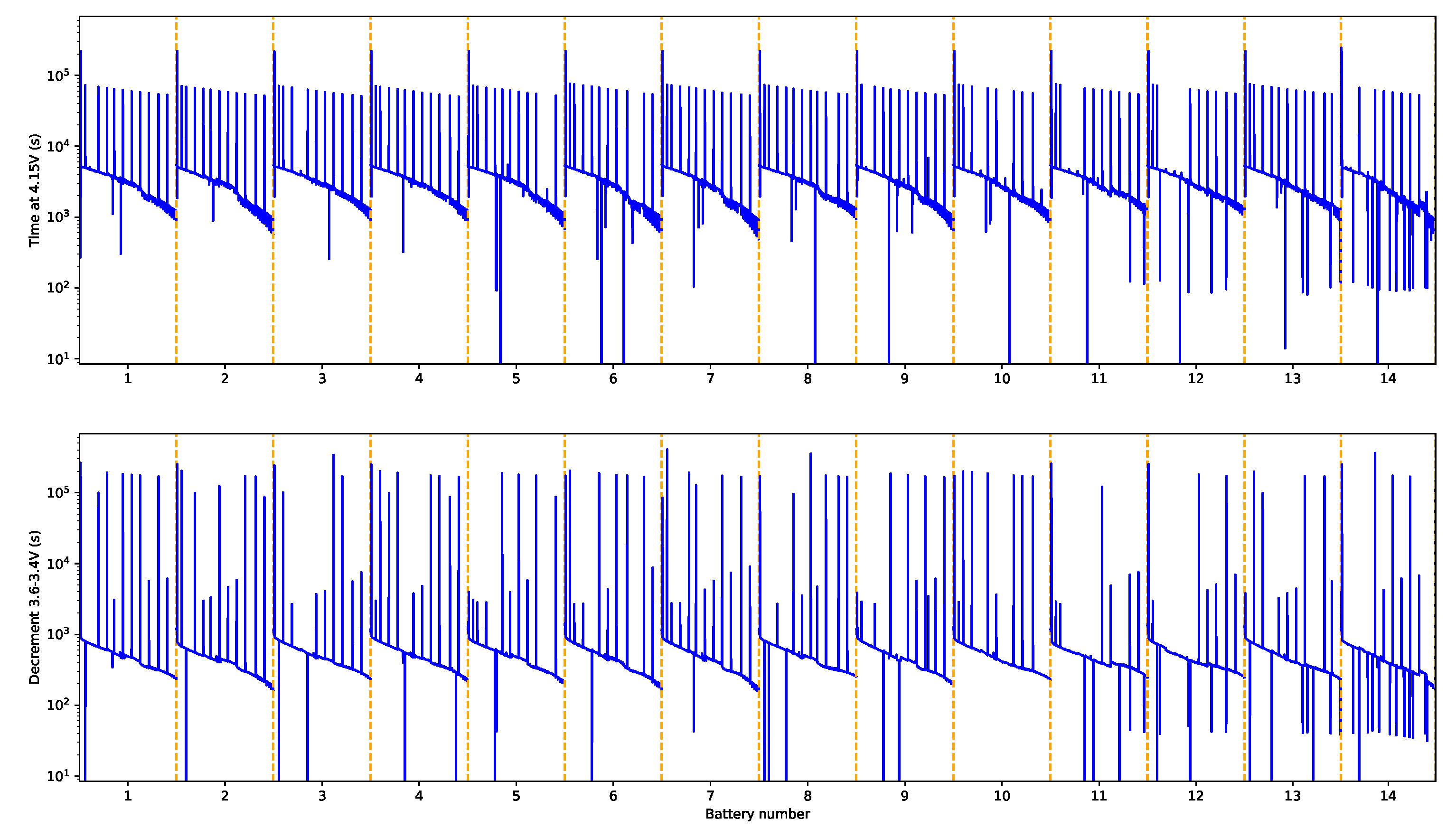

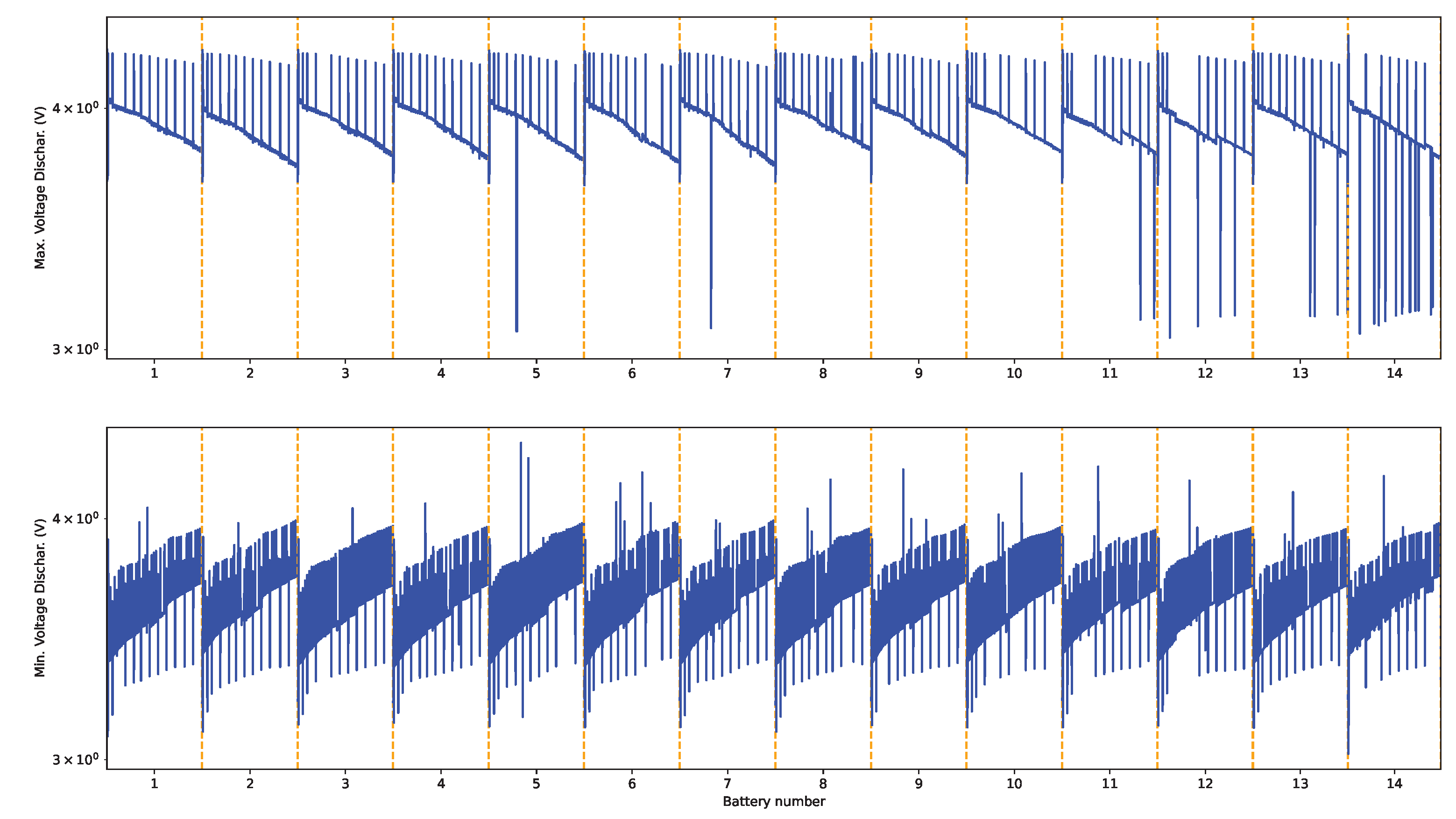

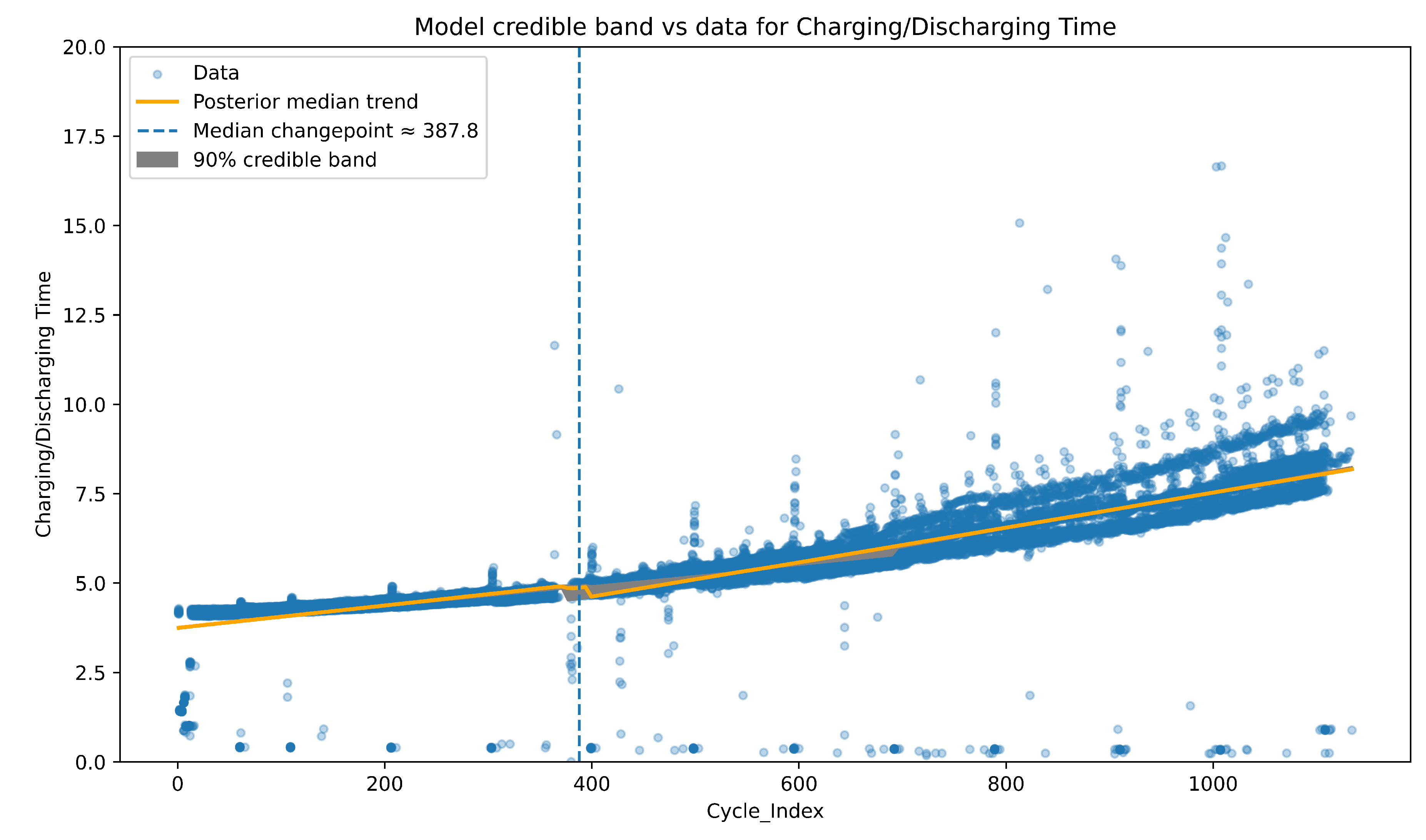

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 summarise the raw discharge time, charge time, time-at-voltage features, and minimum/maximum voltages for all batteries. The vertical orange lines correspond to the cycle limit beyond which some batteries no longer report measurements.

Health Indicator (HI) Definition

Based on the exploratory analysis, we define the primary health indicator (HI) as the ratio:

computed per cycle

i. This ratio captures how the relative duration of charge versus discharge evolves as degradation progresses. Batteries typically exhibit increasing charge time and decreasing discharge time as internal resistance rises and capacity fades; the HI therefore provides a monotonic, interpretable proxy for degradation that is directly compatible with BMS telemetry.

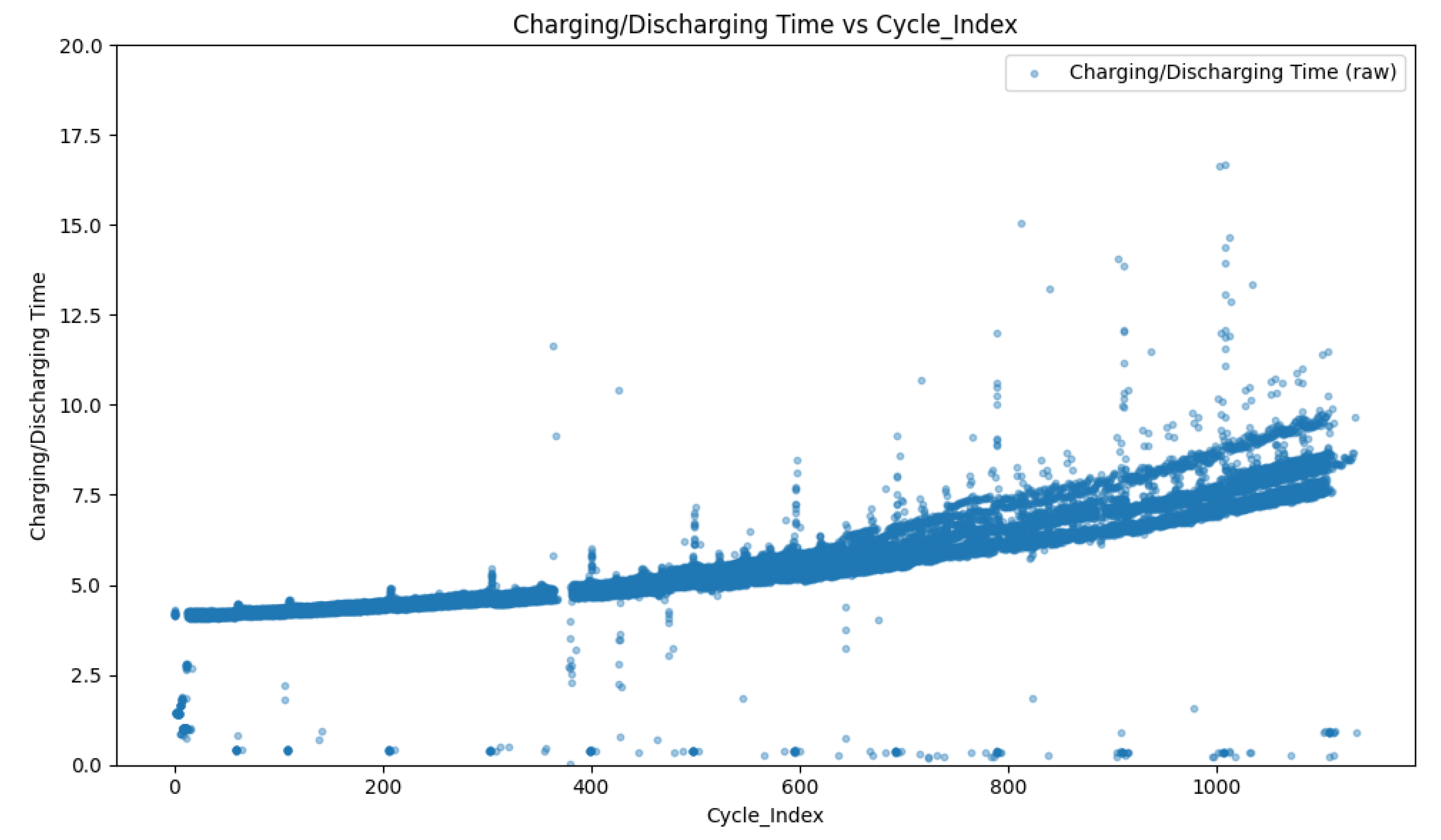

Across all 14 batteries, the HI displays a consistent pattern: a relatively stable early-life region followed by a pronounced change in trend around mid-life.

Figure 4 shows this characteristic trajectory, with a visible shift near approximately 400 cycles. This empirical pattern motivates the use of a single-changepoint Bayesian model.

Preprocessing

To ensure physically meaningful inputs, we apply minimal preprocessing:

remove duplicate rows and cycles with missing values;

enforce physically reasonable limits (voltages in 2.5–4.25 V, times s);

discard entries beyond battery-specific measurement limits;

compute the HI for each cycle;

normalize cycle index for numerical stability in the Bayesian model.

These steps preserve the structure of the dataset while ensuring that the modelling operates on consistent, validated signals directly derived from the raw cycle-level measurements.

5. Methods: Bayesian Changepoint Model for Degradation Detection

This section describes the statistical formulation used to estimate the onset of accelerated degradation from the cycle-level health indicator (HI):

computed for each cycle

i. This ratio is directly available from cycle-level BMS-style measurements and requires no access to raw voltage–current waveforms.

5.1. Preprocessing and Notation

Let

denote the cycle index and

the corresponding health indicator. For numerical stability, the cycle index is standardized:

with

and

the empirical mean and standard deviation. Because the HI often exhibits multiplicative variation, we model the transformed quantity

No smoothing or temporal aggregation is applied; the Bayesian model operates directly on cycle-level values.

5.2. Model Formulation

We assume that the transformed indicator follows a piecewise-linear trend with a single changepoint expressed in the standardized cycle domain. The likelihood is

The parameters and describe the linear trends before and after the changepoint , while represents residual variability. The formulation imposes no assumption that the slopes be increasing or decreasing; inference is fully data-driven.

5.3. Prior Specification

Weakly informative priors regularize the model while permitting broad behaviour:

where

and

are the empirical mean and standard deviation of the log-transformed HI. These priors provide broad support for a wide range of pre- and post-change behaviours without imposing strong structural constraints.

5.4. Posterior Inference

Posterior inference is performed via Hamiltonian Monte Carlo using the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) implemented in PyMC (v5). Four chains are run with 2 000 tuning and 2 000 sampling iterations per chain, yielding 8 000 post-tuning draws. Convergence diagnostics include trace inspection and the statistic.

For interpretability, the posterior for the changepoint is transformed back to the original cycle domain via

5.5. Posterior Predictive Checks

Posterior predictive checks (PPCs) were used to assess whether the Bayesian changepoint model provides a reasonable generative description of the observed health indicator. Replicated datasets were drawn from the posterior and compared to the empirical HI trajectory. The checks confirmed that the simulated trajectories follow the overall trend and variability of the data, indicating that the piecewise-linear formulation with a single changepoint captures the essential structure of the degradation signal. Since these checks serve as internal model diagnostics rather than empirical results, only the methodology is described here, and no PPC figure is included.

5.6. Sampler Diagnostics

Table 6 reports the Monte Carlo standard errors, effective sample sizes, and

values for the parameters. These diagnostics quantify sampling efficiency and are included here as part of methodological transparency. No interpretive conclusions regarding degradation behaviour are drawn from these values in the Methods section.

All inferential and interpretive statements regarding the change in degradation behaviour, slope differences, and the localization of the changepoint are deferred to

Section 6.

6. Results

This section presents the empirical behaviour of the health indicator (HI), the changepoint estimates obtained from the Bayesian model, and posterior predictive assessments of model fit. Throughout, the HI is defined as the per-cycle ratio of charging time to discharging time,

computed directly from the cycle-level features of the Battery Remaining Useful Life (RUL) dataset.

6.1. Behaviour of the Health Indicator over Life

Figure 4 shows the HI trajectory as a function of cycle index for all 14 batteries. At early life, the HI is relatively stable, with modest variation between cycles and between cells. As cycling proceeds, a gradual upward drift appears, followed by a more pronounced increase in the mid-life region. For all analysed batteries, a visible change in trend emerges around approximately 400 cycles, after which the ratio grows more steeply. This pattern is consistent with increasing charge time and decreasing discharge time as internal resistance rises and usable capacity fades.

This qualitative consistency across cells supports the modelling assumption of a single changepoint: before the onset, the HI evolves slowly and approximately linearly; after the onset, the trajectory steepens, reflecting accelerated degradation.

6.2. Estimated Changepoint and Degradation Regimes

The Bayesian changepoint model described in

Section 5 was applied to the log-transformed HI as a function of standardised cycle index. For each battery, the posterior distribution of the changepoint location

(transformed back to the original cycle index

) is unimodal and concentrated in the mid-life region highlighted in

Figure 4. While the exact numerical values differ between cells, all posteriors place the onset of accelerated degradation within the central portion of the monitored life.

Posterior summaries for the pre- and post-change slopes indicate that the post-change trend is more strongly increasing than the pre-change trend. Once the changepoint is reached, the HI grows faster with cycle number, reflecting lengthening charge durations and shortening discharge durations. This aligns with electrochemical expectations for mid-life degradation processes.

Figure 5 illustrates a representative fitted trajectory together with its credible band and the inferred changepoint. The pre-change segment captures the mild drift observed early in life, whereas the post-change segment closely follows the steeper increase at later cycles. Uncertainty is smallest in regions with dense observations and increases near the boundaries of the recorded life.

6.3. Model Fit and Uncertainty Quantification

To evaluate the adequacy of the fitted model, we examined posterior predictive samples and compared them with the observed HI values. The model reproduced both the stable early-life region and the subsequent acceleration in the indicator, suggesting that the inferred changepoint and slope parameters reflect genuine structure in the data rather than artefacts of the prior or numerical fitting. These checks support the validity of using the single-changepoint formulation for this dataset, though they do not constitute external validation.

No systematic misfit patterns (such as sustained bias or curvature inconsistent with the piecewise-linear formulation) are evident. Together with the sampler diagnostics in

Table 6, these PPCs indicate that the model captures the dominant degradation behaviour while maintaining stable posterior inference.

Importantly, the Bayesian formulation produces full posterior distributions for the changepoint and slopes, enabling uncertainty-aware statements such as: “The probability that the post-change slope exceeds the pre-change slope is close to 1”, which are directly useful for risk-aware decision-making in battery management systems.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The results demonstrate that a simple, BMS-compatible health indicator–defined as the ratio of charge time to discharge time–contains sufficient information to identify the transition from gradual to accelerated lithium-ion battery degradation. Across all 14 cells in the dataset, this indicator exhibited a consistent pattern: an early-life region of relative stability followed by a pronounced rise beginning around the mid-life point. The Bayesian changepoint model effectively captured this behaviour, producing posterior distributions for both the timing and magnitude of the transition. The credible intervals around the changepoint estimate provide a calibrated representation of uncertainty, which is critical for applications in battery management systems where safety decisions must be risk-informed rather than based on single point estimates.

Compared with deterministic breakpoint heuristics commonly used in practice, the Bayesian approach offers several advantages. The estimated onset of degradation is probabilistic, allowing BMS implementations to adjust derating curves, safety thresholds, or maintenance recommendations according to confidence levels. The model parameters–including pre- and post-change slopes–remain physically interpretable and do not obscure the underlying behaviour of the indicator. This stands in contrast to high-capacity machine-learning models, which can achieve good predictive performance but rarely provide explicit uncertainty quantification or interpretable explanations for degradation onset.

The framework aligns naturally with modern smart sensing strategies. While the term “smart sensing’’ often refers to enriched sensor hardware, the present work demonstrates that algorithmic intelligence applied at the data-processing layer can also constitute a form of smart sensing. By transforming raw V–I–T measurements–already available in virtually all BMS–into quantitative degradation signals and uncertainty-aware onset estimates, the model enables more informed operational decisions without requiring new transducers or instrumentation. This makes the approach highly compatible with deployment in embedded environments, particularly because the model is low-dimensional and inference can be approximated with lightweight methods suitable for microcontroller-class hardware.

The proposed framework is intentionally minimalist, and this simplicity brings both strengths and limitations. It enhances interpretability and deployability, but it also captures only one axis of degradation–the interplay between charge and discharge time. It cannot disentangle specific degradation mechanisms such as SEI growth, loss of lithium inventory, or impedance-driven ageing. Furthermore, the single changepoint formulation reflects the structure of this particular dataset, whereas real-world degradation can exhibit multiple inflection points or nonlinear transitions. Noise characteristics in operational BMS logs, which may include drift, missing cycles, or inconsistent sampling, may also differ from the curated dataset used here. These factors warrant caution when transferring the model directly to field deployments.

Nonetheless, the approach establishes a foundation for more advanced smart-sensing architectures. The Bayesian framework can be extended to incorporate multiple changepoints, hierarchical structures across cells, or multi-modal indicators when additional sensing data (e.g., internal temperature estimates or low-overhead impedance perturbations) are available. Online inference schemes would enable real-time monitoring and early-warning triggers, while coupling the changepoint outputs with survival or RUL models may further improve predictive maintenance capabilities.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that cycle-level BMS-friendly features, when analysed through a principled Bayesian lens, provide robust and interpretable indicators of the onset of accelerated battery degradation. The proposed method balances transparency, uncertainty quantification, and computational feasibility, making it a strong candidate for integration into next-generation smart BMS systems. By grounding degradation detection in probabilistic reasoning and sensor-level compatibility, the framework contributes to safer, more reliable, and more intelligent battery operation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. J.-K.; Methodology, W. B. and A. J.-K.; Software, W. B.; Validation, A. J.-K.; Formal analysis, W. B.; Investigation, A. J.-K.; Resources, A. J.-K.; Data curation, W. B.; Visualization, A. J.-K.; Writing–original draft, A. J.-K.; Writing–review & editing, J. B., A. J.-K., W. B.; Supervision, J. B.; Project administration, J. B.; Funding acquisition, J. B. Overall contribution: A. J.-K. 60%, W. B. 30%, J. B. 10%. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Work of Anna Jarosz and Jerzy Baranowski partially realised in the scope of project titled ”Process Fault Prediction and Detection”. Project was financed by The National Science Centre on the base of decision no. UMO-2021/41/B/ST7/03851. Part of work was funded by AGH’s Research University Excellence Initiative under project “DUDU – Diagnostyka Uszkodzeń i Degradacji Urzadzeń”. Waldemar Bauer’s work was funded by AGH’s Research University Excellence Initiative under project Waldemar Bauer

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is the “Battery Remaining Useful Life (RUL)” dataset curated by I. Viñuales (Kaggle, 2022) [

31]. It is distributed as a single CSV of cycle-level features derived from laboratory aging experiments on commercial 18650 Li-ion cells.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, authors used ChatGPT 5 for the purposes of style verification and refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Šimić, Z.; Knežević, G.; Topić, D.; Pelin, D. Battery energy storage technologies overview. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering Systems 2021, 12, 53–65.

- Vishnumurthy, K.; Girish, K. A comprehensive review of battery technology for E-mobility. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2021, 98, 100173.

- Neburchilov, V.; Zhang, J. Metal-Air and Metal-Sulfur Batteries: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer, 2016; pp. 1–195.

- Pu, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhong, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H. Electrodeposition Technologies for Li-Based Batteries: New Frontiers of Energy Storage. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1903808.

- Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Ma, X.Y.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.G. Advancing Smart Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review on Multi-Physical Sensing Technologies for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2024, 17, 2273. [CrossRef]

- An, C.; et al. Advances in Sensing Technologies for Monitoring States of Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Journal of Power Sources 2025. In press.

- Nováková, K.; Papež, V.; Sadil, J.; Knap, V. Review of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Methods for Lithium-Ion Battery Diagnostics and Their Limitations. Monatshefte für Chemie – Chemical Monthly 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bakenhaster, S.T.; et al. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Battery Research: A Review. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Advanced Functional Optical Fiber Sensors for Smart Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Materials Advances 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.; et al. High-Resolution Thermal Monitoring of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Fiber-Optic Sensors. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2024. Article in press.

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhao, T.; Kuang, Y.; Yin, B.; Yuan, R.; Song, L. Review—Online Monitoring of Internal Temperature in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2023, 170, 050521. [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; et al. Enhancing Lithium-Ion Battery Monitoring: A Critical Review of Temperature Prediction Methods in Electric Vehicles. Batteries 2024, 10, 421. [CrossRef]

- Mulpuri, S.K.; Sah, B.; Kumar, P. An Intelligent Battery Management System (BMS) with End–Edge–Cloud Connectivity – A Perspective. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2025, 9, 1142–1159. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Fan, X.; Fan, Y.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, D. A Computationally Efficient Approach for the State-of-Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2023, 16, 5414.

- Qin, H.; Fan, X.; Fan, Y.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, D. A Transferable Prediction Approach for the Remaining Useful Life of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Small Samples. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2023, 13, 8498.

- Rahmanian, F.; Lee, R.; Linzner, D.; Nuss, L.; Stein, H. Attention towards chemistry agnostic and explainable battery lifetime prediction. npj Computational Materials 2024, 10, 100.

- Xu, R.; Wang, D.; Yan, G.; Li, X.; Li, G. Direct current internal resistance decomposition model for accurate parameters acquisition and application in commercial high voltage LiCoO2 battery. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 70, 108100.

- Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Xue, Z.; Tian, L.; Zheng, X. Weight optimized unscented Kalman filter for degradation trend prediction of lithium-ion battery with error compensation strategy. Energy 2022, 251, 123890.

- Sun, Y.; Tian, H.; Hu, F.; Du, J. Method for Evaluating Degradation of Battery Capacity Based on Partial Charging Segments for Multi-Type Batteries. Batteries 2024, 10, 187.

- Yu, B.; Qiu, H.; Weng, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, H. A health indicator for the online lifetime estimation of an electric vehicle power Li-ion battery. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2020, 11, 1–11.

- Yi, Y.; Xia, C.; Feng, C.; Qian, L.; Chen, S. Digital twin-long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network based real-time temperature prediction and degradation model analysis for lithium-ion battery. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107203.

- Venugopal, P.; Shankar, S.; Jebakumar, C.; Reka, S.; Golshan, M. Analysis of Optimal Machine Learning Approach for Battery Life Estimation of Li-Ion Cell. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 159616–159626.

- Naha, A.; Han, S.; Agarwal, S.; Yoon, J.; Oh, B. An Incremental Voltage Difference Based Technique for Online State of Health Estimation of Li-ion Batteries. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 9526.

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, S.; Yang, Z.; He, Y. A multi-fault diagnosis method for lithium-ion battery pack using curvilinear Manhattan distance evaluation and voltage difference analysis. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 67, 107575.

- Shen, D.; Lyu, C.; Yang, D.; Hinds, G.; Wang, L. Connection fault diagnosis for lithium-ion battery packs in electric vehicles based on mechanical vibration signals and broad belief network. Energy 2023, 274, 127291.

- Shen, L.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Zhu, L.; Shen, H. Transfer Learning-Based State of Charge and State of Health Estimation for Li-Ion Batteries: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2024, 10, 1465–1481.

- IEEE P2686 Working Group. Recommended Practice for Battery Management Systems – Safety and Reliability (Draft Status Update, 2024). IEEE SA ballot approved; slide deck (Sandia National Laboratories) summarizing scope and best practices, 2024.

- Tadoum, D.D.; et al. Standards and Regulations for Battery Management Systems: A Review. Batteries 2025, 11, 716. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Li, Z.; Yang, R.; Ma, S.; Sun, F. Fast self-heating battery with anti-aging awareness for freezing climates application. Applied Energy 2022, 324, 119762.

- Sai, L.; Dai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Bai, Y. Multiple-functional LiTi2(PO4)3 modification improving long-term performances of Li-rich Mn-based cathode material for advanced lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 613, 234870.

- Viñuales, I. Battery Remaining Useful Life (RUL), 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).